Abstract

Objective

Traditional college students are at a critical juncture in the development of prospective memory (PM). Their brains are vulnerable to the effects of alcohol.

Methods

123 third and fourth year college students, 19-23 years old, completed the Self-Rating Effects of Alcohol (SREA), Modified Timeline Follow-back (TFLB), Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Scale (BYAACS) and Alcohol Effects Questionnaire (AEQ) once per month on a secure on-line database, as reported elsewhere (Dager, et al., 2013). Data from the six months immediately prior to memory testing were averaged. In a single testing session participants were administered the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI-DSM-IV-TR), measures of PM (event-based and time-based), and retrospective memory (RM). Based on the average score of six consecutive monthly responses to the SREA, TLFB and AEQ, students were classified as non-drinkers, light drinkers, or heavy drinkers (as defined previously, Dager, et al., 2013). Alcohol-induced amnesia (blackout) was measured with the BYAACS.

Results

We found a relationship between these alcohol use classifications and time-based PM, such that participants who were classified as heavier drinkers were more likely to forget to perform the time-based PM task. We also found that self-reported alcohol-induced amnesia (blackouts) during the month immediately preceding memory testing was associated with lower performance on the event-based PM task. Participants' ability to recall the RM tasks suggested the PM items were successfully encoded even when they were not carried out, and we observed no relationship between alcohol use and RM performance.

Conclusion

Heavy alcohol use in college students may be related to impairments in PM.

Keywords: prospective memory, episodic memory, binge drinking, alcohol, adolescence

Introduction

Prospective memory (PM) is a form of episodic memory, and involves the ability to remember to carry out an intention at some future point in time (Brandimonte, Einstein, & McDaniel, 1996; Kvavilashvili & Ellis, 1996). PM is vital in daily life for functions such as taking medications, turning off the stove, completing assignments, and maintaining appointments, and it is more highly correlated with performance on daily tasks than traditional memory measures (Wilson, 1987). Recent studies have suggested that PM may be affected by heavy alcohol use (e.g., Weinborn, Moyle, Bucks, Stritzke, Leighton, & Woods, 2011). The current study examined PM performance in college students as a function of alcohol use.

PM may require time-cued remembering (e.g., remembering to return a phone call at 3:00 pm) (Levy & Loftus, 1984; Wilkens & Baddeley, 1988), or may be prompted by an event-cue (e.g., remembering to take a roast out of the oven in response to the oven timer) (Einstein & McDaniel, 1990; Harris & Wilkens, 1982; Kvavilashvili, 1992). McDaniel and Einstein's (2000) multiprocess theory posits that the strategic encoding, monitoring, and retrieval demands of a given PM task will likely vary by these characteristics of the target cue. Thus, in most studies, event-based tasks have been found to be easier for individuals to perform, most likely because time-based tasks require the person to perform more self-initiated monitoring and retrieval in order to bring the intention to mind and check a clock or watch (Glisky, 1996; Park, Morrell, Hertzog, Kidder, & Mayhorn, 1997; Sellen, Louie, Harris, & Wilkins, 1997). PM is hypothesized to place more demands on self-initiated monitoring and retrieval processes as compared to retrospective memory (RM) (e.g., McDaniel & Einstein, 2007). In fact, PM is dissociable from RM at the neural (e.g., Simons, Scholvinck, Gilbert, Frith, & Burgess, 2006), cognitive (e.g., Salthouse, Berish, & Siedlecki, 2004), and functional (e.g., Woods, Moran, Carey, Iudicello, Gibson, Atkinson, and the HNRC Group, 2008) levels.

PM is presumed to encompass a variety of cognitive processes (e.g., Smith & Bayen, 2004). This includes the formation of the intention, strategic monitoring during the retention interval, recognition of the external cue, and an effortful and controlled search for retrospective recall, otherwise referred to as self-initiated retrieval. Finally, the actual recall and execution of the intention occurs and the PM task is (or is not) completed successfully. Thus, all measures of PM have a delay between the encoding and retrieval of the prospective task; there must be no explicit prompt when the occasion to act occurs; and there must be a separate ongoing activity (e.g., Einstein & McDaniel, 1990).

Imaging studies have suggested that PM depends on rostral prefrontal cortex (rPFC) functioning, and, in particular, Brodmann area 10 (Benoit et al., 2011). rPFC has been shown to be engaged during the delay period that occurs between the intention formation and the execution of the intention (Burgess, Gonen-Yaacovi, & Volle, 2011). Brain activation during PM tasks has been distinguished from activation in areas associated with vigilance, dual task performance, and working memory (West, 2008). Not surprisingly, damage to prefrontal regions can significantly impair PM functioning (Okuda, Fujii, Yamadori, Kawashima, Tsukiura, & Fukatsu, 1998; Crews, He, & Hodge, 2007; Sowell, Delis, Stiles, & Jernigan, 2001; Burgess, Alderman, Volle, Benoit, & Gilbert, 2009), and PM impairments have been measured in neurological disorders that are presumed to include dysfunction of prefrontal structures (Raskin, Buckheit, & Waxman, 2011; Raskin, Woods, Poquette, McTaggart, Sethna, Williams, & Troster, 2012; Raskin, Maye, Rogers, Correll, Zamroziewicz, & Kurtz, 2014).

In addition, these frontal structures and associated connections continue to develop past adolescence and may be especially vulnerable to the neurotoxic effects of alcohol during this time (Crews and Boettiger 2009; Jacobus and Tapert 2013), which may put college aged students at particular risk (Dager et al., 2013). Adolescents with alcohol use disorder (AUD) demonstrate smaller prefrontal cortex volumes (Medina, McQueeny, Nagel, Hanson, Schweinsburg, & Tapert, 2008; Thomasius, Petersen, Buchert, Andresen, Zapletalova, Wartberg, Nabeling, & Schmoldt, 2003) and binge drinking in adolescence has been associated with increased prefrontal and parietal blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) response but decreased hippocampal BOLD response during verbal learning, perhaps reflecting over-engagement of task-related frontoparietal systems in order to compensate for deficient medial temporal involvement (Schweinsburg, McQueeny, Nagel, Eyler, & Tapert, 2010).

There is evidence that the adolescent hippocampus is also particularly vulnerable to heavy drinking (e.g., Welch, Carson, & Lawrie, 2013), and alcohol effects on the hippocampus could also contribute to retrospective aspects of PM failures. In particular, it has been suggested that alcohol blackouts may be related to alcohol effects on the hippocampus. To our knowledge, the relationship between alcohol-induced amnesia (blackouts) and PM has not been investigated in adolescents or emerging adults, yet blackouts are reported to occur commonly (White, Signer, Kraus, Swartzwelder, 2004). Blackouts do not necessarily follow binge drinking although they are associated with a sudden rise in blood alcohol level (Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, 2002), an effect that has also been shown to disrupt frontal lobe-mediated memory functions (Weissenborn & Duka, 2003) and hippocampal ones (Welch et al., 2013).

In developmental studies, emerging adults (ages 17-20) tend to outperform adolescents (ages 13-16) on PM tasks (Wang, Kliegel, Yang, & Liu, 2006; Ward, Shum, McKinlay, Baker-Tweney, & Wallace, 2005). In particular, tasks high in self-initiated processing and low in environmental support are especially challenging for adolescents (in this study, ages 11-14) (Wang, Liu, Altgassen, Xiong, Akgun, & Kliegel, 2011). This improvement in PM efficiency may be related to the development of controlled behavior in general. Thus, any factors that may influence the maturation of brain functions, such as alcohol consumption, could affect the development of PM in this period of life (Wang et al., 2011).

Alcohol consumption, in fact, is not trivial in this age group. Individuals between the ages of twelve and twenty account for eleven percent of all alcohol consumed in the United States, with 90 percent of alcohol consumption in this age group being characterized as heavy drinking (Centers for Disease Control, 2010). Binge drinking (i.e., five or more drinks for males and four or more drinks for females in a single drinking episode) is especially prevalent in college-aged students, with more than 44 percent of these individuals binge drinking every two weeks and more than 19 percent of these individuals binge drinking more than three times per week (Chen, Dufour, & Yi, 2004).

The relationship between PM performance and alcohol use has been studied most often in adults. Generally, adults with substance use problems report more frequent PM complaints, both in self-report and naturalistic PM daily tasks (Weinborn, Moyle, Bucks, Stritzke, Leighton, & Woods, 2011). In one study heavy alcohol users reported 31.2 percent more problems with long-term PM than non-drinkers and 23.7 percent more problems than individuals who report drinking small amounts of alcohol (Ling, Heffernan, Buchanan, Rodgers, Scholey, & Parrott, 2003). Heavy drinkers with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence have been found to perform more poorly on measures of event-based PM when compared to social drinkers (Griffiths, Hill, Morgan, Rendell, Karimi, Wanagaratne, & Curran, 2012), and time-based PM when compared to matched control participants (Platt, Kamboj, Italiano, Rendell & Curran, 2016). Binge drinkers have been reported to have deficits in time-based PM on the Cambridge Prospective Memory Test (CAMPROMT) (Heffernan & O'Neil, 2012).

In studies of younger subjects, self-report findings have been mixed. One recent study found that short-term binge drinking participants ages 17-19 did not self-report more PM lapses than those who did not binge drink (Heffernan, Clark, Bartholomew, Ling, & Stephens, 2010), but a previous study of binge drinking participants ages 16-19 found that they did (Heffernan, Bartholomew, & Dip, 2006). In a group of emerging adults (mean age 18.7) who were chronic alcohol users and whose alcohol consumption was long-term and heavy, as opposed to the short-term binge drinkers, global impairments in PM were also reported (Heffernan, O'Neill, Ling, Holroyd, Bartholomew, & Betney, 2006).

In studies that have used a standardized clinical measure of PM (Memory for Intentions Screening Test; Raskin, 2009), rather than self-report, substance use was associated with poorer performance in adults (Weinborn, Woods, O'Toole, Kellogg, & Moyle, 2011) and emerging adults (ages 16-18) (Winward, Hanson, Bekman, Tapert, & Brown, 2014). In particular, participants who reported higher levels of alcohol consumption had more difficulties with the time-based tasks and made more omission errors as well as task substitutions (Weinborn et al., 2011). Performance on the time-based items of the MIST also predicted risk-taking behaviors in both adults with substance use disorder and college-aged drinkers (Weinborn, Moyle, Bucks, Stritzke, Leighton, & Woods, 2013).

Although studies have examined how excessive alcohol consumption in college-aged students affects PM performance, more examination of this issue is necessary. Most studies have relied upon self-reports of PM, the accuracy of which is not known. Additionally, there are limited comparisons of PM between different cohorts, including non-drinkers, low to moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers, in studies using college-aged samples.

The primary aim of this study is to determine the effects of drinking behavior on PM functioning in college students. More specifically, the aims are to determine if heavy drinking, including binge drinking, has an effect on either time- or event-based PM and to determine if frequency of blackouts has a relationship with time- or event-based PM.

Methods

a. Participants

Participants were 123 third and fourth year undergraduate college students between the ages of 19 and 23 years (M=20.42 ± 0.92 years). All attended a small liberal arts college, and were originally recruited to participate in a larger NIAAA-funded study BARCS (Brain and Alcohol Research in College Students) (Dager et al., 2013). Initial recruiting was accomplished via school email, flyers, and classroom visits. Exclusion criteria included history of central neurological disorders, head injury accompanied by loss of consciousness of over 1 hour, or concussion within 30 days of participation. Each participant was individually consented with IRB approved consent forms and assigned a randomly generated ID number to protect their identity. Demographic information collected from participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic information by group membership.

| Non Drinker | Light Drinker | Heavy Drinker | χ2 | Cramer's V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 23 | 30 | 13 | 6.65* | 0.480 |

| Male | 17 | 17 | 23 | |||

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic/Latino | 20 | 58 | 32 | 2.71 | 0.198 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 | 9 | 1 | |||

| Race | Caucasian | 28 | 30 | 24 | 4.76 | 0.177 |

| African American | 4 | 10 | 2 | |||

| Asian | 6 | 10 | 4 | |||

| Other | 2 | 2 | 1 |

p<.01

b. Measures

i. Alcohol Use Assessment

BARCS participants received via email a link to a series of secure monthly online questionnaires. Included in these were the Modified Timeline Follow-back (TFLB) (Sobell, Maisto, Sobell, & Cooper, 1979), Self-Rating Effects of Alcohol (SREA) (Schuckit, Tiff, Smith, Wies-Beck, & Kalmtin, 1997), Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Scale (BYAAS) (Kahler, Hustad, Barnett, Strong, & Borsari, 2008) and Alcohol Effects Questionnaire (AEQ) (Rohsenow, 1983). For the current study, data were averaged for each questionnaire completed monthly during the six months immediately preceding memory testing.

The primary variables of interest acquired from these measures were frequency of alcohol consumption, frequency of binge drinking, the number of times the person experienced an alcohol-related blackout (using the scale from the BYAACS as follows: 1 = Never; 2 = 1-2 times; 3 = 3-5 times; 4 = More than 5 times), and the maximum number of drinks consumed in one sitting. Current and past Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV-TR) diagnoses for psychotic, anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders were ascertained using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker, & Dunbar, 1998). Data on frequencies of diagnoses from the MINI are presented in Table 2. Data on use of other substances is presented in Table 3.

Table 2. Frequencies of diagnoses from the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).

| Non-drinker | Light Drinker | Heavy Drinker | χ2 | Cramer's V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Dependence | 0 | 6 | 11 | 9.16** | 0.31 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 0 | 0 | 8 | 13.64** | 0.42 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0.98 | 0.12 |

| Mood Disorder | 3 | 5 | 2 | .686 | 0.10 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| Psychotic Disorder or Anti-Social Personality Disorder | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0.84 | 0.17 |

p<.001

Table 3. Number of days of use of other substances in the past month (1=never; 2=1-2; 3=3-5; 4=6-9; 5=10-14; 6=20 or more).

| Range (days) | N of students reporting use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non Drinker | Light Drinker | Heavy Drinker | ||

| Marijuana | 1-6 | 1 | 8 | 11 |

|

| ||||

| Cocaine, crack | 1-2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| LSD1 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Other hallucinogen | 1-2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Crystal meth | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Heroin | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Opium | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Inhalant | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Ecstasy | 1-2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| PCP2 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| GHB3 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Sleeping medication | 1-2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Sedative/Anxiety medication | 1-3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Stimulant medication | 1-2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Steroid | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Cough medicine | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Pain Medicine | 1-2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Lysergic acid diethylamide

Phencyclidine

Gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid

ii. PM Assessment

PM tasks were embedded within the BARCS testing session. The time-based measure occurred during the self-assessment alcohol use online survey of the BARCS testing session. At the start of the survey, participants were asked to record the current survey question on a colored sheet of paper in their testing packet after fifteen minutes of working on the survey. In order to establish salience for this task, participants were told that the experimenter was tracking the timing of the survey to ensure that it was not excessive in length. The ongoing task was determined to be a sufficiently distracting as it sought detailed information about life stress, mood, as well as alcohol and drug use. Thus, the time-based PM task was to record the current survey question, the time delay was fifteen minutes, and the ongoing task was a self-assessment online survey.

The event-based measure was also administered during the BARCS testing session, in this case during the computer-administered Java Neuropsychological Test (JANET) (http://janet.glahngroup.org). At the start of the computerized task, participants were instructed to hand the “cash voucher” located in their testing packet to the experimenter as soon as they had completed the computerized task. Salience was attached to this task by having the experimenter explain to participants that in order to be compensated for their participation in the study, they needed to turn in the “cash voucher.” The ongoing task, which measured perceptual motor speed, incidental learning, executive function, and impulsivity, was determined to be a sufficiently demanding ongoing task. Thus, the event-based PM task was to hand the “cash voucher” to the experimenter, the time delay was the amount of time that it took the participant to complete the JANET task (typically ten to fifteen minutes) and the ongoing task was the JANET, a computerized test of cognition.

Items were scored as either zero or one. For the time-based task, no implementation of the PM task, incorrect implementation of the task, or correct implementation of the task at the incorrect time was scored as zero and the correct implementation of the PM task was scored as one. For the event-based task, no implementation of the PM task or incorrect implementation of the task was scored as zero and correct implementation of the task in response to the appropriate cue was scored as one. Although neither PM task has been used in previous studies, both are modeled after the types of tasks that are in the Memory for Intentions Test (MIST; Raskin et al., 2010). As this was part of a larger study (BARCS) it was not possible to include a test the length of the MIST. A series of pilot studies were performed to create tasks at a level of difficulty that avoided either ceiling or floor effects, though no formal validation study was undertaken.

iii. Retrospective Recognition Memory Assessment

Participants were also asked to complete a brief retrospective recognition questionnaire. Through two multiple-choice questions, participants were asked to identify the correct PM tasks that they had been instructed to complete. These were included to be sure that participants had understood and encoded the task instructions successfully. Correct responses were scored as one and incorrect responses were scored as zero.

iv. Defining Alcohol Groups

Participants were divided into three alcohol consumption categories based on responses to the TLFB, AEQ and SREA and the AUD diagnosis based on published criteria (Dager et al., 2013). Non-drinkers were those who reported they had never consumed alcohol. Light drinkers (1) did not meet current or past criteria for an AUD and (2) drank <50 % of the weeks during the preceding 6 months as determined from the average of surveys received during the six months immediately preceding the memory testing session. Heavy drinkers either (1) met criteria for a current AUD or (2) drank ≥50 % of the weeks in the preceding 6 months and binge drank for more than half of the number of drinking incidents reported.

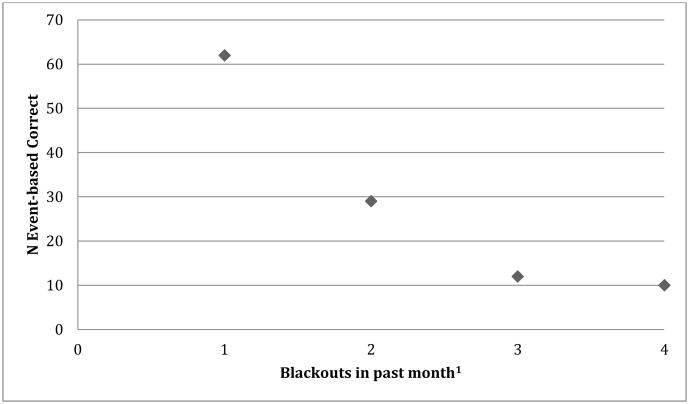

Descriptive findings related to the drinking behavior of each of these groups are presented in Table 4 along with a series of one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with Tukey Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc mean difference scores that demonstrate the differences between the groups on self-report measures of drinking behavior. A scatterplot of the blackout data is presented in Figure 1.

Table 4. Means (standard deviations) and ranges, overall one-way ANOVAs, pair-wise comparisons (Tukey HSD), and effect sizes for drinking behavior of the three groups.

| Non Drinker M (SD) | Light Drinker M (SD) | Heavy Drinker M (SD) | Non Drinker-Light Drinker | Non Drinker-Heavy Drinker | Light Drinker-Heavy Drinker | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On how many days did you have a drink of alcohol in the past 30 days? | 0.00 (0.00) 0-0 | 4.57 (3.91) 0-15 | 5.27 (4.89) 0-20 | 4.50** | 5.27** | 0.77 | 0.23 |

| One how many days did you engage in heavy drinking (4 or more drinks for females and 5 or more drinks for males) in the last 30 days? | 0.00 (0.00) 0-0 | 3.04 (3.00) 0-12 | 5.77 (5.12) 0-20 | 3.04* | 5.77** | 2.73* | 0.27 |

| Number of blackouts experienced in the last 30 days (1=never; 2=1-2 times; 3=3-4 times; 4=5 or more times) | 1.00 (0.00) 1-1 | 1.72 (0.87) 1-4 | 2.25 (1.00) 1-4 | 0.78**b | 1.26** | 0.48* | 0.29 |

| What is the largest number of drinks containing alcohol that you have consumed in a 24-hour period at any time in your life? [1 drink= one 12-oz. beer, one 5-oz. glass of wine, one 12-oz. wine cooler, or 1 oz. of liquor. | 0.00 (0.00) 0-0 | 5.68 (5.02) 0-20 | 8.00 (6.29) 0-20 | 5.56** | 8.00** | 2.43+ | 0.27 |

p<.05;

p<01;

p<.001

Figure 1. Number of individuals with correct responses on the event-based task by blackouts.

1Blackouts 1=never; 2=1-2 times; 3=3-4 times; 4=5 or more

c. Analyses

Chi Square Goodness of Fit Tests were used to compare the groups on the prospective memory and retrospective memory measures. A correlational analysis was used to examine the relationship between number of blackouts in the past month and PM performance.

III. Results

Demographic Differences among Drinking Groups

A Chi Square Goodness of Fit Test revealed significant differences in gender distribution across groups (χ 2 (2) = 6.65; p = 0.036). Post-hoc Bonferroni Confidence Intervals (family α level= 0.05) indicated that significantly fewer females (20%) than males (40%) were categorized as heavy drinkers, (see Table 1). There were no significant differences in ethnic distribution, racial distribution or age across groups.

PM and RM Performance on Time-Based and Event-Based Tasks

Chi Square Goodness of Fit Tests revealed that participants performed significantly better overall on the time-based than event-based tasks of PM (χ 2 (1) = 17.472; p<0.01). Performance on RM tasks did not differ between time-based and event-based cues (χ 2 (1)=0.23; p>0.05).

Influence of Sex on PM and RM Performance

There was no sex performance difference either on the PM time-based task (male mean=0.74, s.d.=0.44) (female mean=0.75, s.d.=0.44) (F(1,121)=.023, p=0.88) or on the PM event-based task (male mean=0.50, s.d.= 0.06) (female mean=0.49, s.d.=0.50) (F(1,121)=.009, p=.92).

Drinking Patterns and PM and RM Performance

A Chi Square Test of Independence was conducted to evaluate the difference among the three drinking groups on their performance on the PM tasks (time-based, event-based). The between-group difference was significant χ 2 (2, N=123) = 12.06, p<01 for the time-based tasks with a moderate effect size (d = 0.65), but not for the event-based tasks χ 2 (2, N=123) = 0.58, n.s. (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Performance of the three groups on the PM tasks.

| Time-Based Task | Non Drinker | Light Drinker | Heavy Drinker | χ2 | Cramer's V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | 36 | 36 | 20 | 12.06* | 0.313 |

| Incorrect | 4 | 11 | 16 | ||

| Percent Correct | 90.0 | 77.0 | 55.6 | ||

| Event-Based Task | |||||

| Correct | 18 | 25 | 18 | 0.58 | 0.069 |

| Incorrect | 22 | 22 | 18 | ||

| Percent Correct | 45.0 | 53.2 | 50.0 |

p<.01

Follow-up pairwise comparisons were conducted for the time-based task to determine which groups differed significantly from each other, using the Bonferroni approach to control for Type I error (overall Family α=0.05). Compared to heavy drinkers a higher proportion of non-drinkers scored correctly on the time-based PM task.

Comparisons of performance on time-based events by drinking behavior reveals non-drinkers had a higher proportion of correct responses than heavy drinkers (see Table 5). Table 6 provides the Chi Square and significance values.

Table 6. Chi-Square and p-values for the comparisons between groups on the time-based PM task.

| Pearson Chi-Square | df | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-drinkers vs Light drinkers | 2.721 | 1 | .099 |

| Light drinkers vs Heavy drinkers | 4.112 | 1 | .043 |

| Non-drinkers vs Heavy drinkers | 11.593 | 1 | .001 |

There were no significant differences between the three groups on either of the RM tasks (time: χ2 (2, N=123) = 5.16, p=0.08; event: χ2 (2, N =123) = 2.10, p=.35) (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Performance of the groups on the RM tasks.

| Time-based Task | Non Drinker | Light Drinker | Heavy Drinker | χ2 | Cramer's |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | 33 | 39 | 23 | 5.16 | 0.205 |

| Incorrect | 7 | 8 | 13 | ||

| Percent Correct | 82.5 | 82.9 | 63.8 | ||

| Event-based Task | |||||

| Correct | 34 | 36 | 27 | 2.10 | 0.131 |

| Incorrect | 5 | 11 | 9 | ||

| Percent Correct | 87.2 | 76.6 | 75 |

Influence of Alcohol Incidents (Blackouts)

Pearson bivariate correlation revealed a significant relationship between number of blackouts in the preceding month and performance on the event-based PM task (r (112) = 0.21 p<05), but not the time-based PM task (r (112) = 0.13; p> 0.05). Figure 1 shows the relationship between numbers of blackouts and score on the event-based task. There was no significant relationship between either of the RM tasks and blackouts (time: r (112) = 0.10; p=.92 and event: r (112) = 0.25; p =.81).

Discussion

This study aimed to compare PM performance among college-aged individuals with different drinking patterns. Although previous research has examined PM and alcohol consumption in this population, most PM measures have been self-report and have not compared different drinking patterns. The PM performance measures implemented in the present study included both a time-based and an event-based task. Overall, participants performed better on the time-based than the event-based PM tasks. Different indicators of drinking behavior had differential effects on PM performance. Heavy drinking was specifically related to the greatest impairment in time-based PM performance. Blackouts were specifically related to event-based PM performance.

An unexpected finding was that participants overall performed better on the time- than the event-based PM tasks. Most previous examinations of performance-based PM have reported better performance on event-based than time-based tasks (Raskin, 2009). In fact, surprisingly, alcohol consumption has been linked to superior performance on an event-based PM task without effects on a time-based PM task (Arana, Blanco, Meilan, Perez, Carro, & Gordillo, 2011). The difficulty of time-based tasks may reflect that participants are expected to self-initiate a response at a specific time in the absence of other cues (Park, Hertzog, Kidder, Morrell, & Mayhorn, 1997). Presumably, the healthy young adult sample in the current study did not have difficulty with time monitoring during the time-based task. It is possible that, given their tight schedules as college students, they are in the habit of monitoring time. More likely, because the two PM measures utilized different ongoing tasks, the attention demands of the ongoing task during the event-based trial may have made it particularly challenging. The ongoing task during the event-based trial was a series of cognitive assessments that, by their nature, require considerable attention. The ongoing time-based task was a self-report survey from which it may have been easier to disengage.

RM scores were consistently high, indicating that the PM measures in this study were properly encoded, and that the appropriate degree of PM “intentionality” was achieved (Burgess, Quayle, & Frith, 2001). The processes underlying this retrospective component of PM are not fully developed in adolescence, but performance falls in older adulthood (Zollig, West, Martin, Altgassen, Lemke, & Kliegel, 2007). Thus, the high level of retrospective performance by the emerging adults in the present study suggests that this age group may be more efficient in the retrospective aspect of PM than the prospective aspect. However, these tasks were quite simple with only a single RM task to be recalled at one time. Thus, tasks with a greater RM load may prove more challenging for this age group.

Drinking behavior was related to time- but not event-based PM. Specifically, drinking was related to impaired time-based PM performance and impairment was greater for heavier drinkers in a dose-dependent manner. This is consistent with previous findings using the CAMPROMT (Heffernan & O'Neil, 2012) and the MIST (Weinborn et al., 2013; Winward et al., 2014). Because the time-based tasks may be more heavily dependent on PFC structures, it may be that they are more sensitive to alcohol effects. These impairments have also been related to inefficient self-initiation, which may result in difficulties with detection of appropriate cues (Griffiths, Hill, Morgan, Rendell, Karimi, Wanagaratne, & Curran, 2012). This suggests that PM may be a useful avenue to explore in attempts to understand the relationship among impulsivity and initiation of alcohol abuse.

In general, our findings are consistent with other studies that have demonstrated that social drinkers tend to be less impaired than heavy drinkers on PM measures. Alcohol users who consume excessively show more errors on long-term, short-term, and internally cued PM on the PM Questionnaire (PMQ), a self-report measure of PM (Heffernan & Bartholomew, 2006) and heavy users have been found to be 30 percent more likely to report compromised PM abilities (Arana et al., 2011; Ling et al., 2003). Beyond this dose-dependent effect, chronic alcoholism appears to be associated with greater cognitive impairment than sporadic heavy alcohol consumption although irregular alcohol consumption can be enough to provoke some degree of cognitive impairment (Sanhueza, Garcia-Morena, & Exposito, 2011).

We also found that alcohol-related blackouts were related to event- but not to time-based PM. Blackouts are associated with a rapid rise in blood alcohol and some researchers have theorized that they are due to impaired memory consolidation (Rose & Grant, 2010). It has long been presumed that PM requires adequate hippocampal activity in addition to that of PFC (Poppenk, Moscovitch, McIntosh, Ozcelik, & Craik, 2010) but that the role of the hippocampus is in remembering the content of the task to be remembered whereas PFC is involved in remembering to remember (e.g., Umeda, Nagumo, & Kato, 2006). Because event-based tasks have more content to be remembered (i.e., both the cue and the intention) it is possible that reduced hippocampal functioning could selectively affect these items.

Numerous studies have uncovered deficits in time- but not event-based PM. To our knowledge no prior study has yielded a dissociation in which varied aspects of alcohol use affect time-based PM and event-based PM differentially. There is some evidence to suggest that time and event-based PM are mediated by separate brain networks. For example, in one study while both event- and time-based PM induced activation in the posterior frontal and parietal cortices, and deactivation in the medial rostral prefrontal cortex, there was activation specific to each condition (Gonneaud, Rauchs, Groussard, Landeau, Mezenge, de La Sayette, Eustache, & Desgranges, 2013). Occipital areas were more activated during event-based PM, while a network comprising the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the cuneus/precuneus and, to a lesser extent, the inferior parietal lobule, superior temporal gyrus, and the cerebellum, was more activated in time-based PM. Zollig, West, Martin, Altgassen, Lemke, & Kliegel (2007) suggested that occipital activation in event-based tasks reflected target checking or cue detection while the regions activated in the time-based tasks reflected time-estimation and monitoring.

Implications

The present study is limited by the nature of the PM measures. It is likely that the ongoing tasks were not of equal difficulty and thus comparisons between the tasks are difficult to interpret. In addition, only simple performance measures were used and these tasks were limited to a single time-based item and a single event-based item, both of which were binary, limiting the range of data collected. Future studies might investigate this question with standardized measures like the MIST, laboratory measures or self-report measures in conjunction with each other.

The present study found that alcohol consumption patterns differentially affected time-based PM performance in a sample of college students. A linear model of alcohol consumption and PM performance in this age group developed by Arana and colleagues (2011) revealed that while the first and second predictors of PM performance were the self-reported quantity of alcohol use, the third predictor was number of years since first alcohol use. Additionally, a link between hippocampal volume and age of first alcohol use has been reported (Casey & Jones, 2010). Certainly, lifetime history of alcohol use needs to be taken into consideration when extrapolating on cognitive repercussions of alcohol consumption.

Future work implementing both performance and self-report measures of PM may be useful to verify that the findings of based on PM performance measures can be extrapolated to daily functioning. Additionally, further examination of the structural and functional underpinnings of PM at this age may help reveal mechanisms of this possible cognitive resilience.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism RO1 AA016599 to Godfrey Pearlson.

We would like to thank Gayna Swart for aiding with statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Sarah Raskin has a financial disclosure as the author of the Memory for Intentions Test.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th, text rev 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SL, Rutstein M, Benzo JM, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH. Sex differences in dopamine receptor overproduction and elimination. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1495–1498. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arana J, Blanco C, Meilan J, Perez E, Carro J, Gordillo F. The impact of poly drug use on several prospective memory measures in a sample of university students. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2011;43:109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit R, Gilbert S, Burgess P. A neural mechanism mediating the impact of episodic prospection on farsighted decisions. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:6771–6779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6559-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ. The social brain in adolescence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:267–277. doi: 10.1038/nrn2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco AM, Valles SL, Pascual M, Guerri C. Involvement of TLR4/type I IL-1 receptor signaling in the induction of inflammatory mediators and cell death induced by ethanol in cultured astrocytes. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175:6893–6899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandimonte M, Einstein GO, McDaniel MA. Eds Prospective memory: theory and applications. USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Tapert SF, Granholm E, Delis DC. Neurocognitive functioning of adolescents: effects of protracted alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Alderman N, Volle E, Benoit RG, Gilbert SJ. Mesulam's frontal lobe mystery re-examined. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2009;27:493–506. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2009-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Gonen-Yaacovi G, Volle E. Functional neuroimaging studies of prospective memory: What have we learnt so far? Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:2246–2257. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Quayle A, Frith CD. Brain regions involved in prospective memory as determined by positron emission tomography. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:545–555. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Grant I the HIV neurobehavioral research center group. Prospective memory in HIV-1 infection. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2006;28:536–548. doi: 10.1080/13803390590949494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter-Hyland EP, Chandler LJ. Adaptive plasticity of NMDA receptors and dendritic spines: implications for enhanced vulnerability of the adolescent brain to alcohol addiction. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2007;86:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM. Neurobiolgoy of the adolescent brain and behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:1189–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Binge Drinking. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/binge-drinking.htm.

- Charness ME. Brain lesions in alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;24:164–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi HY. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18-24 in the United States: results from the 2001-02 NESARC survey. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28:269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney K, Polich J. Binge drinking in young adults: Data, definitions and determinants. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:142–156. doi: 10.1037/a0014414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Braun CJ, Hoplight B, Switzer RC, III, Knapp DJ. Binge ethanol consumption causes differential brain damage in young adolescent rats compared with adult rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1712–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2007;86:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT BoettigerCA. Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2009;93:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dager AD, Anderson BM, Stevens MC, Pulido C, Rosen R, Jiantonio-Kelly RE, Sisante J, Raskin SA, Tennen H, Austad CS, Wood RM, Fallahi CR, Pearlson GD. Influence of alcohol use and family history of alcoholism on neural response to alcohol cues in college drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:E161–E171. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBellis MD. Developmental traumatology: a contributory mechanism for alcohol and substance use disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:155–170. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond I, Jay CA. Alcoholism and alcohol use. In: Goldman L, Bennett JC, editors. Cecil textbook of medicine. 21st. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000. pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dumontheil I, Apperly IA, Blakemore SJ. Online usage of theory of mind continues to develop in late adolescence. Developmental Science. 2010;13:331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein G, McDaniel M. Normal aging and prospective memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 1990;16:717–726. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.16.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fat LN. Are we overestimating the beneficial effects of alcohol in later life? The case of young non-drinkers. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2012;66:A17. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno LM, Conejo NM, Pardo HG, Gomez M, Martin FR, Alonso MJ, Arias JL. Hippocampl agNOR activity after chronic alcohol consumption and alcohol deprivation in rats. Physiology and Behavior. 2001;72:115–221. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, Palus T, Evans AC, Rapoport JL. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisky E. Prospective memory and the frontal lobes. In: Brandimonte M, Einstein G, McDaniel M, editors. Prospective Memory: Theory and Applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gonneaud J, Rauchs G, Groussard M, Landeau B, Mezenge F, de La Sayette V, Eustache F, Desgranges B. How do we process event-based and time-based intentions in the brain? An fMRI study of prospective memory in healthy individuals. Human Brain Mapping. 2014;35:3066–3082. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A, Hill R, Morgan C, Rendell PG, Karimi K, Wanagaratne S, Curran HV. Prospective memory and future event stimulation in individuals with alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2012;107:1809–1816. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilarte TR, McGlothan JL. Hippocampal NMDA receptor mRNA undergoes subunit specific changes during developmental lead exposure. Brain Research. 1998;790:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Wilkens A. Remembering to do things: a theoretical framework and illustrative experiment. Human Learning. 1982;1:123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan TM, Bartholomew J, Dip P. Does excessive alcohol use in teenagers affect their everyday prospective memory? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:138–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan T, O'Neill T. Time based prospective memory deficits associated with binge drinking: Evidence from the Cambridge Prospective Memory Test (CAMPROMPT) Drugs and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;123:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan T, O'Neill T, Ling J, Holroyd S, Bartholomew J, Betney G. Does excessive alcohol use in teenagers affect their everyday prospective memory? Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing. 2006;9:e302–e307. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan TM, Clark R, Bartholomew J, Ling J, Stephens S. Does binge drinking in teenagers affect their everyday prospective memory? Drugs and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;109:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt WA. Are binge drinkers more at risk of developing brain damage? Alcohol. 1993;10:559–561. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A. Serotongeric involvement in learning and memory. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2000;17:79–81. doi: 10.1042/bst0170079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobus J, Tapert SF. Neurotoxic effects of alcohol in adolesence. Annual Reviews of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:703–721. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Overview of key findings, 2002 Monitoring the future- National results on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for social research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C, Hustad J, Barnett N. Validation of the 30-day version of the brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies of Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Lee DY, Lee BC, Jung MH, Kim H, Choi YS, Choi I. Alcohol and cognition in the elderly: A review. Psychiatry Investigation. 2011;9:8–16. doi: 10.4306/pi.2012.9.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, Martin M, McDaniel MA, Einstein GO. Varying the importance of a prospective memory task: differential effects across time- and event-based prospective memory. Memory. 2001;9:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09658210042000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokavec A, Crowe SF. A Comparison of Cognitive Performance in Binge Versus Regular Chronic Alcohol Misusers. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1998;34:601–608. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Weiss F. Neuropharmacology of cocaine and ethanol dependence. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 1992;10:201–233. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1648-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvavilashvili L. Remembering intentions: A critical review of existing experimental paradigms. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1992;6:507–524. [Google Scholar]

- Kvavilashvili L, Ellis J. Let's forget the everyday/laboratory controversy. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1996;19:199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Loftus G. Compliance and memory. In: Harris J, Morris P, editors. Everyday memory, actions, and absent-mindedness. London: Academic Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Differential effect of ethanol on NMDA EPSCs in pyramidal cells in the posterior cingulate cortex of juvenile and adult rats. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2002;87:705–711. doi: 10.1152/jn.00433.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling J, Heffernan TM, Buchanan T, Rodgers J, Scholey AB, Parrott AC. Effects of alcohol on subjective ratings of prospective and everyday memory deficits. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000071741.63467.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber S, Duka T, Marquez HW, Nakovics H, Heinz A, Mann K, Flor H. Effects of repeated withdrawal from alcohol on recovery of cognitive impairment under abstinence and rate of relapse. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2010;45:541–547. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Einstein GO. Strategic and automatic processes in prospective remembering: A multiprocess framework. International Journal of Psychology. 2000;35:296–296. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Einstein GO. Prospective memory: An overview and synthesis of an emerging field. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meacham JA, Singer J. Incentive effects in prospective remembering. Journal of Psychology. 1977;97:191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Medina KL, McQueeny T, Nagel BJ, Hanson KL, Schweinsburg AD, Tapert SF. Prefrontal cortex volumes in adolescents with alcohol use disorders: unique gender effects. Alcoholism: Clinincal and Experimental Research. 2008;32:386–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina KL, Schweinsberg AD, Cohen-Zion M, Nagel BJ, Tapert SF. Effects of alcohol and combined marijuana and alcohol use during adolescence on hippocampal volume and asymmetry. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2007;29:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery C, Ashmore KV, Jansari A. The effects of a modest dose of alcohol on executive functioning and prospective memory. Human Psychopharmacology. 2011;26:208–215. doi: 10.1002/hup.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery C, Fisk JE, Murphy PN, Ryland I, Hilton J. The effects of heavy social drinking on executive function: a systematic review and meta-analytic study of existing literature and new empirical findings. Human Psychopharmacology. 2012;27:187–199. doi: 10.1002/hup.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Kirisci L, Gordon HW, Tarter RE. Alcohol use disorders and neuropsychological functioning in first-year undergraduates. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1994;18:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Office of applied studies. Results from the 1997 national household survey on drug abuse Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 1998. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda J, Fujii T, Yamadori A, Kawashima R, Tsukiura T, Fukatsu R. Participation of the prefrontal cortices in prospective memory: evidence from a PET study in humans. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;253:127–130. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda J, Fujii T, Ohtake HT, Tsukiura T, Yamadori A, Frith DC, Burgess PW. Differential involvement of regions of the rostral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area 10) in time- and event-based prospective memory. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2007;64:233–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscar-Berman M, Shagrin B, Evert DL, Epstein C. Impairments of brain and behavior: the neurological effects of alcohol. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1997;21:65–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppenk J, Moscovitch M, McIntosh A, Ozcelik E, Craik G. Encoding the future: successful processing of intentions engages predictive brain networks. Neuroimage. 2010;49:905–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Hertzog C, Kidder DP, Morrell RW, Mayhorn CB. Effect of age on event-based and time-based prospective memory. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:314–327. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin JS, Leonard G, Perron M, Pike GB, Pitiot A, Richler L, Veillette S, Pausova Z, Paus T. Sex differences in the growth of white matter during adolescence. Neuroimage. 2009;45:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kumaresan V. The mesolimbic dopamine system: the final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse? Neuroscience & Behavioral Reviews. 2006;30:215–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt B, Kamboj S, Italiano T, Rendell R, Curran H. Prospective memory impairments in heavy social drinkers are partially overcome by future event simulation. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:499–506. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4145-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin SA. Memory for Intentions Screening Test: Psychometric properties and clinical evidence. Brain Impairment. 2009;10:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin S, Buckheit C, Waxman A. Effect of Type of Cue, Type of Response, Time Delay and Two Different Ongoing Tasks on Prospective Memory Functioning after Acquired Brain Injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011;22:42–64. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.632908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin S, Maye J, Rogers A, Correll D, Zamroziewicz M, Kurtz M. Prospective memory in schizophrenia: Relationship to medication management skills, neurocognition, and symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia. Neuropsychology. 2014;28:359–65. doi: 10.1037/neu0000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin S, Woods SA, Poquette AJ, McTaggart AB, Sethna J, Williams R, Troster A. A differential deficit in time versus event-based prospective memory in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:201–209. doi: 10.1037/a0020999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Limbic-striatal memory systems and drug addiction. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2002;78:625–636. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ. Drinking habits and expectancies about alcohol's effects for self versus others. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology. 1983;51:752–758. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M, Grant J. Alcohol-induced blackout. Phenomenology, biological basis, and gender differences. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2010;4:61–73. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181e1299d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Butters N. Learning and memory impairments in young and old alcoholics: evidence for the premature-aging hypothesis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1980;4:288–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1980.tb04816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T, Berish D, Siedlecki K. Construct validity and age sensitivity of prospective memory. Memory and Cognition. 2004;32:1133–1148. doi: 10.3758/bf03196887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza C, Garcia-Moreno LM, Exposito J. Weekend alcoholism in youth and neurocognitive aging. Psicothema. 2011;23:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Tiff JE, Smith TL, Wies-Beck GA, Kalmtin J. The relationship between self-rating of the effects (SRE) of alcohol and alcohol challenge results. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:397–404. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsburg AD, McQueeny T, Nagel BJ, Eyler LT, Tapert SF. A preliminary study of functional magnetic resonance imaging response during verbal encoding among adolescent binge drinkers. Alcohol. 2010;44:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellen A, Louie G, Harris J, Wilkins A. What Brings Intentions to Mind? An introductory study of prospective memory. Memory. 1997;5:483–507. doi: 10.1080/741941433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Dunbar G. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Martin ED, Wood PK, Rutledge PC. Alcohol use disorders and neuropsychological functioning in first-year undergraduates. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:304–315. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L. Alcohol and suicide: neurobiological and clinical aspects. Scientific World Journal. 2006;6:700–706. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Scholvinck ML, Gilbert SJ, Frith CD, Burgess PW. Differential components of prospective memory? Evidence from fMRI. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:1388–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Bayen U. A multinomial model of event-based prospective memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 2004;30:756–777. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.4.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Cooper AM. Reliability of alcohol abusers' self-reports of drinking behavior. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1979;17:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Delis D, Stiles JJ, Jernigan TL. Improved memory functioning and frontal lobe maturation between childhood and adolescence: a structural MRI study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2001;7:312–322. doi: 10.1017/s135561770173305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Toga AW, Peterson BS. Cortical abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2003;362:1699–1707. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Alcohol's effect on adolescents. Alcohol Research and Health. 2002;26:287–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng RN, Wojtowicz M, Grade CL. Reliable differences in brain activity between young and old adults: A quantitative meta-analysis across multiple cognitive domains. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34:1178–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Hagino H, Nohara S, Zhou SY, Kawasaki T, Takahashi T, Matsui M, Seto H, Ono T, Kurachi M. Male-specific volume expansion of the human hippocampus during adolescence. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:187–193. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Aarons GA, Sedlar GR, Brown SA. Adolescent substance use and sexual risk-taking behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay SY, Ang BT, Lau XY, Meyyappan A, Collison SL. Chronic impairment of prospective memory after mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2010;27:77–83. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomasius R, Petersen K, Buchert R, Andresen B, Zapletalova P, Wartberg L, Nebeling B, Schmoldt A. Mood, cognition and serotonin transporter availability in current and former ecstasy(MDMA) users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda S, Nagumo Y, Kato M. Dissociative contributions of medial temporal and frontal regions to prospective remembering. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2006;17:267–78. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2006.17.1-2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valles SL, Blanco AM, Pascual M, Guerri C. Chronic ethanol treatment enhances inflammatory mediators and cell death in the brain and in astrocytes. Brain Pathology. 2004;14:365–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Kliegel M, Yang Z, Liu W. Prospective memory performance across adolescence. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2006;167:179–188. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.167.2.179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Liu W, Altgassen M, Xiong WA, Akgun C, Kliegel M. Prospective memory across adolescence: the effects of age and cue focality. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:226–232. doi: 10.1037/a0021306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward H, Shum D, McKinlay L, Baker-Tweney S, Wallace G. Development of prospective memory: tasks based on the prefrontal-lobe model. Child Neuropsychology. 2005;11:527–549. doi: 10.1080/09297040490920186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee J, Kuo M, et al. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Wuethrich B. Dying to drink: confronting binge drinking on college campuses. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weinborn M, Moyle J, Bucks R, Stritzke W, Leighton A, Woods SP. Time-based prospective memory predicts engagement in risk behaviors among substance users: Results from clinical and nonclinical samples. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2013;19:284–294. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinborn M, Woods SP, O'Toole S, Kellogg EJ, Moyle J. Prospective memory in substance abusers at treatment entry: associations with education, neuropsychological functioning, and everyday memory lapses. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2011;26:746–755. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenborn R, Duka T. Acute alcohol effects on cognitive function in social drinkers: Their relationship to drinking habits. Psychopharmacology. 2003;165:306–312. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitlauf C, Woodward JJ. Ethanol selectively attenuates NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission in the prefrontal cortex. Alcohol Clinical and Experimental research. 2008;32:690–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch K, Carson A, Lawrie S. Brain structure in adolescents and young adults with alcohol problems: systematic review of imaging studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2013;48:433–44. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R. The cognitive neuroscience of prospective memory. In: Kliegel M, McDaniel MA, Einstein GO, editors. Prospective memory: cognitive, neuroscience, development, and applied perspectives. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. pp. 261–282. [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Signer ML, Kraus CL, Swartzhelder HS. Experiential aspects of alcohol–induced blackouts among college students. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;12:117–134. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens A, Baddeley A. Remembering to recall in everyday life: An approach to absent mindedness. In: Gruneberg M, Morris P, Sykes R, editors. Practical Aspects of Memory: Current Research and Issues. Vol. 1. London: John Wiley and Sons; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B. The Rehabilitation of Memory. New York: Guilford Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Winward J, Hanson K, Bekman N, Tapert S, Brown S. Adolescent heavy episodic drinking: Neurocognitive functioning during early abstinence. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2014;20:218–229. doi: 10.1017/S1355617713001410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PK, Sher KJ, Bartholow BD. Alcohol use disorders and cognitive abilities in young adulthood: a prospective study. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:897–907. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Moran LM, Carey CL, Dawson MS, Iudicello JE, Gibson S, Grant I, Atkinson JH the HNRC Group. Prospective memory in HIV infection: Is “remembering to remember” a unique predictor of self-reported medication management? Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2008;23:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler DW, Wang CC, Yoast RA, Dickinson BD, McCaffree MA, Robinowitz CB, Sterling ML. The neurocognitive effects of alcohol on adolescents and college students. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollig J, West R, Martin M, Altgassen M, Lemke U, Kliegel M. Neural correlates of prospective memory across the lifespan. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:3299–3314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]