Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether there is a difference in balance function between older persons with and without diabetes mellitus (DM), and to identify whether mediating factors, such as diabetic complications, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) score, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, as well as hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), serum total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), are associated with balance function in older persons with DM.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 208 older persons were divided into a DM group (n=80) and a control group who did not have DM (n=128). Balance function was evaluated with the Tinetti performance-oriented mobility assessment (POMA), which includes balance and gait subscales. Activities of daily living (ADL), IADL, and the MMSE were also measured. Fall incidents in last 12 months, the use of walking aids, fear of falling, comorbidities, and polypharmacy were recorded. Diabetic complications were recorded, and HbA1c, FPG, TC, TG, and LDL were measured in the patients of the DM group.

Results

Fall incidents in last 12 months were higher in the DM group than in the control group (P<0.01). POMA score as well as ADL and IADL scores were lower in the diabetic group than the control group (P<0.05). Within the diabetic group, the POMA score was positively related to the ADL score (odds ratio [OR], 11.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.076–44.497; P<0.01), IADL score (OR, 16.286; 95% CI, 4.793–55.333; P<0.01), and MMSE score (OR, 10.524; 95% CI, 2.764–40.074; P<0.01), but was negatively related to age (OR, 7.707; 95% CI, 2.035–29.185; P<0.01) and diabetic complication (OR, 6.667; 95% CI, 2.279–19.504; P<0.01). Also, within the DM group, the decreased POMA score was associated with multiple diabetic complications (OR, 5.977; 95% CI, 1.378–25.926; P<0.05), decreased IADL score (OR, 10.288; 95% CI, 2.410–43.915; P<0.01), and MMSE score (OR, 13.757; 95% CI, 2.556–74.048; P<0.01).

Conclusion

Multiple diabetic complications, lower MMSE, ADL, and IADL scores were associated with declining balance function in the older persons with DM. These findings can alert physicians to detect and intervene earlier on declining balance in older persons with DM.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, balance, POMA, fall, elderly, performance-oriented mobility assessment

Introduction

Falls are the main cause of both fatal and nonfatal injuries in the elderly,1 such as fractures and cerebral trauma, which increase morbidity and mortality and raise health care costs.2,3 Diabetes mellitus (DM) affects >300 million individuals worldwide, ~20% of adults aged between 65 and 76 years have diabetes, and this prevalence will continue to increase with population aging.4 The risk of falling is higher in older persons with DM.5–6 An interdisciplinary cohort study from the Netherlands showed that older individuals with diabetes had a 67% higher risk of recurrent falls than their counterparts without DM.7 DM has been identified as a risk factor for falls and fall-related injuries and fractures in a number of prospective studies.5,8–9 Due to the prevalence of DM in the older population and the evidence of higher risk of falls among older diabetic patients,7–8 further investigation of risk factors for falls in these patients is needed.

Falls can result from internal and external factors. Unsafe environmental conditions are among the external factors, which sometimes could not be avoided, whereas other factors such as impaired physical and mental function, polypharmacy, comorbidities, or fear of falls are some of the intrinsic ones.10 Poor balance has been determined as a major risk factor for falls in old adults.11 Many diabetes-related complications have proven to be associated with high risks of falls.12–13 However, there were very few studies about the relationship between DM and balance function in the older people. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate whether there is a difference in balance function between old adults with and without diabetes and to identify possible mediating factors. This could assist in designing tailored fall prevention programs for this population.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this cross-sectional study, 80 diabetic patients aged >65 years and 128 old people without DM were recruited from the geriatric ward of Zhejiang Hospital between September 2013 and September 2014. The balance function of all the old patients was evaluated utilizing Tinetti performance-oriented mobility assessment (POMA)14 by a trained geriatric nurse. A comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) was performed by a trained geriatric nurse and a geriatrician within 3 days after the admission of each qualified patient in our ward. The main content of CGA included a general health questionnaire, assessment of activities of daily living (ADL),15 Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL),16 Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),17 and the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF).18 Assessment of grip strength, fall incidents in the last 12 months, the use of walking aids, fear of falling, comorbidities, and number of medication were recorded. For the older persons with DM, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), serum total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) were measured and recorded. Approval for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

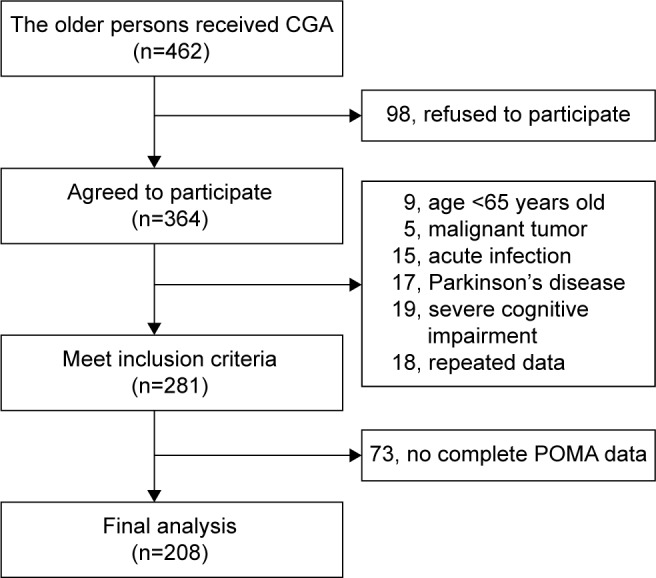

A total of 462 potential cases were identified. All the patients were from geriatric ward and received the CGA between September 2013 and September 2014. Also, 364 participants agreed to take part in the study. Among the 364 cases, 9 patients were excluded because of their age, who were <65 years; 5 patients were not included because of malignant tumor; 15 patients were not included as a result of acute infection; 17 patients were excluded due to Parkinson’s disease (PD); 19 patients were excluded due to severe cognitive decline; 18 patients’ data which were found repeated were excluded; and 73 patients who did not have complete data on the POMA were excluded. All the remaining 208 cases were used for analysis. Figure 1 shows the procedure of selecting patients.

Figure 1.

The procedure of patient selection.

Abbreviations: CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment; POMA, performance-oriented mobility assessment.

All participants with DM were diagnosed by experienced physicians according to the criterion of diagnosis and classification of DM made by the World Health Organization (WHO) consultation.19 Diabetic complications included diabetic macroangiopathy, diabetic nephropathy (DN), diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), and diabetic retinopathy (DR) in this study. With each complication marked as 1 point, the diabetic complication score ranged from 0 to 4. Diabetic macroangiopathy was considered as having any of the following diseases: 1) ischemic heart disease (IHD), which was diagnosed based on a coronary angiogram or a history of physician-treated IHD; 2) cerebrovascular accident (CVA), which was diagnosed based on history, clinical examination, or history of physician-treated CVA, or previous computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging records; and 3) peripheral vascular disease (PVD), which was diagnosed clinically based on the history of PVD or carotid artery/femoral artery ultrasound records. The diagnosis of DN was based on the 24-hour urine protein estimation or the urinary albumin creatinine ratio (≥30 μg/mg) or medical records. The diagnosis of DPN was based on symptoms such as numbness or stabbing pain of the limbs and abnormal electromyography (≥3 different sensory or motor nerves impairment) or by reviewing the medical diagnosis records. The diagnosis of DR was made by a retinal specialist based on a dilated pupil using direct ophthalmoscopy using the early treatment DR study grading system.

The inclusion criteria were aged ≥65 years, ability to understand and communicate in Chinese, ability to walk without personal assistance (walking aids permitted), and hearing and vision sufficient for compliance with assessment. Participants with acute infection, malignant tumor, PD, diabetic foot, cerebellum diseases, acute cerebrovascular diseases, delirium, terminal illness, severe vision or hearing deficits, or severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score ≤12) were excluded from the study.

Data collection

Sociodemographic data, including age, sex, body weight (kg), and body height (m), were collected. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated by measuring body weight (kg) and body height (m). Information about concomitant diseases, diabetic complications, and the usage of medication was recorded by reviewing the hospital medical records. Comorbidities were defined as not less than five kinds of diseases. Patients who took five or more oral prescription drugs were regarded as experiencing polypharmacy.20 The ADL and IADL were used to assess functional status. The cognitive status was evaluated by the MMSE. The MNA-SF was used to assess the nutritional status. Venous blood samples were collected early in the morning from resting fasting patients. HbA1c, FPG, TC, TG, and LDL were tested in the laboratory of Zhejiang Hospital.

Balance assessment

The Tinetti POMA scale was used for evaluating balance function. All participants were asked to walk as briskly as possible with or without walking aids during the assessment. The POMA scale contains two parts: balance and gait. 1) The balance subscale includes nine components (sitting balance, arises, attempts to arise, immediate standing balance, standing balance, nudged, eyes closed, turning 360°, and sitting down; maximum 16 points); 2) the gait subscale consists of seven components (initiation of gait, step length, step symmetry, step continuity, path, trunk, and walking stance; maximum 12 points).21 And each subscale was measured as abnormal =0 or normal =1; in some cases, adaptive =1 and normal =2. The total score is associated with different levels of balance function, from low level (0–24) to medium or high level (25–28).

Statistical analysis

The variables were analyzed by using the SPSS 22.0 software. Conforming to the normal distribution, continuous variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD); conforming to the abnormal distribution, continuous variables were presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as a percentage or constituent ratio. The independent sample t-test (for normally distributed continuous data), the chi-square test (for categorical data), and the Mann–Whitney U test (for abnormally distributed continuous data) were used to compare the statistical difference between DM group and non-DM group. As a secondary analysis, scores of each assessment were treated as continuous variables. The relationship between POMA score and other potential mediating risk factors were analyzed by univariated logistic regression analysis. Binary logistic regression analysis was used for further analysis about the association between POMA score and potential mediating risk factors, adjusting age, fear of falling, history of falls in last 12 months. Odds ratios (ORs) are reported for significant associations. All significance tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was assumed as P<0.05.

Results

Of the 208 elderly participants recruited in the study, 80 were diagnosed with DM and 128 were in the control group. Compared to controls, participants with DM were more likely to have falls in the last 12 months, had a lower score of POMA, which reflected the balance function, and had worse scores of ADL and IADL, which reflected physical function. The MMSE score that reflected mental function and the MNA-SF score that reflected nutritional status of DM group were also lower than those of the control group, although the differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical data between diabetes mellitus and control groups

| Characteristics | DM (n=80) |

Controls (n=128) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age (years), mean ± SDa | 79.4±7.2 | 78.4±7.1 | 0.337 |

| Gender (men), n (%) | 43 (53.8) | 73 (57.0) | 0.644 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SDa | 24.5±3.2 | 23.3±3.2 | 0.989 |

| Medical | |||

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 41 (51.2) | 70 (54.7) | 0.630 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 28 (35.0) | 37 (28.9) | 0.357 |

| Renal disease, n (%) | 9 (11.3) | 20 (15.6) | 0.377 |

| Musculoskeletal disease, n (%) | 23 (28.8) | 49 (38.3) | 0.161 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 35 (43.8) | 68 (53.1) | 0.189 |

| Polypharmacy, n (%) | 35 (43.8) | 55 (43.0) | 0.912 |

| History of falls, n (%) | 29 (36.3) | 21 (16.4) | 0.001 |

| Fear of falling, n (%) | 34 (42.5) | 41 (32.0) | 0.127 |

| Walking aids, n (%) | 12 (15.0) | 18 (14.1) | 0.852 |

| POMA (IQR)b | 25 (21–26) | 25 (23–27) | 0.013 |

| ADL (IQR)b | 100 (95–100) | 100 (95–100) | 0.044 |

| IADL (IQR)b | 7 (4–8) | 8 (6–8) | 0.003 |

| MMSE (IQR)b | 26 (24–28) | 27 (25–29) | 0.100 |

| MNA-SF (IQR)b | 13 (12–14) | 13 (11–14) | 0.110 |

Notes: All data were analyzed by the chi-square test unless marked.

The independent samples t-test.

The Mann–Whitney U test.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; IQR, interquartile range; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form; POMA, performance-oriented mobility assessment; SD, standard deviation.

Risk factors which might have a relationship with the POMA score within the DM patients were investigated. First, POMA scores were divided into the low-level group (0–24) and the medium- to high-level group (25–28). Age was divided into older group (age ≥75 years) and old group (65–74 years). BMI was divided into the overweight group (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) and the normal group (BMI <25 kg/m2). Diabetic complication scores were divided into multiple complications group (3–4) and normal or lesser complications group (0–2). HbA1c was divided into abnormal group (HbA1c ≥6.5%) and normal group (HbA1c <6.5%). FPG was divided into high-level group (FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L) and low-level group (FPG <7.0 mmol/L). TG was divided into abnormal group (TG ≥1.7 mmol/L) and normal group (TG <1.7 mmol/L). TC was divided into abnormal group (TC ≥3.11 mmol/L) and normal group (TC <3.11 mmol/L). LDL was divided into abnormal group (LDL ≥2.07 mmol/L) and normal group (LDL <2.07 mmol/L). ADL scores were divided into dependent group (ADL ≤95) and independent group (ADL >95). IADL scores were divided into low-level group (0–5) and high-level group (6–8). MMSE scores were divided into abnormal range group (0–24) and normal range group (25–30). Second, each risk factor was analyzed by univariate logistic regression analysis. Finally, the results showed that the POMA score had a positive relationship with ADL (OR: 11.700, 95% CI: 3.076–44.497, P<0.01), IADL (OR: 16.286, 95% CI: 4.793–55.333, P<0.01), MMSE (OR: 10.524, 95% CI: 2.764–40.075, P<0.01), and MNA-SF (OR: 2.769, 95% CI: 0.920–8.337, P<0.1; Table 2) and had a negative relationship with age (OR: 7.707, 95% CI: 2.035–29.185, P<0.01) and diabetic complications score (OR: 6.667, 95% CI: 2.279–19.504, P<0.01; Table 2). However, POMA score had no obvious relationship with HbA1c, FPG, TC, TG, and LDL levels in this study.

Table 2.

Association between POMA score and univariate risk factors in older diabetic patients

| Risk factor | POMA

|

|

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 7.707 (2.035–29.185) | 0.003 |

| Gender | 0.918 (0.381–2.213) | 0.849 |

| BMI | 1.200 (0.496–2.901) | 0.686 |

| History of falls | 2.024 (0.802–5.108) | 0.136 |

| Walking aids | 0.758 (0.219–2.624) | 0.661 |

| Fear of falling | 0.520 (0.211–1.283) | 0.159 |

| Polypharmacy | 1.625 (0.667–3.957) | 0.285 |

| Use of insulin | 1.838 (0.713–4.737) | 0.208 |

| Diabetic complications score | 6.667 (2.279–19.504) | 0.001 |

| HbA1c | 0.918 (0.381–2.213) | 0.847 |

| FPG | 0.618 (0.250–1.528) | 0.297 |

| TG | 1.600 (0.500–5.125) | 0.429 |

| TC | 0.429 (0.102–1.793) | 0.246 |

| LDL | 0.411 (0.075–2.257) | 0.306 |

| ADL | 11.700 (3.076–44.497) | 0.000 |

| IADL | 16.286 (4.793–55.333) | 0.000 |

| MMSE | 10.524 (2.764–40.075) | 0.001 |

| MNA-SF | 2.769 (0.920–8.337) | 0.070 |

Note: Each risk factor was analyzed by univariate logistic regression analysis.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form; OR, odds ratio; POMA, performance-oriented mobility assessment; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Then, in the final step, the binary classification of the POMA score was treated as a dependent variable, and the binary classification of the diabetic complication score, ADL score, IADL score, MMSE score, and MNA-SF score, which were treated as covariates (Table 2; P<0.1), were separately entered with POMA into the stepwise multivariate logistic regression model after adjusting for age, history of falls, and fear of falling (Table 2; P<0.2). The results showed that the decreased POMA score which represent impaired balance function was associated with multiple diabetic complications (OR: 5.977, 95% CI: 1.378–25.926, P<0.05), IADL impairment (OR: 10.288, 95% CI: 2.410–43.915, P<0.01), and MMSE impairment (OR: 13.757, 95% CI: 2.556–74.048, P<0.01; Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between POMA score and other risk factors in elderly diabetic patients

| POMA

|

||

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 5.279 (0.872–31.965) | 0.070 |

| Fear of falling | 0.712 (0.184–2.761) | 0.627 |

| History of falls | 0.490 (0.110–2.190) | 0.351 |

| Diabetic complication score | 5.977 (1.378–25.926) | 0.017 |

| IADL | 10.288 (2.410–43.915) | 0.002 |

| MMSE | 13.757 (2.556–74.048) | 0.002 |

Notes: All data were analyzed by binary logistic regression analysis with adjustment for age, fear of falling, and history of falls. Age was divided into the older group (age ≥75 years) and the old group (65–74 years); POMA scores were divided into the low-level group (0–24) and the medium- or high-level group (25–28); diabetic complication scores were divided into the multiple complications group (3–4) and the normal or lesser complications group (0–2); IADL scores were divided into the abnormal range group (0–5) and the normal range group (6–8); MMSE scores were divided into the abnormal range group (0–24) and the normal range group (25–30).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; OR, odds ratio; POMA, performance-oriented mobility assessment.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that multiple diabetic complications, lower scores of IADL and MMSE were associated with the decline of balance function in elderly patients with DM.

In this study, elderly patients with diabetes had more fall incidents in the last 12 months compared to those without DM. Our results confirmed previous findings about a higher prevalence of falls in the elderly diabetic patients.7,22–25 We also found that compared with the elderly participants without DM, the elderly diabetic patients got lower score of POMA, which reflected the balance function. The results were consistent with those obtained in previous studies. Maurer5 reported that individuals with DM frequently complain of feeling dizziness and unstable and often exhibit impairments in balance, sensory capacity, and gait, with the consequence of increased risk of falling. It was suggested by Petrofsky26 that people with DM displayed significantly more sway than those healthy control subjects while standing on a balance platform. In addition, Morrison27 found that exercise improves balance and gait in older persons with type 2 DM. Apart from these, participants with DM were more likely to have lower scores of ADL and IADL in our study. The elderly adults with DM were more likely to develop a series of diabetic complications. It is well known that DM could affect renal, neurological, and cardiovascular systems and the association of DM with complications could lead to physical disability.24 Although physical and mental function decrease with aging, the coexistence of DM and diabetic complications could accelerate the process or make the physical and mental conditions even worse.28 Previous studies have shown that both declining physical29 and cognitive function30 might affect balance function. Pijpers7 found risk factors that partly increase fall incidents in older diabetic patients included limitations in ADLs, impaired physical performance (including balance and gait), and cognitive impairment. This might explain why DM participants in our study got lower scores of ADL, IADL, MMSE, and POMA, although the MMSE score difference between diabetic and control groups did not reach the statistical significance.

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, the results showed that POMA score had a positive relationship with ADL, IADL, MMSE, and MNA-SF and had a negative relationship with age and diabetic complications score. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed the decreased POMA score, which represented that balance impairment was only associated with multiple diabetic complications, decreased IADL score, and lower MMSE score. Although many studies had shown strong positive associations between elevated HbA1c, FPG, TC, TG, or LDL levels and chronic complication risks in diabetic patients, however, HbA1c, FPG, TC, TG, and LDL levels were not associated with the decreased POMA score in this study. It might be because group characteristics in previous studies were different from our study. In this study, the average age of the group was >79 years, and most of them had already gotten diabetic complications and other metabolic-related diseases.

More studies about functional status in older diabetics need to be done in the future. Beyond control of blood glucose and blood lipid, we also need to pay more attention to function status in the older diabetic patients in China. Our findings could alert physicians to detect and intervene earlier on declining balance in older persons with DM, and it might be an easier and faster way to screen those kinds of patients.

There are a few limitations of this study. 1) Our study was based on cross-sectional data, which may be limited by bias from inter-individual variability or cohort effects. Due to the feature of cross-sectional study, a causal association among the four variables, namely, POMA score, diabetic complication score, IADL score, and MMSE score, could not be directly concluded. Prospective studies will be required to determine whether old diabetic patients who got multiple diabetic complications and worse MMSE score or worse IADL score would have impaired balance function. 2) Although diabetic complication was considered as one of the mediating factors that might affect the balance function of old diabetic patients, however, we just analyze the relationship between the number of complications and impaired balance function, further studies will be required to determine whether each diabetic complication, such as DN, DPN, or DR, will have relationship with impaired balance function by enlarging the samples’ quantity. Also, we could investigate the possible mediating factors in the future study.

Despite these limitations, this study had several strengths. Most of the previous studies aimed to investigate related factors of falls; however, falls can result from internal and external factors. Unsafe environmental conditions are among the external factors, which sometimes are difficult to avoid, and the elderly people’s memories about fall incidents may have bias through inquiry. Excluding the external factors, the factor that lead to fall and can be measured directly is the elderly patient’s balance function. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the associated factors about impaired balance function in the elderly diabetic patients. Besides this, our study was a considerable large group of elderly patients with specific disease who underwent the CGA. The CGA that could systematically evaluate the functional status of the elderly has not yet been widely applied in clinical in China, especially in the diabetic patients whose average age was >75 years, thus we are among the first to investigate related factors about impaired balance function through CGA in the very older diabetic patients.

Conclusion

This study suggests that multiple diabetic complications and impaired physical and mental function are associated with declining balance function in older diabetic patients. Our findings could alert physicians to detect and intervene earlier on declining balance in older persons with DM. Further study is warranted to investigate the possible mechanisms of the observed associations and whether interventions for improving physical and mental function as well as treatment for diabetic complications could increase balance function in the elderly diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by innovation disciplines of Zhejiang Province and funds from National Health and Family Planning Commission of Scientific Research (WKJ2013-2-001) as well as Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2014C33241) to Xujiao Chen and from Zhejiang Province Association of Traditional Chinese Medcine (2016ZB012) to Xiufang Hong.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Stevens JA, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ, Ballesteros MF. Self-reported falls and fall-related injuries among persons aged≥65 years – United States, 2006. J Safety Res. 2008;39(3):345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher PC, Guthrie DM, Berg K, et al. Risk factors for restriction in activity associated with fear of falling among seniors within the community. J Patient Saf. 2010;6(3):187–191. doi: 10.1097/pts.0b013e3181f1251c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scuffham P, Chaplin S, Legood R. Incidence and costs of unintentional falls in older people in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(9):740–744. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.9.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunning T, Sinclair A, Colagiuri S. New IDF guideline for managing type 2 diabetes in older people. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(3):538–540. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurer MS, Burcham J, Cheng H. Diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of falls in elderly residents of a long-term care facility. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(9):1157–1162. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.9.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanlon JT, Landerman LR, Fillenbaum GG, Studenski S. Falls in African American and white community-dwelling elderly residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(7):M473–M478. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.7.m473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pijpers E, Ferreira I, de Jongh RT, et al. Older individuals with diabetes have an increased risk of recurrent falls: analysis of potential mediating factors: the longitudinal ageing study Amsterdam. Age Ageing. 2012;41(3):358–365. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volpato S, Leveille SG, Blaum C, Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Risk factors for falls in older disabled women with diabetes: the women’s health and aging study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(12):1539–1545. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.12.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strotmeyer ES, Cauley JA, Schwartz AV, et al. Nontraumatic fracture risk with diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose in older white and black adults: the health, aging, and body composition study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(14):1612–1617. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Menezes RL, Bachion MM. Study of intrinsic risk factors for falls in institutionalized elderly people. Cien Saude Colet. 2008;13(4):1209–1218. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232008000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sturnieks DL, St George R, Lord SR. Balance disorders in the elderly. Neurophysiol Clin. 2008;38(6):467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tilling LM, Darawil K, Britton M. Falls as a complication of diabetes mellitus in older people. J Diabetes Complications. 2006;20(3):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz AV, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE, et al. Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study Diabetes-related complications, glycemic control, and falls in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):391–396. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(13):821–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lobo A, Ezquerra J, Gomez Burgada F, Sala JM, Seva Díaz A. Cognocitive mini-test (a simple practical test to detect intellectual changes in medical patients) Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines. 1979;7(3):189–202. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salvà A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for under-nutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF) J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M366–M372. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.6.m366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15(7):539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(2):187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(2):119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb05480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryerson B, Tierney EF, Thompson TJ, et al. Excess physical limitations among adults with diabetes in the U.S. population, 1997–1999. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(1):206–210. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz AV, Hillier TA, Sellmeyer DE, et al. Older women with diabetes have a higher risk of falls: a prospective study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1749–1754. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu FP, Lin KP, Kuo HK. Diabetes and the risk of multi-system aging phenotypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quandt SA, Stafford JM, Bell RA, Smith SL, Snively BM, Arcury TA. Predictors of falls in a multiethnic population of older rural adults with diabetes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(4):394–398. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrofsky JS, Cuneo M, Lee S, Johnson E, Lohman E. Correlation between gait and balance in people with and without type 2 diabetes in normal and subdued light. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12(7):CR273–CR281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrison S, Colberg SR, Parson HK, Vinik AI. Exercise improves gait, reaction time and postural stability in older adults with type 2 diabetes and neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(5):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarenga PP, Pereira DS, Anjos DM. Functional mobility and executive function in elderly diabetics and non-diabetics. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2010;14(6):491–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito T, Sakai Y, Kubo A, et al. The relationship between physical function and postural sway during local vibratory stimulation of middle-aged people in the standing position. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26(10):1627–1630. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitney SL, Marchetti GF, Ellis J, Otis L, Asiri F, Alghadir A. Relationship between cognition and gait performance in older adults receiving physical therapy interventions in the home. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(8):1089–1098. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2012.06.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]