Abstract

Rationale:

Laparoscopic total pancreatectomy is a complicated surgical procedure and rarely been reported. This study was conducted to investigate the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic total pancreatectomy.

Patients and Methods:

Three patients underwent laparoscopic total pancreatectomy between May 2014 and August 2015. We reviewed their general demographic data, perioperative details, and short-term outcomes. General morbidity was assessed using Clavien–Dindo classification and delayed gastric emptying (DGE) was evaluated by International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition.

Diagnosis and Outcomes:

The indications for laparoscopic total pancreatectomy were intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) (n = 2) and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET) (n = 1). All patients underwent laparoscopic pylorus and spleen-preserving total pancreatectomy, the mean operative time was 490 minutes (range 450–540 minutes), the mean estimated blood loss was 266 mL (range 100–400 minutes); 2 patients suffered from postoperative complication. All the patients recovered uneventfully with conservative treatment and discharged with a mean hospital stay 18 days (range 8–24 days). The short-term (from 108 to 600 days) follow up demonstrated 3 patients had normal and consistent glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level with acceptable quality of life.

Lessons:

Laparoscopic total pancreatectomy is feasible and safe in selected patients and pylorus and spleen preserving technique should be considered. Further prospective randomized studies are needed to obtain a comprehensive understanding the role of laparoscopic technique in total pancreatectomy.

Keywords: laparoscopic techniques, literature review, total pancreatectomy

1. Introduction

Total pancreatectomy is a complicated surgical procedure that combines the operative steps of pancreaticoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy, but facilitates reconstruction and lowers the risk of pancreatic fistula by avoiding the need for a pancreatic anastomosis. In brief, the development of total pancreatectomy could be divided into 3 major periods. Since the first report of total pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma performed by Rockey in 1943,[1] it was considered as an radical surgery in terms of oncology due to the extent of resection.[2] However, after the first enthusiasm over total pancreatectomy, the disadvantages and limited long-term outcome of this surgical strategy became more obvious, which made it seldom performed. Several centers indicated perioperative morbidity and mortality of total pancreatectomy were similar to those of Whipple procedure, but without significant improvement in terms of long-term survival.[3–5] In addition, the metabolic problems resulted from total pancreatectomy made it rarely performed.[6] In recent years, with the development of modern techniques and enzyme preparations, total pancreatectomy could achieve good long-term outcomes and quality of life.[7–9] These improvements made it possible to reappraise total pancreatectomy as a choice of treatment in selected patients in which partial resection is impossible due to the spread of the disease.[10–12]

Nowadays, laparoscopic surgeries have rapidly evolved to include a variety of complex surgical procedures with the advantages of recovery and cosmetic outcomes.[13,14] Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is the most safe and feasible pancreatic procedure, for which there is limited resection and without reconstruction.[15] However, due to the complexity, only a few cases of full laparoscopic and laparoscopic-assisted total pancreatectomy have been reported to date. Here, we report 3 cases of laparoscopic total pancreatectomy with spleen and pylorus preservation and review the current data in terms of this procedure.

2. Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethic Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University. Between May 2014 and August 2015, 2 patients underwent laparoscopic pylorus- and spleen-preserving total pancreatectomy (PpSpTPD) for IPMN; the other patient underwent robotic-assisted PpSpTPD for neuroendocrine tumor and laparoscopic ultrasound-guided liver tumor ablation at West China Hospital, Sichuan University. All the diagnoses were confirmed by CT and postoperative pathology. We reviewed their general demographic data, perioperative details, and short-term outcomes. Outcomes were followed by telephone interview and Internet questionnaire ranged from 108 to 600 days after surgery. General morbidity was assessed using the Clavien–Dindo classification and delayed gastric emptying (DGE) was evaluated by International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition.[16,17]

2.1. Operative technique

2.1.1. Patient positioning and ports placement

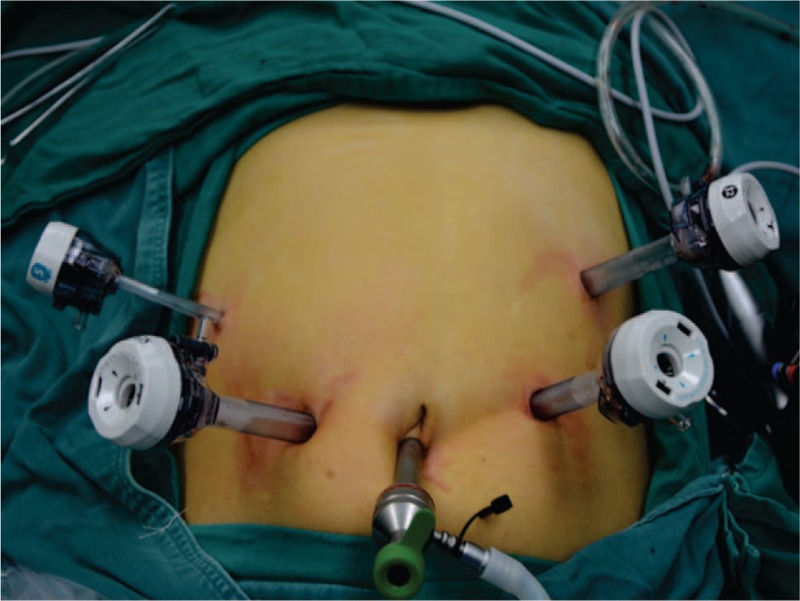

Patients were placed in a supine position with legs split, in a 20° Trendelenburg position. The robotic-assisted system was only applied in the anastomosis part of one patient, therefore there is no difference in terms of Trocar position between the laparoscopic and robotic-assisted technique. At the beginning of surgery, a first 10 mm trocar for 30° of laparoscope was introduced below the umbilicus at the beginning. Four additional trocars were placed to the left and right of the laparoscope trocar: 2 trocars on the right were for the surgeon and the other 2 trocars on the left were for the assistant (Fig. 1). Besides, a small incision (2–3 mm) at the subxiphoid area was created for the retraction of the liver or stomach.

Figure 1.

Trocar placement: 2 trocars on the right for surgeon and 2 trocars on the left for assistant.

2.1.2. Entrance into the lesser sac and division of the duodenum

One patient comorbid with liver tumor underwent laparoscopic ultrasound-guided liver tumor ablation at the beginning of surgery. After the initial exploration, the gastrocolic omentum was widely opened by a harmonic scalpel. Then the posterior stomach was freed from the anterior surface of the pancreas and the right gastroepiploic vessels are identified and divided. The duodenum was transected 3 to 4 cm from pylorus with a laparoscopic linear cutting stapler.

2.2. Mobilization of the pancreatic head and duodenum

The hepatic flexure attachments of the right colon were divided down to the terminal ileum; an extended Kocher maneuver was performed to mobilize the first and second portion of the duodenum, this maneuver also allowed the jejunum to be pulled into the right upper quadrant. The jejunal mesenteric vessels were divided with the LigaSure (Covidien, MA, USA) and the jejunum was transected with a linear cutting stapler approximately 10 cm from the ligament of Treitz.

2.2.1. Division the bile duct and Mobilization of the pancreatic neck

Using the harmonic scalpel, the superior border of the pancreas and the common hepatic artery (CHA) were exposed. Then we routinely cleared lymph nodes and tissue around CHA to aid exposure of the underlying vessel; gastroduodenal artery (GDA) was isolated and divided. A standard cholecystectomy was performed and the bile duct was transected. A tunnel was created underneath the pancreatic neck and through a gentle dissection with tangential movements in relation to the vascular axis. The splenic vein (SV) proximal to the portal vein (PV) was isolated and encircled with a vessel loop, which could facilitate further mobilization of pancreatic body and tail. Another vessel loop was applied to the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) to facilitate the mobilization of pancreatic head.

2.2.2. En bloc mobilization of total pancreas

With the help of retraction on the SMV, the dissection was performed from the lateral border of SMV–PV in a caudal to cephalic direction. Small branches were divided by the LigaSure system. The pancreaticoduodenal veins were clipped and divided. Once the pancreatic head and duodenum were retracted medially to the left, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) was identified posteriorly. Dissection was proceeded along the plane and small branches were served with clips. Then the inferior border of the pancreas was dissected; the dissection began at the inferior margin of the body moving towards the tail. Under the help of splenic vein retraction, small branches were easily isolated and divided. With this maneuver, the specimen was fully detached from the retroperitoneum. Then the specimen was retrieved through a 5-cm periumbilical incision.

2.2.3. Reconstruction and drainage

During the reconstruction, the jejunum was brought up behind the transverse mesocolon and an end-to side hepaticojejunostomy was performed in running suture. Then the duodenojejunostomy was performed in a 2-layer antecolic fashion 50 cm distal to the previous hepaticojejunal anastomosis. Three drainage tubes were left in the vicinity of hepaticojejunostomy, duodenojejunostomy, and hepatorenal recess, respectively.

3. Results

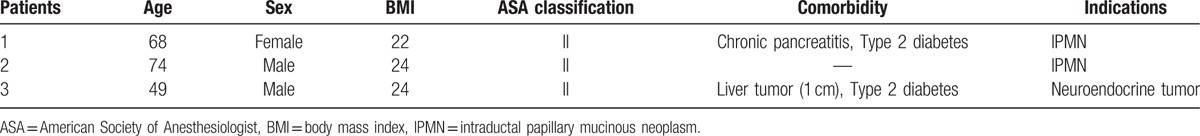

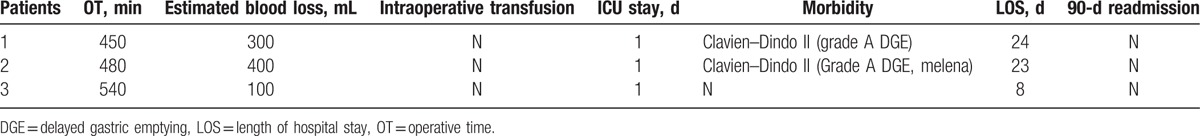

Between May 2014 and August 2015, total pancreatectomy was performed in 3 patients; 2 patients with fully laparoscopic total pancreatectomy, the other patient with laparoscopic total pancreatectomy and robotic-assisted anastomosis. Table 1 demonstrates the demographics and indications. Their mean age was 63 years (range 49–78 years); mean BMI was 23 (range 22–24); All the 3 patients were ASA classification grade II; The third patient with comorbidity of liver tumor (1 cm) was underwent laparoscopic ultrasound-guided tumor ablation at the beginning of surgery. The indications for total pancreatectomy included IPMN (n = 2) and neuroendocrine tumor (n = 1). All the patients underwent pylorus-and spleen-preserving total pancreatectomy. As shown in Table 2, the intraoperative data indicate mean operative time was 490 minutes (range 450–540 minutes), mean estimated blood loss was 266 mL (range 100–400), there is no transfusion during the surgery. In terms of postoperative outcomes, all the patients require 1-day ICU monitoring after surgery. Two patients suffered from postoperative complications (66%): 1 patient suffered from grade A DGE, which required prokinetic medications; the other patient suffered from grade A DGE and melena, which required both prokinetic medications and blood transfusion. All the patients recovered uneventfully and the mean hospital stay was 18 days (range 8–24 days). There is no 90-day mortality and readmission in this study. In terms of the postoperative follow up (range 108–600 days), our study demonstrated 3 patients had normal and consistent glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) level, although 1 patient had slight weight loss and hypoglycemic episodes, all of them had acceptable quality of life.

Table 1.

Patients demographics and indications for TP.

Table 2.

Intraoperative data.

4. Discussion

Because of the absence of pancreatic anastomosis and its radical resection, total pancreatectomy was favored in many surgeons decades ago. But the emerging evidence rapidly mitigated this enthusiasm: although pancreatic fistula was avoided, further quality was worsened because of brittle diabetes. Besides this, it does not improve the cancer-free survival.[9] However, new formulations of endocrine medication and improved understanding of pancreatic disease have made total pancreatectomy an increasingly viable option in the treatment of selected patients. Since the advent of laparoscopic surgery, the advantages were so evident that it quickly became the standard for many surgical indications; however, laparoscopic total pancreatectomy represents one of the most challenging fields in surgery, the reports related laparoscopic total pancreatectomy are still scarce. In our study, we will share our early experience of laparoscopic total pancreatectomy in terms of indication, surgical technique, and postoperative complication.

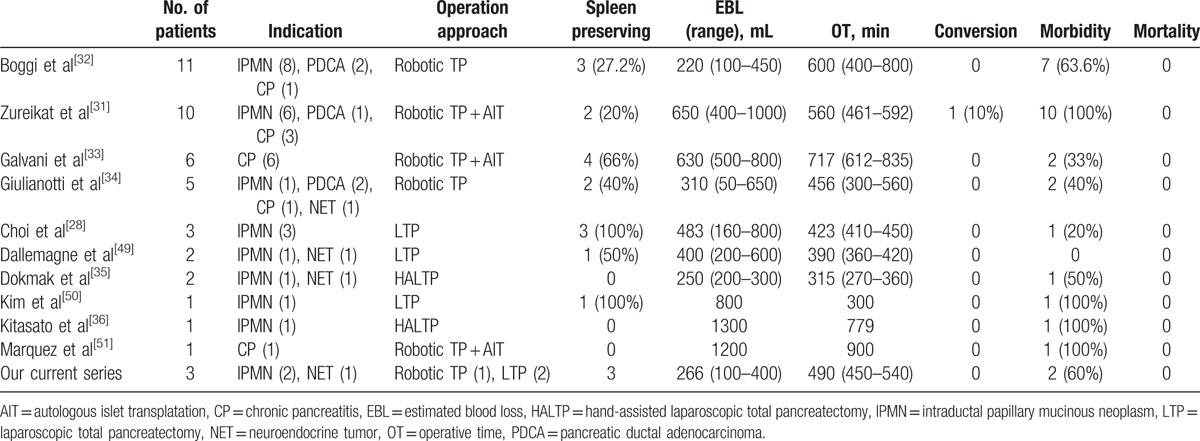

The indications for total pancreatectomy include a variety of disease. Chronic pancreatitis: Warren first performed total pancreatectomy in patients with recurrent pancreatitis and proposed that this procedure is indicated for patients with intractable pain and intraductal obstruction not amenable to a drainage procedure.[18] At that time, the long-term effect is questionable. Nowadays, several center published their excellent pain relief effect of total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis, which made it a reasonable indication for total pancreatectomy.[19,20]Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: historically, sporadic pancreatic cancer was considered as an indication for total pancreatectomy, however, given the recent evidence showing that pancreatic fistulas are now better managed, only 0% to 6% tumors are multicentric[21,22] and this procedure did not provide an increased long-term survival, there is no role for routine consideration of total pancreatectomy as an indication for sporadic pancreatic cancer. On the contrary, in family member with 3 or more first-degree relatives affected by pancreatic cancer, there is a 57-fold increase in the risk of developing familial pancreatic cancer.[23] The susceptibility to pancreatic cancer is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.[24] Evidence showed that surveillance and total pancreatectomy had the potential to avert the development of familial pancreatic cancer and should be considered as a prophylactic procedure in some patients.[25]Neuroendocrine tumors: more and more recent analyses suggest that endocrine tumors always do not have a benign course as previously thought, radical surgery, including total pancreatectomy, to remove locally advanced and metastatic neuroendocrine tumors can improve the duration and quality of life.[26] Therefore, as our understanding of the natural history of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) has improved, it is clear that total pancreatectomy could be applied in selected patients suffering from PNETs. IPMN: it is an intraductal mucin-producing cystic neoplasm of the pancreas with overt malignant potential. In borderline IPMN, a partial pancreatectomy may be considered.[27] However, lesions involving the main pancreatic duct usually have a higher rate of malignancy than those arising from branch duct,[28] about two-thirds of malignant IPMNs become invasive.[29] Therefore, total pancreatectomy should be considered for selected patients with diffuse lesion involving the whole pancreas. There is no difference in terms of indications between laparoscopic and open approaches. In addition, as shown in Table 3, the results from several centers and our present study indicate that IPMN (n = 25) is the primary indication for laparoscopic total pancreatectomy, which comprising 53% patients underwent laparoscopic total pancreatectomy, followed by chronic pancreatitis (n = 12, 27%), pancreatic cancer (n = 5, 11%), and neuroendocrine tumor (n = 4, 9%).

Table 3.

Current studies of laparoscopic/robotic-assisted total pancreatectomy.

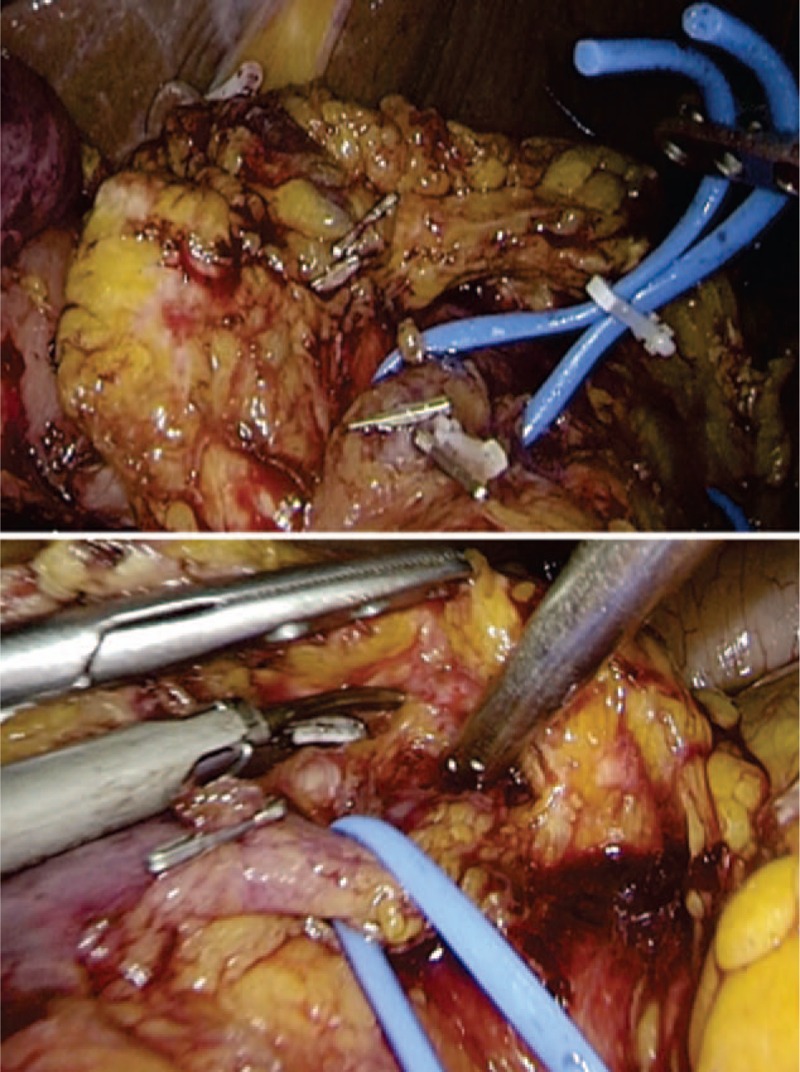

Since the advent of laparoscopy, the advantages of laparoscopic surgery have led it to be the standard for many procedures. However, the pancreatic surgery, especially for total pancreatectomy, is the most challenging technique in laparoscopic surgeries. Therefore, the intraoperative safety is an important concern in terms of laparoscopic total pancreatectomy. To address this problem, several centers[30–33] introduced the robotic-assisted system, which could provide surgeons with precisely dissection of vessels and dexterous reconstruction. Besides, other centers[34,35] used the hand assisted laparoscopic technique or mini-laparotomy to address the limitations of laparoscopy. In our study, robotic system was only applied in one patient for the reconstruction procedure and it is not superior to the laparoscopic technique in terms of anastomosis because the absence of pancreatic anastomosis. In the dissection part, we had 2 strategies to facilitate the fully laparoscopic procedure. As shown in Fig. 2, the first strategy was the application of vascular loops encircled SMV and SV. Because the elasticity of vascular loops, the surgeon could get a perfect retraction without fear of vascular laceration. Besides, the small branches of SMV and SV could be easily spared and clipped. The other strategy, as shown in Fig. 1, is the position of trocars. There are 2 operating trocars on each side, which will facilitate the surgeon and the assistant on each side of patient to cooperate to complete some complicated procedures. For instance, when the major bleeding occurs, assistant could compress the vascular by one hand and expose the bleeding site by the other hand, which would let the surgeon focus on the suture procedure. Therefore, these strategies not only speed up our procedure but also reduce the avoidable bleeding.

Figure 2.

Vascular loop encircled major vein for better retraction and expose: SMV (the upper picture), SV (the lower picture). SMV = superior mesenteric vein, SV = splenic vein.

Pylorus preserving is a concern in pancreatic surgery such as Whipple or total pancreatectomy. In a prospective, randomized, multicenter study, Tran et al[36] demonstrated that there was no difference in terms of operation time, blood loss, and morbidity between the pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) and standard Whipple procedure. In another system review, Karanicolas et al[37] suggested that PPPD was a faster procedure with less intraoperative blood loss compared with standard Whipple procedure. In addition, several early studies[38,39] indicated that pylorus-preserving technique might have an improved nutritional recovery and a better maintenance of the capacity for glucose metabolism. Therefore, pylorus preserving might be beneficial for patients if surgeons could avoid distal gastrectomy in cases of total pancreatectomy without compromising long-term survival. Another issue is whether preserving spleen in total pancreatectomy. In some instance, distal pancreatectomy with simultaneous splenectomy was the surgical choice for tumors located in pancreatic tail because of the anatomic intimacy between the pancreas and the spleen. However, growing understanding in the immunological role of the spleen,[40] along with the long-term complication of splenectomy,[41] led more and more surgeons to avoid splenectomy during pancreatectomies for benign to borderline tumors. Preservation of spleen with distal pancreatectomy can be accomplished in either of 2 ways: by resecting the main splenic artery and vein en bloc with the pancreas but preserving the collateral blood supply of the spleen from short gastric and left gastroepiploic vessels, named Warshaw technique,[42] or by carefully dissecting the pancreas off the splenic vessels, named Kimura technique.[43] Although the Warshaw technique is judged to be safe, fast and associated with reduced intraoperative blood loss, concerns still exist due to the possibility of postoperative splenic infarct and development of gastric varices after division of the splenic vessels.[44] However, there is no significant difference between the 2 techniques in terms of long-term consequence. Therefore, it is worth to attempt spleen preserving total pancreatectomy in selected patients; which technique used for spleen conservation depends on the condition of patient and experience of surgeon.

Due to the absence of pancreatic anastomosis, DGE is one of the most common postoperative complications after total pancreatectomy. The ISGPS developed an objective and generally applicable definition and classification of DGE: the inability to return to a solid diet by the end of the first postoperative week and includes prolonged nasogastric intubation of the patient; 3 grades were defined based on the impact on the clinical course and postoperative management.[17] The mechanism of developing postoperative DGE is poorly understood because of the complex process of gastric emptying. Duodenal resection, leading to decrease of cholecystokinin and other hormones, might be an important factor for DGE[45]; other proposed factors including the occurrence of complications, anatomic alteration, and so on. DGE occurs after both standard (with antrectomy) and pylorus-preserving technique without significant difference.[46] Various strategies have been proposed to reduce the incidence of DGE; in a random, prospective study, Tani et al[47] published that an antecolic duodenojejunostomy might have a lower the occurrence of DGE compared with that of retrocolic method. Moreover, John et al[48] suggested that laparoscopic total pancreatectomy approach lowered length of stay and need for prokinetic medications postoperatively, which indicates a role of laparoscopy in reducing the incidence of DGE. Therefore, standardization of surgical technique and postoperative management are needed to improve the incidence of DGE.

In conclusion, our results are in keeping with a few current studies: laparoscopic total pancreatectomy is feasible and safe in well-selected patients with reasonable indications. In addition, pylorus and spleen preserving should be considered during the operation. Further prospective randomized studies are needed to obtain an objective assessment of laparoscopic total pancreatectomy.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CHA = common hepatic artery, DGE = delayed gastric emptying, GDA = gastroduodenal artery, HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin, IPMN = intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, ISGPS = International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery, PNET = pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, PPPD = pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, PpSpTPD = pylorus- and spleen-preserving total pancreatectomy, PV = portal vein, SMA = superior mesenteric artery, SMV = superior mesenteric vein, SV = splenic vein.

Funding: The study was supported by the West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

XL and BP contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Rockey EW. Total pancreatectomy for carcinoma: case report. Ann Surg 1943;118:603–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].ReMine WH, Priestley JT, Judd ES, et al. Total pancreatectomy. Ann Surg 1970;172:595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Grace PA, Pitt HA, Tompkins RK, et al. Decreased morbidity and mortality after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 1986;151:141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sarr MG, Behrns KE, van Heerden JA. Total pancreatectomy. An objective analysis of its use in pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 1993;40:418–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].McAfee MK, van Heerden JA, Adson MA. Is proximal pancreatoduodenectomy with pyloric preservation superior to total pancreatectomy? Surgery 1989;105:347–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dresler CM, Fortner JG, McDermott K, et al. Metabolic consequences of (regional) total pancreatectomy. Ann Surg 1991;214:131–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wilson GC, Sutton JM, Abbott DE, et al. Long-term outcomes after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplantation: is it a durable operation? Ann Surg 2014;260:659–65. discussion 657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Watanabe Y, Ohtsuka T, Matsunaga T, et al. Long-term outcomes after total pancreatectomy: special reference to survivors’ living conditions and quality of life. World J Surg 2015;39:1231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Reddy S, Wolfgang CL, Cameron JL, et al. Total pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: evaluation of morbidity and long-term survival. Ann Surg 2009;250:282–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Clayton HA, Davies JE, Pollard CA, et al. Pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation for the treatment of severe chronic pancreatitis: the first 40 patients at the leicester general hospital. Transplantation 2003;76:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cuillerier E, Cellier C, Palazzo L, et al. Outcome after surgical resection of intraductal papillary and mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:441–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wente MN, Kleeff J, Esposito I, et al. Renal cancer cell metastasis into the pancreas: a single-center experience and overview of the literature. Pancreas 2005;30:218–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rosenthal RJ, Diaz AA, et al. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Venkat R, Edil BH, Schulick RD, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is associated with significantly less overall morbidity compared to the open technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2012;255:1048–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250:187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007;142:761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Warren KW, Poulantzas JK, Kune GA. Life after total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis: clinical study of eight cases. Ann Surg 1966;164:830–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE, Dunn DL, et al. Transplant options for patients undergoing total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg 2004;198:559–67. discussion 559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rodriguez Rilo HL, Ahmad SA, D’Alessio D, et al. Total pancreatectomy and autologous islet cell transplantation as a means to treat severe chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:978–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kloppel G, Lohse T, Bosslet K, et al. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: incidence of tumor involvement beyond the Whipple resection line. Histological and immunocytochemical analysis of 37 total pancreatectomy specimens. Pancreas 1987;2:170–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Motojima K, Urano T, Nagata Y, et al. Detection of point mutations in the Kirsten-ras oncogene provides evidence for the multicentricity of pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg 1993;217:138–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bartsch DK. Familial pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2003;90:386–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lynch HT, Lanspa SJ, Fitzgibbons RJ, Jr, et al. Familial pancreatic cancer (Part 1): genetic pathology review. Nebr Med J 1989;74:109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Charpentier KP, Brentnall TA, Bronner MP, et al. A new indication for pancreas transplantation: high grade pancreatic dysplasia. Clin Transplant 2004;18:105–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Norton JA, Kivlen M, Li M, et al. Morbidity and mortality of aggressive resection in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. Arch Surg 2003;138:859–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Choi SH, Hwang HK, Kang CM, et al. Pylorus- and spleen-preserving total pancreatoduodenectomy with resection of both whole splenic vessels: feasibility and laparoscopic application to intraductal papillary mucin-producing tumors of the pancreas. Surg Endosc 2012;26:2072–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Obara T, Maguchi H, Saitoh Y, et al. Mucin-producing tumor of the pancreas: natural history and serial pancreatogram changes. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:564–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2006;6:17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zureikat AH, Nguyen T, Boone BA, et al. Robotic total pancreatectomy with or without autologous islet cell transplantation: replication of an open technique through a minimal access approach. Surg Endosc 2015;29:176–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Boggi U, Palladino S, Massimetti G, et al. Laparoscopic robot-assisted versus open total pancreatectomy: a case-matched study. Surg Endosc 2015;29:1425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Galvani CA, Rodriguez Rilo H, Samame J, et al. Fully robotic-assisted technique for total pancreatectomy with an autologous islet transplant in chronic pancreatitis patients: results of a first series. J Am Coll Surg 2014;218:e73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Giulianotti PC, Addeo P, Buchs NC, et al. Early experience with robotic total pancreatectomy. Pancreas 2011;40:311–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dokmak S, Aussilhou B, Sauvanet A, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic total pancreatectomy: a report of two cases. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2013;23:539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kitasato A, Tajima Y, Kuroki T, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic total pancreatectomy for a main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Surg Today 2011;41:306–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tran KT, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, et al. Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure: a prospective, randomized, multicenter analysis of 170 patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumors. Ann Surg 2004;240:738–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Karanicolas PJ, Davies E, Kunz R, et al. The pylorus: take it or leave it? Systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus standard whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:1825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Pylorus-preserving total pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. World J Surg 2000;24:66–70. discussion 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Agnifili A, Marino M, Verzaro R, et al. [Pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy allows a better maintenance of glucose homeostasis]. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 1997;43:135–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kruetzmann S, Rosado MM, Weber H, et al. Human immunoglobulin M memory B cells controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are generated in the spleen. J Exp Med 2003;197:939–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cadili A, de Gara C. Complications of splenectomy. Am J Med 2008;121:371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Warshaw AL. Conservation of the spleen with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg 1988;123:550–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kimura W, Inoue T, Futakawa N, et al. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with conservation of the splenic artery and vein. Surgery 1996;120:885–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Miura F, Takada T, Asano T, et al. Hemodynamic changes of splenogastric circulation after spleen-preserving pancreatectomy with excision of splenic artery and vein. Surgery 2005;138:518–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Muller MW, Friess H, Beger HG, et al. Gastric emptying following pylorus-preserving Whipple and duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg 1997;173:257–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Gulik TM, DeWit LT, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after standard pancreaticoduodenectomy versus pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: an analysis of 200 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg 1997;185:373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Tani M, Terasawa H, Kawai M, et al. Improvement of delayed gastric emptying in pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg 2006;243:316–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].John GK, Singh VK, Pasricha PJ, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) following total pancreatectomy with islet auto transplantation in patients with chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg 2015;19:1256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Dallemagne B, de Oliveira AT, Lacerda CF, et al. Full laparoscopic total pancreatectomy with and without spleen and pylorus preservation: a feasibility report. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013;20:647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kim DH, Kang CM, Lee WJ. Laparoscopic-assisted spleen-preserving and pylorus-preserving total pancreatectomy for main duct type intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: a case report. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2011;21:179–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Marquez S, Marquez TT, Ikramuddin S, et al. Laparoscopic and da Vinci robot-assisted total pancreaticoduodenectomy and intraportal islet autotransplantation: case report of a definitive minimally invasive treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 2010;39:1109–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]