Abstract

Ladderane lipids produced by anammox bacteria constitute some of the most structurally fascinating yet poorly studied molecules among biological membrane lipids. Slow growth of the producing organism and the inherent difficulty of purifying complex lipid mixtures have prohibited isolation of useful amounts of natural ladderane lipids. We have devised a highly selective total synthesis of ladderane lipid tails and a full phosphatidylcholine to enable biophysical studies on chemically homogeneous samples of these molecules. Additionally, we report the first proof of absolute configuration of a natural ladderane.

Ladderane lipids, named for the ladder-like polycyclobutane motifs in their hydrophobic tails, are produced by anaerobic ammonium oxidizing (anammox) bacteria as a significant fraction of their membrane lipids.1 In a large intracellular compartment called the anammoxosome, anammox bacteria couple ammonium and nitrite to produce dinitrogen as their principle source of energy.2 Experimental and computational evidence suggests that ladderane lipids form a densely packed membrane around the anammoxosome and serve to limit the transmembrane diffusion of toxic or valuable metabolites from anammox catabolism.3 Ladderane lipids likely impart a number of previously unobserved characteristics in membrane settings, but their biophysical characterization has been hampered by a lack of access to pure material.3a An axenic culture of anammox bacteria is not available, and growth rates of enrichment cultures in laboratory reactors are slow (doubling times on the order of 1–2 weeks).4 Furthermore, anammox bacteria produce an array of ladderane and nonladderane lipids, which have proven inseparable on a preparative scale.3a To circumvent these difficulties, we designed a synthetic route that would allow us to access any ladderane lipid.

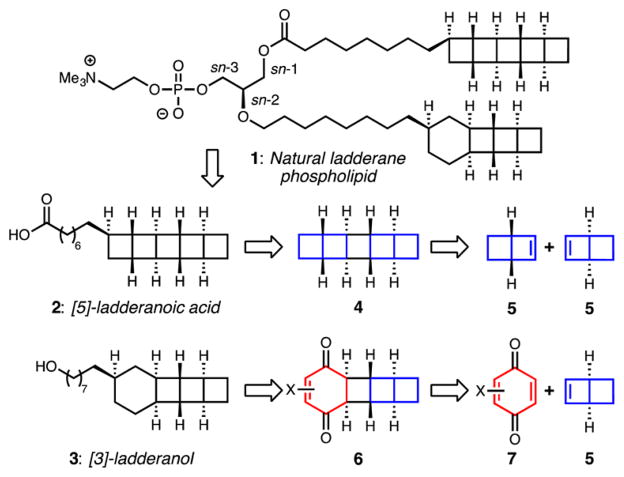

Ladderane phospholipids (e.g., 1, Scheme 1) isolated from anammox enrichment cultures comprise a mixture containing [5]-ladderane tails, as in acid 2, and [3]-ladderane tails, as in alcohol 3; the nomenclature refers to the number of cyclobutane rings at the terminus of the chain.1,5 Typically, a [3]-ladderane is attached to the central sn-2 position by an ether linkage; [5]- and [3]-ladderane lipids, as well as common straight-chain lipids, are found ether- or ester-linked at the sn-1 position. Polar head groups at the sn-3 position include phosphocholine, phosphoethanolamine, and phosphoglycerol.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis of a Natural Ladderane Phospholipid

Innovative synthetic efforts from Corey and Mascitti resulted in a racemic synthesis of [5]-ladderanoic acid (±)-2 and an enantioselective synthesis, which utilized preparative chiral stationary phase high-performance liquid chromatography to produce ~20 mg ent-2.6 No synthesis of a [3]-ladderane lipid has been reported. Despite attempts toward its elucidation, the biosynthesis of ladderanes remains unsolved.7

An outline of our retrosynthetic strategy is illustrated in Scheme 1. For both 2 and 3, we planned to install the linear alkyl component at a late stage and focused first on the polycyclic cores. We targeted the symmetric pentacycle 4, which consists of all of the cyclobutanes in the [5]-ladderane core, as a key intermediate, which we hoped to construct by dimerization of bicyclohex[2.2.0]ene 5. For [3]-ladderanol 3, retrosynthetic installation of two ketones and an alkene on the cyclohexane ring as in 6 enabled two key disconnections: a conjugate addition reaction to install the linear alkyl chain and an enoneolefin [2 + 2] photocycloaddition between a benzoquinone equivalent (7) and bicyclohexene 5.

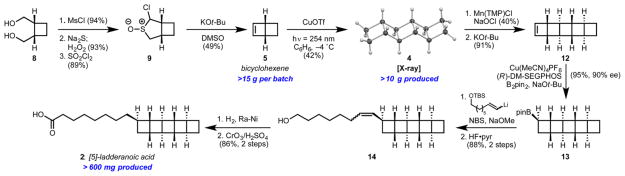

Having identified 5 as a key building block for the synthesis of both ladderane tails, we first developed a procedure to obtain this strained olefin in large quantities.8 Our optimized route commences with diol 8 (Scheme 2), which is commercially available or easily accessible from the photocycloadduct of ethylene and maleic anhydride (see Supporting Information). In three steps, we reached α-chlorosulfoxide 9 as an inconsequential mixture of diastereomers. Treatment of 9 with excess potassium tert-butoxide effected an atypical sulfoxide Ramberg–Bäcklund olefination providing, after distillation, over 15 g of 5 per batch. The use of a sulfoxide in place of the typical sulfone precursor was crucial for high yields in this transformation. The observation that the sulfoxide variant of the Ramberg–Bäcklund reaction excels in constructing strained cyclobutenes was first made by Weinges in the early 1980s, but this procedure has seen no use in synthesis.9

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of a [5]-Ladderanoic Acid

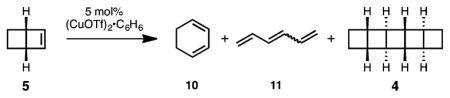

To accomplish the conversion of 5 to [5]-ladderane core 4, we hoped to employ a procedure developed by Salomon and Kochi for the dimerization of strained, but otherwise unactivated, olefins.10 Unfortunately, irradiation of THF or ether solutions of 5 with 254 nm light in the presence of catalytic copper(I) triflate (CuOTf) resulted exclusively in the formation of 1,3-cyclohexadiene (10) and a mixture of hexatriene isomers (11) (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). Encouragingly, small amounts of 4 could be observed in reactions conducted in noncoordinating heptane (entry 3). In a key discovery, we found that the electrocyclic ring opening of 5 to 10 is mediated by CuOTf even in the absence of light and that this undesired pathway could be slowed at temperatures below 0 °C (entries 4–6). Reactions performed in toluene, despite its high absorbance cutoff (284 nm), delivered 5 in an improved 28% yield (entry 7). Surprisingly, the reaction proceeds optimally in benzene, which is frozen under these conditions (entry 8).11 The [5]-ladderane pentacycle 4 can thus be obtained in 42% isolated yield. The fact that we see more than one turnover of the CuOTf catalyst seems to indicate that there is some degree of mobility in the solvent matrix. No reaction occurs in the absence of catalyst. Despite its moderate efficiency, this transformation is highly enabling: the entire pentacyclobutane core is assembled in just five steps.

Table 1.

Optimization of Bicyclohexene [2 + 2]a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | solvent | temperature | hv | 5b | 10 + 11b | 4b |

| 1 | THF | 27 °C | 254 nm | 60% | ||

| 2 | Et2O | 27 °C | 254 nm | 86% | ||

| 3 | heptane | 27 °C | 254 nm | 51% | 7% | |

| 4 | heptane | 23 °C | dark | 24% | 46%c | |

| 5 | heptane | −4 °C | dark | 70% | 2%c | |

| 6 | heptane | −4 °C | 254 nm | 43% | 39% | 18% |

| 7 | toluene | −4 °C | 254 nm | 24% | 46% | 28% |

| 8 | benzene | −4 °C | 254 nm | 21% | 37% | 42% |

Reactions were conducted on 1 mmol scale in 1 mL indicated solvent.

Yields calculated by comparison to 1H NMR internal standard.

Only 10.

Tetramesitylporphyrinatomanganese(III) chloride-catalyzed C–H chlorination according to Groves’ procedure12 was uniquely capable of functionalizing 4 and provided 40% of an intermediate chloroladderane along with 18% recovered 4. This is the first report of this chemistry on a cyclobutane. Subsequent elimination with potassium tert-butoxide delivered olefin 12 (Scheme 2). Desymmetrization of 12 was accomplished by enantioselective hydroboration with a recently disclosed copper–DM-SEGPHOS catalyst,13 which delivered pinacolboronic ester 13 in 95% yield and 90% ee. We employed a Zweifel olefination to install the 8-carbon alkyl chain.14 Following deprotection of the primary alcohol, we obtained alkene 14 in 88% yield over two steps. Hydrogenation with Ra–Ni yielded a crystalline [5]-ladderanol intermediate (X-ray: Supporting Information). Subsequent Jones oxidation completed our synthesis of the [5]-ladderanoic acid 2.

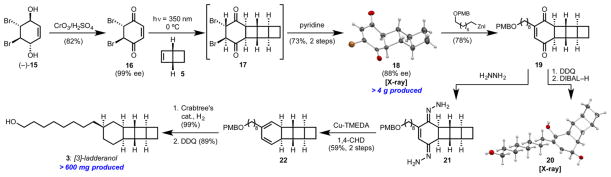

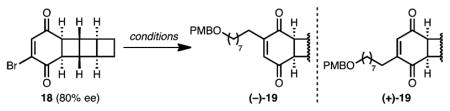

Our synthesis of [3]-ladderanol 3 (Scheme 3) centered on the use of chiral dibromobenzoquinone 16 both as a [2 + 2] partner for a high-yielding photocycloaddition with bicyclohexene 5 and as a means to relay stereochemistry into the [3]-ladderane core. Enantioenriched 16 is easily accessible from known lipase-resolved dibromodiol (–)-15 following oxidation.15 Both π faces of 16 are equivalent, and photocycloaddition with 5 from either side provides the same enantiomer of dibromodiketone 17. Upon treatment with pyridine, 17 undergoes selective elimination via proton abstraction from the convex face to form vinyl bromide 18 with slight erosion of enantiopurity. Enabled by the C2-symmetry of 16, this two-step sequence effectively achieves an enantioselective [2 + 2] cycloaddition to desymmetrized 18.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of a [3]-Ladderanol

Initial attempts to install the linear alkyl chain by Negishi cross-coupling were accompanied by significant loss of enantiopurity (80% ee 18 to +30% ee 19, Table 2, entry 1). We reasoned that two pathways might be competing: (1) palladium-catalyzed cross coupling at the site of bromine substitution and (2) uncatalyzed addition of the alkylzinc iodide reagent at the unsubstituted position, followed by elimination of HBr.16 Indeed, treatment of 18 with an alkylzinc iodide reagent in the absence of catalyst delivered 19 with inversion of the substitution pattern (entry 2). Alternatively, replacing the nucleophilic zinc reagent with a potassium trifluoroborate salt resulted in an enantioretentive Suzuki cross-coupling (entry 3). The absolute configurations of intermediates 18 and 19 (as the crystalline derivative 20, Scheme 3) were confirmed by X-ray crystallography. All that remained to elaborate 19 to a [3]-ladderane was the complete reduction of the six-membered ring. While attempting a double Wolff–Kishner reduction on bis-hydrazone 21 (Scheme 3), we discovered instead the formation of a trace amount of 1,3-cyclohexadiene 22, which arose from an apparent 2-electron oxidation and release of two molecules of dinitrogen. After extensive optimization, we arrived at commercial Cu-TMEDA as an effective oxidant and 1,4-cyclohexadiene as a hydrogen atom source for this transformation. The resulting diene 22 underwent diastereoselective hydrogenation under action of Crabtree’s catalyst. Finally, cleavage of the PMB ether completed our synthesis of [3]-ladderanol 3.

Table 2.

Enantiodivergent Coupling Strategiesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | nucleophile | catalyst | yieldb | eec |

| 1 |

|

Pd(OAc)2 + XPhos | 88% | +30% |

| 2 |

|

none | 64% | −80% |

| 3 |

|

PdCl2(dppf)•CH2Cl2 | 68% | +80% |

Reactions conducted with 80% ee 18.

Yields reflect isolated yields after silica chromatography.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral HPLC.

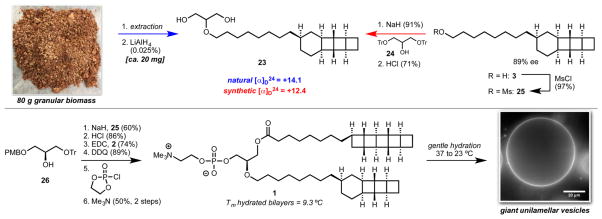

The glycerol stereocenter of ladderane phospholipids has been established to be (R), as drawn in 1, which is consistent with other prokaryotic membrane phospholipids.17 However, the absolute stereochemistry of the ladderane tails has remained unknown. With the goal of completing this assignment, we conducted a lipid extraction of biomass from an anammox enrichment culture grown over four months in a laboratory-scale bioreactor.18 Cognizant that [3]-ladderane glycerol diol 23 (Scheme 4, top) is one of the most readily separable components of ladderane lipid mixtures,1,5 we treated our crude extracts directly with lithium aluminum hydride to reduce all ester and phosphoester linkages and enrich for 23. From 80 g of dried biomass, we obtained a sufficient amount of 23 for an optical rotation ([α]D24 = +14.1). Synthetic 23 prepared via alkylation of glycerol 24 with [3]-ladderanol mesylate 25 was also found to be dextrorotatory ([α]D24 = +12.4 at 88% ee), which established the natural configuration of 23 as drawn.

Scheme 4.

Absolute Configuration of [3]-Ladderane and Synthesis of a Ladderane Phospholipid

Natural [5]-ladderane alcohol from our extracts was inseparable from the corresponding [3]-ladderane alcohol and other straight-chain lipid alcohols. To the best of our knowledge, natural [5]-ladderane, first characterized as its methyl ester, has never been completely separated from contaminating [3]-ladderane methyl ester,1,5a which makes synthesis the only way to obtain pure [5]-ladderane lipids. We have assumed by analogy to 3 that the configuration of natural 2 is as drawn (levorotatory).

More than 20 mg of natural ladderane phosphatidylcholine lipid 1 was readily prepared by a short sequence (Scheme 4, bottom). Alkylation of the enantiopure glycerol derivative 26 with mesylate 25 installed a [3]-ladderane at the sn-2 position. Removal of the trityl group and esterification with 2 installed a [5]-ladderane at the sn-1 position. Removal of the PMB group and installation of the phosphocholine headgroup completed the route to 1.

Despite the crystallinity of multiple synthetic intermediates toward 2 and 3, preliminary evidence indicates that pure 1 forms fluid hydrated bilayers at ambient temperature. Differential scanning calorimetry of aqueous dispersions of 1 revealed a single transition at 9.3 °C. Glass-supported bilayers, a common model for biological membranes, of 1 showed full fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, which indicated free lateral mobility within the bilayer (see Supporting Information). Upon gentle hydration, 1 self-assembled into giant unilamellar vesicles (Scheme 4, bottom and Supporting Information) with uniform incorporation of a fluorescently labeled lipid (0.1% Texas Red DHPE). The discovery that pure 1 self-assembles under conditions standard for natural acyclic phosphatidylcholine lipids suggests that conventional techniques can be used to probe the biophysical properties of ladderane phospholipids. Efforts to validate the hypothesis that ladderanes prevent diffusion of small anammox metabolites are underway. The synthetic route presented here will allow efficient access to a range of natural and non-natural ladderane phospholipids thus enabling full exploration of the structural and functional space around these fascinating molecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to K. V. Pedram and A. H. Valentine for experimental assistance, to Dr. A. Oliver (University of Notre Dame) and Dr. S. Teat (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories) for X-ray crystallographic analysis, to Dr. S. Lynch (Stanford University) for assistance with NMR spectroscopy, and to Prof. J. Groves (Princeton University) for helpful discussion. Prof. M. V. Martinez-Toledo (University of Granada) is acknowledged for microbiological assistance. This work was supported by Stanford University, the Terman foundation, the National Institutes of Health (GM069630 and GM118044 to SGB), the National Science Foundation (graduate fellowships to J.A.M.M., C.M.C., S.R.S., and M.D.S.), and the Center for Molecular Analysis and Design (graduate fellowship to F.R.M.).

Footnotes

ORCID

Frank R. Moss III: 0000-0002-6149-6447

Noah Z. Burns: 0000-0003-1064-4507

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b10706.

Cif files (CIF)

Cif files (CIF)

Cif files (CIF)

Cif files (CIF)

Experimental procedures, characterization, spectral data (PDF)

References

- 1.Sinninghe Damsté JS, Strous M, Rijpstra WIC, Hopmans EC, Geenevasen JAJ, van Duin ACT, van Niftrik LA, Jetten MSM. Nature. 2002;419:708–712. doi: 10.1038/nature01128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kartal B, Maalcke WJ, de Almeida NM, Cirpus I, Gloerich J, Geerts W, Op den Camp HJM, Harhangi HR, Janssen-Megens EM, Francoijs K-J, Stunnenberg JT, Keltjens JT, Jetten MSM, Strous M. Nature. 2011;479:127–130. doi: 10.1038/nature10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuenen JG. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:320–326. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kartal B, de Almeida NM, Maalcke WJ, Op den Camp HJM, Jetten MSM, Keltjens JT. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:428–461. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Boumann HA, Longo ML, Stroeve P, Poolman B, Hopmans EC, Stuart MCA, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Schouten S. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2009;1788:1444–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boumann HA, Stroeve P, Longo ML, Poolman B, Kuiper JM, Hopmans EC, Jetten MSM, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Schouten S. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2009;1788:1452–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Niftrik LA, Fuerst JA, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Kuenen JG, Jetten MSM, Strous M. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;233:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wagner JP, Schreiner PR. J Chem Theory Comput. 2014;10:1353–1358. doi: 10.1021/ct5000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chaban VC, Nielsen MB, Kopec W, Khandelia H. Chem Phys Lipids. 2014;181:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nouri DH, Tantillo DJ. Curr Org Chem. 2006;10:2055–2075. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Strous M, Heijnen JJ, Kuenen JG, Jetten MSM. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;50:589–596. [Google Scholar]; (b) van der Star WRL, Miclea AI, van Dongen UGJM, Muyzer G, Picioreanu C, van Loosdrecht MCM. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;101:286–294. doi: 10.1002/bit.21891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Sinninghe Damsté JS, Rijpstra WIC, Geenevasen JAJ, Strous M, Jetten MSM. FEBS J. 2005;272:4270–4283. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boumann HA, Hopmans EC, van de Leemput I, Op den Camp HJM, van de Vossenberg J, Strous M, Jetten MSM, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Schouten S. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rattray JE, van de Vossenberg J, Hopmans EC, Kartal B, van Niftrik L, Rijpstra WIC, Strous M, Jetten MSM, Schouten S, Sinninghe Damsté JS. Arch Microbiol. 2008;190:51–66. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0364-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Mascitti V, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15664–15665. doi: 10.1021/ja044089a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mascitti V, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3118–3119. doi: 10.1021/ja058370g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Rattray JE, Strous M, Op den Camp HJM, Schouten S, Jetten MSM, Sinninghe Damsté JS. Biol Direct. 2009;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Javidpour P, Deutsch S, Mutalik VK, Hillson NJ, Petzold CJ, Keasling JD, Beller HR. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An existing route to 5, though expeditious, was deemed ill-suited for scales larger than 1 gram: McDonald RN, Reineke CE. J Org Chem. 1967;32:1878–1887.

- 9.Weinges K, Sipos W, Klein J, Deuter J, Irngartinger H. Chem Ber. 1987;120:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salomon RG, Kochi JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:1137–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efficient photochemical reactions in frozen solvent have been documented: Beukers R, Berends W. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1960;41:550–551. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90063-9.Beukers R, Berends W. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961;49:181–189.Kaláb D. Experientia. 1966;22:23–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01897746.

- 12.Liu W, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12847–12849. doi: 10.1021/ja105548x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guisán-Ceinos M, Parra A, Martín-Heras V, Tortosa M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:6969–6972. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zweifel G, Fisher RP, Snow TJ, Whitney CC. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:6309–6311.Evans DA, Thomas RC, Walker JA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976;17:1427–1430.(c) Use of N-bromosuccinimide as opposed to other halonium sources was critical for high efficiencies in this coupling.

- 15.Sanfilippo C, Patti A, Nicolosi G. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2000;11:1043–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bromonaphthoquinones are known to be more electrophilic at the unsubstituted site: Gruenwell JR, Karipides A, Wigal CT, Heinzman SW, Parlow J, Surso JA, Clayton L, Fleitz FJ, Daffner M, Stevens JE. J Org Chem. 1991;56:91–95.

- 17.Sinninghe Damsté JS, Rijpstra WIC, Strous M, Jetten MSM, David ORP, Geenevasen JAJ, van Maarseveen JH. Chem Commun. 2004:2590–2591. doi: 10.1039/b409806d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez-Martinez A, Rodriguez-Sanchez A, Garcia-Ruiz MJ, Muñoz-Palazon B, Cortes-Lorenzo C, Osorio F, Vahala R. Chem Eng J. 2016;287:557–567. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.