Abstract

Purpose: This study explored the factors that influence mentors in the profession of physiotherapy (PT) in Canada when engaging in a mentorship relationship. Methods: We conducted a quantitative, cross-sectional, Web-based survey. The target population consisted of Canadian physiotherapists who had experience as mentors. We used a modified Dillman approach to disseminate an online questionnaire to members of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association and its divisions using their respective e-blasts. We collected data on the nature and extent, facilitators, barriers, and benefits of mentorship and then analyzed them using descriptive statistics. Results: A total of 302 respondents were included in this study. They reported being a mentor to fellow PT colleagues (91%), undergraduate students (85%), graduate students (64%), and inter-professional colleagues (64%). We found that although many factors facilitated the respondents' ability to mentor, barriers to mentorship had minimal impact. Responses also reflected many perceived benefits of mentorship. Conclusions: This study provides novel evidence relating to the experience of mentorship from the perspective of mentors in the profession of PT. It reinforces the literature by highlighting the positive aspects of mentorship, and it underscores the continued need for support from professional associations, institutions, and physiotherapists to improve current mentorship experiences in PT.

Key Words : mentorship, survey

Abstract

Objectif : analyser les facteurs qui influencent les mentors dans la profession de physiothérapeute au Canada lorsqu'ils s'engagent dans une relation de mentorat. Méthodes : nous avons mené une enquête quantitative transversale sur le Web. La population cible était composée de physiothérapeutes canadiens ayant de l'expérience comme mentor. Nous avons utilisé une méthode de Dillman modifiée pour diffuser un questionnaire en ligne aux membres de l'Association canadienne de physiothérapie et à ses divisions au moyen de leurs envois de courriels respectifs. Nous avons recueilli des données sur la nature et la portée, les facteurs facilitants, les obstacles et les avantages du mentorat, puis les avons analysées à l'aide de statistiques descriptives. Résultats : au total, 302 répondants ont participé à l'étude. Ils ont indiqué être mentors pour des collègues physiothérapeutes (91 %), pour des étudiants de premier cycle (85 %), pour des étudiants des cycles supérieurs (64 %) et pour des collègues interprofessionnels (64 %). Nous avons constaté que de nombreux facteurs facilitent la capacité des répondants à faire du mentorat, alors que les obstacles au mentorat ont peu de répercussions. Les réponses reflètent aussi les nombreux avantages perçus du mentorat. Conclusions : cette étude fournit de nouvelles données probantes sur l'expérience de mentorat du point de vue des mentors au sein de la profession de physiothérapeute. Elle va dans le sens de la littérature en soulignant les aspects positifs du mentorat et met en évidence le besoin continu de soutien de la part des associations professionnelles, des établissements scolaires et des physiothérapeutes pour améliorer les expériences de mentorat en physiothérapie.

Mots clés : Canada, mentorat, mentors, physiothérapie

Mentorship describes a relationship focused on sharing knowledge and perspective between experienced mentors and motivated mentees with the aim of promoting professional development and self-actualization.1,2 In the context of health care, mentorship serves as a valuable resource, one that helps to bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice for health care professionals.3 Although research on mentorship has been carried out for decades, the literature has noticeable gaps. Current evidence supports the importance of mentorship in facilitating future success for mentees in terms of productivity,4 greater career satisfaction,5 better preparation to make career decisions,6 networking in a profession,4 and managing stress.7,8 However, most of the evidence is focused on the mentee, with limited information from the mentor's perspective. Furthermore, research on mentorship in health care heavily reflects the professions of nursing3,7,9,10 and medicine,4,11,12 whereas other professions, such as those in rehabilitation, are relatively under-represented. As such, the current literature insufficiently addresses certain issues that characterize the actual practice of mentorship. In the profession of physiotherapy (PT), there is a disparity between the high value placed on mentorship and the prevalence of its practice,13 underscoring the need for research in this area.

In addition to the aforementioned gaps in the literature, there is inconsistency between what constitutes mentorship and how it is defined. For example, in the clinical environment, the term mentorship is often assumed to be synonymous with preceptorship,7,9 although the two concepts are distinct.2 Preceptorship is usually a defined, task-focused, short-term arrangement, whereas mentorship is focused on progress and can flourish when it is sustained in the long term.7,9,14–16

Our study explored the factors that influence mentors when they engage in a mentorship relationship in the field of PT. Our study also provides some insight into what physiotherapists consider to be a typical mentorship relationship. The findings of this study will provide a deeper understanding of typical mentorship relationships in PT in Canada. This study also highlights any pertinent facilitators, barriers, and benefits of mentorship from the mentor's perspective that will inform future efforts to improve current mentorship practices in the field.

Methods

We conducted a quantitative, cross-sectional, Web-based survey. We obtained ethics approval in January 2015 from the University of Toronto Ethics Board (protocol 31008).

Participants

The target population for this study consisted of Canadian physiotherapists who had experience engaging in mentorship relationships as mentors. To be eligible to participate in this study, individuals had to be registered physiotherapists, be members of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA), have a minimum of 2 years of clinical experience,17–19 and self-identify as being a mentor at least once in PT.

Procedure

The measurement tool for the study was a self-administered electronic questionnaire that we created and administered using the online survey tool LimeSurvey (Fa. Carsten Schmitz, Hamburg, Germany). We developed the 79-item questionnaire using (1) relevant research regarding key concepts and components of mentorship, (2) pretested formats exploring the same variables and concepts,16 and (3) input from mentors in PT. The questionnaire consisted primarily of closed-ended questions and was divided into six sections: demographics, nature and extent of mentorship, facilitators, barriers, and benefits (see the online Appendix).

The demographics section collected data on participants' age, gender, area of residence, academic degree, number of years practising as a registered physiotherapist, location of work, type of work facility, and primary area of practice. Facilitators, barriers, and benefits were divided into personal (e.g., enjoy sharing knowledge, stress of the responsibility, improves knowledge base), relational (e.g., motivated mentee, lack of common goals, improves interpersonal skills), and organizational factors (e.g., sufficient time, poor learning environment, advances the profession as a whole) so that we could understand appropriate targets for future strategies encouraging mentorship. We piloted the final draft of the questionnaire with five PT colleagues to enhance clarity and ease of administration and to ensure that it could be completed in a reasonable amount of time. We made minor grammatical and formatting changes as a result of the feedback received.

We used a modified Dillman approach to recruit participants.20 We sent an email to the CPA and CPA division representatives, outlining the nature and purpose of our study and requesting permission to distribute the questionnaire through their respective e-blasts. Potential participants received an introductory e-blast invitation giving a description of and link to the questionnaire. Two and four weeks later, we sent a reminder/thank-you notice, describing the study and giving an online link to the questionnaire should the recipients want to participate. Five weeks after the first mailing, we sent a final notice to all potential participants to announce the closing date of the questionnaire. We collected data from February through March 2015.

We collected and used data from all questionnaires completed beyond the demographics section. To ensure anonymity, we collected no identifying data or IP addresses. Electronic data were password protected and stored on one computer.

Data analysis

We exported data from LimeSurvey and analyzed it using IBM SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). We obtained relevant statistics to describe participant characteristics and to explore the factors that affect mentors' ability to engage in mentorship. We performed descriptive summaries and frequency analyses and displayed them in tabular and graphical form, and we used Likert scales to gather data about the facilitators of, barriers to, and benefits of mentorship. As in previous studies,21,22 we considered “to a great extent” and “somewhat” as statements of agreement and “neutral,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree” as statements of disagreement.

Results

Of 412 individuals who expressed an interest in participating, 79 did not meet the inclusion criteria. In total, there were 333 survey responses; however, 31 responses were excluded because respondents did not participate beyond the demographics section. Of a total of 302 respondents who were included in the study, 295 returned complete questionnaires, and 7 returned incomplete questionnaires. Although approximately 9,970 individuals received the recruitment email, our inability to determine the number of potential respondents who met the eligibility criteria precluded calculating the actual response rate. Because of the abundance of data collected through this survey, some are being presented in another article; in particular, questions regarding leadership (no. 9), qualities that best characterize a mentor (no. 17), and factors that play a role in mentorship experiences (nos. 26–30) are not addressed in this article.

Respondent characteristics

The characteristics of study participants are summarized in Table 1. The majority of respondents were female (74%) and resided in central Canada (46%). On average, respondents were aged 45 years and had 20 years of experience as a physiotherapist. A full 57% of respondents indicated that the highest degree they had obtained was a baccalaureate. The largest percentage of respondents practised in a private facility (63%), in a large urban location (67%), and in the area of orthopaedics (69%). Only 37% of respondents had received formal training on being a mentor, and 19% were required to engage in mentorship relationships for work purposes (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Mentor Participants

| Participants (n=302) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | No. (%) |

| Age, y | 45.0 (11.1) | |

| Years of practice | 20.2 (11.3) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 79 (26.2) | |

| Female | 223 (73.8) | |

| Region*† | ||

| Western | 133 (44.0) | |

| Central | 140 (46.3) | |

| Eastern | 23 (7.6) | |

| Northern | 6 (2.0) | |

| Highest degree obtained | ||

| Certificate | 5 (1.7) | |

| Baccalaureate | 172 (57.0) | |

| Master's | 114 (37.7) | |

| Doctorate | 11 (3.6) | |

| Practice location | ||

| Large urban population centre | 203 (67.2) | |

| Medium population centre | 49 (16.2) | |

| Small population centre | 44 (14.6) | |

| Rural area | 6 (2.0) | |

| Type of facility | ||

| Acute | 47 (15.6) | |

| Rehabilitation | 16 (5.3) | |

| Private | 191 (63.2) | |

| Government | 9 (3.0) | |

| University | 11 (3.6) | |

| Community | 15 (5.0) | |

| Other | 13 (4.3) | |

| Area of practice† | ||

| Cardiorespiratory | 3 (1.0) | |

| Neurological | 15 (5.0) | |

| Orthopaedics | 208 (68.9) | |

| Geriatrics | 10 (3.3) | |

| Paediatrics | 9 (3.0) | |

| Academic | 5 (1.7) | |

| Administration | 15 (5.0) | |

| Multisystem | 30 (9.9) | |

| Other | 7 (2.3) | |

Region: Western=Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan; Central=Ontario and Quebec; Eastern=New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island; Northern=Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon Territory.

Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

Nature and extent

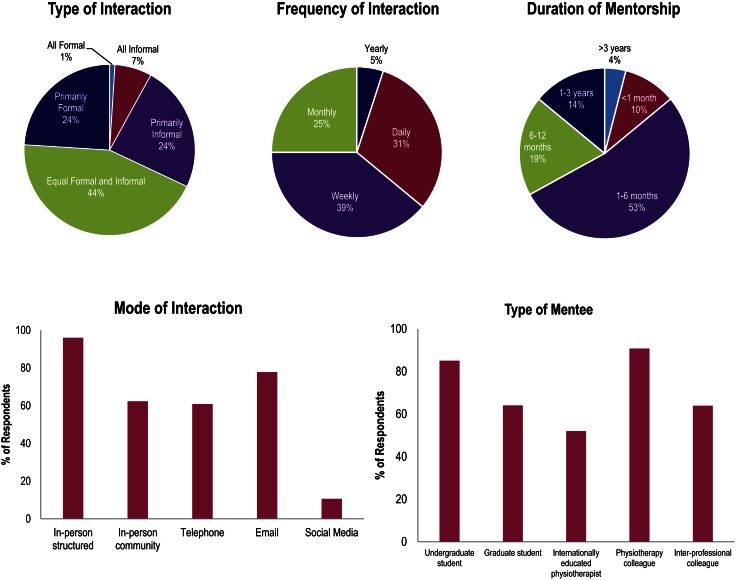

The nature of reported mentorship relationships is summarized in Figure 1. The majority of respondents reported being a mentor to fellow PT colleagues (91%). A large proportion of respondents also reported being a mentor to students, with 85% and 64% mentoring undergraduate and graduate students, respectively. Many also reported mentoring inter-professional colleagues (64%). Mentorship relationships typically lasted 1–6 months. The most commonly reported methods of interaction with mentees were meeting in person in a structured environment (96%) and corresponding by email (78%).

Figure 1.

The nature of mentorship among Canadian physiotherapy mentors (n=302).

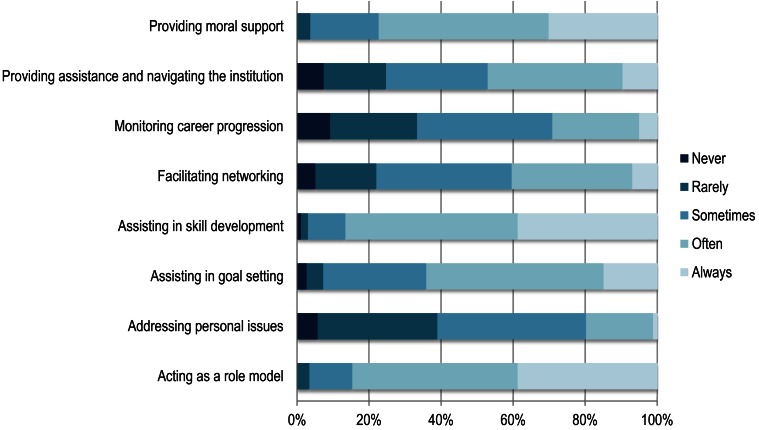

The extent of reported mentorship relationships is shown in Figure 2. Mentors reported that they most often engaged in providing moral support, assisting in skill development, and acting as a role model.

Figure 2.

The extent of mentorship: self-reported components of mentorship activities engaged in by Canadian physiotherapy mentors (n=301).

Facilitators, barriers, and benefits

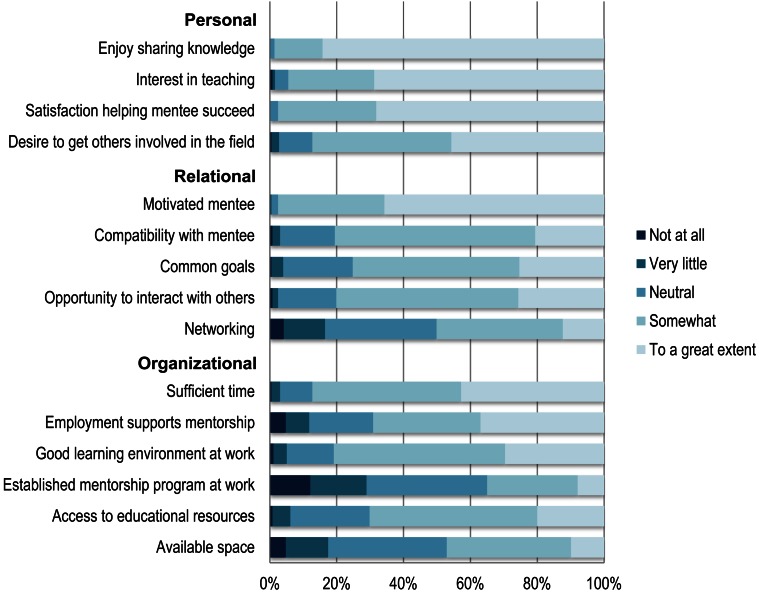

Respondents identified the majority of the items listed in Figure 3 as facilitating their ability to mentor. More than 70% identified 11 of the 15 items to be a facilitator “somewhat” or “to a great extent.” In particular, “Enjoy sharing knowledge” (98%), “Interest in teaching” (94%), “Satisfaction helping mentee succeed” (96%), and “Motivated mentee” (97%) were reported as the most prevalent facilitators of mentorship.

Figure 3.

Perceived facilitators of mentorship from the perspective of Canadian physiotherapy mentors (n=299).

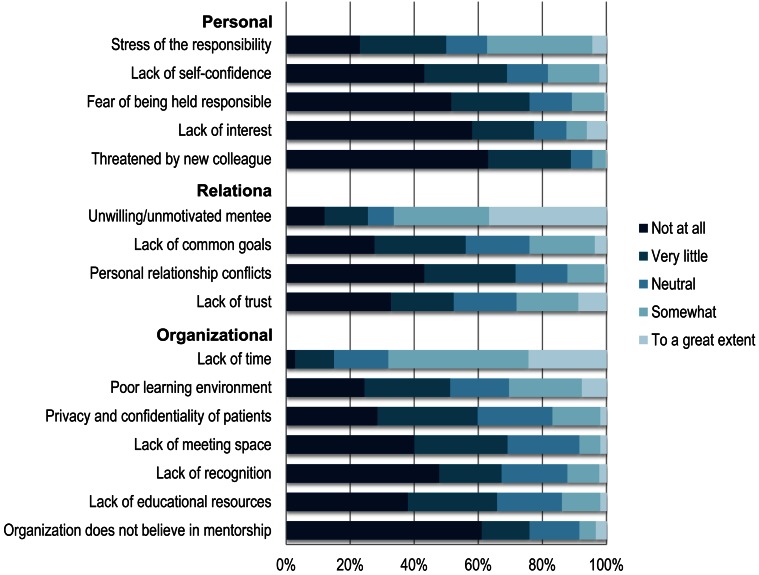

Respondents generally reported that barriers to mentorship had minimal impact on their ability to mentor (see Figure 4). Of 16 items, 13 were identified to be a barrier “very little” or “not at all” by more than 50% of the respondents. “Lack of time” (67%) and “Unwilling/unmotivated mentee” (65%) were the top barriers to mentorship.

Figure 4.

Perceived barriers to mentorship from the perspective of Canadian physiotherapy mentors (n=295).

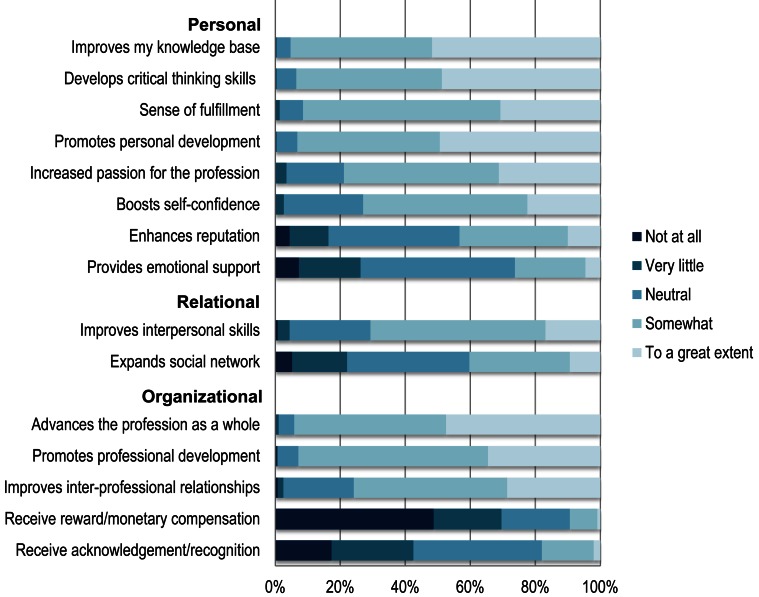

Mentors perceived a variety of items to be benefits of mentorship (see Figure 5). Out of 15 items, 10 were identified as a benefit of mentoring “somewhat” or “to a great extent” by more than 70% of the respondents. The following were the most commonly reported benefits and were comparable in ranking: “Improves my knowledge base” (93%), “Develops critical thinking skills” (92%), “Advances the profession as a whole” (92%), “Sense of fulfillment” (89%), “Promotes professional development” (91%), and “Promotes personal development” (91%).

Figure 5.

Perceived benefits of mentorship among Canadian physiotherapy mentors (n=295).

Discussion

Our study explored the concept of mentorship from the perspective of PT mentors in Canada. The demographic characteristics of the participants align with the current demographics of the Canadian PT workforce, in which the majority of physiotherapists are female (74%), hold a baccalaureate degree (57%), and work in the area of orthopaedics (69%).23

We found notable variations in the nature and extent of mentorship practices reported. The type of mentorship interaction was comparably divided among formal, informal, and a combination of formal and informal interactions. Similarly, the frequency of interaction was a near-even split among daily, weekly, and monthly interactions. When asked about the mode of interaction with mentees, mentors often reported more than one method of communication, including in person, over the telephone, or by email. We should note that, for the purposes of this survey, respondents were prompted to reflect on both previous and current mentorship experiences, but a specific timeline was not specified; as a result, the findings may not reflect the current reality of mentorship relationships.

The literature contains little guiding evidence to determine the most appropriate method of mentor–mentee interactions. For instance, although Carthas and McDonnell24 found a formal mentorship program with a predetermined duration to be successful in an acute care setting, other studies25,26 have indicated the importance of having a more flexible form of interaction. Furthermore, the distinction between formal and informal mentorship may not always be clear. Sambunjak and colleagues27 noted that if formal relationships are successful, they will develop into more functional mentoring relationships that will continue to evolve in a less formal way. This suggests that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to mentorship relationships and that outcomes may be optimized by using an individualized approach to the interaction.

An overwhelming number of respondents reported being a mentor to PT colleagues. Physiotherapists often work in highly dynamic environments in a constantly evolving health care system; consequently, peer mentorship can be a valuable resource for improving knowledge and skills and ultimately achieving career success. Takeuchi and colleagues28 found that physiotherapists believed that both mentoring and being mentored are important aspects of a successful career. Mentorship is viewed as a way to improve patient outcomes by providing a positive environment in which effective discussions regarding clinical decisions can take place.28 Similarly, a mentorship program for newly hired physiotherapists allowed them to cultivate individual skills while also enforcing the standards of the institution, leading to new therapists making fewer errors.29 Mentorship provides physiotherapists with continued opportunities for growth and development throughout their career.30 Regardless of career stage, engaging in mentorship interactions with colleagues who have a greater or different breadth of knowledge and experience will always be of immense value.31,32

For the purposes of this survey, we used a broad and all-encompassing definition of mentorship to capture the responses and perceptions of all individuals who self-identified as mentors. We did not want to either confuse or bias potential respondents by introducing terms that were not the focus of our survey (i.e., preceptor). Furthermore, although the terms mentor and preceptor are not synonymous, we recognize that the roles may not be mutually exclusive. For example, a preceptor who evaluates a student may also act as his or her mentor by facilitating the student's clinical and professional development, either during or after the predetermined period of evaluation. When a respondent chose the options “undergraduate student” and “graduate student” in response to being asked whom they have mentored, the underlying assumption was that the respondent was referring to a mentorship relationship and not preceptorship. Likewise, when asked to determine the extent to which a mentorship relationship was formal or informal, we assumed that the respondent was considering only relationships in which he or she acted as a mentor and not as a preceptor.

However, despite key differences, survey respondents may have perceived mentorship and preceptorship as interchangeable, reflecting similar confusion in practice.7,9 The majority of respondents reported being a mentor to students, and the most commonly reported mentorship duration was 1–6 months; this would capture the time frame of standard clinical internships in Canadian entry-level programmes. The high percentage of respondents selecting undergraduate mentees may reflect participants' experiences from a time when the entry-level PT degree was an undergraduate degree. Alternatively, it may also reflect the mentorship of undergraduate students contemplating a career in PT. Furthermore, “Monitoring career progression” was the second-lowest activity reported (29%), which may reflect the inherent lack of follow-up after an internship.

Although a mentor–mentee relationship is focused on progress and can flourish when it is sustained in the long term,7,9,14–16 a preceptor–student relationship can be characterized as a task-oriented, formal, and short-term arrangement with an evaluative component. Preceptorship does not require the same degree of compatibility, dedication, and investment as a mentorship relationship, and the two concepts should not be considered equivalent.7,9,14–16 Nevertheless, a preceptorship may be the most accessible way for students and individuals entering professional practice to find a mentor. A way to facilitate better mentorship experiences may be to modify the internship matching process during entry-level programmes. A system that encourages more compatible preceptor–student pairs may help establish natural and longer term mentor–mentee relationships.

Overall, mentors in PT identified many factors that facilitated mentorship, and they perceived it to be beneficial. On a personal level, their interest in sharing knowledge, teaching, and helping mentees succeed were facilitators of mentorship. Having a motivated mentee and sufficient time to mentor were the most commonly reported facilitators on the relational and organizational levels, respectively. In contrast, very few factors were considered to be barriers to mentorship; the main factors identified were an unwilling or unmotivated mentee and a lack of time.

These findings concur with the existing literature on mentors in various health care professions and their perceived facilitators of and barriers to mentorship.33–36 They also provide useful insight for supporting current mentorship practices in PT. For instance, individuals looking for a rewarding mentorship experience should look for a motivated mentee with whom they share an underlying compatibility and common goals. On an organizational level, institutions can facilitate successful mentorships by allocating time for mentorship and professional development and creating a supportive environment that is conducive to mentorship.

Respondents conveyed that there is much to be gained from participating in a successful mentorship relationship, echoing current literature findings.28,37 In nursing, structured mentorship programmes are used as a deliberate strategy to optimize the recruitment, training, and retention of experienced nurses in an institution.5 They have been shown to be a cost-effective approach to enhancing job satisfaction and promoting nurses' personal and professional growth.32 Similarly, participants in a PT mentorship program in an academic medical centre agreed that the program created a supportive work environment, improved clinical decision making and quality of care, and helped retain staff.24 In the future, more organized mentorship initiatives by PT professional associations will be invaluable for practising clinicians, their respective institutions, and the PT profession as a whole.

There is a general lack of documented information in PT regarding mentorship practices. One known example of a structured mentorship program is one that was introduced by the CPA; however, enrolment was poor.38 Although the reasons for this lack are not clear, future mentorship programmes should consider all potential factors involved and build flexibility into their design. For example, studies in medicine have suggested that a mentor–mentee matching process that is natural, flexible, and engaging is likely to facilitate more meaningful relationships.25,26 However, randomly assigned pairs are likely to experience less relational comfort, poor communication, and ultimately a less beneficial interaction.39,40 More evidence is needed to examine the characteristics of successful mentorship programmes in PT.

Our study serves as a foundation for future studies in the field. One suggestion would be to conduct intervention studies examining the effects of PT mentorship programmes, which may provide direct strategies for improving the outcome of future initiatives. Furthermore, investigating the perspectives of physiotherapists who do not engage in mentorship relationships may better highlight existing barriers and help optimize mentorship practices in the profession.

Our study had several limitations. For example, the Web-based study design and recruitment strategy precluded calculating an accurate response rate. The study was further challenged by the lack of evidence about the prevalence of mentorship in PT in Canada. As a result, we were unable to estimate the size of our target population with reasonable certainty. It was also difficult to ascertain the degree to which our study sample was representative of PT mentors in Canada.

Another source of limitation was response bias; respondents likely had more interest in mentorship than did non-respondents, which would have contributed to the overestimation of facilitators and benefits and the underestimation of barriers to mentorship. However, the support for mentorship expressed by our respondents was similar to that documented in published work in PT and other fields.28–30,35,36

Our questionnaire design also had some limitations. In question 18, for example, we asked respondents how often they consciously engaged in acting as a role model. However, whether one is a role model or not may be a judgment that can only be made by a person who sees another as someone whose behaviour he or she wants to model. Moreover, respondents were not asked whether they had been mentees themselves, which may have had a bearing on the likelihood of their becoming a mentor. However, respondents may have considered previous experiences when selecting facilitators to mentorship—for example, a positive experience as a mentee may have sparked an interest in teaching and supervision.

The inability to distinguish between mentorship and preceptorship also presents a potential limitation of our survey because it did not define the difference. We were also limited in our ability to compare findings from respondents who indicated that they had mentored students versus those who had mentored colleagues because of the significant overlap between these two groups. (Only 13 participants indicated that they had mentored only colleagues.) Future studies should be careful to distinguish these relationships to better understand the role that each plays in professional development.

Conclusion

This study provides novel evidence about the experience of mentorship from the perspective of mentors in PT profession in Canada. Our findings highlight the positive aspects of mentorship and its potential role in advancing PT, but they also underscore the continued need for support from professional associations, institutions, and physiotherapists to improve current mentorship experiences. It is our hope that this study will become the impetus for such initiatives, both in the clinical realm and in future research in the field.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

Current evidence supports the importance of mentorship in facilitating the future success of mentees in terms of productivity,4 greater career satisfaction,5 better preparation for making career decisions,6 networking in a profession,4 and helping to manage stress.7,8 However, most of the evidence is focused on the mentee; information from the mentor's perspective is limited. Furthermore, although mentorship is valued in PT, there is a dearth of evidence about its practice, and little is known about the topic from a research perspective.13

What this study adds

This is the first study to explore the concept of mentorship from the perspective of PT mentors in Canada. They reported a wealth of positivity relating to mentorship relationships and the role of mentorship in advancing the PT profession as a whole. By objectively measuring the facilitators, barriers, and benefits of mentorship from the mentor's perspective, our study can help shape future mentorship programmes to improve enrolment and outcomes.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Owens BH, Herrick CA, Kelley JA. A prearranged mentorship program: can it work long distance? J Prof Nurs. 1998;14(2):78–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S8755-7223(98)80034-3. Medline:9549209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yonge O, Billay D, Myrick F, et al. Preceptorship and mentorship: not merely a matter of semantics. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2007;4(1):e19 http://dx.doi.org/10.2202/1548-923X.1384. Medline:18052917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lafleur AK, White BJ. Appreciating mentorship: the benefits of being a mentor. Prof Case Manag. 2010;15(6):305–11, quiz 312–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181eae464. Medline:21057294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Straus SE, Sackett DL. Mentorship in academic medicine. London: BMJ Books; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Block LM, Claffey C, Korow MK, et al. The value of mentorship within nursing organizations. Nurs Forum. 2005;40(4):134–40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2005.00026.x. Medline:16371124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmoll BJ, Bohannon RW. More on mentorship. Phys Ther. 1986;66(2):272 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerhart LA. Mentorship: a new strategy to invest in the capital of novice nurse practitioners. Nurse Lead. 2012;10(3):51–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2011.09.011 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sprengel AD, Job L. Reducing student anxiety by using clinical peer mentoring with beginning nursing students. Nurse Educ. 2004;29(6):246–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006223-200411000-00010. Medline:15586121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andrews M, Wallis M. Mentorship in nursing: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(1):201–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00884.x. Medline:10064300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen CM, Lou MF. The effectiveness and application of mentorship programmes for recently registered nurses: a systematic review. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(4):433–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12102. Medline:23848442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McKenna AM, Straus SE. Charting a professional course: a review of mentorship in medicine. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(2):109–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2010.07.005. Medline:21292186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrison R, McClean S, Lawton R, et al. Mentorship for newly appointed physicians: a strategy for enhancing patient safety? J Patient Saf. 2014;10(3):159–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0b013e31829e4b7e. Medline:24583961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Quesnel M, King J, Guilcher S, et al. The knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Canadian Master of Physical Therapy students regarding peer mentorship. Physiother Can. 2012;64(1):65–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2011-02. Medline:23277687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canadian Nurses Association. Achieving excellence in professional practice: a guide to preceptorship and mentoring [Internet]. Ottawa: The Association; 2004. [cited 2014 Sept 24]. Available from: http://files.upei.ca/nursing/cna_guide_to_preceptorship_and_mentoring.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daloz LA. Effective teaching and mentoring: realizing the transformational power of adult learning experiences. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jotkowitz AB, Clarfield AM. Mentoring in internal medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):399–401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2006.05.001. Medline:16962945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. College of Physiotherapists of Manitoba. Mentorship program [Internet]. Winnipeg: The College; 2014. [cited 2014 Sept 25]. Available from: http://www.manitobaphysio.com/for-physiotherapists/mentorship-program [Google Scholar]

- 18. Newfoundland and Labrador College of Physiotherapists. Mentorship program [Internet]. St. John's: The College; 2011. [cited 2014 Sept 25]. Available from: http://nlcpt.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Mentorship-program-11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nova Scotia College of Physiotherapists. Guidelines for sponsoring physiotherapists [Internet]. Smiths Cove (NS): The College; 2004. [cited 2014 Sept 25]. Available from: http://nsphysio.com/resources/Sponsor+GUIDELINES+2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dillman D. Mail and Internet surveys: the tailored design method. 2nd ed. New Jersey: John Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jette DU, Bacon K, Batty C, et al. Evidence-based practice: beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors of physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2003;83(9):786–805. Medline:12940766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salbach NM, Jaglal SB, Korner-Bitensky N, et al. Practitioner and organizational barriers to evidence-based practice of physical therapists for people with stroke. Phys Ther. 2007;87(10):1284–303. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20070040. Medline:17684088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Canadian Institutes for Health Information. Physiotherapists in Canada, 2011 [Internet]. Ottawa: The Institutes; 2011. [cited 2015 Nov 30]. Available from: www.cihi.ca/en/ptdb2011_provincial_prof_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carthas S, McDonnell B. The development of a physical therapy mentorship program in acute care. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2013;4(2):84 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Soklaridis S, López J, Charach N, et al. Developing a mentorship program for psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):10–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0163-2. Medline:24903129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flint JH, Jahangir AA, Browner BD, et al. The value of mentorship in orthopaedic surgery resident education: the residents' perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(4):1017–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.00934. Medline:19339590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. Medline:16954490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takeuchi R, O'Brien MM, Ormond KB, et al. “Moving forward”: success from a physiotherapist's point of view. Physiother Can. 2008;60(1):19–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/physio/60/1/19. Medline:20145739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Conrad S. From novice clinician to autonomous practitioner. Perspect Mag; 2012. p. 16–8 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bohannon RW. Mentorship: a relationship important to professional development. A special communication. Phys Ther. 1985;65(6):920–3. Medline:4001172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sydenham G. Enid Graham memorial lecture 1990. Idealism to burnout: bridging the gap. Physiother Can. 1990;42(5):223–9. Medline:10107859 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greene MT, Puetzer M. The value of mentoring: a strategic approach to retention and recruitment. J Nurs Care Qual. 2002;17(1):63–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001786-200210000-00008. Medline:12369749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalén S, Hult H, et al. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(2):148–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01421590903196995. Medline:20163231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Straus SE, Chatur F, Taylor M. Issues in the mentor-mentee relationship in academic medicine: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):135–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819301ab. Medline:19116493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilkes Z. The student-mentor relationship: a review of the literature. Nurs Stand. 2006;20(37):42–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.7748/ns.20.37.42.s55. Medline:16764399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heale R, Mossey S, Lafoley B, et al. Identification of facilitators and barriers to the role of a mentor in the clinical setting. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(4):369–79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13561820902892871. Medline:19517286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ezzat AM, Maly MR. Building passion develops meaningful mentoring relationships among Canadian physiotherapists. Physiother Can. 2012;64(1):77–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2011-07. Medline:23277688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blyth T. Telephone conversation with: Andrea McAllister (Canadian Physiotherapy Association Membership Services). 2008. June 10.

- 39. Johnson BW. The intentional mentor: strategies and guidelines for the practice of mentoring. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2002;33(1):88–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.33.1.88 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cesa IL, Fraser SC. A method for encouraging the development of good mentor-protégé relationships. Teach Psychol. 1989;16(3):125–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top1603_5 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.