Abstract

Mutation in IDH1 gene was suggested to be associated with bad prognosis in cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML). However, there are conflicting data about its prognostic impact. Besides, its prevalence and prognostic significance in Egyptian patients still not fully stated. We aimed to assess the prevalence of IDH1R132 mutation in Egyptian CN-AML patients, its correlation with FAB subtypes, and clinical outcome of those patients. Sequencing of amplified IDH1 gene exon four from 50 patients was performed to detect codon R132 point mutation. High prevalence of IDH1 mutation was detected in our patients (9/50, 18 %). Mutated IDH1R132 was associated with older age and higher platelets count (p = 0.04 and 0.01 respectively). The most common FAB subtype associated with mutated IDH1R132 was AML-M2 followed by M4. In multivariate analysis, IDH1R132 mutation was found as independent prognostic variable. It was significantly associated with lower CR and shorter OS (p = 0.06 and 0.009 respectively).

Keywords: IDH, Normal karyotype AML, Mutations in AML

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous disease in adult with bad prognosis and short overall survival (OS). In spite of advanced chemotherapy protocols, more intensive research provides critical insights on the pathogenesis of AML [1]. Cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML) represents 40–50 % of all AML cases with separate entities in WHO classification [2]. Identification of new gene mutations provides useful markers for diagnosis, prognosis assessment, and making therapeutic decision with monitoring therapy [3]. The most frequent of these aberrations are mutations in the nucleophosmin (NPM1) gene, which are present in approximately 50 % of these patients [4]. Other common genetic lesions are internal tandem duplications (ITDs) in the Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) gene that occur in nearly 20–30 % of CN-AML cases [5]. Furthermore, loss-of-function mutations in both Wilms-tumor (WT1) and the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (CEBPA) genes are present in about 10 % of CN-AML cases [6, 7].

These mutations do not only play a role in the pathogenesis of CN-AML but also have profound established prognostic impact. Genetic analysis for these aberrations can serve as a basis for risk stratification and molecularly based therapies. However, a large proportion of CN-AML patients still lack reliable prognostic markers, which underlines the need for further molecular characterization of these patients. Currently, no known mutations are identified in about 20–30 % of CN-AML cases, suggesting the possibility that more mutations likely exist [8].

A novel mutation was detected in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1); a metabolic gene frequently mutated in glioma and first discovered with favorable prognosis [9, 10]. IDH1 is a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) dependent enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative carboxylation of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate. It has a key role in production of cystolic reduced form of NADPH necessary for the generation of reduced glutathione, a main antioxidant in mammalian cells [11]. Many studies reported that this mutation occurs at conserved arginine residue at codon 132 (R132) within the substrate binding site of the enzyme and was strongly associated with normal cytogenetic status in AML patients [12, 13]. A few years ago, Marids and colleagues sequenced the entire genome of a CN-AML and detected IDH1 mutation that cause substitution of R132 (16/188 samples: R132C in 8 samples, R132H in 7 samples, and R132S in 1 sample) [8]. Many researches focused on the frequency and correlation of mutational status with the clinical outcome. Limited information is available on the morphological patterns associated with IDH1R132 mutations in AML. A single study involving Chinese population reported clinical and biological features of AML with IDH1R132 mutation [13]. There is no enough reports for Egyptian CN-AML cases with this mutation.

Our study was conducted to assess the prevalence of IDH1R132 mutation in Egyptian CN-AML patients and its correlation with laboratory, and clinical data and to evaluate its impact on the therapeutic outcome of those patients.

Patients and Methods

We prospectively screened pretreatment peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) samples (the sample choice was based only on the blast presence in the sample) from 113 de novo AML patients from January 2011 to August 2014. Among those, 50 patients were found to have CN-AML (aged from 17 to 78 years, 27 males and 23 females). To establish CN-AML, pretreatment samples from all patients were studied by G banding analysis, more than 20 metaphase cells from diagnostic BM had to be analyzed and reported as normal karyotype according to the international system for human cytogenetic nomenclatures (ISCN) [14]. Patients’ laboratory data were collected including complete blood counts (CBC), PB/BM smear morphology, flow cytometric immunophenotyping, and cytogenetic results. Patients were treated according to the standard AML regimen including daunorubicin, and cytrabine as induction therapy, followed by high-dose cytrabine as consolidation therapy. Although BM transplantation was an integral part of the treatment plan, only seven patients underwent allogeneic BM transplantation. The few number of patients who undertook BM transplantation was partly due to the low number of patients who achieve CR, less availability of matched donor and the fewer patients who were willing to perform this procedure. Informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the medical ethics committee. Demographic, clinical and laboratory findings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data in patients’ groups according to IDHR132 mutation

| Parameter | All patients | Mutated IDH1 | Wild IDH1 | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 50 | 9 (18 %) | 41 (82 %) | – |

| Age, years (median, range) | 44 (17–78) | 58 (33–78) | 45 (17–71) | 0.042 |

| Sex (M/F) | 27/23 | 5/4 | 22/19 | 0.9 |

| PS (ECOG) (n, %) | ||||

| 1 | 23 (46 %) | 7 (77.8 %) | 16 (39.0 %) | |

| 2 | 19 (38 %) | 2 (22.2 %) | 17 (41.5 %) | N/A |

| 3 | 8 (16 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 8 (19.5 %) | |

| Splenomegaly (n, %) | 23 (46 %) | 2 (22 %) | 21 (51 %) | 0.11 |

| Hepatomegaly (n, %) | 8 (16 %) | 3 (33 %) | 5 (12 %) | 0.81 |

| Lymphadenopathy (n, %) | 5 (10 %) | 3 (33 %) | 2 (5 %) | 0.85 |

| Hb, gm/dl (median and range) | 8.6 (4.5–12.6) | 9.1 (4–12) | 8.4 (4.1–12.6) | 0.71 |

| WBCs, ×103/µl (median and range) | 28.6 (3.2–132) | 33 (3.2–101) | 52.5 (13–132) | 0.13 |

| Platelets, ×103/µl (median and range) | 72 (5–139) | 74 (39–139) | 41.5 (5–121) | 0.01 |

| BM blasts, % (median and range) | 53 (22–96) | 46.5 (27–85) | 58 (22–96) | 0.37 |

| FAB classification | ||||

| M1 | 4 (8 %) | 1 (11.1 %) | 3 (7.3 %) | NA |

| M2 | 14 (28 %) | 5 (55.6 %) | 9 (22.0 %) | |

| M4 | 17 (34 %) | 3 (33.3 %) | 14 (34.1 %) | |

| M5 | 12 (24 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 12 (29.3 %) | |

| M6 | 3 (6 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 3 (7.3 %) | |

IDH1 Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1, PS performance status, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Hb Hemoglobin, WBCs white blood cell counts, BM bone marrow, FAB French–American–British classification

*Significant p values are shown in bold

Sequencing Analysis for IDH1 Gene

Genomic DNA was extracted from PB/BM samples using GeneJET Genomic DNA purification kit (Fermentas, EU). The genomic region of the IDH1 gene (exon four) containing the mutational hotspot codon R132 was amplified according to Sanson et al. [15] using the following primers: IDH1-forward 5′-TGCCACCAACGACCAAGTCA-3′ and IDH1-reverse 5′-TGTGTTGAGATGGACGCCTATTTG-3′ (AccuOligo, Bioneer, Korea). PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 25 μl containing 12.5 µl of Maxima hotstart PCR master mix 2× (Thermo Scientific) (containing Maxima hot Taq DNA polymerase, hot start PCR buffer, 400 µM of each dNTP, and 4 mM Mg+2), 0.1 µl of each primer (100 picomol), and 1 µl of extracted DNA (20–50 ng) and completed to 25 µl with molecular grade water. The PCR was carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the following steps: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 4 min, 35 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer. Cycle sequencing of purified PCR products were done using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit. The reaction mix (10 µl) contains 2 µl of Big dye terminator ready reaction mix (Applied Biosystem, USA), 2 µl of 2× diluting buffer (Applied Biosystem, USA), 5.7 µl PCR products and 0.3 µl of IDH1-forward primer (10 picomol) (AccuOligo, Bioneer, Korea). Cycle sequencing was done on GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by performing 25 cycles of: 96 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 4 min. Purification of the extension products was done using Centri-Sep Cycle Sequencing Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer instructions. Then the pellet was re-suspended in 10 µl HiDiformamide and samples were sequenced on a 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed using the Sequencing Analysis v5.4 software (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

For descriptive statistics of qualitative variables, the frequency distribution procedure was run with calculation of the number of cases and percentages. For descriptive statistics of quantitative variables the median and range were used to describe central tendency and dispersion. For analysis of the differences in proportions, Chi square test was used, Fishers exact test was used if the assumptions of Chi square were violated. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the level of quantitative variables that violated the normality assumptions. Survival analysis was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier Product-Limit Estimator. Comparison of the survival was performed by the Log-Rank Test; continuous variables were dichotomized at the median cut-off. The hazard ratio in univariate and multivariate analyses was calculated by the cox regression analysis. Data were analyzed on a personal computer running Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS©) for windows, release 15. All tests are considered significant if p ≤ 0.05, all statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Frequency of IDH1R132 Mutation

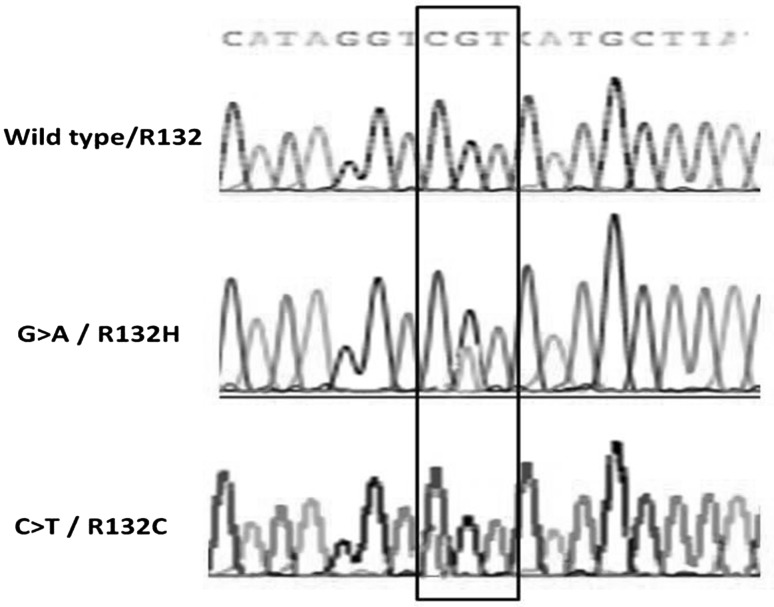

To determine the frequencies of IDH1 R132 mutations, we screened DNA of 50 newly diagnosed patients with CN-AML by PCR of IDH1 exon 4 followed by direct sequencing. Wild IDH1 R132 was detected in 41/50 patients (82 %) in which R132 is normally encoded by CGT codon (wild IDH1 group) while the remaining 9/50 patients (18 %) carried mutated IDH1 R132 (mutatedIDH1 group). Within the 9 mutated cases, CGT > CAT mutation was detected in 6/9 patients (66 %) leading to an R132H substitution and CGT > TGT mutation leading to R132C substitution was detected in 3/9 patients (33.3 %) (Fig. 1). There were no other mutations detected in our patients. All mutations were heterozygous missense point mutation.

Fig. 1.

Example of Sanger sequencing of IDH1 gene in CN-AML: upper lane; wild-type IDH1 codon 132 (CGT), middle lane; mutant IDH1 R132H (CAT), lower lane; mutant IDH1 R132C (TGT)

Clinical features of IDHR132 mutated AML cases: Demographic, clinical and laboratory features of both patients’ groups are summarized in Table 1. There was no significant difference in demographic and clinical features between both patients’ groups apart from age that was significantly higher within mutated group than in wild group (p = 0.042). As regards CBC, there was statistically significant lower platelet count noticed in wild IDH1 than in mutant patients’ groups (p = 0.01). Both WBCs count and percentage of BM blasts were higher in wild IDH1 than in mutant IDH1 groups but without statistical significance.

Morphological features of AML with IDH1 R132 mutations: We studied the morphological pattern of AML according to French–American–British (FAB) classification in both patients’ groups (Table 1). The most common FAB subtypes noticed in the mutated IDH1 patients were M2 (5/9, 55.6 %) followed by M4 (3/9, 33.3 %) while M1 subtype was found only in one patient. None of this patient’s group had M0, M5, or M6. On the other hand, the most frequent FAB subtypes found in the wild IDH1 group were M4 (14/41, 34.1 %) followed by M5 (12/41, 29.3 %).

IDH1R132 Mutation and Response to Induction Therapy

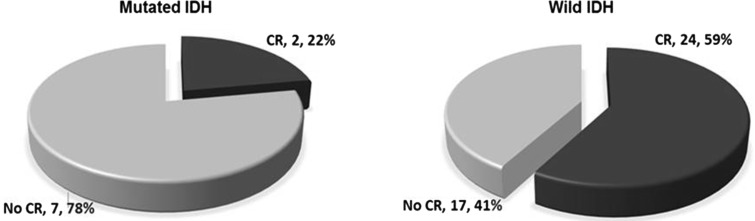

Among our CN-AML patients, 26/50 (52 %) achieve CR. CR rate was significantly higher in patient with wild IDH1 (24/41, 59 %) than in patients with mutated IDH1 (2/9, 22 %) with p value = 0.06 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Rate of complete remission in mutated is lower than wild IHD; p = 0.06

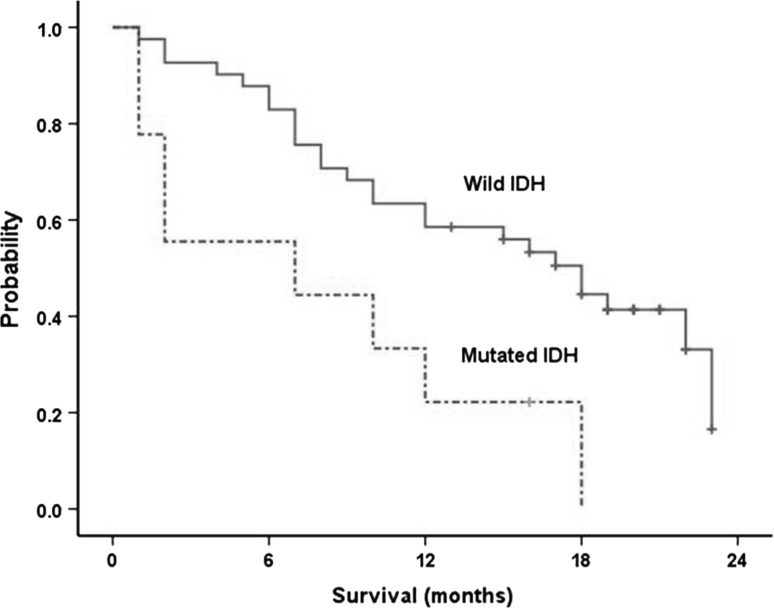

IDH1R132 Mutation and OS

After a median follow up of 16 months (95 % CI, 6–23 months), 33 patients were dead (66 %), and 17 patients were alive (34 %). The median OS was 15 months (95 % CI 10–21 months). The median OS was significantly longer in cases with wild IDH (18 months; 95 % CI 11–22 months) than mutated cases (7 months; 95 % CI 1–20 months); p = 0.009 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Overall survival of wild IDH and mutated IDH cases (median 18 vs. 7 months respectively log rank 6.7; p = 0.009)

IDH1R132 Mutation and Its Prognostic Impact

To assess the prognostic significance of IDH1R132 on OS, univariate analysis of different prognostic variables was done. We found that IDH1R132 could be a bad prognostic marker for OS as well as old age, low PS and higher BM blasts (p = 0.01, 0.04, 0.02, 0.01 respectively) (Table 2). In multivariate analysis, only PS and IDH1 mutation found to have independent significant prognostic impact on the OS of studied patients (p = 0.04 and 0.05 respectively) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of the effects of prognostic variables on OS

| Variables | Median OS (months) | p value* | Hazard ratio | 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median cut-off) | ||||

| ≤44a | 17 | 0.043 | 1.61 | 1.2–5.6 |

| >44 | 11 | |||

| FAB classification | ||||

| M1 | 14 | 0.8 | – | – |

| M2 | 15 | |||

| M4 | 19 | |||

| M5 | 16 | |||

| M6 | 13 | |||

| PS (ECOG) | ||||

| 1a | 18 | 0.02 | 3.50 | 1.07–11.91 |

| 2–3 | 9 | |||

| Hb, gm/dl (median cut-off) | ||||

| ≤8.6 | 16 | 0.43 | 1.11 | 0.82–5.6 |

| >8.6a | 13 | |||

| WBCs, ×103/µl (median cut-off) | ||||

| ≤28.6a | 17 | 0.14 | 1.81 | 0.92–5.6 |

| >28.6 | 13 | |||

| Platelets, ×103/µl (median cut-off) | ||||

| ≤72 | 16 | 0.62 | 1.89 | 0.45–5.6 |

| >72a | 15 | |||

| BM blasts, % (median cut-off) | ||||

| ≤53a | 17 | 0.013 | 2.26 | 1.2–11.6 |

| >53 | 11 | |||

| IDH1R132 | ||||

| Mutated | 7 | 0.009 | 4.54 | 1.17–19.65 |

| Wilda | 18 | |||

aReference group

OS Overall survival, CI confidence interval, FAB French–American–British classification, PS performance status, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Hb Hemoglobin, WBCs white blood cell counts, BM bone marrow, IDH1 Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1

*Significant p values are shown in bold

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the effects of prognostic variables on OS

| Variables | p value* | Hazard ratio | 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (≤44a/>44 years) | 0.23 | – | – |

| PS (ECOG) (1a/2–3) | 0.04 | 2.5 | 1.12–9.83 |

| BM blasts (≤53a/>53) | 0.41 | – | – |

| IDH1R132 (Wilda/Mutated) | 0.05 | 3.14 | 1.61–16.41 |

aReference group

CI Confidence interval, PS performance status, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, BM bone marrow, IDH1 Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1

*Significant p values are shown in bold

Discussion

CN-AML constitutes approximately 50 % of patients with AML and is considered a separate entity according to WHO classification of hemato-lymphoid malignancies. Many recurring mutations in genes such as FLT3, NPM1, CEBPA, WT1 and MLL have been identified during last 15 years and showed prognostic significance in CN-AML. These markers are not mutually exclusive and combination of them may further help in prediction of the adverse prognosis rather than relying on a single marker. For example, patients who carry an NPM1 mutation but not an FLT3 ITD are in the molecular low risk and carry better prognosis and outcome than patients who lack NPM1 [16]. In approximately 15–20 % of CN-AML patients, no mutations have been identified and the genetic alterations contributing to leukemogenesis and defining molecular risk for those patients are still undiscovered [17]. IDH1 mutation was discovered firstly in glioma and predict favorable outcome in these patients [18]. By performing whole genome sequencing for cases with CN-AML, Mardis et al. reported that IDH1R132 mutations can be found in patients with this disease [8].

Due to the limited data as regards this mutation in Egyptian patients with CN-AML, we aimed in our study to assess the prevalence of IDH1R132 in Egyptian CN-AML patients and to study its correlation with different clinical and laboratory findings. Furthermore, we intended to detect its prognostic impact on such patients.

The mutation in the IDHR132 was detected in 9/50 of our CN-AML patients (18 %). This prevalence is higher than that recorded by many previous studies [12, 19, 20] that ranged from 8 to 12.2 % of CN-AML patients. However, this was in concordance to Mardis et al. [8] who disclosed that the frequency of IDH1 mutation within his CN-AML subgroup of patients is 16 %. Furthermore, A recent study was done on Egyptian AML patients and it stated that 13 % of these patients are positive for this mutation [21]. Of note, this mentioned study was done on AML patients regardless the cytogenetic status and it has been demonstrated that IDH1 mutation is preferentially found in CN-AML [8, 19, 22]. The discrepancy in the prevalence rate across studies could be attributed to many causes. Different study designs is one of these causes; some researchers worked on patients with AML regardless the cytogenetic status or the cause for AML while others included only the CN-AML patients or were restricted to primary AML. Another cause that may play a major role in the difference of IDH mutation frequency is the racial background. For example, Kang et al. [23] did not detect a single case with IDH mutation in a series of 100 Korean AML patients. Also Guan et al. [22] detected only 1.1 % of his Chinese AML patients with IDHR132 mutation. Of interest, Mardis et al. [8] also found a difference in the IDH1 mutation frequency between white (8.5 %), black (6.7 %) and other races (10 %). Lastly, the methods of detection of IDH mutation in different studies have different sensitivities that reflect on the mutation frequencies.

Most of studies considered the prevalence and prognosis of this mutation in AML patient, only few studies paid attention to the clinical features and laboratory findings in these patients. The age of patients with IDHR132 mutation was significantly higher than those without the mutation in our study (p = 0.042). This finding is partially in accordance with previous publications that showed non-significant higher age within the IDH1 mutated AML patients [8, 12]. Alternatively, other studies showed a non-significantly lower age within the IDH1 mutated AML patients [21, 22].

Our patients with wild IDH1R132 gene show statistically significant lower platelet count than that found in mutated patients (p = 0.01). This finding was agreed by most of the previously published studies [12, 21, 22]. Both WBCs count and of BM blasts were non significantly higher in wild IDH1 than in mutant IDH1 groups in our study. Many of the earlier researches agreed with our results concerning the WBCs count [12, 19, 22]. On the other hand, the higher percentage of BM blasts in our wild IDH1 patient group was not in accordance with Patel et al. [19] and Elsayed et al. [21] who detected non significantly higher blast count in the mutated patients. Wagner et al. [12] demonstrated similar BM blast percentages in both mutated and non-mutated AML patients.

Our study shows that the most common morphological FAB classification associated with mutated IDHR132 is AML-M2 (55.6 %) followed by M4 (33.3 %) and M1 (11.1 %). None of the M5 and M6 cases show this mutation (Table 1). The predominance of M2 FAB subtypes in our study is agreed by most of the previous studies [19, 21, 22]. However, these studies differ from ours in the rest of the FAB subtype order. This could be attributed to their different patient group; as they included AML patients regardless the cytogenetic state. Nevertheless, Wagner et al. [12] results were in complete concordance with ours in this aspect. Of note, there patients were mainly composed of CN-AML (only 2/275 patients were with abnormal karyotype).

We aimed in our study to assess the prognostic impact of IDH1R132 mutation on our patients’ outcome. Within the nine patients with IDH1R132 mutation, only two respond to therapy and achieve CR. This finding implicates IDH1 mutation as bad prognostic factor on patient outcome that was agreed by some earlier studies [21, 24]. On other hand, other study shows that IDH1R132 mutation does not affect CR rate on such patients [12]. This discrepancy might explained by variable effect of different therapeutic protocols across the studies. For example, it has been proposed that repeated courses of high doses cytarabine improve the prognosis of patients with RAS mutations [25] and WT1 mutations [7]. The same might be true for IDH1R132 mutation. In addition the presence of other gene mutations in our study was not excluded (NPM1, FLT3, WT1 and other mutations) that may affect the patients’ response to therapy.

The median OS was significantly longer in cases with wild IDH (18 months; 95 % CI 11–22 months) than mutated cases (7 months; 95 % CI 1–20 months); p = 0.009 (Fig. 3). In univariate analysis of different prognostic variables, IDH1R132 found to be a bad prognostic indicator for OS as well as old age, low PS and higher BM blasts (p = 0.01, 0.04, 0.02, 0.01 respectively) (Table 2). Moreover, in multivariate analysis, only IDH1 mutation and PS found to have independent significant prognostic impact on the OS of our studied patients (p = 0.05 and 0.04 respectively) (Table 3).

The data on the impact of IDH1 mutations on the OS in AML patients are conflicting. Different studies, comprised of large patient cohorts, have shown that IDH1 mutations (with it most common form; IDH1R132) are associated with a worse prognosis, a better prognosis or have no association at all. It appears likely that the impact of IDH1 mutations on OS may depend on the specific patient population. For example, one study shows that patients with IDH1 mutations had a better OS if they had simultaneous NPM1 mutations carried [26]. On the other hand, results from other studies demonstrated that IDH1 mutations carry a worse prognosis in CN-AML, which was observed in patients with NPM1 mutations as well [8, 27, 28]. Another study reported that IDH1/2 mutations overall are not prognostic for OS, although the IDH1R132 mutation specifically is associated with a worse OS [29]. Wagner et al. found that IDH1R132 mutations did not have an impact on survival. According to these mentioned results, we can say that the impact of IDH1 mutations on clinical outcome of AML remains unclear due to the substantial differences in the study designs, patient groups, and treatment protocols.

In summary, our study reveals that IDH1R132 mutation occurs in a considerable percentage of Egyptian CN-AML patients that shows independent bad prognostic impact on the clinical outcome. Further studies on larger CN-AML patient cohort with more detailed molecular profile data are needed to confirm both its prevalence and prognostic impact in the presence of other gene mutations. This will help in stratifying patients for more intensive therapy. Furthermore, more studies are required to clarify the exact pathogenic role that may be used to generate a targeted therapy for patients with this mutation.

References

- 1.Ferrara F, Palmieri S, Leoni F. Clinically useful prognostic factors in acute myeloid leukemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66(3):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaidzik V, Dohner K. Prognostic implications of gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics. Semin Oncol. 2008;35(4):346–355. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scholl S, Fricke HJ, Sayer HG, Hoffken K. Clinical implications of molecular genetic aberrations in acute myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135(4):491–505. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, Alcalay M, Rosati R, Pasqualucci L, et al. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(3):254–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frohling S, Schlenk RF, Breitruck J, Benner A, Kreitmeier S, Tobiset K, et al. Prognostic significance of activating FLT3 mutations in younger adults (16 to 60 years) with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: a study of the AML Study Group Ulm. Blood. 2002;100(13):4372–4380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frohling S, Schlenk RF, Stolze I, Bihlmayr J, Benner A, Kreitmeier S, et al. CEBPA mutations in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: prognostic relevance and analysis of cooperating mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):624–633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaidzik VI, Schlenk RF, Moschny S, Becker A, Bullinger L, Corbacioglu A, et al. Prognostic impact of WT1 mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a study of the German-Austrian AML Study Group. Blood. 2009;113(19):4505–4511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Chen K, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balss J, Meyer J, Mueller W, Korshunov A, Hartmann C, von Deimling A. Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116(6):597–602. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ducray F, Marie Y, Sanson M. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21):2248–2249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc090593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson CB. Metabolic enzymes as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):813–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0810213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner K, Damm F, Gohring G, Görlich K, Heuser M, Schäfer I, et al. Impact of IDH1 R132 mutations and an IDH1 single nucleotide polymorphism in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: SNP rs11554137 is an adverse prognostic factor. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(14):2356–2364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.6899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou WC, Hou HA, Chen CY, Tang JL, Yao M, Tsay W, et al. Distinct clinical and biologic characteristics in adult acute myeloid leukemia bearing the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation. Blood. 2010;115(14):2749–2754. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tharapel AT. ISCN-1995—guidelines for in situ-hybridization nomenclature. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;77(1–2):37-37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanson M, Marie Y, Paris S, Idbaih A, Laffaire J, Ducray F, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 codon 132 mutation is an important prognostic biomarker in gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(25):4150–4154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mrozek K, Marcucci G, Paschka P, Whitman SP, Bloomfield CD. Clinical relevance of mutations and gene-expression changes in adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics: are we ready for a prognostically prioritized molecular classification? Blood. 2007;109(2):431–448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, Burnett AK, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European Leukemia Net. Blood. 2010;115(3):453–474. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321(5897):1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel KP, Ravandi F, Ma D, Paladugu A, Barkoh BA, Medeiros LJ, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with IDH1 or IDH2 mutation: frequency and clinicopathologic features. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135(1):35–45. doi: 10.1309/AJCPD7NR2RMNQDVF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez-Mercado M, Yip BH, Pellagatti A, Davies C, Larrayoz MJ, Kondo T, et al. Mutation patterns of 16 genes in primary and secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with normal cytogenetics. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e42334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elsayed GM, Nassar HR, Zaher A, Elnoshokaty EH, Moneer MM. Prognostic value of IDH1 mutations identified with PCR-RFLP assay in acute myeloid leukemia patients. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2014;26(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan L, Gao L, Wang L, Li M, Yin Y, Yu L, et al. The frequency and clinical significance of IDH1 mutations in chinese acute myeloid leukemia patients. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang MR, Kim MS, Oh JE, Kim YR, Song SY, Seo SI, et al. Mutational analysis of IDH1 codon 132 in glioblastomas and other common cancers. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(2):353–355. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Wei H, Wang M, Huai L, Mi Y, Zhang Y, et al. Some novel features of IDH1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia revealed in Chinese patients. Leuk Res. 2011;35(10):1301–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neubauer A, Maharry K, Mrozek K, Thiede C, Marcucci G, Paschka P, et al. Patients with acute myeloid leukemia and RAS mutations benefit most from postremission high-dose cytarabine: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(28):4603–4609. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel JP, Gonen M, Figueroa ME, Fernandez H, Sun Z, Racevskis J, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1079–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paschka P, Schlenk RF, Gaidzik VI, Habdank M, Krönke J, Bullinger L, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia and confer adverse prognosis in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation without FLT3 internal tandem duplication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(22):3636–3643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravandi F, Patel K, Luthra R, Faderl S, Konopleva M, Kadia T, et al. Prognostic significance of alterations in IDH enzyme isoforms in patients with AML treated with high-dose cytarabine and idarubicin. Cancer. 2012;118(10):2665–2673. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koszarska M, Bors A, Feczko A, Meggyesi N, Batai A, Csomor J, et al. Type and location of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations influence clinical characteristics and disease outcome of acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(5):1028–1035. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.736981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]