Abstract

Background:

The distal splenorenal shunt is an effective procedure for the treatment of portal hypertension in children. However, there has been no report about laparoscopic distal splenorenal shunt in the treatment of portal hypertension in children.

Methods:

From December 2015 to August 2016, 4 children with upper gastrointestinal bleeding underwent laparoscopic distal splenoadrenal shunt. Portal hypertension and splenomegaly were demonstrated on the preoperative computed tomography (CT) and sonography. The distal splenic vein was mobilized and anastomosed to the left adrenal vein laparoscopically. All patients were followed-up postoperatively.

Results:

The laparoscopic distal splenoadrenal shunt was successfully performed in all patients. The liver fibrosis was diagnosed by postoperative liver pathology. The operative time ranged from 180 to 360 minutes. The blood loss was minimal. The length of hospital stay was 6 to 13 days. The duration of following-up was 1 to 9 months (median: 3 months). The portal pressure and splenic size were decreased postoperatively. The complete blood count normalized and the biochemistry tests were within normal range after surgery. Postoperative ultrasound and CT confirmed shunt patency and satisfactory flow in the splenoadrenal shunt in all patients. No patient developed recurrence of variceal bleeding.

Conclusions:

The laparoscopic splenoadrenal shunt is a feasible treatment of portal hypertension in children.

Keywords: children, laparoscopy, portal hypertension, Warren shunt

1. Introduction

With the improvements of laparoscopic surgery, the laparoscopic techniques were used for the treatment of portal hypertension in children, such as laparoscopic splenectomy with esophagogastric devascularization and laparoscopic splenic vessel ligation.[1–3] However, laparoscopic splenectomy and splenic vessel ligation are only used to treat the hypersplenism caused by portal hypertension, and laparoscopic esophagogastric devascularization is used to control the variceal bleeding. Splenectomy can effectively relieve the hypersplenism, but it is associated with perioperative and postoperative complications.[4] The long-term result of laparoscopic splenic vessel ligation is uncertain. The distal splenorenal shunt (Warren shunt) is an effective procedure for the treatment of portal hypertension in children[5,6]; it preserves the spleen, avoids the overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis, reduces the splenic vein pressure and keeps the hepatopetal blood flow of portal vein. Long-term patency rates greater than 90% have been reported. However, there has been no report about laparoscopic distal splenorenal shunt in the treatment of portal hypertension in children. In this study, we reported our experience in laparoscopic distal splenoadrenal shunt for the treatment of portal hypertension.

2. Patients and methods

Between December 2015 and August 2016, 4 children (age 2.7–7.8 years, 3 boys and 1 girl) with hematemesis and melaena were admitted to our hospital. The abdominal sonography, computed tomography (CT), blood routine, and biochemistry were performed preoperatively. The abdominal ultrasound and CT showed portal hypertension, liver fibrosis, and splenomegaly. The liver function was normal.

Surgical indication included absence of previous surgical history; portal hypertension caused by liver cirrhosis and fibrosis, or extrahepatic portal hypertension which was unsuitable for Rex shunt; the diameter of adrenal vein was greater than 5 mm; no contraindication of laparoscopic surgery.

2.1. Surgical procedure

The patients were placed in supine position. After induction of general anesthesia, a transumbilical 2 to 3 cm superficial longitudinal incision was made. The small intestine was exteriorized through the umbilical incision, and a catheter was inserted into a branch of superior mesenteric vein to measure the portal pressure and perform the mesenteric angiography. The selective mesenteric angiography was used to identify the morphology of portal venous system. A 13-mm port was placed in the umbilical incision and other three 5-mm ports were placed as shown in Fig. 1. The pancreas and splenic hilum were exposed through dissecting the gastrocolic and splenogastric ligament and suspension of posterior gastric wall. The splenic artery was dissected along the upper border of pancreas, and was clipped using a vascular clamp (Fig. 2). The splenic vein was dissected off the posterior and inferior borders of pancreas, and was ligated using a hem-o-lok at the junction of splenic and inferior mesenteric vein (Fig. 3A). The proximal end of splenic vein was clipped using a vascular clamp (Fig. 3B). The left renal and adrenal veins were exposed by dissecting the descending colon which was retracted to the right by the assistant (Fig. 4A). The adrenal vein was clipped at the confluence of adrenal and renal vein (Fig. 4B). The adrenal vein was ligated and divided 1 cm from the renal vein, and the lumen of splenic and adrenal vein was irrigated by heparinized saline through a percutaneous tube to avoid thrombosis (Fig. 5). The adrenal vein was anastomosed end-to-end with the distal end of the splenic vein (Fig. 6). The vascular anastomosis was performed using 7/0 Prolene suture discontinuously. Under laparoscope, the anastomotic stoma was amplified, which helped to expose the vascular end and perform the vascular anastomosis. After anastomosis, the vascular clamps of splenic and renal vein were removed, and the vascular clamp of splenic artery was removed after confirming that there was no anastomotic bleeding. The patency of the bypass vein was checked and the superior mesenteric vein pressure was measured.

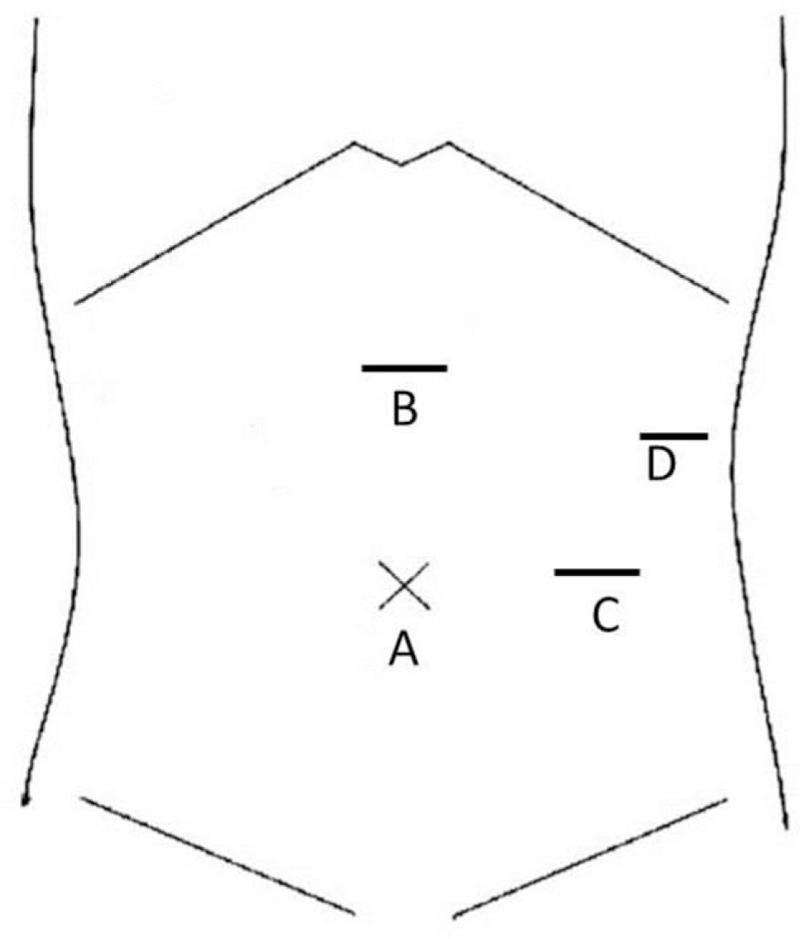

Figure 1.

The position of the trocars. Trocars A and B were used by the surgeon, trocar C was used for the camera, and trocar D was used by the assistant.

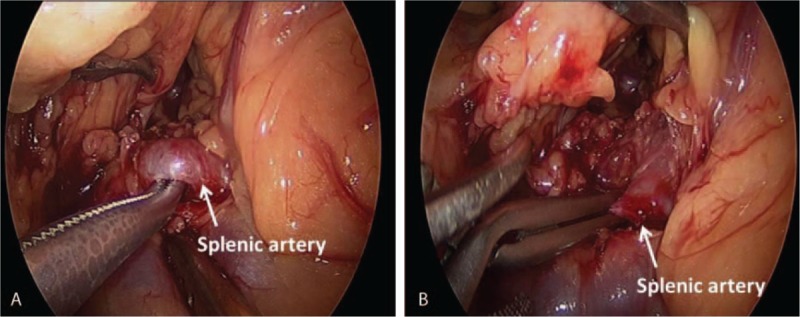

Figure 2.

The splenic artery was dissected (A), and the splenic artery was clipped using a clamp (B).

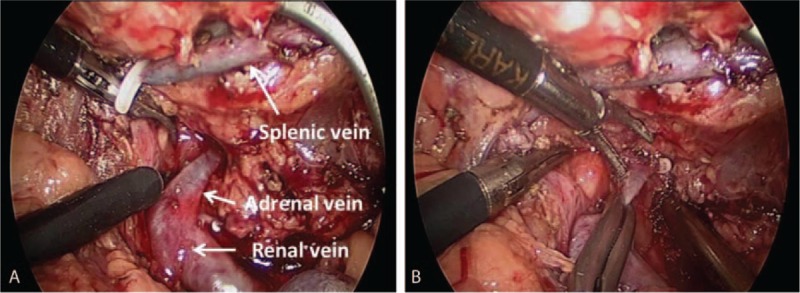

Figure 3.

The distal end of splenic vein was ligated using a hem-o-lok (A); the proximal end of the splenic vein was clipped using a clamp (B).

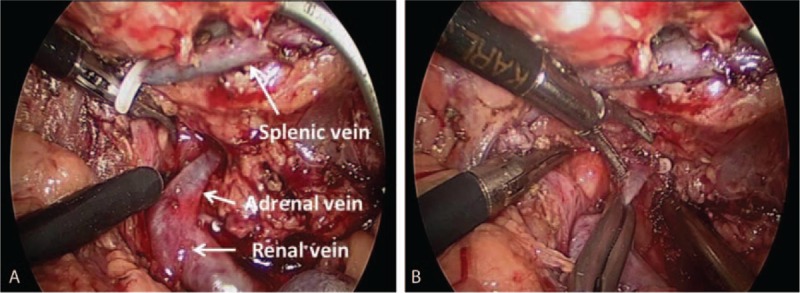

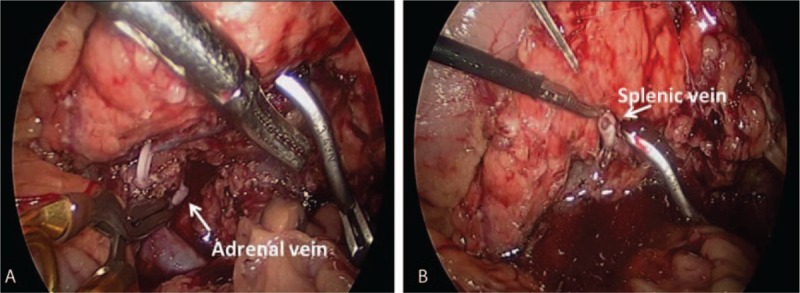

Figure 4.

The dissection of renal and adrenal vein (A), and the adrenal vein was clipped using a clamp (B).

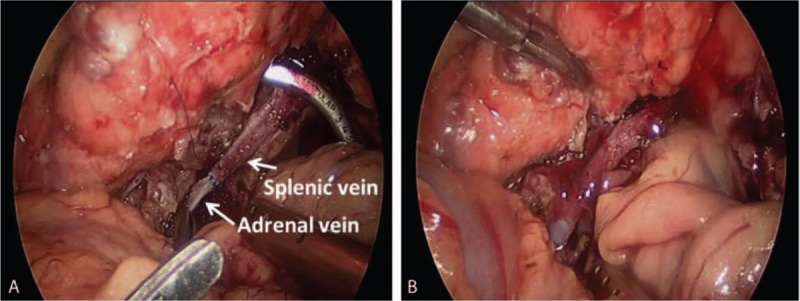

Figure 5.

The adrenal vein was cut off (A), and the lumen of splenic vein was irrigated by heparinized saline (B).

Figure 6.

The distal end of splenic vein was anastomosed with the adrenal vein (A: before surgery; B: after surgery).

All the children were followed up at postoperative 1, 3, 6, 12 months and every 6 months thereafter. During the follow-up, abdominal ultrasound, CT, upper gastrointestinal imaging (UGI), and laboratory tests (routine blood test, liver function, coagulation function, and blood ammonia) were conducted at each visit. The spleen size and patency of bypass vein were assessed with ultrasound and CT.

2.2. Ethical statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All infants’ guardians signed their informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

3. Results

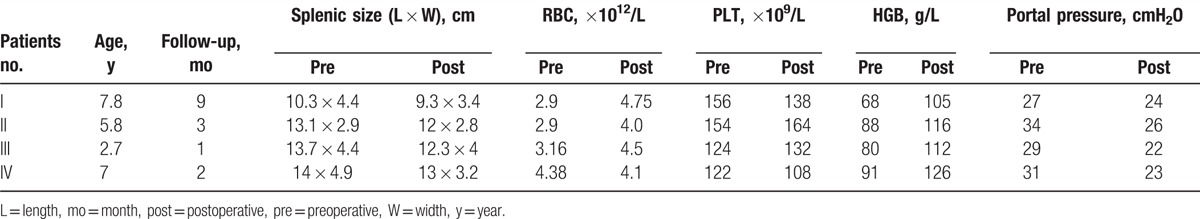

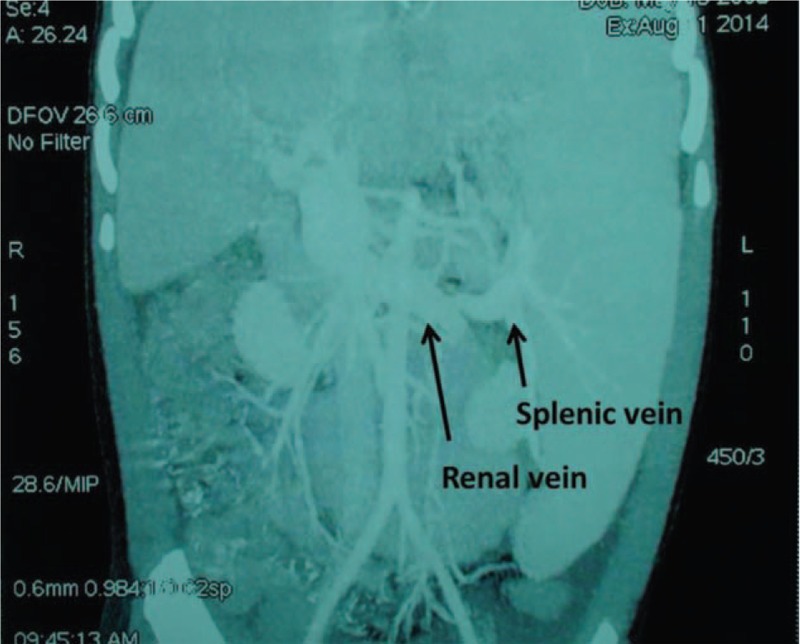

The laparoscopic distal splenoadrenal shunt was successfully performed in all 4 patients. No conversion was required. The liver fibrosis was diagnosed by postoperative liver pathology. The operative time was between 180 and 360 minutes (mean: 270 minutes). The blood loss was minimal without necessity for blood transfusion. The postoperative hospital stay was 6 to 13 days (mean: 8.5 days). The anastomotic diameter was 0.5 to 1 cm (mean: 0.73 cm). The duration of follow-up was 1 to 9 months (mean: 3.8 months). The levels of red blood cell, platelet and white blood cell returned to normal postoperatively. The liver function was normal after the surgeries (the average of alanine aminotransferase: preoperative: 22.3 U/L, postoperative: 28.5 U/L). The portal pressure and size of spleen was reduced after surgery (Table 1). There was no rebleeding. The patency of bypass vein was shown by postoperative sonography and CT (Fig. 7).

Table 1.

The pre- and postoperative parameters of the patients.

Figure 7.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography confirmed patency of the bypass (6 months postoperative).

4. Discussion

Liver fibrosis is the common endpoint of liver disease, which is not a rare disease in children. Currently, there is no effective therapy for liver fibrosis. Liver fibrosis is one of the main causes of intrahepatic portal hypertension in children.[7] Variceal hemorrhage caused by portal hypertension is an important complication of liver fibrosis in children. Management of variceal hemorrhage secondary to portal hypertension includes medical interventions, endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) and sclerotherapy, devascularization, and shunting procedures. About 15% of patients suffered from recurrence of bleeding after medical therapy. The varices disappeared in only 11.8% children undergoing the sclerotherapy.[8] Rebleeding rate of 27.8% and esophageal varies recurrence rate of 44.4% have been reported in children undergoing EVL.[9] Splenectomy can effectively relieve the hypersplenism. However, children undergoing splenectomy are susceptible to overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI) and portal venous thrombosis.[10] The incidence of portal vein thrombosis varied from 1.6% to 15% after splenectomy.[11,12] In addition, Ikeda et al[13] observed a higher incidence of portal vein thrombosis after laparoscopy than after laparotomy, which might be related with the effects of pneumoperitoneum and the laparoscopic stapling technique for vessels. The shunting procedures include selective and nonselective shunt. However, the nonselective shunt (such as mesocaval shunt and portaocaval shunt) diverts a significant amount of portal venous blood from its normal liver metabolism, predisposing the development of hepatic encephalopathy. Fifty percent rebleeding rate and 53% mortality were reported in children with intrahepatic portal hypertension undergoing nonselective shunt.[14] Warren shunt is a selective shunt, which reduces the splenic pressure and alleviates the hypersplenism through the distal splenorenal bypass. The venous collaterals around the stomach and lower esophagus are decompressed, which reduces the risk of hemorrhage.[15] In addition, the Warren shunt preserves the hepatopetal blood flow, which diminishes the risks of postoperative encephalopathy and liver failure. Long-term patency rates >90% have been reported.

Laparoscopic splenic vessel ligation and splenectomy were used to treat hypersplenism secondary to portal hypertension.[1–3] Laparoscopic splenectomy was first reported in 1991. The advantages of the laparoscopic approach over open surgery include a shorter hospital stay, decreased blood loss, faster recovery, and better cosmesis.[16] However, a higher incidence of portal vein thrombosis after laparoscopy than after laparotomy has been reported.[13] Laparoscopic splenic vessels ligation is a feasible treatment for hypersplenism, which has the advantages of laparoscopic surgery.[2] However, this report has a short-term follow-up and fewer cases, and the long-term outcome need to be further studied. Splenectomy and splenic vessel ligation might reduce the portal pressure, which were mainly used to treat the hypersplenism and splenomegaly. In this study, laparoscopic distal splenoadrenal shunt was used to the treatment of portal hypertension in children, it has the following advantages: clear visual field, reduced tissue trauma, decreased postoperative pain, better cosmetic results, and accelerated patient recovery. However, the operative time of laparoscopic surgery is longer than open surgery; this might be related with the lack of experience and had a learning curve as other laparoscopic procedures. In this study, the portal pressure and splenic size was reduced after surgery, which suggested this procedure is a feasible and effective treatment for portal hypertension. However, this study is a preliminary report about laparoscopic splenoadrenal shunt. Further studies with a larger sample size and longer follow-up duration are needed to improve the surgical technique and verify our initial results.

The successful operation was based on the operators’ extensive experience for laparoscopic surgery and the technique of vascular anastomosis. To date, the laparoscopic vascular anastomosis has been rarely reported in children. The challenges of laparoscopic splenoadrenal shunt include: Owing to the retroperitoneal location of splenic and renal vein, the exposure of the surgical field is difficult. We have reported the suspension method and dissection of pancreas in our previous literature.[17,18] In this study, stomach- and pancreas-suspension methods were used to expose the surgical field. The port C (the camera port) forms a triangle with the port A and B, which facilitates triangulation (Fig. 1). In this study, the usage of the vascular clamps and right angle clamp make it possible to do the laparoscopic vascular anastomosis. In this study, the splenic vein was anastomosed with the adrenal vein, which facilitates the blockage of renal vein and avoids the dissection of renal vein. Previous studies have suggested that the splenoadrenal shunt is an effective treatment for children with portal hypertension.[19,20] The splenic artery was clipped before dissection of the splenic vein, and the clamp of the splenic artery was removed after vascular anastomosis, which reduced the bleeding during the operation.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our report suggests that laparoscopic distal splenoadrenal shunt for the treatment of portal hypertension in children is feasible and safe in experienced centers.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, EVL = endoscopic variceal ligation, OPSI = overwhelming postsplenectomy infection, UGI = upper gastrointestinal imaging.

Funding: This study has received funding from Capital Special Health Development Research (Code: 2016-4-2104), Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (Code: 7164242), and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubating Program (Code: PX2016003). Special Research Grant for Non-profit Public Service (Code: 201402007).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Yu H, Guo S, Wang L, et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy and esophagogastric devascularization for liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension is a safe, effective, and minimally invasive operation. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2016;26:524–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhang JS, Li L, Li Q, et al. Laparoscopic splenic vessels ligation as a treatment of hypersplenism and thrombocytopenia in children. Surg Endosc 2016;30:3916–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li SL, Li YC, Xu WL, et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy and periesophagogastric devascularization with endoligature for portal hypertension in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2009;19:545–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McCormick PA, Murphy KM. Splenomegaly, hypersplenism and coagulation abnormalities in liver disease. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2000;14:1009–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Maksoud JG, Miles S, Pinto VC. Distal splenorenal shunt in children. J Pediatr Surg 1978;13:335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Botha JF, Campos BD, Grant WJ, et al. Portosystemic shunts in children: a 15-years experience. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199:179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Grimaldi C, de Ville de Goyet J, Nobili V. Portal hypertension in children. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012;36:260–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bandika VL, Goddard EA, De Lacey RD, et al. Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for bleeding varices in children with intrahepatic and extrahepatic portal venous obstruction: benefit of injection tract embolization. S Afr Med J 2012;102:884–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dos Santos JM, Ferreira AR, Fagundes ED, et al. Endoscopic and pharmacological secondary prophylaxis in children and adolescents with esophageal varices. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;56:93–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Buzelé R, Barbier L, Sauvanet A, et al. Medical complications following splenectomy. J Visc Surg 2016;153:277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Vant Riet M, Burger JW, Van Muiswinkel JM, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of portal vein thrombosis following splenectomy. Br J Surg 2008;87:1229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].He S, He F. Predictive model of portal venous system thrombosis in cirrhotic portal hypertensive patients after splenectomy. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:4236–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Takiguchi S, et al. High incidence of thrombosis of the portal venous system after laparoscopic splenectomy: a prospective study with contrast-enhanced CT scan. Ann Surg 2005;241:208–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fonkalsrud EW. Surgical management of portal hypertension in childhood. Arch Surg 1980;115:1042–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hemann RE, Henderson JM, Vogt DP, et al. Fifty years of surgery for portal hypertension at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation: lessons and prospects. Ann Surg 1995;221:459–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mattioli G, Pini Prato A, Cheli M, et al. Italian multicentric survey on laparoscopic spleen surgery in the pediatric population. Surg Endosc 2007;21:527–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang JS, Li L, Diao M, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic excision of pancreatic tumor in children. J Pediatr Surg 2015;50:882–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhang JS, Li L, Cheng W. Single incision laparoscopic 90% pancreatectomy for the treatment of persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Pediatr Surg Int 2016;32:1003–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mazariegos GV, Reyes J. A technique for distal splenoadrenal shunting in pediatric portal hypertension. J Am Coll Surg 1998;187:634–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gu S, Chang S, Chu J, et al. Spleno-adrenal shunt: a novel alternative for portosystemic decompression in children with portal vein cavernous transformation. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:2189–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]