Abstract

Objective

Evidence indicates that children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) experience acute and prolonged academic impairment and underachievement including marked difficulty with completing homework. This study is the first to examine the effects of behavioral, psychostimulant, and combined treatments on homework problems, which have been shown to predict academic performance longitudinally.

Method

Children with ADHD (ages 5-12, N = 75, 71% male, 83% Hispanic/Latino) and their families were randomly assigned to either behavioral treatment (homework-focused parent training and a daily report card; BPT+DRC) or a waitlist control group. Children also participated in a concurrent psychostimulant crossover trial conducted in a summer treatment program. Children's objective homework completion and accuracy were measured as well as parent-reported child homework behaviors and parenting skills.

Results

BPT+DRC had large effects on objective measures of homework completion and accuracy (Cohen's ds from 1.40, to 2.21, ps < .001). Other findings, including unimodal medication and incremental combined treatment benefits, were not significant.

Conclusions

Behavioral treatment focused on homework problems results in clear benefits for children's homework completion and accuracy (the difference between passing failing, on average) whereas long-acting stimulant medication resulted in limited and largely non-significant acute effects on homework performance.

Keywords: ADHD, behavioral treatment, psychostimulants, parent training

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (Nigg & Barkley, 2014). Prevalence rates are estimated at around 11% (CDC, 2011), making ADHD the most common mental health disorder among children. Children with ADHD experience widespread, severe functional impairments across social, academic, and behavioral domains throughout development and into adulthood (Faraone, Biederman, & Mick, 2006; Sibley et al., 2012). Further, ADHD is a major public health concern and is associated with very high societal, familial, and individual costs (Pelham, Foster, & Robb, 2007; Robb et al., 2011).

One of the most impairing aspects of childhood ADHD is the robust relation with prolonged academic underachievement (Frazier, Youngstrom, Glutting, & Watkins, 2007; Loe & Feldman, 2007; Molina et al., 2009; Polderman, Boomsma, Bartels, Verhulst, & Huizink, 2010). Elementary aged children with ADHD have severe academic problems characterized by lower seatwork completion, seatwork accuracy, on-task behavior, and homework performance than their peers (Atkins, Pelham, & Licht, 1985; Mautone, Marshall, Costigan, Clarke, & Power, 2012; Power, Werba, Watkins, Angelucci, & Eiraldi, 2006). Problems continue into later school years as individuals with ADHD in middle and high school have poorer organizational skills, lower report card grades, higher truancy, and higher rates of suspension and grade retention than their peers (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2006; Kent et al., 2011; Molina et al., 2009; Robb et al., 2011). Further, significantly fewer individuals with ADHD graduate from high school (68% vs. 100% of controls; Barkley et al., 2006) or enroll in four year colleges and universities than controls (29.5% vs. 76.8% of controls; Kuriyan et al., 2013).

Effective treatment options focused on academic functioning for children with ADHD are of critical importance. Much work has been done evaluating the effects of the three evidence-based treatments for ADHD, stimulant medication, behavioral treatment, and their combination, on academic impairment within school and analog settings. The most widely used evidence based treatment for children with ADHD, psychostimulants (Visser et al., 2014), has been shown to produce consistent acute improvements across studies in seatwork completion, disruptive behavior, and on-task behavior in the classroom (Conners, 2002; Pelham et al., 2001). However, existing research shows that these acute salutary effects of stimulants on daily seatwork productivity do not translate into long-term academic gains (Brak & Brak, 2011; Langberg & Becker, 2012; Loe & Feldman, 2007; Molina et al., 2009), which, in conjunction with the high proportion of children with ADHD who receive stimulant medication as the sole treatment (69% currently medicated; Visser et al., 2014), highlights the importance of researching psychosocial/psychoeducational methods to improve educational outcomes for children with ADHD.

The primary psychosocial evidence-based treatment for ADHD, behavioral modification, consists of classroom management and/or behavioral consultation in the school setting (Evans, Owens, & Bunford, 2014; Pelham, Wheeler, & Chronis, 1998; Pelham & Fabiano, 2008). Classroom management procedures and interventions, including skills such as setting clear limits and rules, providing contingent positive reinforcement, and using a Daily Report Card (DRC; Dupaul, Eckert, & Vilardo, 2012; Fabiano et al., 2010; Volpe & Fabiano, 2013), have produced short-term improvements in classroom behavior and seatwork completion and accuracy among children with ADHD in classroom and analog classroom settings (Dupaul et al., 2012; Fabiano et al., 2007, 2009). Combined stimulant and behavioral treatment also leads to improved functioning in the school setting and provides additional benefits. In analog classroom settings, combined treatment at low to moderate doses of each component results in incremental improvements in seatwork completion and classroom behavior, yielding larger effects than either treatment alone (Fabiano et al., 2007; Pelham et al., 1993, 2005). Further, combining treatments allows for lower doses of each individual treatment than would be needed for either treatment to produce similar beneficial effects (Fabiano et al., 2007; Pelham et al., 2014). This is critical due to the potential expense of “high doses” of behavioral treatment and the increased side effects at higher doses of stimulant medication.

Though direct intervention in the school is warranted for all children with ADHD, it is potentially advantageous to explore additional ways to intervene around the academic functioning of children with ADHD, such as at the home or parenting level. One underdeveloped area of research is the effect of interventions targeting homework success among children with ADHD across settings. The homework process, as a whole, is abundant with steps that can be especially difficult for a child with ADHD to complete, such as writing down assignments, remembering to bring materials home, sitting down to complete assignments, continuing to work despite a distracting home environment, sustaining effort until work is complete, and remembering to turn in assignments the next day. In fact, children with ADHD exhibit more severe homework problems than typically developing peers (Epstein et al., 1993, Power et al., 2006), supporting the importance of homework performance as a treatment target and pathway to academic improvement. Though the literature is mixed, studies tend to indicate that, in the general population, homework is positively related to achievement and that the relation is stronger in the middle school and high school (Cooper, Robinson, & Patall, 2006). However, longitudinal studies show that homework performance in elementary school is a key predictor of later academic success among individuals with ADHD (Langberg et al., 2011),

The impact of stimulants on homework functioning has rarely been evaluated in a controlled study, and available findings are mixed. When comparing naturalistically defined groups of medicated and unmedicated children with ADHD, no significant differences in homework performance (% accuracy) or parent and teacher reported homework problems have been found (Mautone et al., 2012). Evans and colleagues (2001) conducted the only study to date manipulating stimulant dose to examine effects on homework. The study was conducted among adolescents with ADHD in a controlled setting (the Summer Treatment Program; STP), and results indicate a small, significant effect of short-acting methylphenidate (MPH) on homework completion in response to the highest late afternoon dose of MPH (15mg; Cohen's d = 0.35).

Evidence-based behavioral treatments, such as behavioral parent training (BPT), are well poised to affect educational outcomes due to their inherent flexibility to target specific problem behaviors in the settings where they occur. Interventions containing a psychosocial component show larger effects on homework problems than interventions lacking that component, and significant improvements are sustained two years post-treatment (Langberg et al., 2010). Given the positive impact of parental involvement on student motivation and achievement in the general population (Englund, Luckner, Whaley, & Egeland, 2004; Gonzalez-Dehass, Willems, & Holbein, 2005; Jeynes, 2005), BPT interventions focused on homework problems and facilitating school-home communication may be particularly helpful in improving the academic achievement and performance of children with ADHD.

Within the extensive array of BPT programs for children with ADHD, two programs have been developed that target homework functioning: 1) Family School Success Program (FSS; Power, Karustis, and Habboushe, 2001) and 2) Parents and Teachers Helping Kids Organize (PATHKO; Abikoff et al., 2013). Both programs include many efficacious components of BPT (i.e., consistent responding, time out, goal setting, rewards, and positive attention; Kaminski et al., 2008) and have demonstrated efficacy in improving parent-reported problem behaviors during homework time, with moderate to large effect sizes ranging from .52 to 1.51 (Abikoff et al., 2013; Power et al., 2012). Further, these academic-focused BPTs improved self-reported parenting strategies, teacher reported homework problems, and parent and teacher reported organizational skills. Interestingly, children who happened to be on stimulant medication and received BPT showed greater improvement on parent reported homework management than their unmedicated peers (Power et al., 2012). However, medication was not controlled or manipulated in this study, and objective measures of homework completion and accuracy were not utilized. No rigorously controlled trials to date have investigated the effect of behavioral treatment, psychostimulant treatment, and their combination on homework performance among children with ADHD.

The current efficacy study aims to address this gap by evaluating single and combined treatment effects in a highly controlled Summer Treatment Program (STP). The STP setting allows for the systematic evaluation of treatment effects on objective measures of homework completion and accuracy in addition to parent-reported problems, which expands further on the current literature. We hypothesize that both behavioral and medication treatments will produce benefits on child homework performance. Additionally, we hypothesize that combined treatment will produce improvements in homework performance beyond that of either unimodal treatment.

Method

Participants

Seventy-five children ages 5 to 12 years (mean age = 7.97 years, SD = 1.71) who were treated in the STP and enrolled in a larger clinical trial to evaluate tolerance to stimulant medication (MH099030) participated in the current study. All participants met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ADHD (77% combined presentation, 20% predominantly inattentive presentation, 3% predominantly hyperactive/impulsive presentation). As is standard in the field, symptoms were considered present if either the parent or teacher endorsed the symptom on the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBD; Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992) or a parent structured clinical interview (DISC IV; Shaffer, Fisher, & Lucas, 1998) and impairment was reported on the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS; Fabiano et al., 2006; Pelham, Fabiano, & Massetti, 2005). Additionally, 58% of participants met criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and 12% met criteria for Conduct Disorder. Participants were predominantly male (71%) and of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (83%). In terms of child race, 89% of the sample identified as white, 15% as black, and 1% as American Indian or Alaska Native (categories were not mutually exclusive). Median family income was 48,000 dollars, and average family income was largely skewed by two families earning near 500,000 per year (M = 75,025, SD = 85,887). Table 1 includes additional demographic information.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for participant characteristics.

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 8.00 | 1.70 |

| Estimated Full Scale IQa | 95.51 | 12.35 |

| DSM 5 items endorsed by parents or teachersb | ||

| Inattention | 8.32 | 1.105 |

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity | 7.41 | 2.04 |

| Oppositional/defiant | 4.68 | 2.84 |

| Conduct disorder | 1.12 | 1.71 |

| IOWA Conners Parent Rating Scale Inattention/Overactivityc | 10.70 | 3.10 |

| IOWA Conners Parent Rating Scale Oppositional/Defiantc | 7.36 | 3.90 |

| IOWA Conners Teacher Rating Scale Inattention/Overactivityc | 10.21 | 3.18 |

| IOWA Conners Teacher Rating Scale Oppositional/Defiantc | 6.06 | 4.68 |

| Parent age | 39.62 | 6.81 |

| Parent marital status (% single)d | 51.9% |

Note.

Full Scale IQ was estimated from the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence- Second Edition. For children younger than 6 years old at intake, the Block Design and Vocabulary subscales from the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence - Fourth Edition.

A symptom was considered present if either the teacher or parent rated it as clinically significant (endorsed as ‘pretty much’ or ‘very much’) on the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, and Milich, 1992) or on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; 1998).

Single includes primary caregivers who were never married, divorced, and separated and does not include those who were married or living with a partner.

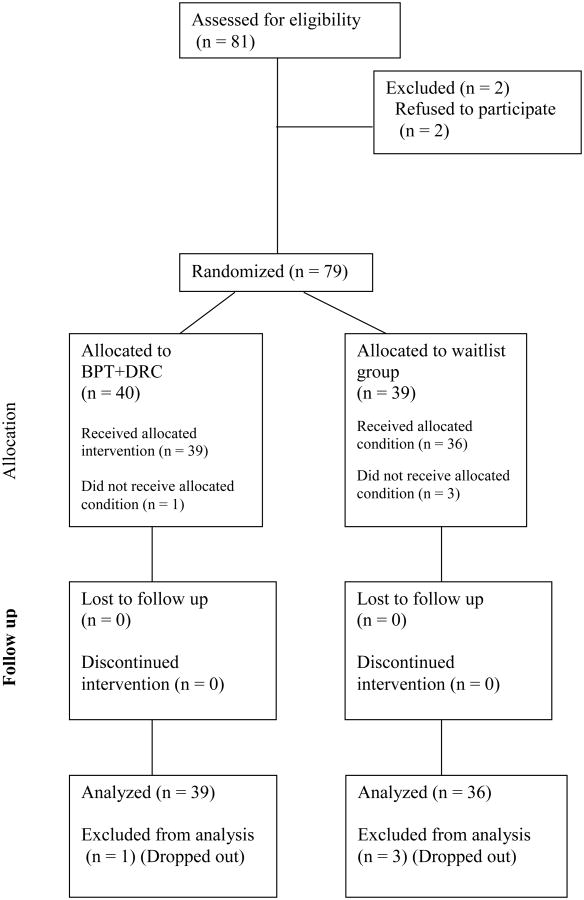

Children were excluded from the study if they had an estimated Full-Scale IQ below 80, had a previous diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (or if parents, teachers, or clinicians observed or reported behaviors consistent with Autism, additional measures were administered), were currently receiving psychotropic medications for conditions other than ADHD, had conditions that could be made worse by stimulant medication (e.g., sustained, severe tics), or had documented intolerability or lack of response to stimulant medication (as evidenced by worsened or not improved symptoms on checklists). Initially, 79 children were randomized to either the behavioral treatment (BPT+DRC) or waitlist control (WL; who received BPT in the fall following the STP) resulting in 40 children being assigned to BPT+DRC and 39 to the WL group. All children were also involved in a three-week double-blind placebo/medication crossover (described below). Collectively, treatment allocation allowed us to conduct analyses across four conditions (i.e., no intervention, medication only, BPT+DRC only, and combined intervention) regarding the effect of behavioral and stimulant treatment on homework. Four children (see Figure 1) were not included in analyses as they dropped out prior to baseline data collection and did not receive their assigned treatment.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participation from consent through to data analysis. BPT+DRC = Homework-focused behavioral parent training and a homework completion target on the DRC.

Research Design

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and participants completed consent and assent forms. The children in this study attended the STP from 8am to 5pm, 5 days per week, for 8 consecutive weeks. The STP is an evidence-based, comprehensive behavioral treatment for ADHD that includes a point system, contingent rewards, and social reinforcement for appropriate behavior (Evans, Owens, & Bunford, 2014; Fabiano, Schatz, & Pelham, 2014; Pelham & Fabiano, 2008). Children spent seven hours per day in recreational settings and two hours per day in an analog classroom setting (divided into two periods). Homework was assigned by teachers in the afternoon classroom and collected in the morning classroom the following day.

The STP setting allowed for systematic control of the homework assigned. Multiple sources of information were used to determine the appropriate grade level and the amount of homework that should be assigned to each child. Grade level was determined by evaluating children's grade equivalencies on achievement testing (Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-3rd Edition: Numerical Operations and Word Reading subtests) in combination with the STP teacher's input on the feasibility of assignments for each child. The amount of homework assigned was based on nationally representative average teacher expectations for the amount of time children should spend doing homework, separately reported for Math and Reading/Language Arts and for 1st, 3rd, and 5th grade (RLA; see U.S. Department of Education, 2008), with average time expectations for RLA and Math combined varying from 25 to 60 minutes each night across 1st to 5th grade. To apply this information to each child, children were timed completing homework assignments in the classroom (during the first two weeks of the STP), and STP teachers were consulted. On Monday through Thursday each week, children were typically assigned 2-4 mathematics worksheets and 1-3 short reading comprehension assignments depending on the child's grade level and the time they took to complete assignments, as described above.

Intervention

Medication

Children underwent a 2-week titration period during which they were randomly assigned to receive three different doses of once-daily, extended-release MPH (Concerta 18, 27, and 36 mg, except for 10 children who received comparable doses of Focalin XR). The lowest dose that produced substantive or incremental efficacy with minimal side effects during the two-week titration was administered during a subsequent medication crossover. Children were randomly assigned to receive medication or placebo for three consecutive weeks, including weekends, and the crossover condition for the final three weeks of the STP. Children were prescribed an average daily dose of 21 mg (SD = 7.8), or .70 mg/kg/day (SD = .25). Most children (66.7%) received 18mg Concerta, 5mg Focalin XR, or 10mg of Daytrana, 24% received 27mg of Concerta, 8% received 36mg of Concerta or 10mg of Focalin XR, and 1.3% (one child) received 54mg of Concerta.

Behavioral Treatment

Families were randomly assigned to either the homework-focused behavioral intervention (BPT+DRC) or a waitlist control group (WL). BPT+DRC was a behavioral treatment package largely based on Power's work developing the FSS and the Homework Success Program (HSP; Power, Karustis, & Habboushe, 2001) as well as general parent training content from the Community Parent Education Program (COPE; Cunningham, Bremner, & Boyle, 1995; Cunningham, 1990) and a DRC. The HSP manual was used for all homework-focused sessions and within-session content (e.g., homework routine, when-then contingencies, homework goals). The more general parent training skills (e.g., positive attention, time out) in the current intervention were derived from COPE, the standard BPT program employed in the STP (see Table 2 for outline of session content). In the COPE style of parent training, families sit in small subgroups of about seven parents each, watch video-taped vignettes of parenting errors, and discuss parenting errors, alternative strategies, potential barriers, and benefits of strategies. After each discussion, parent subgroup leaders report back to the larger group, and BPT clinicians facilitate discussion by reflecting questions back to the group and modeling proposed strategies. Due to the predominantly Hispanic sample, subgroup language could be either English or Spanish, and a Spanish-speaking translator was present in each of the parent training sessions.

Table 2. Behavioral Parent Training Session Descriptions.

| Session Title | Session Content and Goals |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction to Program | Social learning theory |

| 2. House Rules and Positive Attention | Develop house rules with family |

| Learn about positive attending through discussion and video modeling | |

| 3. Homework Routine and Planned Ignoring | Develop a homework routine |

| Learn about when-then statements in the context of homework time | |

| Learn about planned ignoring through discussion and video modeling | |

| 4. Managing Time and Setting Goals | Establish use of homework Daily Report Card (DRC) |

| Ensuring reward menu is motivating and modifying as needed | |

| 5. Managing Time and Setting Goals 2 and Time Out | Review use of homework DRC and problem solve around issues |

| Introduce Time-Out as an alternative punishment strategy for severe behaviors | |

| 6. Home Daily Report Card | Integrate homework DRC with overarching home DRC |

| 7. Individual Session | Review and modify each family's individualized homework plan |

| Problem-solve around homework goals, problem behaviors, and motivating rewards |

BPT+DRC consisted of six, two-hour group sessions were completed in the evenings during the first two weeks of the STP, and one 30 minute, individual session was completed during the subsequent two weeks. Group BPT sessions were facilitated by PhD-level clinicians (authors WEP and EKC) with extensive experience leading the COPE program and co-facilitated by doctoral students (BMM and ARA). Childcare was provided during all sessions. In the individual session, parents discussed individualized homework plans and behavior plans with a group facilitator and generated feasible solutions to improve parenting effectiveness and strategy use. In addition to the individualized DRC goals that were developed for each child as a standard component of the STP, all children in the BPT+DRC group, and no children in the WL group, had a goal stating ‘Completes homework with 80% accuracy.’ As described above, homework was assigned at each child's level of academic achievement, so this goal was not individualized. In the STP setting, children are often reminded of DRC goals, children earn ‘Fun Friday’ based on meeting at least 80% of their goals three days, and counselors communicate the child's success in meeting his or her goals to the parent at the end of each camp day. Daily DRC feedback was provided in Spanish if the family preferred.

Measures

Objective Measures

Homework completion (# complete / # assigned) and homework accuracy (# correct / # complete) were assessed separately for Math and Reading/Language Arts (RLA) to evaluate the efficacy of medication and behavioral treatment in improving functional, objective academic outcomes (Fabiano et al., 2007; Pelham, Gnagy, Greiner, Waschbusch, Fabiano, & Burrows-MacLean, 2010). Completion and accuracy were calculated by totaling the number of problems assigned, completed, and correct for the final week of each crossover phase (STP weeks 5 and 81), and the resulting values were used in subsequent analyses.

Parent-Report Measures

Parents completed measures at baseline, after the first three-week cross-over period, and after the final crossover. As such, parents were asked to reflect on the previous three weeks when completing forms. The Homework Problems Checklist (HPC; Anesko, Schoiock, Ramirez, & Levine, 1987) is a 20-item scale that assesses child homework performance via parent report. Research indicates consistency with coefficient alphas from .90 to .92 (Anesko et al., 1987). According to multiple factor analyses, the HPC has two factors that measure 1) Completion behaviors (i.e., problem behaviors occurring during homework time; current study α = .91) and 2) Poor materials management (i.e., problems related to bringing homework materials home and turning in assignments; current study α = .83; Langberg et al., 2010; Power, Werba, Watkins, Angelucci, & Eiraldi, 2006)2.

The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire, Negative/Ineffective Discipline Factor (APQ N/ID; Shelton, Frick, & Wooton, 1996) assesses parent-reported negative parenting strategies such as inconsistent responding and overly harsh responding to child behavior. The validity of the N/ID factor has been examined and supported by previous research (Hinshaw et al., 2000; current study α = .77). Additionally, the parent reported the time the child took the medication (M = 7:21, SD = 0:20) and completed homework (M = 18:59, SD = 1:19) daily, and this was used to calculate the variable hours since receiving medication (M = 11:27, SD = 1:56). Hours since receiving medication was used as a control variable herein as it is difficulty to interpret the effects given the low variability in time of medication ingestion and the instruction in the BPT classes to begin homework earlier.

Missing Data Handling

Missingness was low across measures (1-7%). T-tests comparing outcome variables for individuals who had missing and non-missing values did not indicate significant group differences (ps > .05; variables included IQ, ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms, age, gender, HPC and APQ baseline score, parent age, and parent income) apart from one comparison3. Findings support the assumption that data were missing at random. Item-level multiple imputation in SPSS 20 including all above variables was used to create 10 imputed datasets (Schafer, 1999). Results were pooled with PROC MI ANALYZE in SAS 9.3. Missing values for items correct indicated that completion was either missing or zero and were therefore not imputed. As homework accuracy was defined as items correct divided by items complete, computation would result in an undefined integer as a result of the denominator (completion) being zero.

Analyses

Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs; Stroup, 2012) were used to analyze both the objective measures and parent-report measures to accommodate the repeated measures design. PROC GLIMMIX was utilized for analyses of objective measures. For both Math and RLA, completion was analyzed by entering the number of problems completed as the events variable and the number of problems assigned as the trials variable producing a percentage as the outcome variable (Schabenberger, 2005). Similarly, accuracy for both Math and RLA was analyzed with number of items correct as the events variable and number of completed items as the trials variable. Sequence of medication treatment was controlled for in the model as a random effect. Further, models included the following variables as fixed effects: cross-over period, hours between taking medication and starting homework, medication status, group assignment (BPT+DRC or WL), and the interaction between treatments. Analyses controlled for interactions between cross-over period and treatment variables (Simpson & Hamer, 1999; Yarandi, 2004).

PROC MIXED was used to analyze the parent-report measures with HPC Completion Behaviors, HPC Materials Management, and APQ N/ID as the outcome variables in three separate models. Random effects were identical to the previous analyses. Fixed effects in these models included the relevant baseline score, cross-over period, medication status, BPT+DRC or WL group, the interaction between treatment variables, and interactions with cross-over period.

Results

Intervention Adherence

Parents in the BPT+DRC group attended an average of 5 of 7 total sessions (group and individual). Modal attendance was 100% of sessions, and the median attendance was 6 of 7 sessions. Of the six group sessions, 19% of families attended 1 to 3 sessions, 49% attended 4 or 5 sessions, and 32% attended all six group sessions. Attendance for the individual, booster session was 80%. Two separate BPT groups were held simultaneously, with 21 families (representing 24 children due to siblings in the study) in one group and 15 families in the second group. Based on the audiotapes of sessions, BPT clinicians implemented 94% of parent training procedures per session on average (SD = 5%), though for one session in one BPT group, the audiorecorder malfunctioned and did not record the session. Medication or placebo was taken daily (depending on the cross-over period), and parents turned in a card each morning stating the time they administered the pill.

Objective Measures

Due to the cross-over design of this study and the inclusion of cross-over period and treatment sequence covariates, we report estimated means and associated statistical tests rather than parameter estimates to aid in clear interpretation. In the text, we report main treatment effects for BPT+DRC and medication controlling for the other treatment and covariates. See Table 3 for model-estimated means for each treatment group and post-hoc comparisons.

Table 3. Estimated Means, Standard Deviations, and Effect Sizes.

| M(SD) | Cohen's d (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Objective Measures (%) | No Treatment (n=36) | Med Only (n=36) | BPT+DRC Only (n=39) | Combined (n=39) | BPT+DRC Between-Subjects | Medication Within-Subjects |

|

| ||||||

| Math Completion | 68.62 (8.22) | 73.11 (7.96) | 82.34 (6.47) a,c | 83.10 (6.37) a,c | 2.21*** (1.63, 2.79) | 0.30† (.06, .54) |

| RLA Completion | 75.31 (9.98) | 77.12 (10.11) | 84.69 (7.91) a,c | 87.86 (7.17) a,c | 1.56*** (1.04, 2.08) | 0.30† (.03, .57) |

| Math Accuracy | 83.85 (8.79) | 87.75 (7.49) a | 91.89 (5.42) a,c | 90.94 (5.55) a,c | 1.56*** (.99, 2.13) | 0.20 (-.10, .50) |

| RLA Accuracy | 82.76 (11.35) | 86.14 (10.14) | 91.59 (6.96) a,c | 90.42 (7.02) a,c | 1.40*** (.84, 1.96) | 0.09 (-.21, .39) |

| Parent Report Measures | ||||||

| HPC Completion | 16.78 (7.85) | 15.31 (7.84) | 19.24 (7.85) | 16.64 (7.85) | -0.31 (-.77, .15) | 0.26 (-.01, .53) |

| HPC Materials Management | 3.45 (3.60) | 2.99 (3.56) | 3.11 (3.57) | 3.73 (3.56) | -0.07 (-.39, .53) | -0.02 (-.24, .20) |

| APQ N/ID | 20.21 (4.65) | 20.15 (4.59) | 19.02 (4.59) | 18.24 (4.60) | 0.38 (-.08, .84) | 0.09 (-.09, .27) |

Note. This table presents estimated means and standard deviations based on the models. At the p < .05 level,

statistically superior compared to no treatment group,

statistically superior compared to BPT+DRC only,

statistically superior compared to Med only. Cohen's ds are based on estimated mean differences and describe main effects of treatment (BPT+DRC vs. WL control; Medication vs. Placebo) controlling for the other treatment and covariates,

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to accommodate for differences in between and within-subjects effect sizes (Nakagawa & Cuthill, 2007).

Homework Completion

The model analyzing Math completion indicates a non-significant effect of medication, t(114.5) = -1.83, p = .07, and a significant effect of BPT+DRC with a very large effect size (see Table 3), t(95.9) = -8.85, p < .001, in that children in the BPT+DRC group completed about 12% more Math homework than the WL group controlling for medication status. The effect of the interaction between medication and BPT+DRC on Math completion was not significant, and least square mean differences are therefore not described here (see Table 3). F-statistics for the interaction ranged from 0.27 to 2.98 (numerator df = 1, denominator df = 114), with all p-values greater than 0.054. The association between hours since receiving medication and Math completion was not significant, t(11.9) = -2.18, p = .051.

The model analyzing RLA completion similarly indicates a non-significant effect of medication, t(125.3) = -1.76, p = .08, and a significant effect of BPT+DRC, t(95.4) = -6.25, p < .001, such that children in the BPT+DRC group completed just over 10% more RLA homework than the WL group, controlling for medication. The interaction between medication and BPT was not significant, and F-statistics for the interaction ranged from 0.19 to 2.48 (numerator df = 1, denominator df = 114), with all p-values greater than 0.054. The effect of hours since receiving medication was significant, t(12.5) = -2.26, p = .04, such that less time between taking medication and starting homework was related to higher RLA homework completion.

Homework Accuracy

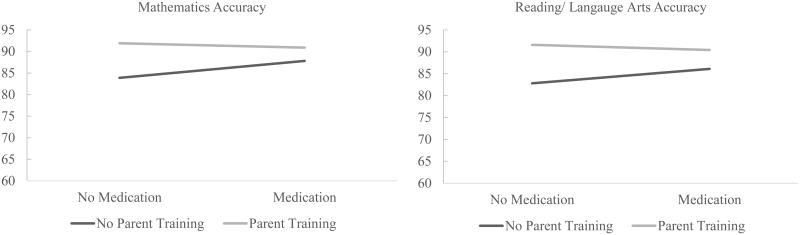

The effect of medication on Math homework accuracy was not significant, t(115) = -1.23, p = .22, and there was a significant effect of BPT+DRC, t(115) = -6.82, p < .001, indicating that children in the BPT+DRC group had about 6% higher Math homework accuracy than the WL group, controlling for medication. However, the interaction between medication and BPT+DRC was significant (see Figure 2), F(1, 115) = 7.33, p = .01. Least square mean differences between combined, unimodal, and no treatment groups on Math accuracy were explored due to the significant interaction and indicated that BPT+DRC only and combined treatment were both superior to no treatment, t(115) = -6.70, p < .001, t(115) = -5.94, p < .001, and were both superior to medication only, t(115) = -3.85, p < .001, t(115) = -2.93, p = .004, respectively. Combined treatment was not significantly better than BPT+DRC only, t(115) = 1.04, p = .30. Medication only was significantly superior to no treatment, t(115) = -2.85, p < .001, indicating that children had about 4% higher accuracy on their Math homework when receiving medication compared to the no treatment group. The effect of hours since receiving medication on Math accuracy was not significant, t(115) = 1.79, p = .08.

Figure 2.

BPT and medication interaction effects on homework accuracy.

The effect of medication on RLA homework accuracy was not significant, t(114) = -0.58, p = .56, and the effect of BPT+DRC on RLA accuracy was significant, t(114) = -6.20, p < .001, indicating that children in the BPT+DRC group had about 6% higher RLA accuracy than the WL group. However, the interaction between medication and behavioral treatment was significant (see Figure 2), F(1, 114) = 4.05, p = .047. Least square mean differences between combined, unimodal, and no treatment groups on RLA accuracy indicated that BPT+DRC only and combined treatment were both superior to no treatment, t(114) = -5.73, p < .001, t(114) = -5.00, p < .001, and were both superior to medication only, t(114) = -3.83, p < .001, t(114) = -3.00, p = .003, respectively. Combined treatment was not significantly better than BPT+DRC only, t(114) = 1.00, p = .32. There was a trend for improved RLA accuracy in the medication only group compared to no treatment, t(114) = -1.86, p = .07. The effect of hours since receiving medication on RLA accuracy was not significant, t(114) = 0.93, p = .35.

Parent-Report Measures

As stated previously, results display estimated means as opposed to parameter estimates to facilitate clear interpretation, and Table 3 contains estimated means for each treatment group. In the models predicting each of the parent-report measures (HPC Completion Behaviors, HPC Materials Management, and APQ N/ID) there was not a significant effect of medication, t(117.9) = 1.74, p = .08, t(109.6) = -0.18, p = 89, t(110.1) = 0.84, p = .40, BPT+DRC, t(116.8) = -1.28, p = .21, t(133.6) = -0.28, p = .78, t(128.6) = 1.58, p = .12, or their interaction, F(1, 71) = 0.02, p > .055, F(1, 71) = 1.16, p > .05, F(1, 71) = 0.16, p > .05, respectively. Baseline scores significantly predicted post-treatment scores in each of the models, b = 0.32, t(122.2) = 3.27, p < .001, b = 0.32, t(135.11) = 4.51, p < .001, b = 0.58, t(134.7) = 6.40, p < .001, indicating that the individual's baseline HPC Completion Behaviors, HPC Materials Management, and APQ N/ID scores were positively related to their post-treatment scores, respectively.

Discussion

This study provides the first controlled evaluation of the effect of behavioral treatment, long acting stimulant medication, and their combination on homework functioning among children with ADHD. Results indicated that 1) homework-focused BPT with a DRC component results in improved objective homework performance (completion and accuracy) among children with ADHD, 2) long-acting stimulant medication produces small and likely clinically insignificant benefits on homework accuracy only in the absence of homework-focused behavioral treatment, 3) combined behavioral treatment and medication did not produce additional benefit beyond behavioral treatment alone on objective measures of homework performance, and 4) significant treatment effects on parent-report measures were not found. Each finding and its clinical implications are now discussed in turn.

Behavioral Treatment

The BPT+DRC program implemented to improve parental management of child behavior, organization, and productivity during homework time consistently led to substantial, acute improvements in objective measures of homework completion and accuracy. The current study found that children in the homework-focused behavioral treatment group achieved 10-13% higher homework completion and 8% higher accuracy than the WL group. Considering homework completion and accuracy together, children in the BPT+DRC group achieved a ‘C’ on average (92% correct of 83% complete is a score of about 75%) whereas children who did not receive BPT+DRC and were not on medication achieved an ‘F’ on average (58% in math and 62% in RLA). Thus, receiving the BPT and DRC treatment program was the difference between passing and failing homework assignments. By influencing a critical predictor of academic success, this study replicates previous research demonstrating the efficacy of behavioral treatment in improving daily academic functioning among children with ADHD (e.g., Fabiano et al., 2007; Power et al., 2012) and expands this research by including objective homework performance.

Efficacy trials investigating similar interventions (i.e., FSS and PATHKO) indicate effect sizes varying from .52 to 1.51 on parent report measures of homework functioning. The results of the current study extend their reports by indicating compelling and meaningful benefits of behavioral treatment on objective measures of homework completion and accuracy (Cohen's ds from 1.40 – 2.26). Compared to parent ratings, objective measures are more face-valid exemplars of a child's actual performance. Though problematic behavior during homework time is a clinical concern among children with ADHD (Power et al., 2006), homework scores rather than behavior during home work are more directly related to academic success and grades at school.

Another strength of the current study is that the STP setting afforded high experimental control over the homework assigned, grading procedures, and specific intervention components, namely the individualized DRC. The DRC is an existing component of the STP, and children in the BPT+DRC group were necessarily given the DRC goal ‘completes homework with 80% accuracy’ whereas the WL group did not have this goal. At the end of each day in the STP, children, parents, and counselors review the child's progress on his or her DRC goals and discuss which contingent home reward will be earned that evening. Though the FSS study also included a DRC component, the fidelity and consistency of DRC implementation in the FSS study likely varied by each individual child's teacher and school just as the specific homework assigned and grading procedures would vary.

Overall, clinically significant, compelling benefits on objective measures of homework completion and accuracy were found for children whose families received homework-focused parent training and DRC. To the extent that a teacher incorporates homework into a child's grade in a given subject area, the behavioral intervention used herein could have a meaningful impact on the child's grades and academic performance. Improving homework functioning among children with ADHD is critical as homework problems are severe and longitudinally related to important academic outcomes such as grades in this population (Langberg et al., 2010; Langberg et al., 2011; Power et al., 2006).

Medication

Medication effects were limited and neither clinically nor academically meaningful. Despite achieving about 3-4% higher homework accuracy when receiving medication in the absence of BPT+DRC, children did not complete significantly more homework, and BPT+DRC alone was significantly superior to medication alone in all analyses of homework completion and accuracy. The results indicating a statistically non-significant medication effects on homework completion are surprising given the extensive literature documenting effects on comparable measures in the classroom (Fabiano et al., 2007; Pelham et al., 2001).

Environmental differences between home and school may be critical to explaining the lack of medication effects on homework completion despite clear effects on seatwork completion in the classroom setting. School and classwork are typically structured with clear expectations, minimal distractions, and a consistent routine. Further, a well-run classroom will include teacher monitoring, classroom rules, and individualized performance feedback. Although these same strategies are taught to parents in homework-focused BPT, it is possible that in the absence of this basic routine and structure, children aren't more likely to work on assignments when receiving medication. It is also likely that parents are less consistent than teachers in implementing routine, structure, and contingencies during academic work.

Additionally, this study may have failed to indicate a positive effect of medication due to the low doses used and the time course of Concerta. The majority of studies showing effects of medication in the classroom setting were conducted with slightly higher doses and during peak hours (i.e., when medication should have its largest effect; Fabiano et al., 2007; Pelham et al., 2001). In this study, homework performance was measured at an average of 11.5 hours post ingestion. Research on the time course of Concerta indicates that effects are clear 12 hours post-ingestion (Pelham et al., 2001). However, the average dose in that study (35mg) is considerably higher than the average dose of 21mg used in the current study, and the time courses of different doses of Concerta have not been studied. Despite this limitation, the time between medication administration and homework completion reported herein likely represents many families' experiences starting homework after school or when parents return from work. Further, doses were titrated to optimize behavioral performance and productivity in the analog classroom and would be appropriate school-day doses despite potentially being low during homework time. This is the only study to date systematically examining the effects of long-acting stimulant medication on homework among children with ADHD, and available evidence therefore does not indicate a benefit of long-acting stimulant medication on homework performance.

Combined Treatment

Contrary to hypotheses, combined treatment did not provide additional benefit beyond the main effect of BPT+DRC on the objective measures of homework completion and accuracy. Similar to medication effects, it is possible significant results were not found because 1) the dose of medication was too low to affect home behavior, 2) the effects of BPT+DRC were large and overshadowed potential incremental medication effects (ceiling effect), or 3) there is no additional benefit of stimulants on homework performance beyond effective parenting among children with ADHD. It is unlikely that the doses were too low to result in combined effects, as combining the same dose of stimulant and behavioral treatments employed here results in large, positive effects on completion and accuracy in the classroom (Fabiano et al., 2007).

Additional Limitations

Limitations of psychosocial, psychostimulant, and combined treatments have been discussed above. Additionally, the potential that the STP setting impacted the ability to detect improvements on parent-report measures is a limitation. It is possible that the overall improvement across academic, sports, and peer domains that families report during the course of the STP (O'Connor et al., 2014; Chronis et al., 2004; Fabiano et al., 2007; Pelham et al., 2014) limited the incremental benefit that parents would perceive from the additional parent training program. For instance, the HPC scores herein fall within a 1.5 standard deviation range of normative scores on the HPC (Factor 1 M = 9.82, SD = 6.45; Factor 2 M = 2.97, SD = 2.79; Power et al., 2006) and scores in this study are within a similar range to post-treatment scores from the Multimodal Treatment of ADHD study (Langberg et al., 2010). The beneficial effects on objective measures are impressive given the extensive cross-domain treatment the children were receiving. Although the beneficial effects on homework may have been difficult for parents to detect, the magnitude of improvement was the difference between passing and failing homework assignments, on average. This effect would impact a child's academic grades to the extent that treatment gains transfer to the school year and the child's teachers integrate homework scores into their grading procedures. Additionally, it is important to note that further work is needed to maximize effects on homework performance as the highest average grade (considering accuracy of homework completed) was about 75-80% which is in the C to B- range in typical grading scales.

Homework assignments were determined based upon national guidelines, achievement scores, and the classroom teachers' knowledge about each individual child's abilities. Thus, we are confident that our homework volume and difficulty level closely matched what children were receiving in their regular classrooms. However, whether our belief is accurate remains an empirical question. This trial was conducted in a highly-controlled STP setting, and, though that is a strength of an efficacy trial, future research may need to adapt treatment design to transport less controlled settings. In doing so, it may be beneficial to ensure that the DRC is implemented with fidelity, as it is in the STP, and as has been shown to be important in community settings (Fabiano et al., 2010). The extent to which findings can be generalized may also be impacted by the high proportion of minority families in the current study (83% Hispanic), as this is not representative of the United States population. The treatment itself was not specifically adapted in this study. However, the COPE model (which promotes and reinforces parental empowerment to develop the parenting strategies themselves and work together in small groups) may allow for the cultural diversity to be accommodated without altering the intervention, and the positive results indicate that the non-modified version of the intervention was efficacious in this population. Lastly, parent training attendance varied in the current study, and future studies may find larger effects if attendance were improved.

Conclusions

This study indicates that behavioral treatment in the form of parent skills training and a DRC goal focused on child homework problems results in statistically significant and academically meaningful acute improvements in homework performance among children with ADHD. Children's homework performance was, on average, about two letter grades higher when considering their accuracy of completed work if they received the BPT+DRC intervention compared to the WL group. The most commonly used treatment for children with ADHD, stimulant medication, did not have a significant effect on homework completion and resulted in very limited improvement on homework accuracy, which remained lower than accuracy in the BPT+DRC group. There is currently no evidence to support the recommendation that physicians commonly give to parents guiding them to use long-acting stimulant medication in order to improve their child's homework success and performance (cf. pharmaceutical advertisements for long-acting stimulants claiming such benefits: adpharm.net, 2009). This study suggests that BPT that includes a well-implemented DRC would be a superior treatment recommendation for homework problems among children with ADHD. Finally, this study was an efficacy study conducted in a controlled setting, and replication in regular school settings is the logical next step in this research.

Public Health Significance.

This study provides additional evidence that behavioral treatment is efficacious in improving homework performance among children with ADHD. Despite being advertised as beneficial, long-acting stimulant medication is not recommended for the remediation of homework problems at this time.

Acknowledgments

Author Note: This research was conducted within a grant funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH099030). Dr. Pelham was also supported in part by grants from the Institute of Education Sciences (R324J060024, R324B060045, R324A120136, R324A120169, LO3000065A), the National Institute of Mental Health (MH092466, MH101096, MH083692), and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA11873), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA12414).

Footnotes

Data from weeks 5 and 8 were used because the BPT+DRC individual session occurred during weeks 3 and 4.

As Langberg et al., 2010 recommends, item #18 was omitted from the HPC factors due to low factor loadings.

The only significant comparison indicated that missing baseline HPC data was related to IQ and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms due to one case (p < .05; significance changed to p > .05 with case removed). Analyses on parent-report measures were completed with this individual and without, and results did not change.

The SAS procedure used to run the models on objective measures, PROC GLIMMIX, does not pool F-statistics when using PROC MIANALYZE and does not allow the user to manually pool F-statistics as is possible in PROC MIXED which was used herein for parent-report measures.

Using PROC MIXED, the information necessary to manually pool F-statistics for interaction terms was able to be collected (Wang, Fang, & Jin, 2014). Due to manual pooling, results were compared to an F-table, and specific p-values cannot be provided.

References

- Abikoff H, Gallagher R, Wells KC, Murray DW, Huang L, Lu F, Petkova E. Remediating organizational functioning in children with ADHD: immediate and long-term effects from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(1):113–28. doi: 10.1037/a0029648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anesko KM, Schoiock G, Ramirez R, Levine FM. The Homework Problem Checklist: assessing children's homework problems. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MS, Pelham WE, Licht MH. A comparison of objective classroom measures and teacher ratings of Attention Deficit Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1985;13(1):155–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00918379. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3973249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(2):192–202. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard-Brak L, Brak V. Pharmacotherapy and Academic Achievement Among Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2011;21(6):597–603. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increasing prevalence of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children. United States, 2003 and 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:1439–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis AM, Fabiano GA, Gnagy EM, Onyango AN, Pelham WE, Lopez-Williams A, et al. Seymour KE. An evaluation of the summer treatment program for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using a treatment withdrawal design. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35(3):561–585. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80032-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Forty years of methylphenidate treatment in attention-deficit /hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2002;6(1) doi: 10.1177/070674370200601s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Robinson JC, Patall EA. Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research. 2006;76(1):1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE. A family systems oriented parent training program. In: Barkley RA, editor. Attention deficit hyperactivity: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. pp. 432–461. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Bremner R, Boyle M. Large group community-based parenting programs for families of preschoolers at risk for disruptive behaviour disorders: utilization, cost effectiveness, and outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1995;36(7):1141–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01362.x. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8847377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupaul GJ, Eckert TL, Vilardo B. The effects of school-based interventions for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analysis 1996-2010. School Psychology Review. 2012;41(4):387–412. [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Luckner AE, Whaley GJL, Egeland B. Children's achievement in early elementary school: longitudinal effects of parental involvement, expectations, and quality of assistance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004;96(4):723–730. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein MH, Polloway EA, Foley RM, Patton JR. Homework: A comparison of teachers' and parents' perceptions of the problems experienced by students identified as having behavioral disorders, learning disabilities, or no disabilities. Remedial and Special Education. 1993;14(5):40–50. doi: 10.1177/074193259301400507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Owens JS, Bunford N. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(4):527–51. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.850700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Coles EK, Gnagy EM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Connor BCO, O'Connor BC. A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(2):129–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Pelham WE, Smith BH, Bukstein O, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, et al. Baron-Myak C. Dose-response effects of methylphenidate on ecologically valid measures of academic performance and classroom behavior in adolescents with ADHD. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9(2):163–175. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Burrows-Maclean L, Coles EK, Chacko A, et al. Robb JA. The single and combined effects of multiple intensities of behavior modification and methylphenidate for children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in a classroom setting. 2007;36(2):195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, et al. Burrows-Maclean L. A practical measure of impairment: psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(3):369–85. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Schatz NK, Pelham WE. Summer Treatment Programs for youth with Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric …. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.05.012. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1056499314000443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fabiano GA, Vujnovic RK, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Massetti GM, Pariseau ME, et al. Volker M. Enhancing the effectiveness of special education programming for children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder using a daily report card. School Psychology Review. 2010;39(2):219–239. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(2):159–65. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500471X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, Glutting JJ, Watkins MW. ADHD and achievement: Meta-analysis of the child, adolescent, and adult literatures and a concomitant study with college students. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2007;40(1):49–65. doi: 10.1177/00222194070400010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Dehass AR, Willems PP, Holbein MFD. Examining the relationship between parental involvement and student motivation. Educational Psychology Review. 2005;17(2):99–123. doi: 10.1007/s10648-005-3949-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Wells KC, Kraemer HC, Abikoff HB, Arnold LE, et al. Wigal T. Family processes and treatment outcome in the MTA: negative/ineffective parenting practices in relation to multimodal treatment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28(6):555–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1005183115230. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11104317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeynes WH. A meta-analysis of the relation of parental involvement to urban elementary school student academic achievement. Urban Education. 2005;40(3):237–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(4):567–89. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent KM, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Sibley MH, Waschbusch DA, Yu J, et al. Karch KM. The academic experience of male high school students with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(3):451–62. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9472-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Sibley MH, et al. Kent KM. Young Adult Educational and Vocational Outcomes of Children Diagnosed with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(1):27–41. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9658-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Arnold LE, Flowers AM, Epstein JN, Altaye M, Hinshaw SP, Hechtman L. Parent-reported homework problems in the MTA study: evidence for sustained improvement with behavioral treatment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(2):220–33. doi: 10.1080/15374410903532700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Becker SP. Does long-term medication use improve the academic outcomes of youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;15(3):215–33. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Molina BSG, Arnold LE, Epstein JN, Altaye M, Hinshaw SP, Hechtman L. Patterns and predictors of adolescent academic achievement and performance in a sample of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(4):519–31. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loe IM, Feldman HM. Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(6):643–54. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney J, Milich R. Hyperactivity, inattention, and aggression in clinical practice. Advances in Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1982;3:113–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mautone JA, Marshall SA, Costigan TE, Clarke AT, Power TJ. Multidimensional assessment of homework: an analysis of students with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2012;16(7):600–9. doi: 10.1177/1087054711416795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Jensen PS, et al. Houck PR. The MTA at 8 years: prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(5):484–500. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biological Reviews. 2007;82:591–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Barkley RA. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. In: Mash EM, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 3rd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor BC, Fabiano GA, Waschbusch DA, Belin PJ, Gnagy EM, Pelham WE, et al. Roemmich JN. Effects of a summer treatment program on functional sports outcomes in young children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:1005–1017. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9830-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Burrows-Maclean L, Gnagy EM, Fabiano GA, Coles EK, Tresco KE, et al. Hoffman MT. Transdermal methylphenidate, behavioral, and combined treatment for children with ADHD. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005 doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Burrows-Maclean L, Gnagy EM, Fabiano GA, Coles EK, Wymbs BT, et al. Waschbusch DA. A dose-ranging study of behavioral and pharmacological treatment in social settings for children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9843-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Carlson C, Sams SE, Vallano G, Dixon MJ, Hoza B. Separate and combined effects of methylphenidate and behavior modification on boys with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder in the classroom. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(3):506–15. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.3.506. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8326053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Fabiano GA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 2008;37(1):184–214. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham W, Fabiano G, Massetti G. Evidence-based assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(3):449–476. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Foster EM, Robb JA. The economic impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(6):711–27. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Burrows-MacLean L, Williams A, Fabiano GA, Morrisey SM, et al. Morse GD. Once-a-day Concerta methylphenidate versus three-times-daily methylphenidate in laboratory and natural settings. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E105. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, Milich R. Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms of the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:210–218. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Waschbusch DA, Fabiano GA, Burrows-MacLean L. Summer treatment programs for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Wheeler T, Chronis AM. Empirically supported psychosocial treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27(2):190–205. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_6. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polderman TJC, Boomsma DI, Bartels M, Verhulst FC, Huizink AC. A systematic review of prospective studies on attention problems and academic achievement. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;122(4):271–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Karustis JL, Habboushe DF. Homework success for children with ADHD. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Mautone JA, Soffer SL, Clarke AT, Marshall SA, Sharman J, et al. Jawad AF. A family-school intervention for children with ADHD: results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(4):611–23. doi: 10.1037/a0028188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Werba BE, Watkins MW, Angelucci JG, Eiraldi RB. Patterns of parent-reported homework problems among ADHD-referred and non-referred children. School Psychology Quarterly. 2006 doi: 10.1521/scpq.2006.21.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robb JA, Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Foster ME, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Kuriyan AB. The estimated annual cost of ADHD to the US Education System. School Mental Health. 2011;3(3):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s12310-011-9057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schabenberger O. Introducing the GLIMMIX procedure for generalized linear mixed models. SUGI 30 Proceedings. 2005:196–130. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP. Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (CDISC 4.0) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KK, Frick PJ, Wooton J. Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25(3):317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Waschbusch DA, Garefino AC, et al. Karch KM. Diagnosing ADHD in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(1):139–50. doi: 10.1037/a0026577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson PM, Hamer RM. Cross Crossover Studies Off Your List. SAS Users Group International Annual Conference; 24th, SAS Users Group International. 1999:1303–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Stroup WW. Generalized linear mixed models: modern concepts, methods and applications. CRC press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Issue brief: expectations and reports of homework for public school students in the first, third, and fifth grades. NCES 2009-033. 2008 Retreived from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009033.pdf.

- Visser SN, Disabilities D, Danielson ML, Disabilities D, Bitsko RH, Disabilities D, et al. Blumberg SJ. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider diagnosed and medicated ADHD: United States, 2003-2011. 2014;53(1):34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe RJ, Fabiano GA. Daily behavior report cards: an evidence-based system of assessment and intervention. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Fang Y, Jin M. Combining type-iii analyses from multiple imputations. 2014 Retrieved from http://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings14/1543-2014.pdf.

- Weschler D. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test. 3rd. San Antonio, Texas: Pearson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weschler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. 2nd. San Antonio, Texas: Pearson; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yarandi H. Crossover Designs and Proc Mixed In SAS, 1–11. 2004 Retrieved from http://analytics.ncsu.edu/sesug/2004/SD04-Yarandi.pdf.