Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the effectiveness of antimicrobial blue light (aBL) as an alternative or adjunctive therapeutic for infectious keratitis.

Methods

We developed an ex vivo rabbit model and an in vivo mouse model of infectious keratitis. A bioluminescent strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was used as the causative pathogen, allowing noninvasive monitoring of the extent of infection in real time via bioluminescence imaging. Quantitation of bacterial luminescence was correlated to colony-forming units (CFU). Using the ex vivo and in vivo models, the effectiveness of aBL (415 nm) for the treatment of keratitis was evaluated as a function of radiant exposure when aBL was delivered at 6 or 24 hours after bacterial inoculation. The aBL exposures calculated to reach the retina were compared to the American National Standards Institute standards to estimate aBL retinal safety.

Results

Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis fully developed in both the ex vivo and in vivo models at 24 hours post inoculation. Bacterial luminescence in the infected corneas correlated linearly to CFU (R2 = 0.921). Bacterial burden in the infected corneas was rapidly and significantly reduced (>2-log10) both ex vivo and in vivo after a single exposure of aBL. Recurrence of infection was observed in the aBL-treated mice at 24 hours after aBL exposure. The aBL toxicity to the retina is largely dependent on the aBL transmission of the cornea.

Conclusions

Antimicrobial blue light is a potential alternative or adjunctive therapeutic for infectious keratitis. Further studies of corneal and retinal safety using large animal models, in which the ocular anatomies are similar to that of humans, are warranted.

Keywords: antimicrobial blue light, keratitis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, mouse model, rabbit model, bioluminescence imaging

Infectious keratitis is a potentially blinding ocular condition of the cornea. According to a recent report released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), each year in the United States there are approximately 1 million clinical visits for keratitis, translating into an estimated total cost of $175 million per year.1 The risk factors for infectious keratitis include ocular trauma, contact lens wear, recent ocular surgery, preexisting ocular surface disease, dry eyes, lid deformity, corneal sensational impairment, chronic use of topical steroids, and systemic immunosuppression.2 The common causative pathogens of infectious keratitis are Pseudomonas aeruginosa,2–5 Staphylococcus aureus,2,5–7 Streptococcus pneumonia,8,9 and Fusarium solani.10,11 Treatment of infectious keratitis must be rapidly instituted to minimize the destruction of corneal tissue, limit the extent of corneal scarring, and prevent vision loss. The current standard of care for the treatment of infectious keratitis is the use of topical or systemic antibiotics.12,13 However, the clinical management of keratitis has been significantly complicated by the increasing emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens.2–8,11,14 Pathogens replicate rapidly, and a mutation that helps a pathogen survive in the presence of antibiotic(s) will quickly become predominant throughout the microbial population, rendering infections that cannot be treated with available antibiotics. There is, consequently, a pressing need for the development of alternative treatment regimens to tackle drug resistance in infectious keratitis.

A novel light-based antimicrobial approach, antimicrobial blue light (aBL), has attracted increasing attention due to its intrinsic antimicrobial effect without the involvement of exogenous photosensitizers.15–17 It also appears that pathogens are less able to develop resistance to aBL than to traditional antibiotics due to the multitarget characteristic of aBL.15,18 The mechanism of action of aBL is still not fully understood. A common hypothesis is that aBL excites the naturally occurring endogenous porphyrins or/and flavins in microbial cells and subsequently leads to the production of cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS).15 The transparency of the cornea and the superficial nature of keratitis make keratitis an ideal candidate for aBL therapy.

Despite of the advantages of aBL, this optical approach has yet to become established as a treatment of infections. In the present study, we investigated the effectiveness of aBL (415 nm) for the treatment of infectious keratitis using an ex vivo rabbit model and an in vivo mouse model. A bioluminescent strain of P. aeruginosa was used as the causative pathogen, allowing noninvasive monitoring of the extent of infection in real time. Because sufficiently high exposure to aBL is toxic to the retina, we compared the retinal exposure during aBL irradiation to the safety threshold published by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI; American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers 136.1).19 Our study demonstrated that bacteria were rapidly and significantly reduced both ex vivo and in vivo after a single exposure of aBL, and the aBL toxicity to the retina is largely dependent on the aBL transmission of the cornea.

Methods

Blue Light Source

Antimicrobial blue light was delivered using a light-emitting diode (LED) (Vielight, Inc., Toronto, Canada) with peak emission at 415 nm and full-width half maximum of 20 nm. The LED was mounted on a heat sink to prevent thermal effects. The irradiance on the corneal surface was 100 mW/cm2 throughout the study as measured using a PM100D power/energy meter (Thorlabs, Inc., Newton, NJ, USA). Varying aBL exposures were delivered by varying the irradiation time.

Bacterial Strain

Pseudomonas aeruginosa American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 19660 (strain 180), an ExoU expression strain,20 was used as the representative causative pathogen. The strain was made bioluminescent by transfecting lux operon into the bacterial strain as described previously.21 This allowed noninvasive and real-time monitoring of bacterial bioluminescence, which is related to the corresponding colony-forming units (CFU) of bacteria, by using bioluminescence imaging.22 Bacteria were routinely grown in brain–heart infusion (BHI) medium (Fisher Scientific, Agawam, MA, USA) supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin in an orbital incubator (37°C; 0.14g; New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NJ, USA).

aBL Therapy for Keratitis in the Ex Vivo Rabbit Model

Enucleated whole mature New Zealand white rabbit eyes with clear corneas were purchased from Pel-Freez Biologicals (Rogers, AR, USA) and thawed on the day of the experiment. The central area of corneal epithelium (11-mm diameter) was surgically removed using a sterile surgical blade. Subsequently, a 20-μL aliquot of bacterial suspension containing 2 × 106 CFU P. aeruginosa in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was topically inoculated onto the de-epithelized corneas. The infected eyes were then incubated at 37°C for 6 or 24 hours. Bioluminescence imaging was performed to monitor the extent of infection.

Eighteen infected ex vivo rabbit eyes were randomly divided into three groups of six eyes each. Two groups were subjected to aBL exposure and the other group served as the untreated control. Antimicrobial blue light was delivered at 6 or 24 hours after bacterial inoculation (six rabbit eyes for each time point) to investigate its effectiveness against early-stage or fully developed infections.

aBL Therapy for Keratitis in the In Vivo Mouse Model

Female C57BL/6 mice, aged 8 weeks and weighing 18 to 20 g, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Massachusetts General Hospital (protocol no. 2014N000016) and were in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Under anesthesia, corneas of mice were scarified using a 30.5-guage needle to produce three parallel incisions that did not penetrate beyond the superficial stroma.21 A 5-μL aliquot of bacterial suspension containing 5 × 105 CFU P. aeruginosa in PBS was then topically inoculated onto the wounded area of the corneas. Only one cornea was wounded and infected in each mouse. Bioluminescent imaging was performed to monitor the extent of infection.

Eighteen infected mice were then randomly divided into three groups of six mice each. Two groups were subjected to aBL exposure, and the other group served as the untreated control. Similar to the procedure for the ex vivo study using rabbit models, aBL was delivered at 6 or 24 hours after bacterial inoculation (six mice for each time point) to investigate its effectiveness against early-stage and fully developed infections, respectively.

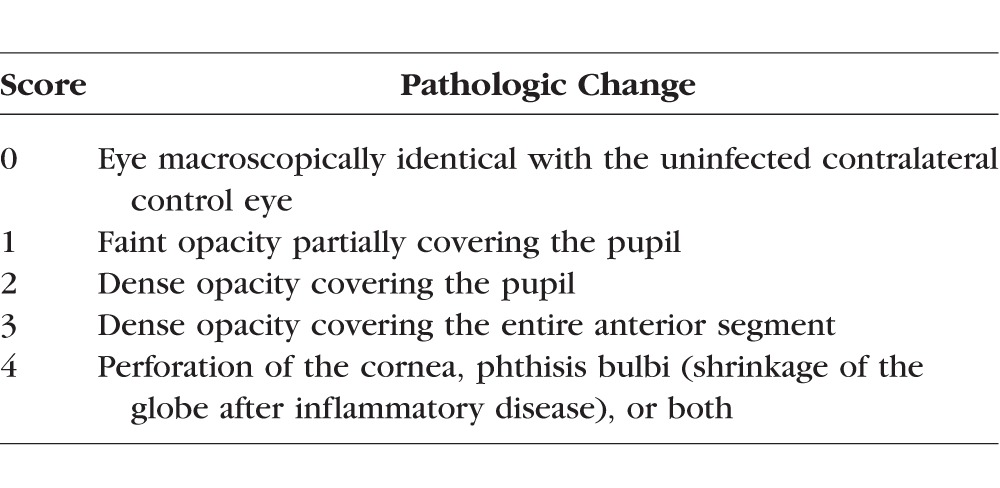

The mouse corneas were also photographed daily using a digital camera (Nikon D90 with a AF Micro Nikkor 60mm 1:2.8D lens; Tokyo, Japan). To statistically analyze the pathologic changes in the corneas, photographs were scored by three ophthalmologists who were unaware of the treatments given. The scoring system used is described in the Table.23

Table 1.

Corneal Pathology Scores of Mice23

Bioluminescence Imaging of Infections

The bacterial luminescence in the infected corneas was detected using a Hamamatsu bioluminescence imaging system (Hamamatsu Photonics KK, Bridgewater, NJ, USA). This system included an intensified charge-coupled device (ICCD) camera (C2400-30H, Hamamatsu) developed for imaging under extremely low light levels, a camera controller, a specimen chamber, and an image processor (C5510-50, Hamamatsu). Rabbit or mouse corneas were placed on an adjustable stage in the specimen chamber, and were positioned directly under the ICCD camera. When set for photon counting, the camera controller's automatic amplification circuit was employed for maximum sensitivity. An integration time of 2 minutes was used for image acquisition. For each measurement, the background signal was subtracted from the bioluminescent signal. The bioluminescence measurement of infections was quantified using Argus 5.0 software (Hamamatsu).

Quantitative Correlation of Bacterial Luminescence to Bacterial CFU in the Infected Corneas

To quantitatively correlate bacterial CFU to the corresponding bacterial luminescence (relative light units: RLU), ex vivo rabbit corneas infected with P. aeruginosa were used. In brief, rabbit corneas were inoculated with a 20-μL aliquot of bacterial suspension containing 2 × 106 CFU P. aeruginosa in PBS. After incubation overnight at 37°C, infected rabbit corneas were exposed, respectively, to varying aBL exposures (0, 36, 72, 108, and 144 J/cm2) and then subjected to bioluminescence imaging. After imaging, each rabbit cornea was homogenized in 1 mL sterile PBS at 4°C. Suspensions were collected and plated on BHI agar after serial 10-fold dilutions.24 Total CFU were counted and plotted versus the corresponding bacterial luminescence measured.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and differences between groups were tested for significance by using an unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test. Differences in corneal pathology scores between different groups of mice were analyzed using the general linear model. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant for all statistical analyses.

Results

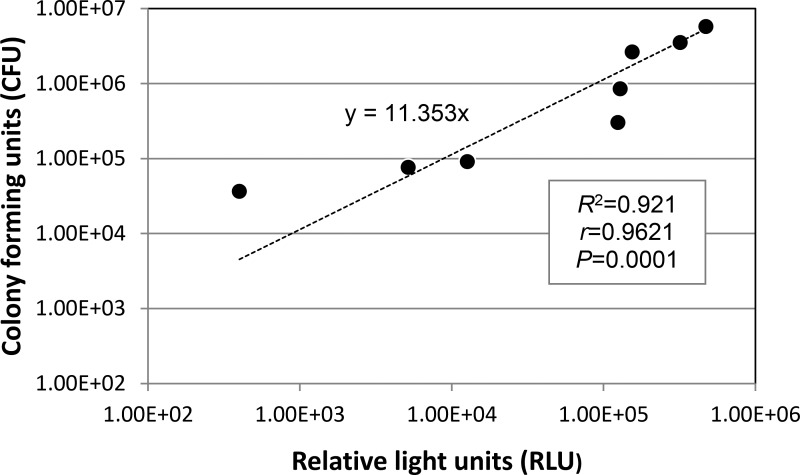

Bacterial Luminescence Was Linearly Correlated to CFU

To test whether measuring the RLU of bacterial bioluminescence in the infected eyes after aBL exposure accurately reported the corresponding bacterial CFU, bacterial luminescence measurements were made after varying radiant exposures of aBL, and bacteria were cultured from the same eyes. Figure 1 shows a fairly good linear correlation (y = 11.353x) between the bacterial luminescence measurement (RLU) of P. aeruginosa and the corresponding CFU (determination coefficient R2 = 0.921, correlation coefficient r = 0.9621, P = 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Correlation of the bacterial luminescence intensity of infected ex vivo rabbit corneas to the corresponding colony-forming units (CFU). Bacterial luminescence intensity is presented in relative light units (RLU).

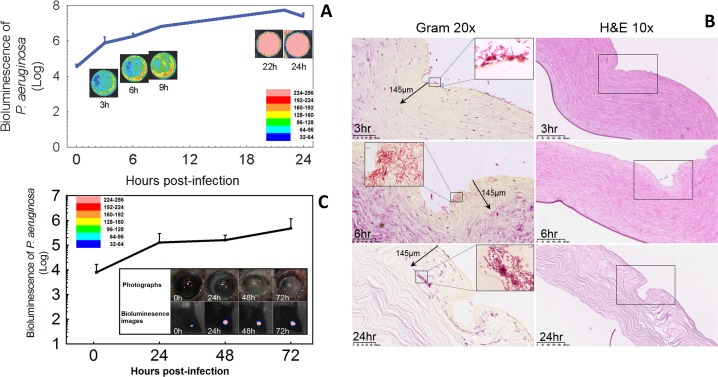

P. aeruginosa Keratitis Fully Developed in Both the Ex Vivo Rabbit Model and the In Vivo Mouse Model

To characterize the development of P. aeruginosa infection in the cornea, the bacterial luminescence was measured for up to 24 hours in the ex vivo rabbit model and up to 72 hours in the in vivo mouse model. In the ex vivo rabbit corneas, the mean bacterial luminescence increased steadily until approximately 9 hours, then remained relatively stable (Fig. 2A, solid line; n = 6). This result was qualitatively apparent from the bacterial luminescence images of a single cornea followed over the same time period.

Figure 2.

Ex vivo rabbit model and in vivo mouse model of P. aeruginosa keratitis. (A) Time course for the bacterial luminescence intensity of ex vivo rabbit eyes infected with 2 × 106 CFU of P. aeruginosa (solid line; n = 6). Successive bacterial luminescence images are shown from a representative infected ex vivo rabbit eye. The pseudo-color scale bar indicates the bioluminescence intensity value of a single pixel in the bioluminescence images. (B) Gram-stained (×20) and H&E-stained histologic sections (×10) of representative ex vivo rabbit eyes infected with 2 × 106 CFU of P. aeruginosa and sampled at 3, 6, and 24 hours after bacterial inoculation. The Gram stain demonstrated the presence of P. aeruginosa in the corneal tissue, with bacteria invaded deeper into the corneal tissue over this time period. The areas in the depicted boxes in ×10 H&E images are shown in ×20 Gram images. The areas in the depicted boxes in ×20 Gram images are illustrated in the insets of ×100 oil lens images. (C) Time course for the bacterial luminescence intensity of in vivo mouse eyes infected with 5 × 105 CFU of P. aeruginosa (solid line; n = 6). Bars: standard deviation. The inset shows the bacterial luminescence images and photographs taken at 0, 24, 36, and 72 hours post inoculation from a representative infected in vivo mouse eye. The pseudo-color scale bar indicates the bioluminescence intensity value of a single pixel in the bioluminescence images.

To characterize the distribution of P. aeruginosa in the rabbit cornea, histology with Gram and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E staining) was performed at 3, 6, and 24 hours post inoculation. At 3 hours post inoculation, P. aeruginosa was primarily located on the surface of corneal tissue. However, the bacteria rapidly proliferated into the stroma and destroyed the structure of cornea at 24 hours post inoculation, due to the lack of an immune response in this ex vivo model (Fig. 2B).

Similarly, after inoculating bacteria onto the scratched in vivo corneas of mice, a 24-hour period of more rapid increase in bacterial luminescence was followed by a more stable level of infection that lasted at least 72 hours. These changes were characterized by both quantitative bioluminescence imaging (Fig. 2C, solid line; n = 6) and photography (Fig. 2C, inset). The photographs of a representative infected mouse eye showed an increased opacity of the mouse cornea with the time post inoculation.

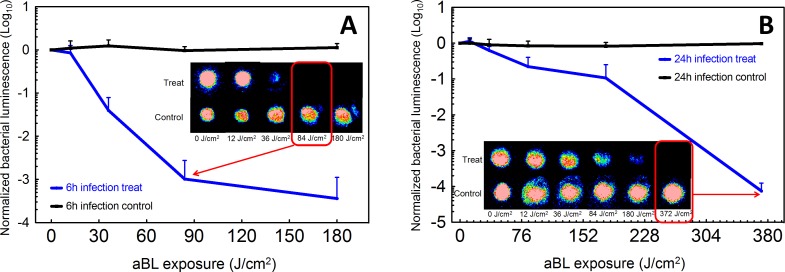

aBL Effectively and Rapidly Reduced P. aeruginosa Burden in the Infected Ex Vivo Rabbit Corneas

Infected rabbit corneas were treated at either 6 or 24 hours post inoculation to investigate the effectiveness of aBL therapy for early-stage or fully established infection. When aBL was delivered at 6 hours post inoculation, the bacterial luminescence decreased with increasing aBL exposure and an approximately 3-log10 inactivation was achieved, compared to untreated control, by exposure to 84 J/cm2 aBL (arrow in Fig. 3A; 14 minutes irradiation). In contrast, when aBL was delivered at 24 hours post inoculation, exposure to 84 J/cm2 aBL elicited less than 1-log10 inactivation (Fig. 3B). Exposure to 304 J/cm2 aBL (∼50 minutes irradiation) was required to achieve approximately 3-log10 inactivation. No bacterial regrowth was observed in any rabbit cornea after aBL exposure.

Figure 3.

Influence of radiant exposure on aBL therapy for keratitis in the ex vivo rabbit model. (A) aBL (180 J/cm2) delivered at 6 hours after inoculation with 2 × 106 CFU of P. aeruginosa (solid line; n = 6). Bars: standard deviation. Bacterial luminescence images of the infected rabbit eyes were taken when 0, 12, 36, 84, and 180 J/cm2 aBL had been delivered (irradiance = 100 mW/cm2) and at the same times in untreated controls. The bacterial luminescence images of representative infected rabbit eyes, treated with aBL or not treated, are shown. The pseudo-color scale bar indicates the bioluminescence intensity value of a single pixel in the bioluminescence images. (B) aBL (372 J/cm2) delivered at 24 hours after inoculation with 2 × 106 CFU of P. aeruginosa (solid line; n = 6). Bars: standard deviation. The bacterial luminescence images were taken when 0, 12, 36, 84, 180, and 372 J/cm2 aBL had been delivered to the infected rabbit eyes (irradiance = 100 mW/cm2) and at the same times in untreated controls. The bacterial luminescence images of representative infected rabbit eyes treated with aBL (372 J/cm2) or not treated are shown. The pseudo-color scale bar indicates the bioluminescence intensity value of a single pixel in the bioluminescence images.

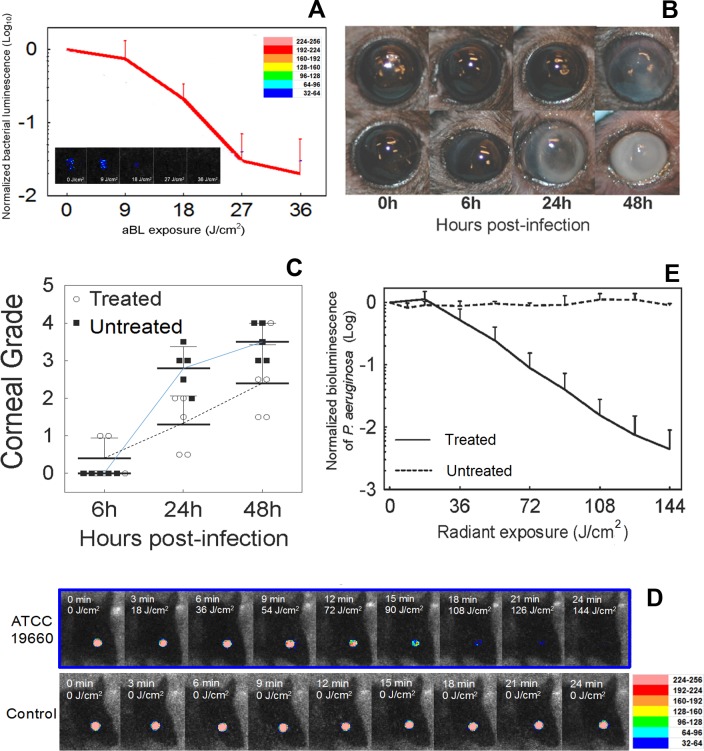

aBL Effectively and Rapidly Reduced P. aeruginosa Burden in Infected Mouse Corneas In Vivo

When aBL was delivered at 6 hours post inoculation, an increase in aBL exposure decreased the bacteria level in in vivo mouse corneas, and an approximately 2.0-log10 inactivation of P. aeruginosa was achieved when an exposure of 36 J/cm2 aBL was delivered (Fig. 4A; 6 minutes irradiation). In contrast, in the untreated mice, bacterial luminescence remained almost unchanged during the equivalent period of time (data not shown). Corneal pathology, as shown in Figure 4B, was scored at 6, 24, and 48 hours after bacterial inoculation, respectively, for both aBL-treated and untreated mice.23 It was observed that the eyes of aBL-treated mice had significantly lower mean corneal pathology scores as compared to the eyes of untreated mice (P = 0.0048, Fig. 4C). In addition, the analysis of the interaction between “aBL treatment” and “time post infection” shows that the effect of aBL treatment increased with the time post infection.

Figure 4.

Influence of radiant exposure on aBL therapy for keratitis in the in vivo mouse model. (A) Influence of radiant exposure of aBL on the bacterial luminescence intensity of mouse eyes infected with 5 × 105 P. aeruginosa and treated with 36 J/cm2 aBL at 6 hours post inoculation (n = 6). The inset shows the bacterial luminescence images from a representative mouse eye infected with 5 × 105 CFU of P. aeruginosa and treated with 36 J/cm2 aBL at 6 hours post inoculation. Bacterial luminescence images were taken when 0, 9, 18, 27, and 36 J/cm2 aBL had been delivered (irradiance = 100 mW/cm2). The pseudo-color scale bar indicates the bioluminescence intensity value of a single pixel in the bioluminescence images. (B) Photographs of two representative mouse eyes infected with 5 × 105 CFU of P. aeruginosa, treated with aBL (36 J/cm2) at 6 hours post infection (top row) or not treated (bottom row), indicating less opacity and damage in the aBL-treated mouse eye than in the untreated one. (C) Corneal pathology scores of the infected mouse eyes treated with 36 J/cm2 aBL at 6 hours post infection (n = 6) or not treated (n = 6), showing the higher mean corneal pathology scores of the untreated mouse eyes than the aBL-treated mouse eyes (P = 0.0048). In addition, the analysis of the interaction between aBL treatment and time post infection shows that the effect of aBL treatment increased with the time post infection. Data were analyzed using the general linear model. (D) The bacterial luminescence images of representative mouse eyes infected with 5 × 105 CFU of P. aeruginosa, treated with 144 J/cm2 aBL 24 hours later or left untreated. The pseudo-color scale bar indicates the bioluminescence intensity value of a single pixel in the bioluminescence images. (E) Influence of radiant exposure of aBL on the bacterial luminescence intensity of the mouse eyes infected with 5 × 105 P. aeruginosa, treated with 144 J/cm2 aBL at 24 hours post inoculation (n = 6), or left untreated (n = 6). Bars: standard deviation. Bacterial luminescence images were taken when 0, 18, 36, 54, 72, 90, 108, 126, and 144 J/cm2 aBL had been delivered (irradiance = 100 mW/cm2).

When aBL was delivered at 24 hours after P. aeruginosa inoculation, the bacterial luminescence was completely eradicated after an exposure of 144 J/cm2 aBL (Fig. 4D). The aBL killing curve of P. aeruginosa shows that a >2.5-log10 inactivation was achieved when an exposure of 144 J/cm2 aBL was delivered (Fig. 4E; 24 minutes irradiation), compared to untreated control.

However, recurrence of infection was observed in the mice treated with aBL at both 6 and 24 hours post inoculation after aBL exposure. The recurrent infection was more severe in mice treated at 24 hours post inoculation than at 6 hours post inoculation.

Toxicity of aBL to the Retina is Largely Dependent on aBL Transmission of the Cornea

Retinal safety is a very important concern for developing aBL as a treatment of keratitis since aBL, in sufficient amount, is highly toxic to the retina.25 Antimicrobial blue light that is not absorbed by the cornea or lens and is not blocked by the iris is transmitted through the pupil and reaches the retina. The wavelengths in aBL are absorbed by the chromophores in the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (e.g., proteins in photoreceptor cells, flavin proteins, heme proteins, melanosomes), and subsequently may produce both photothermal and photochemical damage.25

Using the formula described by Delori et al.,26 we calculated the aBL exposures to reach the retina with the aBL treatment parameters that reduced the bacterial luminescence in the ex vivo rabbit model by approximately 3-log10 (84 J/cm2 for 6 hours post inoculation and 304 J/cm2 for 24 hours post inoculation; see Fig. 3). The initial calculation assumed that the cornea was clear (100% transmission), and subsequent calculations assumed partial cloudiness that decreased the aBL transmission by 50% and 90%. The obtained aBL exposures to reach the retina were compared to the safety thresholds for photothermal and photochemical damage previously established by experimental studies.19 The retinal aBL exposure was calculated for corneal irradiance = 100 mW/cm2 and pupil diameter = 2 mm, and a 10-mm retinal image diameter was assumed. For a clear cornea (100% transmission), the retinal aBL exposure exceeds the retinal safety threshold (i.e., is unsafe) by factors of 1.4× and 5.1× for 84 and 304 J/cm2 aBL, respectively. For a cloudy cornea that blocks 50% of the aBL, 84 J/cm2 aBL delivered to the cornea is below the retina safety threshold by a factor of 1.4 (i.e., 1/1.4 = 0.71-fold of the retina safety threshold), but 304 J/cm2 is above the threshold by a factor of 2.5×. If a very cloudy cornea only transmits 10% of the aBL, 84 and 304 J/cm2 aBL are below the limit by factors of 7.1× and 2.0×, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we developed an ex vivo rabbit model and an in vivo mouse model of infectious keratitis by using a bioluminescent strain of P. aeruginosa and found a good linear correlation between the bacterial luminescence and the corresponding bacterial CFU in the infected corneas. Our results demonstrated that a single exposure of aBL rapidly and significantly reduced bacterial burden in both the ex vivo and in vivo models. The infections treated at 24 hours post inoculation were more resistant to aBL than they were at 6 hours post inoculation. The possible reason is that, at 24 hours post inoculation, infections had fully established and bacteria existed predominantly as biofilms.27 The biofilm matrix could block aBL and render bacterial cells less susceptible to aBL. Other investigators reported the effectiveness of aBL (420 nm) against bacterial biofilms.28 Additionally, when infections had fully established, bacteria might have proliferated into the deeper layers of the corneal tissue (as shown in Fig. 2B), where the aBL transmission was further attenuated. In a previous study of aBL therapy for P. aeruginosa burn infection in mice, we observed that, when aBL was applied 30 minutes post inoculation, an average 3.5-log10 inactivation of P. aeruginosa in mouse burns was achieved when an exposure of 55.8 J/cm2 aBL had been delivered.

Recurrence of infection was observed in mice (but not in the rabbit corneas) after a single exposure of aBL. One possible reason of infection recurrence is that bacteria in the infected corneas were not completely eradicated after aBL exposure even when bacterial luminescence was eliminated due to the sensitivity limitation of the bioluminescence imaging system (>102 CFU). Another possible reason is that part of the corneal area was shielded by eyelids and this prevented aBL from irradiating this area, rendering the shielded area actually untreated. The bacteria surviving from the aBL exposure subsequently induced recurrence of infection. This hypothesis was supported by the results obtained from the study using the ex vivo rabbit corneas. In the ex vivo study, the whole area of excised rabbit corneas was exposed to aBL and no bacterial regrowth was found in any aBL-treated cornea after aBL exposure. Several approaches could be considered to improve the effectiveness of aBL therapy, such as repeated aBL treatments (two or three times) and combined therapy using aBL and subtherapeutic dose of antibiotics (antimicrobial eye drops), which can reach the corneal area under the eyelids after topical application.

Corneal safety is a very important concern for developing aBL as a therapeutic for keratitis. In our previous in vitro studies, we demonstrated that bacteria (P. aeruginosa ATCC 19660) were much more resistant to 415-nm aBL than were human keratinocytes. When 109.9 J/cm2 aBL had been delivered, an approximately 7.64-log10 CFU inactivation of P. aeruginosa was achieved. In contrast, under the same aBL irradiation condition, only a 0.16-log10 loss of viability of human keratinocytes was observed.29 Other investigators reported that when 100 J/cm2 blue light at 410 nm had been delivered, the viability of corneal epithelial cells in vitro decreased by approximately 1-log10.30 Further study on the potential toxicity of aBL on the cornea (i.e., corneal epithelial, endothelial, and keratocyte cells) is needed.

There are also limitations of the in vivo mouse model used in the present study since mouse eyes differ substantially from human eyes. The human cornea is approximately 11 mm in diameter, whereas mouse corneas have a 2.2- to 3.5-mm diameter.31,32 The axial length of human eyes is approximately eight times longer than that of mouse eyes, and the corneal thickness is greater for humans than for mice. The arrangement of corneal collagen and the properties of corneal epithelial cells also differ between mice and humans,32,33 which could produce alternate reactions of the cornea to invading pathogens. Descemet's and Bowman's membranes are substantially thinner in mice than in humans,32,34 and mouse corneas have a higher ratio of corneal epithelial cells to stroma than humans and more cell layers in the corneal epithelium.31,32 All of these anatomic differences have an effect on aBL delivery, bacterial adherence and possible invasion, susceptibility to bacterial enzymes and other virulence factors, and availability of host defense molecules in the tear film. As a result, the effectiveness of aBL against keratitis needs to be further investigated using large in vivo animal models, for example, a rabbit or dog model, which are more similar to humans in ocular anatomy.

In addition, aBL potentially can produce both photothermal and photochemical damage in the retina. According to the ANSI 136.1, we estimated the aBL toxicity to the retina under different aBL transmission of the corneal conditions. The calculations indicated that the aBL toxicity to the retina is largely dependent on the aBL transmission of the cornea. The corneal opacity of infected corneas means that more light would be blocked by infected corneas than by intact corneas. Apparently, to validate the results obtained from the theoretical calculation, further experimental study using animal models and clinical study are essential.

Overall, our study suggests that aBL is a potential alternative or adjunctive approach for the treatment of infectious keratitis, in particular those caused by drug-resistant pathogens. Successful treatment of keratitis using aBL requires optimal timing, careful regulation of aBL exposure, and adequate concomitant antibacterial medication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hang Lee, PhD, from the Harvard Catalyst Biostatistical Consulting Program for his generous help with statistical analysis.

Supported in part by the Smith Infectious Diseases Foundation (Research Grant Award to TD), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-16-1-0479 to TD), and the National Institutes of Health (1R21AI109172 and 1R01AI123312 to TD).

Disclosure: H. Zhu, None; I.E. Kochevar, None; I. Behlau, None; J. Zhao, None; F. Wang, None; Y. Wang, None; X. Sun, None; M.R. Hamblin, None; T. Dai, None

References

- 1. Collier SA,, Gronostaj MP,, MacGurn AK,, et al. Estimated burden of keratitis--United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 63: 1027–1030. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green M,, Apel A,, Stapleton F. Risk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitis. Cornea. 2008; 27: 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fernandes M,, Vira D,, Medikonda R,, Kumar N. Extensively and pan-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis: clinical features, risk factors, and outcome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016; 254: 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vazirani J,, Wurity S,, Ali MH. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis: risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2015; 122: 2110–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Willcox MD. Review of resistance of ocular isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and staphylococci from keratitis to ciprofloxacin, gentamicin and cephalosporins. Clin Exp Optom. 2011; 94: 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang VS,, Dhaliwal DK,, Raju L,, Kowalski RP. Antibiotic resistance in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus keratitis: a 20-year review. Cornea. 2015; 34: 698–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mah FS,, Davidson R,, Holland EJ,, et al. Current knowledge about and recommendations for ocular methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014; 40: 1894–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hong J,, Chen J,, Sun X,, et al. Paediatric bacterial keratitis cases in Shanghai: microbiological profile, antibiotic susceptibility and visual outcomes. Eye (Lond). 2012; 26: 1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jhanji V,, Moorthy S,, Vajpayee RB. Microbial keratitis in patients with down syndrome: a retrospective study. Cornea. 2009; 28: 163–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chhablani J. Fungal endophthalmitis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011; 9: 1191–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Edelstein SL,, Akduman L,, Durham BH,, Fothergill AW,, Hsu HY. Resistant Fusarium keratitis progressing to endophthalmitis. Eye Contact Lens. 2012; 38: 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McDonald EM,, Ram FS,, Patel DV,, McGhee CN. Topical antibiotics for the management of bacterial keratitis: an evidence-based review of high quality randomised controlled trials. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014; 98: 1470–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gokhale NS. Medical management approach to infectious keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008; 56: 215–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goldstein MH,, Kowalski RP,, Gordon YJ. Emerging fluoroquinolone resistance in bacterial keratitis: a 5-year review. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106: 1313–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dai T,, Gupta A,, Murray CK,, Vrahas MS,, Tegos GP,, Hamblin MR. Blue light for infectious diseases: Propionibacterium acnes, Helicobacter pylori, and beyond? Drug Resist Updat. 2012; 15: 223–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Enwemeka CS. Antimicrobial blue light: an emerging alternative to antibiotics. Photomed Laser Surg. 2013; 31: 509–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maclean M,, MacGregor SJ,, Anderson JG,, Woolsey G. Inactivation of bacterial pathogens following exposure to light from a 405-nanometer light-emitting diode array. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009; 75: 1932–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Y,, Zhu Y,, Gupta A,, et al. Antimicrobial blue light therapy for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection in a mouse burn model: implications for prophylaxis and treatment of combat-related wound infections. J Infect Dis. 2014; 209: 1963–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laser Institute of America. American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers. Orlando, Florida: Laser Institute of America; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karmakar M,, Sun Y,, Hise AG,, Rietsch A,, Pearlman E. Cutting edge: IL-1beta processing during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection is mediated by neutrophil serine proteases and is independent of NLRC4 and caspase-1. J Immunol. 2012; 189: 4231–4235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rocchetta HL,, Boylan CJ,, Foley JW,, et al. Validation of a noninvasive, real-time imaging technology using bioluminescent Escherichia coli in the neutropenic mouse thigh model of infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001; 45: 129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hamblin MR,, Zahra T,, Contag CH,, McManus AT,, Hasan T. Optical monitoring and treatment of potentially lethal wound infections in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2003; 187: 1717–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zaidi TS,, Zaidi T,, Pier GB. Role of neutrophils, MyD88-mediated neutrophil recruitment, and complement in antibody-mediated defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 2085–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jett BD,, Hatter KL,, Huycke MM,, Gilmore MS. Simplified agar plate method for quantifying viable bacteria. Biotechniques. 1997; 23: 648–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Youssef PN,, Sheibani N,, Albert DM. Retinal light toxicity. Eye (Lond). 2011; 25: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Delori FC,, Webb RH,, Sliney DH. Maximum permissible exposures for ocular safety (ANSI 2000), with emphasis on ophthalmic devices. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2007; 24: 1250–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Romling U,, Balsalobre C. Biofilm infections, their resilience to therapy and innovative treatment strategies. J Intern Med. 2012; 272: 541–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Sousa DL,, Lima RA,, Zanin IC,, Klein MI,, Janal MN,, Duarte S. Effect of twice-daily blue light treatment on matrix-rich biofilm development. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0131941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dai T,, Gupta A,, Huang YY,, et al. Blue light rescues mice from potentially fatal Pseudomonas aeruginosa burn infection: efficacy, safety, and mechanism of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013; 57: 1238–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee JB,, Kim SH,, Lee SC,, et al. Blue light-induced oxidative stress in human corneal epithelial cells: protective effects of ethanol extracts of various medicinal plant mixtures. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 4119–4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Henriksson JT,, McDermott AM,, Bergmanson JP. Dimensions and morphology of the cornea in three strains of mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 3648–3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marquart ME. Animal models of bacterial keratitis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011; 2011: 680642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jester JV,, Budge A,, Fisher S,, Huang J. Corneal keratocytes: phenotypic and species differences in abundant protein expression and in vitro light-scattering. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 2369–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hayashi S,, Osawa T,, Tohyama K. Comparative observations on corneas, with special reference to Bowman's layer and Descemet's membrane in mammals and amphibians. J Morphol. 2002; 254: 247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]