ABSTRACT

Our previous studies showed that non-immunogenic H-2d tumor cells of distinct epithelial histotypes can become highly immunogenic, induce a protective CD4+ T cell response and vaccinate the animals against parental MHC-II-negative cells if they are rendered MHC class II-positive by stable transfection with the Air-1-encoded MHC-II transcriptional activator CIITA.

These studies did not establish, however, whether tumor immunity was the consequence of a direct priming of naive CD4+ T lymphocytes by CIITA-driven MHC-II-expressing tumor cells or by MHC-II-tumor antigen complexes engulfed by dendritic cells (DC) and exposed on the surface of these professional antigen presenting cells (APC). In the present investigation, we provide definitive evidence that CIITA-tumor cells are the crucial APC in vivo for CD4+ T cell priming. By using a transgenic H-2b mouse model, the CD11c.DTR C57BL/6 mice, in which DC can be functionally deleted by administration of diphteria toxin, we show that CIITA-tumor cells of two distinct histotypes can be rejected or strongly retarded in their growth in DC-deleted mice. To rule out that in absence of DC, other professional APC could prime naive CD4+ T cells, we deleted the macrophages in CD11c.DTR C57BL/6 mice by administration of liposome Clodronate and still obtained rejection or strong retardation in tumor growth of CIITA-tumor cells. Our results challenge the diffuse belief that non-professional APC cannot efficiently prime naive T cells in vivo. Moreover, the demonstration of the general validity of our approach in different genetic backgrounds may open a way for new strategies of antitumor treatment in clinical settings.

KEYWORDS: CD4+ T cells, CIITA, DC, MHC class II

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen presenting cells

- CIITA

class II transactivator

- DC

dendritic cells

- DT

diphteria toxin

- DTR

diphteria toxin receptor

- LClo

liposome Clodronate

- TAA

tumor-associated antigens

Introduction

The onset, expansion, persistence and spreading of tumors are under the control of a complex series of events that encompass intrinsic modifications of cancer cells mostly impacting on the homeostasis of the cell cycle. Among these, mutations in proto-oncogenes and in tumor suppressor genes and alteration of the apoptotic process play a crucial role.1 More recently, it became apparent that extrinsic mechanisms, related to the capacity of the host to counteract tumor growth, may impact on the final outcome of the neoplastic process.2 As far as host mechanisms counteracting the tumor, a key function is played by the immune system. Both innate and adaptive immunity have been shown to participate to this response.2 Nevertheless the fact that the tumor process takes off in cancer patients demonstrates that the recognition of cancer cells and/or the equilibrium between tumor growth and antitumor immune response can be altered, favoring the progression of the malignancy.3,4 A crucial aspect of the immune response against the tumor is the initial recognition of tumor-associated antigens (TAA) by CD4+ T helper cells (TH)5 that notice TAA presented within the context of MHC class II (MHC-II) molecules expressed on professional antigen presenting cells (APC) mainly represented by dendritic cells (DC).6,7 TH cells are fundamental for optimal induction of both humoral and cellular effector mechanisms,8 particularly for the maturation of MHC class I-restricted CD8+ naive T cells, their clonal expansions and acquisition of cytolytic function.9 The latter function is of relevance in the context of antitumor immunity since CD8+ cytolytic T cells (CTL) are believed to be the major lymphocyte effectors against cancer cells.10

In the attempt to generate an effective and long-lasting adaptive immune response against the tumor, we have undertaken since several years an approach whereby tumor cells are genetically modified to express MHC-II molecules with the idea that they may operationally function as surrogate APC for presentation of their TAA to TH cells. The constitutive MHC-II expression on MHC-II-negative tumor cells was induced by transfection with the AIR-1-encoded transcriptional activator CIITA, the major factor governing the expression of MHC-II genes. In tumor cells of the H-2d genetic background, expressing both IA and IE molecules, this approach has proven to be particularly successful since we could demonstrate that highly tumorigenic cells of both epithelial and connective tissue origin (carcinomas and sarcomas), rendered MHC-II-positive upon CIITA transfection, not only could be rejected or strongly delayed in their growth when injected in syngeneic immunocompetent recipients (Balb/C mice), but also could stimulate an anamnestic response capable to induce rejection of parental untransfected, MHC-II-negative cells.11-14 Importantly, protective immunity could be transferred to naïve syngeneic Balb/C mice by injecting CD4+ TH cells from mice “vaccinated” with CIITA-transfected tumor cells.13,14 All together, our previous results indicated that MHC-II molecules expressed in tumor cells were necessary to induce a potent adaptive immune response against the tumor in vivo, that this response was mastered by CD4+ TH cells,15 and importantly could re-direct the tumor microenvironment from a pro-tumor to an antitumor milieu.16 Although highly suggestive, these results did not definitively establish that CIITA-expressing tumor cells were indeed the crucial APC capable to prime in vivo naive TH cells to become tumor-specific TH cells. In addition, it was not known whether CIITA-driven MHC-II expression could render immunogenic tumor cells of a different genetic background, particularly those with an H-2b MHC in which only IA molecules are expressed because of a defect of the Eα gene.17 This study was set to investigate the above crucial questions and thus to definitively substantiate the capacity of CIITA-driven MHC-II-positive tumor cells to prime in vivo naive CD4+ T cells. To this end, we took advantage of a recently described transgenic mouse model, the CD11c.DTR C57BL/6 mice with an H-2b background, expressing the diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) under the control of the promoter of CD11c gene highly expressed in dendritic cells (DC). In this system, DC, believed to be the crucial cells for T-cell priming, can be depleted in vivo by injecting the mice with DT,18 offering the possibility to study an antitumor immune response in the absence of this crucial APC population. Our results indicate that CIITA-driven MHC-II-positive tumor cells of the H-2b genetic background can indeed recapitulate the results already obtained in the H-2d genetic background, even if only one MHC-II molecule is expressed. Importantly, these MHC-II IA-only positive tumor cells can prime naive CD4+ TH cells in vivo in the absence of DC and induce a CD4+ TH cell antitumor response that can be transferred to naive syngeneic recipients. The demonstration of general validity of our approach may open the way for new strategies for antitumor treatment in clinical settings. Moreover, our results challenge the diffuse belief that non-professional APC cannot efficiently prime naive T cells in vivo.

Results

CIITA-driven H-2b IA+ tumor cells trigger specific long-lasting antitumor immune response

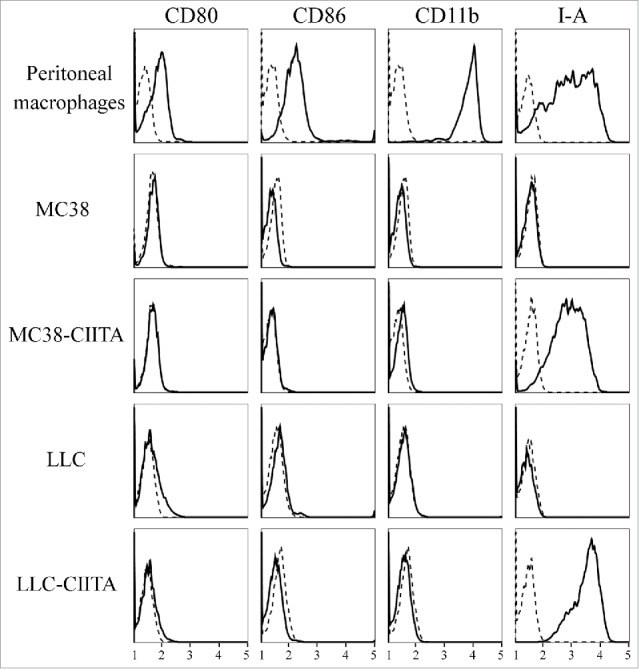

The MC38 colon carcinoma and the LLC Lewis Lung Carcinoma tumor cell lines were stably transfected with CIITA. As previously demonstrated in the tumor cell lines of Balb/C origin displaying an H-2d genotype,11,14 also the H-2b MHC-II-negative MC38 and LLC cell lines, upon CIITA transfection, displayed a stable MHC-II IA-positive phenotype, as assessed by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence (Fig. 1). Importantly, the CIITA-driven MHC-II de novo expression was not accompanied by a similar de novo expression of other relevant markers, such as CD80 and CD86, involved as co-stimulatory molecules in the MHC-II-restricted antigen presentation to TH cells (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Lack of the expression of CD80 and CD86 co-stimulatory molecules on both parental and CIITA transfected tumor cells. The expression of CD80 and CD86 co-stimulatory molecules (first two rows of vertical panels) was assessed on parental MC38 and LLC and their corresponding stably CIITA-transfected tumor cells by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence with specific antibodies. The cells were also assessed for the expression of CD11b and MHC-II IA markers (third and fourth rows of vertical panels, respectively). As positive control for the expression of the four markers, a population of activated peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6 mice was analyzed. Results are expressed as number of cells (ordinate) versus the intensity of fluorescence in arbitrary units (abscissa). In each histogram, negative controls, obtained by staining the cells with an isotype-matched antibody, are depicted as dashed lines.

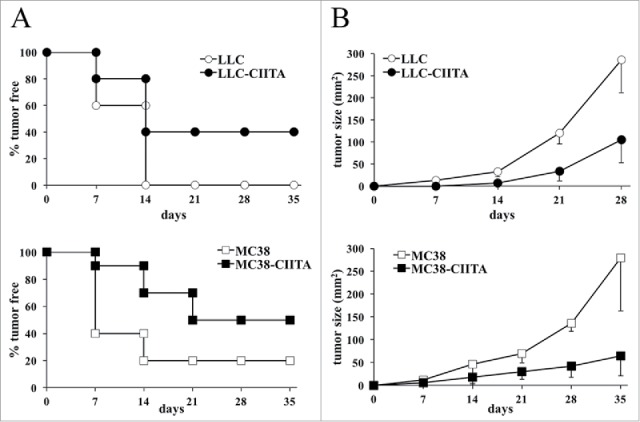

CIITA-transfected tumor cells were injected into naive syngeneic C57BL/6 mice and tumor growth was monitored over time. Both MC38-CIITA and LLC-CIITA tumor cells were either strongly retarded in their in vivo growth or even rejected in a significant proportion of mice with respect to their parental tumor counterpart (MC38 and LLC; Fig. 2). Indeed, after 5 weeks, 40% and 50% of mice injected with LLC-CIITA and MC38-CIITA, respectively, did not develop any tumor (Fig. 2A), whereas those that developed tumors displayed a growth kinetics 4- to 5-fold reduced as compared with their parental tumor counterpart (Fig. 2B)

Figure 2.

CIITA-transfected H-2Kb tumors are either completely rejected or show a significant growth retardation in vivo. Equal numbers (5 × 104) of parental MC38, parental LLC, MC38-CIITA, or LLC-CIITA tumor cells were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in 7–9-weeks-old C57BL/6 female mice (at least five mice per group). Tumors growth along with the overall health condition of the mice was checked at least twice per week. (A) The percentage of tumor-free mice in both groups (ordinate) is presented as a function of time in days (abscissa). (B) The average size of tumors growing in each group is presented in mm2 (ordinate) as a function of time in days (abscissa). The data collected were from at least two experiments. Open symbols refer to parental tumor cells; full symbols refer to CIITA-transfected tumor cells. Differences between both groups in the graphs of average tumor size kinetics were significant (p value < 0.01) at all time points.

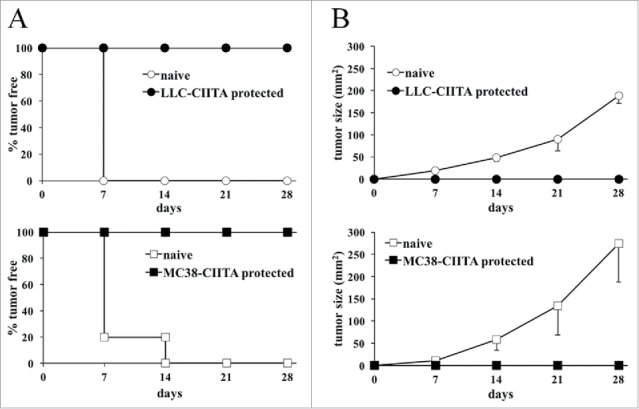

To investigate whether the rejection and/or the growth retardation of CIITA-tumors in H-2b C57BL/6 was attributable to the generation of an adaptive immune response that could protect the mice from a challenge with untransfected parental tumors, MC38-CIITA and LLC-CIITA vaccinated mice that did not develop tumors after 4 weeks from injection were challenged with the corresponding untransfected parental cells. Importantly, the challenge with parental cells was performed by using 4-fold the number of cells (2 × 105) originally injected to assess tumor take. Results clearly show that animals immunized and protected from CIITA-tumors in both experimental systems fully rejected, in 100% of the cases, the untransfected MHC-II-negative parental tumors (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Mice vaccinated with CIITA-transfected tumors are resistant to challenge with parental tumors. Mice resistant to LLC-CIITA (LLC-CIITA protected) or MC38-CIITA (MC38-CIITA protected) tumor cell growth or naive control mice were challenged with 2 × 105 parental tumor cells. (A) The percentage of tumor-free mice in the various groups is presented in the ordinate as a function of time in days after injection (abscissa). (B) The average size in mm2 of the tumors growing in each group is presented in the ordinate as a function of time in days after injection (abscissa). One hundred percent of the challenged mice rejected parental tumor cells indicating that CIITA-tumor vaccination induced long-lasting resistance also to MHC class II-negative parental tumor cells. Differences between both groups in the graphs of average tumor size kinetics were highly significant (p value < 0.001) at all time points.

From these results, we conclude that tumor cells of two distinct histotype origins with an H2-b genetic background and strongly tumorigenic in vivo not only can be rejected or strongly delayed in their growth after de novo expression of CIITA-mediated MHC-II IA molecules but also induce an immunological memory capable to confer resistance to challenge with MHC-II-negative parental tumors.

CD4+ TH cells are the key antitumor lymphocytes elicited by CIITA-driven MHC-II-expressing tumor cells

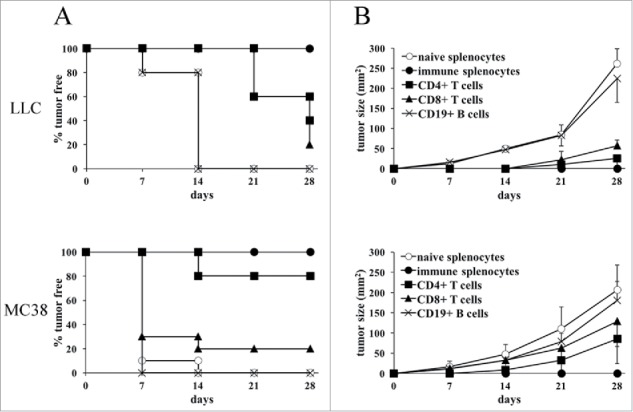

In order to define the immune cell subpopulation(s) responsible for the triggering and the maintenance of the protective antitumor state after vaccination with CIITA-transfected tumor cells, experiments of adoptive cell transfer (ACT) were performed. Total spleen cells, purified CD4+, CD8+ and B cells derived from mice that had rejected MC38-CIITA or LLC-CIITA and a challenge with corresponding parental untransfected cells, were co-injected with 2 × 105 parental tumor cells into naive C57BL/6 recipients. The ratio of tumor cell versus total splenocytes, CD4+, CD8+ and B cells was 1:50, 1:15, 1:10, and 1:25, respectively, to mimic the relative proportion of the various lymphocytes subpopulations present in the spleen. Tumor growth in the distinct groups of mice was followed for 4 weeks. Total immune spleen cells were able to protect 100% of the mice from parental tumor take in both MC38 and LLC injected animals (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, CD4+ lymphocytes were the most potent protective lymphocyte subpopulation since 80% of MC38-injected mice did not develop the tumor after 4 weeks (Fig. 4A), and those developing the tumor showed a strongly retarded kinetics of tumor growth (Fig. 4B). Similarly, 60% of LLC co-injected mice had no sign of tumor growth after 3 weeks (Fig. 4A); after 4 weeks, 40% of the animals remained tumor-free and upon tumor development, the tumors were strongly retarded in their growth (Fig. 4B). On the contrary, CD8+ lymphocytes were able to fully protect from tumor growth only 20% of the MC38- and LLC-injected mice (Fig. 4A). Nevertheless, in both MC38- and LLC-injected mice, CD8+ cells from immune mice were able to significantly delay tumor growth (Fig. 4B). Neither protection from tumor take nor retardation of tumor growth was observed in both MC38- and LLC-injected mice when co-injected with CD19+ B lymphocytes from immune mice. As expected, spleen cells from naive mice, used as negative control, were not protective.

Figure 4.

CD4+ Th cells are the key cells responsible for the antitumor immunity induced after LLC-CIITA or MC38-CIITA vaccination. Spleens from protected mice were isolated and processed to purify CD4+, CD8+ T cells and B cells. Naive mice were co-injected s.c. with 2 × 105 MC38 or LLC parental cells together with either immune total splenocytes, purified CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD19+)B cells or with total naive splenocytes, as a control. (A) The percentage of tumor-free mice in each group is presented in the ordinate as a function of time in days after co-injection (abscissa). (B) The average size in mm2 of tumors growing is presented in the ordinate as a function of time in days after co-injection (abscissa). No statistical significance was observed in the growth of tumors after adoptive cell transfer of naïve splenocyte and immune CD19+ B cells in both LLC and MC38 groups. Statistical significance was observed between naïve splenocytes or CD19+ B cells and immune splenocytes (p value < 0.01), CD4+ T cells (p value < 0.01), CD8+ T cells (p value < 0.01) at all time points for LLC; between naive splenocytes or CD19+ B cells and immune splenocytes (p value < 0.01) and CD4+ T cells (p value < 0.01) at all time points, and with CD8+ T cells (p value < 0.01) after 21 d, for MC38.

From these results, we conclude that, similarly to the H-2d Balb/C system, even tumors of the H-2b genetic background stimulate a protective adaptive immune response when rendered MHC-II-positive upon transfection with CIITA and that this immune response is dominated by the triggering of CD4+ TH cells and to much lesser extent by CD8+ T cells.

CIITA-driven H-2b IA+ tumor cells act as surrogate APC for in vivo priming

Having established that CIITA-driven MHC-II+ tumor cells can efficiently trigger a protective adaptive immune response also in the H-2b genetic background and that the protection can be efficiently transferred by immune CD4+ TH cells, we next performed experiments to assess whether the triggering of naive CD4+ T cells in vivo and therefore the initial antigen presentation was operated directly by the MHC-II+ tumor cells or via the intervention of DC, the primary cell subpopulation responsible of the MHC-II-restricted antigen presentation to and priming of naive CD4+ T cells.7 We took advantage of the availability of CD11c.DTR transgenic mice constructed in the H-2b genetic background which express the DTR under the control of the CD11c promoter mainly expressed in DC. Thus, DC of CD11c.DTR transgenic mice can be efficiently deleted for several weeks after treatment with diphtheria toxin (DT).18

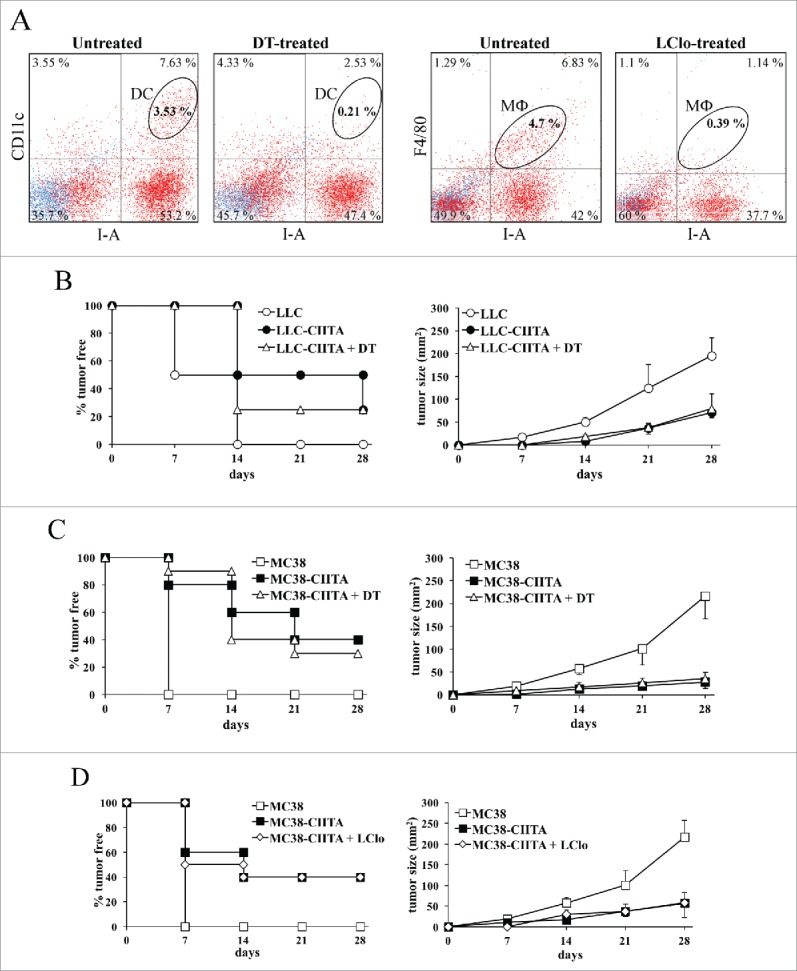

CD11c.DTR transgenic mice, periodically injected with DT as described in section Materials and Methods, were injected with LLC-CIITA or MC38-CIITA and the kinetics of tumor take and tumor growth was followed over time. DC depletion in tumor-injected mice was assessed as originally described18 by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence of spleen cells co-stained with anti-CD11c and anti-MHC IA antibodies since the most prominent DC population displaying APC activity expresses both these markers. Indeed, DT treatment of CD11c.DTR transgenic mice was able to virtually deplete the entire DC population from the spleen (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

CIITA-driven MHC-II-positive tumors are the main APC in vivo. (A) CD11c.DTR transgenic mice were treated with diphteria toxin (DT), or with liposomal Clodronate (LClo) as described in section Materials and Methods. DC depletion was checked after 3 d from the first DT injection by immunofluorescence and FACS analysis on spleen cells co-stained with anti-CD11c and anti-MHC IA directly labeled monoclonal antibodies and compared with the one in untreated mice (second and first dot histogram, respectively). Macrophage deletion was checked on the following day after the second Clodronate injection by immunofluorescence and FACS analysis on spleen cells co-stained with anti-macrophage F4/80 and anti-MHC IA directly labeled monoclonal antibodies and compared with the one in untreated mice (fourth and third dot histogram, respectively). (B) Equal numbers (5 × 104) of LLC-CIITA tumor cells were injected in either untreated (LLC-CIITA) or DT-treated (LLC-CIITA + DT) CD11c.DTR transgenic mice. A group of untreated mice were also injected with the same number of parental LLC cells, as control. Tumor take, measured as percentage of mice with tumors (ordinate, left panel) and kinetics of tumor growth (ordinate, right panel) were followed over time (days in abscissa). (C) The same protocol described in (B) was also performed for MC38-CIITA and their corresponding MC38 parental cells. (D) CD11c.DTR transgenic mice were treated with liposome Clodronate (LClo) as described in section Materials and Methods, and injected with 5 × 104 MC38-CIITA tumor cells (MC38-CIITA + LClo). As control, untreated mice were injected with equal numbers of either MC38-CIITA or parental MC38 tumor cells. Tumor take, measured as percentage of mice with tumors (ordinate, left panel) and kinetics of tumor growth (ordinate, right panel) were followed over time (days in abscissa). In panels B–D, differences in tumor growth kinetics between untransfected parental cells (LLC or MC38) and CIITA-transfected or CIITA-transfected + treated (DT and LClo) were significant at all time points considered (p value < 0.01).

After DC depletion, 20% of mice injected with LLC-CIITA were still able to fully reject the tumor after 4 weeks. Tumor take was delayed in LLC-CIITA injected mice that did not receive the DC depletion regimen, although at 4 weeks also these animals showed the same percentage of tumor take as the DC-depleted mice (Fig. 5B, left panel). Most importantly, LLC-CIITA tumors showed a marked reduction in their growth kinetics that was superimposable to the one obtained in mice that were not treated with DT (Fig. 5B, right panel). Similarly, after DC depletion, 35% of mice injected with MC38-CIITA tumor cells fully rejected the tumor after 4 weeks from tumor cell injection. This proportion was similar to the one obtained in mice not undergoing DC depletion (40%; Fig. 5C, left panel). Again, and of relevance, even in the MC38-CIITA tumor model, tumors that were developed in DC-depleted mice displayed a significant retardation in their growth and a strong reduction in their volume. This growth kinetics was indeed superimposable to that obtained in DT-untreated mice without DC depletion (Fig. 5C, right panel).

From these results, we conclude that CIITA-tumor cells can still induce a potent immune response in vivo and thus prime CD4+ T cells even in the absence of the key APC population.

In order to exclude the possibility that in the absence of DC other professional APC, such as macrophages, can provide specific tumor antigen priming for naive CD4+ T cells in our experimental model, CD11c.DTR transgenic mice were treated with liposomal Clodronate (LClo), a chemical compound that has been shown to induce a substantial in vivo depletion of macrophages.19 Macrophage depletion in tumor-injected mice was assessed by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence of spleen cells co-stained with anti-F4/80 antibody, specific for macrophages, and antibody for MHC IA, also expressed in macrophages. Clodronate treatment of CD11c.DTR transgenic mice was able to virtually deplete the macrophage population in the spleen (Fig. 5A, compare third and fourth panels). LClo-treated mice were injected with MC38-CIITA tumor cells and in vivo tumor growth was evaluated over time. After 4 weeks, 40% of animals were able to reject MC38-CIITA tumor cells completely, exactly the same proportion rejecting the tumor cells in control animals not treated with LClo (Fig. 5D, right panel). Again, even in the case of LClo-treated animals, the kinetics of MC38-CIITA tumor growth in 60% of animals that did not reject the tumor was strongly retarded as compared with the one of parental tumors and closely followed the kinetics of MC38-CIITA tumors growing in animals that did not undergo LClo treatment (Fig. 5D, right panel).

Taken together, the results presented in this section indicate that CIITA-tumor cells are indeed the major, if not the exclusive, antigen presenting cells for priming CD4+ naive T cells in vivo.

Discussion

Our previous studies have demonstrated that CIITA-driven MHC-II gene expression in tumor cells of the H-2d genetic background can indeed render these cells potent stimulators of a protective and long-lasting adaptive antitumor immune response capable to protect the syngeneic vaccinated animals against a challenge with MHC-II-negative parental tumors and to transfer this protection to naive recipient by MHC-II-restricted CD4+ TH cells.11-14 In this study, we extended this observation to tumor cells of the H-2b genetic background, which at variance with H-2d genotype can express only one of the two MHC-II molecules, the IA but not the IE molecule. Two distinct MHC-II-negative tumor cell lines, the MC38 colon carcinoma and the LLC Lewis lung carcinoma, highly tumorigenic in vivo, became strongly immunogenic after de novo expression of MHC-II molecules mediated by CIITA transfection. Although we could not reach the percentage of full rejection of certain Balb/C tumor cell lines such as the TS/A mammary carcinoma or the WEHI 164 fibrosarcoma,11,14 up to 50% and 40% of animals were able to reject MC38-CIITA and LLC-CIITA tumor cells, respectively. Importantly, however, the remaining animals that did not reject the tumor developed an immune response capable to significantly reduce tumor growth, indicating that all animals were indeed responding against the tumor. The reason of absence of full rejection in the second group of mice is most likely related to the possible in vivo modulation of MHC-II expression in the injected tumor cells, as we previously observed.11,12 Importantly, all rejecting animals were resistant to challenge with parental MHC-II-negative tumors and their CD4+ TH cells could transfer protection to naive H-2b C57Bl/6 mice. These results definitively establish the general validity of our approach and demonstrate that tumor cells of distinct genetic background and distinct histotype origin can become immunogenic when expressing CIITA-driven MHC-II molecules. Importantly, the present results indicate that a single MHC-II-restricting element, the IA molecule, could bind sufficient tumor-associated antigens to mediate CD4+ TH cell recognition and triggering of adaptive antitumor responses in vivo.

Although we have previously clearly demonstrated that the MHC-II molecules of tumor cell origin were necessary to mediate the triggering process of the key lymphocytes initiating and maintaining the antitumor state, that is the CD4+ TH cells, we could not firmly establish whether the CIITA-tumor cells were indeed themselves the prominent APC capable to perform in vivo priming of naive TH cells. Indeed, the possibility existed that, upon injection, MHC-II-TAA complexes derived from dying cells or from cell debris could be captured by DC and used by these professional APC to trigger and prime naive CD4+ TH cells. This crucial point was addressed in this study by the use of the CD11c.DTR transgenic mice, constructed in a C57BL/6 H-2b background, expressing the DTR under the control of the CD11c promoter, mainly expressed in DC. In these mice, DC could be conditionally deleted by treatment with DT.18 Our results clearly demonstrate that both MC38-CIITA and LLC-CIITA tumors cells can still be rejected or strongly delayed in their growth in DT-treated CD11c.DTR transgenic mice in a way very similar to that obtained in untreated counterpart or in non-transgenic C57BL/6 mice. Moreover, although it has been reported that DT treatment of CD11c.DTR transgenic mice may also partially ablate macrophages,20,21 the other important professional APC in vivo, we treated CD11c.DTR transgenic mice with LClo, a compound that upon selective phagocytosis by macrophages kills the cells by apoptosis,19 and in the spleen ablates particularly the marginal zone macrophages and metallophilic macrophages, considered the predominant APCs, in the spleen.22

Again, upon injection, CIITA-tumor cells could be rejected or strongly retarded in their growth with superimposable behavior as the one observed in liposomal-untreated mice. Thus, CIITA-driven MHC-II-positive tumor cells can perform not only antigen processing and presenting function in vitro12,23 but they can also serve as surrogate APC in vivo to prime naive CD4+ TH cells and induce potent adaptive immune response against the tumor.

Our results challenge the widely accepted view that antigen priming of naive tumor-specific CD4+ TH cells in vivo can be optimally performed only by professional APC and particularly by DC.24 This view has been supported by the notion that optimal stimulation of naive TH cells requires two signals, the first provided by the antigen-specific T-cell receptor recognizing MHC-II-antigenic peptide complex, and the second provided by the CD28 molecule interacting with co-stimulatory molecules such as the B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86) optimally expressed on DC.25 Even if tumor cell may express in certain cases MHC-II molecules, they do not express in general co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86 and thus they cannot provide the second signal. MC38 and LLC tumor cells used in this study do not express CD80 and CD86 co-stimulatory molecules and this phenotype is not modified by CIITA transfection (Fig. 1). Yet, the absence of co-stimulatory molecules does not prevent CIITA-driven MHC-II-expressing tumor to act as potent surrogate APC in vivo. Thus, either CIITA-tumors do not need accessory molecules to perform their APC function in vivo, or other accessory molecules are involved to provide the second signal. Future investigation will be focused on this important issue.

Another important consideration that stems from our studies relates to the anatomical location at which CIITA-tumor cells' APC function takes place. It is widely accepted that priming of antigen-specific naive CD4+ T cells by professional APC takes place in secondary lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes and spleen. There, DC that have captured and processed the antigens in the periphery migrate and present antigenic peptides within the context of MHC-II molecules.7 However, previous studies of our group have shown that, in contrast to parental tumors where leukocyte infiltrate is scanty, CIITA-tumors rapidly become infiltrated first by CD4+ T cells and subsequently by other cells such as DC, CD8+ T cells and macrophages,12 thus, reorienting the tumor microenvironment from a pro-tumor to an antitumor microenvironment.16 Moreover, it has been shown that lymphocytes can organize themselves in lymphoid tissues different from classical lymph nodes, the so-called tertiary lymphoid organs or ectopic lymphoid-like structures, peculiar lymphoid formations found in inflamed and, interestingly, in tumoral tissues.26 They show many characteristics of lymph nodes associated with the generation of an adaptive immune response.27 Thus, it is tempting to speculate that tumor cells endowed with CIITA-driven MHC-II expression not only may exert full APC function for priming naive tumor-specific CD4+ T cells but may also perform this activity within the tumor tissue itself where a rudiment of organized lymphoid structure can be generated.

Finally, considering the high in vivo immunogenicity of CIITA-driven MHC-II-expressing tumors, it is clear that these tumor cells optimally express the relevant MHC-II-TAA complexes and key neoantigens for immune stimulation. These cells therefore may be instrumental to purify and sequence the key TAA that in conjunction with similarly derived HLA-class I-restricted TAA peptides will be the basis for the construction of a multi-peptide, multi-epitope vaccine that can target both CD4+ TH and CD8+ CTL antitumor responses.

Materials and methods

Transfection and phenotypic analysis of tumor models

MC38, colon carcinoma, and LLC, Lewis Lung carcinoma, of C57BL/6 H-2b haplotype were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium, DMEM, with 4.5 g/L Glucose, L-Glutamine and supplemented with 10% of heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Lonza BioWhittaker™, Catalog number: BE12-604F)

The full-length human CIITA cDNA obtained as previously described28 was inserted into the Xho-I site of the pLXIN retroviral vector (Clontech, Catalog number 63150). DNA transfections were performed using FuGENE™ HD Transfection Reagent (Promega™ Catalog number: E2312), following the manufacturer's instructions with a 1:3 ratio of microgram DNA: microgram of Transfection Reagent respectively. The two tumor cell lines were also transfected with pLXIN empty vector as controls.

The expression of different immune markers was assessed on the surface of the transfected and parental cell lines by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry (BD FACSAria™ II Cell Sorter, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA 95131 USA) using the following antibodies: M1/42 anti-H2 (BioLegend®, Catalog number: 125508), M5/114.15.2 anti-IA/IE (Biolegend®, Catalog number: 107626), 16–10A1 anti-CD80 (BioLegend®, Catalog number: 104705), GL1 anti-CD86 (Becton Dickinson, Catalog number: 558703) and M1/70 anti CD11b (Affymetrix eBioscience, Catalog number: 17-0112-82)

Vaccination and challenge

C57BL/6 female mice 7–9 weeks old (Charles River Laboratories Italia SRL, Calco, Italy) were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected with 5 × 104 of either MC38 or LLC parental tumor cells or tumors transfected with CIITA expression vector, resuspended in 100 µL of RPMI (Lonza BioWhittaker™, Catalog number: BE12-702F) without FCS. The expression of CIITA-driven MHC-II was confirmed the day of the injection by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry as described above. The growth of tumors along with the overall health condition of the mice was checked at least twice per week. The tumors were measured weekly using a caliper and registered in mm2.

The mice that did not show any tumor growth after their injection with CIITA-transfected tumor cells were challenged with a s.c. injection of 2 × 105 parental tumor cells (four times the number of the first CIITA-expressing tumor cells injection).

Each experiment was repeated at least twice using 5–8 mice per group. All animal work has been conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines and was approved by the University of Insubria Internal Ethical Committee CESA (project 07–2013) and by the Italian Ministry of Health.

Adoptive cell transfer

Spleens from challenged mice that did not show parental tumor growth after 4 weeks from injection were harvested and processed. A single cell suspension was obtained and used to purify CD4+, CD8+ T cells by CD4+/8a+ Mouse T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Order number 130-095-248/130-090-859, respectively) and CD19+ B cells using Easy Sep Mouse B Cell Enrichment Kit (STEMCELL Technologies™, Catalog number: 19754). The purity of the purified cells was confirmed by flow cytometry using 145–2C11 anti-CD3e (Becton Dickinson, Catalog number: 553066) and RM4–5 anti-CD4+ (Becton Dickinson, Catalog number: 550954), 53–6.7 anti-CD8a (Biolegend®, Catalog number: 100711) and 6D5 anti-CD19 (Biolegend®, Catalog number: 115511) antibodies.

Normal splenocytes were obtained from naive C57BL/6 female mice of the same age. Naive female mice, 7–9 weeks old, were s.c. co-injected with 2 × 105 parental MC38 or LLC tumor cells, in a 100 µL volume of RPMI without FCS, along with either immune total splenocytes, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, or total naive splenocytes as a control, in a tumor cells:immune cells ratios of 1:50, 1:15, 1:10, 1:25 and 1:50, respectively. The experiment was repeated at least twice using 5–8 mice per group. The mice under experimentation were followed for 4–5 weeks and the data were recorded as described before.

Dendritic cells depletion in CD11c.DTR transgenic C57BL/6 mice

CD11c.DTR C57BL/6 mice transgenic male (kindly provided by Dr. N. Garbi, University of Bonn, Germany) were bred with wild type (WT) C57BL/6 females purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Genotyping was performed on the offsprings in order to select the transgenic progeny. The DNA was extracted from tail-cuts and PCR was done for the β2microglobulin as a reference gene and for the Ovalbumin (OVA) as a reporter gene by using the following primers

OVA1 5′-AACCTGTGCAGATGATGTACCA-3′

OVA2 5′-GCGATGTGCTTGATACAGAAGA-3′

βm 1 5′-CACCGGAGAATGGGAAGCCGAA-3′

βm 2 5′-TCCACACAGATGGAGCGTCCAG-3′

Primers were obtained from Tib Molbiol Srl, Genova, Italy. Following the protocol established by Hochweller et al.,18 the selected transgenic female mice (7–9 weeks old) were daily injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with DT (SIGMA-ALDRICH, Catalog number: D0564) for 11 d starting 48 h prior to tumor injection. Each mouse was injected with 8 ng/gbw of DT in a 100 µL volume of RPMI without FCS. MHC-II+ DC depletion was confirmed by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry analysis of CD11c+ cells, using the HL3 anti-CD11c antibody (Becton Dickinson, Catalog number: 561044), and the M5/114.15.2 anti-IA antibody on splenocytes isolated from transgenic mice sacrificed 72 h after their first DT injection and compared with splenocytes of wild-type mice.

Equal numbers (5 × 104) of either MC38-CIITA or LLC-CIITA tumor cells were s.c. injected in DT treated and untreated CD11c.DTR C57BL/6 female mice. Each group contains at least five mice. The experiment was repeated three times. The mice under experimentation were followed for 4 weeks and the data were recorded as described before.

Macrophages depletion with liposomal clodronate

250 µL of 5 mg/mL Liposomal Clodronate (LClo) (http://www.clodronateliposomes.org), a potent anti-macrophage agent that upon phagocytosis induces an irreversible damage of the cell which then dies by apoptosis,29 were injected i.p. every 3 d for 2 weeks starting 4 d before tumors injections. Macrophages depletion was confirmed by flow cytometric analysis of peritoneal and spleen cells stained with the F4/80 anti-mouse macrophage antibody (BioLegend®, clone BM8 Catalog number:123107) and the M5/114.15.2 anti-IA antibody on the following day of the second LClo injection.

Equal numbers (5 × 104) of MC38-CIITA tumor cells were s.c. injected in LClo-treated and untreated C57BL/6 female mice. Each group contains at least five mice. The experiment was performed two times. The mice under experimentation were followed for 4 weeks and the data were recorded as described before.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 and Student's t-test was run to determine the significance. The results were considered significant if p values were < 0.01.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants: European Community FP7 Grant no. 602893 “Cancer Vaccine Development for Hepatocellular Carcinoma-HepaVAC” http://www.hepavac.eu (to RSA, GT and GF); Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro http://www.airc.it “New strategies of tumor vaccination and immunotherapy based on optimized triggering of anti-tumor CD4+ T cells” (AIRC IG Grant no. 8862) (to RSA); Italian Ministry of University and Research project PRIN “New strategies of immunointervention against tumors” (2008-WXF7KK) (to RSA); University of Insubria “FAR 2014 and 2015” (to RSA, GF and GT). GF was supported by University of Insubria and Regione Lombardia Consortium Project DOTE-UNIRE: TumVac, New Strategies of Anti-Tumor Vaccination.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011; 144:646-74; PMID:21376230; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn JP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu Rev Immunol 2004; 22:329-60; PMID:15032581; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med 2004; 10:909-15; PMID:15340416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vesely M, Kershaw M, Schreiber R, Smyth M. Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu Rev Immunol 2011; 29:235-71; PMID:21219185; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Germain RN, Margulies DH. The biochemistry and cellular biology of antigen processing and presentation. Annu Rev Immunol 1993; 11:403-50; PMID:8476568.; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.02155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonifaz LC, Bonnyay DP, Charalambous A, Darguste DI, Fujii S, Soares H, Brimnes MK, Moltedo B, Moran TM, Steinman RM. In vivo targeting of antigens to maturing dendritic cells via the DEC-205 receptor improves T cell vaccination. J Exp Med 2004; 199:815-24; PMID:15024047; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20032220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: versatile controllers of the immune system. Nature Med 2007; 13:1155-9; PMID:17917664; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.038/nm643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardoll DM, Topalian SL. The role of CD4+ T cell responses in anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 1998; 10:588-94; PMID:9794842; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0952-7915(98)80228-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll DM, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4+ T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med 1998; 188:2357-68; PMID:9858522; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boon T, Cerottini JC, Van den Eynde B, Van der Bruggen P, Van Pel A. Tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol 1994; 12:337-65; PMID:8011285; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.02005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meazza R, Comes A, Orengo AM, Ferrini S, and Accolla RS. Tumor rejection by gene transfer of the MHC class II transactivator in murine mammary adenocarcinoma cells. Eur J Immunol 2003; 33:1183-92; PMID:12731043; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.58/078-0432.CCR-06-165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortara L, Castellani P, Meazza R, Tosi G, De Lerma Barbaro A, Procopio FA, Comes A, Zardi L, Ferrini S, Accolla RS. CIITA-induced MHC class II expression in mammary adenocarcinoma leads to a Th1 polarization of the tumor microenvironment, tumor rejection, and specific antitumor memory. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12:3435-43; PMID:16740768; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/078-0432.CCR-06-165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mortara L, Frangione V, Castellani P, De Lerma Barbaro A, Accolla RS. Irradiated CIITA-positive mammary adenocarcinoma cells act as a potent anti-tumor-preventive vaccine by inducing tumor-specific CD4+ T cell priming and CD8+ T cell effector functions. Int Immunol 2009; 21:655-65; PMID:19395374; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/intimm/dxp034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frangione V, Mortara L, Castellani P, De Lerma Barbaro A, Accolla RS. CIITA-driven MHC-II positive tumor cells: preventive vaccines and superior generators of anti-tumor CD4+ T lymphocytes for immunotherapy. Int J Cancer 2010; 127:1614-24; PMID:20091859; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.002/ijc.25183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accolla RS, Tosi G. Adequate antigen availability: a key issue for novel approaches to tumor vaccination and tumor immunotherapy. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2013; 8:28-36; PMID:23224729; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11481-012-9423-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Accolla RS, Lombardo L, Abdallah R, Raval G, Forlani G, Tosi G. Boosting the MHC class II-restricted tumor antigen presentation to CD4+ T helper cells: a critical issue for triggering protective immunity and re-orienting the tumor microenvironment toward an anti-tumor state. Frontiers Oncol 2014; 4:32; PMID:23986750; http://dx.doi.org/6296871 10.3389/fonc.2014.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathis DJ, Benoist C, Williams VE, Kanter M, McDevitt HO. Several mechanisms can account for defective Ea gene expression in different mouse haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1983; 80:273-7; PMID:6296871; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.80.1.273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochweller K, Striegler J, Hammerling GJ, Garbi N. A novel CD11c.DTR transgenic mouse for depletion of dendritic cells reveals their requirement for homeostatic proliferation of natural killer cells. Eur J Immunol 2008; 38:2776-83; PMID:18825750; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.200838659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods 1994; 174:83-93; PMID:8083541; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Probst HC, Tschannen K, Odermatt B, Schwendener R, Zinkernagel RM, Van Den Broek M. Histological analysis of CD11c-DTR/GFP mice after in vivo depletion of dendritic cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2005; 141:398-404; PMID:16045728; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.365-2249.005.02868.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernhard CA, Ried C, Kochanek S, Brocker T. CD169+ macrophages are sufficient for priming of CTLs with specificities left out by crosspriming dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112:5461-6; PMID:25922518; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1423356112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seiler P, Aichele P, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Schwendener RA. Crucial role of marginal zone macrophages and marginal zone metallophils in the clearance of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. Eur J Immunol 1997; 27:2626-33; PMID:9368619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.1830271023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sartoris S, Valle MT, De Lerma Barbaro A, Tosi G, Cestari T, D'Agostino A, Megiovanni AM, Manca F, Accolla RS. HLA class II expression in uninducible hepatocarcinoma cells after trasfection of the AIR-1 gene product CIITA. Acquisition of antigen processing and presentation capacity. J Immunol 1998; 161:814-20; PMID:9670958 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer immunity cycle. Immunity 2013; 39:1-10; PMID:23890059; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.16/j.immuni.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol 2005; 23:515-48; PMID:15771580; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aloisi F, Pujol-Borrell R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nature Rev Immunol 2006; 6:205-17; PMID:16498451; http://dx.doi.org/25443495 10.1038/nri786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dieu-Nosjean MC, Goc J, Giraldo NA, Sautes-Fridman C, Fridman WH. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends Immunol 2014; 35:571-80; PMID:25443495; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.it.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steimle V, Otten LA, Zufferey M, Mach B. Complementation cloning of an MHC class II transactivator mutated in hereditary MHC class II deficiency (or Bare Lymphocyte Syndrome). Cell 1993; 75:135-46; PMID:8402893; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80090-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Rooijen N, Sanders A, van den Berg TK. Apoptosis of macrophages induced by liposome-mediated intracellular delivery of and propamidine. J Immunol Methods 1996; 193:93-9; PMID:8690935; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00056-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]