Abstract

Background:

Cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) is an autosomal dominant disease that affects the skeletal system. Common symptoms of CCD include hypoplasia or aplasia of the clavicles, delayed or even absent closure of the fontanels, midface hypoplasia, short stature, and delayed eruption of permanent and supernumerary teeth. Previous studies reported a connection between CCD and the haploinsufficiency of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2). Here, we report a sporadic Chinese case presenting typical symptoms of CCD.

Methods:

We made genetic testing on this sporadic Chinese case and identified a novel RUNX2 frameshift mutation: c.1111dupT. In situ immunofluorescence microscopy and osteocalcin promoter luciferase assay were performed to compare the functions of the RUNX2 mutation with those of wild-type RUNX2.

Results:

RUNX2 mutation was observed in the perinuclear region, cytoplasm, and nuclei. In contrast, wild-type RUNX2 was confined in the nuclei, which indicated that the subcellular compartmentalization of RUNX2 mutation was partially perturbed. The transactivation function on osteocalcin promoter of the RUNX2 mutation was obviously abrogated.

Conclusions:

We identified a sporadic CCD patient carrying a novel insertion/frameshift mutation of RUNX2. This finding expanded our understanding of CCD-related phenotypes.

Keywords: Cleidocranial Dysplasia, Frameshift Mutation, Runt-related Transcription Factor 2

Introduction

Cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD; OMIM 119600) is an autosomal dominant disease that affects the skeletal system. Common symptoms of CCD include hypoplasia or aplasia of the clavicles, delayed or even absent closure of fontanels, midface hypoplasia, short stature, delayed eruption or impaction of permanent and supernumerary teeth, as well as other skeletal malformations, such as wide pubic symphysis, brachycephalic skull, and abnormal mandibular ramus and coronoid process.[1,2] Among the various phenotypic spectra of CCD, hypoplasia or aplasia of the clavicles and dental abnormalities are common. Panoramic radiography is crucial for diagnosing CCD.[3] The prevalence of CCD is about one in millions of live births in any gender or race.[4,5]

Previous studies reported a connection between CCD and the haploinsufficiency of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2).[6,7,8,9] RUNX2 controls normal bone formation by regulating the differentiation of mesenchymal precursor cells to osteoblasts and the growth and maturation of osteoblasts. RUNX2-deficient mice lack osteoblasts and fail to form bones.[10] The RUNX2 gene has been mapped to chromosome 6p21 and consists of several established functional domains. The Runt domain, an evolutionary conserved polypeptide motif located in the N-terminal of RUNX2, mediates DNA binding and protein–protein interaction, including heterodimerization with the core-binding factor subunit beta.[11] Adjacent to the Runt domain is the nuclear localization signal, which accumulates RUNX2 in the cell nucleus.[12,13] Furthermore, RUNX2 possesses a Q/A domain with glutamine and alanine repeats,[14] and the C-terminus consists of a transactivation proline-serine-threonine-rich (PST) domain with abundant PST.[7] The nuclear matrix-targeting signal (NMTS) is necessary for subnuclear localization and protein binding in the middle of the PST domain.[15,16] The Val-Trp-Arg-Pro-Tyr (VWRPY) peptide that supports transcriptional repression comprises the last section of the C-terminal.

RUNX2 mutation is not observed in approximately 30% of CCD patients.[12] Previous studies have identified over eighty heterozygous RUNX2 mutations in CCD patients.[4,13,17,18] RUNX2 mutations are generally located in the Runt domain, most of which are missense mutations. Only 10% of the C-terminal mutations are missense mutations.[18,19] In the present study, we identified a novel RUNX2 mutation: c.1111dupT (p.Ser371PhefsX14), in a sporadic case.

Methods

Patient selection

A Chinese individual who presented with clinical symptoms of CCD was recruited. The Ethical Committee of Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology (PKUSSIRB-201627028) approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Genetic testing

Up to 3 ml of peripheral blood was drawn from the CCD-affected patient and stored in an anticoagulation tube containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Genomic DNA extraction from the whole blood of the patient was conducted with QIAamp® DNA Blood Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Exons 1–8 of the RUNX2 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using previous combinations of primers.[13] PCR amplifications were performed in a thermal cycler (PE 2400, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA) with 50 μl reaction volumes. Sequencing was performed at Life Technologies, Inc., Shanghai, China.

Plasmid DNA and mutagenesis

Plasmid vector coding-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP): pEGFP-C1-vector and pEGFP-C1-RUNX2 plasmids were purchased from Youbio (Changsha, China). pEGFP-C1-RUNX2 plasmid was PCR amplified using human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cDNA as the template and then cloned into the pEGFP-C1-vector between KpnI/SacII sites. The primers are 5’-ACTCTCGAGATGGCATCAAACAGCCTCTT-3’ (forward) and 5’-ACTCCGCGGTCAATAT GGTCGCCAAACAG-3’ (reverse). The amino acid duplication of RUNX2 mutation was accomplished by PCR amplification using pEGFP-C1-RUNX2 circular plasmid as the template, 5’-AACTGGGCCCTTTTTTCAGACCCCAGG-3’ as the forward primer, and 5’-CCTGGGGTCTGAAAAAAGGGCCCAGTT-3’ as the reverse primer. The construct was completely sequenced and used as the template in other cloning designs.

Cell culture

HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (HyClone, Logan, USA) supplemented with 100 mg/ml streptomycin and penicillin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), and then incubated in 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Western blotting analysis

HEK293T cells were seeded and transiently transfected with pEGFP-C1-vector, pEGFP-C1-RUNX2, and pEGFP-C1-RUNX2-mut, using Vigo Transfection Reagent.

Cells were lysed in Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), NaCl, and EDTA (TNE) buffer plus protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland) at 4°C for 30 min. These supernatants were resolved through SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis after centrifugation. The anti-GFP antibody was used (Santa Cruz, Dallas, USA).

In situ immunofluorescence microscopy

pEGFP-C1-RUNX2 and pEGFP-C1-RUNX2-mut plasmids were separately transfected into HEK293T cells and then cultured for 24 h. Afterward, the cells were processed and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 0.1% triton X-100 for 5 min each. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed three times with PBS, and then incubated with Goat Anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 for 1 h at room temperature. Prolong® Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) was used to mount the cover slides following three times washing with PBS. A Zeiss LSM710 (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to capture immunofluorescent signals.

Transient transfection and osteocalcin promoter luciferase assay

HEK293T cells were seeded in 24-well plates one day before transfection. Cells at 60%–80% confluence were transfected in 50 μl of Vigo Transfection Reagent. The pRenilla-TK vector was used as an internal control. After 48 h of transfection, the cells were collected and measured using the luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 20.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Results were examined by Student's t-test. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical findings

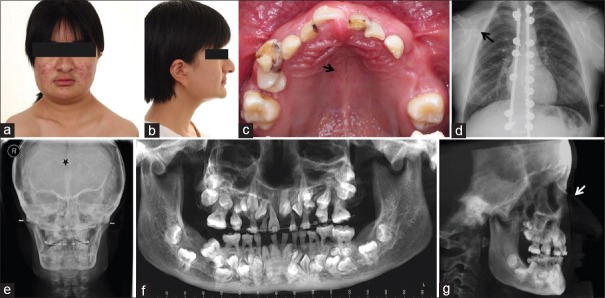

An 18-year-old female came to the hospital with a chief complaint of multiple impacted teeth. The patient showed typical clinical symptoms of CCD, including a concave profile and short stature (141 cm high). However, no abnormal hypermobility of the shoulders was found [Figure 1a and 1b]. The patient did not have any family history of this disease.

Figure 1.

Typical clinical and radiological findings in the CCD patient. (a) Shoulder mobility test revealed that the patient's shoulders cannot be brought closer. (b) Lateral photograph of the patient showed hypoplasia of the maxilla and a concave profile. (c) Oral manifestation revealed retention of deciduous teeth and a high-arched palate with a median pseudocleft. (d) Chest PA revealed thick and short clavicles with a bell-shaped thoracic cage. (e) Anteroposterior cephalogram revealed a Wormian bone (★) at the lambdoidal sutures, aplasia of the frontal sinus, and dysplasia of the zygomatic bone. (f) Panoramic radiography developed from CBCT confirmed retention of deciduous teeth, multiple permanent teeth impaction and supernumerary teeth as well as the parallel-sided borders of the ascending ramus. (g) Lateral cephalogram developed from CBCT showed hypoplasia of the maxilla and nasal bridge. CBCT: Cone beam computed tomography; PA: Posterioanterior; CCD: Cleidocranial dysplasia.

Oral manifestations and radiographic features

Oral manifestations include an edge-to-edge occlusion of the anterior teeth, retention of deciduous teeth, and a high-arched palate with a median pseudocleft [Figure 1c]. The 18-year-old patient had merely five permanent teeth (16, 14, 11, 26, and 36) erupted on her first visit.

Chest posterioanterior view revealed a bell-shaped thoracic cage and short and thick clavicles [Figure 1d]. Anteroposterior radiography revealed a plastic frontal sinus, Wormian bone, and dysplastic zygomatic bone [Figure 1e]. These symptoms were also previously observed in a CCD patient with T420I mutation in the PST domain.[20] The lateral cephalogram developed from cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) showed maxillary hypoplasia [Figure 1g]. The panoramic radiography developed from CBCT confirmed deciduous teeth retention, permanent teeth impaction, and delayed development with abnormal roots and multiple supernumerary teeth. It also revealed the parallel-sided anterioposterior borders of the ascending ramus, slender and pointed coronoid process facing upward, thin zygomatic arch and increased bone density between the anterior border of the ascending ramus and the inferior dental canal [Figure 1f]. The symptoms are consistent with those in the previous study.[3]

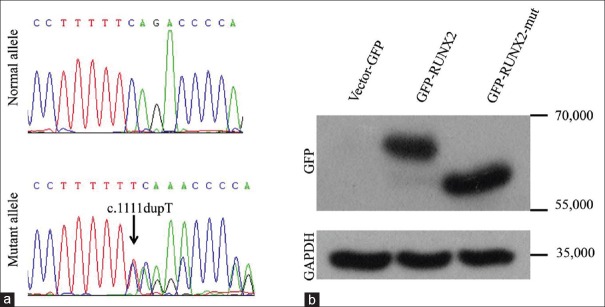

Mutation analysis

A novel single-base pair duplication: c.1111dupT in exon 8 was detected in the patient [Figure 2a], causing a frameshift mutation ending at the consequent premature stop codon 384, which led to a truncated RUNX2 protein comprising merely 383 amino acids. The result was confirmed by Western blot analysis [Figure 2b]. The NMTS region was involved in this mutation.

Figure 2.

Genetic sequencing and Western blot of wild-type RUNX2 and RUNX2 mutation. (a) Sequencing results showed the heterozygous duplicate mutant allele T. (b) Western blot confirmed the mutation that had 138 amino acids less than the wild type. GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFP: Green fluorescent protein; RUNX2: Runt-related transcription factor 2.

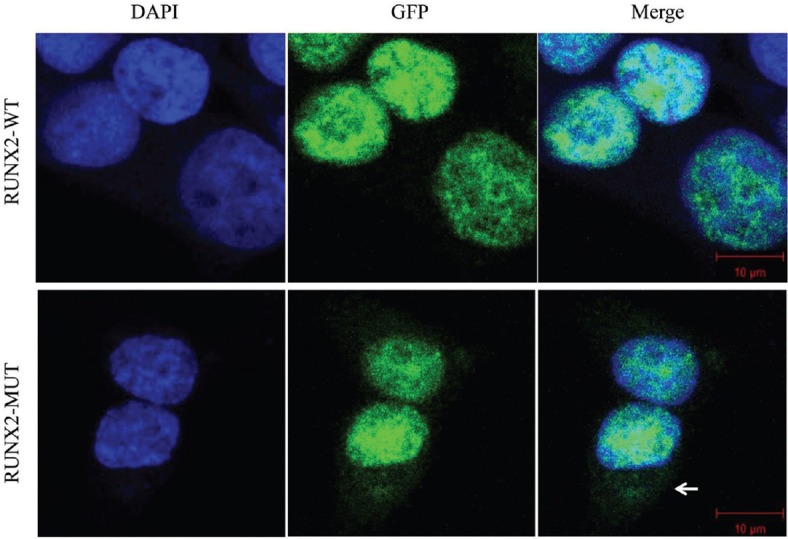

Nuclear localization of runt-related transcription factor 2 mutation

RUNX2 is localized in the cell nucleus and perinucleolar region.[14,21,22] The NMTS-associated subnuclear foci of RUNX2 are responsible for the transactivation of the osteoblast-specific osteocalcin gene in osseous cells.[14] To identify the nuclear localization of the RUNX2 mutation, we transfected both pEGFP-C1-RUNX2 and pEGFP-C1-RUNX2-mut plasmids into HEK293T cells. The subcellular localization of the wild-type RUNX2 and the mutation was observed by in situ immunofluorescence microscopy.

The RUNX2 mutation and wild-type RUNX2 accumulated in the nuclei of HEK293T cells [Figure 3]. However, the RUNX2 mutation was also observed in the perinuclear region and cytoplasm, which indicated that the subcellular compartmentalization of the RUNX2 mutation was partially perturbed.

Figure 3.

Nuclear localization of RUNX2 mutation. Wild-type RUNX2 was localized in the nuclei of HEK-293T cells, whereas RUNX2 mutation was observed in the nuclei and perinuclear region (←) and cytoplasm. DAPI: 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GFP: Green fluorescent protein; WT: Wild-type RUNX2; MUT: RUNX2 mutation; HEK: Human embryonic kidney; RUNX2: Runt-related transcription factor 2.

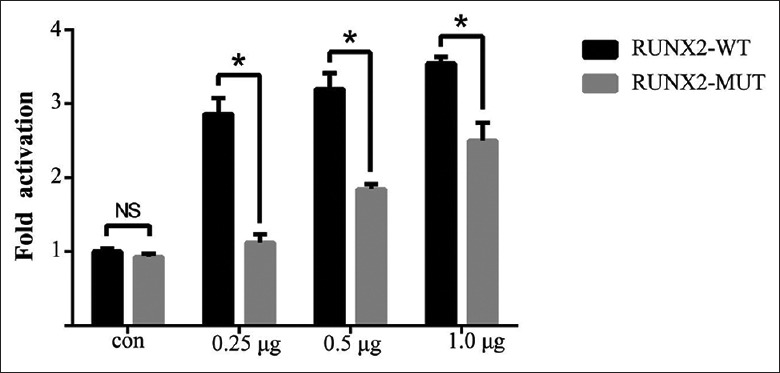

Transcription activation's abilities

To examine the effect of the RUNX2 proteins on the transactivation activity of HEK293T cells, we conducted DNA co-transfection experiments in HEK293T cells with the RUNX2-responsive osteocalcin promoter (p6OSE2-luc) as the reporter. Wild-type RUNX2 increased the promoter activity in transient transfection assays, whereas the transactivation function of the RUNX2 mutation was abrogated [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Transcription activation abilities. Transcriptional effects of the wild-type and mutant RUNX2 on osteocalcin promoter in HEK-293T cells. Luciferase activities were measured, and the value (ratio between firefly and Renilla luciferase) was obtained from the control group (empty vector) as one fold. Values are mean ± SD of independent experiments performed in triplicate. Results were examined by Student's t-test. t-value is 12.349, 10.334, and 7.017 separately for each quantity of transfection plasmids. *P < 0.05 versus WT. HEK: Human embryonic kidney; WT: Wild-type RUNX2; MUT: RUNX2 mutation; CON: Empty control; NS: Nonsignificant difference; SD: Standard deviation; RUNX2: Runt-related transcription factor 2.

Discussion

In the current study, we confirmed a novel RUNX2 mutation in a sporadic Chinese patient with symptoms of CCD. The mutation leading to a frameshift from codon 371 to the premature stop codon 384 is responsible for the haploinsufficiency of RUNX2, and therefore causes the disease. The RUNX2 mutation resulted in the absence of the NMTS domain and C-terminal pentapeptide VWRPY. The NMTS near the C-terminal of RUNX2 comprises 38 amino acids (from amino acid 397 to 434), forming a helix-loop-helix structure.[23] According to a previous study, the NMTS domain is responsible for RUNX2 retention in nuclear matrix-associated foci and important for the optimal activation of the bone-specific osteocalcin gene.[14] Interactions with SMADs, histone deacetylase 6, and Yes-associated protein might play a role in the mechanisms of the NMTS-mediating protein subnuclear distribution.[24,25] VWRPY interacts with a Groucho/TLE/R-esp repressor protein, and osteocalcin promoter is activated through a VWRPY-dependent mechanism.[21,26] The VWRPY domain is not important for the retention of RUNX2 in nuclear matrix-associated foci.[14] In the present study, the nuclear import of the RUNX2 mutant was partially abrogated, which does not coincide with the conclusion of Zaidi et al.[14] The perinuclear leak of RUNX2 mutant expression might explain its decreased ability in activating downstream genes as shown in the results of the luciferase assay. The decreased ability could be partly modified by increasing the dose of the RUNX2 mutant plasmid, implying a correlation between the dosage and the abrogated function of the RUNX2 mutant.

CCD has a wide spectrum of clinical symptoms. According to the OMIM, CCD is related to over 48 phenotypic features. Previous studies were performed to explain the genotype–phenotype correlation, but their results were controversial.[27,28,29,30,31] A wide variation of phenotype expressivity even within a family with identical RUNX2 mutation was observed.[28,31] A relationship between the stature and number of supernumerary teeth was observed.[12,31] Cunningham et al.[19] suggested that the C-terminal mutations of RUNX2 lead to a more severe phenotype because of the negative effects caused by the preservation of the Runt domain. In contrast, Bufalino et al.[29] implied a correlation between the region affected by mutations involving the Runt domain and the severity of dental phenotypes. Although the mutation was outside the Runt domain, the patient presented with severe dental abnormalities. Previous cases[32,33] revealed frameshift mutations in similar regions: c.1116_1119insC and c.1119delC. Both mutations demonstrated extremely similar craniofacial and dental phenotypes, including retained deciduous teeth, eruption failure of permanent dentition with abnormal roots, and multiple supernumerary teeth. However, more severe clavicle problems and spina bifida occulta were observed in the previous cases than in the present case. The difference might be attributed to environmental factors and epigenetic regulation including histone modifications and DNA methylation and copy number variation.

In summary, we identified a sporadic CCD patient carrying a novel insertion/frameshift mutation of RUNX2. This finding expanded our understanding of CCD-related phenotypes. Future studies of RUNX2 mutations may provide further insights into the phenotype-genotype correlation.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81200762).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Ning-Ning Wang

References

- 1.Shibata A, Machida J, Yamaguchi S, Kimura M, Tatematsu T, Miyachi H, et al. Characterisation of novel RUNX2 mutation with alanine tract expansion from Japanese cleidocranial dysplasia patient. Mutagenesis. 2016;31:61–7. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gev057. doi:10.1093/mutage/gev057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HJ, Nam SH, Kim HJ, Park HS, Ryoo HM, Kim SY, et al. Four novel RUNX2 mutations including a splice donor site result in the cleidocranial dysplasia phenotype. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:114–22. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20552. doi:10.1002/jcp.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNamara CM, O'Riordan BC, Blake M, Sandy JR. Cleidocranial dysplasia: Radiological appearances on dental panoramic radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1999;28:89–97. doi: 10.1038/sj/dmfr/4600417. doi:10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu LZ, Su WQ, Liu YF, Ge X, Zhang Y, Wang XJ. Role of the RUNX2 p.R225Q mutation in cleidocranial dysplasia: A rare presentation and an analysis of the RUNX2 protein structure. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:1187–94. doi: 10.4238/2014.February.27.3. doi:10.4238/2014.February.27.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mundlos S. Cleidocranial dysplasia: Clinical and molecular genetics. J Med Genet. 1999;36:177–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee C, McCabe LR, Choi JY, Hiebert SW, Stein JL, Stein GS, et al. Runt homology domain proteins in osteoblast differentiation: AML3/CBFA1 is a major component of a bone-specific complex. J Cell Biochem. 1997;66:1–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19970701)66:1<1::aid-jcb1>3.0.co;2-v. doi:10.1002/(SICI).1097-4644(19970701) 66:1<1:AID-JCB1>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee B, Thirunavukkarasu K, Zhou L, Pastore L, Baldini A, Hecht J, et al. Missense mutations abolishing DNA binding of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor OSF2/CBFA1 in cleidocranial dysplasia. Nat Genet. 1997;16:307–10. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-307. doi:10.1038/ng0797-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otto F, Thornell AP, Crompton T, Denzel A, Gilmour KC, Rosewell IR, et al. Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell. 1997;89:765–71. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80259-7. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mundlos S, Otto F, Mundlos C, Mulliken JB, Aylsworth AS, Albright S, et al. Mutations involving the transcription factor CBFA1 cause cleidocranial dysplasia. Cell. 1997;89:773–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80260-3. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, et al. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89:755–64. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamamoto M, Machida J, Miyachi H, Ono T, Nakayama A, Shimozato K, et al. Anovel mutation in the C-terminal region of RUNX2/CBFA1 distal to the DNA-binding runt domain in a Japanese patient with cleidocranial dysplasia. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:434–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.09.025. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida T, Kanegane H, Osato M, Yanagida M, Miyawaki T, Ito Y, et al. Functional analysis of RUNX2 mutations in Japanese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia demonstrates novel genotype-phenotype correlations. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:724–38. doi: 10.1086/342717. doi:10.1086/342717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quack I, Vonderstrass B, Stock M, Aylsworth AS, Becker A, Brueton L, et al. Mutation analysis of core binding factor A1 in patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1268–78. doi: 10.1086/302622. doi:10.1086/302622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaidi SK, Javed A, Choi JY, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, et al. Aspecific targeting signal directs Runx2/Cbfa1 to subnuclear domains and contributes to transactivation of the osteocalcin gene. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(Pt 17):3093–102. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.17.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang YW, Yasui N, Ito K, Huang G, Fujii M, Hanai J, et al. ARUNX2/PEBP2alpha A/CBFA1 mutation displaying impaired transactivation and Smad interaction in cleidocranial dysplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10549–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180309597. doi:10.1073/pnas.180309597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo Muzio L, Tetè S, Mastrangelo F, Cazzolla AP, Lacaita MG, Margaglione M, et al. Anovel mutation of gene CBFA1/RUNX2 in cleidocranial dysplasia. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2007;37:115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xuan D, Li S, Zhang X, Hu F, Lin L, Wang C, et al. Mutations in the RUNX2 gene in Chinese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;38:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tessa A, Salvi S, Casali C, Garavelli L, Digilio MC, Dotti MT, et al. Six novel mutations of the RUNX2 gene in Italian patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:104. doi: 10.1002/humu.9155. doi:10.1002/humu.9155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham ML, Seto ML, Hing AV, Bull MJ, Hopkin RJ, Leppig KA. Cleidocranial dysplasia with severe parietal bone dysplasia:C-terminal RUNX2 mutations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76:78–85. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20231. doi:10.1002/bdra.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee C, Jung HS, Baek JA, Leem DH, Ko SO. Manifestation and treatment in a cleidocranial dysplasia patient with a RUNX2 (T420I) mutation. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;37:41. doi: 10.1186/s40902-015-0042-0. doi:10.1186/s40902-015-0042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Javed A, Guo B, Hiebert S, Choi JY, Green J, Zhao SC, et al. Groucho/TLE/R-esp proteins associate with the nuclear matrix and repress RUNX (CBF (alpha)/AML/PEBP2(alpha)) dependent activation of tissue-specific gene transcription. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 12):2221–31. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young DW, Hassan MQ, Pratap J, Galindo M, Zaidi SK, Lee SH, et al. Mitotic occupancy and lineage-specific transcriptional control of rRNA genes by Runx2. Nature. 2007;445:442–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05473. doi:10.1038/nature05473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang L, Guo B, Javed A, Choi JY, Hiebert S, Lian JB, et al. Crystal structure of the nuclear matrix targeting signal of the transcription factor acute myelogenous leukemia-1/polyoma enhancer-binding protein 2alphaB/core binding factor alpha2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33580–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afzal F, Pratap J, Ito K, Ito Y, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, et al. Smad function and intranuclear targeting share a Runx2 motif required for osteogenic lineage induction and BMP2 responsive transcription. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:63–72. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20258. doi:10.1002/jcp.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westendorf JJ, Zaidi SK, Cascino JE, Kahler R, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, et al. Runx2 (Cbfa1, AML-3) interacts with histone deacetylase 6 and represses the p21(CIP1/WAF1) promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7982–92. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7982-7992.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen G, Courey AJ. Groucho/TLE family proteins and transcriptional repression. Gene. 2000;249:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00161-x. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suda N, Hamada T, Hattori M, Torii C, Kosaki K, Moriyama K. Diversity of supernumerary tooth formation in siblings with cleidocranial dysplasia having identical mutation in RUNX2:Possible involvement of non-genetic or epigenetic regulation. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2007;10:222–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2007.00404.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-6343.2007.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suda N, Hattori M, Kosaki K, Banshodani A, Kozai K, Tanimoto K, et al. Correlation between genotype and supernumerary tooth formation in cleidocranial dysplasia. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2010;13:197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2010.01495.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-6343.2010.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bufalino A, Paranaíba LM, Gouvêa AF, Gueiros LA, Martelli-Júnior H, Junior JJ, et al. Cleidocranial dysplasia: Oral features and genetic analysis of 11 patients. Oral Dis. 2012;18:184–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01862.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryoo HM, Kang HY, Lee SK, Lee KE, Kim JW. RUNX2 mutations in cleidocranial dysplasia patients. Oral Dis. 2010;16:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01623.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang C, Zheng S, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Zhu J, Ge L. Mutational analysis of RUNX2 gene in Chinese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Mutagenesis. 2010;25:589–94. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geq044. doi:10.1093/mutage/geq044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding B, Li C, Xuan K, Liu N, Tang L, Liu Y, et al. The effect of the cleidocranial dysplasia-related novel 1116_1119insC mutation in the RUNX2 gene on the biological function of mesenchymal cells. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56:180–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.01.009. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KE, Seymen F, Ko J, Yildirim M, Tuna EB, Gencay K, et al. RUNX2 mutations in cleidocranial dysplasia. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:4567–74. doi: 10.4238/2013.October.15.5. doi:10.4238/2013.October.15.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]