Abstract

Enteric pathogens from biofertilizer can accumulate in the soil, subsequently contaminating water and crops. We evaluated the survival, percolation and leaching of model enteric pathogens in clay and sandy soils after biofertilization with swine digestate: PhiX-174, mengovirus (vMC0), Salmonella enterica Typhimurium and Escherichia coli O157:H7 were used as biomarkers. The survival of vMC0 and PhiX-174 in clay soil was significantly lower than in sandy soil (iT90 values of 10.520 ± 0.600 vs. 21.270 ± 1.100 and 12.040 ± 0.010 vs. 43.470 ± 1.300, respectively) and PhiX-174 showed faster percolation and leaching in sandy soil than clay soil (iT90 values of 0.46 and 2.43, respectively). S. enterica Typhimurium was percolated and inactivated more slowly than E. coli O157:H7 (iT90 values of 9.340 ± 0.200 vs. 6.620 ± 0.500 and 11.900 ± 0.900 vs. 10.750 ± 0.900 in clay and sandy soils, respectively), such that E. coli O157:H7 was transferred more quickly to the deeper layers of both soils evaluated (percolation). Our findings suggest that E. coli O157:H7 may serve as a useful microbial biomarker of depth contamination and leaching in clay and sandy soil and that bacteriophage could be used as an indicator of enteric pathogen persistence. Our study contributes to development of predictive models for enteric pathogen behavior in soils, and for potential water and food contamination associated with biofertilization, useful for risk management and mitigation in swine digestate recycling.

Keywords: swine digestate, clay and sandy soils, biofertilization, biomarkers, management

Introduction

Global demand for fertilizer nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, is expected to reach 200,500,000 tons by 2018, and food demand for human consumption and livestock feed is expected to increase by 60–110% by 2050. Food production sustainability is therefore essential, and will require nutrient and water recycling under appropriate conditions of health and safety (Tilman et al., 2001; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2014). Swine manure is biomass suitable for biogas production in anaerobic biodigesters (AB) and the final digestate is used as agricultural biofertilizer. Digestate recycling is ecologically and economically viable, because it can simultaneously biofertilize and irrigate various crops, such as maize, wheat, and soybean, satisfying some or even all nitrogen and phosphorus requirements (Hansen et al., 1998; Topp et al., 2009).

Human and animal diseases associated with soil can be caused by exposure to or ingestion of indigenous pathogens of the normal soil microbiota, food contaminated with enterotoxins and neurotoxins, or enteric pathogens from human or animal excreta (Santamaría and Toranzos, 2003). Swine digestate can contain high levels of enteric pathogens that may contaminate soil, water, and foods (Khetsuriani et al., 2006; Topp et al., 2009). Its use in agriculture is therefore an issue for global “One Health” as it may affect humans and animals and, indeed, the environment more generally. The enteric pathogens present in biofertilizers can accumulate in soil (Gerba and Smith, 2005). Microbial models can be used to assess the behavior of enteric pathogens, including their survival, flow, propagation, leaching, percolation, and inactivation (Langlet et al., 2008; Boudaud et al., 2012). Bacteriophages, such as somatic coliphages (e.g., PhiX-174), f-specific RNA phages (e.g., MS2), and mengovirus (vMC0) have been used as models for human and animal enteric viruses (Langlet et al., 2008; Boudaud et al., 2012). Similarly, enteric bacteria, particularly coliform and Salmonella ssp., are widely used as biomarkers of fecal contamination. Salmonella is one of the most prevalent bacterial pathogens; it is zoonotic and has high survival rates in environment (Griffith et al., 2006; Venglovsky et al., 2006; European Food Safety Authority, and European Centre for Disease Prevention, and Control, 2015).

There have been few rigorous analyses of how enteric microorganisms behave in soil after being introduced by biofertilization, or of rates of environmental survival and propagation, leaching and percolation in different types of soil. Such analyses are required before swine-derived biofertilizers can be widely exploited agriculturally. The movement of enteric bacteria through soils, and the percolation of microorganisms in soils more generally, depend largely on the water saturation state (Artz et al., 2005). European Regulation (EC) 1069/2009, addressing health aspects of animal by-products and derived products not intended for human consumption, requires that Salmonella spp. to be below the detection threshold (25–50 g samples of biofertilizer scoring negative) and fewer than 1000 E. coli CFU g-1 of wet weight of biofertilizer (EC, 2009). In some countries, for example Brazil, there are no specific domestic or international rules for recycling animal by-products (Kunz et al., 2009). There is an evident need for the rigorous assessment of the fate of important enteric microorganisms after biofertilization of different types of soils. The development of appropriate bio-models for diverse environmental scenarios (survival, percolation, and leaching) would be valuable. However, there are currently no reports in the literature suggesting models that could be used to investigate the stability, percolation, and leaching of enteric pathogens, simultaneously. There has also been no comparison of the behaviors of enteric viruses and bacteria in sandy and clay soils in ex situ studies.

We aimed to (i) evaluate the survival and percolation of several major enteric microorganisms and to (ii) select the most suitable enteric microorganisms to serve as biomarkers of percolation and leaching after biofertilization with swine digestate. We spiked swine digestate with several model microorganisms (PhiX-174, vMC0, Salmonella enterica Typhimurium and E. coli O157:H7) and applied samples to clay and sandy soils. We then evaluated survival, percolation and leaching of the added microorganisms.

Materials and Methods

Swine Digestate and Soil

Digestate from mesophilic AB (35 ± 2°C) was collected from a pig farm in Salamanca, Spain. Clay and sandy soil were collected in agriculture fields, in Valladolid, Spain, that were not cultivated. Physicochemical characteristics of the swine effluent and soils were determined: chemical oxygen demand (COD), total solid (TS), nitrogen (TN) and phosphorus (TP) and pH for swine effluent; and texture, TN, organic carbon (OC) and matter (OM), carbonate, total carbon (TC), extractable sodium (ES), potassium (EP), calcium (EC), and magnesium (EM), percentage of clay and sand, pH and conductivity for soils according to APHA (2002) (Table 1). The OM, TC, EP, EC, EM, pH, and conductivity were all significantly higher in clay soil than in sandy soil.

Table 1.

Physicochemical characteristics of clay and sandy soil used in this study before and after biofertilization, and of the digestate used for biofertilizationa.

| Before biofertilization |

After biofertilization |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay soil | Sandy soil | Clay soil | Sandy soil | |

| TN (%) | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.11 | 0.08 ± 0.04 |

| OC (%) | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 1.45 ± 0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.03 |

| OM (%) | 1.16 ± 0.09∗ | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 2.57 ± 0.06 | 0.71 ± 0.02 |

| Carbonate (%) | <3.00 | <3.00 | <3.00 | <3.00 |

| TC (%) | 0.82 ± 0.05∗ | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 1.23 ± 0.15 | 0.32 ± 0.01 |

| ES (mg g-1) | <0.02 | <0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| EP (mg g-1) | 0.34 ± 0.05∗ | 0.033 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| EC (mg g-1) | 2.37 ± 0.15∗ | <1.60 | 6.39 ± 1.20∗ | <1.60 |

| EM (mg g-1) | 0.23 ± 0.01∗ | <0.08 | 0.73 ± 0.09 | <0.08 |

| Clay (%) | 32.2 ± 0.20∗ | 2.1 ± 0.41 | 34.8 ± 0.30 | 3.41 ± 0.10 |

| Sand (%) | 12.0 ± 1.25∗ | 95.50 ± 1.41 | 13.0 ± 1.40 | 94.0 ± 1.47 |

| pH | 8.33 ± 0.85∗ | 6.71 ± 0.55 | 8.62 ± 0.40 | 6.71 ± 0.02 |

| Conductivity (mS/cm) | 97.00 ± 3.20∗ | 12.21 ± 1.10 | 282.32 ± 4.10 | 114.3 ± 0.12 |

| Swine effluent from mesophilic anaerobic biodigesters (AB) | ||||

| Total COD (mg L-1) | 42,246 ± 375 | |||

| TS (mg L-1) | 32,130 ± 267 | |||

| TN (mg L-1) | 5,936 ± 380 | |||

| TP (mg L-1) | 523 ± 43 | |||

| pH | 7.30 ± 0.20 | |||

aMean ± Standard deviation.

∗Significant difference (p < 0.05).

Model Microorganisms

Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain CECT 4267, S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain ATCC 14028, the avirulent genetically modified mengovirus strain M (vMC0) ATCC VR-1597, and PhiX-174 were used as model enteric pathogens. Bacterial stocks were prepared in nutrient broth, for 14 h at 37°C, as described by Magri et al. (2013). PhiX-174 was propagated in the host E. coli strain ATCC 13706 as described by International Organization For Standardization [ISO] 10705-2:2000 (2000) and vMC0 stocks were prepared from an infected HeLa cell line (ATCC CCL-2TM). Cells were cultivated in six-well tissue culture plates at a density of 3.0 × 106 cells/mL and were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h with vMC0 stocks, as described by Costafreda et al. (2006).

Salmonella enterica Typhimurium was counted using the method of Magri et al. (2013) and E. coli by the ISO 4832:2006 method. Colonies were counted and the results are expressed in colony forming units (CFU). PhiX-174 was titred in agar on E. coli ATCC 13706, by the double agar layer method (International Organization For Standardization [ISO] 10705-2:2000, 2000). Plaques were counted and the results are expressed in plaque forming units (PFUs). Infectious vMC0 was titred by plaque assay (PA), as described by Ernest et al. (1970). For PA, briefly, 1 mL or g of sample was treated with 10 U/mL penicillin, 10 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.025 μg/mL amphotericin B and diluted with 9 mL of saline buffer and 0.25 mL samples used to inoculate HeLa cells. HeLa cells were cultivated in six-well tissue culture plates at a density of 3.0 × 106 cells/well and were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. Inoculated cells were plated and incubated at 37°C for 5–7 days. The plaques were counted macroscopically and the results are expressed in PFUs.

Preparation and Analysis of Microcosms of Biofertilized Soils

Microbial Survival Assay

We studied the survival of the model enteric microorganisms over 120 days in biofertilized clay and sandy soils. All experiments were performed in triplicate using sentinel chambers, as described by Schwarz et al. (2014). Sentinel chambers were constructed using 3.5 mL tubes with pore sizes of 0.2 μm (Life Sciences, New York, NY, USA) and membrane lids (Eppendorf Lid-Bac membrane lids, Eppendorf, Germany) to close the top of the columns. The pore size and electric charge was sufficiently large to allow exchange of gas and moisture without the loss of bacteria or viruses.

Biofertilized soils containing 7 log10 CFU g-1 and 5 log10 PFU g-1 of the model enteric bacteria and viruses, respectively, were used to fill sentinel chambers and placed vertically in clay and sandy soil microcosms (10–20 cm of depth) at 23 ± 2°C (environmental average temperature during the spring period, when soils are fertilized in agricultural practice). The amount of swine effluent used in the experiment mimicked that usually applied for corn and wheat crops (50 m3/hectare).

Soils samples were collected after: 1, 4, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, and 120 days. On each sampling date, two sentinel chambers were randomly selected for each soil microcosm, and evaluated. Inactivation was considered statistically significant if the count (or titre) declined by >2 log10 with p < 0.05 (ANOVA, GraphPad Prism 5.0, EUA). Also, iT90 values in soils were calculated until 120 days after biofertilization.

Microbial Percolation Assay

Polyvinyl chloride tubes (PVC tubes), 60 cm long and 30 cm in diameter, were closed with a cap at the bottom, and arranged horizontally in an air-conditioned environment (22 ± 2°C). The soils were placed in the tubes, in the same order they were removed from the farm (until 60 cm deep). All tubes were then placed vertically and were left undisturbed for a week to allow the soil to settle. Then, the top 4 cm of soil was discarded to provide space for the swine effluent (biofertilization). The clay soil density was 1.6 and the sandy soil 1.3 g cm-3. The soils in the PVC tubes were biofertilized by spraying with swine effluent from mesophilic AB containing 7 log10 CFU g-1 of the model enteric bacteria and 5 log10 PFU g-1 of the model viruses. All microorganisms were applied together, mimicking contamination in biofertilizers in practice. The amount of swine effluent used was equivalent to that usually applied for corn and wheat cultivation (50 m3/hectare).

Percolation of the enteric microorganisms was followed by collection of 1 g samples of soil at depths of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 cm by making holes of 1 cm in diameter in the PVC tubes using a sterile probe. Samples were collected 0, 0.12, 0.24, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, and 20 days after biofertilization.

The initial microbial concentration in layers 10 cm deep and the final concentration 50 cm deep were used to calculate percolation. The soil layers (10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 cm depths) were grouped according to the distribution of microorganisms over time, and the decimal reductions value (rT90 days) and decimal increase value (iT90 days) caused by the percolation action were calculated for each clay and sandy soil.

Microbial Leaching from Biofertilized Soils after Rain

For leaching assays, 120 days after biofertilization, the soil microcosms were subjected to 300 mm of rain (collected natural rain, 150 mm h-1, applied over 2h). A sterile collector tube, with capacity of 100 mL, was placed under the soil microcosms, horizontally, allowing the collection of leaching liquid (drained through a lower opening). Liquid drained from soils was collected 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after the rain and the enteric microorganisms counted.

Statistical Analysis

Nonparametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Kruskal–Wallis) in Statistic 7.0 was used to evaluate the differences in the physicochemical parameters of the soils. The times required for a 10-fold reduction in enteric microorganism counts by inactivation and enteric microorganism leaching from biofertilized soils were calculated considering linear or logarithmic regression curves. Statistical one-way ANOVA was used to evaluate differences between the groups, using a 95% confidence level, followed by the Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test, and Pearson’s correlation analysis was used as necessary (GraphPad Prism 5.0). The critical p-value for the test was set at ≤0.05.

Results

Survival of the Model Microorganisms

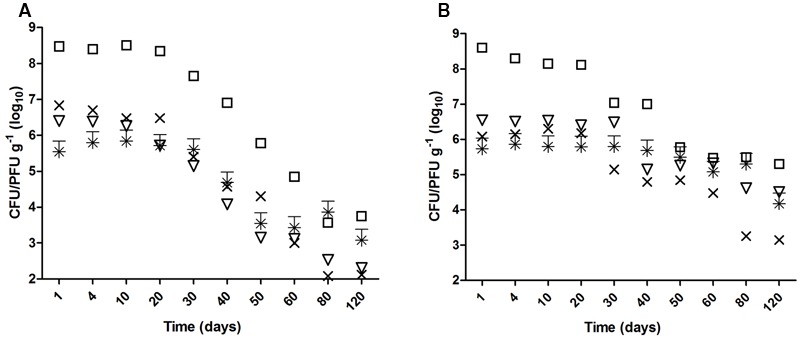

Escherichia coli O157:H7, S. enterica Typhimurium were significantly reduced (>2 log10; p < 0.05) after 40 days in biofertilized soil of both types (Figure 1). However, whereas the time for a significant reduction in clay soils was similar for the two viruses selected in this study (40 days for vMC0 and 50 days for PhiX-174), the times were longer in sandy soils (60 days for vMC0, and no significant reduction of PhiX-174 after 120 days) (Figure 1). Similarly, the iT90 values were higher in clay than in sandy soils for all the microorganisms (6.62 vs. 10.75 for E. coli O157:H7, 9.34 vs. 11.90 for S. enterica Typhimurium, 10.52 vs. 21.27 for vMC0, and 12.04 vs. 43.47 for PhiX-174) (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Survival of enteric microorganisms in biofertilized (A) clay and (B) sandy soil 120 days after biofertilization with contaminated swine digestate. (□) Escherichia coli O157:H7, (×) S. Typhimurium, (∗) PhiX-174, and (▽) vMC0.

Table 2.

Mean iT90 (decimal inactivation), inactivation coefficients (k), and multiple-correlation coefficients (r2) for soils after biofertilizationa.

| -k | iT90 days | r2 | -k | iT90 days | r2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clay soil |

Sandy soil |

|||||

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 | 0.151 ± 0.020∗1 | 6.620 ± 0.500 | 0.870 ± 0.040 | 0.093 ± 0.030 | 10.750 ± 0.900 | 0.880 ± 0.040 |

| S. Typhimurium | 0.0107 ± 0.030∗1 | 9.340 ± 0.200 | 0.990 ± 0.050 | 0.084 ± 0.020 | 11.900 ± 0.900 | 0.810 ± 0.050 |

| vMC0 | 0.095 ± 0.030∗2 | 10.520 ± 0.600 | 0.880 ± 0.020 | 0.047 ± 0.010 | 21.270 ± 1.100 | 0.930 ± 0.020 |

| PhiX | 0.083 ± 0.010∗2 | 12.040 ± 1.300 | 0.820 ± 0.030 | 0.023 ± 0.010 | 43.470 ± 1.300 | 0.840 ± 0.030 |

aMean ± Standard deviation.

∗Significant difference (p < 0.5). Natural number indicates the cluster.

Percolation of the Selected Model Microorganisms

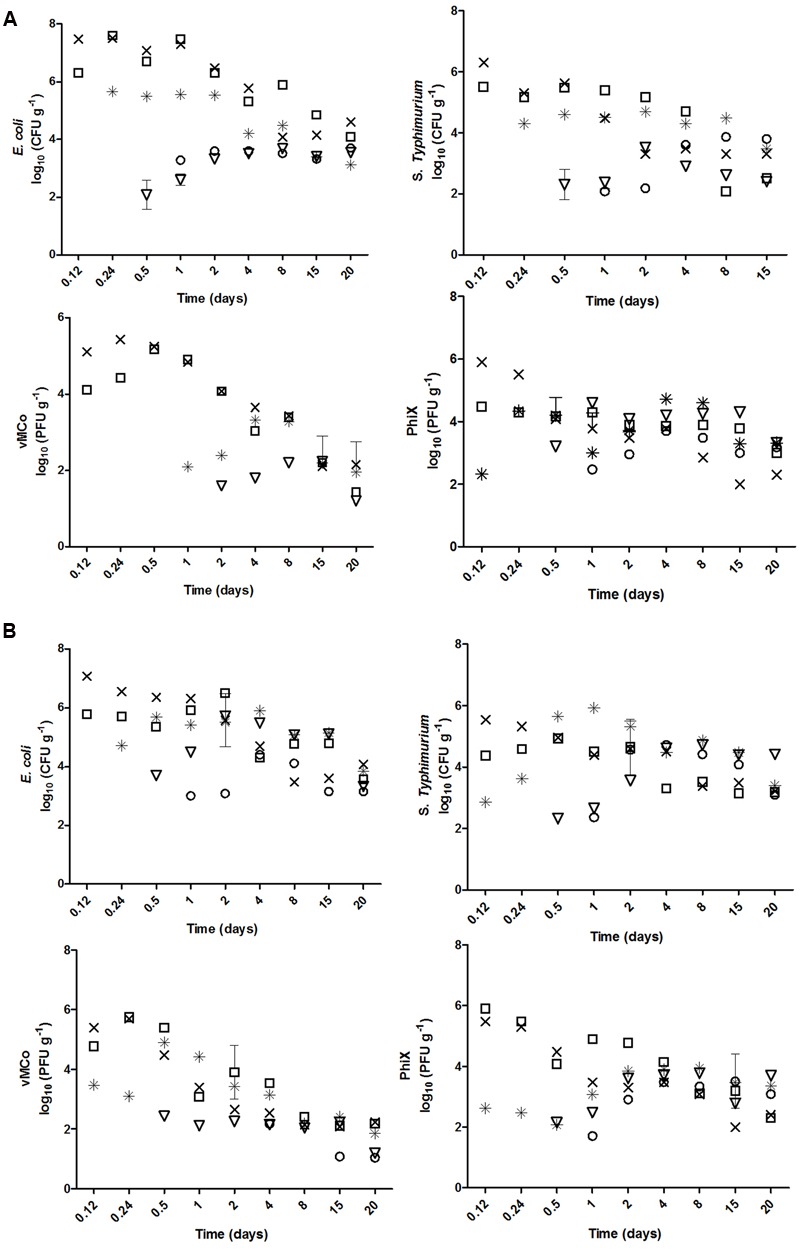

Significant percolation was observed for all four microorganisms and both soil types (Figure 2). The mean percolation was similar in the two types of soil for each microorganism: log10 3.80 vs. log10 3.92 for E. coli O157:H7, log10 2.60 vs. log10 2.45 for S. enterica Typhimurium, log10 4.2 vs. log10 4.2 for vMC0, and log10 2.8 vs. log10 2.32 for PhiX-174 in clay and sandy soils, respectively. E. coli O157:H7 and vMC0 percolated significantly more than the other two microorganisms in both soils (p < 0.05) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Percolation of E. coli O157:H7, S. Typhimurium, vMC0 and PhiX-174 (×) 10, (□) 20, (∗) 30, (▽) 40, and (○) 50 cm deep in biofertilized (A) clay and (B) sandy soil.

The percolation of the microorganisms from the more superficial (10, 20, and 30 cm) to the deeper (40 and 50 cm) layers was linear, whereas the increase of the concentration of microorganisms in the deeper layers (40 and 50 cm) was logarithmic. The percolation from the upper layers to the deeper ones was not significantly different for the four microorganisms (p > 0.05) in sandy soil, the percolation of PhiX-174 and E. coli O157:H7 were significantly slower and faster (p < 0.05), respectively, in clay soil (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean rT90 (decimal reductions) and iT90 (decimal increase) by percolation per day, respective coefficients (k) and multiple-correlation coefficients (r2) for clay and sandy soil after biofertilization.

| Group (cm) | K (days) | r2 | rT90 (days) | iT90 (days) | Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Clay soil | ||||||

| E. coli O157:H7 | 10–20 | 0.61 | 0.94 | 1.62 | – | Linear |

| 30–40–50 | 1.11∗1 | 0.76 | – | 0.90 | Logarithmic | |

| 30–40–50 | 2.35∗2 | 0.82 | – | 0.42 | Logarithmic | |

| S. Typhimurium | 10–20 | 0.57 | 0.92 | 1.73 | – | Linear |

| 30–40–50 | 0.60 | 0.76 | – | 1.64 | Logarithmic | |

| vMC0 | 10–20 | 0.41 | 0.95 | 2.84 | Linear | |

| 30–40–50 | 0.42 | 0.91 | – | 0.53 | Logarithmic | |

| PhiX | 10–20 | 0.27 | 0.95 | 3.58 | – | Linear |

| 30–40–50 | 0.41 | 0.72 | – | 2.43 | Logarithmic | |

| B. Sandy soil | ||||||

| E. coli O157:H7 | 10–20 | 0.47 | 0.91 | 2.12 | – | Linear |

| S. Typhimurium | 10–20 | 0.42 | 0.91 | 2.38 | – | Linear |

| 30–40–50 | 1.10 | 0.84 | – | 0.90 | Logarithmic | |

| vMC0 | 10–20 | 0.35 | 0.79 | 2.85 | – | Linear |

| 30–40–50 | 0.49 | 0.67 | – | 2.04 | logarithmic | |

| PhiX | 10–20–40 | 0.41 | 0.95 | 2.43 | – | Linear |

| 40–50 | 2.22† | 0.91 | – | 0.45 | Logarithmic |

∗Significant difference (p < 0.05). Natural number indicates the cluster.

†Significant difference (p < 0.05).

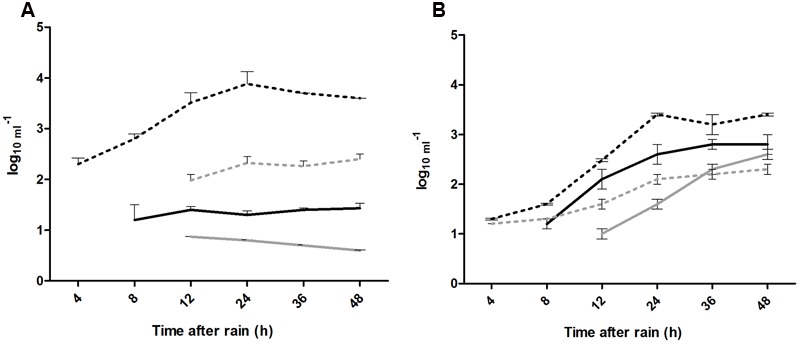

Leaching of the Selected Model Microorganisms

The leaching of the enteric bacteria (E. coli O157:H7 and S. enterica Typhimurium) over 48 h was higher in clay soils than in sandy soils (log10 3.81 vs. log10 2.80 and log10 2.24 vs. log10 1.90 per mL, respectively), whereas the leaching of the model viruses (vMC0 and PhiX-174) was much higher in sandy soil (log10 1.8 vs. log10 0.7 and log10 2.3 vs. log10 1.34 per mL, respectively) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

(A,B) Leaching of enteric microorganisms over 48 h following application of 300 mm of natural rain. ∗Significant difference (p < 0.05), where: (---) S. Typhimurium, (---) E. coli O157:H7, (-) vMC0, and (-) PhiX-174.

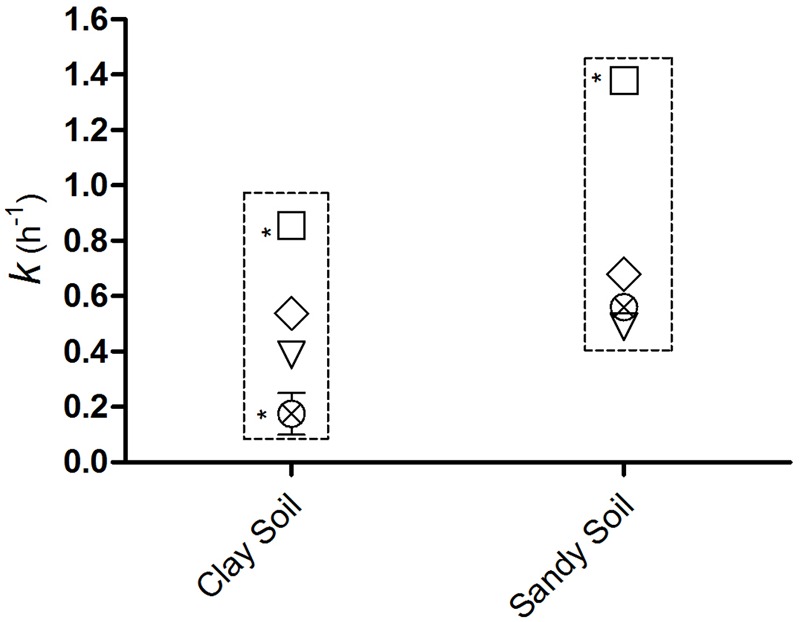

The coefficients of leaching (k h-1) were 0.85 for E. coli O157:H7, 0.53 for S. enterica Typhimurium, 0.38 vMC0 and 0.17 for PhiX-174 in clay soils, and 1.3, 0.68, 0.49, and 0.56, respectively, in sandy soils (Figure 4). The coefficients of leaching were higher in sandy soils for all four microorganisms, and higher for the two bacteria than the two viruses; the leaching of E. coli O157:H7 was significantly highest (p < 0.05) in both soils (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Coefficients of leaching (k h-1) of (□) E. coli O157:H7, (♢) S. Typhimurium, (⊗) PhiX-174, and (∇) vMC0 over 48 h following application of 300 mm of natural rain. ∗Significant difference (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Soil features, including temperature, pH, clay, organic matter, and salinity content, affect the survival, stability, percolation, and leaching of enteric pathogens present (Kimura et al., 2008). We investigated the survival and percolation of four relevant enteric microorganisms (two bacterial pathogens: E. coli O157:H7, and S. enterica Typhimurium and two viruses: PhiX-174, vMC0) in clay and sandy soils in a model of biofertilization with swine effluent from AB. E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella ssp. are major zoonotic enteric bacterial pathogens. Salmonella ssp. are often isolated from farmed pigs and poultry, which are the main reservoirs for human infections. These species show high survival rates in the environment (Griffith et al., 2006; Chen and Jiang, 2014). Somatic coliphages and vMC0 have been used as models for human and animal enteric viruses. PhiX-174 is stable across a range of temperatures, pHs and UV treatments, and vMC0 has been used as model of norovirus, and hepatitis A and E viruses (Costafreda et al., 2006; Rodríguez-Lázaro et al., 2012; Boudaud et al., 2012).

Soils are complex matrixes and some of the compounds present have antimicrobial (virucidal and/or bactericidal) properties when concentrated: examples include malic, lactic and butyric acids, proteases, nucleases, bacterial and fungal metabolites; there may also be microorganism predation (Wiesmann et al., 2007; Dika et al., 2011). The survival, percolation, and leaching of the four microorganisms we studied differed between the two soil types. However, microbial survival and leaching was significantly lower in clay soil than in sandy soil for all the four microorganisms. The organic matter and nutrient contents are higher in clay than sandy soil, and the pH more alkaline. The pH and salt concentration (salt increases conductivity) may directly affect the adsorption capacity of viruses. Increasing the concentration of cations, especially multivalent cations, increases the adsorption capacity, mainly for enteric viruses (Gerba, 1984; Gerba and Smith, 2005; Pepper et al., 2006). The leaching of nutrients is high on sandy soils with poor water retention capacity (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2010). PhiX-174 showed faster percolation and leaching from biofertilized sandy soil than clay soil. The isoeletric point of PhiX-174 is 6.5 (Schijven and Hassanizadeh, 2000) and the pH of clay and sandy soils studied was 8.6 and 6.7, respectively. Therefore, PhiX-174 may have aggregated in the clay soil, hindering its percolation and leaching, whereas this was unlikely to have been the cases in sandy soil.

We report that the survival of the model viruses was significantly longer and correspondingly that microbial inactivation was faster for bacteria (iT90 days). Bacteriophage PhiX-174 showed the least inactivation the highest iT90 value of the four microorganisms studied (Table 2 and Figure 1). PhiX-174 may therefore be useful as a biomarker for the study of persistence of enteric pathogens in soils. Enteric viruses can survive for long periods [DNA viruses like human adenovirus decay by only 90% in 180 days in biosolid-amended and un-amended soils (Schwarz et al., 2014)] particularly in soils with a higher moisture content (60–90 days in soils with 10% moisture content and 15–25 days in air-dried soil (Yeager and O’Brien, 1979).

All four microorganisms percolated significantly in both soil types. Thus, a proportion of the microorganisms applied at the surface can be transferred into deeper layers, and the reduction of microbial survival may be, in part, associated to this process. The percolation of the microorganisms was linear, but microbial accumulation in the deeper layers was logarithmic. S. enterica Typhimurium percolated and was inactivated more slowly than E. coli O157:H7, suggesting that it may readily remain in contact with vegetables of short roots, like lettuce. E. coli O157:H7 was both transferred to the deeper layers of both soils (i.e., percolation) and leached faster, raising the issue of contamination of surface and groundwater used for human supply and for plant irrigation. E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium are able to move through soil with water after rainfall or irrigation and can even reach the groundwater (Artz et al., 2005; Lang and Smith, 2007; Semenov et al., 2009). Field experiments showed that 20% of E. coli applied to fields in contaminated slurry was found in drain water (Vinten et al., 2002). Also, our study and previous results reveal the risk of internal contamination of plants by E. coli O157:H7 and other coliforms. In view of these observations, international regulations are surprisingly divergent about microbiological criteria for water for human consumption and irrigation (Chart, 2000; Semenov et al., 2009).

We show that E. coli O157:H7 has potential as a microbial biomarker for depth contamination and leaching in clay and sandy soils. Note that it is possible that genogroups of E. coli different from E. coli O157:H7 behave differently in these or other soils.

Conclusion

We report that survival, percolation, and leaching of enteric microorganisms in biofertilized soils depend on the characteristics of the microbes and the soil. Our findings corroborate previous work suggesting that pH, OM content, soil texture, and rainfall are the principal factors that affect the survival and leaching of microbial pathogens (Demoling et al., 2007). We believe that potential microbial contamination of surface and groundwater by leaching and percolation should be evaluated prior to swine digestate application in agriculture. Finally, our work shows that the bacteriophage PhiX-174 and the bacterial pathogen E. coli O157:H7 can be used as biomarkers for studies on microbial persistence and percolation and leaching, respectively. Our findings contribute to the development of predictive models of the behavior of enteric pathogens in different soils and of the potential transfer of pathogens to water and food by biofertilization. Such models would be useful for risk management and mitigation in swine digestate recycling.

Author Contributions

GF performed most of the experiments and help in the preparation of the manuscript. MG-G discussed the experiments, review the results and help in the preparation of the manuscript. MH discussed the experiments, supervise the experimental work and review the results and help in the preparation of the manuscript. AK review the experimental plan and the results. CB discussed the experiments, review the results and help in the preparation of the manuscript. DR-L designed the experiments, review the results, and prepare the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was financially supported by the RTA2014-00024-C04-01 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Innovation and the Brazilian CNPq Project number 472804/2013-8, and by CAPES/PNPD and CAPES/PDSE.

References

- APHA (2002). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater 22nd Edn. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Artz R. R. E., Townend J., Brown K., Towers W., Killham K. (2005). Soil macropores and compaction control the leaching potential of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Environ. Microbiol. 7 241–248. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00690.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudaud N., Machinal C., David F., Fréval-Le Bourdonnec A., Jossent J., Bakanga F., et al. (2012). Removal of MS2, Qβ and GA bacteriophages during drinking water treatment at pilot scale. Water Res. 15 2651–2664. 10.1016/j.watres.2012.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chart H. (2000). VTEC enteropathogenicity. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 29(Suppl.) S12–S13. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2000.tb05328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Jiang X. (2014). Microbiological safety of chicken litter or chicken litter-based organic fertilizers: a review. Agriculture 4 1–29. 10.3390/agriculture4010001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costafreda M. I., Bosch A., Pintó R. M. (2006). Development, evaluation, and standardization of a real-time TaqMan reverse transcription-PCR assay for quantification of hepatitis A virus in clinical and shellfish samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 3846–3855. 10.1128/AEM.02660-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demoling F., Figueroa D., Baath E. (2007). Comparison of factors limiting bacterial growth in different soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39 2485–2495. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2010). Fertiliser manual (RB209) 8th Edn. London: The Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Dika C., Duval J. F., Ly-Chatain H. M., Merlin C., Gantzer C. (2011). Impact of internal RNA on aggregation and electrokinetics of viruses: comparison between MS2 phage and corresponding virus-like particles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 4939–4948. 10.1128/AEM.00407-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EC (2009). REGULATION (EC) No 1069/2009 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 October 2009 laying down Health Rules as Regards Animal By-Products and Derived Products not Intended for Human Consumption and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1774/2002 (Animal by-products Regulation). Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:300:0001:0033:EN:PDF [Google Scholar]

- Ernest C., Borden G., William G., Jr., Frederick A. M. (1970). Comparison of agar and agarose preparations for mengovirus plaque formation. Appl. Microbiol. 20 289–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2015). The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2013. EFSA J. 13:3991 10.2903/j.efsa.2015.3991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO] (2014). The State of Food and Agriculture—Innovation in Family Farming. Rome: Food, and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 161. [Google Scholar]

- Gerba C. P. (1984). Applied and theoretical aspects of virus adsorption to surfaces. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 30 133–168. 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)70054-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerba C. P., Smith J. E., Jr. (2005). Sources of pathogenic microorganisms and their fate during land application of wastes. J. Environ. Qual. 34 42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith R. W., Schwartz K. J., Meyerholz D. K. (2006). “Salmonella,” in Diseases of Swine 9th Edn eds Straw B. E., Zimmerman J. J., D’Allaire S., Taylor D. J. (Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing; ) 739–751. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K. H., Angelidaki I., Ahring B. K. (1998). Anaerobic digestion of swine manure: inhibition by ammonia. Water Res. 32 5–12. 10.1016/S0043-1354(97)00201-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Organization For Standardization [ISO] 10705-2:2000 (2000). Water Quality – Detection and Enumeration of Somatic Coliphage. Geneva: International Organization For Standardization. [Google Scholar]

- Khetsuriani N., Lamonte-Fowlkes A., Oberst S., Pallansch M. A. (2006). Centers for disease control and prevention. enterovirus surveillance–United States, 1970-2005. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 55 1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M., Jia Z. J., Nakayama N., Asakawa S. (2008). Ecology of viroses in soils: past, present and future perspectives. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 54 1–32. 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2007.00197.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz A., Miele M., Steinmetz R. L. R. (2009). Advanced swine manure treatment and utilization in Brazil. Bioresour. Technol. 100 5485–5489. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang N. L., Smith S. R. (2007). Influence of soil type, moisture content and biosolids application on the fate of Escherichia coli in agricultural soil under controlled laboratory conditions. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103 2122–2131. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03490.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlet J., Gaboriaud F., Duval J. F. L., Gantzer C. (2008). Aggregation and surface properties of F-specific RNA phages: implication for zembrane filtration processes. Water Res. 2008 2769–2777. 10.1016/j.watres.2008.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magri M. E., Philippi L. S., Vinnerås B. (2013). Inactivation of pathogens in feces by desiccation and urea treatment for application in urine-diverting dry toilets. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 2156–2163. 10.1128/AEM.03920-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper I. L., Brooks J. P., Gerba C. P. (2006). Pathogens in biosolids. Adv. Agron. 90 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Lázaro D., Cook N., Ruggeri F. M., Sellwood J., Nasser A., Nascimento M. S., et al. (2012). Virus hazards from food, water and other contaminated environments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36 786–814. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00306.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría J., Toranzos G. A. (2003). Enteric pathogens and soil: a short review. Int. Microbiol. 6 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schijven J. F., Hassanizadeh S. (2000). Removal of viruses by soil passage: overview of modeling, processes, and parameters. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 30 49–127. 10.1080/10643380091184174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz K., Sidhu J. P. S., Pritchard D., Li Y., Toze S. (2014). Decay of enteric microorganisms in biosolids-amended soil under wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivation. Water Res. 59 185–197. 10.1016/j.watres.2014.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenov A. V., van Overbeek L., van Bruggen A. H. (2009). Percolation and survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in soil amended with contaminated dairy manure or slurry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 3206–3215. 10.1128/AEM.01791-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D., Fargione J., Wolff B., D’Antonio C., Dobson A., Howarth R., et al. (2001). Forecasting agriculturally driven global environmental. Science 292 281–284. 10.1126/science.1057544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp E., Scott A., Lapen D. R., Lyautey E., Duriez P. (2009). Livestock waste treatment systems for reducing environmental exposure to hazardous enteric pathogens: some considerations. Bioresour. Technol. 100 5395–5398. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venglovsky J., Martinez J., Placha I. (2006). Hygienic and ecological risks connected with utilization of animal manures and biosolids in agriculture. Livestock Sci. 102 197–203. 10.1016/j.livsci.2006.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinten A. J. A., Lewis D. R., Fenlon D. R., Leach K. A., Howard R., Svoboda I., et al. (2002). Fate of Escherichia coli and Escherichia coli O157 in soils and drainage water following cattle slurry application at 3 sites in Southern Scotland. Soil Use Manage. 18 223–231. 10.1111/j.1475-2743.2002.tb00243.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesmann U., Choi I. S., Dombrowski E. M. (2007). Fundamentals of Biological Wastewater Treatment. Weinheim: Willey-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; 355. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager J. G., O’Brien R. T. (1979). Enterovirus inactivation in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 38 694–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]