ABSTRACT

Cutaneous angiosarcoma (CAS) is a malignant sarcoma with poor prognosis. Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death-1 ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression reflects antitumor immunity, and is associated with patient prognosis in various cancers. The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between PD-1/PD-L1 expression and CAS prognosis. CAS cases (n = 106) were immunohistochemically studied for PD-L1 and PD-1 expression, and the correlation with patient prognosis was analyzed. PD-L1 expression was assessed by flow cytometry on three CAS cell lines with or without IFNγ stimulation. A total of 30.2% of patients' samples were positive for PD-L1, and 17.9% showed a high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells. Univariate analysis showed a significant relationship between a high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells with tumor site PD-L1 expression and favorable survival in stage 1 patients (p = 0.014, log-rank test). Multivariable Cox-proportional hazard regression analysis also showed that patients with a high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells with tumor site PD-L1 expression were more likely to have favorable survival, after adjustment with possible confounders (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.38, p = 0.021, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.16–0.86). Immunofluorescence staining of CAS samples revealed that PD-L1-positive cells were adjacent to PD-1-positive cells and/or tumor stroma with high IFNγ expression. In vitro stimulation with IFNγ increased PD-L1 expression in two out of three established CAS cell lines. Our results suggest that PD-1/PD-L1 expression is related to CAS progression, and the treatment with anti-PD-1 antibodies could be a new therapeutic option for CAS.

KEYWORDS: Cutaneous angiosarcoma, IFNγ, PD-1, PD-L1, T cells

Introduction

Angiosaroma is a malignant sarcoma that is thought to originate from endothelial cells of the blood or lymphatic vessels. Angiosarcoma is relatively rare, comprising 1% to 2% of sarcoma cases, and mostly occurs in skin as cutaneous angiosarcoma (CAS).1 CAS commonly affects the face and scalp of the elderly, and can develop with radiodermatitis and chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome).2-4 Treatment includes surgical excisions, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Recent reports have suggested the significant efficacy of continued with taxanes.5-7 Patients' prognosis, however, remains poor with a 5-y survival of approximately 10% to 20% due to the eventual formation of distant metastases.8-10

The development of more effective treatments is therefore required, and immunotherapy could be a therapeutic option. Fujii et al. reported that antitumor immunity with CD8+ T cells in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is important to prevent the progression of CAS.11 Certain types of human cancers express programmed cell death-1 ligand-1 (PD-L1) on the cell surface, which enables cancer cells to escape immune reactions by binding the inhibitory receptor programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) on T cells.12 Clinically, tumor PD-L1 expression affects patients' prognosis, and anti-PD-1-antibody administration has shown significant efficacy in treating several malignancies.13-15 The relationship between PD-1/PD-L1 expression and CAS progression has not, however, been examined to date.

In this study, we investigated PD-L1 and PD-1 expression in CAS histological specimens using immunohistochemistry, and linked the data to patients' prognosis. We found that patients with both high levels of PD-1-positive cells and high PD-L1 expression within the tumor had a significantly favorable prognosis. Moreover, flow cytometric analysis of CAS cell lines revealed the expression of PD-L1 on the surface of CAS tumor cells, which was further increased by interferon (IFN)-γ stimulation in vitro. Our data indicate that the blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 expression may be a new therapeutic target for CAS.

Results

Patients' characteristics and intra tumor of PD-L1 and PD-1 expression

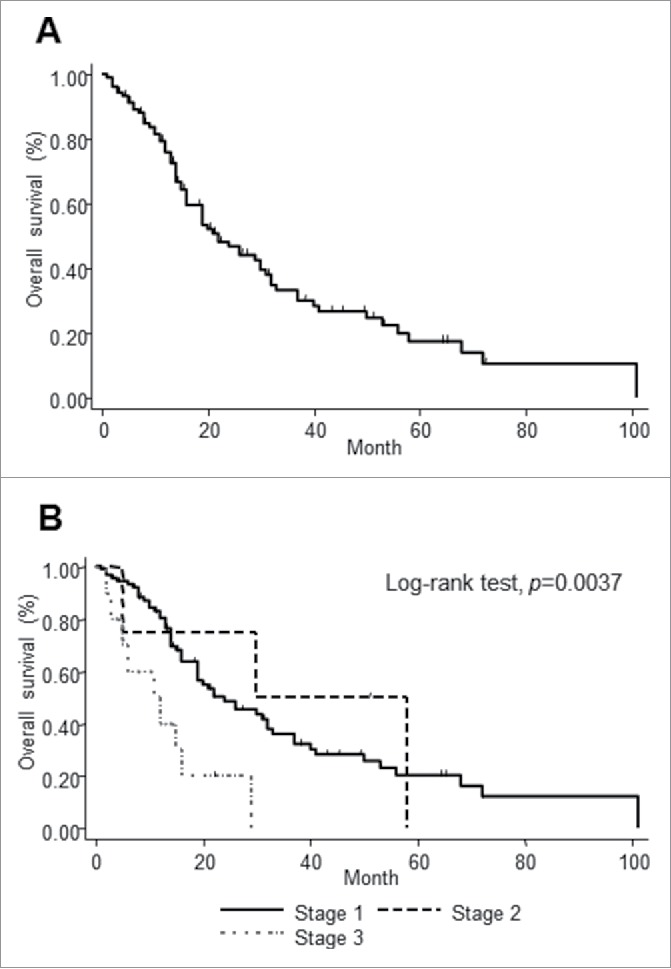

The patients' clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Male patients were dominant (70.8%), and the median age was 74.5 y. A total of 86.8% of patients were included in stage I, whereas only 13.2% were included in stages II and III. The scalp and face were the primary tumor sites in most participants (93.4%). A total of 30.2% of patients' samples were positive for PD-L1, and 17.9% showed PD-1-positive cells. A total of 8.5% of patients' samples were positive for both PD-L1 and PD-1. The 5-y survival rate for all patients with CAS was 17.5% (Fig. 1A). Patients in stage I showed a better prognosis than those in stages II and III (p = 0.0037, log-rank test) (Fig. 1B). The PD-L1/PD-1 expression was not correlated with stage (PD-L1: p = 0.080, PD-1: p = 0.068) (Figs. S1A and B). Although 11 out of 106 samples were taken after systemic treatments, we did not find significant difference in the PD-L1/PD-1 expression between the non-treated group and the treated group (PD-L1: p = 0.87, PD-1: p = 0.39) (Figs. S2A and B).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and expressional status of PD-L1 and PD-1 in CAS.

| All patients n = 106 | PD-L1 (+) n = 32 (30%) | PD-1 high n = 19 (18%) | PD-L1 (+), PD-1 high n = 9 (8.5%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 31 (29%) | 10 (31%) | 4 (21%) | 2 (22%) |

| Male | 75 (71%) | 22 (69%) | 15 (79%) | 7 (78%) |

| Age | 74.5 | 74.25 | 69.3 | 68.6 |

| Stage | ||||

| I | 92 (87%) | 32 (100%) | 18 (95%) | 9 (100%) |

| II+III | 14 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Anatomical distribution | ||||

| Face/scalp | 99 (93%) | 30 (28%) | 17 (89%) | 8 (89%) |

| Breast | 2 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Leg | 3 (2.8%) | 1 (3.1%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (3.1%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (11%) |

| Therapy | ||||

| Taxane | 72 (68%) | 23 (72%) | 17 (89%) | 7 (78%) |

| Radiation | 68 (64%) | 17 (53%) | 15 (79%) | 7 (78%) |

| Surgery | 38 (36%) | 14 (44%) | 5 (26%) | 3 (33%) |

| Others | 8 (7.5%) | 5 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Figure 1.

The survival curve of all the patients with CAS. The survival curve of all patients with CAS (A). Patients were divided into three groups depending on clinical stages. Survival differences were analyzed by log-rank test (B).

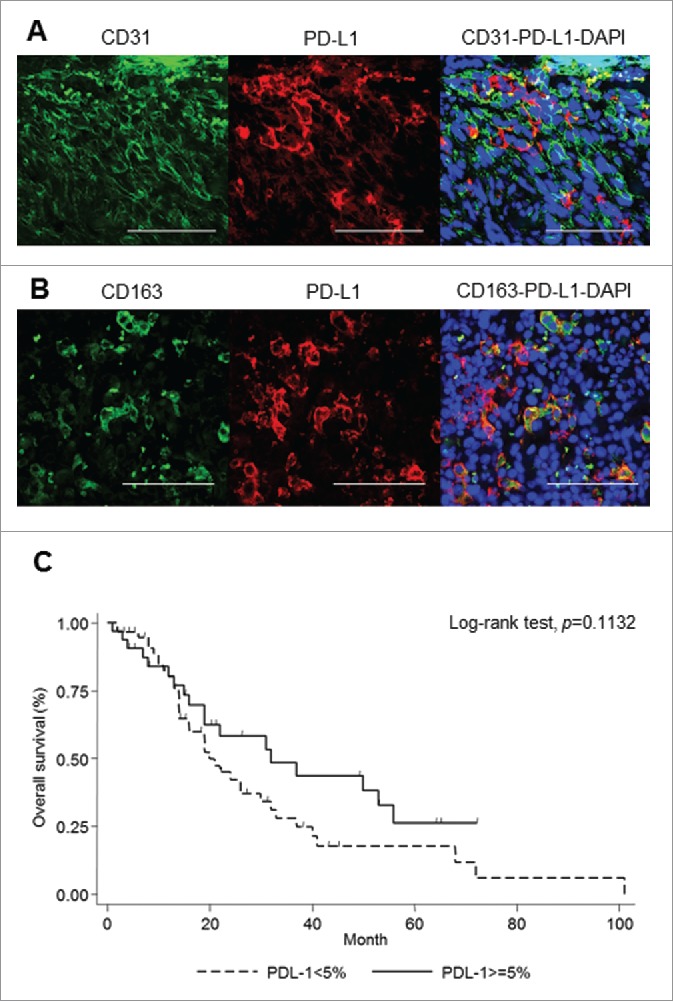

Tumor site PD-L1 expression was associated with a slight but not significant increase in survival

In addition to cancer cells, immune cells such as macrophages also express PD-L1 at the tumor site.16 To identify which cells express PD-L1 in CAS, we analyzed PD-L1-positive cells with immunofluorescence. CD31 was used as a marker for cancer cells and CD163 as a marker for macrophages as previously described. Therefore, double immunofluorescence staining was performed for PD-L1/CD31 and PD-L1/CD163 in three PD-L1-positive samples. The mean ratio of double-positive cells in PD-L1-positive cells was calculated. A total of 51.5% of PD-L1-positive cells also expressed CD31 (Fig. 2A), and 36.7% of PD-L1-positive cells also expressed CD163 (Fig. 2B). This result suggests that both cancer cells and macrophages express PD-L1 in CAS.

Figure 2.

PD-L1 expression in CAS. Evaluation of PD-L1-positive cells at the tumor site. Representative double immunofluorescence staining of CD31 (green) and PD-L1 (red) (A), and CD163 (green) and PD-L1 (red). Scale bar, 50 μm (B). Tumor site expression of PD-L1 was not significantly correlated with overall survival in stage 1 patients with CAS (C).

The survival curve showed a tendency of favorable prognosis for patients expressing PD-L1, but the log-rank test showed no significance (p = 0.11) (Fig. 2C). The log-rank tests showed no significance using 1% as a cutoff (p = 0.27) (Fig. S3A) and 10% as a cutoff (p = 0.11) (Fig. S3B) of PD-L1 expression, which were same as that of 5%. Multivariable Cox-proportional hazard regression analysis, after adjustment with possible confounders, did not show a significant difference in prognosis for patients with high PD-L1 expression either (HR = 0.62, p = 0.109, 95% CI 0.35–1.11) (Table S1).

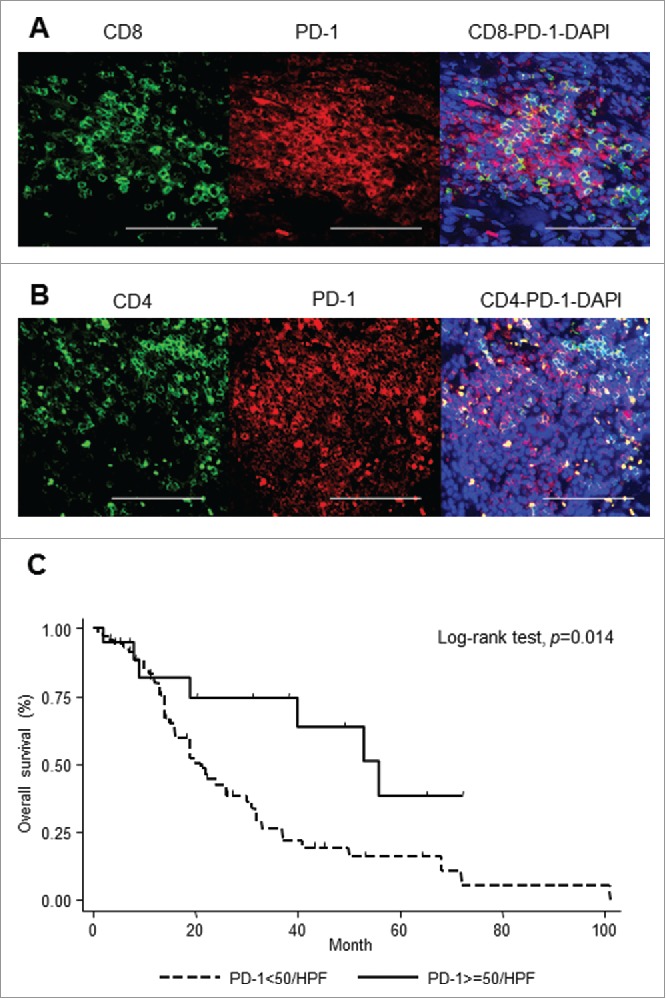

High infiltration of PD-1-positive cells is related to a favorable prognosis

In order to examine the phenotype of PD-1-positive cells in CAS, double immunofluorescence staining was performed for PD-1/CD8+ and PD-1/CD4+ using samples with PD-1-high infiltration. A total of 48.6% of PD-1-positive cells expressed CD8+ (Fig. 3A), and 43.2% of PD-1-positive cells expressed CD4+ (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that both CD4-positive and CD8-positive tumor infiltrating cells can express PD-1.

Figure 3.

PD-1 expression in CAS. Evaluation of phenotype of PD-1-positive cells. Representative double immunofluorescence staining of CD8+ (green) and PD-1 (red) (A), and CD4+ (green) and PD-1 (red). Scale bar, 50 μm (B). Correlation of PD-1 expression with overall survival in stage 1 patients with CAS (C).

Univariate analysis showed a significant relationship between a high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells and favorable prognosis (p = 0.014) (Fig. 3C). Multivariable Cox-proportional hazard regression analysis also showed that patients with a high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells were more likely to have a favorable prognosis, after adjustment with possible confounders (HR = 0.38, p = 0.021, 95% CI 0.16–0.86) (Table S2).

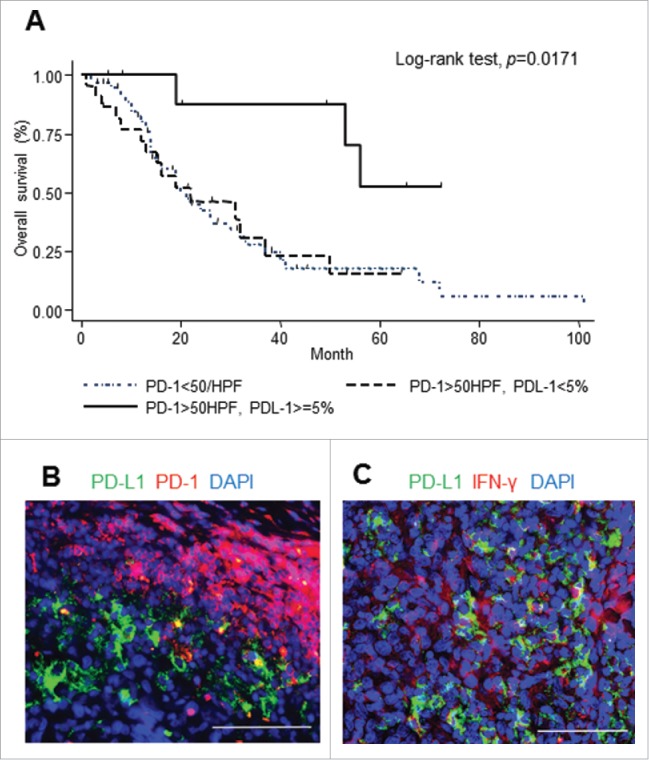

Patients with high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells with tumor site PD-L1 expression showed the most favorable prognosis

Among the group with high PD-1 infiltration, patients with PD-L1 expression at the tumor site showed better survival compared to those without (Fig. 4A). Multivariable Cox-proportional hazard regression analysis supported this observation (HR = 0.19, p = 0.008, 95% CI 0.54–0.65) (Table S3). Next, we found the relative proximity of PD-1 and PD-L1 as evidence of a physical interaction between PD-1-positive and PD-L1-positive cells using immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 4B). PD-1/PD-L1 signaling may therefore play a role in the pathogenesis of CAS.

Figure 4.

PD-1 expression and PD-L1 expression in CAS. PD-1-positive cells with tumor site PD-L1 expression was significantly related to improved outcomes (A). Representative double immunofluorescence staining of PD-L1 (green) and PD-1 (red) (B), and PD-L1 (green) and IFNγ (red) (C). Scale bar, 50 μm.

IFNγ was expressed around PD-L1-positive cells at the tumor stroma

It is known that PD-L1 expression on cancer cells can be induced by IFNγ stimulation.17,18 Abiko et al. suggested that direct contact with T cells is essential to induce PD-L1 expression in ovarian cancers via IFNγ.18 We performed double immunofluorescence staining for PD-L1/IFNγ for the sample with high PD-L1 expression. We observed that PD-L1-positive cells were indeed surrounded by IFNγ (Fig. 4C). PD-L1 expression on cancer cells in CAS may therefore be caused by IFNγ.

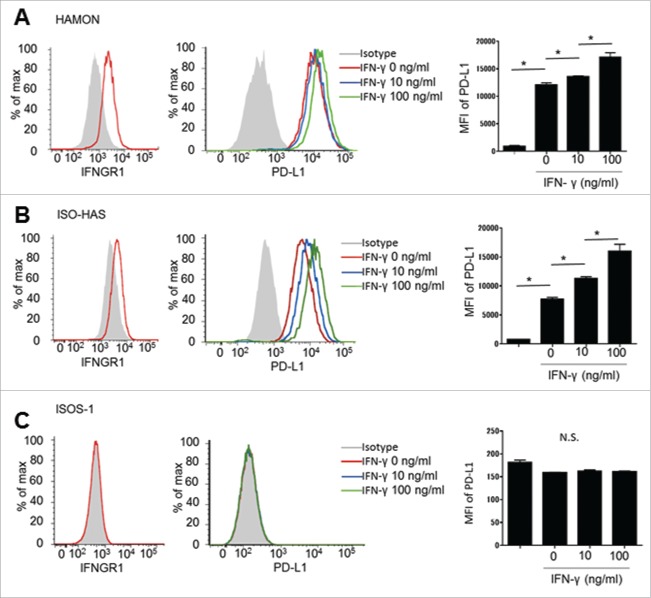

PD-L1 expression in CAS cell lines was observed in the steady state, and increased by IFNγ stimulation

An in vitro assay was performed to investigate whether CAS cancer cells express PD-L1 in direct response to IFNγ stimulation. Two of the cell lines, HAMON and ISO-HAS, expressed IFNGR1, the receptor for IFNγ with flow cytometric analysis (Figs. 5A and B). However, ISOS-1 lacked IFNGR1 (Fig. 5C). The cell lines were cultured with or without IFNγ, and PD-L1 expression was analyzed using flow cytometry. PD-L1 was constitutively expressed on HAMON and ISO-HAS cells, and was augmented by IFNγ stimulation in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 5A and B). However, ISOS-1, which lacks IFNGR1, did not express PD-L1 even after IFNγ stimulation (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that CAS cells may constitutively express PD-L1 and increase their expression in response to IFNγ.

Figure 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of IFNGR1 and PD-L1 with/without IFNγ exposure. HAMON and ISO-HAS express IFNGR1 and PD-L1 without any stimulation. PD-L1 expression was increased with IFNγ stimulation. Asterisk indicates significance, p < 0.005. (A and B). ISOS-1 does not express IFNGR1 or PD-L1 (C).

Discussion

In this study, we revealed that a high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells, especially when accompanied with tumor site PD-L1 expression, is a favorable prognostic factor in CAS. PD-L1 was expressed by both cancer cells and macrophages, and PD-L1-positive cells were adjacent to PD-1-positive cells and IFNγ expression. In vitro experiments showed that some CAS cell lines constitutively express PD-L1 and can increase the expression in response to IFNγ stimulation.

Previous reports showed that the PD-L1 and PD-1 expressions were associated with either good or poor prognosis in various cancers. The PD-L1 expression was related to a poor prognosis in malignant melanoma, esophageal cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, and renal cell carcinoma by immune resistance.12,19-22 On the other hand, PD-L1 expression was associated with a good prognosis in Merkel cell carcinoma possibly by reflecting antitumor immunity.23 As for CAS, our data showed that the PD-L1 expression was correlated with better survival only when accompanied with a high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells.

PD-1 expression is known to be associated with a poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma.24,25 Hsu et al. suggested that PD-1-positive CD8+ T cells are associated with suppression of cytotoxic lymphocytes in tumor tissue.26 On the other hand, PD-1-positive TILs were associated with a favorable prognosis in HNSCC.27 Interestingly, in HNSCC, a high infiltration of PD-1-positive CD4-positive T cells, but not CD8-positive T cells, reflected a favorable prognosis.27 As for CAS, our study showed that PD-1 expression on T cells were correlated with better survival, and that both CD4-positive and CD8-positive cells expressed PD-1. Since PD-1 expression is regarded as both an activation and an exhaustion marker of T cells,28 these observations indicate that the phenotypes of PD-1-positive cells vary in each cancer type, and may reflect either active immune responses or a lack thereof.

It is known that tumor cells express PD-L1 by oncogene-driven mechanisms, and adaptive-resistant mechanisms in response to IFNγ secreted from T cells.29,30 In addition, since blood endothelial cells express PD-L1,31 CAS cells may express PD-L1 intrinsically. In vitro experiments using CAS cell lines exhibited PD-L1 expression in cancer cells irrespective of IFNγ stimulation. The fact that some CAS cells lines constitutively expressed PD-L1 regardless of IFNγ stimulation indicates that the cells arose from already expressed PD-L1 or as a result of oncogenic mutations. Moreover, IFNγ may further enhance tumor PD-L1 expression in patients.

In our study, patients with PD-1-positive cells, especially when accompanied with tumor PD-L1 expression, showed a significantly improved prognosis compared to other patients. Considering these findings, we deduce that a high infiltration of PD-1-positive cells might reflect antitumor immune responses in CAS, which could also result in PD-L1 expression at the tumor site via IFNγ by activated T cells.

In conclusion, our study suggests that the infiltration of PD-1-positive cells is related to CAS patients' prognoses; therefore, the treatment with anti-PD-1 antibodies can be a new therapeutic option for CAS.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Paraffin-embedded cancer tissue samples were obtained from patients (n = 106) who were diagnosed with CAS between September in 1996 and February in 2016 at nine hospitals in Japan: Kyoto University Hospital; Niigata Cancer Centre; Kagoshima University Hospital; University of the Ryukyus Hospital; Hokkaido University Hospital; Tohoku University Hospital; Keio University Hospital; Tsukuba University Hospital; and Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious Diseases Centre Komagome Hospital. Clinical information included patient age, sex, tumor site, overall survival, and treatment. We classified patient groups into three stages as reported previously, stage I for patients with local tumors, stage II for patients with lymph node involvement, and stage III for patients with distant metastases.11,32 Computed tomography (CT) was used to detect metastasis of lymph nodes and distant organs. 11 out of 106 samples were taken after systemic treatments including taxanes and pasopanib.

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

PD-L1 and PD-1 assessment by immunohistochemistry

Deparaffinization, antigen retrieval, and immunohistochemistry were carried out using Ventana Discovery (Ventana Medical Systems). PD-L1 expression was examined using anti-human PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (Clone SP142; Spring Bioscience, CA). Over 5% of membranous expression at the tumor site was defined as positive (Fig. S4).33 PD-1 expression analysis was performed using anti-human PD-1 monoclonal antibody (Clone NAT105; Abcam). The number of PD-1-positive cells was counted individually in three visual fields with high-power fields (HPF × 400). High infiltration was determined when the mean was more than 50 positive cells, and low infiltration was determined when less than 50 positive cells were observed (Fig. S5).

Immunofluorescence staining

Tissue samples were deparaffinized, and underwent heat-mediated antigen retrieval. Double immunofluorescent staining was performed for PD-L1 and CD31, PD-L1 and CD163, PD-1 and CD4+, PD-1 and CD8+, and PD-1 and PD-L1. The antibodies used were PD-L1 (Clone SP142; Spring Bioscience), CD31 (Clone JC70A; DAKO), CD163 (Clone 10D6; Novocastra), PD-1 (Clone NAT105; Abcam), CD4+ (Clone SP35; Cell Marque), CD8+ (Clone EP1105Y; Abcam), and IFNγ (Clone ab9657; Abcam). Fluorescent images were analyzed with a fluorescence microscope (Bio-Revo, Keyence). The numbers of PD-L1-positive cells, CD31-positive cells, and CD163-positive cells were counted respectively in seven respective visual fields from three samples with high-power fields (HPF × 400). The mean ratio of PD-1-positive cells expressing CD4+ and CD8+ was calculated in the same manner.

Statistical analysis

Survival was measured starting from the date of CAS diagnosis until patient death or until the end of the study (June 2015). The survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was performed for the univariate analysis. Cox-proportional hazard regression models were employed to examine the relationship between the expression of PD-L1 or PD-1 and mortality in stage I patients. Cox-proportional hazard regression models were adjusted for age, gender, and taxane therapy. p values were two-tailed, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Cell line

The human CAS cell lines, HAMON, were obtained from Hokkaido University in February 2016, and ISO-HAS and ISOS-1 were obtained from Kitasato University in February 2016. They were cultured as previously described,34-36 and were used in fewer than 6 mo of continuous passage. The cell lines were incubated with or without 10 ng/mL or 100 ng/mL recombinant human IFNγ (R&D) for 24 h before analysis.

Flow cytometric analysis

The CAS cell lines were stained with the following monoclonal antibodies: allophycocyanin (APC) conjugated anti-PD-L1 (clone M1H1; eBioscience); phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated anti interferon gamma receptor 1 (IFNGR1) (clone GIR 208; eBioscience). Samples were acquired using LSR Fortessa (BD Bioscience) and analyzed using Flow Jo software (Tree Star).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Hidaka Yokota, Noriko Kawabata, and Hideki Nakajima for providing clinical information.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (15H05790), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (15H1155), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grant-in-Aid for challenging Exploratory Research (15K15417), Japan Science and Technology Agency, Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology (PRESTO) (16021031300), and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (16ek0410011h0003, 16he0902003h0002).

References

- 1.Coindre JM, Terrier P, Guillou L, Le Doussal V, Collin F, Ranchere D, Sastre X, Vilain MO, Bonichon F, N'Guyen Bui B. Predictive value of grade for metastasis development in the main histologic types of adult soft tissue sarcomas: a study of 1240 patients from the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group. Cancer 2001; 91:1914-26; PMID:11346874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/1097-0142(20010515)91:10%3c1914::AID-CNCR1214%3e3.0.CO;2-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgkinson DJ, Soule EH, Woods JE. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer 1979; 44:1106-13; PMID:573173; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/1097-0142(197909)44:3%3c1106::AID-CNCR2820440345%3e3.0.CO;2-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brady A, Al-Kalbani M, Al Rawahi T, Nagar H, McCluggage WG. Postirradiation primary vaginal angiosarcoma with widespread intra-abdominal metastasis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2011; 30:514-7; PMID:21804395; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PGP.0b013e318214bd05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behranwala KA, A'Hern R, Omar AM, Thomas JM. Prognosis of lymph node metastasis in soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2004; 11:714-9; PMID:15231526; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1245/ASO.2004.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, Kadono T, Miyagawa T, Nakamura Y, Fujimoto M. Chemoradiotherapy with taxane is superior to conventional surgery and radiotherapy in the management of cutaneous angiosarcoma: a multicentre, retrospective study. Br J Dermatol 2014; 171:1493-500; PMID:24814962; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/bjd.13110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito T, Uchi H, Nakahara T, Tsuji G, Oda Y, Hagihara A, Furue M. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and face: a single-center analysis of treatment outcomes in 43 patients in Japan. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2016; 142:1387-94; PMID:27015673; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00432-016-2151-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, Cupissol D, Ray-Coquard I, Piperno-Neumann S, Kerbrat P, Fournier C, Taieb S, Jimenez M et al.. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX Study. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:5269-74; PMID:18809609; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez MC, Padhya TA, Messina JL, Jackson RS, Gonzalez RJ, Bui MM, Letson GD, Cruse CW, Lavey RS, Cheong D et al.. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20:3391-7; PMID:23835652; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1245/s10434-013-3083-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donghi D, Kerl K, Dummer R, Schoenewolf N, Cozzio A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: own experience over 13 years. Clinical features, disease course and immunohistochemical profile. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24:1230-4; PMID:20236193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fury MG, Antonescu CR, Van Zee KJ, Brennan MF, Maki RG. A 14-year retrospective review of angiosarcoma: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and treatment outcomes with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer J 2005; 11:241-7; PMID:16053668; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00130404-200505000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii H, Arakawa A, Utsumi D, Sumiyoshi S, Yamamoto Y, Kitoh A, Ono M, Matsumura Y, Kato M, Konishi K et al.. CD8(+) tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes at primary sites as a possible prognostic factor of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Int J Cancer 2014; 134:2393-402; PMID:24243586; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.28581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hino R, Kabashima K, Kato Y, Yagi H, Nakamura M, Honjo T, Okazaki T, Tokura Y. Tumor cell expression of programmed cell death-1 ligand 1 is a prognostic factor for malignant melanoma. Cancer 2010; 116:1757-66; PMID:20143437; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.24899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB et al.. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2443-54; PMID:22658127; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, Stinchcombe TE, Dy GK, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Lena H, Minenza E, Mennecier B et al.. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:257-65; PMID:25704439; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, Schuster SJ, Millenson MM, Cattry D, Freeman GJ et al.. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:311-9; PMID:25482239; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuang DM, Zhao Q, Peng C, Xu J, Zhang JP, Wu C, Zheng L. Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma foster immune privilege and disease progression through PD-L1. J Exp Med 2009; 206:1327-37; PMID:19451266; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20082173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blank C, Brown I, Peterson AC, Spiotto M, Iwai Y, Honjo T, Gajewski TF. PD-L1/B7H-1 inhibits the effector phase of tumor rejection by T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res 2004; 64:1140-5; PMID:14871849; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abiko K, Mandai M, Hamanishi J, Yoshioka Y, Matsumura N, Baba T, Yamaguchi K, Murakami R, Yamamoto A, Kharma B et al.. PD-L1 on tumor cells is induced in ascites and promotes peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer through CTL dysfunction. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19:1363-74; PMID:23340297; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohigashi Y, Sho M, Yamada Y, Tsurui Y, Hamada K, Ikeda N, Mizuno T, Yoriki R, Kashizuka H, Yane K et al.. Clinical significance of programmed death-1 ligand-1 and programmed death-1 ligand-2 expression in human esophageal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11:2947-53; PMID:15837746; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Iwasaki M, Okazaki T, Tanaka Y, Yamaguchi K, Higuchi T, Yagi H, Takakura K, Minato N et al.. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:3360-5; PMID:17360651; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0611533104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nomi T, Sho M, Akahori T, Hamada K, Kubo A, Kanehiro H, Nakamura S, Enomoto K, Yagita H, Azuma M et al.. Clinical significance and therapeutic potential of the programmed death-1 ligand/programmed death-1 pathway in human pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13:2151-7; PMID:17404099; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu F, Xu L, Wang Q, An G, Feng G, Liu F. Clinicopathological and prognostic value of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) in renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8:14595-603; PMID:26628942 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipson EJ, Vincent JG, Loyo M, Kagohara LT, Luber BS, Wang H, Xu H, Nayar SK, Wang TS, Sidransky D et al.. PD-L1 expression in the Merkel cell carcinoma microenvironment: association with inflammation, Merkel cell polyomavirus and overall survival. Cancer Immunol Res 2013; 1:54-63; PMID:24416729; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson RH, Dong H, Lohse CM, Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Kwon ED. PD-1 is expressed by tumor-infiltrating immune cells and is associated with poor outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13:1757-61; PMID:17363529; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muenst S, Hoeller S, Dirnhofer S, Tzankov A. Increased programmed death-1+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in classical Hodgkin lymphoma substantiate reduced overall survival. Hum Pathol 2009; 40:1715-22; PMID:19695683; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu MC, Hsiao JR, Chang KC, Wu YH, Su IJ, Jin YT, Chang Y. Increase of programmed death-1-expressing intratumoral CD8 T cells predicts a poor prognosis for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2010; 23:1393-403; PMID:20657553; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/modpathol.2010.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badoual C, Hans S, Merillon N, Van Ryswick C, Ravel P, Benhamouda N, Levionnois E, Nizard M, Si-Mohamed A, Besnier N et al.. PD-1-expressing tumor-infiltrating T cells are a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 2013; 73:128-38; PMID:23135914; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sauce D, Almeida JR, Larsen M, Haro L, Autran B, Freeman GJ, Appay V. PD-1 expression on human CD8 T cells depends on both state of differentiation and activation status. AIDS 2007; 21:2005-13; PMID:17885290; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282eee548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsa AT, Waldron JS, Panner A, Crane CA, Parney IF, Barry JJ, Cachola KE, Murray JC, Tihan T, Jensen MC et al.. Loss of tumor suppressor PTEN function increases B7-H1 expression and immunoresistance in glioma. Nat Med 2007; 13:84-8; PMID:17159987; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandai M, Hamanishi J, Abiko K, Matsumura N, Baba T, Konishi I. Dual Faces of IFNgamma in Cancer Progression: A Role of PD-L1 Induction in the Determination of Pro- and Antitumor Immunity. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22:2329-34; PMID:27016309; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eppihimer MJ, Gunn J, Freeman GJ, Greenfield EA, Chernova T, Erickson J, Leonard JP. Expression and regulation of the PD-L1 immunoinhibitory molecule on microvascular endothelial cells. Microcirculation 2002; 9:133-45; PMID:11932780; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/713774061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.M M Angiosarcoma of the scalp: strategy and evaluation at Kitasato University Hospital. Skin Cancer (Jpn) 2009; 24:377-84; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5227/skincancer.24.377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, Xu H, Sharma R, McMiller TL, Chen S, Klein AP, Pardoll DM, Topalian SL et al.. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4:127ra37; PMID:22461641; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoshina D, Abe R, Yoshioka N, Saito N, Hata H, Fujita Y, Aoyagi S, Shimizu H. Establishment of a novel experimental model of human angiosarcoma and a VEGF-targeting therapeutic experiment. J Dermatol Sci 2013; 70:116-22; PMID:23522954; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masuzawa M, Fujimura T, Hamada Y, Fujita Y, Hara H, Nishiyama S, Katsuoka K, Tamauchi H, Sakurai Y. Establishment of a human hemangiosarcoma cell line (ISO-HAS). Int J Cancer 1999; 81:305-8; PMID:10188735; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990412)81:2%3c305::AID-IJC22%3e3.0.CO;2-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masuzawa M, Fujimura T, Tsubokawa M, Nishiyama S, Katsuoka K, Terada E, Kunita S, Sakurai Y, Kato H. Establishment of a new murine-phenotypic angiosarcoma cell line (ISOS-1). J Dermatol Sci 1998; 16:91-8; PMID:9459120; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0923-1811(97)00032-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.