Abstract

A common type of transgression in early childhood involves creating inconvenience, for instance by spilling, playing with breakable objects, or otherwise interfering with people’s ongoing activities. Despite the prevalence of such pragmatic transgressions, little is known about children’s conceptions of norms prohibiting these acts. The present study investigated whether 3-to 5-year-olds (N = 58) see pragmatic norms as distinct from first-order moral (welfare and rights of others), prudential (welfare of agent), and social conventional norms. Children judged all four types of transgressions to be wrong. Justifications for pragmatic transgressions focused on inconvenience to the transgressor, inconvenience to others, or material disorder. Children rated pragmatic and conventional transgressions as less serious than moral and prudential transgressions. Latent Class Analysis provided further support for the conclusion that preschoolers see pragmatic norms as a category distinct from first-order moral, prudential, and social conventional norms.

Keywords: Norms, social judgments, social domains

The social world of young children is pervaded by norms for how to behave, specifying how to interact with objects, with people, and in specific social settings. As children go from infancy and toddlerhood to preschool age, caregivers come to endorse an increasing variety of norms for what their children should and should not do (Gralinski & Kopp, 1993; Smetana, Kochanska, & Chuang, 2000). During this same period, children themselves gradually come to express, justify, and enforce such norms (Nucci & Weber, 1995; Schmidt, Rakoczy, & Tomasello, 2012; Smetana & Braeges, 1990; Smetana et al., 2012; Vaish, Missana, & Tomasello, 2011).

The ability to distinguish between different categories of transgressive acts is an integral part of children’s understanding of norms (Smetana, 2006; Turiel, 1983, in press). Transgressions differ importantly along several dimensions, including who they affect (the transgressor, others, or no one) and whether their consequences are direct (immediate and intrinsic) or indirect (i.e. mediated by other events). Distinguishing between types of transgressions and the corresponding types of norms allow children to coordinate their own, sometimes conflicting, norm-related concerns.

Of particular relevance in early childhood are acts that cause inconvenience, such as spilling (somebody will have to clean up), playing with breakable family property (item will become unusable or someone will have to repair or replace it), or interfering with people’s ongoing activities. We refer to these acts as violations of pragmatic norms and define them as acts with direct, physical consequences that indirectly interfere with the goals and activities of the transgressor or someone else (Dahl & Campos, 2013; Smetana et al., 2000). The interference with ongoing activities is indirect in the sense that it is mediated by a person’s response to the physical consequences, for instance through the act of cleaning up. Although, by one estimate, these pragmatic transgressions constitute about half of all transgressions in the second year of life (Dahl, Campos, & Turiel, 2012), past research has not investigated how children think about pragmatic norms. The present study investigated whether preschoolers see pragmatic transgressions as a category distinct from three other types of transgressions more commonly studied.

One type of action to be contrasted with pragmatic transgressions is that which typically has direct negative consequences for the rights and welfare of others, for instance hitting someone or taking someone else’s property. Within Social Domain Theory, such acts are referred to as first-order moral violations (Smetana, 2013; Turiel, 1983, 2002). We use the notion of “first-order” here to indicate that we are talking about violations with direct and immediate consequences, as opposed to consequences mediated by the presence of other norms (which would make the violation second-order). A famous example of a second-order moral violation is the act of wearing a bikini to a funeral (Rest, 1983; Turiel, 1989). This act is wrong in a first-order sense because it violates a social convention about which clothes to wear at a funeral (in many places), but it is also a second-order moral transgression because the act will have negative consequences for the well-being of the people grieving.

Another type of action often studied are actions with direct and experienced negative consequences for the agent, such as touching a hot plate. Tisak and Turiel (1984; Tisak, 1993) argued that these acts constitute a distinct category, which the authors referred to as (first-order) prudential transgressions. The fourth and final category discussed herein consists of actions deemed wrong even though they have no observable and experienced negative consequences for persons. Rather, such violations of social-conventional norms are considered wrong primarily because they violate an existing rule or command that serves to coordinate social interactions within a given context, for instance a dress code.

From 3–4 years of age, children draw distinctions between first-order moral norms (those pertaining to behaviors with direct consequences for the welfare and rights of others), prudential norms (those pertaining to behaviors with direct consequences to the welfare of the agent), and social conventional norms (those serving to coordinate social interactions) (Nucci & Weber, 1995; Schmidt et al., 2012; Smetana & Braeges, 1990; Smetana, 2006; Smetana et al., 2012; Tisak, 1993). However, past research has not investigated whether children see pragmatic norms (pertaining to inconvenience) as being distinct from first-order moral, prudential, and social conventional norms.

Pragmatic norms differ from first-order moral and prudential norms because the former pertain to behaviors that only indirectly affect people’s welfare. Pouring milk on the table (pragmatic) does not by itself harm anyone, even though someone will probably have to clean up the mess. In contrast, hitting someone (moral) or touching a hot plate (prudential) directly affects the welfare of individuals, either other people or the transgressor. Even young children may expectably begin to grasp the difference between pragmatic and first-order moral or prudential transgressions insofar as different social experiences are associated with these transgressions. For instance, the act of spilling food on purpose seems far less likely to elicit references to and expressions of pain than the act of hitting someone (Dahl, Campos, & Witherington, 2011; Dahl & Campos, 2013).

Pragmatic norms also differ from social conventions. Social conventions are usually defined as arbitrary ways of coordinating social interactions (Turiel, 1983), for instance by specifying when to use phrases of politeness. Social conventions are arbitrary in the sense that the normative difference between saying “Could you pass me the butter” and “Could you pass me the butter, please” is entirely determined by the norms entertained by the interactants. In contrast, pragmatic norms are not in the same sense arbitrary: Two broken plates on the kitchen floor constitute more mess than zero broken plates. Also unlike social conventions, pragmatic norms are not necessarily social norms in that they also specify how to interact with inanimate objects (for instance family property).

Proposing that pragmatic norms constitute a distinct category of norms does not imply the proposition that there is a pragmatic domain of thought (Gelman, 2010; Hirschfeld & Gelman, 1994; Turiel, 1983). Within Social Domain Theory, domains are defined as organized systems of thought about distinct aspects of the social (and non-social) world (Turiel, 1983, 1989). The moral domain is defined by concepts of welfare and rights of other people as well as fairness whereas the social conventional domain is constituted by concepts of social systems and the coordination of social interactions. Thoughts about prudential issues are organized around concepts of the agent’s own welfare, which have sometimes been considered to form a separate prudential domain (Tisak & Turiel, 1984) and sometimes been considered part of a personal or psychological domain (Nucci, Guerra, & Lee, 1991; Smetana, Jambon, & Ball, 2014). The concepts constitutive of each domain are reflected in children’s justifications of their judgments about moral, conventional, and prudential transgressions. For instance, young children are highly likely to refer to harm to a victim when justifying a judgment about a moral transgression (e.g. Nucci & Weber, 1995).

In contrast, there are at least three possible ways in which children could justify pragmatic norms, none of which would demonstrate the existence of a distinct pragmatic domain. Since pragmatic transgressions by definition create inconvenience, one possibility is that children see pragmatic transgressions as second-order moral transgressions (by creating inconvenience they indirectly affect the wellbeing of others). Another possibility is that pragmatic transgressions are construed as second-order prudential transgressions (their violation indirectly creates inconvenience for the transgressor). A third possibility is that children justify judgments about pragmatic transgressions by simply referring to the direct material disorder caused by the act (e.g. “it will get messy if we pour milk on the table”). Although this material justification is not by itself a moral, prudential, or conventional justification, it seems quite possible that references to mess-making are proxies for second-order moral or prudential considerations (e.g. making a mess is wrong because of how it affects others).

The present study investigated whether preschool-age children’s conceptions of pragmatic norms differ from their conceptions of first-order moral, prudential, and social conventional norms in three respects: justification categories, rule contingency, and severity judgments. These three dimensions have used in past research on children’s distinctions between types of norms (Nucci & Weber, 1995; Smetana & Braeges, 1990; Smetana et al., 2012; Tisak, 1993).

First, we hypothesized that children would think that it is wrong to violate pragmatic norms. Second, we hypothesized that children’s justifications for judgments about pragmatic transgressions would differ from their justifications for judgments about first-order moral, prudential, and conventional transgressions. Specifically, it was expected that children would justify judgments about pragmatic transgressions, but rarely other transgressions, by references to inconvenience to others (second-order moral), inconvenience to the transgressor (second-order prudential), or material disorder (including property damage).

The third hypothesis was that children would think pragmatic transgressions are wrong even in the absence of a rule, similar to first-order moral and prudential transgressions and unlike conventional transgressions. This was expected because, as argued, pragmatic transgressions have direct physical consequences that tend to interfere with people’s activities, irrespective of existing rules.

Finally, we hypothesized that pragmatic transgressions would be rated as less negative than moral and prudential transgressions because the consequences for the wellbeing of the transgressor or others are generally less severe for pragmatic transgressions (inconvenience) than for first-order moral and prudential transgressions (rights violations or harm). This hypothesis is also based on the finding that first-order moral and prudential transgressions respectively elicit more intense anger and fear responses from mothers and are enforced earlier in ontogeny than pragmatic transgressions (Dahl & Campos, 2013; Gralinski & Kopp, 1993; Smetana et al., 2000). In contrast, we expected pragmatic transgressions to be rated at similar levels of severity as conventional transgressions (Smetana & Braeges, 1990; Tisak, 1993).

1. Material and Methods

1.1. Participants

Fifty-eight children participated in the present study: 18 3-year-olds (10 female, Mage = 3.5 years, SDage = 0.31), 20 4-year-olds (13 female, Mage = 4.5 years, SDage = 0.30), 20 5-year-olds (8 female, Mage = 5.4 years, SDage = 0.33). One additional child was recruited but not included in the final sample because the child did not speak to the interviewer. Children were recruited from a university preschool and from a participant database at the UC Berkeley Institute of Human Development. Participants were predominantly non-Hispanic Caucasian and Asian American and from upper middle-class families.

1.2. Materials

Transgression scenarios were developed based on a reading of previous literature as well as pilot interviews with parents of young children (Gralinski & Kopp, 1993; Nucci & Weber, 1995; Smetana & Braeges, 1990; Smetana et al., 2012). A total of 16 scenarios involving norm violations were created. The four pragmatic scenarios were: pouring yogurt on the table (creating a mess), walking into the house with dirty shoes (creating a mess), throwing a plate on the floor (destroying family property), and asking for a cookie while mom is on the phone (interfering with mom’s ongoing activity). We also included four moral scenarios (hitting, shoving, calling names, stealing an apple), four prudential scenarios (running into the street, playing with an electric outlet, placing hand on hot stove, running down staircase and falling), and four conventional scenarios (playing with a toy during snack time, wearing a bathing suit to day care, not saying “please” when asking for something, standing during naptime).

For each scenario, two 5 x 6 inch color illustration cards were created to accompany the verbal presentation of the scenario in the child interviews. For children’s evaluation of transgressions, a five-point pictorial scale was created on a 8.5 x 11 inch sheet displaying five faces ranging from very happy (1) to very sad (5).

1.3. Procedures

In a warm-up session, children were introduced to the pictorial rating scale and trained on using this scale following procedures similar to those used in past research on social evaluation in young children (e.g. Killen, Mulvey, Richardson, Jampol, & Woodward, 2011; Lagattuta, Nucci, & Bosacki, 2010). The researcher told the child the following:

“First, I’m going to show you how to play a game. I really like pizza. So if you asked me how much I like pizza, I would point to this face [points to the most positive face] because it’s the happiest face. But I don’t like broccoli, so if you asked me how much I like broccoli I would point to this face [points to the most negative face] because it’s the saddest face. And I don’t really hate bread, but I don’t really like it either, so if you asked me how much I like bread I would point to this face [points to the neutral face] because it’s not a sad face but it’s not a happy face either.”

The researcher then asked the child to say one type of food he or she liked and type of food he or she disliked and to point to the appropriate face on the scale. If children pointed to one of the two happy faces for the one type of food they liked and one of the two sad faces for a type of food they disliked, this was considered a pass. Rating data were only included in the below analyses for children who passed this initial test.

Each child was interviewed about up to eight scenarios (two scenarios per transgression category, mean number of scenarios per child: 7.1). Children were presented with the four transgression categories in alternating order and were randomly assigned to one of four order conditions determined by a Latin Square. Only one child in the oldest age group received the naptime (conventional) scenario, as it was determined this scenario was not age appropriate for 5-year-olds.

The interviewer presented scenarios using the two picture cards. For instance, the spilling yogurt scenario (pragmatic) was presented as follows: “Here’s John. [Points to first picture card.] He’s eating yogurt. Suddenly, he decides to pour the yogurt all over the table. Look! [Points to second picture card.]” No scenario descriptions made mention of an existing rule against the behavior in question, and all descriptions were described as intentional. Next, the interviewer asked the child whether the protagonist’s action was all right (permissibility), why the protagonist’s action was or was not all right (justification), how much the child liked the protagonist’s action (severity, indicated by the child pointing to one of the faces on the five-point pictorial rating scale), and whether the action would be all right in a different school or home where there was no rule against the action (rule contingency). The interviews were videotaped to allow for coding of child responses and typically lasted 15–20 minutes.

1.4. Coding and Data Analysis

1.4.1. Data coding

Child judgments about whether or not an action was all right (permissibility, rule contingency) were coded as either “yes,” “no,” or “ambiguous”. Severity ratings were recorded by the interviewer. Justifications were classified into the following categories (hypothesized scenario type in parenthesis, see Table 1): inconvenience to the child, inconvenience to others, materials disorder (pragmatic), simple evaluation of act, harm to others, property rights (moral), harm to child (prudential), rules/authority, or social disorder (conventional). Fifteen percent of interviews were double-coded. Agreement for justification codes, assessed by Cohen’s κ, was .80.

Table 1.

Justification categories

| Justification | Definition | Example | Hypothesized scenario type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconvenience, self | Reference to inconvenience (no harm) for the agent, including sanctions | “He’ll have to clean up” | Pragmatic |

| Inconvenience, other | Reference to inconvenience (no harm) for others | “His mom will have to buy a new plate” | Pragmatic |

| Material disorder | Reference to material disorder or damage to objects | “The plate will break” | Pragmatic |

|

| |||

| Simple evaluation of act | Description of act itself in evaluative terms (nice, mean) | “It’s not nice.” | Moral |

| Harm, other | Reference to physical or psychological harm to others | “It’ll hurt him” | Moral |

| Property ownership | Statement that item belongs to someone else | “It’s Peter’s apple” | Moral |

|

| |||

| Harm, self | Reference to physical or psychological harm to agent | “He’ll get burnt” | Prudential |

|

| |||

| Rule/Authority | Statement implying that this type of act is against a rule or the command of an authority figure (e.g. teacher) | “It’s not swimming day” | Conventional |

| Social disorder | Statement indicating that action will disrupt social order | “The other kids will want to wear bathing suits too” | Conventional |

|

| |||

| Other | Gives no response or a response not falling in any of the above categories. | ||

2. Results1

2.1. Permissibility

Judgment data were analyzed using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with binomial error distribution and logit link function (Hox, 2010). Models included random intercept for subjects, a fixed linear effect of child age group (centered at the 4-year-old group), and a fixed effect of scenario type (pragmatic, moral, prudential, conventional). Hypotheses were tested using likelihood ratio tests on changes in model deviance. Judgments coded as “ambiguous” (3%) were not included in the analyses

Ninety-six percent of the time in pragmatic scenarios, and 100% of the time in moral, prudential, and conventional scenarios, children said the protagonist’s action was not permissible. There was no effect of scenario type, binomial GLMM: D(3) = 6.81, p = .078, or age group, D(1) = 0.003, p = .96, on permissibility judgments.

2.2. Justification Categories

Given the low frequency of judgments that the protagonist’s action was permissible, we only analyzed children’s responses why the action was not permissible. Children were generally readily able to explain their permissibility judgments. Only in one case did a child fail to provide at least one justification for why the action was not all right.

The initial justifications provided by each participant for a given scenario were first analyzed using multinomial logistic regression. The initial justification for a given scenario was defined as the first justification provided by the child in response to the prompt from the experimenter. (Only initial justifications were included in the multinomial model to avoid concerns about lack of independence between justifications provided in response to the same scenario.)

The multinomial regression model revealed a significant effect of scenario type on the initial response provided, D(27) = 494.39, p < .001. There was also a significant effect of age group on the type of justification initially provided, D(9) = 29.13, p < .001.

To further investigate how children’s justifications depended on scenario type, we analyzed data for each justification category separately. To make results more comparable to past research, all responses (initial and non-initial) were included in these analyses. Children provided responses in more than one category in 11% of cases. Binomial GLMMs were fitted to predict whether a participant provided a given justification type in a given scenario. Models included random intercept for subjects, a fixed linear effect of child age group (centered at the 4-year-old group), and a fixed effect of scenario type (pragmatic, moral, prudential, conventional).

Table 2 shows the proportion of cases in which a child provided at least one response falling into a particular justification category. All nine justification categories showed a significant association with scenario type (ps < .004). As predicted, the categories reflecting pragmatic concerns (inconvenience to self or other, reference to material disorder) were significantly more common in the pragmatic scenarios than in the three other scenario types.

Table 2.

Average proportion of situations in which children used each justification type

| Justification | Scenario Type

|

Situation effect (D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pragmatic | Moral | Prudential | Conventional | ||

| Inconvenience, self | .35a | .21b | .09c | .17b,c | 22.83*** |

| Inconvenience, other | .27a | .02b | .04b | .02b | 45.48*** |

| Material disorder | .24a | .00b | .00b | .04b | 58.87*** |

|

| |||||

| Simple evaluation of act | .09b,c | .22a | .05c | .17a,b | 19.85*** |

| Harm, other | .04b | .40a | .01b | .06b | 79.81*** |

| Property ownership | .00a | .06a | .00a | .01a | 13.79** |

|

| |||||

| Harm, self | .02b | .01b | .79a | .02b | 269.69*** |

|

| |||||

| Rule/Authority | .03b | .01b | .02b | .44a | 106.20*** |

| Social disorder | .00a | .01a | .00a | .05a | 18.02*** |

Note. Table shows proportion of scenarios within each type in which a given justification category was used (initial and non-initial justifications). Columns do not generally sum to 1.00 as some children provided justifications in multiple categories. The rightmost column shows the test statistic for the likelihood ratio test, which was compared to a χ2-distribution with three degrees of freedom.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Proportions with different subscripts differ significantly (ps < .05).

Inspections of the types of justifications provided for each of the pragmatic scenarios revealed some differences between the four (Table 3). The most common justifications for why it was wrong to spill yogurt and break the plate were inconvenience to the protagonist (spilling: 39% of participants; plate: 29%) and material disorder (spilling: 36%; plate: 33%). For the scenario where the child walks into the house with dirty shoes, the most common justifications were inconvenience to the protagonist (52%) and inconvenience to others (36%). Finally, the scenario in which the child asks the mother for a cookie while she is on the phone mainly elicited references to inconvenience to the mother (73%) (all situation effects on the use of a justification category: ps < .05).

Table 3.

Pragmatic scenarios: Average proportion of situations in which children used each justification type

| Justification | Scenario

|

Situation effect (D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cookie | Dirt | Plate | Yogurt | ||

| Inconvenience, self | .07 | .52 | .29 | .39 | 10.38* |

| Inconvenience, other | .73 | .36 | .10 | .09 | 25.13*** |

| Material disorder | .00 | .16 | .33 | .36 | 13.56** |

Note. Table shows proportion of scenarios within each type in which a given justification category was used (initial and non-initial justifications) for the four pragmatic situations (only justification categories associated with pragmatic scenarios shown). The rightmost column shows the test statistic for the likelihood ratio test, which was compared to a χ2-distribution with three degrees of freedom.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Consistent with previous research, references to harm to others were more common in moral scenarios, references to harm to the protagonist were more common in prudential scenarios, and references to rules and authority commands were more common in conventional scenarios (Table 2). Only one overall age group effect was found: References to harm to the protagonist were more common for older children than for younger children, D(1) = 12.15, p < .001.

We also wanted to test if older children were more likely than younger children to refer to consequences of their transgressions to others. For these purposes, we pooled the “inconvenience to others” and “harm to others” codes. There was a significant interaction between age group and scenario type in predicting the reference to consequences to others, binomial GLMM: D(3) = 10.54, p = .014. In the pragmatic scenarios, the 4- and 5-year-olds were more likely to refer to consequences to others than were the 3-year-olds (32% and 38% vs. 14%), D(1) = 3.84, p = .049. In contrast, there was no significant difference between 3-year-olds and 4- and 5-year-olds in the tendency to refer to consequences to others in the moral, prudential, and conventional scenarios.

2.3. Severity ratings

Severity ratings were analyzed using GLMMs with normal error distribution and identity link function and maximum likelihood estimation. Models included random intercept of subjects and fixed effects of scenario type and child age group. As maximum likelihood estimation can be sensitive to violations of model assumptions, non-parametric Friedman Rank Sum tests were also conducted. Results from the non-parametric tests yielded conclusions identical to those yielded by the normal GLMMs and are not reported.

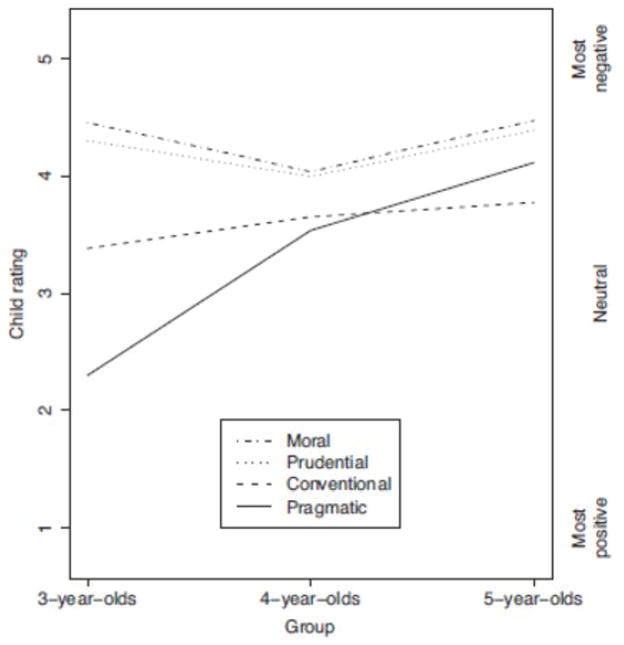

There was a significant interaction between scenario type and age group in predicting severity ratings, normal GLMM: D(3) = 12.79, p = .005. Separate analyses of scenario type revealed that the age group effect was significant for the pragmatic scenarios, D(1) = 8.92, p = .003, but not for the other three scenario types, ps > .46 (Figure 1). Three-year-olds rated pragmatic transgressions significantly less negatively than did 5-year-olds, Wald test: χ2(1) = 9.5, p = .002, whereas 4-year-olds did not differ significantly from the two other groups (ps ≥ .05). In fact, three-year-olds’ mean rating of pragmatic transgressions was positive. Yet, the effect of scenario type on severity rating remained significant even among the 5-year-olds, D(3) = 19.48, p < .001. Across age groups, moral and prudential transgressions were rated as more serious than conventional and pragmatic transgressions (Wald tests: ps < .001).

Figure 1.

Child mean severity ratings. Lines show the mean severity rating for each type of scenario for each age group.

2.4. Rule contingency

Rule contingency judgments were analyzed using binomial GLMMs with random intercept for participants and fixed effects of scenario type and child age group.

There was a significant effect of scenario type on whether or not a child said an action was permissible in a different school or home where there was no rule, binomial GLMM: D(3) = 17.37, p < .001. In conventional scenarios, children said the action was permissible 43% of the time, which was significantly higher than in pragmatic (31%), moral (27%), and prudential (26%) scenarios, Wald tests: ps < .035. There was no effect of age group on rule contingency responses, D(1) = 2.02, p = .16.

2.5. Latent Class Analysis

The above analyses could not directly assess whether the 16 norms violated in the scenarios constitute four clusters in “normative space.” To further investigate the clustering of norms, we analyzed the children’s judgment and justification data using Latent Class Analysis (LCA, Agresti, 2013; Lazarsfeld & Henry, 1968). LCA is a model-based approach to clustering that fits models assuming that variability in one or more (e.g. normal or binomial) indicator variables reflect one or more latent classes. Under this assumption, the LCA framework can be used to assess how well different numbers of latent classes fit the data, as well as to provide posterior probabilities that a particular observation (e.g. scenario) belongs to a given latent class.

We first transformed the severity ratings into a dichotomous variable (positive/neutral [rating: 1–3] vs. negative [rating: 4–5]). We also included children’s rule contingency judgments, but left out the permissibility judgments since we expected most children to say that the protagonist’s action was wrong across scenario types (Smetana & Braeges, 1990). In addition, we reduced the justification categories to four super categories based on the hypothesized association between norm type and justification type. These four super categories were: hypothesized pragmatic (material disorder, inconvenience to self, inconvenience to others), hypothesized moral (evaluation, harm to others, property), hypothesized conventional (rule/authority, social order), and hypothesized prudential (harm to self). For each situation, we noted whether a child had used at least one justification falling into the given category. The dataset used for the LCA thus consisted of one row for each scenario a child had responded to and one column for each of the six dichotomous indicator variables (severity and rule contingency, and use of hypothesized pragmatic, moral, prudential, and conventional justifications).

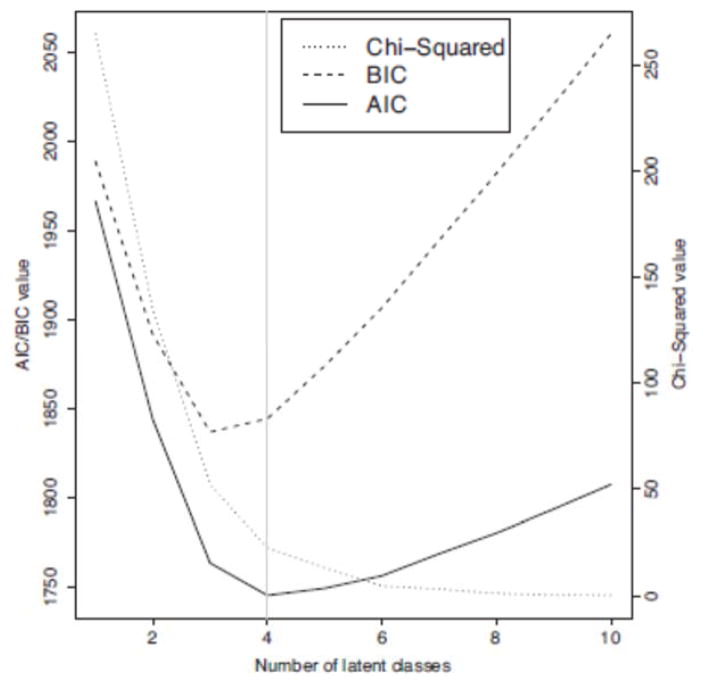

Model parameters were estimated using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm implemented in the poLCA package in R. Model fit was evaluated using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the Pearson χ2-statistic obtained from comparing the observed and expected frequencies after cross-tabulating the indicator variables (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, 1977; Linzer & Lewis, 2011). Estimation was re-initiated 20 times to minimize sensitivity to initiation values. The model results of interest were the conditional probabilities of observing a particular response (e.g. a negative evaluation) for members of a given class (e.g. pragmatic) as well as the “estimated” class memberships (i.e. the class most often given the highest posterior probability for a given scenario).

The results from the LCA on the individual responses were consistent with the hypothesized four-class structure. Figure 2 displays the three indices of model fit (AIC, BIC, Chi-Squared) as a function of the number of latent classes. As shown, the AIC showed a slight preference for four over five classes, the BIC showed a slight preference for three over four classes, and the Chi-Squared statistic showed that beyond the fourth class, relatively little is gained in fit to the observed data by adding another class. Considering these indices of fit as a whole, the four-class model thus appeared to fare the best.

Figure 2.

Fit indices as a function of number of latent classes. The lines show the values of the Pearson Chi-Squared (dotted line), Bayesian Information Criterion (dashed line), and the Akaike Information Criterion (solid black line) fit indices as a function of number of latent classes. The vertical grey line indicates the number of latent classes in the chosen model (four).

Next, we investigated the posterior probabilities that a given scenario fell into each latent class in the 4-class model. For each scenario, we determined whether it was more often given the highest probability for belonging to class 1, 2, 3, or 4. The results were again consistent with our expectations. The four pragmatic scenarios were most often classified into class 1, the four moral scenarios were most often classified into class 2, the four prudential scenarios were most often classified into class 3, and the four conventional scenarios were most often classified into class 4. We also looked at how scenarios were classified by the 3- and 5-class models, as fit statistics for these models were the most similar to the fit statistics of the 4-class model. The 3- and 5-class models both tended to place the four pragmatic scenarios in their own class. However, the 3-class model did not typically separate moral from conventional scenarios, whereas the addition of a fifth latent class barely affected the four-class structure (no scenarios were most often placed in the fifth class, but one conventional transgression – the failure to say “please” when asking for something – tended to be classified together with the moral transgressions). Thus, the selected model (four classes) as well as the most similar models (three and five classes) supported the conclusion that pragmatic norms constitute a distinct category of norms.

3. Discussion

The present results support the proposition that preschoolers think of pragmatic norms as distinct from first-order moral, prudential, and conventional norms. Children typically said pragmatic transgressions were not permissible because of inconvenience to the transgressor, inconvenience to others, or material disorder. The use of these three justification categories were significantly more common in pragmatic scenarios than in the moral, prudential and conventional scenarios. There were also some differences among the four pragmatic scenarios. For evaluations of spilling food and breaking a plate, the most common justifications involved references to inconvenience to the transgressor and material disorder. In contrast, justifications for why it is wrong to walk in with dirty shoes focused on inconvenience to the protagonist as well as to other people. Finally, as one might expect, the most common justification for why it was wrong to disturb the mother while she was on the phone was that it created inconvenience for her.

Children’s justifications of judgments about first-order moral, prudential, and conventional scenarios were similar to those found in past research (Nucci & Weber, 1995; Smetana & Braeges, 1990; Smetana et al., 2012; Tisak, 1993). Reference to harm to others was most common in response to moral scenarios, reference to harm to the child was the most common in response to prudential scenarios, and reference to rules or authority was most common in response to conventional scenarios.

In nearly all cases, children stated that the protagonist’s action was impermissible. However, as predicted, pragmatic transgressions (along with first-order moral and prudential transgressions) were less likely than conventional transgressions to be judged as permissible in the absence of a rule. This finding, along with the justification data, suggests that a large proportion of preschoolers recognized the direct consequences of pragmatic transgressions. The one exception was the act of disturbing the mother while she was on the phone, which was often considered permissible in the absence of a rule. It is possible that the children thought the mother did not consider it an inconvenience to hand the child a cookie if there was no rule against disturbing her.

Overall, children judged pragmatic and conventional transgressions as less severe than moral and prudential transgressions. Thus, even though many children recognized that pragmatic transgressions often affect themselves or others by creating inconvenience, these consequences appear to be seen as less serious than the psychological or physical harm caused by moral and prudential transgressions. Interestingly, 3-year-olds rated pragmatic transgressions as significantly less serious than did 5-year-olds. One possible explanation is that children become better at understanding the consequences pragmatic transgressions have for others. Indeed, when asked to justify judgments about pragmatic transgressions, the two oldest age groups were more likely to refer to consequences for other people than was the youngest age group. There may also be corresponding changes from three to five years of age in the beliefs children attribute to the transgressor, for instance the belief that transgressors in pragmatic scenarios are aware of the consequences of their actions for others (Killen et al., 2011). Another factor possibly contributing to older children rating pragmatic transgressions as more serious is that older children may have experienced that other people increasingly expect them to adhere to pragmatic norms (Gralinski & Kopp, 1993; Smetana et al., 2000).

The present findings do not demonstrate the existence of a pragmatic domain of thought. Rather, children justified pragmatic norms in several different ways, each of which may reflect considerations stemming from other domains of thought. Most obviously, the justification categories most strongly associated with the pragmatic scenarios reflect second-order moral (inconvenience for others) and second-order prudential (inconvenience for protagonist) considerations. The noted positive relation between child age and the references to inconvenience to others suggest that, with age, children increasingly view pragmatic transgressions as second-order moral transgressions.

The third justification category associated with pragmatic scenarios – material disorder – cannot immediately be classified as a second-order moral, prudential, or conventional justification. However, it is unlikely that material disorder justifications reflected conventional considerations since pragmatic transgressions were rarely considered permissible in the absence of a rule (unlike conventional transgressions). It is more likely that references to material disorder reflect implicit second-order moral or prudential considerations (e.g. “it’s wrong to create a mess because the mom has to clean up” [second-order moral]). Still another possibility is that children see material disorder as intrinsically bad (perhaps analogous to aesthetic judgments). This latter possibility would mean that children sometimes invoke uniquely pragmatic considerations, rather than second-order moral or prudential considerations, when judging pragmatic transgressions. Additional research is needed to investigate the nature of children’s material disorder justifications.

The present study also applied Latent Class Analysis to the study of children’s conceptions of norms. The results of these analyses supported the hypothesis that children see pragmatic norms as constituting a category distinct from first-order moral, prudential, and pragmatic norms. On a methodological level, these findings show that Latent Class Analysis is a potentially fruitful way of studying cognitive categories in children’s social understanding. In future studies using this technique, a greater number of variables (for instance representing different criterion judgments), scenarios, and participants should be included.

One limitation of the present study is the relatively small number of scenarios for each norm category. Within each of the four categories, there is likely to be a great deal of variability (Davidson, Turiel, & Black, 1983; Nucci & Turiel, 2009; Turiel, 1983). As noted above there were differences in the justifications elicited by the four pragmatic scenarios, and the same was true for instance for the moral scenarios: While the hitting scenario (moral) never elicited references to property ownership (a moral justification), the scenario where one child took an apple from another often did. The different concerns pertaining to a given category of norms, such as the pragmatic, may also show different developmental trajectories (Smetana, 2013; Turiel, 1983, in press).

There is also a need to observe the everyday interactions associated with children’s pragmatic transgressions in everyday life (see e.g. Killen & Smetana, 1999; Nucci & Turiel, 1978; Nucci & Weber, 1995; Smetana, 1989; Tisak, Nucci, & Jankowski, 1996). Maternal reports suggest that pragmatic transgressions do elicit different types of reactions from caregivers than do moral and prudential transgressions (Dahl & Campos, 2013). For instance, mothers typically reported being angrier in response to moral transgressions and more fearful in response to prudential transgressions, compared to pragmatic transgressions. Direct observational studies involving preschoolers are needed to understand how children’s social and non-social experiences may contribute to the development of their conceptions of pragmatic norms.

The present study showed that preschoolers’ conceptions of pragmatic norms differ from their conceptions of moral, prudential, and conventional norms. It seems likely that the specific pragmatic transgressions used in the present study are less relevant later in childhood and into adolescence, except in pathological cases. However, we would argue that conflicts over pragmatic transgressions arise across the lifespan; from quarrels between college roommates to marital disputes. Changes and consistencies in the nature and perceptions of these conflicts from infancy and into adulthood are an important area for future research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R03HD077155-01), and fellowships from the Norway-America Association, the UC Berkeley Institute of Human Development, and the Greater Good Science Center. We thank Elliot Turiel and Kelly Lynn Mulvey for comments on previous versions of the manuscript, Arthur Aron for statistical advice, Robert Nepomuceno for creating the illustrations used as stimuli, and the children who participated in the study.

Footnotes

No analyses revealed a significant effect of child gender and gender was therefore not included as a predictor in the reported models. Except when noted, interactions between fixed effects were not significant (ps > .05) and were not included in the final models. Because one conventional scenario (naptime) was dropped for the 5-year-olds, all analyses were re-run without the data from this scenario. These analyses yielded the same conclusions as those using all four conventional scenarios. Analyses reported below include all four conventional scenarios.

References

- Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Campos JJ. Domain differences in early social interactions. Child Development. 2013;84(3):817–825. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Campos JJ, Turiel E. Domain differences in early prohibitive interactions. Presented at the International Conference on Infant Studies; Minneapolis, MN. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Campos JJ, Witherington DC. Emotional action and communication in early moral development. Emotion Review. 2011;3(2):147–157. doi: 10.1177/1754073910387948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson P, Turiel E, Black A. The effect of stimulus familiarity on the use of criteria and justifications in children’s social reasoning. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1983;1(1):49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data via the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1977;39(1):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA. Modules, theories, or islands of expertise? Domain specificity in socialization. Child Development. 2010;81(3):715–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralinski JH, Kopp CB. Everyday rules for behavior: Mothers’ requests to young children. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(3):573–584. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld LA, Gelman SA, editors. Mapping the mind: Domain specificity in cognition and culture. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. 2. New York: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Mulvey KL, Richardson C, Jampol N, Woodward A. The accidental transgressor: Morally-relevant theory of mind. Cognition. 2011;119(2):197–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Smetana JG. Social interactions in preschool classrooms and the development of young children’s conceptions of the personal. Child Development. 1999;70(2):486–501. [Google Scholar]

- Lagattuta KH, Nucci L, Bosacki SL. Bridging theory of mind and the personal domain: Children’s reasoning about resistance to parental control. Child Development. 2010;81(2):616–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld PF, Henry NW. Latent structure analysis. New York: Houghton, Mifflin; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Linzer DA, Lewis JB. poLCA: An R package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;42(10):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Guerra N, Lee J. Adolescent judgments of the personal, prudential, and normative aspects of drug usage. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(5):841–848. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Turiel E. Social interactions and the development of social concepts in preschool children. Child Development. 1978:400–407. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Turiel E. Capturing the complexity of moral development and education. Mind, Brain, and Education. 2009;3(3):151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Weber EK. Social interactions in the home and the development of young children’s conceptions of the personal. Child Development. 1995;66(5):1438–1452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rest J. Morality. In: Flavell JH, Markman E, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 3: Cognitive Development. 4. New York: Wiley; 1983. pp. 556–629. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MFH, Rakoczy H, Tomasello M. Young children enforce social norms selectively depending on the violator’s group affiliation. Cognition. 2012;124(3):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Toddlers’ social interactions in the context of moral and conventional transgressions in the home. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25(4):499. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Social-cognitive domain theory: Consistencies and variations in children’s moral and social judgments. Handbook of Moral Development. 2006:119–153. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Moral development: the social domain theory view. In: Zelazo PD, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Developmental Psychology, Vol. 1: Body and Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 832–864. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Braeges JL. The development of toddlers’ moral and conventional judgments. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1990:329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Jambon M, Ball C. The social domain approach to children’s moral and social judgments. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of Moral Development. 2. New York: Psychology Press; 2014. pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Kochanska G, Chuang S. Mothers’ conceptions of everyday rules for young toddlers: a longitudinal investigation. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly (1982-) 2000;46(3):391–416. doi: 10.2307/23093738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Rote WM, Jambon M, Tasopoulos-Chan M, Villalobos M, Comer J. Developmental changes and individual differences in young children’s moral judgments. Child Development. 2012:683–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisak MS. Preschool children’s judgments of moral and personal events involving physical harm and property damage. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1993;39(3):375–390. doi: 10.2307/23087427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tisak MS, Nucci LP, Jankowski AM. Preschool children’s social interactions involving moral and prudential transgressions: An observational study. Early Education & Development. 1996;7(2):137–148. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed0702_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tisak MS, Turiel E. Children’s conceptions of moral and prudential rules. Child Development. 1984:1030–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of social knowledge: morality and convention. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. Domain-specific social judgments and domain ambigiuities. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1989;35:89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The culture of morality: social development, context, and conflict. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2014. Moral development. [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A, Missana M, Tomasello M. Three-year-old children intervene in third-party moral transgressions. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2011;29(1):124–130. doi: 10.1348/026151010X532888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]