Abstract

Purpose: To measure the impact of increasing sterile compounding batch frequency on pharmaceutical waste as it relates to cost and quantity.

Methods: Pharmaceutical IV waste at a tertiary care hospital was observed and recorded for 7 days. The batching frequency of compounded sterile products (CSPs) was then increased from twice daily to 4 times daily. After a washout period, pharmaceutical IV waste was then recorded for another 7 days. The quantity of units wasted and the cost were compared between both phases to determine the impact that batching frequency has on IV waste, specifically among high- and low-cost drugs.

Results: Patient days increased from 2,459 during phase 1 to 2,617 during phase 2. The total number of CSPs wasted decreased from 3.6 to 2.7 doses per 100 patient days. Overall cost was reduced from $4,585.36 in phase 1 to $4,453.88 in phase 2. The value of wasted high-cost drugs per 100 patient days increased from $146 in phase 1 to $149 in phase 2 (p > .05). The value of wasted low cost drugs per 100 patient days decreased from $41 in phase 1 to $21 in phase 2 (p < .05).

Conclusion: Lean batch IV methodology reduced overall waste quantity and cost. The highest impact of the intervention was observed among low-cost CSPs.

Keywords: batch frequency, compounded sterile products, lean batch IV, pharmaceutical cost, pharmaceutical waste, sterile compounding

PROBLEM

Multiple inpatient sterile compounded doses are prepared in “batches” in the majority of hospitals across the United States and the world.1 This is a process in which doses that are due at a given administration timeframe are prepared upfront in central or satellite institutional pharmacies to maximize operational and workflow efficiencies. The preparation of patient-specific sterile compounds is a time-consuming process that requires a great deal of attention to avoid any errors being introduced.1 The “batching” method is a prospective approach, where a hospital pharmacy produces several batches of medications that are tailored to the patients receiving them. There is normally a gap of several hours (or more) between the time of preparation and that of administration. During this gap, several variables can alter the intended use of dispensed medications. For example, doses might be discontinued or modified, patients might be transferred or discharged, or doses might be misplaced in the health care system requiring reproduction. These variables contribute to compounded sterile products (CSPs) being unused and eventually wasted, which costs the health care system unretrievable expenses.2 In many cases, the unused medications cannot be repurposed to other patients due to very specific dosing criteria (eg, weight-based doses) or beyond-use dating (BUD) issues. To minimize waste, an optimal balance between timely sterile compounded preparation (frequency) and personnel workload is necessary. Many studies were conducted of alternatives that might reduce the waste of sterile compounded products and doses.2–5 A review of the current literature3,6–10 suggests that the well-established practice of lean intravenous (IV) methodology had a positive effect on pharmacy efficiency as well as the cost of operations.3 The practice of lean IV preparation methods involves making batches of IV medications more frequently throughout the day, with less medications being prepared in each respective batch. Its aim is to prepare these medications in a more expedient manner while avoiding the introduction of medication errors throughout the process.

Florida Hospital Tampa is a 517-bed facility located in Tampa, Florida. Prior to this study, patient-specific CSPs (mostly IV medications) at this site were prepared daily in 2 large batches. With this batch design and due to a consistent and increasing amount of these doses being wasted, an operational intervention was put in place to improve the pharmacy workflow and finances. The study was to determine the impact of changing patient-specific batch frequency on pharmaceutical sterile compounding waste and expenses. A secondary output of this study was to determine subsets of doses for which such a change might produce the maximum positive effect.

METHOD

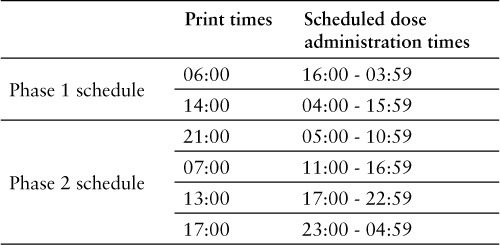

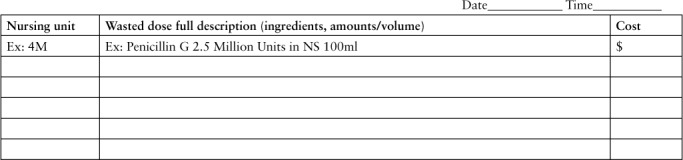

This was a 2-phase, single-arm interventional analysis with a washout period between phases. A 2-sample t test was used to calculate p values. During phase 1, CSPs were prepared daily in 2 batches. The print times of these products and the doses that were covered are outlined in Table 1. Each phase was conducted over 7 days during which we recorded the CSPs that were returned to pharmacy to be wasted. To be included in the study, wasted medications were required to be patient-specific, prepared and delivered from pharmacy using aseptic technique in sterile compounding, and returned to pharmacy within the study timeframe. Excluded were nonsterile or nonliquid doses, either patient-specific or non–patient specific. Throughout the day, pharmacy technicians would make medication deliveries across the hospital to stock automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) with patient-specific or non–patient-specific medications and to retrieve unused or expired ones. These deliveries took place every hour during each day. At each ADC throughout the hospital, the technicians collected any CSPs that had expired or that had exceeded the timeframe during which a patient should have received it. The technicians then returned these doses to pharmacy and wasted the ones that had expired. During this phase, technicians inventoried the patient-specific bins in ADCs and took note of CSPs left in these bins to be administered later in the day. This process of reconciliation aimed at avoiding the preparation of a duplicate of a patient-specific dose if it already existed in the ADC's patient-specific bin. In many occasions these doses might have had delayed administration due to reasons related to the patient course of care, such as the patient leaving the care area within the hospital to undergo a diagnostic procedure in a different department. All returned CSPs to be wasted were placed by technicians in a designated study container throughout the study period where they were then recorded (see Figure 1). Recording was performed by a single person throughout both phases of study. The recorded information was taken from the labels attached to the products including the drug name, strength, dose, and unit location. After all needed information was collected, the designated container of medication waste was emptied and medications wasted according to applicable federal, state, and institutional guidelines. Information was recorded twice a day on each of the study days; once in the morning (08:00) and again in the afternoon (15:00). The pricing information of these CSPs was obtained from the pharmacy purchasing department, and it represented the cost incurred by pharmacy to obtain the medications (non-340b pricing). Total cost of each CSP consisted of the cost of the drug and the cost of the diluent. At the end of the 7 days, the pharmacy implemented the lean IV batch methodology and began producing the CSPs 4 times per day.1 The specific print times and doses covered of each batch are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Compounded sterile products batch frequency schedule

Figure 1.

Intravenous waste study dose log.

During the first 8 days of implementation of this new process, a washout period was put into place to allow sufficient clearance of workflows and returned doses associated with the old batch frequency. During the 8-day washout period, no doses were collected for this study to allow all CSPs produced under the twice-a-day batching frequency to be consumed (or wasted if expired). After the washout period, phase 2 of this study was conducted in a similar fashion and mechanics as phase 1. The study's primary endpoint was to measure the impact of batch frequency changes on quantity and the cost of wasted CSPs. Results were stratified according to CSP's cost, with low-cost CSPs defined as costs equal to or below $100 per dose and high-cost CSPs defined as costs above $100 per dose. A secondary output of this study was to determine subsets of doses for which such a change might produce the maximum positive effect.

RESULTS

Wasted doses were collected from 27 nursing units that were distributed as 13 general practice units, 10 critical care units, 2 pediatric units, and 2 observation units. The nursing unit locations of the wasted CSPs were recorded in both phases for internal process improvement.

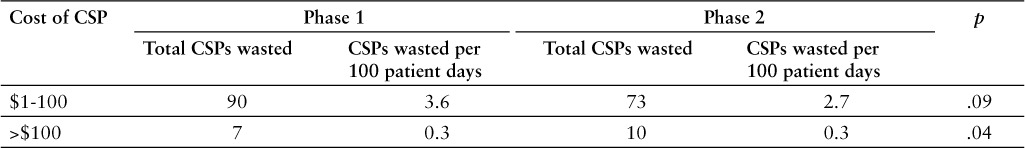

Total wasted CSPs decreased from 97 doses wasted in phase 1 to 83 doses wasted in phase 2. These numbers represent 2.2% and 1.8%, respectively, of total CSPs prepared during each phase. These doses were further stratified into high- and low-cost drugs. The total wasted high-cost CSPs significantly increased from 7 doses in phase 1 to 10 doses in phase 2 (p < .05). The total wasted low-cost CSPs decreased from 90 doses in phase 1 to 73 doses in phase 2 (p > .05). The values of the number of doses wasted were adjusted based on the hospital's number of patient days for phase 1 and phase 2, respectively. Total patient days in phase 1 were 2,459 compared to 2,617 in phase 2. Based on this adjustment, total wasted high-cost CSPs did not change between both phases (0.3 doses per 100 patient days). However, there was a decrease in total number of wasted lowcost CSPs (3.6 to 2.7 doses per 100 patient days). These findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of phase 1 and phase 2 number of wasted compounded sterile products (CSPs)

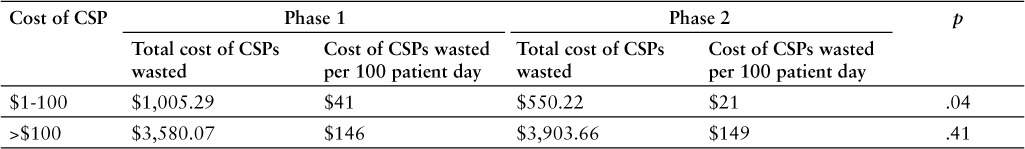

The total cost of CSPs wasted decreased from $4,585.36 in phase 1 to $4,453.88 in phase 2. The total costs of the wasted drugs were once again stratified into high- and low-cost drugs. The value of wasted high-cost drugs increased from $3,580.07 in phase 1 to $3,903.66 in phase 2. The value of wasted low-cost drugs decreased from $1,005.29 in phase 1 to $550.22 in phase 2. The values of the costs of the doses wasted were adjusted based on the hospital's number of patient days for phase 1 and phase 2 (2,459 and 2,617, respectively). Based on this adjustment, total value of wasted high-cost drugs slightly increased from phase 1 to phase 2 ($146 to $149 per 100 patient days; p > .05). The total value of wasted low-cost drugs significantly decreased from phase 1 to phase 2 ($41 to $21 per 100 patient days; p < .05). These findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of phase 1 and phase 2 cost stratification of wasted compounded sterile products (CSPs)

DISCUSSION

The use of lean batch methodology produced results that are consistent with previous literature.3 In terms of low-cost drugs, increasing the IV batch frequency from twice daily to 4 times daily resulted in a savings of $455.07 within a 7-day period (annual savings of $23,663.64). However, there was an increase in the number of high-cost drug doses wasted and the total value of high-cost drugs that were wasted. This might be due in part to the unpredictable nature of when and where these doses were to be dispensed. For example, patients of specific care acuity might require high-cost medications that are not utilized pending the patients' case progress. This would suggest that lean batch methodology would have the greatest impact on low-cost medications. During this study, a significant outlier was identified in high-cost doses wasted in phase 2. A single CSP was wasted at a cost of $1,508. Despite an overall reduction in cost in phase 2, this wasted CSP significantly skewed the results. Therefore, an even larger reduction of cost may have been observed when accounting for this outlier. These findings suggest that batching high-cost CSPs may need to be handled differently than low-cost CSPs in a manner that further controls waste. This may include creating separate, more frequent batches for such compounds and compounding these products as close as practically possible to the time of administration.

Increasing the CSP batch frequency from twice to 4 times daily reduced the dose coverage timeframe from 12 to 6 hours (Table 1). A 12-hour dose coverage timeframe inherently creates a larger window during which uncontrollable factors can be introduced, such as discontinued doses and patient discharge. Doses prepared closer to the time of administration would generally result in less opportunity for these factors to lead to medication waste. This logic was demonstrated in the study results that showed a general reduction of number of wasted CSPs when more frequent batches were implemented. Correlating waste savings with such uncontrollable health system factors resulting in pharmaceutical waste was not possible at the time of study, but it is warranted as an endpoint for future exploration.

Increasing the CSP batch frequency in this study reduced labor requirements in the sterile compounding area and in delivery areas. This was due, in part, to the fact that compounding closer to time of administration reduced the uncontrollable factors contributing to repeated or wasteful compounding/deliveries, such as in the case of discontinued doses or discharged patients. Although not specifically measured in this study, this favorable impact on cost of labor would provide a good target endpoint for future research with a larger scope of study.

There were some limitations impacting this study. During phase 1 of the study, a medication reconciliation process impacted the observed number of doses wasted. This process was not utilized in phase 2 of the study, because it was assumed that this phase would inherently result in less waste as a result of higher batching frequency. If the medication reconciliation process had been performed in phase 2, then it would have been reasonable to expect an even greater reduction of waste. As a result, the reported impact of the lean batch method on CSP waste can be considered a conservative representation. The study methods were conducted between the hours of 0800 and 1500. Outside of this timeframe, such as during overnight shift, study methods were not supervised by a study investigator. However, clear communication was delivered to pharmacy staff to ensure maximum compliance with established study protocols.

The last batch during the day printed at 21:00 (Table 1) to accommodate skeleton staffing during the midnight shifts. This batch had the most lead time prior to dose administration time (05:00 to 10:59). Adjusting the print time to be closer to administration time would be expected to result in further reduction in CSP waste.

The results obtained from this study are representative of a 517-bed tertiary care hospital. Tertiary hospitals generally encompass a broader and more complicated patient mix and care specialties. The outcomes reported in this study may not necessarily apply to primary care facilities or to smaller hospital settings.

CONCLUSION

The issue of institutional sterile compounding waste as it relates to batching frequency was highlighted and investigated in this study. Based on the findings, implementation of a lean batch IV methodology led to an overall reduction in waste quantity and cost. Low-cost CSPs seemed to demonstrate a greater benefit from such a methodology than high-cost CSPs.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. . ASHP statement on unit dose drug distribution. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1975; 32: 835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al-Dhawailie AA. Control of intravenous medication wastage at a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2011; 32: 62– 65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. L'Hommedieu T, Kappeler K.. Lean methodology in I.V. medication processes in a children's hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010; 67: 2115– 2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoolihan RJ, Erickson BA.. Strategies for reducing i.v. drug waste and coping with increased workload. Hosp Pharm. 1987; 22( 9): 871– 876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diehl LD, Goo ED, Sumiye L, Ferrell R.. Reducing waste of intravenous solutions. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992; 49: 106– 108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ryan DM, Daniels CE, Somani SM.. Personnel costs and preparation time in a centralized intravenous admixture program. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1986; 43( 5): 1222– 1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gillerman RG, Browning RA.. Drug use inefficiency: A hidden source of wasted health care dollars. Anesth Analg. 2000; 91( 4): 921– 924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coppola PA, Cassidy AP.. Reducing waste: A significant cost containment measure in an i.v. additive program. Hosp Pharm. 1987; 22( 12): 1215– 1216, 1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Newhouse JG, Paul VM, Waugh NA, Frye CB.. Reducing i.v. waste to under 2.25 percent. Hosp Pharm. 1988; 23( 3): 241– 242, 246– 247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitchell SR. Monitoring waste in an intravenous admixture program. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1987; 44( 1): 106– 111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]