Abstract

Despite demonstrated efficacy, uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) remains low, especially among highest priority populations. This study examined four PrEP messaging factors hypothesized to impact comprehension of PrEP educational information: 1) modality (video versus in-person message delivery); 2) frame (risk versus health focus); 3) specificity (gist versus verbatim efficacy information); and 4) sexual history (administered either before or after PrEP education). We examined message comprehension among 157 young people of color (YPoC) eligible for PrEP, using a series of multiple choice questions. Overall, 65.6% (n= 103) got all message comprehension questions correct. In multivariate analyses, engaging in a sexual history before receiving PrEP education was associated with increased odds of message comprehension (aOR=2.23; 95% CI: 1.06–4.72). This effect was even stronger among those who received PrEP education via video (aOR=3.53; 95% CI: 1.16–10.81) compared to via health educator. This research underscores the importance of sexual history-taking as part of PrEP education and clinical practice for YPoC, and suggests that engaging patients in a sexual history prior to providing them with PrEP education may be key to increasing comprehension.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (U.S.), the HIV epidemic is characterized by disparities. Men who have sex with men (MSM) represent 63% of new infections annually, and account for 82% of all infections among adult and adolescent males;1 30% of new infections are among young MSM (i.e., under the age of 24),2 and of these, 78% are young men of color who have sex with men.1 HIV rates among transgender women (TW) surpass even those reported among MSM,3,4 reaching prevalence in some studies of over 50%.3,5 From 2010 to 2014, HIV incidence increased only among young adults (ages 25–29) and this group had the highest rate of infection (35.8 per 100,000), followed by those ages 20–24 (34.3 per 100,000),6 with a recent modeling study further predicting that 40% of Black/African American MSM will be HIV-seropositive by age 30, and 62% by age 40.7

Annual HIV incidence in the U.S. has remained constant since the 1990s, despite significant investment in prevention interventions.8 Biomedical interventions to reduce maternal-child transmission and structural/needle and syringe exchange interventions to reduce transmission through intravenous drug use have proven extremely effective,9–11 but interventions to reduce sexual transmission have not demonstrated similar success. In 2014, 94% of diagnosed infections in the U.S. were attributable to sexual contact.6 Effective and acceptable interventions to reduce sexual transmission of HIV, especially among young people of color (YPoC), are urgently needed.

At present, one of the most promising HIV prevention strategies is pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which refers to the use of antiretroviral medication by uninfected persons. Daily oral antiretroviral medication for PrEP was FDA approved in 2012; however, uptake remains low,12,13 particularly among MSM of color.14 To date, research on PrEP adoption intentions and outreach efforts have largely focused on adult MSM.14–19 Although this work has identified important factors associated with willingness to take PrEP, little research has examined the best ways to effectively disseminate PrEP information to highest priority populations, such as YPoC.20 Effective messaging requires that audience members fully comprehend its argument in order to make informed decisions and consequently take action.21,22 As such, full-scale implementation of PrEP requires the tailored development and dissemination of PrEP information to YPoC in a way that facilitates an understanding of PrEP efficacy, proper use, and potential side effects.

Computer- and internet-based interventions have garnered a significant amount of attention in recent years, given their potential for overcoming barriers to cost-effective dissemination and implementation.23–25 Multiple PrEP information videos have been developed and are being disseminated on-line, but little work has been undertaken to assess their impact.26 Effective computerized messaging is a strategy with many promising features, including minimal cost for implementation, standardization of message content, individual customization of information through the use of computer algorithms, and the potential for dissemination in diverse settings such as community-based agencies, clinical settings, and the Internet.27 On the other hand, there are concerns that computerized communication lacks interactive feedback, including the use of non-verbal cues that may allow counselors or educators to verify the level of comprehension, the potential to tailor messages to the needs of specific clients, or the ability to answer specific questions that arise for individuals in real-time.28 In order to most effectively reach and engage YPoC in PrEP messages, we need to understand the potential benefits of video-based communication, as well as its potential limitations. However, few studies have directly compared video-based versus in-person messages to assess their differential impact on PrEP message comprehension.

There are several other messaging factors that may impact PrEP message comprehension. First, research on “framing” effects suggests that individuals react differently when prevention choices are framed in terms of potential benefits (i.e., “gain” or health frame: “taking PrEP will help protect you against HIV”) compared to potential harms (i.e., “loss” or risk frame: “if you don’t take PrEP, you increase your risk of becoming infected with HIV).29–31 Second, research on information processing, memory, and reasoning suggests that individuals process health messages based on the level of content specificity, by using either “verbatim” risk information (e.g., PrEP reduces the risk of HIV infection by over 90%) or “gist” risk information (e.g., PrEP is effective; PrEP is good).32 A reliance on gist information has been associated with inaccurate risk perception33, because it minimizes the important nuances, probabilities, and outcomes associated with the risk-related information. However, verbatim information may prove confusing or distracting to patients when they receive health messages, especially those about prevention options.34

In addition to messaging factors, there is evidence that the provision of a brief sexual history assessment – as is recommended as part of the CDC PrEP guidelines – may be an intervention in itself in producing behavior change.35 Specifically, evidence suggests that one assessment method, the Timeline Follow-back (TLFB) Interview, 36 may be particularly effective at raising awareness of the consequences of engaging in risk behaviors, and has been shown to increase both sexual risk reduction motivations and greater risk sensitization, compared to standard assessments.37,38 Furthermore, personal relevance of information may be critical to message “involvement,” which has significant impacts on cognitive processes that govern message comprehension, including attention and elaboration.39 Finally, despite evidence which highlights the importance of sexual history taking in clinical settings,40 research has yet to examine whether engaging in discussion about one’s own risk behavior prior to learning about PrEP impacts comprehension.

In order to examine messaging factors that might optimally impact comprehension among potential PrEP candidates, our research team conducted a large-scale research project that enrolled 500 MSM and transgender women who would be eligible for PrEP prescription based on recent risk behavior (i.e., condomless anal sex in the past 30 days). The present sub-analysis is restricted to the YPoC in the sample (n = 157), defined as those between the ages of 18 and 29 and who reported a race/ethnicity other than white. We assessed overall message comprehension in this sample, and then examined specific messaging factors (and their interactions) that might influence comprehension, controlling for significant psychological and behavioral covariates.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Between February 2012 and April 2014, participants were recruited using passive recruitment methods (i.e., flyers), active recruitment methods (i.e., outreach at bars, events, community-based organizations), and participant referral. Eligible participants: (1) were 18 years of age or older; (2) were born male, regardless of current gender identity; (3) self-reported a negative HIV- status; and (4) reported at least one condomless sex act with a male partner in the 30 days prior to the study visit. It is important to note that eligibility in this sample did not limit condomless sex to casual partners, as mounting evidence suggests that risk for HIV infection among MSM can be linked to both casual and main partners.41–43 As noted above, the present analysis restricted the sample to YPoC as a highest priority population for PrEP. Participants completed a one-time, in-person visit where they received a PrEP educational message, engaged in a sexual history regarding their behavior in the past 30 days, and completed self-report measures on computer. PrEP educational messages included five components: a) What is PrEP? (including the fact that PrEP is a new HIV prevention strategy and a description of the meaning of the words “pre-exposure prophylaxis”); b) How does PrEP work? (including an explanation of the way that anti-HIV medications fight infection and an explanation of why daily adherence is so important to keep concentrations of the medication high); c) How do we know that PrEP works? (including an explanation of iPrEx results); d) Are there any side effects? (including a description of potential side effects and their low prevalence); and e) What about condoms? (including a discussion of the role of condom use in preventing STDs and the importance of the entire toolbox of prevention strategies).

Participants were randomly assigned to one of eight PrEP messaging conditions, based on a 2x2x2 factorial design. Each message was varied by delivery modality (video versus health educator), message frame (risk versus health), and level of specificity (verbatim versus gist). For example, in one message condition, participants received a risk-framed, verbatim message delivered by a health educator; in another condition, participants received a health-framed, gist message delivered via video. All health educators used the same educational script that was used in the video conditions to deliver the PrEP message to the participant. The informational content presented in all messages was the same, however, the language used to present this information differed by condition. As described above, risk-framed messages presented PrEP information in terms of HIV risk and risk-reduction, e.g., “People who are particularly high-risk for HIV infection can take PrEP to reduce their risk of getting HIV.” Health-framed messages presented PrEP in terms of sexual health and health promotion, e.g., “Those who want to increase their control over their sexual health may choose PrEP as part of their strategy to stay HIV-negative.” Verbatim messages presented data from the iPrEx study using detailed numerical information and percentages; gist messages presented the same information without the use of specific numbers or percentages.

Participants in each of the eight conditions were also counterbalanced to complete a sexual history (i.e., interviewer administered TLFB regarding sexual behavior and substance use in the past 30 days) either before or after receiving the PrEP educational message. All participants then completed a self-administered computerized survey on comprehension of the message. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Protections Program at the City University of New York.

Measures

Demographics

Participants self-reported their age, income, education, gender identity, race and ethnicity, and relationship status.

Message Comprehension

To assess message comprehension, participants were given five multiple-choice questions via self-administered survey that were based on the factual information about PrEP presented in the message. Specifically, we asked participants two questions about proper use; 1) “To be effective PrEP must be taken…,” (correct answer: “every day, whether or not I have sex.” ); 2) “Why is it important for PrEP to be taken every day?” (correct answer: “Because you have to make sure there is PrEP medication in your bloodstream at all times, so that it can protect you whenever you are exposed to HIV”). We also asked participants two questions about side effects: 1) “The most common side effect of PrEP is…” (correct answer: nausea/stomach upset).; 2) Which of the following is true about PrEP side effects? (correct answers/check all that apply: If you experience side effects, you should discuss them you’re your health care provider: If you experience side effects, they will likely go away in the first four weeks). Finally, we asked participants about the meaning of partial effectiveness, because PrEP information and guidelines in 2012–2014 stressed the fact that PrEP was not 100% effective in prevention HIV. This question read: “The fact that PrEP is only partially effective in prevention HIV means that…” (correct answer: “Taking PrEP lowers the risk of HIV infection for everyone who takes it, but it doesn’t completely erase their risk.”) We created a dichotomous variable where message comprehension was defined as giving the correct answer to all five questions (Yes/No).

Sexual and Substance Use Behavior

As noted above, a modified version of the semi-structured TLFB was used for the assessment of sexual risk and substance use behavior.36 Using a calendar, interviewers asked participants to report the type of sexual activity (anal or vaginal intercourse; with or without a condom) by partner type (primary or casual) on each of the preceding 30 days. Participants were also asked to report any substance use and heavy episodic alcohol use (i.e., five or more standard drinks on one occasion) on each of the preceding 30 days. Because of skewness in behavioral measures, we created five dichotomous variables indicating whether or not the participant had engaged in each of the following in past 30 days: 1) condomless anal sex with a causal partner; 2) condomless anal sex with an HIV-positive or status-unknown partner; 3) condom use during fewer than 50% of anal sex acts with casual partners; 4) any heavy episodic alcohol use; and 5) any stimulant use (including ecstasy, coke and/or methamphetamine).

Perceived HIV Risk was assessed using a single item in which participants were asked: “How likely do you think you are to get HIV in your lifetime?” Responses were given on a scale ranging from 0 (Not at all likely) to 100 (I will definitely get HIV in my lifetime).44

An abbreviated 6-item Health Numeracy Scale45 was used to assess participants’ ability to understand numerical expressions of risk, such as probabilities and percentiles. The Health Numeracy scale assesses general numeracy (i.e., “Imagine that we rolled a fair, six-sided die 1,000 times. Out of 1,000 roles, how many times do you think the die would come up even?”), as well as comprehension of risk data (i.e., Which of the following numbers represent the biggest risk of getting a disease? 1 in 100; 1 in 1,000; or 1 in 10”). Each of the 6-items was coded as 1=correct versus 0=incorrect, and summed, such that higher scores indicated greater levels health numeracy.

The Subjective Numeracy scale46 (alpha = 0.72) was used to assess participants’ perception of their own ability to perform mathematical tasks and their preferences for the use of numerical versus textual information. The scale consists of 7 items, such as “When people tell you the chance of something happening, do you prefer that they use words (it rarely happens) or numbers (there's a 1% chance)?"). Higher subjective numeracy scores indicate a greater perceived numerical ability and greater preference for receiving numerical information.

The Need for Cognition Scale47 (alpha = 0.80) was used to assess the extent to which participants have a tendency to engage in and enjoy effortful cognitive activities. The scale consists of 18 items, such as “I only think as hard as I have to” and “The notion of thinking abstractly is appealing to me.” Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating stronger need for cognition. Need for cognition has been associated with information processing in decision-making 48 and individuals with low need for cognition have been found to be more susceptible to framing effects.49

Statistical Analyses

All data were analyzed with SPPS version 22. We began by identifying demographic differences in PrEP message comprehension using Chi-square tests. Significant associations between psychological/behavioral covariates and comprehension were examined using t-tests. Chi-square tests were also used to examine significant associations between messaging factors (e.g., modality, sexual history order) and message comprehension. Factors which evidenced significant associations in bivariate analyses were included in multivariate models predicting message comprehension. Finally, because of our primary interest in the development of optimal messaging by modality (e.g., identifying message factors best suited to in-person or video delivery), we fit a separate multivariate regression model predicting comprehension by modality, including both message factors and psychosocial covariates that were significant in bivariate analyses.

RESULTS

The majority of the sample self-identified as male (95.5%; n = 150), with 4.5% (n = 7) identifying as female, transgender, or gender queer. Participant demographics are presented in Table 1, stratified by PrEP message comprehension. The sample ranged in age from 18 to 29 (M = 24.45, SD = 3.11), with half (52.2%) under the age of 25. In response to recent calls for greater specificity in analysis of racial and ethnic identity,50 we first present the number of participants who reported a Hispanic ethnicity (41.4%) and then report participants’ combination of racial and ethnic identities. Almost half of participants (48.7%) identified as non-Hispanic Black. The sample was relatively diverse in regards to educational attainment, but the majority reported relatively low annual income. Close to half the sample (44.6%; n = 70) reported that they were in a significant romantic relationship. Over 68% of participants reported condomless sex with a casual partner in the past 30 days, 31.2% reported condomless sex with a casual partner who was HIV-positive or of unknown HIV-status, and 24.8% of participants reported using condoms for anal sex with casual partners less than half the time. Over 66% of the sample reported heavy episodic alcohol use, and 19.1% reported stimulant use in the past 30 days.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample by PrEP message comprehension (N = 157)

| Total | All Comprehension Questions Correct (n = 103, 65.6%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| N (%) | N (%) | p-value | |

|

|

|||

| Age | -- | ||

| 18–24 | 82 (52.2) | 55 (67.1) | |

| 25–29 | 75 (47.8) | 48 (64.0) | |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 65 (41.4) | 44 (42.7) | -- |

| Race | -- | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 78 (48.7) | 47 (45.6) | |

| Other Non-Hispanic | 10 (6.4) | 8 (7.8) | |

| Hispanic Black | 20 (12.7) | 14 (13.6) | |

| Other Hispanic | 26 (16.6) | 21 (20.4) | |

| Multiracial | 23 (14.6) | 13 (12.6) | |

| Education | .000 | ||

| High School or less | 50 (31.8) | 20 (40.0) | |

| Some/In College | 64 (40.8) | 46 (71.9) | |

| College or more | 43 (27.4) | 37 (86.0) | |

| Income | .000 | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 107 (68.2) | 59 (55.1) | |

| $20,000 or more | 50 (31.8) | 44 (88.0) | |

| Relationship Status | -- | ||

| Single | 87 (55.4) | 61 (70.1) | |

| Partnered | 70 (44.6) | 42 (60.0) | |

| Any CASa with CPb | 107 (68.2) | 70 (65.4) | -- |

| Any CAS with HIV+ or Status-Unknown CP | 49 (31.2) | 27 (26.2) | -- |

| < 50% CUc with CP | 39 (24.8) | 28 (27.2) | -- |

| Heavy Alcohol Use | 104 (66.2) | 70 (67.3) | -- |

| Stimulant Use | 30 (19.1) | 20 (19.4) | -- |

| Frame | -- | ||

| Health Promotion | 76 (48.4) | 52 (68.4) | |

| Risk Reduction | 81 (51.6) | 51 (63.0) | |

| Specificity | -- | ||

| Verbatim | 79 (50.3) | 55 (69.6) | |

| Gist | 78 (49.7) | 48 (61.5) | |

| Modality | -- | ||

| In-person | 80 (51.0) | 56 (70.0) | |

| Video | 77 (49.0) | 47 (61.1) | |

| Sexual History Order | .05 | ||

| Before Message | 75 (47.8) | 55 (73.3) | |

| After Message | 82 (52.2) | 48 (58.5) | |

CAS = condomless anal sex

CP = casual partner

< 50% CU = Less than 50% condom use during anal sex

Bivariate Differences in PrEP Message Comprehension

Overall, 65.6% of participants (n = 103 out of 157) got all five of the message comprehension questions correct. Participants were most likely to answer the question about most common side effects correctly (94.9%), followed by the questions about proper PrEP use (94.3% correct), the reason for daily use (90.4% correct), correct actions to take if they experienced side effects (83.4% correct) and the meaning of partial effectiveness (81.5% correct). As shown in Table 1, PrEP message comprehension was positively associated with both education and income, but not with age, race/ethnicity, or relationship status. There was also a significant association between sexual history order and message comprehension, such that a higher percentage of participants who completed a sexual history before receiving the PrEP message got all comprehension questions correct (73.3%, n = 55 out of 103) compared to those who completed a sexual history after the message (58.5%, n = 48 out of 103).

Table 2 presents the association between psychological variables and PrEP message comprehension. Individuals who got all five comprehension questions correct scored significantly higher than those who did not on health numeracy, subjective numeracy, and need for cognition. There no differences by risk perception between those who got all five comprehension questions correct and those who did not.

Table 2.

Differences in psychosocial variables by comprehension (N = 157)

| All Comprehension Questions Correct

|

||

|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |

|

|

||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Subjective Numeracy | 3.52(0.86) | 4.01(0.90)** |

| Health Numeracy | 2.89 (1.38) | 3.63 (1.46)** |

| Need for Cognition | 3.40 (0.49) | 3.68 (0.52)** |

| Risk Perception | 30.80 (24.82) | 30.67 (23.32) |

p < .05,

p < .01.

Bivariate Differences in Comprehension by Message Factors and Modality

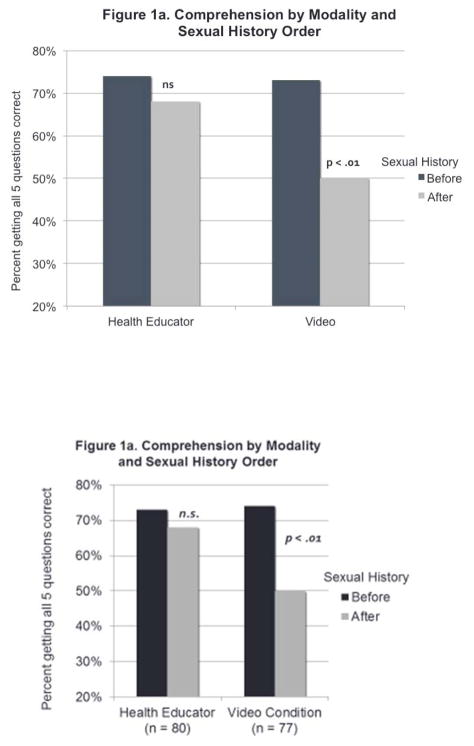

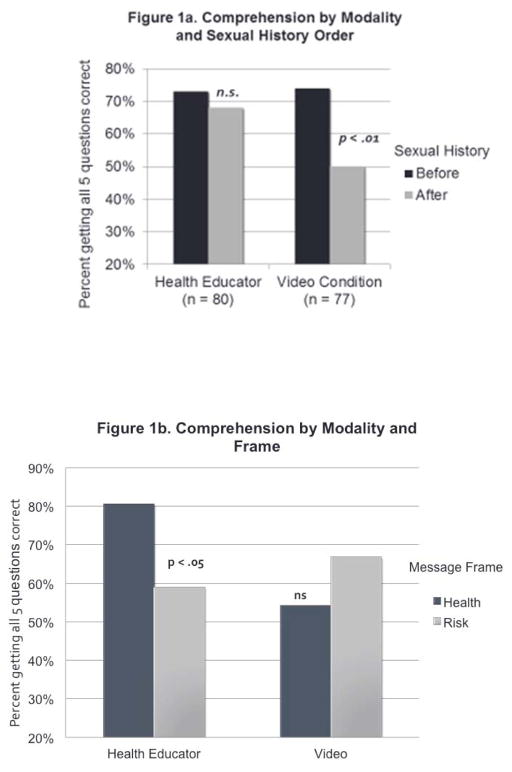

Given our interest in differences in messaging as related to modality (i.e., what message components are most important when the message is delivered via video versus health educator), we examined the effects of each factor (i.e., frame, specificity, and sexual history order) stratified by modality. Among participants who received the message via video, the positive impact on comprehension of engaging in a sexual history prior to receiving the message appeared to be intensified: 73% of participants who had engaged in a sexual history before the message got all comprehension questions correct, compared to only 50% of those who had not engaged in a sexual history before receiving the message, χ2(1)=4.27, p<0.05 (Figure 1a). In contrast, message comprehension among those who received the message from a health educator was significantly impacted by message frame: 80.5% of those who received a health-promotion message got all five questions correct, compared to only 59% of those who received the risk reduction message, χ2(1)=4.41, p<0.05 (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Multivariate Predictors of Comprehension

Table 3 presents multivariate models predicting comprehension for the whole sample of YPoC, as well as by modality (video or educator). Variables included in the multivariate model were those that were significant in bivariate analyses. Due to concerns about multicollinearity because of high intercorrelations among health numeracy, subjective numeracy, and need for cognition, we decided to include only one of these variables. We chose subjective numeracy (participants’ perception of their own ability to perform mathematical tasks and their preferences for the use of numerical versus written information) because this variable can be most easily assessed in a clinical setting; it is not as threatening as asking the computational questions involved in health numeracy, and it avoids the potential for perceived microaggressions that might arise from using the need for cognition scale in clinical practice (e.g., asking a patient whether they tend to “only think as hard as they have to”). For the full sample, step one included education level (with BA or more as the referent group) and subjective numeracy. These two variables resulted in a statistically significant model, but the only parameter that was significant on its own was high school education, such that having only a high school education (compared to having a BA or more) was associated with 86% lower odds of getting all the questions correct. In the second step, we added sexual history order. The step was significant, indicating that – after adjusting for education and subjective numeracy, engaging in a sexual history before receiving the PrEP message was associated with 2.23 times the odds of getting all five comprehension questions correct compared to engaging in a sexual history after receiving the PrEP message.

Table 3.

Predictors of PrEP message comprehension in the total sample and by message delivery modality

| Total Sample (n = 157) | Video Message (n = 77) | Health Educator (n = 80) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | |

|

| ||||||

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Education (ref = BA or more) | ||||||

| High School only | .14*** (.05–0.42) | .13 (.04–.38) | .39 (.10–1.46) | .26 (.06–1.09) | .09** (.03–.34) | .09*** (.02–.33) |

| Some College | .46 (.16–1.30) | .41 (.14–1.16) | .83 (.23–2.93) | .77 (.21–2.85) | .57 (.32–1.02) | .56 (.31–1.01) |

| Subjective Numeracy | 1.38 (.89–2.14) | 1.38 (.88–2.17) | 2.02* (1.11–3.67) | 1.95* (1.03–3.70) | .84 (.42–1.72) | .83 (.41–1.69) |

| Sexual History First | -- | 2.23* (1.06–4.72) | -- | 3.53* (1.16–10.81) | -- | .75 (.23–2.45) |

|

|

||||||

| χ2(3)=26.1*** | χ2(1)=4.6* | χ2(3)=11.5** | χ2(1)=5.4* | χ2(3)=21.4*** | χ2(1)=.64 | |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Among those who received the video message, education was not significant in the first step. Subjective numeracy scores were significantly associated with comprehension, such that every one point increase in subjective numeracy was associated with over a two-fold increase in the odds of getting all five questions correct. Sexual history was also associated with comprehension for those who received the video message. After adjusting for education and subjective numeracy, individuals who engaged in a sexual history before receiving the PrEP message via video had over 3.5 times the odds of getting all five comprehension questions correct compared to those who engaged in a sexual history after receiving the PrEP message.

It is important to note that none of the results presented in this analysis of YPoC were replicated in the full sample or with other cohorts (i.e., young white people (n = 76); older men of color who have sex with men (n = 151); or older white MSM (n = 107)). As such, these analyses suggest findings that appear to be unique to the high priority cohort of YPoC.

DISCUSSION

We conducted an analysis of individual and messaging-related factors and procedures likely to influence comprehension among a sample of high-risk young people of color (YPoC), including both young MSM and young transgender women. Our findings point to: 1) the critical importance of sexual history taking as part of PrEP education and clinical practice, and 2) the potential impact of engaging patients in a sexual history prior to providing them with PrEP education as a key to increasing comprehension. In this sample, engaging in a sexual history prior to receiving education about PrEP was associated with between 2.2 (whole sample) and 3.5 (video messaging group) times the odds of fully comprehending the information. It is important to note that this effect on comprehension existed over and above traditional barriers to comprehension, including education level and subjective numeracy. Messages targeting individuals with less education often oversimplify or strip-down informational content in an effort to increase comprehension. These data suggest that increasing the personal relevance of the information can increase comprehension while maintaining the same level of complexity in content.

Although the mechanism through which engagement in providing a sexual history increased comprehension was not directly tested in this study, we hypothesize that it is related to the increased self-relevance of HIV prevention information. Research on the self-reference effect has demonstrated significant positive impact on memory when information is considered self-relevant,51 which is mediated by differences in brain processing.52 Neuroimaging data demonstrate that self-related processing during health communication is positively associated with later behavior change.53 Given their highly vulnerable position vis-à-vis HIV transmission and the HIV treatment cascade,54–56 YPoC are bombarded with messages about the inevitability of HIV infection, causing them to become inured to or even dissociated from prevention messages. Furthermore, recent focus groups with young African-American MSM indicate that some barriers to adoption of HIV prevention can be partially explained by a feeling of powerlessness and apathy in the community, largely associated with racism and homophobia.57 In a health care context, brief interactions that deem the patient unimportant and/or feeling a lack of self-relevance in the interaction have been shown to lead to disengagement from health care utilization, especially for individuals of color.58,59 Our data suggest that engaging in a sexual history may heighten the self-relevance of HIV prevention information, increasing memory and cognitive processing during PrEP education.

Increasing self-relevance may be even more important in the context of video-delivered messaging, as our data indicate even stronger impacts for participants who received the video message. This finding is particularly relevant to emerging PrEP education practices that move from face-to-face interactions to online platforms. In our study, the sexual history was done in person, by a trained health educator, even for participants in the video condition. For online PrEP messaging delivery, it might be useful to test computerized sexual history tools, some of which have already been created.60,61 Alternatively, hybrid PrEP counseling protocols may be adopted, where the initial contact is made in person by a trained counselor (during which sexual history is discussed), followed by a video viewing of PrEP information.

Finally, our data suggest that message comprehension was higher when YPoC received a “health-framed” message from the health educator, compared to the “risk-framed” message. Building on past evidence that gain-frames improve comprehension during in-person communication, this finding may be even more relevant for YPoC, who are multiply stigmatized and may have had negative experiences with the health care system. For YPoC, perceiving that a PrEP counselor is focused on their health – rather than simply their risk for HIV – may make them more receptive to education and intervention. More data are needed to understand these factors, and their impact on PrEP adoption among YPoC.

This research is subject to several limitations. Our study was conducted in New York City and our sample was comprised of a small sample of young men and transgender women who have sex with men and do not identify as white, and, as such, may not be generalizable to other samples. In fact, as noted above, our findings on the importance of sexual history for comprehension were not replicated with other cohorts in the larger study. We did not directly measure message self-relevance, and are therefore unable to test our hypotheses about the mechanism by which engagement in sexual history may impact comprehension or future PrEP adoption., We did not assess knowledge about PrEP prior to participants’ receiving the message; while, randomization should have accounted for any pre-existing differences in knowledge, we were unable to examine the impact of the PrEP messages on risk perception directly. Given the limited number of young transgender women and those who identified as gender queer in our sample, we were unable to examine differences by gender identity. Future research is needed to better understand the impact of PrEP messaging on comprehension among young transgender women and gender queer youth of color.

Despite these limitations, this study of YPoC – a high-priority population for PrEP education and engagement – has significant implications for the integration of PrEP programs into clinical practice. Consistent with CDC guidelines, our data suggest that sexual history conversations should be a vital part of any PrEP education and counseling sessions.62 Unfortunately, evidence indicates that engaging patients in sexual history is not normative. Taking sexual histories is not a routine practice among health care providers, and it is especially likely to be deferred during urgent care that may include HIV and STI testing or treatment.62–65 Lingering discomfort with and/or stigmatization of same-sex behaviors may lead to their failure to be routinely discussed by and with providers,66 which represent missed opportunities for appropriate prevention and PrEP counseling. PrEP provides a unique opportunity to revitalize calls for sexual history taking in routine practice, and may underscore the importance of such engagement with patients. These data emphasize the urgent need to involve YPoC in HIV prevention conversations, which they perceive to be self-relevant and that are focused on their health, rather than their risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was funded by R01MH095565 (S.A. Golub, PI) and Kristi Gamarel was supported by training grant T32MH 078788 (L. Brown, PI) from the National Institutes of Mental Health.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the hard work of members of the Hunter HIV/AIDS Research Team (HART), including Anthony Surace, Kailip Boonrai, Inna Saboshchuk, and Louisa Thompson. We also thank Dr. Jeffrey Parsons and the staff at the Center for HIV Educational Studies and Training. We are grateful to the participants who gave their time and energy to this study, and to Dr. Willo Pequegnat and Dr. Michael Stirratt for their support.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: As part of an NIH-funded PrEP Demonstration Project (R01AA022067), Sarit Golub receives study drug and partial support for DBS testing from Gilead Sciences. Kristi Gamarel and Corina Lelutiu-Weinberger declare that they have no conflict of interest

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed April 30, 2015];HIV Surveillance - Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/slideSets/index.html.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 23, 2014];HIV among gay and bisexual men. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/msm_fact_sheet_final_2014.pdf.

- 3.Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet infectious diseases. 2012;13(3):214–222. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kellogg TA, Clements-Nolle K, Dilley J, Katz MH, McFarland W. Incidence of human immunodeficiency virus among male-to-female transgendered persons in San Francisco. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;28(4):380–384. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed December 2, 2015];HIV Surveillance Report, 2014. 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-us.pdf.

- 7.Matthews DD, Herrick AL, Coulter RWS, et al. Running backwards: Consequences of current HIV incidence rates for the next generation of Black MSM in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):7–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1158-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with men-21 cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(37):1201–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suksomboon N, Poolsup N, Ket-aim S. Systematic review of the efficacy of antiretroviral therapies for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 2007;32(3):293–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mofenson LM, McIntyre JA. Advances and research directions in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission. The Lancet. 2000;355(9222):2237–2244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02415-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Des Jarlais DC, Marmor M, Paone D, et al. HIV incidence among injecting drug users in New York City syringe-exchange programmes. The Lancet. 1996;348(9033):987–991. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer KH, Krakower DS. If PrEP decreases HIV transmission, what is impeding its uptake? Clinical Infectious Disease. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection Current status, future opportunities and challenges. Current Opinions. 2015;75(3):243–251. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0355-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister J, Smith H, Conway-Washington C. Minimal awareness and stalled uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among at risk, HIV-negative, Black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2015;29(8):423–429. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, Surace A, Lelutiu-Weinberger C. From efficacy to effectiveness: Facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2013;27(4):248–254. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayala G, Makofane K, Santos G-M, et al. Access to basic HIV-related services and PrEP acceptability among men who have sex with men worldwide: Barriers, facilitators, and implications for combination prevention. Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/953123. Article ID 954123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoff CC, Chakravarty D, Bircher AE, et al. Attitudes toward PrEP and anticipated condom use among concordant HIV-negative and HIV-discordant male couples. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2015;29(7):408–417. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Surace A. Demographic Differences in PrEP-Related Stereotypes: Implications for Implementation. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mayer KH, Oldenburg CE, Novak DS, Elsesser SA, Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ. Early adopters: Correlates of HIV chemoprophylaxis use in recent online samples of US men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crosby RA, Geter A, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF. Acceptability of condoms, circumcision, and PrEP among young black men who have sex with men: A descriptive study based on effectiveness and cost. Vaccines. 2014;2(1):129–137. doi: 10.3390/vaccines2010129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGuire WJ. The communication/persuasion matrix. In: Lipstein B, McGuire WJ, editors. Evaluating advertising. New York: Advertising Research Foundation; 1978. pp. xxvii–xxxv. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGuire WJ. Theoretical foundations of campaigns. In: Rice RE, Atkin CK, editors. Public communication campaigns. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1989. p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Bauermeister J, Zhang C, LeGrand S. Youth, technology, and HIV: Recent advances and future directions. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2015;12(4):500–515. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0280-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ybarra ML, Bull SS. Current trends in internet- and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2007;4(4):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swendeman D, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Innovation in sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevention: Internet and mobile phone delivery vehicles for global diffusion. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(2):139–144. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336656a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simoni JM, Kutner BA, Horvath KJ. Opportunities and challenges of digital technology for HIV treatment and prevention. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2015;12(4):437–440. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0289-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: A meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(1):107–115. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan PS, Grey JA, Simon Rosser BR. Emerging technologies for HIV prevention for MSM: What we'velearned, and ways forward. J Acquir Immune Dific Syndr. 2013;63(1):S102–S107. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182949e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: the role of message framing. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(1):3. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salovey P, Schneider TR, Apanovitch AM. Message framing in the prevention and early detection of illness. The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice. 2002:391–406. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;43(1):101–116. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reyna VF, Adam MB. Fuzzy-Trace Theory, Risk Communication, and Product Labeling in Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Risk analysis. 2003;23(2):325–342. doi: 10.1111/1539-6924.00332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reyna VF. A tehory of medical decision making and health: Fuzzy trace theory. Med Decis Making. 2008;2008(28):850–865. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08327066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reyna VF. Risk perception and communication in vaccination decisions: a fuzzy-trace theory approach. Vaccine. 2012;30(25):3790–3797. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke LE, Wang J, Sevick MA. Self-monitoring in weight loss: A systematic review of the literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline FollowBack user’s guide: A calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinhardt LS. Effects of a detailed sexual behavior interview on perceived risk of hiv infection: Preliminary experimental analysis in a high risk sample. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;25:195–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1014888905882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinhardt LS, Carey KB, Carey MP. HIV risk sensitization following a detailed sexual behavior interview: a preliminary investigation. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;23:293–398. doi: 10.1023/a:1005505018784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Celsi RL, Olson JC. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. Journal of Consumer Research. 1988:210–224. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanier Y, Castellanos T, Barrow RY, Jordan WC, Caine V, Sutton MY. Brief sexual histories and routine HIV/STD testing by medical providers. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2014;28(3) doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell JW, Harvey SM, Champeau D, Seal DW. Relationship factors associated with HIV risk among a sample of gay male couples. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):404–411. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9976-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoff CC, Beougher SC, Chakravarty D, Darbes LA, Neilands TB. Relationship characteristics and motivations behind agreements among gay male couples: Differences by agreement type and couple serostatus. AIDS Care. 2010;22(7):827–835. doi: 10.1080/09540120903443384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomez AM, Beougher SC, Chakravarty D, et al. Relationship dynamics as predictors of broken sexual agreements about outside sexual partners: implications for HIV prevention among gay couples. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1584–1585. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gamarel KE, Golub SA. Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in romantic relationships. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;49(2):177–186. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9646-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lipkus IM, Samsa G, Rimer BK. General performance on a numeracy scale among highly educated samples. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:37–44. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faberlin A, Zikmund-Fusher BJ, Ubel PA, Jankovic A, Derry HA, Smith DM. Measuring numeracy without a math test: Development of the subjective numeracy scale. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:672–680. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07304449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, Kao CF. The efficient assessment of need for cognition. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1984;48(3):306–307. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levin IP, Huneke ME, Jasper JD. Information processing at successive stages of decision making: Need for cognition and inclusion-exclusion effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2000:171–193. doi: 10.1006/obhd.2000.2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith SM, Levin IP. Need for cognition and choice framing effects. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 1996:283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider J, Bouris A, Smith D. Race and the public health impact potential of PrEP in the United States. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Symons CS, Johnson BT. The self-reference effect in memory: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(3):371. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moran JM, Macrae CN, Heatherton TF, Wyland C, Kelley WM. Neuroanatomical evidence for distinct cognitive and affective components of self. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18(9):1586–1594. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.9.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chua HF, Ho SS, Jasinska AJ, et al. Self-related neural response to tailored smoking-cessation messages predicts quitting. Nature Neuroscience. 14(4):426–427. doi: 10.1038/nn.2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, et al. HIV among black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: a review of the literature. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(1):10–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Millett GA. Disparities in HIV treatment, engagement, adherence, and outcomes. Paper presented at: International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence; June 2–4, 2013; Miami, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oster AM, Wiegand RE, Sionean C, et al. Understanding disparities in HIV infection between black and white MSM in the United States. AIDS. 2011;25(8):1103. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283471efa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voisin DR, Bird JD, Shiu C-S, Krieger C. “It's crazy being a Black, gay youth.” Getting information about HIV prevention: A pilot study. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;36(1):111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Halterman JS. Ambulatory care among young adults in the United States. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151(6):379–385. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cherry DK, Woodwell DA, Rechtsteiner E. National ambulatory medical care survey: 2005 summary. Adv Data. 2007;387(387):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mustanski BS. Are sexual partners met online associated with HIV/STI risk behaviours? Retrospective and daily diary data in conflict. AIDS Care. 2007;19(6):822–827. doi: 10.1080/09540120701237244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pedersen ER, Grow J, Duncan S, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Concurrent validity of an online version of the Timeline Followback assessment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):672. doi: 10.1037/a0027945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed December 4, 2015];Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States - 2014 Clinical practice guidelines. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014.pdf.

- 63.Metsch LR, Pereyra M, del Rio C, et al. Delivery of HIV prevention counseling by physicians at HIV medical care settings in 4 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1186–1192. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laws MB, Bradshaw YS, Safren SA, et al. Discussion of sexual risk behavior in HIV care is infrequent and appears ineffectual: a mixed methods study. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(4):812–822. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9844-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wimberly YH, Hogben M, Moore-Ruffin J, Moore SE, Fry-Johnson Y. Sexual history-taking among primary care physicians. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98(12):1924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernstein KT, Liu K-L, Begier EM, Koblin B, Karpati A, Murrill C. Same-sex attraction disclosure to health care providers among New York City men who have sex with men: implications for HIV testing approaches. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(13):1458–1464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]