Abstract

Low erucic acid is a major breeding target to improve the edible oil quality in Brassica juncea. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in fatty acid elongase 1 (FAE1.1 and FAE1.2) gene was exploited to expedite the breeding program. The paralogs of FAE1 gene were sequenced from low erucic acid genotype Pusa Mustard 30 and SNPs were identified through homologous alignment with sequence downloaded from NCBI GenBank. Two SNPs in FAE1.1 at position 591 and 1265 and one in FAE1.2 at 237 were found polymorphic among low and high erucic acid genotypes. These SNPs either create or change the recognition site of restriction enzymes. Transition of a single nucleotide at position 591 and 1265 in FAE1.1, and at position 237 in FAE1.2, leads to a change in the recognition site of Hpy99I, BglII and MnlI restriction enzymes, respectively. Two CAPS markers for FAE1.1 and one for FAE1.2 were developed to differentiate low and high erucic acid genotypes. The efficiency of these CAPS markers was found 100 per cent when validated in Brassica juncea, and B. nigra genotypes and used in back-cross breeding. These CAPS markers will facilitate in marker-assisted selection for improvement of oil quality in Brassica juncea.

Keywords: erucic acid, FAE1, CAPS, SNP, Brassica juncea

Introduction

Improved oil quality coupled with high yield is essential in any oilseed crop. Low cost edible oil from rapeseed mustard (Brassica spp.) is preferred by resource poor families in Asia and Africa. Indian mustard (Brassica juncea), occupying more than 80 per cent of the total area of rapeseed mustard in India, is predominantly used for oil extraction and consumption in most parts of the country. Despite possessing very low amount of polyunsaturated and saturated fatty acid as compared to other edible oils, the high concentration (35–50%) of erucic acid (C22:1) is a major disadvantage to Indian mustard oil. Presence of high erucic acid in edible oil makes it nutritionally undesirable for human consumption as it causes myocardial infarction and increased blood cholesterol (Mortuza et al. 2006, Renard and Mcgregor 1992). On the other hand, the reduction in erucic acid content increases the oleic acid and imparts better ratio of linoleic and linolenic acids in seed oil (Jagannath et al. 2011). As per the international norms, erucic acid should be less than 2 per cent of the total fatty acids. It is therefore, imperative to reduce the erucic acid level to less than 2 per cent in seed oil for better human health, especially for the resource poor consumers. The first source identified for Low Erucic Acid (LEA) content in B. juncea was ‘Zero Erucic Mustard’ (Zem) (Kirk and Oram 1978). This genotype and its derivatives were used in breeding programs for development of LEA cultivars through phenotypic selection following tedious biochemical assay. Studies have now confirmed that erucic acid content is controlled by fatty acid elongase 1 (FAE1) gene that encodes the enzyme β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (KCS) in erucic acid biosynthesis pathway and catalyzes the first four enzymatic reactions in synthesis of very long chain monounsaturated fatty acids (VLCMFAs) (Gupta et al. 2004, James et al. 1995, Millar and Kunst 1997). The mutation in FAE1 gene leads to the loss of function in enzymatic activity and reduces the accumulation of VLCMFAs in seeds (Katavic et al. 2002, Roscoe et al. 2001). In many cultivars of B. napus, a frame shift mutation occurred due to four base pair deletion in the FAE1, which leads to the premature stop of the translation after the 466th amino acid residue (Wu et al. 2008). Similarly, a reverse mutation from the phenylalanine to a serine residue at 282 in FAE1 gene of LEA cultivar ‘ORO’ through site directed mutagenesis restored the elongase activity and erucic acid formation (Katavic et al. 2002). The diploid Brassica species (B. rapa and B. nigra) have one copy of FAE1 gene while the amphidiploid species (B. napus and B. juncea) have two copies with additive effect (Gupta et al. 2004, Lühs et al. 1999, Yan et al. 2015). Several reports dealing with the mapping of FAE1 loci in B. napus and B. rapa are available, however, the information about the location in B. juncea is scanty. The FAE1 paralogues (designated as FAE1.1 and FAE1.2) are located on chromosome A8 and C3 in B. napus (Ecke et al. 1995, Qiu et al. 2006), whereas, in B. juncea, these paralogues were mapped on LG17 and LG3 (Gupta et al. 2004). The LG17 is corresponding to chromosome A8 but the location of FAE1.2 is still unknown. The FAE1 gene is 1521 bp long without introns and encodes a protein of 507 amino acids (Xu et al. 2010). Several SNPs were reported between LEA and high erucic acid (HEA) genotypes in B. napus and B. rapa (Wang et al. 2010, Wu et al. 2008, Yan et al. 2015). Gupta et al. (2004) found substitution-type single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 to distinguish low erucic from high erucic types in B. juncea.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common type of variation in DNA (Brookes 1999). SNPs which include single base substitution and small insertions/deletions, are the smallest unit of inheritance and can be used as perfect molecular markers when identified within genes underlying observed traits (Lv et al. 2013, Uribe et al. 2014). SNP variations could involve four different nucleotides at a particular site leading to only two different possible combinations (Cho et al. 2015, Yan et al. 2015). The abundance, relative stability, ubiquity and interspersed nature of SNPs make them ideal candidate molecular markers for the construction of high-density genetic maps, quantitative trait loci (QTL) fine mapping, marker-assisted breeding and genetic association studies (Rafalski 2002). In addition, SNPs located in known genes provide a fast alternative to analyze the fate of agronomically important alleles in breeding populations, thus providing functional markers (Fusari et al. 2008). Though, numerous SNP genotyping assays are available such as Taqman, single-base extension, allele specific primer extension and direct hybridization, but these assays require specialized detection equipments (Lee et al. 2004). The PCR and simple gel based markers, thus, would be more advantageous in marker-assisted breeding. Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequence (CAPS) markers where the single nucleotide change disrupts or creates a restriction enzyme recognition site, allow the conversion of single nucleotide polymorphisms into a marker through PCR and restriction endonuclease (Di et al. 2015, Michaels and Amasino 1998). Recently, a dCAPS marker was developed and used in marker-assisted selection for low erucic acid in B. rapa (Karim et al. 2016). Since Brassica juncea has two paralogs of this gene, there is a need to develop corresponding CAPS for both of them. Once these markers are developed, the trait can be precisely transferred to any genetic background without the tedious and time taking biochemical assay. Therefore, this study was planned to develop functional CAPS markers based on SNPs present in the candidate gene FAE1, validate and evaluate the efficiency of CAPS markers in differentiating LEA and HEA genotypes and utilize them in Marker-Assisted Backcross Breeding (MABB). The outcome from this study, in form of information and material, shall help in improving efficiency of the selection process and development of improved genotypes with LEA.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Eighteen genotypes of B. juncea (AABB) maintained at Division of Genetics ICAR-IARI and three of diploid B. nigra (BB) collected from ICAR-NRCPB, New Delhi were taken for this study. Two back cross populations (BC1F1) were developed by crossing LEA varieties Pusa Mustard 24 (PM24) and Pusa Mustard 30 (PM30) with HEA varieties Pusa Vijay and Pusa Bold (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genotyping for FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes and erucic acid content in different genotypes

| Species | Genotype | Erucic acid content (%) | Genotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| FAE1.1 (E1) | FAE1.2 (E2) | |||

| B. juncea (Indian genotypes) | PM24 | 0.25 | e1e1 | e2 e2 |

| PM30 | 0.21 | e1e1 | e2 e2 | |

| PDZ-1 | 0.13 | e1e1 | e2 e2 | |

| RCL-1 | 0.25 | e1e1 | e2 e2 | |

| RCL-2 | 0.31 | e1e1 | e2 e2 | |

| RCL-3 | 0.24 | e1e1 | e2 e2 | |

| Pusa Vijay | 39.12 | E1E1 | E2 E2 | |

| Pusa Bold | 43.1 | E1E1 | E2 E2 | |

| NRCDR-02 | 38.26 | E1E1 | E2 E2 | |

| DRMRIJ 31 | 35.15 | E1E1 | E2 E2 | |

| Laxmi | 42.5 | E1E1 | E2 E2 | |

| RH0749 | 39.74 | E1E1 | E2 E2 | |

| LS-1 | 27.42 | E1E1 | e2 e2 | |

| BioYSR | 22.93 | E1E1 | E2 E2 | |

| Heera | 0.13 | e1e1 | e2 e2 | |

|

| ||||

| B. juncea (Exotic genotypes) | EC 597325 | 0.20 | e1e1 | e2 e2 |

| Donskaja | 14.7 | e1e1 | E2 E2 | |

| BEC144 | 23.79 | e1e1 | E2 E2 | |

|

| ||||

| B. nigra | NG1 | 24.3 | – | E2E2 |

| NG2 | 32.02 | – | E2E2 | |

| NG3 | 30.55 | – | E2E2 | |

Molecular analysis

DNA of each individual genotype was extracted from young expanding leaf tissue following the standard cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol (Doyle and Doyle 1990). DNA was quantified using nanodrop (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Scientific, USA) and quality was examined by electrophoresis. The DNA was diluted to a final concentration of 20 ng/μl with HPLC grade water and stored at −20°C for PCR amplifications.

Sequencing of FAE1 paralogs genes and development of CAPS

The full-length FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes from Pusa Mustard 30, a low erucic acid genotype of B. juncea, were amplified using forward and reverse primers 5′ATG ACG TCC ATT AAC GTA AAG CTCC3′ and 5′ATT AGG ACC GAC CGT TTT GGA CA3′ (Gupta et al. 2004), cloned and sequenced. Both these sequences were aligned with the sequences of B. juncea genotypes present in the NCBI GenBank (KP074955, KP074953, KP074949, KP074963, AF274750, AJ558197, AJ558198, AF274750). SNPs in these amplified DNA fragments were also confirmed with those identified by Gupta et al. (2004). The SNPs at position 591 and 1265 in FAE1.1 were found polymorphic between the LEA and HEA genotypes. Similarly, SNP at position 237 of FAE1.2 for low erucic acid was found polymorphic between genotypes having high and low erucic acid content. Using these SNPs (Table 1), CAPS primers were designed for both the genes. Two independent CAPS markers for FAE1.1 and one CAPS marker for FAE1.2 were developed. For detecting CAPS markers, amplification reactions were carried out in a total volume of 15 μl containing 50 ng template DNA, 1X PCR buffer, 0.1 mM of each dNTP, 1U Taq DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies, USA) and 10 pmol of each forward and reverse primer. Conditions of the PCR amplification were as follows: 94°C for 4 min, then 35 cycles each at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The amplified PCR products were digested using suitable restriction endonuclease enzyme in a final volume of 20 μl according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Table 1.

Details of the primers and restriction enzymes used in CAPS marker development

| Gene | Primer name | Primer sequence | Restriction enzyme | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAE1.1 | CAPS591 | F-TCGTGGCTTGACTTCTTGAG R-GGACCTATTATCACCAGCGTAAA |

Hpy99 I | 432 |

| CAPS1265 | F-ACGTTAGGTCCGTTGATTCTTC R-GGGTATCTGTCGATGCAATGT |

BG1II | 427 | |

| FAE1.2 | CAPS237 | F-TAACCATCGCTCCACTCTTTG R-TCAAGAAGTCAAGCCACGAC |

MnlI | 219 |

Phenotyping for erucic acid content

Erucic acid content in the seeds of twenty one genotypes and individual plants of BC1F1 generation were analyzed by a gas liquid chromatograph (Perkin Elmer Clarus 600) using flame ionization detector (FID). The conditions maintained were column temperature: 150°C–270°C, Injector Temperature: 250°C and Detector temperature: 250°C. GLC was programmed for the temperature at the rate of 10°C per minute increase and finally it was maintained at 270°C. Peaks of the fatty acid methyl esters were identified by comparing their retention time with that of the known standards, run under similar separation conditions (Sujata et al. 2008).

Results

Phenotyping of B. juncea genotypes

The erucic acid content in the oil of all B. juncea genotypes are given in Table 2. Eight single zero Indian mustard genotypes viz., PM24, PM30, PDZ-1, RCL-1, RCL-2, RCL-3, EC 597325 and Heera had erucic acid less than 2 per cent, six (NRCDR-02, DRMRIJ 31, Laxmi, Pusa Vijay, Pusa Bold and RH0749) had high erucic acid content (30–45%) while two genotypes [BioYSR and LS-1 (selection from Laxmi)] had intermediate levels (20–30%) of erucic acid. The yellow seeded, white rust resistant exotic genotypes BEC144 and Donskaja revealed intermediate erucic acid content, while exotic lines EC 597325 had less than 2 per cent erucic acid. All the three B. nigra genotypes were found to be high in erucic acid content (Table 2).

Two BC1F1 populations, developed from the cross [(PM24 × Pusa Vijay) × PM24] and [(PM30 × Pusa Bold) × Pusa Mustard 30], comprising of 136 and 122 individuals respectively, were phenotyped for erucic acid content. The segregation pattern of the erucic acid trait in both the BC1F1 populations fit well in 1:2:1 ratio (χ2 = 4.536 and 0.972, respectively) (Table 3), indicating digenic inheritance. The heterozygotes for these genes expressed an intermediate level of erucic acid content, as compared to homozygous individuals, indicating additive gene action. As reported by Gupta et al. (2004), FAE1.1 gene contributes more to the phenotype as compared to FAE1.2. Our results confirmed that plants heterozygous for FAE1.1 gene were, in general, having more erucic acid content (12.28 ± 0.45) than the plants which were heterozygous for FAE1.2 gene (7.67 ± 0.8%).

Table 3.

Genotyping and phenotyping of BC1F1 populations for erucic acid trait

| BC1F1 population of cross | Total plants | Erucic acid content (%) | χ2 value | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| <2.0% | 2–14% | 15–31% | ||||

| PM24 × P. Vijay | 136 | 31 | 78 | 27 | 3.176 | 0.2043 |

| PM 30 × P. Bold | 122 | 29 | 69 | 24 | 2.508 | 0.2853 |

| Genotype | e1e1e2e2 | E1e1e2e2/e1e1E2e2 | E1e1E2e2 | |||

SNP detection

The PCR amplification of FAE1 gene produced a single amplicon in both low and high erucic acid genotypes. However, two different sequences were identified on sequencing the clones of PM30, confirming earlier reported SNPs (Gupta et al. 2004). The FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 gene sequences of PM30 were aligned with the sequence of erucic acid genes from B. juncea genotypes downloaded from NCBI GenBank ((KP074955, KP074953, KP074949, KP074963, AF274750, AJ558197, AJ558198, AF274750). Several SNPs were found and majority of them were same as reported by Gupta et al. (2004). Allele-specific primers for these SNPs, as suggested by Liu et al. (2012), and promoter based marker developed by Yan et al. (2015) in B. rapa failed to distinguish the low and high erucic acid containing genotypes.

Development of CAPS markers

The identified SNPs were converted into CAPS markers for their deployment in breeding programs. Out of seven earlier reported SNPs, base substitution from A to G at position 591 in FAE1.1 gene was found to be polymorphic between LEA and HEA genotypes. This transition creates the restriction site recognized by enzyme Hpy99I in HEA genotypes. However, there are two other restriction sites for Hpy99I enzyme in FAE1.1 gene. The primers were designed meticulously to have only one restriction site for Hpy99I enzyme in the amplicon. Similarly, at position 1265 in FAE1.1 gene a transition from C to T leads to change the cleavage site of BglII restriction enzyme.

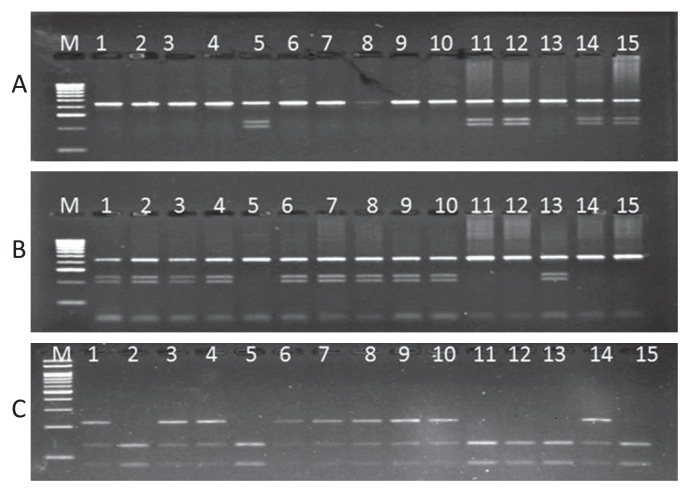

Out of the three earlier reported SNPs in FAE1.2 gene, the one at position 237, leads to a change in the recognition site of restriction enzyme MnlI in LEA genotypes. This restriction enzyme MnlI has seven restriction sites in FAE1.2. Every precaution was taken in designing the primers that have only one restriction site in the amplicon. The 219 bp amplicon of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 gene was digested with the enzyme MnlI. In HEA genotypes, it produced two fragments of size 87 bp and 112 bp, whereas, in LEA genotypes, FAE1.2 remains undigested and generated three bands (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Detection of SNP591 (A) and SNP 1265 (B) of FAE1.1 and SNP237 (C) of FAE1.2 using CAPS markers in genotypes PM24 (1), BEC144 (2), Heera (3), PM30 (4), BioYSR (5), EC 597325 (6), PDZ-1 (7), RCL-1 (8), RCL-2 (9), RCL-3 (10), NRCDR-02 (11), DRMRIJ 31 (12), Donskaja (13), LS-1 (14) and RH0749 (15).

Validation of CAPS markers

The CAPS markers, developed in this study, were validated in the 21 diverse genotypes possessing variable erucic acid content in their oil (Table 1). All genotypes generated fragments of expected size for each CAPS maker. The CAPS markers for FAE1.1 gene amplified 432 bp and 427 bp fragments for SNP591 (CAPS591) and SNP1265 (CAPS1265) respectively. The primers of CAPS591 and CAPS1265 amplified a single amplicon of same size in both FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes. However, on digestion with restriction enzyme, only FAE1.1 amplicon was digested, while FAE1.2 remains unaffected. On digestion with Hpy99I enzyme the amplicon of CAPS591, generated three fragments: one undigested product of FAE1.2 (432 bp) and two fragments of size 224 and 198 bp of FAE1.1 gene in HEA genotypes, whereas, there was no digestion in LEA genotypes (Fig. 1A). Similarly, on digestion with BglII enzyme for CAPS1265 generated three fragments in LEA genotypes: one undigested fragment of FAE1.2 and two digested products of size 209 bp and 198 bp of FAE1.1, whereas, only one fragment was obtained in HEA genotypes (Fig. 1A, B).

In case of FAE1.2 gene, the SNP237 converted into CAPS237 marker, amplified single amplicon of 219 bp. On digestion with restriction enzyme MnlI, both the alleles of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 were digested in HEA genotypes and produced 87 and 112 bp fragments, whereas, in LEA genotypes, the FAE1.1 allele was digested and FAE1.2 remained undigested. By using CAPS591 and CAPS1265 it is easy to identify homozygous and heterozygous individuals for FAE1.1 gene in breeding population, whereas CAPS237 behave as a dominant marker for FAE1.2 gene (Fig. 1C).

B. nigra genotypes were also screened with these three CAPS markers. These markers generated the same amplicon sizes as were observed in B. juncea genotypes. To detect the SNPs using restriction enzymes, the Hpy99I and BglII enzymes failed to digest, whereas, MnlI completely digested the amplicon. This showed that the B. nigra genotypes have only FAE1.2 gene.

High erucic acid Indian mustard genotypes were having dominant alleles while genotypes having less than 2 per cent erucic acid (LEA) were recessive at both the loci. LS-1 was found to have dominant allele at FAE1.1 locus and recessive at FAE1.2 locus possessed intermediate erucic acid content. Exception was a genotype BioYSR, having an intermediate erucic acid content (22.93%), but dominant alleles at both the loci. The European genotypes, on the other hand, were having erucic acid content as per their haplotype.

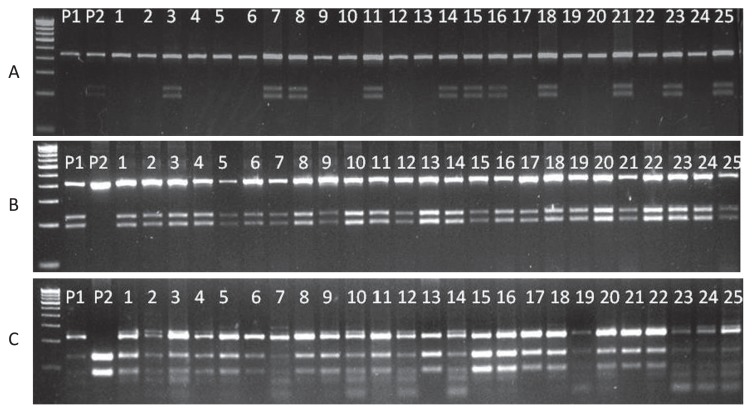

Use of CAPS markers in MAS

A limited back cross breeding program was initiated to improve the traits of agronomic importance in LEA varieties (PM 24 and PM 30) using popular cultivars Pusa Vijay and Pusa Bold. The BC1F1 individuals were genotyped with CAPS markers developed for erucic acid in this study (Fig. 2). Around 136 BC1F1 individuals from the cross (PM 30 × Pusa Vijay) × PM 30 and 122 from (PM 24 × Pusa Bold) × PM 24 were phenotyped for erucic acid content in seed oil (Table 3). Individuals from both the back cross populations were genotyped with above mentioned CAPS markers. The individuals having less than 2 per cent erucic acid were homozygous at both the loci while the intermediate types were identified heterozygous at either of the loci.

Fig. 2.

Amplification patterns of newly developed CAPS markers in BC1F1 individuals derived from the cross between Pusa Mustard 30 (P1; low erucic acid, e1e1e2e2) and Pusa Bold (P2; high in erucic acid, E1E1E2E2). A: Plants 3, 7, 8, 11, 14, 15, 16, 18, 21, 23, and 25 have the dominant allele of FAE1.1 (E1) as shown by the restriction pattern with the CAPS marker CAPS591. B: The digestion pattern with CAPS1265 revealed the presence of recessive allele (e1) in all individuals. C: The restriction pattern with the dominant marker CAPS237 for gene FAE1.2 demonstrated that the individuals were either recessive homozygous (e2e2) or heterozygous (E2e2).

Discussion

The FAE1 gene encoded β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (KCS) enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of very long chain monounsaturated fatty acids (VLCMFA), a major constituent of seed oil (Lühs et al. 1999). The mutation in FAE1 genes results in the loss of function in condensation enzymatic activity during the synthesis of VLCMFA (Katavic et al. 2002). It is well documented that erucic acid trait is governed by two independent genes FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 in allotetraploids B. napus and B. juncea (Bhatia and Alok 2014, Gupta et al. 2004, Yan et al. 2015). Native genotypes of Indian mustard are high (>35–45%) in erucic acid content having both homozygous dominant genes. The exotic LEA genotype, such as EC 597325, has homozygous recessive alleles at both the loci while Donskaja and BEC144 genotypes have recessive alleles at FAE1.1 and dominant homozygous allele at FAE1.2 locus. These genotypes thus, possess intermediate erucic acid content in their oil (14.7% and 23.79%, respectively). Kirk and Hurlstone (1983) also reported that the east European group has intermediate erucic content (<25%) due to presence of dominant alleles for high erucic acid level at one locus only. In contrast, the genotype BioYSR had intermediate levels (22.93%) of erucic acid content in seed oil despite having dominant homozygous alleles at both FAE1 loci. The B. nigra genotypes were found to have intermediate to high erucic acid content despite having only one homozygous dominant gene FAE1.2 (Table 2). The variation in erucic acid content among the genotypes indicated the role of other genomic factors in biosynthesis of erucic acid along with dominant allele at either of the loci. Cao et al. (2010) detected a QTL in B. napus near to FAE1.1 gene with small effect on erucic acid content. In present study, the segregation pattern confirms digenic and additive inheritance of erucic acid trait in the both BC1F1 populations. Several earlier studies have also reported the continuous variation in erucic acid in segregating populations of B. juncea (Pandey et al. 2013, Singh et al. 2015) and B. napus (Cao et al. 2010, Lühs et al. 1999). This phenotypic variation confirms the role of modifiers in biosynthesis of erucic acid. Similar results were found in cereals where the opaque2 mutant in maize requires modifiers to increase the tryptophan and lysine content beyond a certain limit (Holding et al. 2011).

The FAE1.1 is located on chromosome A8 while the position of FAE1.2 is still unknown in B. juncea. Pradhan et al. (2003) and Bhatia and Alok (2014) mapped both these genes on linkage group LG17 and LG3 by using AFLP markers. In B. napus, FAE1 genes are located on chromosome A8 and C3. However, no microsatellite marker has been reported to show linkage with either of the FAE1 genes in B. juncea, which can be used in marker-assisted selection. Yan et al. (2015) observed 24 base AT-rich deletion region in the FAE1 promoter of low erucic acid cultivars of B. rapa (A8) and developed a STS marker (pM120F/pM468R). This marker in our study amplified only in exotic B. juncea genotypes (data not shown).

The sequence of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 are highly similar and only 32 substitution-type single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were observed between these two genes in B. juncea cultivar Varuna (AJ558197.1 and AJ558198.1), whereas, in B. napus, 18 SNPs are found between FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 (Wang et al. 2010). Gupta et al. (2004) detected four SNPs in FAE1.1 and three in FAE1.2 alleles. Out of six SNPs found in B. rapa (Wang et al. 2010), four were also present in B. juncea cultivars. Among the three SNPs present in FAE1.2, the either of the nucleotide was same in the FAE1.1. Only one SNP, present at position 591, could differentiate the FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes. Several SNP genotyping methods e.g. pyrosequencing (Ronaghi et al. 1998), TaqMan assay (Lee et al. 1993), targeting induced local lesions in genomes (McCallum et al. 2000) have been successfully utilized. All these methods are demanding high skills and specific instruments. Even though, the high throughput genotyping techniques like TaqMan have been used to discriminate the alleles on SNPs in many crops (Shi et al. 2015), this marker system will not be able to differentiate the homozygous recessive from heterozygous allele for FAE1.2, because either of the SNP of FAE1.2 is present in FAE1.1. On the other hand, the allele specific-PCR (AP-PCR) SNP detection system has been recommended on low cost grounds, even though the allele-specificity is about 30 per cent to highest 81 per cent (Liu et al. 2012). On PCR amplification with AP-PCR primer, allele specific PCR fails to differentiate the LEA and HEA cultivars on the basis of these SNPs since amplicon was always observed due to presence of two paralogs of this gene.

In a marker-based breeding program, a simple gel based technique is required to save time and improve the efficiency of selection. The CAPS marker system can potentially utilize single nucleotide polymorphism for development of a PCR-based marker. Four SNPs in FAE1.1 and three in FAE1.2 were identified to distinguish low erucic from high erucic types in B. juncea (Gupta et al. 2004). The SNP at position 591 was found highly conserved in FAE1.1 among B. juncea, B. napus and B. rapa genotypes differing in erucic acid content. Moreover, at this position there is single nucleotide difference between FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes in B. juncea and B. napus (Gupta et al. 2004, Wang et al. 2010). This single substitution of nucleotide from G to A in low erucic acid genotypes, leads to a change in the cleavage site of restriction enzyme Hpy99I. The primers were designed in such a way that only one recognition site was present in the amplicon. Similarly, the SNP arising from change of T to C at locus 1265 generates the recognition site for BglII in LEA genotypes. The amplicons generated by CAPS591 and CAPS1265 digested in LEA and HEA genotypes with respective restriction enzymes concluded that all genotypes are homozygous at position 591 and 1265 corresponding FAE1.1 gene. Among the three SNPs reported in FAE1.2 gene, one positioned at 237 was present in recognition site of enzyme MnlI. The substitution of nucleotide A to C, in LEA genotypes, alters the recognition site of MnlI enzyme. Although, this SNP was not observed in B. rapa and B. oleracea (Wang et al. 2010), it proves that the FAE1.2 is B genome specific. On restriction with MnlI enzyme complete digestion of amplicon from FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 was observed in wild type, whereas, in heterozygous or recessive homozygous condition at FAE1.2 locus there would be incomplete digestion. Therefore, CAPS237 could not differentiate the heterozygous and recessive homozygous state at FAE1.2 locus. The marker helps track the recessive allele in heterozygous and recessive homozygous states in the backcross progenies. Once the nuclear background of the recurrent parent is determined, marker-facilitated progeny evaluation, in BC1F2 or successive generations, will help in identification of non-segregating progenies carrying homozygous recessive alleles.

It is evident that the functional CAPS markers developed in this study for FAE1 loci are highly efficient. The use of these three allele-specific functional markers (CAPS237, CAPS591 and CAPS1265) will thus, reduce time, cost and will improve accuracy in the marker-assisted selection for development of LEA Brassica genotypes.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Dept. of Biotechnology and Indian council of Agricultural Research, Govt. of India for the financial assistance to carry out this research.

Literature Cited

- Bhatia, V. and Alok, A. (2014) Molecular marker analysis of the linkage drag around the FAE1 loci of Brassica juncea during conventional backcross breeding. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 17: 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, A.J. (1999) The essence of SNPs. Gene 234: 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z., Tian, F., Wang, N., Jiang, C., Lin, B., Xia, W., Shi, J., Long, Y., Zhang, C. and Meng, J. (2010) Analysis of QTLs for erucic acid and oil content in seeds on A8 chromosome and the linkage drag between the alleles for the two traits in Brassica napus. J. Genet. Genomics 37: 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.I., Ahn, Y.K., Tripathi, S., Kim, J.H., Lee, H.E. and Kim, D.S. (2015) Comparative analysis of disease-linked single nucleotide polymorphic markers from Brassica rapa for their applicability to Brassica oleracea. PLoS ONE 10: e0120163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di, H., Liu, X., Wang, Q., Weng, J., Zhang, L., Li, X. and Wang, Z. (2015) Development of SNP-based dCAPS markers linked to major head smut resistance quantitative trait locus qHS2.09 in maize. Euphytica 202: 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J.J. and Doyle, J.L. (1990) Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12: 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ecke, W., Uzunova, M. and Weißleder, K. (1995) Mapping the genome of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). II. Localization of genes controlling erucic acid synthesis and seed oil content. Theor. Appl. Genet. 91: 972–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusari, C.M., Lia, V.V., Hopp, H.E., Heinz, R.A. and Paniego, N.B. (2008) Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms and analysis of linkage disequilibrium in sunflower elite inbred lines using the candidate gene approach. BMC Plant Biol. 8: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V., Mukhopadhyay, A., Arumugam, N., Sodhi, Y.S., Pental, D. and Pradhan, A.K. (2004) Molecular tagging of erucic acid trait in oilseed mustard (Brassica juncea) by QTL mapping and single nucleotide polymorphisms in FAE1 gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108: 743–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holding, D.R., Hunter, B.G., Klingler, J.P., Wu, S., Guo, X., Gibbon, B.C., Wu, R., Schulze, J.M., Jung, R. and Larkins, B.A. (2011) Characterization of opaque2 modifier QTLs and candidate genes in recombinant inbred lines derived from the K0326Y quality protein maize inbred. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122: 783–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannath, A., Sodhi, Y.S., Gupta, V., Mukhopadhyay, A., Arumugam, N., Singh, I., Rohtagi, S., Burma, P., Pradhan, A.K. and Pental, D. (2011) Eliminating expression of erucic acid-encoding loci allows the identification of ‘hidden’ QTL contributing to oil quality fractions and oil content in Brassica juncea (Indian mustard). Theor. Appl. Genet. 122: 1091–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, D.W., Lim, E., Keller, J., Plooy, I., Ralston, E. and Dooner, H.K. (1995) Directed tagging of the Arabidopsis fatty acid elongation 1 (FAE1) gene with the maize transposon activator. Plant Cell 7: 309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim, M.M., Tonu, N.N., Hossain, M.S., Funaki, T., Meah, M.B., Hossain, D.M., Asad ud-doullah, M., Fukai, E. and Okazaki, K. (2016) Marker-assisted selection of low erucic acid quantity in short duration Brassica rapa. Euphytica 208: 535–544. [Google Scholar]

- Katavic, V., Mietkiewska, E., Barton, D.L., Giblin, E.M., Reed, D.W. and Taylor, D.C. (2002) Restoring enzyme activity in nonfunctional low erucic acid Brassica napus fatty acid elongase 1 by a single amino acid substitution. Eur. J. Biochem. 269: 5625–5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, J.T.O. and Oram, R.N. (1978) Mustards as possible oil and protein crops for Australia. J. Aust. Inst. Agric. Sci. 44: 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, J.T.O. and Hurlstone, C.G. (1983) Variation and inheritance of erucic acid content in Brassica juncea. Z Pflanzenzuchtg 90: 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.G., Connell, C.R. and Bloch, W. (1993) Allelic discrimination by nick-translation PCR with fluorogenic probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 21: 3761–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H., Walker, D.R., Cregan, P.B. and Boerma, H.R. (2004) Comparison of four flow cytometric SNP detection assays and their use in plant improvement. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110: 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., Huang, S., Sun, M., Liu, S., Liu, Y., Wang, W., Zhang, X., Wang, H. and Hua, W. (2012) An improved allele-specific PCR primer design method for SNP marker analysis and its application. Plant Methods 8: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lühs, W.W., Voss, A., Seyis, F. and Friedt, W. (1999) Molecular genetics of erucic acid content in the genus Brassica. In: Proc. 10th Intern. Rapeseed Congr. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, H.H., Yang, L.M., Kang, J.G., Wang, Q.B., Wang, X.W., Fang, Z.Y., Liu, Y.M., Zhuang, M., Zhang, Y.Y., Lin, Y.et al. (2013) Development of InDel markers linked to Fusarium wilt resistance in cabbage. Mol. Breed. 32: 961–967. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, C.M., Comai, L., Greene, E.A. and Henikoff, S. (2000) Targeting induced local lesions in genomes (TILLING) for plant functional genomics. Plant Physiol. 123: 439–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, S.D. and Amasino, R.M. (1998) A robust method for detecting single nucleotide changes as polymorphic markers by PCR. Plant J. 14: 381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar, A.A. and Kunst, L. (1997) Very-long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis is controlled through the expression and specificity of the condensing enzyme. Plant J. 12: 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortuza, M.G., Dutta, P.C. and Das, M.L. (2006) Erucic acid content in some rapeseed/mustard cultivars developed in Bangladesh. J. Sci. Food Agric. 86: 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S., Kabdal, M. and Tripathi, M.K. (2013) Study of inheritance of erucic acid in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L. Czern & Coss). Octa Journal of Biosciences 1: 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, A.K., Gupta, V., Mukhopadhyay, M., Arumugam, N., Sodhi, Y.S. and Pental, D. (2003) A high-density linkage map in Brassica juncea (Indian mustard) using AFLP and RFLP markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106: 607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, D., Morgan, C., Shi, J., Long, Y., Liu, J., Li, R., Zhuang, X., Wang, Y., Tan, X., Dietrich, E.et al. (2006) A comparative linkage map of oilseed rape and its use for QTL analysis of seed oil and erucic acid content. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114: 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafalski, A. (2002) Applications of single nucleotide polymorphisms in crop genetics. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5: 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard, S. and Mcgregor, S. (1992) Antithrombogenic effect of erucic acid poor rapeseed oil in the rats. Rev. Fr. Crop Cros. 23: 393–396. [Google Scholar]

- Ronaghi, M., Uhlen, M. and Nyren, P.A. (1998) Sequencing method based on real-time pyrophosphate. Science 281: 363–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe, T.J., Lessire, R., Puyaubert, J., Renard, M. and Delseny, M. (2001) Mutations in the fatty acid elongation 1 gene are associated with a loss of β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase activity in low erucic acid rapeseed. FEBS Lett. 492: 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z., Bachleda, N., Pham, A.T., Bilyeu, K., Shannon, G., Niguyen, H. and Li, Z. (2015) High-throughput and functional SNP detection assays for oleic and linolenic acids in soybean. Mol. Breed. 35: 176. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J., Yadava, D.K., Vasudev, S., Singh, N., Muthusamy, V. and Prabhu, K.V. (2015) Inheritance of low erucic acid in Indian mustard [Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. and Coss.]. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 75: 264–266. [Google Scholar]

- Sujata, V., Yadava, D.K., Divya, M., Tanwar, R.S. and Prabhu, K.V. (2008) A simplified method for preparation of fatty acid methyl esters of Brassica oil. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 68: 456–458. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, P., Jansky, S. and Halterman, D. (2014) Two CAPS markers predict Verticillium wilt resistance in wild Solanum species. Mol. Breed. 33: 465–476. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N., Shi, L., Tian, F., Ning, H., Wu, X., Long, Y. and Meng, J. (2010) Assessment of FAE1 polymorphisms in three Brassica species using EcoTILLING and their association with differences in seed erucic acid contents. BMC Plant Biol. 10: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G., Wu, Y., Xiao, L., Li, X. and Lu, C. (2008) Zero erucic acid trait of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) results from a deletion of four base pairs in the fatty acid elongase 1 gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 116: 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, A., Huang, Z., Ma, C., Xiao, E., Zhang, X., Tu, J. and Fu, T. (2010) FAE1 sequence characteristics and its relationship with erucic acid content in Brassica juncea. Acta Agron. Sin. 36: 794–800. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G., Li, D., Cai, M., Gao, G., Chen, B., Xu, K., Li, J., Li, F., Wang, N., Qiao, J.et al. (2015) Characterization of FAE1 in the zero erucic acid germplasm of Brassica rapa L. Breed. Sci. 65: 257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]