Abstract

The background and purpose of this paper is to investigate adherence, exercise performance levels and associated factors in head and neck cancer (HNC) patients participating in a guided home-based prophylactic exercise program during and after treatment [swallowing sparing intensity modulated radiation therapy (SW-IMRT)]. Fifty patients were included in the study. Adherence was defined as the percentage of patients who kept up exercising; exercise performance level was categorized as low: ≤1, moderate: 1–2, and high: ≥2 time(s) per day, on average. Associations between 6- and 12-week exercise performance levels and age, gender, tumour site and stage, treatment, intervention format (online or booklet), number of coaching sessions, and baseline HNC symptoms (EORTC-QLQ-H&N35) were investigated. Adherence rate at 6 weeks was 70% and decreased to 38% at 12 weeks. In addition, exercise performance levels decreased over time (during 6 weeks: 34% moderate and 26% high; during 12 weeks: 28% moderate and 18% high). The addition of chemotherapy to SW-IMRT [(C)SW-IMRT] significantly deteriorated exercise performance level. Adherence to a guided home-based prophylactic exercise program was high during (C)SW-IMRT, but dropped afterwards. Exercise performance level was negatively affected by chemotherapy in combination with SW-IMRT.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, (Chemo)radiation, Prophylactic exercises, Swallowing problems, Speech problems

Introduction

Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) targeting head and neck cancer (HNC) patients allows for more conformal dose distribution, aiming to minimize the dose to the surrounding healthy tissues and to spare normal structures (i.e. the parotid glands). Treatment with IMRT has proven to lead to less treatment-related side-effects, such as xerostomia, and to improved health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [1–12]. Attempts are made to also spare other organs at risk (OARs), such as the submandibular glands [13], and the swallowing structures [14]. Van der Laan et al. [1, 14] demonstrated that, compared with the standard IMRT, reduction of the dose to the swallowing OARs (SWOARs) has the potential to reduce the risk on swallowing problems through swallowing sparing IMRT (SW-IMRT). It is hypothesized that patients should be encouraged to maintain oral intake and to perform exercises to promote the use of the muscles in the head and neck area. The ongoing use of the swallowing, speech, and shoulder mechanisms during and after treatment may enhance the potential benefits of SW-IMRT [15, 16]. Therefore, we developed a guided home-based prophylactic exercise program ‘Head Matters’ to maintain muscle structure and swallowing, speech, and shoulder function (HM) [17]. Offering HNC patients such a prophylactic exercise program may delay the decline of lean muscle mass in the head and neck area, and may limit the extent of post-treatment impairment [15, 18–29], eventually leading to improved HRQOL [15, 16, 21–27, 30]. The current literature on prophylactic exercise programs varies considerably in terms of timing, intensity, duration, frequency, and type of exercise. In addition, a broad range (13–71%) of adherence rates has been reported [17, 21, 25, 31–33]. However, information on patient’s adherence to home-based exercise programs, on data collected related to daily exercise performance, and on factors that could potentially influence patient’s exercise performance is lacking. How realistic an approach is regarding home-based exercise programs in HNC patients during SW-IMRT is unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study was (1) to investigate adherence to a 12-week home-based exercise program during SW-IMRT, (2) to investigate exercise performance levels, (3) to investigate whether demographic and clinical factors, or HNC-specific HRQOL at baseline is associated with exercise performance levels, and (4) to investigate whether exercise performance levels are associated with the course of HNC-specific HRQOL during the entire 12-week exercise program.

Materials and methods

Design

A prospective clinical cohort study.

Patients

Between 2011 and 2013, HNC patients were included in this study if they were planned for SW-IMRT at VU University Medical Center (VUmc), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Patients fulfilled the following criteria: (1) age ≥ 18 years, (2) cancer originating in the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, or larynx, (3) SW-IMRT alone or in combination with chemotherapy [(C)SW-IMRT], (4) performance status 0–2 on the World Health Organization Scale [34], (5) the absence of severe cognitive impairment, and (6) sufficient mastery of the Dutch language (criteria 4–6 as judged by the radiation oncologist who included the patients in this study). Patients who previously underwent surgery, radiotherapy, or chemoradiation, who had prior malignancies in the head and neck area, and/or distant metastases were excluded. Patients with physician-rated RTOG grade 2–4 swallowing dysfunction at baseline (1 = mild fibrosis, slight difficulty in swallowing solids, no pain in swallowing; 2 = unable to take solid food normally, swallowing semi-solid food; 3 = severe fibrosis, able to swallow only liquids, may have pain in swallowing; 4 = necrosis, complete obstruction) (according to the RTOG/EORTC Late Radiation Morbidity Scoring Schema [35]) were also excluded to ensure that the observed swallowing dysfunction was induced by radiation treatment itself and not by tumour extension.

Patients were treated with curative intent using (C)SW-IMRT. In all patients, parotid glands and swallowing structures were spared when possible, without compromising the dose to the target volumes. A simultaneous integrated boost technique was used with bilateral elective irradiation of the neck nodes to a total dose of 57.75 Gy, using a dose per fraction of 1.65 Gy. The primary tumour and pathological lymph nodes were treated to a total dose of 70 Gy, in fractions of 2 Gy. Chemotherapy was given concurrently with radiotherapy and consisted generally of cisplatin 100 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 22, and 43.

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Intervention

The guided home-based exercise program Head Matters (HM) was developed by speech and swallowing therapists, physiotherapists, head and neck surgeons, and radiation oncologists. HM was based on the previous research [15, 16, 19–30] and on clinical practice. HNC patients were recommended to perform HM exercises for at least 15 min per day in total. HM is comprised of the following prophylactic exercises: (1) exercises to maintain mobility of the head, neck, and shoulders (e.g., ‘Moving shoulders up and down’, ‘Circling shoulders forward and backward’) (‘Shoulder’), (2) exercises to optimize and maintain swallowing function (e.g., ‘Swallowing with strength: effortful swallow’, ‘Taking sips of water regularly’ (‘Swallow’), (3) exercises to optimize and maintain vocal health and vocal function (e.g., ‘Humming with gradually increased volume, and with exaggerated jaw movement’, ‘Slide up the pitch scale as high as possible’ (Falsetto exercise) (‘Voice’), and (4) exercises to optimize and maintain speech function and functional communication (e.g., ‘Articulate each syllable’, ‘Stretching the tongue out straight’(‘Speech’). HM informs the patient on possible swallowing, speech, and shoulder problems during treatment, and encourages patients to perform exercises to maintain function [17]. Based on our clinical experience and earlier study [17], we encourage patients to exercise at least once a day for 15 min and preferably three times a day. HM is available in two different formats: (a) online [36] with a description of the exercises, and with photo and video examples of the exercises, (b) a 28-page booklet, with the same information as the online version, photo examples of the exercises, and a 15-min instructional DVD with video examples of the exercises. Patients can choose the format that fits their needs best.

Before patients carry out HM at home, a 15-min face-to-face instruction session with expert speech and swallowing therapist’s demonstration of the exercises is planned on the first day of (C)SW-IMRT. During the course, each patient is contacted by phone in a weekly 10-min coaching session by an experienced speech therapist. Patients are asked to fill out a diary on paper or online for 12 weeks. In their diaries, patients note which exercises (of the four exercise categories) they performed, and the frequency of exercising (1, 2, or 3 times per day).

Measures

A study specific survey was composed comprising items on sociodemographic data (age, gender, HM format, and number of coaching sessions) and on HNC-specific HRQOL (EORTC-QLQ-H&N35) [37]. This survey was assessed at baseline (T0), every week from the 1st till the 6th week of treatment with (C)SW-IMRT (T1-T6), and 6 weeks after the end of treatment (T12). Clinical data (tumour site, tumour stage, and treatment modality) were abstracted from the hospital information system.

Adherence and exercise performance levels

Adherence concerned the percentage of patients who started and kept up with the HM exercise program at least once a day across the 6-week period during treatment with (C)SW-IMRT and across the 12-week period during and after treatment with (C)SW-IMRT. Adherence was assessed using patient-completed diaries. Non-adherence was defined as failure to perform any of the exercises. To gain insight into which exercises were performed most often, patient’s diaries were analyzed in more detail regarding the frequency of exercising, exercise performance levels per week during 6 weeks while undergoing treatment, and during 12 weeks during and after treatment. Exercise performance was based on patient diaries and consisted of low-, moderate-, and high-performance levels during 6 and 12 weeks, respectively: (1) low, indicating an exercise performance of all exercise categories at most once a day on average (range 1–168; range 1–336), (2) moderate, indicating an exercise performance of all categories between once and twice a day on average (range 169–336; range 337–672), and (3) high, indicating an exercise performance of all exercise categories at least twice a day on average (range 337–504; range 673–1008). To gain insight into which exercise category was performed most often, the diaries were analyzed in detail regarding the exercise frequency per day on average (1–3 times), the exercise frequency per week (the total number of exercise performed per week ranged from 0 to 84 (4 exercise categories 3 times per day for 7 days), and type of exercise (‘Shoulder’, ‘Swallow’, ‘Voice’, and ‘Speech’).

Factors associated with exercise performance level

Data were collected on gender, age, tumour site (oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx), tumour stage (I, II, III, IV), treatment modality (SW-IMRT or CSW-IMRT), intervention format (online or booklet), coaching (number of sessions), and on HNC-specific HRQOL (EORTC-QLQ-H&N35).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize adherence, exercise performance levels, number of coaching sessions, demographic and clinical characteristics, and HNC-specific HRQOL (EORTC-QLQ-H&N35). A Chi-square test was used to examine differences in exercise performance level at 6 and 12 weeks (low vs moderate/high), regarding gender (male vs female), tumour site (oral cavity/oropharynx vs hypopharynx/larynx), tumour stage (stage I/II vs stage III/IV), treatment modality (RT vs CRT), and intervention format (online vs booklet). Fisher’s exact tests were used when the assumption of the expected value of each cell of 5 or higher was not met. Independent samples t tests were used to investigate differences in exercise performance level at 6 and 12 weeks (low vs moderate/high) regarding age, and Mann–Whitney U tests regarding the number of coaching sessions (at 6 or 12 weeks), and HNC-specific HRQOL at baseline (EORTC-QLQ-H&N35). Longitudinal analysis was performed by generalized estimating equations (GEEs) (jointly testing the bivariate effect of variables and its time dependence) with a logit link function and autoregressive correlation matrix of the first order [AR(1)]. Longitudinal changes in exercise performance level (low vs moderate/high) per week in relation to each of the symptom subscales of the EORTC-QLQ-H&N35 were analyzed. HNC-specific HRQOL was measured weekly from baseline through week 6, and at the end of week 12. The model included both the current value of the symptom subscales as well as the lagged value (i.e. the value of the symptom subscale at the previous assessment) of the symptom subscale. Confounding factors (e.g., number of coaching sessions) were added as fixed effects in the model. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22. For all analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

Ninety-seven patients were eligible during the study period. Thirty-seven patients did not participate (38%). Of these 37 patients, 19 were not willing to participate, 12 refused to fill out any questionnaires, and 6 declared to be too tired. Of 60 patients who performed the exercises, 10 diaries were not available, leaving a study sample of 50 patients. Table 1 shows the demographic, tumour, and treatment characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics (n = 50)

| Age | |

| Mean age, years (range) | 61 (40–77) |

| N (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 39 (78) |

| Female | 11 (22) |

| Tumour site | |

| Oropharynx | 30 (60) |

| Larynx | 15 (30) |

| Hypopharynx | 5 (10) |

| Tumour stage | |

| I | 4 (8) |

| II | 3 (6) |

| III | 17 (34) |

| IV | 26 (52) |

| Treatment | |

| SW-IMRT | 23 (46) |

| CSW-IMRT | 27 (54) |

| HM format | |

| Online | 26 (52) |

| Booklet | 24 (48) |

| 12-week coaching sessions | |

| Median (range) | 9 (4–12) |

Adherence

Table 2 shows that of 50 patients, 35 patients started and kept up exercising across the first 6 weeks (6-week adherence rate of 70% and 19 patients kept up exercising up to 12 weeks (12-week adherence rate of 38%).

Table 2.

Participant’s weekly and 12-week exercise performance levels (n = 50)

| Patient number | Format | Week number | Total number of exercises performed | 12-week exercise performance level | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Low (1–336) | |||

| 73 | ONLINE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 9 | ONLINE | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| 74 | ONLINE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |

| 106 | BOOK | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |

| 76 | BOOK | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | |

| 132 | ONLINE | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | |

| 44 | BOOK | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 73 | |

| 69 | BOOK | 12 | 23 | 24 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 | |

| 154 | ONLINE | 16 | 14 | 25 | 21 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 89 | |

| 150 | ONLINE | 0 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 16 | 4 | 0 | 96 | |

| 40 | ONLINE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 21 | 3 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 112 | |

| 183 | BOOK | 34 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 115 | |

| 155 | BOOK | 12 | 12 | 6 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 132 | |

| 109 | ONLINE | 44 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 56 | 152 | |

| 96 | BOOK | 3 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 32 | 31 | 4 | 17 | 20 | 15 | 18 | 19 | 177 | |

| 151 | BOOK | 8 | 28 | 16 | 17 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 14 | 194 | |

| 80 | BOOK | 28 | 36 | 40 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 16 | 24 | 12 | 20 | 16 | 220 | |

| 38 | ONLINE | 24 | 40 | 48 | 44 | 48 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 268 | |

| 149 | BOOK | 40 | 47 | 28 | 48 | 36 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 271 | |

| 137 | BOOK | 16 | 28 | 29 | 25 | 26 | 30 | 17 | 34 | 30 | 28 | 23 | 0 | 286 | |

| 95 | BOOK | 18 | 24 | 26 | 18 | 28 | 19 | 24 | 24 | 28 | 24 | 25 | 28 | 286 | |

| 78 | BOOK | 29 | 39 | 36 | 32 | 28 | 32 | 25 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 28 | 28 | 292 | |

| 55 | ONLINE | 12 | 63 | 48 | 51 | 20 | 20 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 16 | 28 | 28 | 310 | |

| 130 | ONLINE | 34 | 34 | 49 | 41 | 34 | 15 | 30 | 49 | 15 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 313 | |

| 45 | BOOK | 48 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 24 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 316 | |

| 37 | BOOK | 36 | 84 | 84 | 36 | 24 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 320 | |

| 110 | ONLINE | 24 | 28 | 28 | 16 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 320 | |

| 107 | ONLINE | 32 | 12 | 32 | 50 | 28 | 25 | 33 | 43 | 25 | 27 | 23 | 20 | 350 | Moderate (337–672) |

| 71 | ONLINE | 21 | 72 | 61 | 64 | 47 | 50 | 44 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 386 | |

| 97 | ONLINE | 48 | 56 | 52 | 40 | 36 | 36 | 32 | 8 | 0 | 36 | 32 | 28 | 404 | |

| 75 | BOOK | 36 | 84 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 440 | |

| 57 | ONLINE | 28 | 56 | 52 | 58 | 52 | 40 | 28 | 28 | 36 | 20 | 28 | 24 | 450 | |

| 170 | BOOK | 72 | 84 | 84 | 72 | 72 | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 453 | |

| 134 | BOOK | 57 | 63 | 67 | 60 | 60 | 66 | 47 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 464 | |

| 39 | BOOK | 0 | 0 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 40 | 56 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 480 | |

| 94 | ONLINE | 44 | 68 | 54 | 46 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 30 | 36 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 542 | |

| 118 | ONLINE | 64 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 69 | 63 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 548 | |

| 22 | BOOK | 48 | 70 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 550 | |

| 14 | ONLINE | 39 | 55 | 66 | 56 | 59 | 46 | 17 | 25 | 42 | 50 | 53 | 49 | 557 | |

| 186 | ONLINE | 63 | 66 | 60 | 48 | 60 | 54 | 55 | 53 | 46 | 46 | 9 | 0 | 560 | |

| 187 | BOOK | 72 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 76 | 67 | 52 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 611 | |

| 93 | ONLINE | 0 | 64 | 80 | 84 | 80 | 68 | 53 | 28 | 36 | 36 | 64 | 80 | 673 | High (673–1008) |

| 168 | ONLINE | 0 | 28 | 36 | 84 | 84 | 81 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 691 | |

| 129 | ONLINE | 0 | 24 | 50 | 76 | 80 | 84 | 43 | 38 | 84 | 80 | 84 | 84 | 727 | |

| 20 | BOOK | 48 | 84 | 42 | 42 | 84 | 72 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 876 | |

| 182 | ONLINE | 52 | 80 | 84 | 84 | 66 | 60 | 64 | 75 | 79 | 80 | 76 | 84 | 884 | |

| 133 | ONLINE | 64 | 84 | 80 | 80 | 72 | 84 | 60 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 64 | 44 | 884 | |

| 72 | BOOK | 72 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 75 | 75 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 978 | |

| 167 | BOOK | 60 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 984 | |

| 70 | ONLINE | 72 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 80 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 992 | |

0 = non-active (does not perform any exercises)

84 = high performance (i.e., four exercise categories three times per day for 7 days)

Exercise performance level

Table 2 presents the 12-week exercise performance levels, and exercise performance levels per week of all 50 individual patients.

Of all 50 patients, 20 patients (40%) had a low 6-week exercise performance level, 17 (34%) had a moderate, and 13 (26%) had a high exercise performance level.

Of all 50 patients, 27 patients (54%) had a low 12-week exercise performance level, 14 (28%) had a moderate, and 9 (18%) had a high exercise performance level).

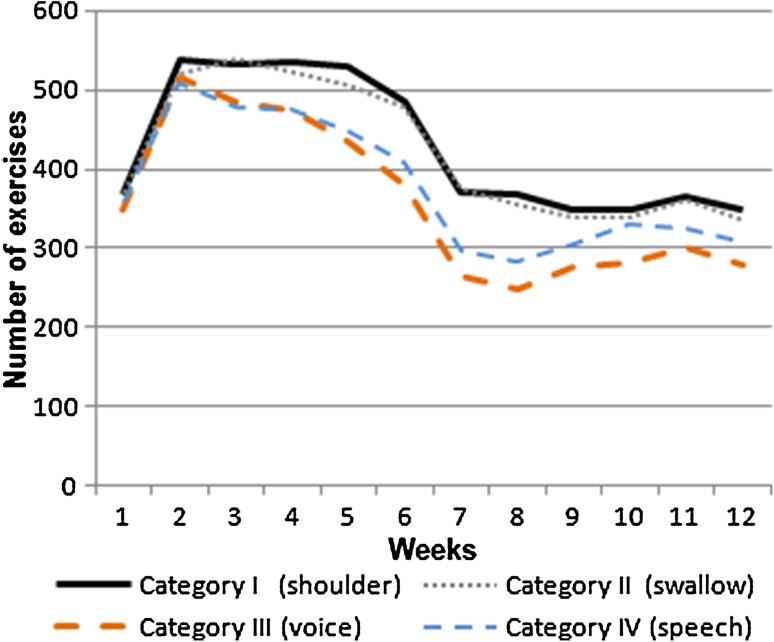

Figure 1 presents the weekly exercise performance by exercise category. At the 6th and the 12th week, respectively, patients most often (484 and 348 times) performed the exercises to maintain mobility of the head, neck, and shoulders, and the exercises and strategies to optimize, and to maintain swallowing function: 477 and 336 times.

Fig. 1.

Total number of weekly performed exercises by category (n = 50)

Factors related to exercise performance levels

Table 3 shows the 6- and 12-week exercise performance levels in relation to demographic (age, gender) and clinical factors (tumour site, tumour stage, and treatment modality), HM intervention format, and to the median number of coaching sessions. Significantly, more patients treated with chemotherapy (CSW-IMRT) had a low exercise performance level over the first 6 weeks compared with patients who were treated with SW-IMRT alone, χ 2(1, N = 50) = 5.92, p = 0.15 as well as over the entire 12 weeks, χ 2(1, N = 50) = 13.36, p < 0.001. Exercise performance levels during 6 and 12 weeks were not significantly associated with age, gender, tumour site, tumour stage, HM intervention format, or number of coaching sessions. HNC-specific HRQOL at baseline was not associated with exercise performance level during or after treatment (Table 4). Changes in exercise performance levels per week in relation to the value of the EORTC-QLQ-H&N35 subscales in the previous week were analyzed, using generalized estimating equations (GEEs). Exercise performance level was significantly related to the symptom item ‘Problems with mouth opening’: experiencing more problems with mouth opening in the previous week yielded lower odds for a moderate-to-high exercise performance level in the next week [OR (95% CI) = 0.91 (0.84–0.99), p = 0.037 (Table 5)]. This means that the more problems a patient experiences with opening his mouth in the previous week, the more likely it is he will have a lower exercise performance level the next week. However, after correcting for treatment modality (SW-IMRT vs CSW-IMRT), this significant effect of problems with mouth opening disappeared (p = 0.16).

Table 3.

Exercise performance levels in relation to demographic and clinical factors

| Low level after 6 weeks | Moderate-to-high level after 6 weeks | p value | Low level after 12 weeks | Moderate-to-high level after 12 weeks | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| 20 (40) | 30 (60) | 27 (54) | 23 (46) | |||

| Age | 0.48 | 0.12 | ||||

| Mean age, years (range) | 60 (46–76) | 62 (40–77) | 59 (40–76) | 63 (50–77) | ||

| Gender | 0.74 | 0.97 | ||||

| Male | 15 (38) | 24 (62) | 21 (54) | 18 (46) | ||

| Female | 5 (45) | 6 (55) | 6 (54) | 5 (46) | ||

| Tumour site | 0.56 | 0.64 | ||||

| Oropharynx | 13 (43) | 17 (57) | 17 (57) | 13 (43) | ||

| Larynx/Hypopharynx | 7 (35) | 13 (65) | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | ||

| Tumour stage | 1.00 | 0.69 | ||||

| I/II | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | ||

| III/IV | 17 (40) | 26 (60) | 24 (56) | 19 (44) | ||

| Treatment | 0.015 | <0.001 | ||||

| SW-IMRT | 5 (22) | 18 (78) | 6 (26) | 17 (74) | ||

| CSW-IMRT | 15 (56) | 12 (44) | 21 (78) | 6 (22) | ||

| HM format | 0.42 | 0.25 | ||||

| Online | 9 (35) | 17 (65) | 12 (46) | 14 (54) | ||

| Booklet | 11 (46) | 13 (54) | 15 (63) | 9 (37) | ||

| Coaching sessions | 0.18 | 0.63 | ||||

| Median (range) | 5 (3–6) | 4 (2–6) | 9 (4–12) | 9 (4–12) |

Table 4.

Exercise performance levels in relation to HNC-specific HRQOL at baseline

| EORTC-QLQ-H&N35 | Low level after 6 weeks | Moderate-to-high level after 6 weeks | p value | Low level after 12 weeks | Moderate-to-high level after 12 weeks | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 20 (40%) | N = 30 (60%) | N = 27 (54%) | N = 23 (46%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||||

| Oral pain | 26.2 (22.0) | 30.3 (28.5) | 0.83 | 27.5 (26.2) | 30.1 (26.1) | 0.61 |

| Swallowing problems | 17.5 (22.1) | 20.8 (24.2) | 0.52 | 19.4 (24.8) | 19.6 (21.8) | 0.70 |

| Sense problems | 7.5 (16.6) | 3.9 (12.9) | 0.18 | 7.4 (16.8) | 2.9 (10.8) | 0.20 |

| Speech problems | 16.7 (23.8) | 22.6 (26.8) | 0.31 | 16.9 (22.7) | 24.1 (28.5) | 0.27 |

| Social eating problems | 10.0 (12.8) | 14.2 (21.6) | 0.83 | 13.9 (21.2) | 10.9 (15.2) | 0.75 |

| Social contact problems | 7.3 (10.8) | 9.8 (17.6) | 0.95 | 8.4 (14.1) | 9.3 (16.5) | 0.81 |

| Teeth problems | 11.7 (22.4) | 22.2 (35.4) | 0.38 | 16.0 (28.3) | 20.3 (34.4) | 0.81 |

| Mouth opening problems | 5.0 (12.2) | 14.4 (31.2) | 0.51 | 9.9 (24.1) | 11.6 (27.7) | 0.99 |

| Dry mouth | 10.0 (15.7) | 11.1 (22.0) | 0.86 | 11.1 (22.6) | 10.1 (15.7) | 0.79 |

| Sticky saliva | 20.0 (25.1) | 12.2 (23.9) | 0.18 | 21.0 (29.4) | 8.7 (15.0) | 0.16 |

| Coughing | 20.0 (19.9) | 18.9 (20.9) | 0.80 | 19.7 (19.1) | 18.8 (22.1) | 0.75 |

| Feeling ill | 11.7 (16.3) | 16.7 (24.4) | 0.61 | 13.6 (19.1) | 15.9 (24.3) | 0.86 |

Table 5.

Course of HNC-specific HRQOL in relation to weekly exercise performance level

| EORTC-QLQ-H&N35 | Current value | Lagged value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Oral pain | 1.03 | 0.94–1.12 | 0.57 | 0.93 | 0.81–1.06 | 0.26 |

| Swallowing problems | 1.07 | 0.97–1.19 | 0.19 | 0.90 | 0.80–1.01 | 0.063 |

| Sense problems | 1.04 | 0.92–1.18 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 0.83–1.06 | 0.31 |

| Speech problems | 0.95 | 0.85–1.07 | 0.41 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.04 | 0.22 |

| Social eating problems | 1.09 | 0.95–1.24 | 0.22 | 0.85 | 0.71–1.01 | 0.058 |

| Social contact problems | 0.81 | 0.65–1.02 | 0.068 | 1.04 | 0.89–1.21 | 0.65 |

| Teeth problems | 1.04 | 0.92–1.17 | 0.55 | 0.95 | 0.86–1.06 | 0.39 |

| Mouth opening problems | 0.95 | 0.82–1.09 | 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.84–0.99 | 0.037* |

| After correcting for treatment | 0.96 | 0.81–1.13 | 0.59 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.03 | 0.16 |

| Dry mouth | 0.97 | 0.85–1.11 | 0.70 | 0.93 | 0.83–1.03 | 0.16 |

| Sticky saliva | 0.96 | 0.87–1.07 | 0.46 | 0.92 | 0.81–1.04 | 0.16 |

| Coughing | 1.04 | 0.95–1.13 | 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.81–1.0 | 0.080 |

| Feeling ill | 0.97 | 0.87–1.07 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 0.91–1.11 | 0.99 |

OR odds ratio for moderate/high-performance level per increase of ten points on the subscale

* p < 0.05

Discussion

The key findings of this study are that in HNC patients treated with SW-IMRT alone or in combination with chemotherapy [(C)SW-IMRT] adherence to a guided home-based prophylactic exercise program was high in the first 6 weeks (70%), but dropped after completion of treatment. Exercise performance levels during and after treatment were low especially in patients who were treated with SW-IMRT in combination with chemotherapy.

Few studies have investigated exercise adherence rates among HNC patients during treatment. These studies have yielded inconsistent findings with adherence rates ranging from 13 to 71% [17, 21, 25, 31–33]. This variety of adherence percentages may be a matter of definition. In this study, we used a rather rigid definition of adherence. Adherence was viewed as a dichotomous outcome with a pre-specified threshold value. This means for instance that a patient who was adherent to the program for 6 weeks and took a break from exercise for a week but continued to exercise for the next 5 weeks was defined as non-adherent. Adherence can also be viewed as a categorical or as a continuous outcome (the total number of exercise performed or the percentage of exercises completed [38]). According to Huang [39], only percentage of actual exercise activity over an expected exercise activity, or the number of exercise sessions completed at the prescribed level divided by the total number of exercise sessions prescribed, reflects the essence of adherence. However, the specific timing and the necessary amount of prescribed prophylactic exercises to obtain any therapeutic benefit are largely unknown. In the literature, a gap exists for well-developed measures that capture self-reported adherence to prescribed but unsupervised home-based exercises [40].

Besides insight into adherence to an intervention, it is also interesting to have a closer look on how well patients perform. Our study showed that 40% had a low 6-week exercise performance, while more than half of participants had a low 12-week performance. In a study of Mortensen [32] evaluating the impact of home-based prophylactic swallowing exercises on swallowing-related outcomes in HNC patients treated with curative RT, more patients (53%) than in our study had low (5-week) exercise performance levels. In a retrospective study of Hutcheson [15], 45% of the adherent patients performed the prescribed prophylactic exercises more than four times per day. However, the results of these studies are difficult to compare because of the various categorisations of exercise performance level as outcome measure.

In our study, lower 6- and 12-week exercise performance levels were significantly associated with treatment modality (CSW-IMRT vs SW-IMRT). In addition, we found a progressively downward trend in prophylactic exercise performance, indicating that exercise performance levels were reduced as CSW-IMRT treatment advanced. The previous studies showed an increased symptom burden if chemotherapy was added as treatment modality [5]. HNC patients undergoing CRT experience several toxicities which may result in a reduction of the number of prophylactic exercises completed [41].

A limitation of this study was that the study sample probably consisted of motivated HNC patients who were committed to exercise and who were motivated to complete their exercise diaries also. However, we did not apply a motivational questionnaire, so firm conclusions on the impact of motivation to start exercising cannot yet be drawn. Study results may not be generalizable to a wider population of HNC patients who may feel less motivated. In addition, in this study, we chose to focus on (deterioration of) HNC-specific quality of life outcomes as possible barriers for exercise performance. To evaluate (other) factors possibly associated with exercise performance levels, larger studies should be conducted using objective functional outcome measures in addition to patient-reported outcomes [5, 7], and psychosocial factors [17]. Furthermore, daily exercise behaviour was self-reported by participants and, therefore, may be subject to bias. In an attempt to minimize bias, exercise logs were completed daily. It is not certain, however, that these instructions were followed. The strengths of this study lie in the use of 6- and 12-week adherence data, and data on levels of exercise performance. There is growing evidence of the potential benefits of prophylactic exercises among HNC patients undergoing (C)RT [21, 23–25, 31], but the factors associated with adherence to home-based exercises are largely unknown. Further research is needed to study predictors to improve adherence, such as the perception of illness, the perception of ability to complete therapy, patients’ motivation and intention, behaviours related to home-based exercises, and social support and guidance [42].

Conclusion

Adherence of HNC patients to a guided home-based prophylactic exercise program during (C)SW-IMRT was high during the 6 weeks of treatment, but dropped afterwards. Exercise performance levels were low especially in patients who were treated with chemotherapy in combination with SW-IMRT.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding) and Fonds NutsOhra.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

We have full control of all primary data, and we are ready to allow the journal to review data if requested. No competing financial interests exist for either author.

References

- 1.Van der Laan HP, Gawryszuk A, Christianen MEMC, et al. Swallowing-sparing intensity-modulated radiotherapy for HNC patients: treatment planning optimization and clinical introduction. Radiother Oncol. 2013;107:282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanchard P, Baujat B, Holostenco V, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): a comprehensive analysis by tumour site. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pignon JP, le Maître A, Maillard E, et al. MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taibi R, LLeshi A, Barzan L, et al. Head and neck cancer survivor patients and late effects related to oncologic treatment: update of literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:1473–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Fuller CD, et al. Patterns of symptom burden during radiation therapy or concurrent chemoradiation for head and neck cancer: a prospective analysis using the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory—Head and Neck Module. Cancer. 2014;120(13):1975–1984. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Buffart LM, Heymans MW, et al. The course of health-related quality of life in had and neck cancer patients treated with chemoradiation: a prospective cohort study. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cousins N, MacAulay F, Lang H, et al. A systematic review of interventions for eating and drinking problems following treatment for head and neck cancer suggest a need to look beyond swallowing and trismus. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(5):387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paleri V, Carding P, Chatterjee S, et al. Voice outcomes after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for advanced nonlaryngeal head and neck cancer: a prospective study. Head Neck. 2012;34(12):1747–1752. doi: 10.1002/hed.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russi EG, Corvò R, Merlotti A, et al. Swallowing dysfunction in head and neck cancer patients treated by radiotherapy: review and recommendations of the supportive task group of the Italian Association of Radiation Oncology. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(8):1033–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stubblefield MD. Radiation fibrosis syndrome: neuromuscular and musculoskeletal complications in cancer survivors. PMR. 2011;3(11):1041–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.08.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ, et al. Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): a phase 3 multicentre randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:127–136. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergeer MR, Doornaert PA, Rietveld DH, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy reduces radiation-induced morbidity and improves health-related quality of life: results of a nonrandomized prospective study using a standardized follow-up program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doornaert P, Verbakel WF, Rietveld DH, et al. Sparing the contralateral submandibular gland without compromising PTV coverage by using volumetric modulated arc therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:74. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Laan HP, Christianen MEMC, Bijl HP, et al. The potential benefit of swallowing sparing intensity modulated radiotherapy to reduce swallowing dysfunction: an in silico planning comparative study. Radiother Oncol. 2012;103:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutcheson KA, Bhayani MK, Beadle BM, et al. Eat and exercise during radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for pharyngeal cancers: use it or lose it. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(11):1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahlberg A, Engström T, Nikolaidis P, et al. Early self-care rehabilitation of head and neck cancer patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131(5):552–561. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.532157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cnossen IC, van Uden-Kraan CF, Rinkel RNPM, et al. Multimodal guided self-help exercise program to prevent speech, swallowing, and shoulder problems among head and neck cancer patients: a feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e74. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenthal DI, Lewin JS, Eisbruch A. Prevention and treatment of dysphagia and aspiration after chemoradiation for head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(17):2636–2643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wall LR, Ward EC, Cartmill B, et al. Physiological changes to the swallowing mechanism following (chemo)radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2013;28(4):481–493. doi: 10.1007/s00455-013-9491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter KU, Jolly S. Clinical review of physical activity and functional considerations in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1475–1479. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1736-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinn EH, Basen-Engquist K, Baum G, et al. Adherence to preventive exercises andself-reported swallowing outcomes in post-radiation head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 2013;35(12):1707–1712. doi: 10.1002/hed.23255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duarte VM, Chhetri DK, Liu YF, et al. Swallow preservation exercises during chemoradiation therapy maintains swallow function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(6):878–884. doi: 10.1177/0194599813502310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotz T, Federman AD, Kao J, et al. Prophylactic swallowing exercises in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiation: a randomized trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(4):376–382. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2012.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carnaby-Mann G, Crary MA, Schmalfuss I, et al. “Pharyngocise”: randomized controlled trial of preventative exercises to maintain muscle structure and swallowing function during head-and-neck chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(1):210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Molen L, van Rossum MA, Burkhead LM, et al. A randomized preventive rehabilitation trial in advanced head and neck cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy: feasibility, compliance, and short-term effects. Dysphagia. 2011;26(2):155–170. doi: 10.1007/s00455-010-9288-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carroll WR, Locher JL, Canon CL, et al. Pretreatment swallowing exercises improve swallow function after chemoradiation. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(1):39–43. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31815659b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulbersh BD, Rosenthal EL, McGrew BM, et al. Pretreatment, preoperative swallowing exercises may improve dysphagia quality of life. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(6):883–886. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000217278.96901.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lønbro S, Dalgas U, Primdahl H, et al. Lean body mass and muscle function in head and neck cancer patients and healthy individuals—results form the DAHANCA 25 study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:1543–1551. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.822553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roe JW, Ashforth KM. Prophylactic swallowing exercises for patients receiving radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;19(3):144–149. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283457616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paleri V, Roe JW, Strojan P, et al. Strategies to reduce long-term postchemoradiation dysphagia in patients with head and neck cancer: an evidence-based review. Head Neck. 2014;36(3):431–443. doi: 10.1002/hed.23251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng KA, Kuan EC, Unger L, et al. A swallow preservation protocol improves function for veterans receiving chemoradiation for head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(5):863–867. doi: 10.1177/0194599815575508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mortensen HR, Jensen K, Aksglaede K, et al. Prophylactic swallowing exercises in head and neck cancer radiotherapy. Dysphagia. 2015;30(3):304–314. doi: 10.1007/s00455-015-9600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen K, Eriksen EM, Behrens M et al (2015) Prophylactic swallowing exercises during and after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer—results of phase I trial (Poster). Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00332865

- 34.Who can take part in a clinical trial? Performance status (World Health Organization scale). http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/find-a-clinical-trial/how-to-join-a-clinical-trial/who-can-take-part-in-a-clinical-trial. Accessed July 2016

- 35.RTOG/EORTC Late Radiation Morbidity Scoring Schema. https://www.rtog.org/ResearchAssociates/AdverseEventReporting/RTOGEORTCLateRadiationMorbidityScoringSchema.aspx. Accessed July 2016

- 36.Head Matters. http://www.halszaken-vumc.nl. Accessed July 2016

- 37.EORTC Quality of life. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/. Accessed July 2016

- 38.Pinto BM, Rabin C, Dunsiger S. Home-based exercise among cancer survivors: adherence and its predictors. Psychooncology. 2009;18(4):369–376. doi: 10.1002/pon.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang HP, Wen FH, Tsai JC, et al. Adherence to prescribed exercise time and intensity declines as the exercise program proceeds: findings from women under treatment for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(7):2061–2071. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2567-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bollen JC, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, et al. A systematic review of measures of self-reported adherence to unsupervised home-based rehabilitation exercise programmes, and their psychometric properties. BMJ Open. 2016;4:e005044. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Virani A, Kunduk M, Fink DS, et al. Effects of 2 different swallowing exercise regimens during organ-preservation therapies for function. Head Neck. 2015;37(2):162–170. doi: 10.1002/hed.23570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Essery R, Geraghty AWA, Kirby S, et al. Predictors of adherence to home-based physical therapies: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2016 doi: 10.3109/09638288.2016.1153160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]