Abstract

Purpose

Survival in older adults with cancer varies given differences in functional status, comorbidities, and nutrition. Prediction of factors associated with mortality, especially in hospitalized patients, allows physicians to better inform their patients about prognosis during treatment decisions. Our objective was to analyze factors associated with survival in older adults with cancer following hospitalization.

Methods

Through a retrospective cohort study, we reviewed 803 patients who were admitted to Barnes-Jewish Hospital’s Oncology Acute Care of Elders (OACE) unit from 2000–2008. Data collected included Geriatric Assessments from OACE screening questionnaires as well as demographic and medical history data from chart review. The primary end point was time from index admission to death. Cox proportional hazard modeling was performed.

Results

The median age was 72.5 years old. Geriatric syndromes and functional impairment were common. Half of the patients (50.4%) were dependent in one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) and 74% were dependent in at least one instrumental activity of daily living (IADLs). On multivariate analysis, the following factors were significantly associated with worse overall survival: male gender; a total score <20 on Lawton’s IADL assessment; reason for admission being cardiac, pulmonary, neurologic, inadequate pain control or failure to thrive; cancer type being thoracic, hepatobiliary, or genitourinary; readmission within 30 days; receiving cancer treatment with palliative rather than curative intent; cognitive impairment; and discharge with hospice services.

Conclusions

In older adults with cancer, certain geriatric parameters are associated with shorter survival after hospitalization. Assessment of functional status, necessity for readmission, and cognitive impairment may provide prognostic information so that oncologists and their patients make more informed, individualized decisions.

Keywords: Geriatric assessment, cancer, mortality, prediction, elderly, aging

Introduction

As life expectancy increases, the number of older adults with cancer continues to rise [1]. While approximately 60% of cancer diagnoses occur in patients older than 65 years [2], older adults are underrepresented in clinical trials, making evidence-based management challenging [3,4]. Although age is sometimes a factor in treatment options and overall outcomes [5], this population tends to be quite heterogeneous; prognosis in older adults with cancer is variable given differences in functional status, comorbidities, nutrition, and other individual factors.

Given this immense variability, physicians experience difficulty in predicting which patients are at risk for shorter survival. The use of continued intensive treatment at end of life and low rates of hospice enrollment may reflect, in part, this challenge in determining an individual older patient’s prognosis. Several studies have established the substantial number of patients receiving chemotherapy near end of life [6,7]. One study demonstrated that 15.7% of patients were still receiving chemotherapy within 2 weeks of death. Although palliative chemotherapy is sometimes given for symptomatic improvement, a recent study established that patients with good performance status who received chemotherapy at end-of-life had poorer quality of life than those who did not [8]. Despite the known advantages in palliative care and hospice on quality-of-life, enrollment is low and occurs close to death [9]. The median length of stay after hospice enrollment is about 18 days with 15% having a length of stay fewer than 3 days [10].

Baseline geriatric assessment, evaluations of comorbidities and medication use, and nutritional status have all been proposed to help clinicians predict morbidity and mortality in older cancer patients. The International Society of Geriatric Oncology recommends a comprehensive geriatric assessment in treating older cancer patients in order to possibly improve survival [11]. However, research on which assessments are most useful in predicting outcomes is limited. In a recent review regarding comprehensive geriatric assessment in cancer patients [12], relationship between CGA and mortality was evaluated in nine studies [13–17,5,18–21]. Although these provide important preliminary data, most of this data is established in outpatient settings [22].

Because a hospitalization may represent a sentinel event in the life of older adults with cancer and geriatric assessment is predictive of adverse outcomes, our goal in this study was to identify factors associated with shorter survival following hospitalization to allow clinicians, patients, and their families to make more informed decisions.

Methods

The study was approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office. We retrospectively reviewed all patients admitted to the Barnes-Jewish Hospital’s Oncology Acute Care for Elders (OACE) unit from 2000–2008 who underwent geriatric assessment. Patients hospitalized in the OACE unit were managed by an interdisciplinary team, which was formed to improve outcomes in older patients. We included patients who had active cancer or who had received treatment for cancer in the last one year prior to admission. In patients who were admitted more than one time during the study period, only the initial hospitalization was analyzed. Patients who died during hospitalization were excluded.

Details about the assessments have been published previously [23]. Briefly, geriatric assessment data was obtained from OACE screening questionnaires that were routinely conducted on patients admitted to this unit. The surveys, performed within 72 hours of admission, included the Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living Scale[24], the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale [25], the Clock Completion Test [26], and the Short Blessed Test [27]. Based on previously established data, patients with a score of 4 or greater on the Clock Completion Test or 9 or greater on the Short Blessed Test were considered to have cognitive impairment.

Chart review was conducted to obtain demographic and medical data including: race; cancer type; albumin; treatment intent (curative or palliative); reason for admission; number of medications on admission and discharge; presence of skin breakdown or wounds on admission; number of falls; formal inpatient physical therapy or occupational therapy consultation; requirement for restraints or sitter; and diagnosis of dementia. Review of admission and progress notes, pathology reports, and radiographic data was performed by the study team and supervised by a board-certified medical oncologist. The Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 was used to evaluate information about medical comorbidities and was obtained from the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Cancer Registry [28]. The reason for admission (RFA) was determined by review of patient’s chief complaint and admitting physician’s assessment and plan. The admitting diagnosis was then grouped into broader categories either by disease system or similar reasons.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequencies, and percentage) were used to analyze baseline characteristics. The primary endpoint was overall survival, defined as the time from index admission to death, censored at last follow up. Cox proportional-hazards model was used to evaluate the relationships between baseline characteristics and overall survival. Variables in Table 1 were selected a priori and examined by univariate analysis. Variables with a probability value of less than 0.20 were included in multivariate analysis. Some variables were excluded from the multivariate model due to excessive missing data. Overall, C-index and 95% CI were calculated as a measure of discrimination of model validation. All statistical tests were two-sided using a level of significance of 0.05. SAS version 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, NC) was used to perform all statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N=803)

| Baseline Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | |

| 65–70 | 290 (35.1) |

| 70–80 | 376 (46.8) |

| 80+ | 137 (17.1) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 387 (48.2) |

| Male | 416 (51.8) |

| Race | |

| White | 618 (77.0) |

| Black | 170 (21.2) |

| Other | 15 (1.9) |

| Cancer Type | |

| Thoracic | 266 (33.1) |

| GI | 134 (16.7) |

| Breast | 51 (6.4) |

| Hepatobiliary | 85 (10.6) |

| Genitourinary | 63 (7.9) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 151 (18.8) |

| Other | 53 (6.6) |

| Cancer stage | |

| Stage I | 19 (2.4) |

| Stage II | 32 (4.0) |

| Stage III or limited stage small cell | 116 (14.5) |

| Stage IV, metastatic oextensive stage small cell | 453 (56.4) |

| Not applicable or Unknown | 183 (22.7) |

| Admitted from | |

| Home or Domiciliary | 731 (91.0) |

| Nursing Home | 9 (1.1) |

| Skilled Nursing Home | 16 (2.0) |

| Assisted Living/Independent living | 8 (1.0) |

| Outside Hospital | 35 (4.4) |

| Acute care rehabilitation | 4 (0.5) |

| Discharge Disposition | |

| Home or Domiciliary | 659 (82.1) |

| Nursing Home | 7 (0.9) |

| Skilled nursing | 110 (13.7) |

| Assisted Living/Independent Living | 4 (0.50) |

| Acute care rehab | 16 (2.0) |

| Transfer to another hospital | 7 (0.9) |

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 803 patients were evaluated in the study after patients who died during hospitalization were excluded. Baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age of patients was 72.5 years old with an almost even distribution of male and females. Most patients were white (77.0%), admitted from home (91.0%), and discharged back to home (82.1%).

Geriatric syndromes were common. The median number of medications on admission was six. Functional impairments were common: 50.4% of patients required assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) and 74.0% required assistance with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) at the time of hospitalization. Fewer than one-in-five (18.5%) had no comorbidities, while 47% had mild comorbidities, 23.5% had moderate comorbidities, and 10.6% had severe comorbidities. Cognitive impairment was present in 43% of patients.

Survival Analysis

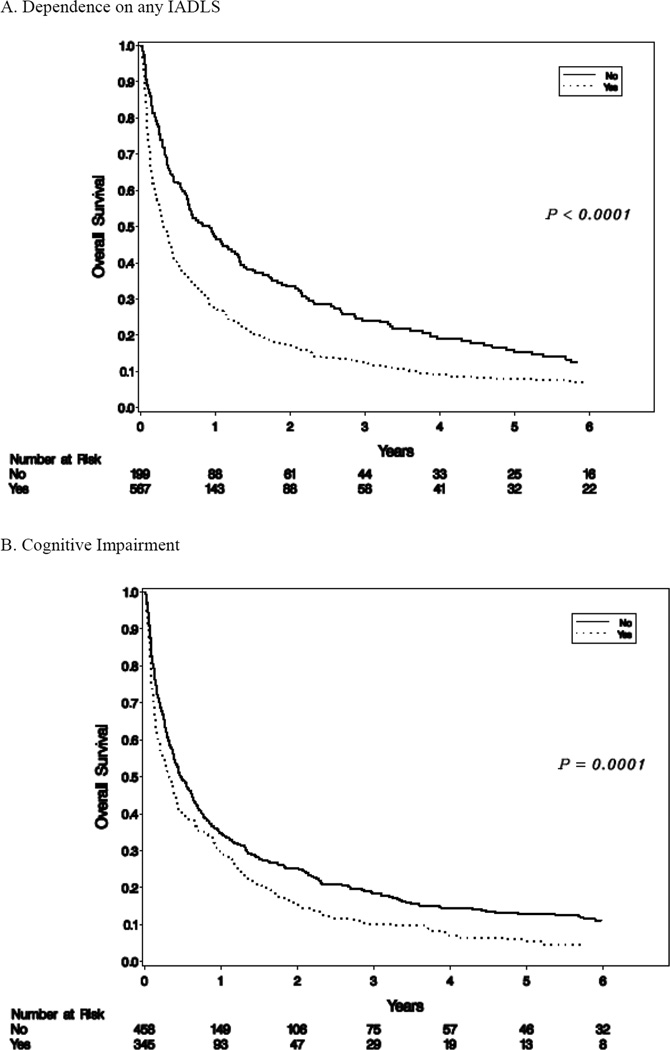

The median overall survival was 4.9 months. The proportions of patients alive at 6-months and 1-year were 45.5% and 32.7% respectively. Univariate analysis was initially performed on all factors that were potentially associated with survival (Table 2). The following variables were significantly associated with shorter survival: male gender; albumin<3.5 mg/dL; taking more than seven medications on admission; any ADL dependence (Katz scale <17); any IADL dependence (Lawton scale<20) (Figure 1); disposition to hospice; having skin breakdown on admission; requiring a one-to-one sitter during hospitalization; requiring readmission within 30 days; diagnosis of cognitive impairment (Figure 1); and palliative rather than curative intent cancer treatment. Higher BMI showed a marginally significant association with longer survival. Reason for admission, cancer type, and stage IV cancer were associated with overall survival but comorbidities were not.

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model Examining Predictors of Overall Survival

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI), | p-value | |

| Male Sex | 1.17 (1.01–1.36) | 0.04 | 1.23 (1.03–1.46) | 0.02 |

| BMI | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.06 | 0.98 (0.97–1.00) | 0.06 |

| Albumin <3.5 ml/dL* | 1.45 (1.09–1.92) | 0.01 | ||

| Dependence in Activities of Daily Living (Katz scale <17/18) | 1.43 (1.29–1.76) | <0.0001 | ||

| Dependence in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (Lawton scale <20/24) |

1.64 (1.41–1.91) | <0.0001 | 1.34 (1.12–1.60) | 0.002 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1.34 (1.15–1.56) | <0.0001 | 1.24 (1.03–1.48) | 0.02 |

| Requirement of a sitter or restraints | 1.77 (1.15–2.72) | 0.01 | ||

| Number of medications ≥ 7 | 1.18 (1.02–1.38) | 0.03 | ||

| Skin breakdown (on admission or during hospitalization)* | 1.64 (1.26–2.12) | 0.0002 | ||

| Reason for admissiona | 1.49 (1.29–1.74) | <0.0001 | 1.30 (1.09–1.552) | 0.003 |

| Readmission within 30-days | 1.58 (1.34–1.85) | 1.50 (1.24–1.80) | <0.0001 | |

| Discharge with hospice services | 4.59 (3.43–6.13) | <0.0001 | 3.54 (2.54–4.94) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer typeb | 1.76 (1.51–2.06) | <0.0001 | 1.65 (1.38–1.99) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer Stage IV | 1.99 (1.63–2.43) | <0.0001 | ||

| Cancer treatment intent (palliative vs. curative) | 1.94 (1.6–2.34) | <0.0001 | 1.89 (1.52–2.34) | <0.0001 |

|

Model C-index 0.66 (95% CI 0.58–0.72) |

||||

Missing data prevented variable from moving forward in multivariate model.

Cardiac/pulmonary, neurologic, pain, failure to thrive vs. gastrointestinal/genitourinary, abnormal labs, bleeding or infection

Thoracic, hepatobiliary, genitourinary, other vs. gastrointestinal, breast or hematologic malignancies

Figure 1.

Overall Survival

A multivariate analysis was then established to determine which variables remained as independent prognostic factors for overall survival (Table 2). Male gender and cancer type (thoracic, hepatobilliary, and genitourinary cancers) were significantly associated with greater mortality. Certain reasons for admission including cardiac, pulmonary, and neurologic causes, pain control, and failure to thrive were significantly associated with shorter survival compared with those for gastrointestinal diagnoses, abnormal labs, bleeding, or infection. A total score <20 on Lawton’s assessment, readmission within 30 days, palliative intent treatment, cognitive impairment and discharge with hospice services were significantly associated with worse overall survival. The overall c-index for the final multivariate model is 0.66 (95% Confidence Intervals 0.58–0.72).

Discussion

Older adults with cancer represent a unique population as their ability to tolerate treatment and their overall prognosis is heterogeneous. Previous studies have demonstrated functional status, cognitive impairment, and presence of comorbidities or depression to be predictive of mortality in the general geriatric population [29,30]. However, studies regarding older adults with cancer are not as well-established. A hospitalization may be a sentinel event in the life of an older adult with cancer, triggering appraisal or re-appraisal of an individual’s goals of care. In this retrospective cohort study, we identified demographic, clinical and geriatric assessment factors that are associated with mortality in older patients with cancer.

Dependence in ADLs and IADLs were significantly associated with death in older cancer patients following hospitalization. Maione et al. established a similar finding showing that functional status by IADL scores was predictive of survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy [20]. In contrast, a previous prospective study found that dependence in ADLs and IADLs was not associated with early death in outpatients undergoing first-line chemotherapy [13]. Our study suggests that dependence in ADLs and IADLs in hospitalized older adults with cancer is associated with poorer prognosis.

Hospital readmission within 30 days was related to increased mortality in our study. Readmission related to cancer is common and occurs for new diagnoses, symptoms from cancer progression, and complications of procedures [31,32]. We recently identified dependence on IADLs, use of potentially inappropriate medications, and higher risk reasons for index admission to be associated with readmission [33]. Readmission to the hospital provides an opportunity for clinicians to reevaluate prognosis and goals of care.

Cognitive decline has been shown to decrease the probability that a patient will complete chemotherapy [34]. Our findings showed that cognitive impairment, as defined as an abnormal Short Blessed test or Clock Drawing test, or by the diagnosis of dementia, was also associated with increased mortality. Given that these assessments only take a few minutes and are easy to administer, completion of these tests during hospitalization may help clinicians better evaluate prognosis. In this study, we are unable to further explore whether abnormal cognitive screening tests are related to underlying cognitive impairment or delirium.

A higher comorbidity index score was not associated with increased mortality in our study. This finding conflicts with some previous studies that have found a significant difference [35–37]. Given the very short overall survival (median 4.9 months), the effect of comorbidity may have been masked by overall poor prognosis of individuals in the cohort. In fact, Read et al. demonstrated that comorbidity was more prognostic in less aggressive cancers that have better overall survival [35]. The assessments used to determine comorbidity in previous studies differed from those used in the current study, which may also influence the differences.

The fact that discharge with hospice services was associated with earlier death is not surprising, indicating that clinicians, patients, and their families identified the patient’s incipient decline. However, that a number of other variables remained predictive after controlling for discharge with hospice services indicates that a significant number of patients who were not discharged with hospice remained at risk of earlier death. This highlights the need to improve our ability to predict which individuals are at greatest risk of death to encourage the initiation of important end-of-life conversations with them.

This study has several limitations. Patients were included with differing cancer diagnoses and stages of disease, which have a major impact on prognosis and survival. However, this inclusion allows physicians to determine other general risk factors for death in addition to known prognosis of different cancer types and makes our findings more generalizable. Retrospective data collection has limitations. For example, certain geriatric assessment factors including assessment of independence in ADLs and IADLs were evaluated by the subjective report of patients and family members. Some clinical data points, including medication use, are limited by collection from the medical record, which may not accurately reflect what a patient is actually prescribed or taking. Furthermore, other factors potentially affecting prognosis including differences in treatment, patient preferences on treatment and disposition, and social support were not accounted for in the available data. Given our study population included hospitalized patients, their acute illness may have affected scores for cognitive tests such as the Short Blessed Test and Clock Drawing Test. Missing data restricted multivariate analysis of certain factors that were significant in the univariate model, such as skin breakdown and albumin; these factors may warrant examination in future studies.

Geriatric assessment is increasingly being recognized as an important tool in the care of older adults with cancer. Several studies have created scales and tools to assess risk of chemotherapy toxicity incorporating geriatric assessment [38,39]. Tools to predict mortality, particularly early mortality, need validation and refinement [40]. Integrating geriatric assessment into their evaluation may help oncologists offer more individualized estimates of prognosis for older adults following a hospitalization. Improved tools to predict mortality may encourage earlier discussions about goals of care, earlier evaluation for hospice, and possibly better quality-of-life for our older cancer patients. Following prospective validation of this model, future intervention studies are needed to evaluate whether prognostic information impacts shared decision-making and quality-of-life in older adults with cancer who are at risk for shorter survival following a hospitalization.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number 1K12CA167540 through the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Grant Number UL1 TR000448 through the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCI, NCATS or NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: We have no financial disclosures. We have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

References

- 1.Ries EMKC, Hankey BF, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review: 1975–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, Trimble EL, Kaplan R, Montello MJ, Housman MG, Escarce JJ. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(7):1383–1389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scher KS, Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2036–2038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter LC, Brand RJ, Counsell SR, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS, Fortinsky RH, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 1-year mortality in older adults after hospitalization. JAMA. 2001;285(23):2987–2994. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anshushaug M, Gynnild MA, Kaasa S, Kvikstad A, Gronberg BH. Characterization of patients receiving palliative chemo- and radiotherapy during end of life at a regional cancer center in Norway. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(3):395–402. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.948061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, Paulk ME, LeBlanc TW, Schneider BJ, Garrido MM, Reid MC, Berlin DA, Adelson KB, Neugut AI, Maciejewski PK. Chemotherapy Use Performance Status, and Quality of Life at the End of Life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(6):778–784. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: NHPCO FY2012 national summary of hospice care. http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/NDS_2012_National_Summary_20131106.pdf.

- 10.O'Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS, Ache K, Casarett DJ. Hospice admissions for cancer in the final days of life: independent predictors and implications for quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(28):3184–3189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei RB, Cohen HJ, Droz JP, Lichtman S, Mor V, Monfardini S, Repetto L, Sorbye L, Topinkova E. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: Recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Crit Rev Oncol Hemat. 2005;55(3):241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caillet P, Laurent M, Bastuji-Garin S, Liuu E, Culine S, Lagrange JL, Canoui-Poitrine F, Paillaud E. Optimal management of elderly cancer patients: usefulness of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1645–1660. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S57849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soubeyran P, Fonck M, Blanc-Bisson C, Blanc JF, Ceccaldi J, Mertens C, Imbert Y, Cany L, Vogt L, Dauba J, Andriamampionona F, Houede N, Floquet A, Chomy F, Brouste V, Ravaud A, Bellera C, Rainfray M. Predictors of early death risk in older patients treated with first-line chemotherapy for cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1829–1834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falandry C, Weber B, Savoye AM, Tinquaut F, Tredan O, Sevin E, Stefani L, Savinelli F, Atlassi M, Salvat J, Pujade-Lauraine E, Freyer G. Development of a geriatric vulnerability score in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer treated with first-line carboplatin: a GINECO prospective trial. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2808–2813. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giantin V, Valentini E, Iasevoli M, Falci C, Siviero P, De Luca E, Maggi S, Martella B, Orru G, Crepaldi G, Monfardini S, Terranova O, Manzato E. Does the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI), based on a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), predict mortality in cancer patients? Results of a prospective observational trial. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(3):208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanesvaran R, Li H, Koo KN, Poon D. Analysis of prognostic factors of comprehensive geriatric assessment and development of a clinical scoring system in elderly Asian patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(27):3620–3627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tougeron D, Di Fiore F, Thureau S, Berbera N, Iwanicki-Caron I, Hamidou H, Paillot B, Michel P. Safety and outcome of definitive chemoradiotherapy in elderly patients with oesophageal cancer. Brit J Cancer. 2008;99(10):1586–1592. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bo M, Cacello E, Ghiggia F, Corsinovi L, Bosco F. Predictive factors of clinical outcome in older surgical patients. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2007;44(3):215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim KI, Park KH, Koo KH, Han HS, Kim CH. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict postoperative morbidity and mortality in elderly patients undergoing elective surgery. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2013;56(3):507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maione P, Perrone F, Gallo C, Manzione L, Piantedosi F, Barbera S, et al. Pretreatment quality of life and functional status assessment significantly predict survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy: a prognostic analysis of the multicenter Italian lung cancer in the elderly study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):6865–6872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramjaun A, Nassif MO, Krotneva S, Huang AR, Meguerditchian AN. Improved targeting of cancer care for older patients: a systematic review of the utility of comprehensive geriatric assessment. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(3):271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamaker ME, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, de Rooij SE, van Munster BC. The value of geriatric assessments in predicting treatment tolerance and all-cause mortality in older patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2012;17(11):1439–1449. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flood KL, Carroll MB, Le CV, Ball L, Esker DA, Carr DB. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an oncology-acute care for elders unit. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(15):2298–2303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of Adl: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson YI, Arfken CL, Birge SJ. Clock completion: an objective screening test for dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(11):1235–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawas C, Karagiozis H, Resau L, Corrada M, Brookmeyer R. Reliability of the Blessed Telephone Information-Memory-Concentration Test. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1995;8(4):238–242. doi: 10.1177/089198879500800408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, Grove L, Spitznagel EL., Jr Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291(20):2441–2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reuben DB, Rubenstein LV, Hirsch SH, Hays RD. Value of functional status as a predictor of mortality: results of a prospective study. Am J Med. 1992;93(6):663–669. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90200-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfson C, Wolfson DB, Asgharian M, M'Lan CE, Ostbye T, Rockwood K, Hogan DB Clinical Progression of Dementia Study G. A reevaluation of the duration of survival after the onset of dementia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(15):1111–1116. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders ND, Nichols SD, Antiporda MA, Johnson K, Walker K, Nilsson R, Graham L, Old M, Klisovic RB, Penza S, Schmidt CR. Examination of unplanned 30-day readmissions to a comprehensive cancer hospital. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):e177–e181. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manzano JG, Gadiraju S, Hiremath A, Lin HY, Farroni J, Halm J. Unplanned 30-Day Readmissions in a General Internal Medicine Hospitalist Service at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(5):410–415. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiang LY, Liu J, Flood KL, Carroll MB, Piccirillo JF, Stark S, Wang A, Wildes TM. Geriatric assessment as predictors of hospital readmission in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6(4):254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aaldriks AA, Maartense E, le Cessie S, Giltay EJ, Verlaan HA, van der Geest LG, Kloosterman-Boele WM, Peters-Dijkshoorn MT, Blansjaar BA, van Schaick HW, Nortier JW. Predictive value of geriatric assessment for patients older than 70 years, treated with chemotherapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;79(2):205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Read WL, Tierney RM, Page NC, Costas I, Govindan R, Spitznagel EL, Piccirillo JF. Differential prognostic impact of comorbidity. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):3099–3103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wedding U, Rohrig B, Klippstein A, Pientka L, Hoffken K. Age, severe comorbidity and functional impairment independently contribute to poor survival in cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133(12):945–950. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagel G, Wedding U, Rohrig B, Katenkamp D. The impact of comorbidity on the survival of postmenopausal women with breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130(11):664–670. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0594-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, Lyman GH, Brown RH, DeFelice J, Levine RM, Lubiner ET, Reyes P, Schreiber FJ, 3rd, Balducci L. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3377–3386. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, Owusu C, Klepin HD, Gross CP, Lichtman SM, Gajra A, Bhatia S, Katheria V, Klapper S, Hansen K, Ramani R, Lachs M, Wong FL, Tew WP. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maas HA, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Olde Rikkert MG, Machteld Wymenga AN. Comprehensive geriatric assessment and its clinical impact in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(15):2161–2169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]