Abstract

Objective

Problems with clinician-patient communication negatively impact newborn screening, genetics, and all of healthcare. Training programs teach communication, but educational methods are not feasible for entire populations of clinicians. To address this healthcare quality gap, we developed a Communication Quality Assurance intervention.

Methods

Child health providers volunteered for a randomized controlled trial of assessment and a report card. Participants provided telephone counseling to a standardized parent regarding a newborn screening result showing heterozygous status for cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease. Our rapid-throughput timeline allows individualized feedback within a week. Two encounters were recorded (baseline and after a random sample received the report card) and abstracted for four groups of communication quality indicators.

Results

92 participants finished both counseling encounters within our rapid-throughput time limits. Participants randomized to receive the report card improved communication behaviors more than controls, including: request for teachback (p<0.01), opening behaviors (p=0.01), anticipate/validate emotion (p<0.001) and the ratio of explained to unexplained jargon words (p<0.03).

Conclusion

The rapid-throughput report card is effective at improving specific communication behaviors.

Practice Implications

Communication can be taught, but this project shows how healthcare organizations can assure communication quality everywhere. Further implementation could improve newborn screening, genetics, and healthcare in general.

Keywords: Communication, Professional-Patient Relations, Neonatal Screening, Quality Indicators (health care), Cystic Fibrosis, Sickle Cell Trait

1. INTRODUCTION

Communication is said to be the “main ingredient” of medical care [1]. Effective communication increases patients’ willingness to reveal information [2] and improves symptoms, adherence to recommendations, physiological measures, and biomedical outcomes [2–12]. Unfortunately, many researchers have identified problems with clinician-patient communication. Clinicians tend to interrupt patients and use jargon, and they may fail to identify patient concerns, assess understanding, address patients’ feelings, or organize their discussions [11–23]. Clinical training programs teach communication skills [2–4, 12, 13], but such skills must be reinforced to remain improved [13], and the use of expert teachers to provide feedback would be too resource-intensive for implementation over entire populations of clinicians. To fill this methodological gap, we are adapting effective techniques from Quality Improvement for the needs of communication, resulting in the approach that we call Communication Quality Assurance (Comm QA) [15–26]. For Comm QA programs to be feasible, we believe that their methods must be quantitatively reliable, standardized for trustworthy comparisons, minimally bothersome to busy clinicians, and simple enough to implement over geographic regions on a lean budget.

This project was a randomized controlled trial of an intervention that combines several Comm QA techniques for rapidly assessing, analyzing, or providing feedback about communication quality indicator scores. Feedback was conveyed by a report card, adapted from so-called “dashboard” methods used in traditional quality improvement [27].

The communication quality indicator approach is more reliable and less subjective than rating scales and checklists often used by training programs [15–22]. As with indicators in traditional quality improvement, communication quality indicators represent individual behaviors; each indicator occupies a small but important domain within the overall concept of healthcare quality [27]. Four groups of communication quality indicators were used: assessment of understanding, organizing behaviors, precautionary empathy, and jargon (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of communication quality indicators used in this project

| Quality indicator | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment of understanding group | Example [17, 18] | |

| Request for teach-back | It would be helpful to me if you could repeat back that last point in your own words. | |

| Open-ended | What questions do you have for me? | |

| Close-ended | Do you have any questions? | |

| “OK?” question* | OK? (also Alright?) | |

| Organizing behavior group | Example [23] | |

| Opening behaviors | I called you today to talk to you about your baby’s test results. | |

| Structuring behaviors | First we’ll go over what newborn screening is, and then we’ll talk about your baby’s results. | |

| Importance emphasis | The most important thing to remember is that your baby is healthy. | |

| Precautionary empathy group | Example [19] | |

| Assess for prior emotion | How have previous experiences with screening tests made you feel? | |

| Anticipate/ Validate emotion | Many people get sad when they hear this kind of news. | |

| Assess for emotion (closed) | Are you feeling sad about this news? | |

| Assess for emotion (open) | What feelings are you experiencing right now? | |

| Instruction about emotion* | Don’t worry about this. | |

| Jargon group | Description [20, 21] | |

| Total jargon words | Count of every jargon word in the transcript.** | |

| Unique jargon words | Count of jargon words used at least once in the transcript (each unique word only counted once) | |

| Jargon explanation | Any text string that explains a word or concept | |

| Jargon explanation ratio | Percentage of total jargon words that either follow an explanation of the word, or precede an explanation by two text strings (possible range, zero to 1.0) | |

Denotes a negative indicator, or a test indicator whose value for communication is unclear.

Note that a compound term (e.g. cystic fibrosis) counts as a single jargon word.

A further innovation for this project was to provide feedback within 5 business days of assessment, under the assumption that providing quantitative feedback as soon as possible would increase its effectiveness and appeal for clinicians. Methodologically this is referred to as a “rapid-throughput protocol” because data are processed through the system more quickly than can often be done for communication analyses.

We developed this project as part of our ongoing study of communication after newborn blood screening (NBS) for cystic fibrosis (CF) and sickle cell disease (SCD) [17–26]. NBS is routinely done for infants in much of the world to prevent death and disability [28]; CF is a lung and nutritional disease, while SCD is a blood disease that is associated with vascular complications and painful “crises.” Both CF and SCD are autosomal recessive conditions in which heterozygous “carrier” or “likely carrier” infants are identified by NBS in far greater numbers than infants with the actual disease. Effective communication is important for families of carrier infants because these infants are healthy but their parents can develop psychosocial problems due to misconceptions [29, 30].

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

This project was a randomized controlled trial of the effects of a rapid-throughput report card on specific communication behaviors. Physicians’ scores on a panel of communication quality indicators were measured at baseline and after a random sample received the report card intervention. We also aimed to document what response rate would follow a minimalist strategy for recruiting, since this project is the first of its kind.

The project was facilitated by a password-protected, interactive website, which allowed users to complete surveys and securely download report cards, audio recordings and transcripts. Materials and procedures were IRB approved.

2.2. Participants and recruitment

A list of 7949 physicians’ names, addresses, and characteristics was obtained from a search of the AMA Masterfile for office-based physicians in our neighboring states of Minnesota and Michigan who specialize in Family Medicine or Pediatrics. Physicians were sent two recruiting letters, one week apart. The letters briefly described the project and invited addressees to visit the website to learn more. The website detailed the project and obtained informed consent. In gratitude for time spent, participants were offered up to $60 in gift certificates.

2.3. Procedures

The project followed a rapid-throughput procedure that consisted of the 5 steps shown in Table 2. In the first step, participants completed a short entry survey on the website. The entry survey contained questions about participants’ level of experience with NBS, their confidence in explaining carrier results, and the number of patients in the participants’ clinic with SCD and CF. Randomization of survey respondents was done in blocks to reduce the effect of inadvertent trends.

Table 2.

Rapid-throughput protocol

| Timeline* | Study event |

|---|---|

| Week 1 | Recruitment, entry survey, and randomization to intervention or control |

| Week 2 | Baseline counseling task, followed by: |

| |

| Week 3 | Participants in the intervention group are e-mailed a message informing them that the report card is ready for downloading on the My-Communication website |

| Week 4 | Follow-up counseling task |

| Exit survey |

Times are approximate

The final step was an exit survey to evaluate the project experience.

2.3.1. Counseling encounters

Each participant was audiotaped in two pre-scheduled telephone calls: a “baseline encounter” and a “follow-up encounter.” The baseline encounter was done as soon after the entry survey as possible. The follow-up encounter was scheduled for approximately two weeks later.

During both encounters, a female interviewer portrayed the mother of an infant with one of two possible NBS results: SCD carrier status, or likely CF carrier status. One of the two scenarios was randomly selected for the baseline encounter, leaving the other scenario for the follow-up encounter. In the likely CF carrier scenario, the infant’s NBS result showed an elevated immunoreactive trypsinogen level and a single mutation for CF. Our research uses the term “likely CF carrier status” for this result because a sweat test is required to verify that the infant does not have CF, since 2–5% of infants with this result have an unmeasured CFTR mutation [31]. In the SCD carrier scenario the infant’s NBS result showed hemoglobin F, A, and S, which is 100% specific for carrier status. Interviewers followed our specialized protocol for standardized patient interviews, the “Brief Standardized Communication Assessment,” or BSCA [25]. In the telephone version of the BSCA, the interviewer begins by pretending to return a call: “Hello, doctor. I heard you wanted to talk with me about something?” The interviewer then allows the participant to speak for as long he or she wishes, using continuers like “uh huh” or “is there anything else I should know?” BSCA interviewers also avoid leading questions and substantial emotional reactions, in order to minimize confounds due to patient variability. Avoiding feigned, dramatic emotion also allows the evaluation of communication about the possibility of emotion (what we have called “precautionary empathy”) instead of reactions to obvious emotions [19].

Encounters were audio-recorded and transcribed without identifying words. The transcripts were parsed into individual strings of text (each of which contained one subject and one predicate), and then abstracted following the explicit-criteria procedures that we have previously demonstrated [15–23]. Abstraction was done for four groups of communication quality indicators (Table 1). For jargon explanations and the assessment of understanding group, the abstractor data dictionary provides definitions for both “definite” and “partial” designations for each behavior; the partial designation is used for suboptimal attempts at a behavior, such as assessments of understanding without a pause for response, or jargon explanations that themselves incorporate unexplained jargon. Abstractors were blind to participants’ groups and the order of the encounters.

2.3.2. Intervention

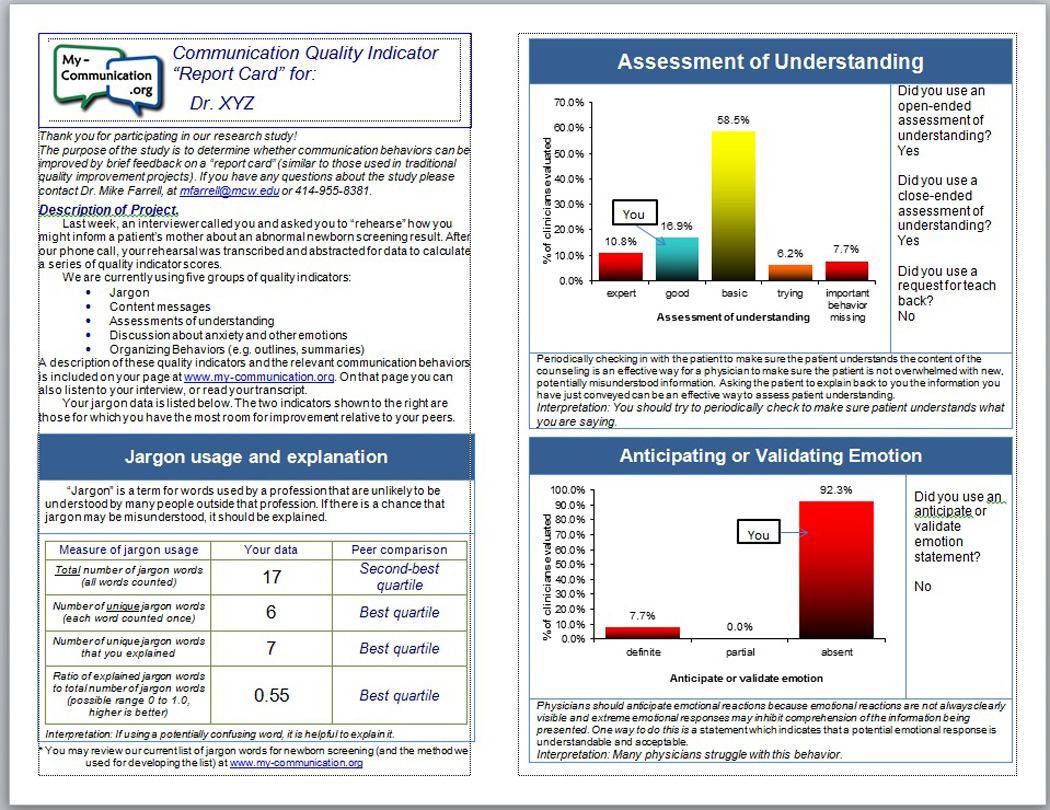

For intervention group participants, transcription was done within 1–2 days and abstraction within the 3–4 days that followed (Table 2). Within a day of the abstractions’ completion, the resulting communication quality indicator data were used to automatically generate personalized report cards (see Figure 1 for a deidentified example). Jargon data were presented with a peer-comparison by quartiles (Figure 1, lower left). Two histograms (Figure 1, upper and lower right) compared participants’ two lowest-performing indicators with peers. If a transcript had poor scores on all indicators, we gave priority to assessment of understanding and precautionary empathy, for sampling purposes and also because those behaviors are more widely described in the literature.

Figure 1.

When a histogram presented data about assessments of understanding or organizing behaviors, data were reported as either a single behavior (Figure 1, lower right) or combined several behaviors into ordinal “feedback categories” (upper right). The approach of using composite feedback categories was proposed in some of our previous reports [16, 17] as a vehicle for providing feedback that would be less esoteric than our more technical communication measures. Originally we proposed to use the letter grades A through F in our feedback scales, but for this project we decided to use the less provocative labels shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Definitions used for feedback categories

| Feedback category |

Communication quality indicator group | |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment of understanding (AUs) | Organizing behaviors | |

| Expert | Definite criteria for at least one request for teach-back | At least one usage of all three types of organizing behaviors |

| Good | Definite criteria for at least one open-ended AU | At least one opening behavior, plus either a structuring behavior or an importance emphasis |

| Basic | Definite criteria for at least one close-ended AU | At least one of a single type of organizing behavior, OR at least one structuring behavior and at least one importance emphasis but no opening behaviors |

| Trying | Definite criteria for “OK?” question, or partial criteria for another AU | No organizing behaviors apparent |

| Important behavior missing | No AUs apparent (partial criteria for “OK?” are not counted) | (not used in this project) |

When the report card was uploaded to the password-protected website, the participant was alerted by e-mail.

2.4. Analysis

Survey data were extracted from the website’s SQL database. Transcript abstraction was done with the assistance of our self-developed software application, “Transcript Abstraction System” or TAS.

Statistical procedures were done with JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and included the χ2 test, t-test, logistic regression, Spearman’s rank correlation, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test depending on variables’ characteristics. Analyses were done with an intent-to-treat approach. An a priori secondary hypothesis was tested within the intervention group to determine if indicators in a given group would be more likely to improve if feedback was specific to that group, versus feedback to some other group.

3. RESULTS

The minimalist recruiting strategy resulted in 384 (4.8%) notifications that an addressee was invalid, and 379 responses (4.8%). Of the responses, 223 (58.8%) declined to participate. The other 156 responders (41.2%) enrolled in at least part of the project, which exceeded the necessary sample size for our a priori power projections.

Likelihood of enrollment was analyzed versus data from the AMA Masterfile. Enrollment was associated with more recent graduation from medical school (O.R. 5.7, p=0.003). There were no significant differences in enrollment by gender, specialty (Family Medicine versus Pediatrics), or state (Minnesota versus Michigan).

The entry survey found that 101/156 participants (64.7%) described themselves as “very confident” or “somewhat confident” in their knowledge of CF; 114/156 (73.1%) described themselves as “very confident” or “somewhat confident” about SCD. When asked about experience, 63/156 (40.4%) claimed that they had never seen a CF carrier as a clinic patient; 33/156 (21.2%) claimed never having seen a patient with sickle cell trait.

When participants were asked about their ability to explain NBS results to a parent, 99/156 (63.5%) described themselves as “very confident” or “somewhat confident” regarding heterozygous CF results and 114/156 (73.1%) described themselves as “very confident” or “somewhat confident” regarding sickle cell trait results.

Of the 156 enrollees who completed the entry survey, 53 could not find a time within our limits to schedule the baseline encounter (34.0%). Another 11 physicians completed the baseline encounter but could not be scheduled for the follow-up encounter (7.1%). Completion did not differ significantly by participant characteristics, by whether the participants had been randomized to the intervention group, or by participants’ response to survey questions regarding their confidence or experience with NBS.

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 4 for the final sample of those physicians who completed both the baseline and follow-up encounters.

Table 4.

Characteristics of participants who completed the entire project

| n | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 51 | (55.4) |

| Female | 41 | (44.6) | |

| Years since graduation | Less than 10 | 18 | (19.6) |

| 11–20 | 32 | (34.8) | |

| 21 or more | 42 | (45.7) | |

| Specialty type | Family Medicine | 53 | (57.6) |

| Pediatrics | 35 | (38.0) | |

| Medicine-Pediatrics | 4 | (4.3) | |

| State | Michigan | 43 | (46.7) |

| Minnesota | 49 | (53.3) | |

The average duration of the encounters was 3.6 minutes (SD 1.8). Longer duration was associated with more recent graduation from medical school (rho=0.28, p=0.0001), and was greater for participants practicing in the state of Minnesota (t-test versus Michigan, p=0.0015). Duration was longer for the follow-up encounters than the baseline encounters (t-test, p=0.05). Duration was not associated with gender of the participant or NBS result discussed.

3.1. Jargon usage and explanation

Results for the jargon-related communication quality indicators are shown in Table 5. All jargon data showed considerable room for improvement, similar to our findings in previous studies [20–22]. The count of total jargon words increased from baseline to follow-up for both the intervention and control participants (Wilcoxon, each p<0.05). Total jargon was also correlated with duration of the encounter (rho=0.71, p<0.0001). The count of unique jargon words was correlated with duration (rho=0.54, p<0.0001), but there was no systematic change from baseline to follow-up for unique jargon count. This stability could reflect an unavoidability of certain jargon words in the discussions.

Table 5.

Participants’ usage of jargon and jargon explanations

| Quality indicator data | Timing | Study group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Difference for intervention group |

||||

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |||

| Unique jargon words (each word counted once) | Baseline | 7.7 | (3.6) | 8.6 | (3.8) | NS |

| Follow-up | 9.0 | (4.0) | 9.2 | (3.6) | ||

| Total number of jargon words (all words) | Baseline | 16.5 | (8.8) | 19.5 | (11.2) | NS |

| Follow-up | 22.2 | (11.5) | 25.4 | (12.0) | ||

| Jargon explanation | Baseline | 1.8 | (2.4) | 2.9 | (4.8) | NS |

| Follow-up | 3.3 | (4.3) | 5.3 | (5.8) | ||

| Jargon explanation ratio | Baseline | 0.34 | (0.43) | 0.30 | (0.27) | p<0.03 |

| Follow-up | 0.30 | (0.31) | 0.55 | (0.65) | ||

A significant improvement was seen in the jargon explanation ratio for intervention participants relative to control participants (t-test of individual differences, p<0.03). This improvement was substantial; the intervention group’s increase from 0.30 to 0.55 equates to an 83% improvement in timing. The beneficial effect of the report card persisted after adjusting for duration and whether the encounter was done at baseline or follow-up.

3.2. Assessments of understanding (AUs)

The AU data can be analyzed as individual behaviors or by transcript; comparison of these different analyses can lead to useful inferences. The top portion of Table 6 lists the AU-related results for the composite feedback categories that were given to participants on the report cards. The intervention improved participants’ feedback categories relative to the control group (χ2 test, p=0.006), with more intervention participants moving up into higher categories.

Table 6.

Change in feedback scores that were provided to participants

| Indicator | Timing | Feedback category | Control | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | n | (%) | |||

| Assessment of understanding | Baseline | Expert | 2 | (4.2) | 4 | (7.4) |

| Good | 8 | (16.7) | 9 | (16.7) | ||

| Basic | 26 | (54.2) | 35 | (64.8) | ||

| Trying | 4 | (8.3) | 3 | (5.6) | ||

| Important behavior missing | 8 | (16.7) | 3 | (5.6) | ||

|

Follow-up (p=0.006) |

Expert | 2 | (4.4) | 10 | (21.7) | |

| Good | 5 | (11.1) | 4 | (8.7) | ||

| Basic | 27 | (60.0) | 27 | (58.7) | ||

| Trying | 3 | (6.7) | 2 | (4.3) | ||

| Important behavior missing | 8 | (17.8) | 3 | (6.5) | ||

| Organizing behaviors | Baseline | Expert | 3 | (6.3) | 5 | (9.3) |

| Good | 12 | (25.0) | 16 | (30.0) | ||

| Basic | 25 | (52.1) | 24 | (44.4) | ||

| Trying | 6 | (12.5) | 7 | (13.0) | ||

| Important behavior missing | 2 | (4.2) | 2 | (3.7) | ||

|

Follow-up (NS) |

Expert | 6 | (13.3) | 6 | (13.0) | |

| Good | 11 | (24.4) | 19 | (41.3) | ||

| Basic | 16 | (35.6) | 13 | (28.3) | ||

| Trying | 8 | (17.8) | 4 | (8.7) | ||

| Important behavior missing | 4 | (8.9) | 4 | (8.7) | ||

For Table 7’s top portion the AU data were reanalyzed as the number of transcripts that contained at least one AU. This analysis confirmed a significant difference for the report card, but the increased specificity showed that the results from the feedback category analysis were driven by an increase in requests for teach-back (χ2 test, p=0.009).

Table 7.

Percent of transcripts that include at least one usage of the communication behavior

| Quality indicator data | Study group |

Total transcripts at… | Participants who acquired a new communication behavior at follow-up |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | ||||

| (% transcripts) | (% transcripts) | (% transcripts) | Signif. | ||

| Assessment of understanding | |||||

| Request for teach-back | Control | 4.1 | 4.6 | 2.3 | p<0.01 |

| Intervention | 7.4 | 21.7 | 19.6 | ||

| Open-ended | Control | 18.4 | 13.6 | 4.6 | NS |

| Intervention | 18.5 | 17.4 | 8.7 | ||

| Close-ended | Control | 67.4 | 72.7 | 11.4 | NS |

| Intervention | 88.9** | 84.8 | 4.4 | ||

| “OK?” | Control | 26.5 | 36.4 | 22.7 | NS |

| Intervention | 40.7 | 41.3 | 17.4 | ||

| Organizing behaviors | |||||

| Opening behaviors | Control | 61.2 | 50.0 | 9.1 | p=0.01 |

| Intervention | 51.9 | 63.0 | 30.8 | ||

| Structuring behaviors | Control | 12.2 | 15.9 | 11.4 | p=0.05 |

| Intervention | 13.0 | 32.6 | 28.3 | ||

| Importance emphasis | Control | 51.0 | 59.1 | 25.0 | NS |

| Intervention | 66.7 | 58.7 | 13.0 | ||

| Precautionary empathy | |||||

| Assess for prior emotion | Control | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 | NS |

| Intervention | 1.9 | 2.2 | 0.0 | ||

| Anticipate/ validate emotion |

Control | 14.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | p<0.01 |

| Intervention | 11.1 | 32.6 | 26.1 | ||

| Assess for emotion (close-ended) |

Control | 2.0 | 4.6 | 4.6 | p=0.02 |

| Intervention | 1.9 | 23.9 | 21.7 | ||

| Assess for emotion (open-ended) |

Control | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 | p=0.02 |

| Intervention | 3.7 | 23.9 | 21.7 | ||

| Instruction about emotion | Control | 26.5 | 27.3 | 18.2 | NS |

| Intervention | 22.2 | 34.8 | 26.1 | ||

Not shown (because of limited applicability): assess for possible future emotion (close-ended and open-ended) and caution about future emotion

The data in Table 8 are more detailed than the others because the unit of analysis is the individual AU behavior within each transcript, in contrast to Tables 6 and 7 where the unit of analysis is the entire transcript. This more detailed analysis confirmed the report card’s effect on requests for teach-back (Wilcoxon, p=0.02). In addition, the greater detail imparted enough power to detect a significant increase in close-ended AUs (Wilcoxon, p=0.03).

Table 8.

Mean number of individual communication behaviors per transcript

| Quality indicator data* | Study group |

Timing | Signif. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | ||||||

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | ||||

| Assessment of understanding | |||||||

| Request for teach-back | Control | 0.1 | (0.3) | 0.1 | (0.3) | p=0.02 | |

| Intervention | 0.1 | (0.4) | 0.3 | (0.6) | |||

| Open-ended | Control | 0.2 | (0.5) | 0.2 | (0.4) | NS | |

| Intervention | 0.3 | (0.7) | 0.2 | (0.5) | |||

| Close-ended | Control | 1.0 | (1.0) | 1.3 | (1.1) | p=0.03 | |

| Intervention | 2.0 | (1.5) | 2.3 | (2.1) | |||

| “OK?” | Control | 0.5 | (0.9) | 0.9 | (1.9) | NS | |

| Intervention | 0.8 | (1.8) | 0.6 | (0.9) | |||

| Organizing behaviors | |||||||

| Opening behaviors | Control | 0.8 | (0.8) | 0.7 | (0.8) | (trend, p=0.09) |

|

| Intervention | 0.7 | (0.7) | 1.0 | (1.0) | |||

| Structuring behaviors | Control | 0.14 | (0.4) | 0.5 | (1.5) | (trend, p=0.08) |

|

| Intervention | 0.2 | (0.7) | 0.9 | (1.5) | |||

| Importance emphasis | Control | 1.3 | (1.9) | 1.4 | (2.1) | NS | |

| Intervention | 1.9 | (2.3) | 1.4 | (1.6) | |||

| Precautionary empathy | |||||||

| Assess for prior emotion | Control | 0.1 | (0.3) | 0.1 | (0.3) | NS | |

| Intervention | <0.1 | (0.1) | <0.1 | (0.2) | |||

| Anticipate/ validate emotion |

Control | 0.2 | (0.5) | <0.1 | (0.3) | p<0.01 | |

| Intervention | 0.2 | (0.5) | 0.9 | (2.4) | |||

| Assess for emotion (close-ended) |

Control | <0.1 | (0.3) | <0.1 | (0.2) | p<0.01 | |

| Intervention | <0.1 | (0.3) | 0.4 | (0.8) | |||

| Assess for emotion (open-ended) |

Control | 0.1 | (0.5) | 0.1 | (0.5) | p=0.01 | |

| Intervention | 0.1 | (0.3) | 0.3 | (0.5) | |||

| Instruction about emotion | Control | 0.5 | (1.0) | 0.4 | (0.7) | NS | |

| Intervention | 0.3 | (0.6) | 0.6 | (1.0) | |||

Not shown (because of limited applicability): assess for possible future emotion (close-ended and open-ended) and caution about future emotion

3.3. Organizing behaviors

The organizing behavior data can also be analyzed as individual behaviors or by transcript. The results for composite feedback categories (Table 6, lower portion) did not differ between report card and control groups. However, when transcripts were analyzed for each organizing behavior (Table 7, middle portion), there was a significant difference in the intervention group’s use of opening behaviors (χ2 test, p=0.01) and structuring behaviors (χ2 test, p=0.05). When individual behaviors were analyzed (Table 8, middle portion), variance was high enough that significance was lost.

3.4. Subanalysis of AUs and organizing behaviors for an effect of feedback specificity

A secondary a priori hypothesis was that feedback would have a greater effect if feedback was indicator-specific, i.e., participants’ scores on a particular communication quality indicator would improve more if they were given feedback about that quality indicator, relative to participants who were only given feedback about other quality indicators.

The secondary hypothesis was supported. Most importantly, the organizing behaviors group showed a new effect: intervention participants’ scores on the feedback category were significantly higher if the report card contained feedback about organizing behaviors (Wilcoxon, p=0.02). The behavior-specific analysis showed that this new effect was driven by an increase in opening behaviors (χ2 test, p<0.02), which suggests that the effect was not simply a regression to the mean.

AUs were also increased to a greater degree when the report card contained feedback about AUs than if the report card did not contain feedback about AUs (Wilcoxon, p<0.04). Individual AU behaviors also increased more if AU-specific feedback was provided (χ2 test, p<0.02).

3.5. Precautionary empathy (communication about the potential for emotion)

We previously developed a taxonomy for up to 8 precautionary empathy behaviors [19] but for this project we only gave feedback about the “anticipate/validate emotion” behavior, to ensure that there would be enough power for our analysis. However, we also analyzed four other precautionary empathy behaviors, in order to see if feedback about one behavior influenced other types of communication about the potential for emotions.

The report card intervention lead to a greater percent of transcripts including at least one anticipate/validate emotion behavior (χ2 test, p<0.001). This finding was confirmed by analysis of the overall number of anticipate/validate emotion behaviors over the entire sample (Wilcoxon, p<0.01).

The report card also increased participants’ usage of close-ended assessments of emotion (Wilcoxon, p=0.008) and open-ended assessments of emotion (Wilcoxon, p=0.011), even though no feedback had been provided about these behaviors.

3.6. Evaluation surveys

Of 79 participants who returned the exit survey, 31 (39%) reported finding the information obtained during the project very useful, and 36 (46%) found it somewhat useful. When asked whether the rehearsal would influence future interaction with parents, 38 (48%) said it would, and 21 (27%) said it would “somewhat” influence future interactions.

Of the 42 participants who received the report card and returned an evaluation, 26 (62%) said that the report card would influence future interactions with patients, and 12 (29%) said it would “somewhat” influence future interactions.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1 Discussion

Effective communication is important for NBS, genetics, and all of healthcare. Comm QA is designed to address communication problems on a population scale, complementing educational methods that would be too labor-intensive to implement across all providers who have graduated. This randomized controlled trial showed how one particular group of Comm QA techniques improved communication quality indicator scores across two large geographic regions. The trial’s results are promising for the next step: working with a healthcare organization on a Quality Improvement program to improve communication by all of its providers. Lessons learned from the current project will provide the framework for continuing implementation of these future projects. We hope that many other types of Comm QA projects will follow.

The first lesson for Comm QA is the affirmation of our focus on communication quality indicators for assessment and feedback. Quality indicators’ quantification of individual words and phrases allows for highly detailed analyses. For example, the jargon explanation ratio allowed us to track the exact timing of explanations relative to jargon words. In a second example, the organizing behavior subanalysis showed a clear improvement when feedback was specific to that group, which argues against an artifactual effect of feedback. Finally, the impact of the report card on close-ended AUs could only be detected when individual AUs in speech were analyzed (Table 8). Such subtle differences are very useful for Comm QA because they suggest the next step for improvement. In the case of close-ended AUs the increase suggests that physicians can be influenced to assess understanding, but may lack awareness of the most effective ways to do so. This finding is similar to our previous experience [15–22], and may be similar to the results of training programs where expert grades on a 1-to-7 scale mainly tell students that they need to do better. Comm QA may be even more successful if we adopt our original goal of adding brief “how-to” materials to our assessment and feedback efforts.

Another advantage of explicit-criteria communication quality indicators is that they are objective, transparent, and replicable, which increases their acceptability and trustworthiness for busy clinicians. In contrast, Comm QA will not be feasible if annoyed physicians routinely argue about subjective ratings, as occurs when students complain after receiving a 5 instead of a 6 on a 7-item ordinal scale. Acceptability and reliability are also the reasons why we focus on individual behaviors instead of on the physicians’ global skills at communication and relationship building.

A more fundamental lesson from this project is the importance of doing Comm QA projects as an organization, just as is done for traditional QI. During our preparation for this project, some colleagues had speculated that the response rate would be high because of the value that many physicians publicly place on communication. We therefore had originally planned to compare a minimalist recruiting strategy versus a more intensive strategy that was imposed by an employer. When budget cuts led us to abandon one of the recruiting strategies we felt confident enough in our method to test its effects with a minimalist recruiting strategy. The minimalist recruiting strategy led to a low sample size, but we still had enough power to show a benefit from a simple intervention. Even so, generalizability from this project might be limited. Future versions of this project will have a greater benefit if organizations implement Comm QA projects as an institutional priority. Such a strategy would be similar to traditional Quality Improvement, in which clinicians rarely have a choice about participating.

Even if clinicians are required to participate, however, we recommend maintaining design principles from Comm QA. The report card gave peer data so the participants would know how their communication skills compared to others’. Providing transcripts of counseling encounters also gave participants an opportunity to review their own primary data. Limiting feedback to three quality indicators assured that physicians were not overwhelmed by the volume of feedback.

Another limitation is that our use of standardized patients may have seemed artificial to participants, so their quality indicator data may not generalize well to their actual practices. It could be possible to use communication quality indicators with actual patients, but the inevitable variations due to patient factors would often be perceived as unfair by physicians, and therefore unacceptable to them. On the other hand, our use of standardized patients allows physicians to be evaluated on a level playing-field. Any Hawthorne effect from simulation promotes our efforts to assess competence, which in the case of communication is more cost-effective than immediately working on performance. We therefore plan to continue using standardized patients for some projects, even as we expand to patients in actual practice for other projects.

Even as such projects may be implemented, certain limitations should be kept in mind. It is possible that the number of statistical comparisons needed for several panels of quality indicators could have increased the chances of a Type I error in the randomized controlled trial. This study did not have sufficient numbers to fully correct for a multiple-comparisons problem, but the breadth of effects in the study was encouraging. In addition, the study was not designed to examine how individual physicians used the report card. The final, dense design for the report card (Figure 1) was the result of a compromise between many different priorities and other designs used in Quality Improvement. Further study will be needed to determine whether changes in the report card’s design would increase the effectiveness of the intervention.

Further research will be necessary to tell if communication outcomes (e.g. understanding, psychological states, and satisfaction) can be improved with specific improvements in communication. Further research will also be needed before we can achieve our goal of disseminating our methods to local Quality Improvement professionals (the “project in a box” strategy). At this point therefore we would encourage interested organizations to collaborate with communication researchers who have expertise with explicit-criteria measures.

4.2 Conclusions

It is widely recognized that communication skills can be taught, but this project was designed to show how Comm QA methods can assess and improve communication long after clinicians graduate from training programs. Our rapid-throughput intervention functioned across two neighboring states, and improved jargon explanation, assessment of understanding, some organizing behaviors, and communication about the possibility of emotion.

4.3 Practice Implications

The project should be informative to future efforts to assess and improve communication in healthcare. In our view, a Comm QA approach is important because quality and performance measures are increasingly being integrated into clinician evaluations and pay-for-performance schemes. The stakes are high enough that clinicians and health organizations will want to ensure that both measures and scoring techniques are understandable and trustworthy. For NBS in particular, an effective report card mechanism aimed at improving communication quality should help insure that NBS and genetic testing lead to more benefit than harm.

Statement.

“I confirm all personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the persons described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story."

Acknowledgment

This project was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health – National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: RC1-HL100819. We are also grateful for the contributions of our transcriptionist Nadine Desmarais.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roter DL, Hall JA, editors. Doctors Talking with Patients, Patients Talking with Doctors: Improving Communication in Medical Visits. Auburn House: Westport, Connecticut; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-Patient Communication: a Review of the Literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The Impact of Patient-Centered Care on Outcomes. Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inui TS, Yourtee EL, Williamson JW. Improved outcomes in hypertension after physician tutorials. A controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1976;84:646–651. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-84-6-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27:S110–S127. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Headache Study Group of The University of Western Ontario, Predictors of outcome in headache patients presenting to family physicians--a one year prospective study. Headache. 1986;26:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egbert LD, Battit GE, Welch CE, Bartlett MK. Reduction of Postoperative Pain by Encouragement and Instruction of Patients. A Study of Doctor-Patient Rapport. N Engl J Med. 1964;270:825–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196404162701606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gittell JH, Fairfield KM, Bierbaum B, Head W, Jackson R, Kelly M, Laskin R, Lipson S, Siliski J, Thornhill T, Zuckerman J. Impact of Relational Coordination on Quality of Care, Postoperative Pain and Functioning, and Length of Stay: a Nine-Hospital Study of Surgical Patients. Medical Care. 2000;38:807–819. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, Smith DM, Kerr EA. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMatteo MR, Hays RD, Prince LM. Relationship of physicians' nonverbal communication skill to patient satisfaction, appointment noncompliance, and physician workload. Health Psychol. 1986;5:581–594. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.5.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cegala DJ, Marinelli T, Post D. The effects of patient communication skills training on compliance. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:57–64. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith R, Lyles J, Mettler J, Stoffelmayr B, Van Egeren L, Marshall A, Gardiner J, Maduschke K, Stanley J, Osborn G, Shebroe V, Greenbaum R. The effectiveness of intensive training for residents in interviewing. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:118–126. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient's agenda: have we improved? JAMA. 1999;281:283–287. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.La Pean A, Farrell MH. Initially misleading communication of carrier results after newborn genetic screening. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1499–1505. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrell MH, La Pean A, Ladouceur L. Content of communication by pediatric residents after newborn genetic screening. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1492–1498. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrell MH, Kuruvilla P. Assessment of parental understanding by pediatric residents during counseling after newborn genetic screening. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:199–204. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell MH, Kuruvilla P, Eskra KL, Christopher SA, Brienza RS. A method to quantify and compare clinicians' assessments of patient understanding during counseling of standardized patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell MH, Speiser J, Deuster L, Christopher SA. Child Health Providers’ Precautionary Discussion of Emotions during Communication about Results of Newborn Genetic Screening. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:62–67. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrell MH, Deuster L, Donovan J, Christopher SA. Pediatric residents' use of jargon during counseling about newborn genetic screening results. Pediatrics. 2008;122:243–249. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deuster L, Christopher SA, Donovan J, Farrell MH. A Method to Quantify Residents' Jargon Use During Counseling of Standardized Patients About Cancer Screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1947–1952. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0729-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrell MH, Christopher SA. Frequency of high-quality communication behaviors used by primary care providers of heterozygous infants after newborn screening. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christopher SA, Ahmad N, Bradford L, Collins J, Eskra KL, La Pean A, O'Tool F, Roedl S, Farrell MH. A method to assess the organizing behaviors used in physicians’ counseling of parents. Communication & Medicine. 2012;9:101–111. doi: 10.1558/cam.v9i2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrell MH, Christopher SA, Tluczek A, Kennedy-Parker K, La Pean A, Eskra KL, Collins J, Hoffman G, Panepinto J, Farrell P. Improving communication between doctors and parents after newborn screening. Wisconsin Medical Journal. 2011;110:221–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrell MH, Christopher SA, La Pean A, Ladouceur LK. The Brief Standardized Communication Assessment: A Patient Simulation Method Feasible for Population-Scale Use in Communication Quality Assurance. Medical Encounter. 2009;23:64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.La Pean A, Collins JL, Christopher SA, Eskra KL, Roedl SJ, Tluczek A, Farrell MH. A qualitative secondary evaluation of statewide follow-up interviews for abnormal newborn screening results for cystic fibrosis and sickle cell hemoglobinopathy. Genet Med. 2012;14:207–214. doi: 10.1038/gim.0b013e31822dd7b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mainz J. Defining and Classifying Clinical Indicators for Quality Improvement. Internat J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:523–530. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen DB, Farrell PM. Newborn screening: principles and practice. Adv Pediatr. 1996;43:231–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris H. Follow-up of children with trait in a rural setting. Pediatrics. 1989;83:876–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciske D, Haavisto A, Laxova A, Rock L, Farrell P. Genetic counseling and neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis: an assessment of the communication process. Pediatrics. 2001;107:699–705. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bobadilla JL, Farrell MH, Farrell PM. Applying CFTR molecular genetics to facilitate the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through screening. Adv Pediatr. 2002;49:131–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]