ABSTRACT

RBJ has been identified to be dysregulated in gastrointestinal cancer and promotes tumorigenesis and progression by mediating nuclear accumulation of active MEK1/2 and sustained activation of ERK1/2. Considering that nuclear accumulation and constitutive activation of MEK/ERK not only promotes tumor progression directly, but also induces chronic inflammation, we wonder whether and how RBJ impairs host immune-surveillance via chronic inflammation and consequently supports tumor progression. Here, we report that higher expression of RBJ in human breast cancer tissue has been significantly correlated with poorer prognosis in breast cancer patients. The forced expression of RBJ promotes tumor growth and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, more accumulation of immune suppressive cells but less antitumor immune cell subpopulations were found in spleen and tumor tissue derived from RBJ force-expressed tumor-bearing mice. Furthermore, forced RBJ expression significantly promotes tumor cell production of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 by constitutive activating MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Accordingly, RBJ knockdown significantly decreases tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo, with markedly reduced production of IL-6. Administration of anti-IL-6 neutralizing antibody could reduce MDSCs accumulation in tumor tissue in vivo. Therefore, our results demonstrate that RBJ-mediated nuclear constitutive activation of ERK1/2 leads to persistent production of IL-6 and increase of MDSCs recruitment, contributing to promotion of tumor growth and metastasis. These results suggest that RBJ contributes to tumor immune escape, maybe serving a potential target for design of antitumor drug.

KEYWORDS: IL-6, immune escape, MDSCs, small GTPase, tumor metastasis

Introduction

Tumor-promoting chronic inflammation has been recognized a hallmark of cancer that substantially contributes to the tumor initiation, development, and progression of malignancies and affect therapeutic circumstance.1-3 Increasing clinical and experimental evidence indicates the pro-tumorigenic roles for the local and systemic immunosuppressive cell subsets that are key drivers in tumor-associated chronic inflammation.3-4 Among the immunosuppressive populations, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) has received attention as a potential link between inflammation and tumor progression.5-6 MDSCs derives from myeloid cells and be recruited to the tumor microenvironment, where they promote angiogenesis and sustain overall tumor growth, proliferation, spreading, and metastasis, in addition to establish tolerance and immune suppression.7-9 Emerging data suggest that MDSCs have specific prognostic value in various solid tumors, and the circulating MDSCs can be a marker for predicting clinical outcomes to cancer immunotherapy and chemotherapy in patients.10 Therefore, targeting MDSCs to control their expansion and recruitment as well as interfering with the molecular pathways of suppression appears to be a very clinically promising strategy for enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy approaches against cancer and benefit the patients.10-12

It has been reported that a variety of tumor-derived soluble factors involved in MDSCs expansion in peripheral lymphoid organs and recruitment to the tumor site, which profoundly affect myelopoiesis and mobilization of myeloid cells as well as their activation. It has been demonstrated that factors including cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), PGE2, SCF, GM-CSF, G-CSF, M-CSF, IL-6, and VEGF contribute to MDSCs expansion and activation. Among all these factors, M-CSF correlates with poor prognosis in breast cancer, in myeloblastic leukemia, in renal cell-carcinoma, and in bladder carcinoma.13-14 G-CSF promotes the mobilization and recruitment of haematopoietic stem cells and granulocytes MDSC resulting in tumor growth and metastasis.15-17 VEGF was also demonstrated to play an important role in MDSCs biology. In an experimental setup involving BALB/c-neuT mice, a transgenic model for spontaneous occurrence of mammary carcinoma, tumor load caused an abundant recruitment of MDSCs from bone marrow to spleen and peripheral blood, directly mediated by VEGF and not involving GM-CSF.18 Additionally, pro-inflammatory cytokine can also affect MDSCs recruitment and function. IL-1β, was shown to promote tumor progression in murine 4T1 mammary carcinoma, by indirectly inducing accumulation of MDSCs,19 PGE2 may partially mediate MDSCs accumulation through EP2 receptor.20 Neoplastic progression and accumulation of MDSCs can be restored by IL-6, probably through a direct action on these same myeloid cells that indeed express IL-6 receptor.21

RBJ is a member of the sixth subfamily of Ras-related small GTPase, which is characterized by the N-terminal GTP-binding domain (small GTPase domain) with a heat shock protein 70 (HSP70)-interacting J domain, and identified independently by our lab (GenBank No. AF178983, named as RabJ). Bioinformatic analysis demonstrates that RBJ represents a novel subfamily of Ras-related small GTPases, although it shares highest sequence homology with Rab proteins in small GTPase domain.22-25 Our previous studies demonstrated that RBJ is an oncogenic small GTPase required for gastrointestinal cancer tumorigenesis and progression by mediating nuclear accumulation of active MEK1/2 and sustained activation of ERK1/2.26 Here, we find that RBJ promotes tumor cells invasion/metastasis and growth in vitro and in vivo, enhances the expansion and accumulation of MDSCs. Furthermore, forced RBJ expression enhances pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 production by constitutive activating MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Administration of anti-IL-6 neutralization antibody significantly reduces MDSCs accumulation in vitro and in vivo, and IL-6 can increase COX2 expression of MDSCs. Accordingly, knockdown RBJ expression profoundly reverses these processes. Furthermore, higher expression of RBJ in breast cancer tissue markedly correlated with poorer prognosis in breast cancer patients. Therefore, our results demonstrate that RBJ-mediate nuclear constitutive activation of ERK1/2 leads to persistent production of IL-6 that contributes to MDSCs recruitment and COX2 expression, resulting in promotion of tumor growth and metastasis.

Materials and methods

Mice and cell lines

Female BALB/c mice and male C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks) were obtained from Joint Ventures Sipper BK Experimental Animal (Shanghai, China). All animal experiments were undertaken in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, with the approval of the Scientific Investigation Board of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China. The 4T1 mammary carcinoma cell line derived from BALB/c origin and others cell line including melanoma cell line B16 and B16F10 derived from C57BL/6 origin were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in RPMI1640 complete medium (PAA Laboratories, Linz, Austria) supplemented with 10% FCS (PAA Laboratories) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Reagents

ELISA kits for murine PGE2, G-CSF, M-CSF, IL-6, CXCL1, CXCL2, VEGF, IL-10, TGF-β, TNF-α, and IL-1β were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Antibody against COX2 or Gr1, and fluorescein-conjugated mAbs to CD3, CD4+, CD8+, CD11b, Gr1, and isotype control mAbs were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Purified rat anti-mouse Gr1, and Alexa Fluor 594 rabbit anti-rat IgG were from BD Pharmingen. Antibody against RBJ was from Abnova (Taipei, Taiwan). Antibody against p-ERK, IL-6R/CD126 were from Cell Signaling Technology. U0126, an ERK MAPK inhibitor, was from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Stattic, a p-Stat3 signal inhibitor, was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Neutralizing Ab to IL-6 and isotype controls were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Plasmids vector construction, cell culture, and transfection

The GFP- and Flag-tagged recombinant vector encoding mouse RBJ was constructed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based amplification, then sub-cloned into the pcDNA3.1 eukaryotic expression vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The clone was confirmed by DNA sequencing.26 Transfection of plasmids into eukaryotic cells was performed as recommended by the manufacturer using JetPEI (Illkirch, France). For stably force-expressed or silenced transfected cell clones were selected in 800 μg/mL G418 for 3–4 weeks and then confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blot for the expression of RBJ.

Reverse-transcription PCR and quantitative PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). 2 μg total RNA was used in a 20 μL reverse-transcription reaction using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Toyobo), and then the cDNA was diluted into 160 μL as the template of the next quantitative PCR. Quantitative PCR was performed on a MJR Chromo4 Continuous Fluorescence detector (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Tissue arrays and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Breast-infiltrating duct carcinoma (BIDC) microarrays (HBre-Duc150Sur-01 and HBre-Duc150Sur-02) were obtained from SHANGHAI OUTDO BIOTECH CO.LTD (Shanghai, China). Detailed information on the age, gender, and tumor histology of patients could be found at www.superchip.com.cn. RBJ Ab, phosphorylated ERK Ab, or anti-IL-6R Ab were used at dilutions of 1:200, 1:300, or 1:250, respectively. The EnVision detection system (Dako, Denmark) was used. Digital imaging was performed using the software LAS V4.5 (Leica DM 2000)

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Tissue sections of spleen or tumor tissue were analyzed by IF as described previously.27 RBJ, phosphorylated ERK and Gr1 antibodies were used at the dilution of 1:200, 1:300, or 1:50, respectively. The fluorescent-labeled second antibodies were used at the dilution of 1:100. Digital imaging was performed using the software LAS V4.5 (Leica DM 2000).

Assay for cytokines

TGF-β, IL-10, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, G-CSF, VEGF, M-CSF PGE2, CXCL1, and CXCL2 in the supernatants of cultured cells were assayed using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems).

Assay for cell chemoattraction in vitro

Chemoattraction of immune cell subsets was performed in 3.0 μm pore size polyethylene terephthalate (PET) track-etched membrane cell-culture inserts (BD Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The supernatants of transfected cells (600 μL) were 3-fold diluted with RPMI1640 medium. In the experiment to confirm the role of IL-6 in the cell chemoattraction, anti-IL-6 antibody (5, 10 μg/mL), was pre-added into the supernatants for 2 h, anti-IgG Ab as a control. CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs (5 × 105) purified from bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice using FACSDiVa sorting system (Becton Dickinson) were placed into transwell inserts. Four hours after incubation at 37°C, the cells that had migrated into low chambers were harvested, suspended in 300 μL PBS and counted by FACSCalibur in low rate within 52 sec and analyzed by CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) as described previously.28

In vitro migration and invasion assay

Tumor cell migration and invasion were evaluated by means of chemotaxis and chemoinvasion experiments respectively in a 24-well modified Boyden chamber. Tumor cell migration was assayed in a 24-well Transwell cell culture chamber with filters of 8.0 μm pore size according to the manufacturer's instruction (Costar, Cambridge, MA). The invasiveness of tumor cells was evaluated by the Matrigel (10 μm thickness and 8 μm pore size ) assay using 24-well Boyden chambers (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) containing a polycarbonate membrane according to the manual. 5 × 104 cells in 500 μL RPMI 1640 medium were added to the upper compartment of chamber and incubated at 37°C for 12 h (for migration assay) or 24 h (for invasion assay) in 5% CO2. After incubation, filters were harvested, fixed with methanol, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet and counted under a microscope in 10 pre-determined fields at 200-fold magnification. Results were presented as mean ± SD of each field.

Preparation and observation of tumor-bearing mice

For in vivo pulmonary metastasis assay, 5 × 105 cancer cells suspended in 200 μL HBSS were injected subcutaneously into the abdominal mammary gland of Balb/c mice (for 4T1 cells) or injected iv. into C57BL/6 mice (for B16 cells). The pulmonary metastases were evaluated 3 weeks later by counting the number of lung metastatic nodules under the assistance of dissecting microscope. For the experiments of observing 4T1 mammary carcinoma tumor growth in vivo, 5 × 105 cancer cells were injected subcutaneously into the shaved right flank of Balb/c mice. In some experiments, 125 μg anti-IL-6 Ab and control Isotype (mouse IgG) were i.p injected once a day during 21 d. Tumor sizes were measured with a caliper after tumor inoculation every 2–3 d and the tumor volumes were determined by measuring of the maximal (a) and minimal (b) diameters and calculated by using the formula a × b2/2. The survival of the tumor-bearing mice was monitored daily. Mice were sacrificed on day 21 after tumor inoculation, and the number and the ratio of Gr1+CD11b+ MDSCs in spleen and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were analyzed by FACS. Experiments were performed three times and each group contained 10 mice.

Isolation of mononuclear cells (MNC) from liver, lung, and tumor tissues

Tumor mass, lung, and liver obtained from tumor-bearing mice were digested with collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 h, and then the single-cell suspension was passed through a 40-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon). MNC populations were separated by centrifugation through a Percoll gradient. Cells were collected, washed in PBS, and resuspended in 40% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) in complete RPMI 1640 medium. The cell suspension was then gently overlaid onto 70% Percoll and centrifuged. MNC were collected from the interface, washed twice in PBS, and re-suspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium.

Flow cytometry assay

Splenocytes were prepared as described previously.27,28 For the isolation of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIIC), tumor tissues were cut into small fragments and incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1 mg/mL collagenase (4 mL/g of tumor tissue; Sigma) at 37°C for 45 to 60 min. Then single-cell suspension was prepared by pressing the digested tumor tissues through a stainless mesh. After hypotonic lysis of red blood cells, the TIIC were collected by centrifugation on a Ficoll gradient. Then the splenocytes and TIIC were labeled for flow cytometric analysis with a FACS LSRII (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed with FACSDiva software. By using, FITC, PE, PE-Cy7, PerCP-Cy5.5, or APC Abs recognizing CD3, CD4+, CD8+, CD11b, or Gr1. For purification of Gr1+CD11b+ MDSCs, isolated MNC from signal cells from liver, lung, peripheral blood, spleen, and tumor tissues were stained with anti-Gr1 FITC and anti-CD11b PE, and then Gr1+CD11b+ MDSCs were sorted by a MoFlo high-speed cell sorter (DAKO). The purity was confirmed by flow cytometry to be > 95%.

Western blotting

Western blot was performed as previously described.27,28 Briefly, cells were lysed and protein concentration was determined by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were then blotted with the indicated antibodies. Proteins were visualized using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate, as instructed by the manufacturer (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were independently performed three times in triplicate. Results are given as means plus or minus the standard error (SE) or standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were performed using Student t test, whereas comparisons between multiple groups were done using AVONA test, with a value of p values <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. For analyzing survival of BIDC patients, log-rank test in SPSS 17.0 was used with the p values shown.

Results

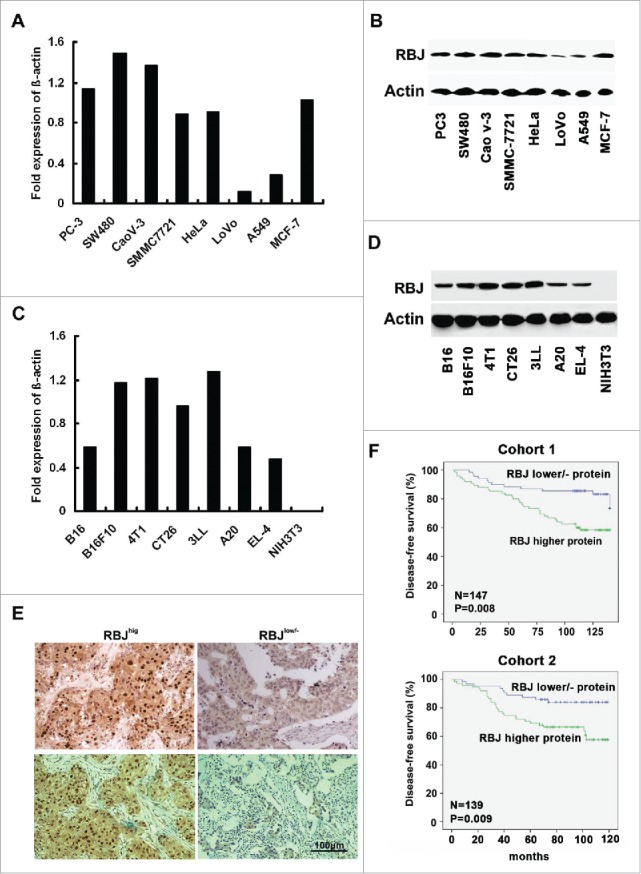

High expression of RBJ in breast cancer tissue correlates with poorer prognosis of breast cancer patients

We detected the expression of RBJ in various human and mouse cancer cell lines by real-time PCR and Western-blot assay, and found that RBJ is expressed in almost all human and mouse cancer cell lines detected, especially with higher expression in human MCF-7 and mouse 4T1 breast cancer cell lines and almost no expression in mouse NIH3T3 cell line (Figs. 1A–D). The data indicated that RBJ is generally expressed in various human and mouse cancer cell lines, and highly expressed in breast cancer. Considering that RBJ has been identified an oncogenic small GTPase required for gastrointestinal cancer tumorigenesis and progression,26 we speculated that RBJ may be involved in breast cancer progression. Then, we detected the expression of RBJ in tissue microarrays of human BIDC derived from 147 (Cohort 1, with patient's survival information) and 139 (Cohort 2, with patient's survival information) by IHC. The results showed that RBJ expression in nucleus of cancer cell was found in 53.06% (78/147, Cohort 1) and 53.96% (75/139, Cohort2) of BIDC patients (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, the BIDC patients with higher expression of RBJ in nucleus of cancer cell showed a shorter disease-free survival time (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these results suggest that higher expression of RBJ in BIDC tissue may contribute to breast cancer progression.

Figure 1.

The expression of RBJ in cancer cell lines and human breast-infiltrating duct carcinoma (BIDC) tissues. (A, B) Analysis of RBJ expression in human cancer cell lines by real-time PCR and Western blot. (C, D) Analysis of RBJ expression in mouse cancer cell lines by real-time PCR and Western blot. (E) IHC analysis of RBJ expression in human BIDC tissues (Cohort 1, n = 147; Cohort 2, n = 139). The representative images for higher and lower/negative expression of RBJ in human BIDC tissues derived from Cohort 1 (upper panel) or Cohort 2 (lower panel) were presented, bar represents 100 μm. (F) Correlation of higher expression of RBJ in human BIDC tissues with reduced disease-free survival in human BIDC patients. Kaplan–Meier survival curves of disease-free survival in Cohort 1 and Cohort 2, survival data were analyzed by log-rank statistics, and the p value is indicated.

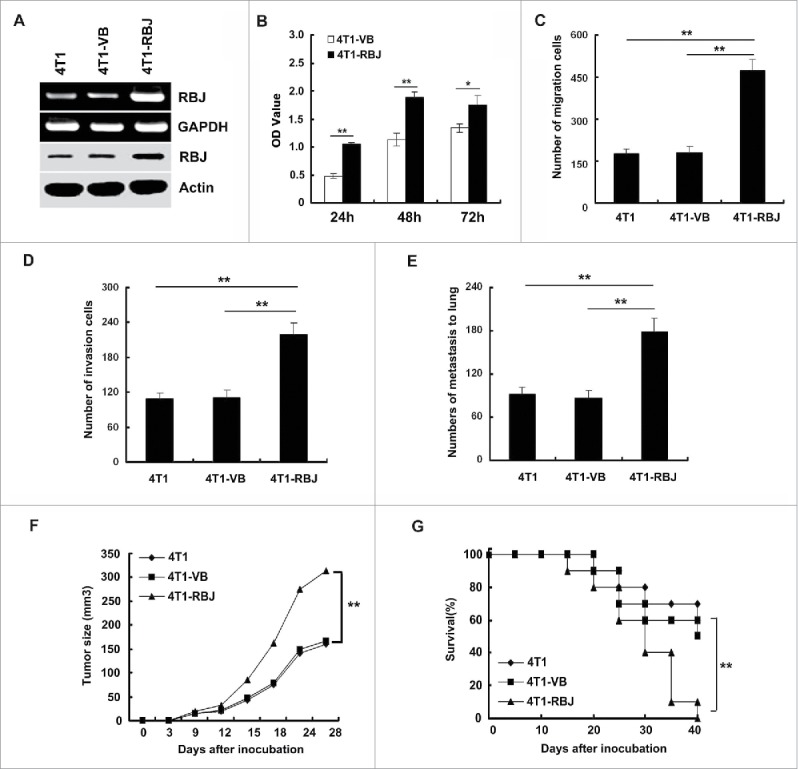

RBJ promotes tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo

Next, we investigated the effect of RBJ on tumor progression. RBJ force- or silence-expressed transfected cell clones were selected in 800 μg/mL G418 for 3–4 weeks and the effect of force- or silence-expressed RBJ was confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blot. The force- or silence-expressed RBJ in transfected 4T1 breast cancer cell line was showed in Figs. 2A and 3A. Next, we analyzed the proliferation of RBJ force-expressed 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells in serum-free condition, and found that forced expression of RBJ significantly increased cancer cell proliferation (Fig. 2B), and markedly enhanced migration and invasion of 4T1 mammary carcinoma in vitro (Figs. 2C and D). Furthermore, in vivo pulmonary metastases assay demonstrated that RBJ force-expressed in 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells exhibited more profound metastasis to lung (Fig. 2E). In addition, RBJ force-expressed B16 melanoma cells also exhibited the enhanced cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro and more profound metastasis to lung in vivo (Figs. 3D–F). Accordingly, forced expression of RBJ in 4T1 cells significantly accelerated tumor growth and reduced the survival of the tumor-bearing mice than that of mice bearing parental 4T1 cells or 4T1-VB cells (Figs. 2F and G). Collectively, the results indicate that forced expression of RBJ promotes tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 2.

Forced expression of RBJ enhances tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. (A) The identification of the effective forced expression of RBJ in 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells by RT-PCR (upper panel) and Western blot (lower panel). (B) Forced expression of RBJ promoted 4T1 tumor cell proliferation in serum-free condition. (C, D, E) Forced expression of RBJ increased 4T1 tumor cell migration, invasion in vitro and metastasis to lung in vivo. Data were showed as mean value ± SD of three independent experiments with similar results, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (F, G) Forced expression of RBJ enhanced 4T1 tumor growth and reduced survival of tumor-bearing mice. Data points represent the mean value ± SD from 10 mice per group for E and F, respectively, **p < 0.01. Survival data were analyzed by log-rank statistics, and the p value was denoted, **p < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of RBJ reduces tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. (A) The identification of effective RBJ knockdown in 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells by RT-PCR (upper panel) and Western blot (lower panel). Knockdown of RBJ reduced 4T1 tumor cell and B16 tumor cell migration, invasion in vitro (B, D) and metastasis to lung in vivo (C, E, F). Data were showed as mean value ± SD of three independent experiments, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (G, H) Knockdown of RBJ reduced 4T1 tumor growth and prolonged survival of tumor-bearing mice. Data points represent the mean value ± SD from 10 mice per group for E and F, respectively, **p < 0.01. Survival data were analyzed by log-rank statistics, and the p value was denoted, **p < 0.01.

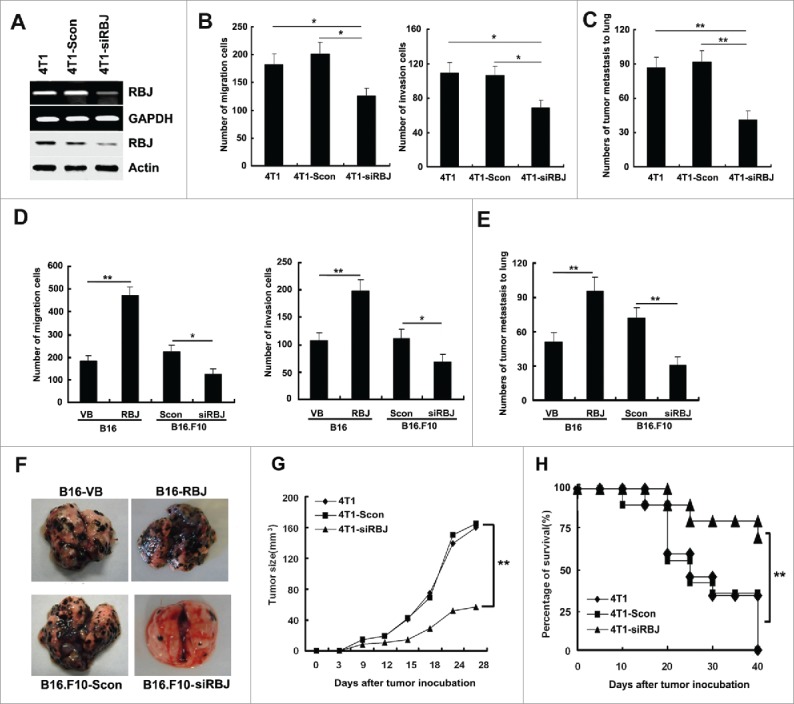

Knockdown of RBJ reduces tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo

Inspired by the above observation that forced expression of RBJ in tumor cells can promote tumor progression in vitro and in vivo, we wonder whether and how knockdown of RBJ affects cancer progression? Then, we detected the capability of migration and invasion of the stably silenced transfected 4T1 cells (4T1-siRBJ) and control transfected cells (4T1-Scon) both in vitro and in vivo. Knockdown of RBJ profoundly reduced 4T1 mammary carcinoma migration and invasion in vitro, and disrupted tumor metastasis to lung in vivo (Figs. 3B–C). Furthermore, the significantly reduced tumor growth and the increased survival of tumor-bearing mice subcutaneously inoculated with 4T1-siRBJ cells were observed as compared with that of mice-bearing parental 4T1 cells or 4T1-Scon cells (Figs. 3G and H). Additionally, knockdown of RBJ also significantly reduced B16F10 cell migration and invasion in vitro and metastasis to lung in vivo (Figs. 3D–F). Together with above data, we conclude that RBJ expression in tumor cell contributes to tumor progression and knockdown of RBJ in tumor cell inhibits tumor progression.

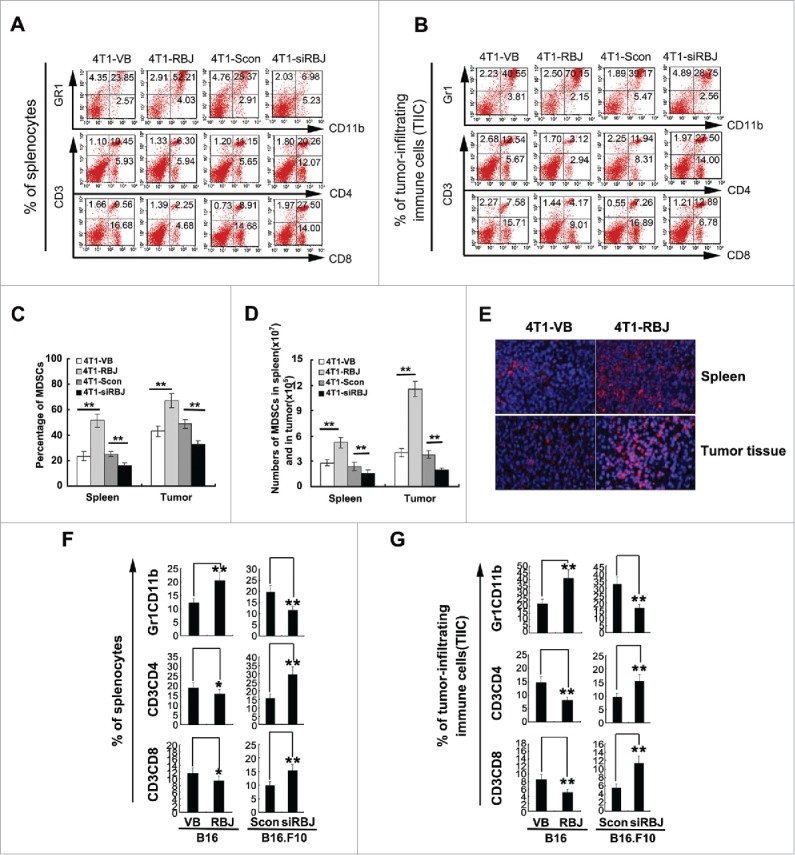

RBJ increases expansion and accumulation of MDSCs in spleen and tumor tissues of tumor-bearing mice

Our previous study showed that RBJ can directly promote tumor cell growth,26 we wonder whether chronic inflammation and immunosuppression is also involved in RBJ-medicated tumor progression. So, we investigated the role of RBJ in medicating chronic inflammation and immunosuppression. We analyzed the local and systemic immune cell subsets of the tumor-bearing mice subcutaneously transplanted with 4T1 transfectants, and found that the mice-bearing 4T1 force-expressed RBJ (4T1-RBJ) displayed more accumulation of MDSCs (Gr1+CD11b+) in both the spleen (Fig. 4A) and tumor tissue (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the frequencies of CD3+CD4+ T cells, and CD3+CD8+ T cells were decreased to different extent in both the spleen (Fig. 4A) and tumor tissue (Fig. 4B). On the contrary, mice-bearing RBJ-silenced tumor cells (4T1-siRBJ) displayed significantly decreased accumulation of MDSCs and increased frequency of CD3+CD4+ T cells, and CD3+CD8+ T cells in both the spleen and tumor tissue, as compared that of the control mice (Figs. 4A–B). As shown in Figs. 4C–E, the absolute numbers and percentage of MDSCs were more markedly increased in the spleen and tumor tissue formed by 4T1-RBJ than that of in the tumor tissue formed by 4T1-VB cells (Figs. 4C–E), and the significantly reduced infiltration of MDSCs in the spleen and tumor tissue was observed in the mice inoculated with RBJ-silenced 4T1 cells (4T 1-siRBJ) as compared with that in the control (4T1-Scon) (Figs. 4C and D). Additionally, the similar results had been observed in the models inoculated with B16 or B16.F10 cells. Inoculation of B16 cells with the forced RBJ expression accumulated more MDSCs in both the spleen (Fig. 4F) and tumor tissue (Fig. 4G), accordingly, the frequencies of CD3+CD4+ T cells and CD3+CD8+ T cells were decreased. In contrast, inoculation with RBJ-silenced B16.F10 cells markedly reduced MDSCs recruitment, and increased the frequency of CD3+CD4+ T cells and CD3+CD8+ T cells in the in spleen and tumor tissue of mouse models (Figs. 4F and G). Collectively, expression of RBJ in tumor tissues can expand and recruit more immunosuppressive MDSCs in spleen and tumor tissue, and RBJ-medicated recruitment of MDSC is verified to be general in other tumor-bearing mice, not specific to breast cancer mouse model.

Figure 4.

RBJ contributes to tumor-induced immunosuppression in vivo. (A, B) Frequencies of immune cell subpopulations (Gr1+CD11b+ MDSCs, CD3+CD4+ T cells and CD3+CD8+ T cells) in the spleen (A) and tumor nodules (B) of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. 5 × 105 4T1 cells with forced expression of RBJ (4T1-RBJ) and mock control (4T1-VB), RBJ knockdown (4T1-siRBJ) and silence control (4T1-Scon) were injected subcutaneously into the abdominal mammary gland of female Balb/c mice. Two weeks later, the splenocytes and the tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIIC) were isolated, stained with fluorescent Abs as indicated, and analyzed for frequency of immune cell subpopulations by FACS. The representative plots derived from 10 mice (n = 10) were shown. (C, D) The percentage and absolute numbers of MDSCs in splenocytes and TIIC were analyzed, the results represent mean value ± SD of three independent experiments with similar results **p < 0.01. (E) The tumor tissues from the tumor-bearing mice were excised, fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with anti-Gr1 antibody and anti-rat Alexa 647 for analyzing MDSCs by IF, nucleus was strained by DAPI. Original magnification, ×200. Frequencies of immune cell subpopulations including Gr1+CD11b+MDSCs, CD3+CD4+ T cells, and CD3+CD8+ T cells in the spleen (F) and tumor nodules (G) of B16 or B16.F10 tumor-bearing mice, data were showed as mean value ± SD of three independent experiments, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

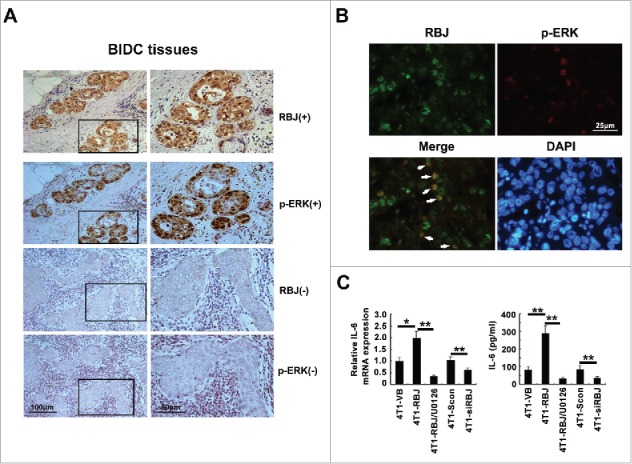

RBJ enhances tumor cell production of IL-6 by nuclear accumulation and constitutive activation of ERK

It has been identified that nuclear sustained activation of ERK contributes to RBJ-medicated gastrointestinal cancer tumorigenesis and progression.26 So, we detected the activation and location of ERK or RBJ in human breast cancer tissues derived from BIDC patients. The results showed that nuclear accumulation and activation of ERK, further co-localization with RBJ, were found in RBJ+ BIDC tumor tissues. However, in RBJ− tumor tissues, this phenomenon did not be detected (Figs. 5A and B). Commonly, constitutive activation of ERK also induces inflammatory cytokine production resulting in chronic inflammation. It has been reported that tumor-derived anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory factor such as TGF-β, IL-10, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, G-CSF, VEGF, M-CSF PGE2, CXCL1, and CXCL2 profoundly affect myelopoiesis and mobilization of myeloid cells as well as their activation.17 So, we detected secretion of above cytokines in the supernatant derived from cultured transfectant cells. The results showed that forced expression of RBJ significantly enhanced IL-6 expression and secretion, and knockdown of RBJ markedly decreased the expression and secretion of IL-6 (Fig. 5C). However, no significant increase of TGF-β, PGE2, G-CSF, M-CSF, CXCL1, CXCL2, and VEGF secretion was found (data not shown). And IL-10, TNF-α, and IL-1β was not detectable in the supernatant of cultured cells (data not shown). Furthermore, we found that the specific inhibitor of MEK/ERK (U0126) could significantly reduce RBJ-medicated IL-6 secretion, suggesting RBJ-medicated IL-6 production depends on nuclear accumulation of sustained activation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results suggest RBJ-medicated nuclear accumulation and constitutive activation of MEK/ERK contributes to pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 production by tumor cells.

Figure 5.

RBJ increases IL-6 production via nuclear accumulation and constitutive activation of ERK in tumor cell. (A) IHC analysis of RBJ and p-ERK expression in serial section of human BIDC tissues. One representative image for double positive expression of RBJ and p-ERK was shown, bar represents 100 μm (left panel) or 50 μm (right panel). (B) The nuclear co-localization expression of RBJ and p-ERK in human BIDC tissues was detected by IF. One representative image was shown, bar represents 25 μm. (C) The 4T1 transfectants (4 × 105 /mL) cultures under normal conditions (10% FCS) with or without MEK/ERK inhibitor (U0126, 30 μM) were analyzed for the expression of IL-6 either by real-time PCR (left panel) and ELISA (right panel). Results were presented as mean ± SD. *p< 0.05, **p < 0.01.

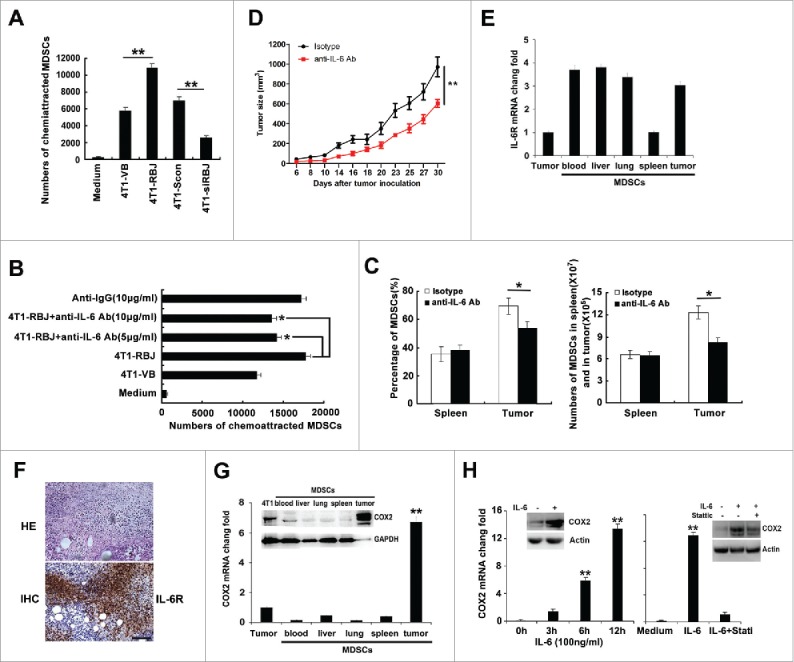

RBJ-promoted production of IL-6 increases the accumulation and immunosuppressive function of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs

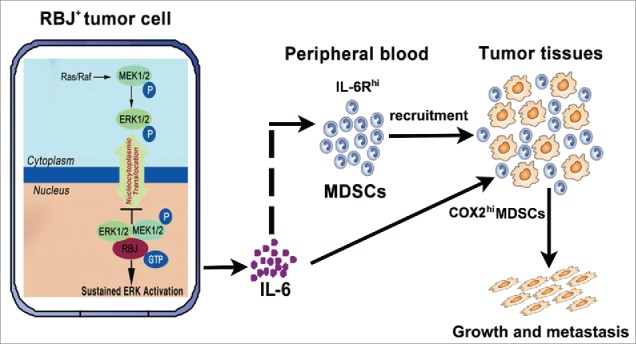

By the in vitro chemoattraction assay, we found that the culture supernatant derived from RBJ force-expressed 4T1 cells (4T1-RBJ) could recruit more Gr1+CD11b+ MDSCs than that derived from control 4T1 cells (4T1-VB) (Fig. 6A). Accordingly, knockdown of RBJ significantly reduced MDSCs accumulation (Fig. 6A). Then, we asked whether RBJ-promoted IL-6 production involved in MDSCs recruitment? As shown in Fig. 6B, blockade of IL-6 profoundly reduced the recruitment of MDSCs in vitro by 4T1-RBJ supernatant. To further confirm the conclusion in vivo, 4T1-RBJ cells were injected subcutaneously into the shaved right flank of Balb/c mice, and then anti-IL-6 neutralizing Ab and control isotype were i.p injected respectively once a day during 21 d. The number and the ratio of MDSCs in spleen and TIL were analyzed by FACS. We found that administration of anti-IL-6 neutralization Ab inhibited MDSCs accumulation into tumor tissue, but did not reduce MDSCs recruit into the spleen of 4T1-RBJ-bearing mice (Fig. 6C). Moreover, administration of anti-IL-6 neutralization Ab could profoundly inhibit tumor growth in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 6D). Then, we investigated whether does IL-6-medicated MDSCs migration require IL-6 and IL-6 receptor (IL-6R/CD126) interaction in the local tumor tissue? We detected the IL-6R expression in MDSCs isolated and sorted from peripheral blood, liver, lung, spleen, and tumor derived from 4T1-RBJ-bearing mice and found that IL-6R expression in spleen was lower compared to that in others organ, and tumor tissue infiltrated MDSCs expressed higher level IL-6R (Figs. 6E and F). So, RBJ-medicated IL-6 secretion may enhance MDSCs recruitment in local tumor tissue in a paracrine manner. In addition, we found that COX2 expression in tumor-infiltrating MDSCs was significantly higher than that of MDSCs isolated from others organ. Exogenous IL-6 indeed enhanced COX2 expression in sorted MDSCs in both mRNA and protein level, which depended on p-Stat3 signal activation (Figs. 6G and H). Taken together, RBJ-promoted IL-6 production contributes to MDSCs recruitment and COX2 expression resulting in promotion of cancer immune escape and progression (Fig. 7).

Figure 6.

RBJ-promoted tumor cell production of IL-6 increases accumulation and immunosuppressive function of MDSCs in tumor tissues. (A) The supernatant of 4T1-RBJ cells recruited more MDSCs, and knockdown of RBJ reduced MDSCs accumulation as detected by in vitro transwell assay. (B) Blockade of IL-6 in 4T1-RBJ supernatant profoundly reduced the recruitment of MDSCs in vitro. The supernatant of 4T1-RBJ cells was collected and 3-fold diluted, with or without addition of anti-IL-6 neutralizing Ab (5, 10 μg/mL) or isotype anti-IgG control (10 μg/mL) for 2 h. The supernatant was used for in vitro chemoattraction of MDSCs. Data were presented as mean value ± SD of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (C) Effect of anti-IL-6 neutralizing antibody on the expansion and accumulation of MDSCs in the spleen and tumor tissues of 4T1-RBJ-bearing mice. Data were presented as mean value ± SD of three independent experiments. (D) Blockade of IL-6 by neutralizing antibody inhibited tumor growth in 4T1-RBJ tumor-bearing mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (E) The relative expression of IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) in Gr1+CD11b+ MDSCs cells sorted from peripheral blood, liver, lung, spleen, and tumor tissue derived from 4T1-RBJ-bearing mice compared with 4T1 tumor cells. (F) HE staining and IHC analysis of IL-6R in tumor tissue derived from 4T1-RBJ bearing mice. (G) The mRNA and protein expression of COX2 in Gr1+CD11b+ MDSCs sorted from peripheral blood, liver, lung, spleen, and tumor tissue derived from 4T1-tumor-bearing mice compared with 4T1 tumor cells. **p < 0.01. (H) IL-6-enhanced COX2 expression in MDSCs. MDSCs sorted from tumor tissues were stimulated with IL-6 (100 ng/mL), or pretreated with or without p-Stat3 specific inhibitor (Stattic, 20 µM), and then COX2 expression was detected by real-time PCR and Western blot. **p < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Working model for RBJ-enhanced chronic inflammation promotes tumor progression and metastasis. In response to danger signal, MEK/ERK are activated and then translocated to cell nucleus. In RBJ positive tumor cells (RBJ+/hi), RBJ is located in the nucleus by its own nuclear localization signals, which interacts directly with nuclear presence of MEK, leading to constitutive MEK/ERK activation and resulting in ERK target pro-inflammation gene IL-6 upregulation and IL-6 secretion, which significantly increases persistent recruitment of immunosuppressive MDSCs subsets. Additionally, IL-6 significantly increases COX2 expression in tumor-infiltrating MDSCs. Through these ways, RBJ-enhanced tumor cell production of IL-6 causes chronic inflammation microenvironment in tumor-bearing hosts promoting tumor growth and metastasis.

Discussion

Ras superfamily GTPase is regulatory proteins found in eukaryotic cells involved in a multitude of events, ranging from vesicle traffic to mitogenic activation. This superfamily is further divided in families recognized: Ras, Rho, Arf/Sar, Ran, Rab, and Gem/Kira.29 Mutation or overexpression of Ras superfamily G-protein has been observed in a number of human cancer cases,30 accumulating evidence has showed that Ras oncoprotein can promote proliferation, resist apoptosis, and confer the invasive and metastatic phenotype to tumor cells.26,29,30 Rho family GTPase is thought to be the downstream effector responsible for Ras-induced invasive and metastatic phenotype.31 RhoA regulates stress fiber formation and focal adhesion assembly that results in actomyosin contractility and contraction at the rear of the cell, which leads to translocation of the cell body.32 Rac1 activates actin polymerization through WASP family verprolin-homologous proteins (WAVE) and Arp2/3 complex leading to formation of membrane ruffles that push the cell membrane forward.33,34 Rac-WAVE2 signaling is essential for invasion of B16 melanoma cells in vitro and WAVE2 is involved in metastasis in vivo.35 RBJs are a new family of Ras-related GTP binding proteins that are characterized by the N-terminal GTP-binding domain (small GTPase domain) and the C-terminal J domain.22-25 It has been demonstrated that RBJ was an oncogenic small GTPase required for gastrointestinal cancer tumorigenesis and progression.26 Here, we found that RBJ is overexpressed in most of human and mouse cancer cell lines and in exceeded 50% breast cancer tissues, and higher expression of RBJ in human breast cancer tissue significantly correlates with poorer prognosis in breast cancer patients. Furthermore, forced RBJ expression significantly promotes cancer progression in vitro and in vivo, and accordingly, knockdown of RBJ decreases tumor progression.

Besides tumor cell-initiated autonomous growth, tumor can grow and progress by disrupting the surveillance of host immune system, and escaping from the attack of immune cells.12,36 During this progression, accumulation and activation of MDSCs in tumor microenvironment are tightly associated with tumor progression.13 Increasing evidence show that MDSCs recruitment in cancer patients and tumor-bearing mice are potent suppressors of innate and adaptive immunity and supportive of tumor progression.37,38 Our present data showed that more expansion and accumulation of MDSCs in spleen and tumor tissues were found in RBJ force-expressed 4T1 tumor-bearing mice than that of mice-bearing parental 4T1 cells or 4T1-VB cells. Furthermore, knockdown of RBJ in 4T1 cells reduced MDSCs expansion and recruitment in vitro and in vivo. Tumor-derived soluble factors profoundly affect myelopoiesis and mobilization of myeloid cells as well as their activation. Cytokines are prominent players in chronic inflammation which can mediate tumor initiation, promotion, angiogenesis, and metastasis.39 So, which factor(s) are involved in RBJ-medicated expansion and recruitment of MDSCs? It has been demonstrated that COX2, PGE2, G-CSF, IL-6, and VEGF were involved in MDSCs recruitment and activation. G-CSF can upregulate Bv8 protein in MDSCs, which was found to sustain tumor progression, both by mobilizing MDSCs from bone marrow, and by directly stimulating tumor angiogenesis.40,41 Pro-inflammatory proteins S100A8/A9, PGE2, IL-1β, and IL-6 can promote tumor progression by regulating the accumulation of MDSCs.42 By screening the immunosuppressive and pro-inflammatory factors derived from tumor cells, we found that forced RBJ expression in 4T1 tumor cells significantly increased IL-6 expression and secretion. However, there was no significant increased production of PGE2, G-CSF, VEGF, TGF-β, CXCL1, CXCL2, and M-CSF. In addition, In RBJ+ human BIDC tissues, IHC and IF results showed that RBJ and p-ERK were double positive and co-localization in the nucleus of cancer cells, and inhibition of MEK/ERK activation using signal specific inhibitor markedly reduced IL-6 production, thus suggesting that RBJ-medicated nuclear accumulation and sustained activation of ERK in breast cancer cells contributed to IL-6 production. However, the precise mechanism needs to be further investigation.

Administration of anti-IL-6 neutralizing Ab markedly reduced the chemoattraction of MDSCs in vitro or accumulation in tumor tissues. However, administration of anti-IL-6 neutralizing Ab could not promote MDSCs recruitment in spleen in vivo. Then, we sorted Gr1+CD11b+ MDSCs from tumor tissues, lung, spleen, liver, and peripheral blood of 4T1-RBJ-bearing mice, and detected the expression of IL-6 receptor (IL-6R/CD126) in these sorted MDSCs. The results showed that except MDSCs derived from spleen, the other MDSCs derived from others organ/tissue expressed higher lever IL-6R/CD126, suggesting that RBJ-medicated IL-6 production promoted MDSCs recruitment in a paracrine manner. Additionally, we also found that only in sorted MDSCs derived from tumor tissues expressed higher level COX2, the other MDSCs derived from peripheral blood, spleen, liver, and lung expressed lower or negative lever COX2. Furthermore, exogenous IL-6 could increase COX2 expression both in mRNA and protein lever via, at least partially, STAT3 pathway. Moreover, IL-6 stimulation allows rapid generation of MDSCs from precursors present in mouse and human bone marrow, and MDSCs induced by IL-6+GM-CSF show high tolerogenic activity.43-44 Our data also demonstrated that IL-6 could upregulate COX2 expression in MDSCs, suggesting that IL-6 not only promotes MDSC recruitment, but also regulates MDSC development and functional differentiation. Furthermore, emerging evidence has addressed that higher level of IL-6 is correlated with poor prognosis and associated with tumor growth and metastasis in breast cancer patients. Anti-IL-6/IL-6R/gp130 is a potential therapeutic promising options for the treatment and prevention of breast cancers.45 COX2 in primary breast cancer cells promotes breast cancer bone metastasis, high COX2 expression is associated with advanced stages and is assumed to be a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer.46-48 So, targeting of RBJ in tumor cell may disrupt IL-6 production and then block the immunosuppression, thus inhibiting tumor progression.

In sum, RBJ-mediated nuclear constitutive activation of ERK leads to persistent production of IL-6 by tumor cell, which contributes to MDSCs recruitment and COX2 expression and consequently resulting in promotion of tumor growth and metastasis. RBJ may be a potential target for design of antitumor drug.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate Ms. Miao Chen and Mr. Qiang Wang for their excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research Program of China (2014CB542102) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30972688, 31170844, 31570869).

References

- 1.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002; 420:860-67; PMID:12490959; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature01322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crusz SM, Balkwill FR. Inflammation and cancer: advances and new agents. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015; 2:584-96; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffelt SB, de Visser KE. Cancer: Inflammation lights the way to metastasis. Nature 2014; 507:48-9; PMID:24572360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15:e493-e503; PMID:25281468; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol 2009; 182:4499-506; PMID:19342621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi S, Baghdadi M, Tsuchikawa T, Wada H, Nakamura T, Abe H, Nakanishi S, Usui Y, Higuchi K, Takahashi M et al.. Chemotherapy-derived inflammatory responses accelerate the formation of immunosuppressive myeloid cells in the tissue microenvironment of human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 2015; 75:2629-40; PMID:25952647; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, Fingleton B, Green-Jarvis B, Shyr Y, Matrisian LM, Carbone DP, Lin PC. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 2004; 6:409-21; PMID:15488763; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu P, Wu D, Ni C, Ye J, Chen W, Hu G, Wang Z, Wang C, Zhang Z, Xia W et al.. γδT17 cells promote the accumulation and expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in human colorectal cancer. Immunity 2014; 40:785-800; PMID:24816404; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markowitz J, Wesolowski R, Papenfuss T, Brooks TR, Carson WE. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 140:13-21; PMID:23828498; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-013-2618-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz-Montero CM, Finke J, Montero AJ. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: therapeutic, predictive, and prognostic implications. Semin Oncol 2014; 41:174-84; PMID:24787291; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Draghiciu O, Lubbers J, Nijman HW, Daemen T. Myeloid derived suppressor cells-An overview of combat strategies to increase immunotherapy efficacy. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4:e954829; PMID:25949858; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/21624011.2014.954829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao X. Integrative strategy for improving cancer immunotherapy. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016; 5:485-87; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00109-016-1424-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Cao X. Immunosuppressive cells in tumor immune escape and metastasis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016; 5:509-22; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00109-015-1376-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rambaldi A, Wakamiya N, Vellenga E, Horiguchi J, Warren MK, Kufe D, Griffin JD. Expression of the macrophage colony-stimulating factor and c-fms genes in human acute myeloblastic leukemia cells. J Clin Invest 1988; 81:1030-35; PMID:2832442; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI113413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka J, Miyake T, Shimizu T, Wakayama T, Tsumori M, Koshimura K, Murakami Y, Kato Y. Effect of continuous subcutaneous administration of a low dose of G-CSF on stem cell mobilization in healthy donors: a feasibility study. Int J Hematol 2002; 75:489-92; PMID:12095148; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02982111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrams SI, Waight JD. Identification of a G-CSF-Granulocytic MDSC axis that promotes tumor progression. Oncoimmunology 2012; 1:550-1; PMID:22754783; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/onci.19334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chafe SC, Lou Y, Sceneay J, Vallejo M, Hamilton MJ, McDonald PC, Bennewith KL, Möller A, Dedhar S. Carbonic anhydrase IX promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell mobilization and establishment of a metastatic niche by stimulating G-CSF production. Cancer Res 2015; 75:996-1008; PMID:25623234; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melani C, Chiodoni C, Forni G, Colombo MP. Myeloid cell expansion elicited by the progression of spontaneous mammary carcinomas in c-erbB-2 transgenic BALB/c mice suppresses immune reactivity. Blood 2003; 102:2138-45; PMID:12750171; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunt SK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Inflammation induces myeloid-derived suppressor cells that facilitate tumor progression. J Immunol 2006; 176:284-90; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha P, Clements VK, Fulton AM, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Prostaglandin E2 promotes tumor progression by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res 2007; 67:4507-13; PMID:17483367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taniguchi K, Karin M. IL-6 and related cytokines as the critical lynchpins between inflammation and cancer. Semin Immunol 2014; 26:54-74; PMID:24552665; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nepomuceno-Silva JL, de Melo LD, Mendonçã SM, Paixão JC, Lopes UG. RBJs: a new family of Ras-related GTP-binding proteins. Gene 2004; 327:221-32; PMID:14980719; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gene.2003.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nepomuceno-Silva JL, De Melo LD, Mendonça SM, Paixão JC, Lopes UG. Characterization of Trypanosoma cruzi TcRBJ locus and analysis of its transcript. Parasitology 2004; 129:325-33; PMID:15471007; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S0031182004005621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elias M, Archibald JM. The RBJ family of small GTPases is an ancient eukaryotic invention probably functionally associated with the flagellar apparatus. Gene 2009; 442:63-72; PMID:19393304; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gene.2009.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos Dos GR, Nepomuceno-Silva JL, de Melo LD, Meyer-Fernandes JR, Salmon D, Azevedo-Pereira RL, Lopes UG. The GTPase TcRjl of the human pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi is involved in the cell growth and differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2012; 419:38-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen T, Yang M, Yu Z, Tang S, Wang C, Zhu X, Guo J, Li N, Zhang W, Hou J et al.. Small GTPase RBJ mediates nuclear entrapment of MEK1/MEK2 in tumor progression. Cancer Cell 2014; 25:682-96; PMID:24746703; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Q, Tan Q, Chen K, Zheng Y, Wang Q, Cao X. Blockade of Fas signaling in breast cancer cells suppresses tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting Fas signaling-initiated cancer-related inflammation. J Biol Chem 2014; 289:11522-35; PMID:24627480; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.525014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Zhang Y, Liu Q, Zhang M, Yu Y, Liu X, Cao X. Fas signal promotes lung cancer growth by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells via cancer cell-derived PGE2. J Immunol 2009; 182:3801-8; PMID:19265159; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0801548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takai Y, Sasaki T, Matozaki T. Small GTP-binding proteins. Physiol. Rev 2001; 81:153-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tetlow AL, Tamanoi F. The Ras superfamily G-proteins. Enzymes 2013; 33:1-14; PMID:25033798; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-416749-0.00001-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahai E, Marshall CJ. RHO-GTPases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2:133-42; PMID:12635176; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Burridge K. Rho-stimulated contractility drives the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions. J Cell Biol 1996; 133:1403-15; PMID:8682874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takenawa T, Miki H. WASP and WAVE family proteins: key molecules for rapid rearrangement of cortical actin filaments and cell movement. J Cell Sci 2001; 114:1801-9; PMID:11329366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suetsugu S, Miki H, Takenawa T. Spatial and temporal regulation of actin polymerization for cytoskeleton formation through Arp2/3 complex and WASP/WAVE proteins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2002; 51:113-22; PMID:11921168; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cm.10020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurisu S, Suetsugu S, Yamazaki D, Yamaguchi H, Takenawa T. Rac-WAVE2 signaling is involved in the invasive and metastatic phenotypes of murine melanoma cells. Oncogene 2005; 24:1309-19; PMID:15608687; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1208177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma Y, Yang H, Pitt JM, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Therapy-induced microenvironmental changes in cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016; 5:497-508; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00109-016-1401-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Görgün GT, Whitehill G, Anderson JL, Hideshima T, Maguire C, Laubach J, Raje N, Munshi NC, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Tumor-promoting immune-suppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the multiple myeloma microenvironment in humans. Blood 2013; 121:2975-87; PMID:23321256; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2012-08-448548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9:162-74; PMID:19197294; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esquivel-Velázquez M, Ostoa-Saloma P, Palacios-Arreola MI, Nava-Castro KE, Castro JI, Morales-Montor J. The role of cytokines in breast cancer development and progression. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2015; 35:1-16; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/jir.2014.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serafini P, Carbley R, Noonan KA, Tan G, Bronte V, Borrello I. High-dose granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Res 2004; 64:6337-43; PMID:15342423; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shojaei F, Wu X, Zhong C, Yu L, Liang XH, Yao J, Blanchard D, Bais C, Peale FV, van Bruggen N et al.. Bv8 regulates myeloid-cell-dependent tumour angiogenesis. Nature 2007; 450:825-31; PMID:18064003; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinha P, Okoro C, Foell D, Freeze HH, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Srikrishna G. Proinflammatory S100 proteins regulate the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol 2008; 181:4666-75; PMID:18802069; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y, Wu T, Shao S, Shi B2, Zhao Y. Phenotype, development, and biological function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology 2015; 5:e1004983; PMID:27057424; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1004983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, Mesa C, Fernandez A, Dolcetti L, Ugel S, Sonda N, Bicciato S, Falisi E et al.. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity 2010; 32:790-802; PMID:20605485; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Casneuf T, Axel AE, King P, Alvarez JD, Werbeck JL, Verhulst T, Verstraeten K, Hall BM, Sasser AK. Interleukin-6 is a potential therapeutic target in interleukin-6 dependent, estrogen receptor-α-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2016; 8:13-27; PMID:26893580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucci A, Krishnamurthy S, Singh B, Bedrosian I, Meric-Bernstam F, Reuben J, Broglio K, Mosalpuria K, Lodhi A, Vincent L et al.. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in primary breast cancers predicts dissemination of cancer cells to the bone marrow. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009; 117:61-8; PMID:18663571; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-008-0135-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karavitis J, Zhang M. COX2 regulation of breast cancer bone metastasis. Oncoimmunology 2013; 2:e23129; PMID:23802065; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/onci.23129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elzagheid A, Emaetig F, Alkikhia L, Buhmeida A, Syrjänen K, El-Faitori O, Latto M, Collan Y, Pyrhönen S. High cyclooxygenase-2 expression is associated with advanced stages in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 2013; 33:3137-43; PMID:23898071 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]