Abstract

Poly(ADP‐ribosyl)ation, or PARylation, was first described over 50 years ago. Since then, our understanding of the biochemistry and enzymology of this protein modification has significantly progressed. PARylation has long been associated with DNA damage and DNA repair as well as genotoxic stress 1, 2. However, over the last two decades this has expanded to chromatin remodelling, DNA replication, transcriptional regulation, telomere cohesion and mitotic spindle formation during cell division, intracellular trafficking and energy metabolism 1. Most eukaryotes, except yeasts, have genes encoding poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerases (PARPs) and poly(ADP‐ribose) glycohydrolases (PARGs), and our knowledge on PARylation is primarily based on studies in metazoans. In plants, however, mechanistic understanding of the role of ADP‐ribosylation in stress response is still lacking. In this issue of EMBO Reports, Feng et al 3 identify the first set of PARylated plant proteins and show that in vivo PARylation of one of these proteins, a factor named DAWDLE, is important for its role in plant immunity.

Subject Categories: Immunology; Plant Biology; Post-translational Modifications, Proteolysis & Proteomics

PARP activity was described in wheat and tobacco nuclear extracts as early as the mid‐70s, but histones have been the only known PARylated proteins described in plants until now 2. Enzymes of the PARP family add ADP‐ribose mostly on the side chains of glutamate, aspartate and lysine using nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and generating mono‐ or poly‐(ADP‐ribosyl)ated modifications. Adding to the complexity is that poly(ADP‐ribose) chains can be linear or branched, although the significance of this has yet to be determined. PARGs remove ADP‐ribose units by trimming down poly(ADP‐ribose) (PAR) to either mono (ADP‐ribose) (MAR) or completely removing the modification. Similar to their function in metazoans, the expression and activity of PARPs in plants have mostly been associated with DNA damage and repair as well as with cell divisions 2. However, the involvement of PARPs and PARylation in these processes in plants is not understood at the molecular level, due in part to the lack of characterized PARylated proteins.

Land plants typically contain three types of PARPs 2 in sharp contrast to animal cells, which contain as many as 17 different PARPs. Some of the animal PARPS have specialized functions, such as the tankyrases involved in PARylation‐induced ubiquitination 4. The PARPs of the model plant Arabidopsis, AtPARP1 and AtPARP3, are most similar to human PARP1, whereas AtPARP2 is more similar to human PARP3. The other class of proteins with a PARP‐like domain are a plant‐specific family of SRO proteins and are typified by SRO and RCD1. Both of these SRO proteins bind transcription factors, but since SRO family members have variant catalytic triads and no ADP‐ribosylation by SRO family members has been shown, these enzymes are thought to lack PARP activity 5.

In Arabidopsis, AtPARP1, AtPARP2 and AtPARG1 are implicated in abiotic and biotic stress responses. Oxidative stress induces PARP activity, and inhibition of PARPs enhances abiotic stress tolerance 2. Consistent with this, RNA interference against PARPs in plants enhances tolerance to abiotic stress, indicating that PARylation may negatively regulate abiotic stress responses. Strikingly, genes encoding PARP and PARG are induced under abiotic stress conditions, suggesting that finely balanced ADP‐ribosylation is required under abiotic stress conditions.

In contrast, PARylation plays a positive role in biotic stress responses. Arabidopsis parg1 mutants display increased callose deposition and lignification, both late responses to pathogen perception, and infection with bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae enhances overall levels of PARylation in Arabidopsis 6. These results were corroborated by Feng et al 7 who identified AtPARG1 as a negative regulator of defence genes induced by pathogen‐associated molecular patterns. That work also showed that AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 are functional PAR polymerases, and AtPARG1 is a functional PAR glycohydrolase, which links PARylation to plant immunity. However, many questions remain unanswered.

In this issue of EMBO Reports, Feng et al 3 identify a large set of PARylated proteins from Arabidopsis using in vitro PARylation of microarrayed proteins. One of the identified PARylated proteins, a forkhead‐associated domain protein named DAWDLE (DLL), is functionally analysed in more detail. The dll mutants analysed have a stunted growth phenotype, and the name Dawdle also echoes the slow progress of the field, given that this is only the second plant protein shown to be PARylated in vivo. Insertion mutants of dawdle play a role in immune responses, as the plants are compromised in bacterial resistance. While early immune signalling events are unaffected in dll mutants, defence gene expression and callose deposition are reduced, indicating a role in late immune response. Feng et al 3 also show that the double mutant parp1/2 phenocopies the immunity phenotypes of dll mutants, tightening the link between the requirement for PARPs, PARylation and DLL in late immunity.

Instrumental to the identification of PARylation of DLL was the recent development of a method to identify remnants of ADP‐ribosylation on Glu and Asp residues 8. Using NH2OH treatment, poly(ADP‐ribose) chains are released from the acidic amino acid residues Asp and Glu, generating a hydroxamic acid derivative of the protein. Hydroxamic acid derivatives induce a 15.01 Da mass shift on Glu or Asp, which is easily detected by mass spectrometry 8. Using this method, Feng et al 3 show that several Glu residues are ADP‐ribosylated in DLL in vivo. A 12 Glu to Ala substitution mutant of DLL revealed that PARylation is functionally relevant for late immune responses. On the other hand, the mild developmental phenotype of dll6 can be complemented independently of mutations in the 12 Glu residues, indicating that the developmental role of DLL does not require ADP‐ribosylation.

Even though Feng et al did not gain further mechanistic insight into PAR‐regulated immunity, it is clear that DAWDLE paves the way to get on PAR with ADP‐ribosylation as a regulatory post‐translational modification in plant immune signalling. Much remains to be investigated, and complementary approaches to detect ADP‐ribosylated residues are required. The NH2OH method can only detect ADP‐ribosylated Glu and Asp residues, whereas Lys and Arg residues modified with ADP‐ribose go undetected. Methods to detect all ADP‐ribosylated residues, for example by using snake venom phosphodiesterase to create peptides with ADP‐ribosyl remnants amenable to MS analysis, are required to get a full picture on ADP‐ribosylation of proteins involved in stress responses. Global identification of in vivo ADP‐ribosylated proteins by these proteomics approaches will also broaden our view of PARylation in plant signalling beyond immunity.

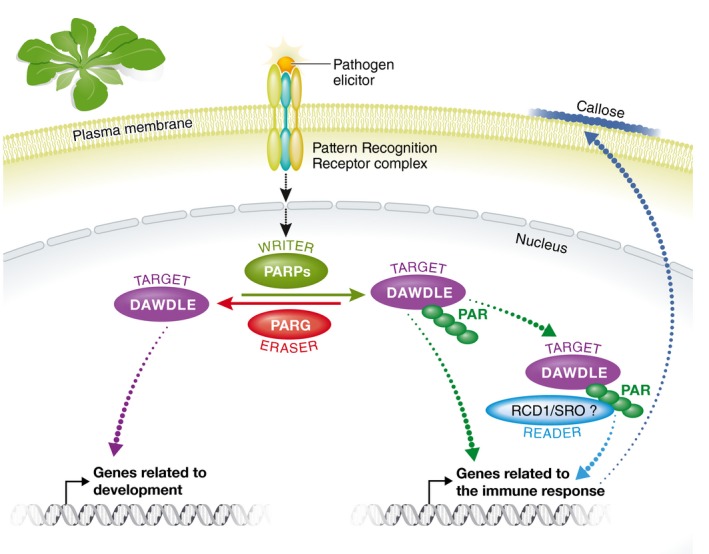

How does DAWDLE regulate plant immunity? It will be interesting to find out how PARylation affects DLL function and stability. By analogy to metazoans, PARylation could present a platform for the recruitment of other post‐translational modifications, such as ubiquitination. Although plants do not have tankyrases, the PARP enzyme recently shown to recruit the E3 ligase RFN146 to mediate PARylation‐induced ubiquitination 4, PARP binding regions such as WWE domains are present in plant proteins. With enzymes adding and removing ADP‐ribose units (PARPs and PARGs), plants already have so‐called writers and erasers (Fig 1). What we still miss in plants in order to have a functional coding system based on ADP‐ribosylation are readers, proteins with ADP‐ribose binding domains 9. RCD and other group I SRO family proteins contain a WWE domain capable of binding iso‐ADP‐ribose moieties in addition to a PARP‐like domain 5. They could very well be the plant equivalent of MAR/PAR readers. A plant equivalent PAR writer/reader/eraser system could function orthogonally to already established posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, that encode environmental information onto proteins 9, 10. The identification of DAWDLE and several other in vivo PARylated proteins by Feng and colleagues brings us one step closer to a full PAR decoding system. An immediate question to be answered next is whether PARylated DLL gets bound by RDC1 or related SRO proteins to modulate its function in plant immunity (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Hypothetical poly(ADP‐ribose) decoding system for plant immunity.

The scheme describes a decoding system for poly(ADP‐ribosyl) ation of DAWDLE consisting of a writer (PARP), eraser (PARG) and hypothetical reader (RCD1/SRO) for PARylation‐dependent immune responses.

Acknowledgements

I like to thank Sophien Kamoun for critically reading and feedback on the manuscript. FLHM was supported by Gatsby Charitable Foundation.

See also: B Feng et al (December 2016)

References

- 1. Kraus WL (2015) Mol Cell 58: 902–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lamb RS, Citarelli M, Teotia S (2012) Cell Mol Life Sci 69: 175–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feng B, Ma S, Chen S et al (2016) EMBO Rep 17: 1799–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DaRosa PA, Wang Z, Jiang X et al (2015) Nature 517: 223–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jaspers P, Overmyer K, Wrzaczek M et al (2010) BMC Genom 11: 170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adams‐Phillips L, Briggs AG, Bent AF (2010) Plant Physiol 152: 267–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feng B, Liu C, de Oliveira MV et al (2015) PLoS Genet 11: e1004936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang Y, Wang J, Ding M et al (2013) Nat Methods 10: 981–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Teloni F, Altmeyer M (2016) Nucleic Acids Res 44: 993–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lim WA, Pawson T (2010) Cell 142: 661–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]