Abstract

Differences in kidney transplantation outcomes across GN subtypes have rarely been studied. From the US Renal Data System, we identified all adult (≥18 years) first kidney transplant recipients (1996–2011) with ESRD attributed to one of six GN subtypes or two comparator kidney diseases. We computed hazard ratios (HRs) for death, all-cause allograft failure, and allograft failure excluding death as a cause (competing risks framework) using Cox proportional hazards regression. Among the 32,131 patients with GN studied, patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN) had the lowest mortality rates and patients with IgAN or vasculitis had the lowest allograft failure rates. After adjusting for patient- and transplant-related factors, compared with IgAN (referent), FSGS, membranous nephropathy, membranoproliferative GN, lupus nephritis, and vasculitis associated with HRs (95% confidence intervals) for death of 1.57 (1.43 to 1.72), 1.52 (1.34 to 1.72), 1.76 (1.55 to 2.01), 1.82 (1.63 to 2.02), and 1.56 (1.34 to 1.81), respectively, and with HRs for allograft failure excluding death as a cause of 1.20 (1.12 to 1.28), 1.27 (1.14 to 1.41), 1.50 (1.36 to 1.66), 1.11 (1.02 to 1.20), and 0.94 (0.81 to 1.09), respectively. Considering external comparator groups, and comparing with IgAN, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and diabetic nephropathy associated with higher HRs for mortality [1.22 (1.12 to 1.34) and 2.57 (2.35 to 2.82), respectively], but ADPKD associated with a lower HR for allograft failure excluding death as a cause [0.85 (0.79 to 0.91)]. Reasons for differential outcomes by GN subtype and cause of ESRD should be examined in future research.

Keywords: glomerulonephritis, kidney transplantation, chronic allograft failure, mortality, clinical epidemiology

Kidney transplantation, as compared with dialysis, offers improved longevity1,2 and quality of life3 in patients with ESRD. However, transplanted allografts do not function indefinitely and, after 10 years, almost half of all kidney transplant recipients will have died, resumed dialysis, or undergone repeat kidney transplantation.4 Indeed, long-term allograft survival has improved little in recent decades,5 and mortality in transplant recipients remains up to four-fold higher than in persons without ESRD.6 Understanding the relative contributions to allograft failure from death and from nonfatal causes is key to prioritizing interventional strategies aimed at maximizing patient and allograft outcomes.

In patients with ESRD due to GN, research in the transplant field has often focused on identifying, preventing, or treating GN recurrence in the transplanted kidney.7–12 By comparison, much less is known regarding absolute and relative risks for death and for other causes of allograft failure among individual GN subtypes. A recent study compared rates of patient and allograft survival across four primary GN subtypes in a European patient cohort.13 However, a similar study has not been conducted at the United States population level, nor have comparisons between primary and secondary GN subtypes, or exploration of shorter-term outcomes, been performed.

We therefore examined differences in patient and allograft survival after kidney transplantation among patients with ESRD attributed to any of six selected GN subtypes who received a first kidney transplant in the United States between 1996 and 2011. As external comparator groups, we also evaluated outcomes in patients with ESRD due to diabetic nephropathy or autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Using a competing risks approach, we aimed to determine absolute and relative rates of death and of allograft failure (including or excluding death as a cause) for each of these causes of ESRD. We also examined cause of death, cause of allograft failure, and early post-transplant complications as secondary outcomes.

Results

Patient Characteristics

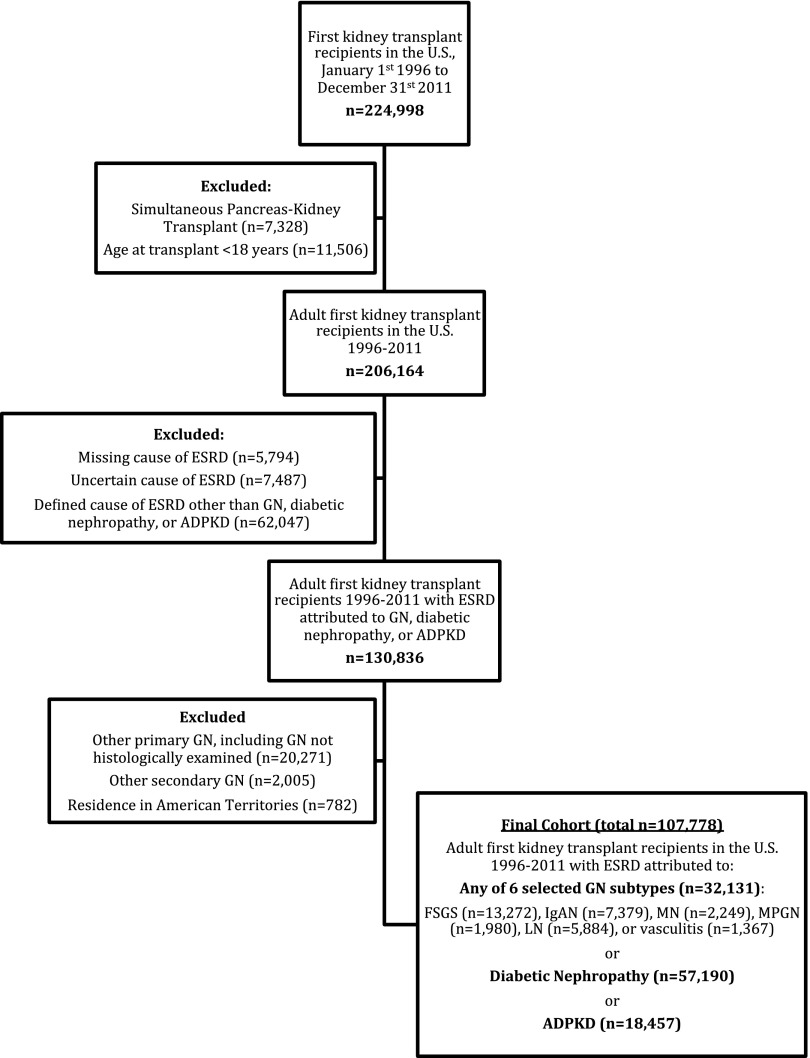

The study cohort was assembled as summarized in Figure 1. Among the 107,778 patients studied, 32,131 had ESRD attributed to one of the six selected GN subtypes. Baseline demographic, socioeconomic, comorbidity, and transplant-related characteristics differed considerably by cause of ESRD (Table 1). Among the GN subtypes, average age at transplant ranged from 38 years in LN to 49 years in membranous nephropathy (MN) or vasculitis; the proportion of men ranged from 19% in lupus nephritis (LN) to 69% in MN; and the percentage of patients with black race ranged from 5% in IgA nephropathy (IgAN) to 40% in LN. Patients with IgAN were most likely to have private insurance (61% versus 37%–46%) and to have completed a college education (48% versus 38%–45%). Comorbidities were generally least frequent in patients with IgAN and most frequent in patients with MN. Prior Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was most frequent in membranoproliferative GN (MPGN) (10% versus 2%–5%). Patients with IgAN had the shortest dialysis duration (vintage) before transplantation, and were most likely to have received a pre-emptive (21%) or living donor (58%) transplant. Patients with LN were most highly sensitized to human leukocyte antigens. When compared with patients with any of the GN subtypes, patients with diabetic nephropathy had a higher cardiovascular and cerebrovascular comorbidity burden. Patients with ADPKD were most comparable to those with IgAN, in terms of having a high frequency of pre-emptive kidney transplants, private insurance, and college education, although they received less living donor transplants.

Figure 1.

Assembly of the final study cohort of patients with ESRD due to GN, diabetic nephropathy, or autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD).

Table 1.

Patient and donor characteristics at time of kidney transplantation, by cause of ESRD, among United States adult kidney transplant recipients with ESRD due to GN, DN, or ADPKD, 1996–2011 (n=107,778)

| Characteristics | Primary GN Subtypes | Secondary GN Subtypes | Non-GN Comparator Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSGS | IgAN | MN | MPGN | LN | Vasculitis | DN | ADPKD | |

| n=13,272 | n=7379 | n=2249 | n=1980 | n=5884 | n=1367 | n=57,190 | n=18,457 | |

| Age, yr | ||||||||

| Mean, SD | 43.9 (14.1) | 41.6 (12.6) | 49.3 (13.2) | 43.2 (14.4) | 38.3 (11.5) | 48.8 (15.1) | 52.3 (11.5) | 52.2 (9.5) |

| <40 | 5307 (40) | 3457 (46.8) | 523 (23.3) | 804 (40.6) | 3289 (55.9) | 366 (26.8) | 9285 (16.2) | 1535 (8.3) |

| 40–59 | 5933 (44.7) | 3223 (43.7) | 1164 (51.8) | 885 (44.7) | 2323 (39.5) | 618 (45.2) | 30,654 (53.6) | 12,864 (69.7) |

| 60–69 | 1621 (12.2) | 578 (7.8) | 467 (20.8) | 258 (13) | 246 (4.2) | 294 (21.5) | 14,702 (25.7) | 3403 (18.4) |

| 70+ | 411 (3.1) | 121 (1.6) | 95 (4.2) | 33 (1.7) | 26 (0.4) | 89 (6.5) | 2549 (4.5) | 655 (3.5) |

| Male sex | 8225 (62) | 5003 (67.8) | 1553 (69.1) | 1181 (59.6) | 1102 (18.7) | 752 (55) | 36,169 (63.2) | 10,081 (54.6) |

| Racea | ||||||||

| White | 7902 (59.5) | 5580 (75.6) | 1609 (71.5) | 1537 (77.6) | 2989 (50.8) | 1197 (87.6) | 39,530 (69.1) | 15,857 (85.9) |

| Black | 4575 (34.5) | 392 (5.3) | 512 (22.8) | 269 (13.6) | 2360 (40.1) | 97 (7.1) | 13,440 (23.5) | 1635 (8.9) |

| Asian | 585 (4.4) | 1219 (16.5) | 94 (4.2) | 137 (6.9) | 436 (7.4) | 54 (4) | 2629 (4.6) | 818 (4.4) |

| Other | 209 (1.6) | 188 (2.5) | 33 (1.5) | 37 (1.9) | 98 (1.7) | 19 (1.4) | 1584 (2.8) | 147 (0.8) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1246 (9.4) | 810 (11) | 244 (10.8) | 211 (10.7) | 969 (16.5) | 127 (9.3) | 8301 (14.5) | 1202 (6.5) |

| Missing | 384 (2.9) | 123 (1.7) | 46 (2.0) | 83 (4.2) | 187 (3.2) | 22 (1.6) | 3928 (6.9) | 1320 (7.2) |

| Geographic region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 2770 (20.9) | 1398 (18.9) | 514 (22.9) | 427 (21.6) | 1161 (19.7) | 272 (19.9) | 10,967 (19.2) | 3831 (20.8) |

| Midwest | 3166 (23.9) | 1838 (24.9) | 545 (24.2) | 527 (26.6) | 1154 (19.6) | 414 (30.3) | 14,289 (25.0) | 4578 (24.8) |

| South | 5155 (38.8) | 2177 (29.5) | 800 (35.6) | 650 (32.8) | 2252 (38.3) | 397 (29.0) | 19,887 (34.8) | 6283 (34) |

| West | 2181 (16.4) | 1966 (26.6) | 390 (17.3) | 376 (19) | 1317 (22.4) | 284 (20.8) | 12,047 (21.1) | 3765 (20.4) |

| Dialysis modality before transplantation | ||||||||

| None (pre-emptive) | 2080 (15.7) | 1540 (20.9) | 301 (13.4) | 326 (16.5) | 500 (8.5) | 122 (8.9) | 5459 (9.5) | 4562 (24.7) |

| Hemodialysis | 8397 (63.3) | 4049 (54.9) | 1467 (65.2) | 1216 (61.4) | 4174 (70.9) | 978 (71.5) | 42,267 (73.9) | 10,279 (55.7) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 2350 (17.7) | 1400 (19) | 405 (18) | 358 (18.1) | 1071 (18.2) | 233 (17) | 7884 (13.8) | 2731 (14.8) |

| Missing | 445 (3.4) | 390 (5.3) | 76 (3.4) | 80 (4) | 139 (2.4) | 34 (2.5) | 1580 (2.8) | 885 (4.8) |

| Dialysis duration (vintage) before transplantation | ||||||||

| Median (IQR), d | 590 (162–1317) | 322 (48–911) | 600 (197–1285) | 506 (128–1148) | 929 (348–1730) | 697 (326–1326) | 703 (295–1307) | 407 (1–1030) |

| None (pre-emptive) | 2080 (15.7) | 1540 (20.9) | 301 (13.4) | 326 (16.5) | 500 (8.5) | 122 (8.9) | 5459 (9.5) | 4562 (24.7) |

| <1 yr | 2919 (22) | 2374 (32.2) | 524 (23.3) | 500 (25.3) | 1027 (17.5) | 250 (18.3) | 11,502 (20.1) | 4274 (23.2) |

| 1–3 yr | 4094 (30.8) | 1991 (27) | 741 (32.9) | 624 (31.5) | 1784 (30.3) | 546 (39.9) | 21,923 (38.3) | 5394 (29.2) |

| 3–5 yr | 2348 (17.7) | 946 (12.8) | 408 (18.1) | 289 (14.6) | 1222 (20.8) | 272 (19.9) | 11,417 (20.0) | 2602 (14.1) |

| >5 yr | 1831 (13.8) | 528 (7.2) | 275 (12.2) | 241 (12.2) | 1351 (23) | 177 (12.9) | 6889 (12.0) | 1625 (8.8) |

| Completed college | 5661 (42.7) | 3573 (48.4) | 860 (38.2) | 800 (40.4) | 2627 (44.6) | 573 (41.9) | 21,404 (37.4) | 8838 (47.9) |

| Missing | 2221 (16.7) | 1207 (16.4) | 410 (18.2) | 378 (19.1) | 1036 (17.6) | 222 (16.2) | 10,717 (18.7) | 3178 (17.2) |

| Insurance payer at transplanta | ||||||||

| Private | 6132 (46.2) | 4476 (60.7) | 1003 (44.6) | 919 (46.4) | 2172 (36.9) | 583 (42.6) | 22,066 (38.6) | 10,776 (58.4) |

| Medicaid | 575 (4.3) | 243 (3.3) | 86 (3.8) | 104 (5.3) | 349 (5.9) | 29 (2.1) | 2298 (4.0) | 369 (2.0) |

| Medicare | 6203 (46.7) | 2496 (33.8) | 1113 (49.5) | 900 (45.5) | 3244 (55.1) | 741 (54.2) | 31,657 (55.4) | 6905 (37.4) |

| Veterans Affairs | 85 (0.6) | 44 (0.6) | 16 (0.7) | 14 (0.7) | 11 (0.2) | 7 (0.5) | 355 (0.6) | 94 (0.5) |

| Other | 233 (1.8) | 98 (1.3) | 24 (1.1) | 27 (1.4) | 79 (1.3) | 6 (0.4) | 549 (1.0) | 248 (1.3) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Diabetes | 857 (6.5) | 273 (3.7) | 169 (7.5) | 125 (6.3) | 254 (4.3) | 90 (6.6) | 46,253 (80.9) | 760 (4.1) |

| Heart failure | 596 (4.5) | 220 (3) | 166 (7.4) | 107 (5.4) | 444 (7.5) | 66 (4.8) | 9607 (16.8) | 416 (2.3) |

| Coronary heart disease | 572 (4.3) | 181 (2.5) | 142 (6.3) | 72 (3.6) | 173 (2.9) | 54 (4.0) | 8256 (14.4) | 822 (4.5) |

| CVA/TIA | 165 (1.2) | 69 (0.9) | 31 (1.4) | 17 (0.9) | 163 (2.8) | 31 (2.3) | 2327 (4.1) | 350 (1.9) |

| Hypertension | 9526 (71.8) | 5729 (77.6) | 1602 (71.2) | 1374 (69.4) | 3937 (66.9) | 851 (62.3) | 42,519 (74.3) | 13,749 (74.5) |

| COPD | 206 (1.6) | 47 (0.6) | 47 (2.1) | 27 (1.4) | 30 (0.5) | 33 (2.4) | 934 (1.6) | 178 (1.0) |

| Current/recent smoker | 569 (4.3) | 212 (2.9) | 126 (5.6) | 90 (4.5) | 142 (2.4) | 37 (2.7) | 1931 (3.4) | 559 (3) |

| Cancer | 244 (1.8) | 74 (1) | 52 (2.3) | 45 (2.3) | 39 (0.7) | 29 (2.1) | 730 (1.3) | 310 (1.7) |

| PVD | 188 (1.4) | 59 (0.8) | 49 (2.2) | 29 (1.5) | 87 (1.5) | 29 (2.1) | 5885 (10.3) | 173 (0.9) |

| Nonambulant | 35 (0.3) | 10 (0.1) | <10 (<1.0) | <10 (<1.0) | 40 (0.7) | <10 (<1.0) | 365 (0.6) | 26 (0.1) |

| Missing | 568 (4.3) | 72 (1.0) | 121(5.4) | 95 (4.8) | 345 (6.2) | 49 (3.6) | 2551 (4.5) | 934(5.1) |

| HCV positive at transplant | 629 (4.7) | 122 (1.7) | 65 (2.9) | 197 (10.0) | 137 (2.3) | 25 (1.8) | 2815(4.9) | 403(2.2) |

| Missing | 1166 (8.8) | 591 (8.0) | 217 (9.7) | 192 (9.7) | 544 (8.0) | 128 (9.4) | 4918 (8.6) | 1598 (8.7) |

| BMI at transplant, kg/m2 | ||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 27.4 (23.6–31.8) | 26.3 (23.0–30.1) | 26.6 (23.6–30.6) | 24.9 (22.0–28.9) | 23.8 (21.0–27.8) | 25.7 (22.4–29.8) | 27.5 (24.1–31.6) | 26.5 (23.5–30.2) |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 352 (2.7) | 189 (2.6) | 28 (1.2) | 72 (3.6) | 360 (6.1) | 46 (3.4) | 727 (1.3) | 320 (1.7) |

| Normal (18.5–25) | 3627 (27.3) | 2535 (34.4) | 671 (29.8) | 774 (39.1) | 2600 (44.2) | 503 (36.8) | 14,287 (25.0) | 5818 (31.5) |

| Overweight (25–30) | 3834 (28.9) | 2217 (30) | 732 (32.5) | 506 (25.6) | 1389 (23.6) | 396 (29) | 17,375 (30.4) | 6063 (32.8) |

| Obese (>30) | 4044 (30.5) | 1761 (23.9) | 567 (25.2) | 371 (18.7) | 840 (14.3) | 312 (22.8) | 18,406 (32.2) | 4332 (23.5) |

| Missing | 1415 (10.7) | 677 (9.2) | 251 (11.2) | 257 (13) | 695 (11.8) | 110 (8) | 6395 (11.2) | 1924 (10.4) |

| Prior blood transfusion | 2246 (16.9) | 1092 (14.8) | 420 (18.7) | 427 (21.6) | 1918 (32.6) | 474 (34.7) | 13,206 (23.1) | 2764 (15.0) |

| Missing | 1783 (13.4) | 846 (11.5) | 350 (15.6) | 297 (15) | 843 (14.3) | 150 (11) | 7855 (13.7) | 2457 (13.3) |

| Recipient blood groupa | ||||||||

| O | 5901 (44.5) | 3311 (44.9) | 1020 (45.4) | 881 (44.5) | 2849 (48.4) | 617 (45.1) | 24,659 (43.1) | 8210 (44.5) |

| A | 4847 (36.5) | 2769 (37.5) | 818 (36.4) | 738 (37.3) | 1909 (32.4) | 563 (41.2) | 22,275 (38.9) | 7357 (39.9) |

| B | 1877 (14.1) | 941 (12.8) | 305 (13.6) | 253 (12.8) | 858 (14.6) | 132 (9.7) | 7109 (12.4) | 2035 (11.0) |

| AB | 614 (4.6) | 339 (4.6) | 103 (4.6) | 97 (4.9) | 246 (4.2) | 55 (4) | 2912 (5.1) | 821 (4.4) |

| Anti-HLA sensitization | ||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–8) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–8) | 0 (0–10) | 5 (0–44) | 0 (0–10) | 0 (0–7) | 0 (0–19) |

| Low (PPRA<10%) | 8294 (62.5) | 4370 (59.2) | 1375 (61.1) | 1136 (57.4) | 2615 (44.4) | 794 (58.1) | 33,287 (58.2) | 11,435 (62.0) |

| Moderate (PPRA 10%–80%) | 1765 (13.3) | 737 (10) | 296 (13.2) | 266 (13.4) | 1405 (23.9) | 197 (14.4) | 6986 (12.2) | 2705 (14.7) |

| High (PPRA >80%) | 482 (3.6) | 180 (2.4) | 79 (3.5) | 88 (4.4) | 630 (10.7) | 54 (4) | 1905 (3.3) | 695 (3.8) |

| Missing | 2731 (20.6) | 2092 (28.4) | 499 (22.2) | 490 (24.7) | 1234 (21) | 322 (23.6) | 15,012 (26.2) | 3622 (19.6) |

| HLA mismatch | ||||||||

| 0 mismatch | 1387 (10.5) | 909 (12.3) | 271 (12) | 263 (13.3) | 749 (12.7) | 177 (12.9) | 6063 (10.6) | 2053 (11.1) |

| 1–3 mismatch | 4619 (34.8) | 2848 (38.6) | 819 (36.4) | 737 (37.2) | 2035 (34.6) | 547 (40) | 17,986 (31.4) | 5752 (31.2) |

| 4–6 mismatch | 7017 (52.9) | 3473 (47.1) | 1128 (50.2) | 915 (46.2) | 2971 (50.5) | 626 (45.8) | 31,875 (55.7) | 10,334 (56.0) |

| Missing | 249 (1.9) | 149 (2) | 31 (1.4) | 65 (3.3) | 129 (2.2) | 17 (1.2) | 1266 (2.2) | 318 (1.7) |

| Type of transplant | ||||||||

| Living | 5692 (42.9) | 4306 (58.4) | 982 (43.7) | 878 (44.3) | 2594 (44.1) | 685 (50.1) | 17,934 (31.4) | 7748 (42.0) |

| Standard deceased | 6060 (45.7) | 2502 (33.9) | 957 (42.6) | 864 (43.6) | 2721 (46.2) | 534 (39.1) | 29,034 (50.8) | 8179 (44.3) |

| Expanded criteria | 955 (7.2) | 336 (4.6) | 218 (9.7) | 134 (6.8) | 305 (5.2) | 103 (7.5) | 7023 (12.3) | 1662 (9.0) |

| Missing | 565 (4.3) | 235 (3.2) | 92 (4.1) | 104 (5.3) | 264 (4.5) | 45 (3.3) | 3199 (5.6) | 868 (4.7) |

| Cold ischemia time | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.2 (11.5) | 7.1 (10.5) | 10.2 (11.4) | 10.0 (11.5) | 10.0 (11.7) | 8.7 (10.9) | 12.1 (11.2) | 10.4 (11.4) |

| <12 h | 7237 (54.5) | 4979 (67.5) | 1217 (54.1) | 1106 (55.9) | 3264 (55.5) | 827 (60.5) | 26,495 (46.3) | 9841 (53.3) |

| 12–24 h | 3684 (27.8) | 1500 (20.3) | 618 (27.5) | 508 (25.7) | 1563 (26.6) | 329 (24.1) | 18,841 (32.9) | 5179 (28.1) |

| >24 h | 1738 (13.1) | 632 (8.6) | 305 (13.6) | 259 (13.1) | 762 (13) | 153 (11.2) | 8318 (14.5) | 2484 (13.5) |

| Missing | 613 (4.6) | 268 (3.6) | 109 (4.8) | 107 (5.4) | 295 (5) | 58 (4.2) | 3536 (6.2) | 953 (5.2) |

| Donor age, yr | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.1 (14.5) | 38.3 (13.8) | 39.8 (14.4) | 38.0 (14.5) | 36.7 (14.6) | 39.8 (14.5) | 39.1 (15.4) | 40.6 (14.8) |

| Missing | 569 (4.3) | 236 (3.2) | 93 (4.1) | 105 (5.3) | 270 (4.6) | 46 (3.4) | 3208 (5.6) | 870 (4.7) |

| Donor male sexa | 6791 (51.2) | 3598 (48.8) | 1144 (50.9) | 1018 (51.4) | 3137 (53.3) | 667 (48.8) | 30,129 (52.7) | 9275 (50.3) |

| Donor racea | ||||||||

| White | 9760 (73.5) | 5818 (78.8) | 1766 (78.5) | 1601 (80.9) | 3912 (66.5) | 1154 (84.4) | 44,008 (77.0) | 15,758 (85.4) |

| Black | 2238 (16.9) | 423 (5.7) | 273 (12.1) | 183 (9.2) | 1164 (19.8) | 97 (7.1) | 7076 (12.4) | 1399 (7.6) |

| Asian | 275 (2.1) | 436 (5.9) | 35 (1.6) | 54 (2.7) | 196 (3.3) | 14 (1) | 1223 (2.1) | 270 (1.5) |

| Other | 953 (7.2) | 681 (9.2) | 171 (7.6) | 127 (6.4) | 584 (9.9) | 102 (7.5) | 4624 (8.1) | 973 (5.3) |

| Initial immunosuppression | ||||||||

| Alemtuzumab | 1007 (7.6) | 551 (7.5) | 162 (7.2) | 128 (6.5) | 356 (6.1) | 104 (7.6) | 3721 (6.5) | 1319 (7.1) |

| Basiliximab | 2563 (19.3) | 1535 (20.8) | 461 (20.5) | 384 (19.4) | 1062 (18) | 272 (19.9) | 10,892 (19.0) | 3684 (20.0) |

| Daclizumab | 1295 (9.8) | 746 (10.1) | 220 (9.8) | 212 (10.7) | 588 (10) | 127 (9.3) | 5598 (9.8) | 1607 (8.7) |

| Thymoglobulin | 4976 (37.5) | 2552 (34.6) | 791 (35.2) | 652 (32.9) | 2304 (39.2) | 489 (35.8) | 19,698 (34.4) | 6407 (34.7) |

| Tacrolimus | 9128 (68.8) | 5172 (70.1) | 1491 (66.3) | 1322 (66.8) | 4193 (71.3) | 932 (68.2) | 38,088 (66.6) | 12,161 (65.9) |

| Ciclosporin | 3763 (28.4) | 2099 (28.4) | 677 (30.1) | 628 (31.7) | 1543 (26.2) | 363 (26.6) | 16,123 (28.2) | 5452 (29.5) |

| Sirolimus | 1089 (8.2) | 583 (7.9) | 204 (9.1) | 156 (7.9) | 427 (7.3) | 114 (8.3) | 4446 (7.8) | 1486 (8.1) |

| Mycophenolate | 11313 (85.2) | 6376 (86.4) | 1885 (83.8) | 1692 (85.5) | 5008 (85.1) | 1135 (83) | 47,861 (83.7) | 15,459 (83.8) |

| Azathioprine | 631 (4.8) | 356 (4.8) | 143 (6.4) | 133 (6.7) | 309 (5.3) | 79 (5.8) | 3482 (6.1) | 1090 (5.9) |

| Steroid | 12561 (94.6) | 6980 (94.6) | 2108 (93.7) | 1877 (94.8) | 5634 (95.8) | 1300 (95.1) | 53,919 (94.3) | 17,400 (94.3) |

| Missing | 186 (1.4) | 68 (0.9) | 30 (1.3) | 23 (1.2) | 83 (1.4) | 14 (1.0) | 964 (1.7) | 251 (1.4) |

| DGF | 2032 (15.3) | 662 (9.0) | 329 (14.6) | 267 (13.5) | 751 (12.8) | 163 (11.9) | 11,222 (17.6) | 2230 (12.1) |

| Missing DGF | 57 (0.4) | 31 (0.4) | 13 (0.6) | 21 (1.1) | 37 (0.6) | <10 (<0.5) | 6993 (10.9) | 75 (0.4) |

All values represent n (%) except where otherwise stated. DN, diabetic nephropathy; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; BMI, body mass index; HLA, human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen; PPRA, peak panel reactive antibody.

Missing n<1% for all GN subtypes.

Patient Survival

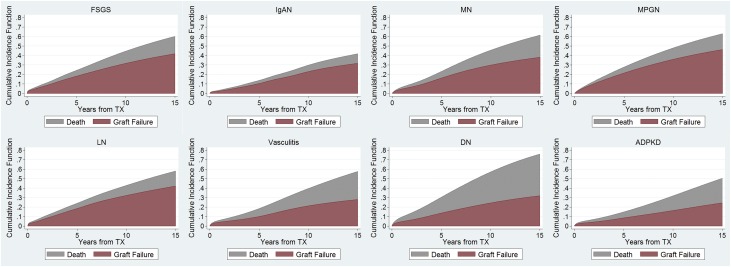

After a median follow-up of 5.5 (interquartile range [IQR], 2.6–9.3) years, 28,319 (26.3%) patients died. Among the GN subtypes, mortality was lowest in IgAN (1.2 deaths per 100 person years) and highest in vasculitis (3.2 deaths per 100 person years). Compared with the GN subtypes, mortality was substantially higher in diabetic nephropathy (6.2 deaths per 100 person years), but was midway between that of IgAN and vasculitis for ADPKD (2.4 deaths per 100 patient years) (Figure 2, Table 2). Among the GN subtypes, 5-, 10-, and 15-year cumulative incidences of death with a functioning allograft were also lowest in IgAN (3%, 7%, and 10%, respectively) and highest in vasculitis (9%, 18%, and 30%, respectively) (Supplemental Table 1). Patients with LN or vasculitis had the highest frequency of infection-related deaths (2.3% and 2.5% of all patients, representing 14.0% and 13.0% of all deaths, respectively), whereas patients with MN had the highest frequency of malignancy-related deaths (2.1% of all patients, representing 10.2% of all deaths) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Variation in the rates and causes of allograft failure by cause of ESRD. Cumulative incidence plots of the competing events of death and allograft failure excluding death as a cause. “Graft failure” represents allograft failure due to causes other than death. “Death” represents allograft failure due to death. The cumulative incidence of “Graft failure” and “Death” combined represents the total incidence of allograft failure due to any cause. DN, diabetic nephropathy; TX, transplantation.

Table 2.

Rates of death, all-cause allograft failure, and allograft failure excluding death as a cause, among United States adult kidney transplant recipients with ESRD due to GN, DN, or ADPKD

| Outcome | % with Event | Number of Events | Years at Risk | Event Rate Per 100 PYs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | ||||

| FSGS | 16.1 | 2131 | 85,846 | 2.48 |

| IgAN | 7.7 | 568 | 48,057 | 1.18 |

| MN | 20.6 | 463 | 15,117 | 3.06 |

| MPGN | 19.7 | 390 | 14,013 | 2.78 |

| LN | 16.2 | 952 | 38,350 | 2.48 |

| Vasculitis | 19.1 | 261 | 8133 | 3.20 |

| DN | 36.1 | 20,631 | 330,963 | 6.23 |

| ADPKD | 15.8 | 2923 | 119,655 | 2.44 |

| All-cause allograft failure | ||||

| FSGS | 32.8 | 4355 | 71,520 | 6.09 |

| IgAN | 20.1 | 1481 | 42,976 | 3.45 |

| MN | 34.8 | 784 | 12,933 | 6.06 |

| MPGN | 39.0 | 773 | 11,455 | 6.75 |

| LN | 32.3 | 1899 | 32,331 | 5.87 |

| Vasculitis | 27.3 | 373 | 7392 | 5.05 |

| DN | 43.9 | 25,096 | 298,076 | 8.42 |

| ADPKD | 23.6 | 4349 | 110,136 | 3.95 |

| Allograft failure excluding death as a cause | ||||

| FSGS | 23.7 | 3152 | 71,520 | 4.41 |

| IgAN | 15.4 | 1138 | 42,976 | 2.65 |

| MN | 23.0 | 517 | 12,933 | 4.00 |

| MPGN | 29.4 | 583 | 11,455 | 5.09 |

| LN | 24.3 | 1428 | 32,331 | 4.42 |

| Vasculitis | 14.8 | 203 | 7392 | 2.73 |

| DN | 19.2 | 10,972 | 298,076 | 3.68 |

| ADPKD | 12.5 | 2313 | 110,136 | 2.10 |

PYs, person years; DN, diabetic nephropathy.

Table 3.

Frequency of secondary outcomes (cause of death, cause of allograft failure, and early complications), by cause of ESRD, n=107,778

| Outcome | Primary GN subtypes | Secondary GN subtypes | Non-GN Comparator Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSGS n=13,272 | IgAN n=7379 | MN n=2249 | MPGN n=1980 | LN n=5884 | Vasculitis n=1367 | DN n=57,190 | ADPKD n=18,457 | |

| Causes of death, n (%) | ||||||||

| Cardiovascular | 641 (4.8) | 154 (2.1) | 146 (6.5) | 113 (5.7) | 308 (5.2) | 46 (3.4) | 6431 (11.2) | 742 (4.0) |

| Infection | 241 (1.8) | 63 (0.9) | 43 (1.9) | 42 (2.1) | 133 (2.3) | 34 (2.5) | 2157 (3.8) | 297 (1.6) |

| Malignancy | 165 (1.2) | 62 (0.8) | 47 (2.1) | 32 (1.6) | 49 (0.8) | 24 (1.8) | 847 (1.5) | 290 (1.6) |

| Other | 546 (4.1) | 154 (2.1) | 115 (5.1) | 104 (5.3) | 256 (4.4) | 78 (5.7) | 5085 (8.9) | 776 (4.2) |

| Missing cause | 539 (4.1) | 135 (1.8) | 112 (5.0) | 99 (5.0) | 207 (3.5) | 79 (5.8) | 6111 (10.7) | 818 (4.4) |

| Patient still alive at last follow-up | 11,141 (83.9) | 6811 (92.3) | 1786 (79.4) | 1590 (80.3) | 4932 (83.8) | 1106 (80.9) | 36,559 (63.9) | 15,534 (84.2) |

| Causes of allograft failure, n (%) | ||||||||

| Primary nonfunction | 178 (1.3) | 44 (0.6) | 20 (0.9) | 22 (1.1) | 59 (1.0) | <10 (<1%) | 643 (1.0) | 142 (0.8) |

| Graft thrombosis | 148 (1.1) | 66 (0.9) | 21 (0.9) | 18 (0.9) | 67 (1.1) | 17 (1.2) | 505 (0.9) | 196 (1.1) |

| Acute rejection | 430 (3.2) | 156 (2.1) | 54 (2.4) | 53 (2.7) | 244 (4.1) | 28 (2.1) | 1231 (2.2) | 284 (1.5) |

| Chronic rejection | 973 (7.3) | 363 (4.9) | 172 (7.6) | 170 (8.6) | 514 (8.7) | 75 (5.5) | 3226 (5.1) | 756 (4.1) |

| Infection | 94 (0.7) | 32 (0.4) | 25 (1.1) | 16 (0.8) | 38 (0.7) | <10 (<1%) | 528 (0.8) | 128 (0.7) |

| Recurrent GN | 355 (2.7) | 121 (1.6) | 75 (3.3) | 110 (5.6) | 67 (1.1) | <10 (<1%) | 253 (0.4) | 57 (0.3) |

| Other | 509 (3.8) | 176 (2.4) | 82 (3.6) | 111 (5.6) | 241 (4.1) | 39 (2.9) | 1854 (3.2) | 440 (2.4) |

| Death | 1204 (9.1) | 343 (4.7) | 267 (11.9) | 190 (9.6) | 472 (8.0) | 171 (12.5) | 14,124 (24.7) | 2036 (11.0) |

| Missing cause | 464 (3.5) | 180 (2.4) | 68 (3.0) | 83 (4.2) | 197 (3.4) | 20 (1.5) | 2732 (4.8) | 310 (1.7) |

| Graft functioning at last follow-up | 8921 (67.2) | 5902 (79.9) | 1466 (65.1) | 1207 (61.0) | 3988 (67.7) | 994 (72.7) | 32,094 (56.1) | 14,108 (76.4) |

| Early post-transplant complications, n (%) | ||||||||

| DGF | 2032 (15.3) | 662 (9.0) | 329 (14.6) | 267 (13.5) | 751 (12.8) | 163 (11.9) | 11,222 (19.6) | 2230 (12.1) |

| Missing | 52 (0.4) | 27 (0.4) | 12 (0.5) | 17 (0.9) | 36 (0.6) | <10 (<0.5) | 299 (0.5) | 66 (0.4) |

| Oliguria | 1056 (8.0) | 385 (5.2) | 164 (7.3) | 133 (6.7) | 400 (6.8) | 84 (6.1) | 5476 (9.6) | 1196 (6.5) |

| Missing | 2847 (21.5) | 1531 (20.8) | 543 (24.1) | 518 (26.2) | 1299 (22.1) | 285 (20.9) | 13,712 (24.0) | 4240 (23.0) |

| Acute rejection | 237 (1.8) | 122 (1.7) | 32 (1.4) | 31 (1.6) | 112 (1.9) | 21 (1.5) | 895 (1.6) | 219 (1.2) |

| Missing | 5930 (44.7) | 3057 (41.4) | 1138 (50.6) | 1040 (52.5) | 2689 (45.7) | 563 (41.2) | 28,150(49.2) | 8346 (45.2) |

DN, diabetic nephropathy.

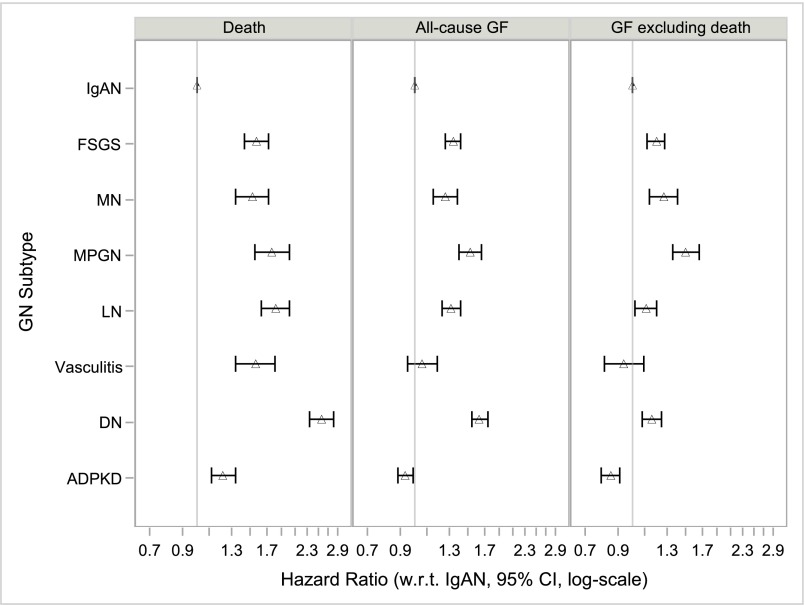

Adjusting for differences in case mix did not eliminate these mortality differences (Supplemental Figure 1, Table 4). After stratifying by year of transplantation (model 1) and adjusting for sociodemographic (model 2), comorbidity (model 3), and transplant-related (model 4) factors, relative hazards for death remained significantly elevated for all comparator GN subtypes versus IgAN: hazard ratio (HR)FSGS was 1.57 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.43 to 1.72), HRMN was 1.52 (95% CI, 1.34 to 1.72), HRMPGN was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.55 to 2.01), HRLN was 1.82 (95% CI, 1.63 to 2.02), and HRvasculitis was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.34 to 1.81) (Figure 3). Mortality was also slightly higher for patients with ADPKD (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.34), whereas those with diabetic nephropathy had the highest adjusted mortality of all groups (HR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.35 to 2.82). Findings were not materially different in terms of the direction and magnitude of effect estimates, or their clinical interpretation, when performing a complete case (n=40,460) analysis (Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Table 2).

Table 4.

HRs with 95% CIs for the primary outcomes of death, all-cause allograft failure, and allograft failure excluding death as a cause (competing risks model), by cause of ESRD, n=107,778

| Outcome | Primary GN Subtypes | Secondary GN Subtypes | Non-GN Comparator Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSGS n=13,272 | IgAN n=7379 | MN n=2249 | MPGN n=1980 | LN n=5884 | Vasculitis n=1367 | DN n=57,190 | ADPKD n=18,457 | |

| Death | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 2.10 | Ref | 2.56 | 2.29 | 2.09 | 2.76 | 5.36 | 2.06 |

| (2.04 to 2.16) | (2.46 to 2.66) | (2.20 to 2.39) | (2.02 to 2.16) | (2.63 to 2.89) | (5.22 to 5.50) | (2.01 to 2.12) | ||

| Model 2 | 1.70 | Ref | 1.64 | 1.95 | 2.15 | 1.73 | 3.43 | 1.29 |

| (1.55 to 1,87) | (1.45 to 1.86) | (1.71 to 2.22) | (1.94 to 2.39) | (1.50 to 2.01) | (3.15 to 3.73) | (1.18 to 1.41) | ||

| Model 3 | 1.57 | Ref | 1.53 | 1.77 | 1.84 | 1.56 | 2.61 | 1.26 |

| (1.43 to 1.73) | (1.35 to 1.73) | (1.55 to 2.01) | (1.65 to 2.04) | (1.34 to 1.81) | (2.38 to 2.86) | (1.15 to 1.38) | ||

| Model 4 | 1.57 | Ref | 1.52 | 1.76 | 1.82 | 1.56 | 2.57 | 1.22 |

| (1.43 to 1.72) | (1.34 to 1.72) | (1.55 to 2.01) | (1.63 to 2.02) | (1.34 to 1.81) | (2.35 to 2.82) | (1.12 to 1.34) | ||

| All-cause allograft failure | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 1.76 | Ref | 1.74 | 1.91 | 1.69 | 1.47 | 2.43 | 1.13 |

| (1.73 to 1.80) | (1.69 to 1.78) | (1.86 to 1.97) | (1.65 to 1.73) | (1.42 to 1.52) | (2.39 to 2.47) | (1.11 to 1.16) | ||

| Model 2 | 1.44 | Ref | 1.36 | 1.68 | 1.48 | 1.16 | 1.90 | 0.97 |

| (1.36 to 1.53) | (1.24 to 1.48) | (1.54 to 1.83) | (1.38 to 1.58) | (1.03 to 1.30) | (1.80 to 2.00) | (0.91 to 1.03) | ||

| Model 3 | 1.36 | Ref | 1.29 | 1.56 | 1.33 | 1.04 | 1.69 | 0.96 |

| (1.28 to 1.44) | (1.18 to 1.40) | (1.42 to 1.70) | (1.24 to 1.43) | (0.93 to 1.17) | (1.59 to 1.79) | (0.90 to 1.02) | ||

| Model 4 | 1.34 | Ref | 1.26 | 1.52 | 1.32 | 1.06 | 1.63 | 0.93 |

| (1.26 to 1.42) | (1.15 to 1.38) | (1.40 to 1.66) | (1.23 to 1.42) | (0.95 to 1.19) | (1.54 to 1.74) | (0.88 to 0.99) | ||

| Allograft failure with death as a competing risk | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 1.59 | Ref | 1.42 | 1.79 | 1.59 | 0.98 | 1.19 | 0.76 |

| (1.49 to 1.71) | (1.28 to 1.57) | (1.62 to 1.98) | (1.47 to 1.72) | (0.85 to 1.14) | (1.12 to 1.27) | (0.71 to 0.81) | ||

| Model 2 | 1.30 | Ref | 1.36 | 1.62 | 1.15 | 0.97 | 1.17 | 0.88 |

| (1.21 to 1.39) | (1.23 to 1.51) | (1.46 to 1.79) | (1.06 to 1.24) | (0.84 to 1.13) | (1.10 to 1.25) | (0.81 to 0.94) | ||

| Model 3 | 1.24 | Ref | 1.32 | 1.56 | 1.11 | 0.90 | 1.24 | 0.89 |

| (1.16 to 1.33) | (1.19 to 1.47) | (1.41 to 1.72) | (1.03 to 1.21) | (1.78 to 1.05) | (1.15 to 1.33) | (0.82 to 0.95) | ||

| Model 4 | 1.20 | Ref | 1.27 | 1.50 | 1.11 | 0.94 | 1.16 | 0.85 |

| (1.12 to 1.28) | (1.14 to 1.41) | (1.36 to 1.66) | (1.02 to 1.20) | (0.81 to 1.09) | (1.08 to 1.25) | (0.79 to 0.91) | ||

Model 1, stratified by year of transplantation. Model 2, added sociodemographic variables: age, age*age, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region, insurance type, college. Model 3, added dialysis modality, dialysis vintage, comorbidities (unable to ambulate, coronary heart disease, cancer, congestive heart failure, COPD, CVA/TIA, diabetes, hypertension, current/recent smoker, PVD), BMI group, HCV status. Model 4, added transplant-related variables: ABO blood group, CIT, donor age, donor sex, donor race, HLA mismatch group, donor type (living/decreased/expanded criteria), PPRA, initial post-transplant immunosuppression (Alemtuzumab, Basiliximab, Daclizumab, or Thymoglobulin induction; Tacrolimus, Ciclosporin, Sirolimus, MMF, Azathioprine and/or steroid maintenance), previous blood transfusion, DGF. DN, diabetic nephropathy; Ref, reference; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; BMI, body mass index; CIT, cold ischemia time; HLA, histocompatibility leukocyte antigen; PPRA, peak panel reactive antibody; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Figure 3.

Increased hazards for death and for allograft failure (including or excluding death as a cause) for comparator causes of ESRD compared to IgA nephropathy (IgAN). Model 4 (fully adjusted) HRs with 95% CIs for the primary outcomes of death, all-cause allograft failure, and allograft failure excluding death as a cause (competing risks model), by cause of ESRD, n=107,778. Model 4 stratified by year of transplantation and adjusted for age, age*age, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region, insurance type, college education, dialysis modality, dialysis vintage, comorbidities (unable to ambulate, coronary heart disease, cancer, congestive heart failure, COPD, CVA/TIA, diabetes, hypertension, current/recent smoker, PVD), BMI group, HCV status, ABO blood group, CIT, donor age, donor sex, donor race, HLA mismatch group, donor type (living/decreased/expanded criteria), PPRA, initial post-transplant immunosuppression (Alemtuzumab, Basiliximab, Daclizumab, or Thymoglobulin induction; Tacrolimus, Ciclosporin, Sirolimus, MMF, Azathioprine and/or steroid maintenance), previous blood transfusion, and DGF. BMI, body mass index; CIT, cold ischemia time; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DN, diabetic nephropathy; HLA, histocompatibility leukocyte antigen; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; PPRA, peak panel reactive antibody; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Allograft Survival

Allograft failure due to any cause was observed in 39,110 (36.3%) patients after a median follow-up of 4.7 (IQR, 2.0–8.3) years. Death with a functioning allograft accounted for 18,806 (48.1%) of allograft failure cases. Among GN subtypes, the rate of all-cause allograft failure was lowest in IgAN (3.5 events per 100 person years) and highest in MPGN (6.8 events per 100 person years) (Figure 2, Table 2). The rate of allograft failure was lower for all GN subtypes when compared with diabetic nephropathy (8.4 events per 100 person years), but only lower for IgAN when compared with ADPKD (4.0 events per 100 person years). After excluding death as a cause, allograft failure among GN subtypes ranged from 2.7 events per 100 person years in IgAN to 5.1 events per 100 person years in MPGN, and exceeded that for diabetic nephropathy (3.7 events per 100 person years) in some GN subtypes. The relative contributions to allograft failure from death and from nonfatal causes differed by GN subtype. Death was particularly frequent as a cause of allograft failure among patients with vasculitis (12.5% of all patients, representing 45.8% of all cases of allograft failure in vasculitis), whereas patients with MPGN had a disproportionately high risk for GN recurrence as a cause of allograft failure (5.6% of all patients, representing 14.2% of cases of allograft failure in MPGN) (Table 3).

Stratifying by year of transplantation (model 1) and adjusting for sociodemographic (model 2), comorbidity (model 3), and transplant-related (model 4) factors, did not eliminate the excess risk for allograft failure observed among patients with FSGS, MN, MPGN, or LN, although rates of all-cause allograft failure or of allograft failure excluding death as a cause were comparable to those of patients with IgAN for patients with vasculitis (Supplemental Figures 3 and 4, Table 4). For the outcome of all-cause allograft failure, model 4 (fully adjusted) HRFSGS was 1.34 (95% CI, 1.26 to 1.42), HRMN was 1.26 (95% CI, 1.15 to 1.38), HRMPGN was 1.52 (95% CI, 1.40 to 1.66), HRLN was 1.32 (95% CI, 1.23 to 1.42), and HRvasculitis was 1.06 (95% CI, 0.95 to 1.19) (Figure 3). These HRs were within a spectrum flanked by ADPKD (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.88 to 0.99) and diabetic nephropathy (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.54 to 1.74). For the outcome of allograft failure excluding death as a cause (competing risk framework), HRFSGS was 1.20 (95% CI, 1.12 to 1.28), HRMN was 1.27 (95% CI, 1.14 to 1.41), HRMPGN was 1.50 (95% CI, 1.36 to 1.66), HRLN was 1.11 (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.20), and HRvasculitis was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.09) (Figure 3). After excluding death as a cause, rates of allograft failure remained lowest for ADPKD (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79 to 0.91) but were now also lower for diabetic nephropathy (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.25) when compared with some GN subtypes. Effect estimates were similar when death was modeled as a censoring event (sensitivity analysis) rather than as a competing risk (primary analysis) (Supplemental Figure 5, Supplemental Table 3). Findings were also not materially different when performing a complete case (n=40,460) analysis (Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Table 2).

Early Post-Transplant Complications

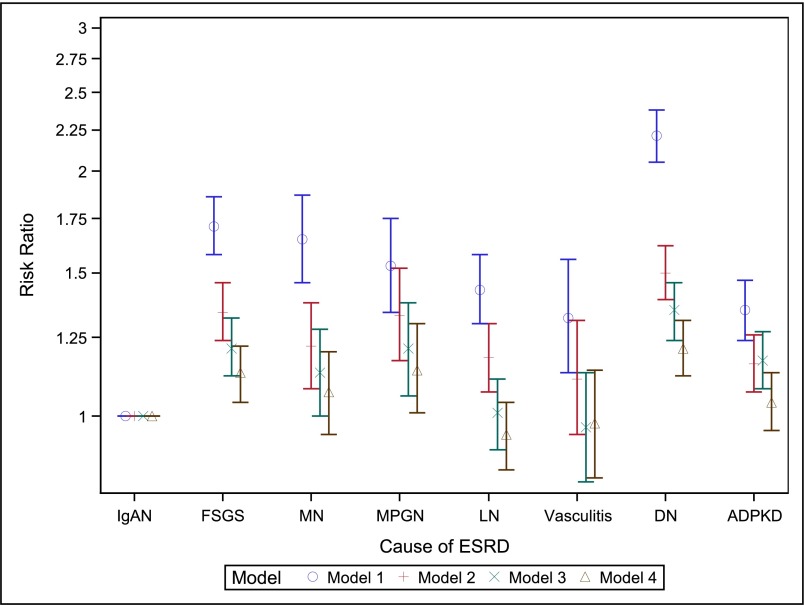

The unadjusted frequencies of acute rejection, postoperative oliguria, delayed graft function (DGF), or allograft failure due to primary transplant nonfunction differed by GN subtype (Table 3). As data were most complete for the secondary outcome of DGF, we selected this for multivariate modeling. After full adjustment (model 4), apparent differences in DGF frequency by cause of ESRD were almost entirely explained by differences in case mix, and a modestly increased relative risk for DGF remained only for patients with FSGS (relative risk, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.22), MPGN (relative risk, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.20), or diabetic nephropathy (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.31) (Figure 4, Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 4.

Risk ratios with 95% CIs for the secondary outcome of DGF, showing attenuation of effect estimates with sequential addition of covariates to multivariate Poisson models (n=107,272, after excluding n=560 with missing outcome). Model 1, adjusted for year of transplantation. Model 2, added sociodemographic variables: age, age*age, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region, insurance type, college. Model 3, added dialysis modality, dialysis vintage, comorbidities (unable to ambulate, coronary heart disease, cancer, congestive heart failure, COPD, CVA/TIA, diabetes, hypertension, current/recent smoker, PVD), BMI group, HCV status. Model 4, added transplant-related variables: ABO blood group, CIT, donor age, donor sex, donor race, HLA mismatch group, donor type (living/decreased/expanded criteria), PPRA, initial post-transplant immunosuppression (Alemtuzumab, Basiliximab, Daclizumab, or Thymoglobulin induction; Tacrolimus, Ciclosporin, Sirolimus, MMF, Azathioprine and/or steroid maintenance), previous blood transfusion. BMI, body mass index; CIT, cold ischemia time; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DN, diabetic nephropathy; HLA, histocompatibility leukocyte antigen; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; PPRA, peak panel reactive antibody; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Discussion

In this study of 32,131 adult patients with ESRD attributed to GN, 57,190 with ESRD attributed to diabetes, and 18,457 with ESRD attributed to ADPKD, who received a first kidney transplant in the United States between 1996 and 2011, we identified significant heterogeneity among six common GN subtypes with respect to rates of long-term patient and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Even after adjusting for multiple patient- and transplant-related factors, patients with any of the five comparator GN subtypes (FSGS, MN, MPGN, LN, or vasculitis) had significantly higher rates of death than patients with IgAN. Patients with four of these five comparator GN subtypes (FSGS, MN, MPGN, or LN) were also more likely than patients with IgAN to experience allograft failure (with or without considering death as a cause), whereas allograft failure rates among patients with vasculitis were comparable to those of patients with IgAN. When compared with patients with other causes of kidney disease, and after adjusting for case mix, patients with any of these six GN subtypes had lower mortality than patients with diabetic nephropathy but higher mortality (with the exception of patients with IgAN) than patients with ADPKD. When examining all-cause allograft failure, this same pattern emerged, i.e., adjusted rates of all-cause allograft failure were higher than for ADPKD and lower than for diabetic nephropathy, among all GN subtypes. After excluding death as a cause, however, adjusted rates of allograft failure remained higher than for patients with ADPKD for all groups, but appeared only lower than for patients with diabetic nephropathy among patients with IgAN or vasculitis. Meaningful assessment of shorter-term outcomes was limited by a high frequency of missing data, although risks for DGF (missing <10%) were largely similar across GN subtypes after accounting for differences in case mix.

We are aware of one recent European study that adopted a similar methodologic approach.13 This smaller study reported 15-year cumulative incidences of allograft failure, excluding death as a cause, of 31%, 37%, 40%, and 47% for patients with IgAN, MN, FSGS, and MPGN, respectively—strikingly similar to those we report (32%, 38%, 42%, and 46%, respectively). However, secondary GN subtypes were not examined, substantially fewer covariates were considered, and United States patients were excluded. Otherwise, prior studies examining long-term outcomes in transplant recipients with GN have generally grouped all GN subtypes together into a single disease category,1,2,10,14–17 focused primarily on GN recurrence as an outcome,7–12 or compared an individual GN subtype to all other causes of ESRD combined.14,18–27

We posit that our study findings have meaningful clinical and research implications. By elucidating GN subtype-specific risks after kidney transplantation, our findings can inform the counseling of patients and potential living donors before transplantation, allow post-transplant surveillance strategies to be better tailored toward individual patient needs, and guide the design of future studies aimed at identifying the underlying reasons for observed differences. For example, patients with vasculitis were highly likely to lose their allograft due to death (almost half of all cases, compared with between one quarter and one third of cases among other GN subtypes), but least likely to lose their allograft due to other causes; accordingly, detection and treatment of cardiovascular disease, infections, or malignancy—both before and after kidney transplantation—might assume greater relative importance than intensive post-transplant immune monitoring in this patient group. Additionally, the favorable allograft outcomes we observed among patients with vasculitis might reassure those nephrologists with residual uncertainties regarding the appropriateness and timing of transplantation in this patient group.28

In contrast, the significantly inferior patient and allograft survival rates we observed among patients with MPGN merit further discussion. In our cohort, patients with MPGN had a 76% higher mortality rate, a 52% higher all-cause allograft failure rate, and a 50% higher allograft failure rate after excluding death as a cause, when compared with otherwise similar patients with IgAN. These increased risks persisted despite adjusting for many other factors associated with adverse allograft outcomes, including HCV serologic status. Shedding some light on this finding, we identified a higher frequency of GN recurrence as a cause of allograft failure among patients with MPGN, consistent with prior reports.8 However, we could not examine cases of GN recurrence that did not result in allograft failure, that were not confirmed by biopsy, or that were simply not reported to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). Nevertheless, we suggest that heightened vigilance for early signs of allograft dysfunction might be particularly prudent in this patient group, and that future studies involving protocol biopsies be performed in patients with ESRD attributed to GN to further explore this finding.

Our study has several limitations. Although our primary outcomes are likely to be completely and accurately measured, data were frequently missing for many of our secondary outcomes; thus, these secondary outcome data should be viewed as hypothesis-generating and not definitive. With regard to our primary exposure, GN subtype designations in the US Renal Data System (USRDS) are reported to be highly specific but poorly sensitive.29 Thus, the generalizability of our findings to patients misclassified in the USRDS or lacking a biopsy-confirmed GN diagnosis cannot be determined. Misclassification or under-reporting of covariate data, for example comorbidities,30 might have resulted in incomplete adjustment for confounding and associations cannot be assumed to be causative. Furthermore, the underlying reasons for observed differential outcomes between GN subtypes could not directly be determined. In particular, medication data were lacking and thus we could not disentangle the influence of GN itself from the influence of prior and ongoing immunosuppressive treatments on patient outcomes. Finally, although our approach to examining outcomes according to histologically-defined GN subtypes represents a major advance upon prior studies in which GN subtypes were grouped in to a single disease category, we recognize that heterogeneity within subtypes still persists. We welcome a recent proposal to transition from a histopathology- to pathophysiology-based GN classification system, although anticipate that it will take many years for this approach to be developed, validated, and ultimately adopted by the USRDS.31

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study has numerous strengths. By studying a population-based cohort, we had ample power to detect clinically meaningful between-group differences and could simultaneously adjust for multiple factors known to associate with post-transplant outcomes.32–35 We modeled death primarily as a competing risk, an approach increasingly favored in transplant outcomes studies.13,36 We handled missing data using multiple imputation, thus minimizing bias introduced by the nonrandom nature of missing data.37 Finally, we included patients with two non-GN–related kidney diseases as external comparator groups, so that outcomes in patients with GN could be meaningfully interpreted within the broader context of outcomes in patients with other major causes of ESRD.

To conclude, we identified significant differences in patient and allograft survival after first kidney transplantation among patients with ESRD attributed to the six GN subtypes most commonly resulting in ESRD in the United States. Patients with IgAN experienced excellent outcomes overall, comparable to those in patients with ADPKD, and allograft survival (but not patient survival) was also favorable for patients with vasculitis. In contrast, patient and allograft survival were significantly poorer than for patients with IgAN for patients with FSGS, MN, or MPGN, in whom rates of allograft failure excluding death as a cause were no better, or higher, than in patients with diabetic nephropathy. We do not propose that patients with an expected poorer outcome (e.g., those with MPGN) be precluded from kidney transplantation, as their survival is still likely to be prolonged by undergoing transplantation as compared with remaining on dialysis2 and, on the basis of our data, is superior to that of transplant recipients with ESRD due to diabetic nephropathy. Nevertheless, in light of our findings, we advocate for increased awareness of disease-specific risks when preparing patients with GN for kidney transplantation, monitoring them for complications after transplantation, and designing future transplant outcomes studies. Ultimately, elucidating the underlying reasons for observed differences, and identifying modifiable factors amenable to intervention, will be key to optimizing outcomes for patients with any and all GN subtypes.

Concise Methods

For a complete description of the methods please see Supplemental Material.

Patient Population

We studied all adult patients (≥18 years) with ESRD attributed to any of six selected GN subtypes (FSGS, IgAN, MN, MPGN, LN, or vasculitis), diabetic nephropathy, or ADPKD, who received a first kidney transplant in the United States between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2011.

Data Sources

The USRDS, incorporating data from UNOS, was the data source for all exposure, outcome, and covariate data.

Primary Exposure

GN subtype (FSGS, IgAN, MN, MPGN, LN, or vasculitis) was the primary exposure. Two non-GN–related causes of ESRD (diabetic nephropathy and ADPKD) were examined as external comparator groups. Cause of ESRD was defined as that reported in a patient’s first Medical Evidence Report (MER). Nephrologists must submit this document, by federal mandate, within 90 days of a patient commencing a new ESRD treatment (dialysis or transplantation). Cause of ESRD does not need to be confirmed by kidney biopsy, although a category “GN not histologically examined” exists for such cases. A prior validation study determined that selection of a specific GN subtype had a high positive predictive value (>90%), but low sensitivity (≤30%).29

Primary Outcomes

We studied three primary outcomes: (1) patient death, (2) all-cause allograft failure, and (3) allograft failure excluding death as a cause. We defined all-cause allograft failure as death, return to dialysis, or retransplantation. We defined allograft failure excluding death as a cause as return to dialysis or retransplantation, with death modeled as a competing risk (primary analysis) or as a censoring event (sensitivity analysis). Administrative censoring occurred on January 1, 2012.

Secondary Outcomes

We studied cause of death (as reported to the USRDS in death notification forms), cause of allograft failure (as reported to UNOS in transplant recipient follow-up forms), and a selection of early post-transplant complications (acute rejection before discharge from the hospital [early acute rejection, as reported to UNOS in transplant recipient registration forms, without requirement for biopsy confirmation], urine output ≤40 ml in the first 24 hours [postoperative oliguria, as reported to UNOS as a yes/no variable in transplant recipient registration forms], or need for dialysis within the first week [DGF, as reported to UNOS in transplant recipient registration forms]) as secondary study outcomes.

Covariates

Demographic variables included recipient age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, and geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, or other), as reported in MERs. Socioeconomic variables included insurance payer at time of transplantation (Medicare, Medicaid, Employer Group Plan, Veterans Administration, or other), and attainment of college-level education at time of wait listing. Comorbidities included diabetes, heart failure, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, current/recent smoking, cancer, peripheral vascular disease, and inability to ambulate, as reported in a patient’s first MER, along with body mass index and HCV serologic status at time of transplantation. Dialysis variables included modality and duration of prior dialysis, if any. Transplant-related variables included donor characteristics (donor age, race, sex, type [living, standard deceased, expanded criteria deceased]), immunologic factors (ABO blood group, 6-antigen histocompatibility leukocyte antigen mismatch, recipient peak panel reactive antibody percentage, prior blood transfusion), cold-ischemic time, and baseline induction and maintenance immunosuppressive drugs received during and at discharge from the initial hospital admission.

Statistical Analyses

Unadjusted Analyses

We summarized categoric variables as frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as means and SDs, or as medians and IQRs, as appropriate. We computed rates of death, all-cause allograft failure, and allograft-failure excluding death as a cause for each cause of ESRD from the number of events and person-time observed. We created stacked cumulative incidence plots depicting the competing events of death and causes of allograft failure other than death for each of the eight causes of ESRD using the cumulative incidence function modeled by flexible parametric models.38

Adjusted Analyses

We used stratified Cox proportional hazards regression to compute HRs with 95% CIs for each of the three primary outcomes, with IgAN as the reference group and year of transplant as the stratum. For the outcome of allograft failure excluding death as a cause, we adopted two approaches: for our primary analysis, death was treated as a competing risk using the Kaplan–Meier multiple imputation method to obtain subdistribution HRs.39,40 As a sensitivity analysis death was instead modeled as a censoring event to obtain cause-specific HRs. As a secondary outcome, we computed relative risks for DGF by GN subtype using modified Poisson models,41,42 after excluding 560 patients who were missing data for this outcome. In all analyses, we added covariates to regression models sequentially to account for confounding. Model 1 included cause of ESRD (and year of transplant in Poisson models, which were not stratified by year). Model 2 additionally adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic factors. Model 3 additionally adjusted for comorbidities and for dialysis-related factors. Model 4 additionally adjusted for transplant-related factors.

We used log(-log) survival curves and plots of Loess smoothed scaled Schoenfeld residuals to assess the adequacy of the Cox proportional hazards models. We assumed covariate data to be missing at random and used multiple imputation to handle these missing data.37 Complete case analysis results are also reported.

Statistical analyses were performed using a combination of SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), Stata version 13.1 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; StataCorp., College Station, TX) and R version 3.1.2. The Stanford University School of Medicine Internal Review Board approved the study.

Disclosures

W.C.W. reports having served as an advisor or consultant, unrelated to the topic of this manuscript, to Akebia (Cambridge, MA), AMAG (Waltham, MA), Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA), Astra-Zeneca (London, U.K.), Medtronic (Minneapolis, MN), Relypsa (Redwood City, CA), Vifor-Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma (Zurich, Switzerland), and Zoll (Chelmsford, MA). R.A.L. reports having served as an advisor or consultant, unrelated to the topic of this manuscript, to Relypsa (Redwood City, CA), Fibrogen (San Francisco, CA), and Mallinckrodt (Chesterfield, U.K.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M.M.O’S. was supported by a fellowship award from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. The Stanford nephrology fellowship program was supported by grant T32DK007357 from the National Institutes of Health.

This manuscript was reviewed and approved for publication by an officer of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Data reported herein were supplied by the US Renal Data System. Interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the US Government. Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in manuscript writing, or in the decision to submit this report for publication.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2016020126/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rabbat CG, Thorpe KE, Russell JD, Churchill DN: Comparison of mortality risk for dialysis patients and cadaveric first renal transplant recipients in Ontario, Canada. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 917–922, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron JI, Whiteside C, Katz J, Devins GM: Differences in quality of life across renal replacement therapies: a meta-analytic comparison. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 629–637, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Renal Data System: 2014 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Kaplan B. Lack of improvement in renal allograft survival despite a marked decrease in acute rejection rates over the most recent era. Am J Transplant 4: 378–383, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Arend SM, Mallat MJ, Westendorp RJ, van der Woude FJ, van Es LA: Patient survival after renal transplantation; more than 25 years follow-up. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 1672–1679, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chailimpamontree W, Dmitrienko S, Li G, Balshaw R, Magil A, Shapiro RJ, Landsberg D, Gill J, Keown PA; Genome Canada Biomarkers in Transplantation Group : Probability, predictors, and prognosis of posttransplantation glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 843–851, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briganti EM, Russ GR, McNeil JJ, Atkins RC, Chadban SJ: Risk of renal allograft loss from recurrent glomerulonephritis. N Engl J Med 347: 103–109, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hariharan S, Adams MB, Brennan DC, Davis CL, First MR, Johnson CP, Ouseph R, Peddi VR, Pelz CJ, Roza AM, Vincenti F, George V: Recurrent and de novo glomerular disease after renal transplantation: a report from Renal Allograft Disease Registry (RADR). Transplantation 68: 635–641, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moroni G, Longhi S, Quaglini S, Rognoni C, Simonini P, Binda V, Montagnino G, Messa P: The impact of recurrence of primary glomerulonephritis on renal allograft outcome. Clin Transplant 28: 368–376, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulay AV, van Walraven C, Knoll GA. Impact of immunosuppressive medication on the risk of renal allograft failure due to recurrent glomerulonephritis. Am J Transplant 9: 804–811, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Toledo K, Pérez-Sáez MJ, Navarro MD, Ortega R, Redondo MD, Agüera ML, Rodríguez-Benot A, Aljama P: Impact of recurrent glomerulonephritis on renal graft survival. Transplant Proc 43: 2182–2186, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pippias M, Stel VS, Aresté-Fosalba N, Couchoud C, Fernandez-Fresnedo G, Finne P, Heaf JG, Hoitsma A, De Meester J, Pálsson R, Ravani P, Segelmark M, Traynor JP, Reisæter AV, Caskey FJ, Jager KJ: Long-term Kidney Transplant Outcomes in Primary Glomerulonephritis: Analysis From the ERA-EDTA Registry [published online ahead of print November 19, 2015]. Transplantation doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chelamcharla M, Javaid B, Baird BC, Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS: The outcome of renal transplantation among systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 3623–3630, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibrahim H, Rogers T, Casingal V, Sturdevant M, Tan M, Humar A, Gillingham K, Matas A: Graft loss from recurrent glomerulonephritis is not increased with a rapid steroid discontinuation protocol. Transplantation 81: 214–219, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kukla A, Chen E, Spong R, Weber M, El-Shahawi Y, Gillingham K, Matas AJ, Ibrahim HN: Recurrent glomerulonephritis under rapid discontinuation of steroids. Transplantation 91: 1386–1391, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL: Impact of cadaveric renal transplantation on survival in patients listed for transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1859–1865, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunnapradist S, Chung P, Peng A, Hong A, Chung P, Lee B, Fukami S, Takemoto SK, Singh AK: Outcomes of renal transplantation for recipients with lupus nephritis: analysis of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network database. Transplantation 82: 612–618, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadiyala A, Mathew AT, Sachdeva M, Sison CP, Shah HH, Fishbane S, Jhaveri KD: Outcomes following Kidney transplantation in IgA nephropathy: a UNOS/OPTN analysis. Clin Transplant 29: 911–919, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moroni G, Gallelli B, Quaglini S, Banfi G, Montagnino G, Messa P. Long-term outcome of renal transplantation in adults with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Transplant Int 23: 208–216, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Moroni G, Gallelli B, Quaglini S, Leoni A, Banfi G, Passerini P, Montagnino G, Messa P: Long-term outcome of renal transplantation in patients with idiopathic membranous glomerulonephritis (MN). Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 3408–3415, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen J, Gill J, Shangguan M, Sampaio MS, Bunnapradist S: Outcomes of renal transplantation in recipients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Clin Transplant 25: 380–387, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward MM: Outcomes of renal transplantation among patients with end-stage renal disease caused by lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 57: 2136–2143, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choy BY, Chan TM, Lo SK, Lo WK, Lai KN: Renal transplantation in patients with primary immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 2399–2404, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hruskova Z, Stel VS, Jayne D, Aasarød K, De Meester J, Ekstrand A, Eller K, Heaf JG, Hoitsma A, Martos Jimenéz C, Ravani P, Wanner C, Tesar V, Jager KJ: Characteristics and Outcomes of Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Wegener) and Microscopic Polyangiitis Requiring Renal Replacement Therapy: Results From the European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association Registry. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 613–620, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moroni G, Casati C, Quaglini S, Gallelli B, Banfi G, Montagnino G, Messa P: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type I in renal transplantation patients: a single-center study of a cohort of 68 renal transplants followed up for 11 years. Transplantation 91: 1233–1239, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang W, Bose B, McDonald SP, Hawley CM, Badve SV, Boudville N, Brown FG, Clayton PA, Campbell SB, Peh CA, Johnson DW: The outcomes of patients with ESRD and ANCA-associated vasculitis in Australia and New Zealand. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 773–780, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little MA, Hassan B, Jacques S, Game D, Salisbury E, Courtney AE, Brown C, Salama AD, Harper L: Renal transplantation in systemic vasculitis: when is it safe? Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3219–3225, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Layton JB, Hogan SL, Jennette CE, Kenderes B, Krisher J, Jennette JC, McClellan WM: Discrepancy between Medical Evidence Form 2728 and renal biopsy for glomerular diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2046–2052, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnan M, Weinhandl ED, Jackson S, Gilbertson DT, Lacson E Jr: Comorbidity ascertainment from the ESRD Medical Evidence Report and Medicare claims around dialysis initiation: a comparison using US Renal Data System data. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 802–812, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sethi S, Haas M, Markowitz GS, D'Agati VD, Rennke HG, Jennette JC, Bajema IM, Alpers CE, Chang A, Cornell LD, Cosio FG, Fogo AB, Glassock RJ, Hariharan S, Kambham N, Lager DJ, Leung N, Mengel M, Nath KA, Roberts IS, Rovin BH, Seshan SV, Smith RJ, Walker PD, Winearls CG, Appel GB, Alexander MP, Cattran DC, Casado CA, Cook HT, De Vriese AS, Radhakrishnan J, Racusen LC, Ronco P, Fervenza FC: Mayo Clinic/Renal Pathology Society Consensus Report on Pathologic Classification, Diagnosis, and Reporting of GN. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1278–1287, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Chertow GM, Brenner BM, Mackenzie HS, Milford EL: Non-immunologic predictors of chronic renal allograft failure: data from the United Network of Organ Sharing. Kidney Int Suppl 52: S48–S51, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cole E, Naimark D, Aprile M, Wade J, Cattran D, Pei Y, Fenton S, Robinette M, Zaltsman J, Bear R, Cardella C: An analysis of predictors of long-term cadaveric renal allograft survival. Clin Transplant 9: 282–288, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meier-Kriesche HU, Arndorfer JA, Kaplan B: The impact of body mass index on renal transplant outcomes: a significant independent risk factor for graft failure and patient death. Transplantation 73: 70–74, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu C, Evans I, Joseph R, Shapiro R, Tan H, Basu A, Smetanka C, Khan A, McCauley J, Unruh M: Comorbid conditions in kidney transplantation: association with graft and patient survival. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3437–3444, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arce CM, Lenihan CR, Montez-Rath ME, Winkelmayer WC: Comparison of longer-term outcomes after kidney transplantation between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites in the United States. Am J Transplant 15: 499–507, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Montez-Rath ME, Winkelmayer WC, Desai M: Addressing missing data in clinical studies of kidney diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1328–1335, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinchliffe SR, Lambert PC: Flexible parametric modelling of cause-specific hazards to estimate cumulative incidence functions. BMC Med Res Methodol 13: 13, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruan PK, Gray RJ: Analyses of cumulative incidence functions via non-parametric multiple imputation. Stat Med 27: 5709–5724, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allignol A, Beyersmann J: Software for fitting nonstandard proportional subdistribution hazards models. Biostatistics 11: 674–675, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zou G: A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 159: 702–706, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP: Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 157: 940–943, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.