Mucoadhesives have received much attention as they have been integrated into a rapidly expanding range of applications, including imaging and diagnostic electronics such as biosensors, tissue engineering, and biomedical implants.[1–3] They have also been extensively used in dosage formulations for various administration routes, including nasal, ocular, vaginal, and oral drug-delivery.[4,5] In particular, mucoadhesives have served as a key element for orally administered drug-delivery systems as they help prolong gastrointestinal (GI) residence time and provide controlled rate of drug release in a targeted region.[6–9] By adhering to the mucus layer of the GI tract, mucoadhesives allow for rapid absorption and enhanced penetration of drugs[7] as well as improved drug bioavailability, which could help reduce the frequency of drug administration.[5,10]

However, extended adhesion to the GI mucosa is significantly limited by the constant passage of food and bodily fluids.[11–14] GI motility and unavoidable interaction with the surrounding biological milieu lead to fouling and easy dislodgement of ingested systems (Figure 1a).[15–18] Thus, there is a need for a superior mucoadhesive system designed to minimize the interaction with food and bodily fluids, thereby reducing the likelihood of fouling and dislodgement.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the proposed dual-sided Janus device. Left, non-Janus device with adhesive surface on both sides, showing fouling and dislodgement (indicated by the red arrow). Right, Janus device with the addition of an omniphobic side, which minimizes the interaction with foodstuffs and thus reduces the likelihood of fouling and dislodgment. Blue arrows represent the flow direction of foodstuffs and other bodily fluids.

Janus devices, named after the double-faced Roman god Janus, have two faces each with unique properties at the opposite sides.[19] These systems have gained much attention in a broad set of applications, including magnetics, plasmonics, optics, and biomedical, due to their capacity to have multiple functionalities and properties.[20] Here, we propose a novel application of a Janus macro-system: a dual-sided device with an omniphobic side and an opposite mucoadhesive side. This system would enable repulsion of the food and fluid stream by the luminal-facing omniphobic side and allow attachment to the GI mucosa by the mucoadhesive side (Figure 1b).

In our design, Carbopol (C), a commerical mucoadhesive polymer that shows strong adhesion when wetted, was used as the mucoadhesive side. The omniphobic side was fabricated using an adapted version of the slippery liquid-infused porous surface system.[21] We incorporated bioinspired soft lithography that is facile and low-cost to replicate the patterned micro/nanostructures of a natural lotus leaf onto the omniphobic side.[22,23] The morphology of the modified surfaces was visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Omniphobicity and mucoadhesion of the surfaces were characterized by static contact angle goniometry with various liquids and also by detachment tests. Protein adsorption studies were conducted to confirm protection and antifouling of the omniphobic side. Ex vivo dislodgement evaluation, using porcine intestinal tissues and simulated fluid with foodstuffs, demonstrated extended retention of the dual-sided Janus device compared to non-Janus devices. With prolonged retention in the GI tract, this engineered Janus device has significant potential to reduce the frequency of drug administration and therefore promote medication compliance.[24]

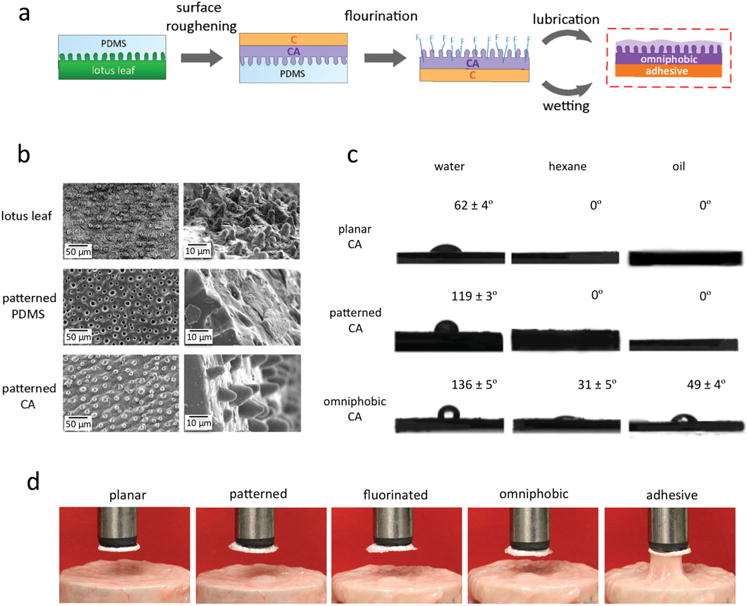

As schematically depicted in Figure 2a, a feasible strategy to manufacture the double-sided Janus device (Figure 1) was developed. The Janus device was constructed based on a dual-layered thin sheet, where the powder forms of Carbopol polymer and cellulose acetate (CA) polymer (in 1:1 ratio) were tablet-pressed, in the manner of one layer on top of the other. Then, the CA side was modified with the omniphobic coating through a three-step process: surface roughening, fluorination, and lubrication. First, for surface roughening, a biologically inspired soft lithography process was employed to produce an artificial polymer membrane that emulates the morphology of a natural lotus leaf. Specifically, a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) master mold was created, replicating the microscopic pillar structures from a fresh lotus leaf. This master mold served as an inexpensive template for top-down imprint lithography with acetone-wetted CA polymer membrane. Subsequently, the patterned CA membrane was chemically functionalized via vapor-phase fluorination with perfluorinated silane and then lubricated with a biocompatible, medical-grade perfluorocarbon liquid.[25] Thus, the lubricating fluid became naturally locked within the covalently-tethered fluorinated microposts through chemical affinity.[21] At completion of the fabrication process, the CA side displayed omniphobic properties and the Carbopol layer exhibited mucoadhesive properties upon wetting.

Figure 2.

Fabrication workflow of the Janus device and characterization of omniphobicity and mucoadhesiveness. a) The fabrication process scheme of the Janus device. First, the PDMS master mold with mimicked microposts from a natural lotus leaf is created by soft lithography. Second, using the master mold with a dual-layered polymer film, made from CA powder and C powder compressed together by a tablet-press, the microposts from the lotus leaf are replicated onto the CA side via reverse imprinting. Third, the patterned CA surface is fluorinated to facilitate subsequent lubrication through chemical affinity. Last, with lubrication of the patterned CA side and wetting of the C side, the Janus device with omniphobicity and mucoadhesiveness, respectively, is fabricated. b) SEM images for surface roughening step: top row, low and high magnification of the microposts on the natural lotus leaf surface; middle row, low, and high magnification of the microwells on the patterned PDMS master mold surface; and bottom row, low, and high magnification of the replicated microposts on the patterned CA surface. Scale bars are as shown. c) Contact angle measurements (mean ± s.d., n = 8): top, planar CA surface, middle, patterned CA surface with replicated microposts and bottom, omniphobic CA surface with fluorinated and lubricated microposts, using different liquids (water, hexane, and vegetable oil). d) Photograph examples from the detachment tests using porcine intestinal mucosa and various modified surfaces: (from left to right) planar CA, patterned CA with microposts, fluorinated patterned CA, omniphobic patterned CA, and adhesive Carbopol.

For evaluation of the surface roughening with the soft lithography process, SEM was used to examine the quality of the replicated microposts. In Figure 2 b, low and high magnification SEM images showed that the microposts were effectively translated without damage or any significant loss in length, with the micropost height of ≈10 μm maintained throughout the molding process. Moreover, nanoscale roughening was observed on the replicated surface, recapitulating the nanoprotrusions on a natural lotus leaf and further contributing to the hydrophobic properties (Figure S1, Supporting Information).[26] In Figure S2 (Supporting Information), the surface features were characterized by static contact angle analysis with water. In comparison to the related planar surfaces, the contact angles of the patterned surfaces increased by about 30° for PDMS and 57° for CA. The increases in the contact angles confirmed successful generation of hydrophobic surfaces via surface roughening with microscale and nanoscale structures. The incorporation of the lotus leaf-based soft lithography offered an attractive, low-cost method to fabricate hydrophobic surfaces in a rapid manner.

Omniphobicity of the CA surface was confirmed through static contact angle goniometry using a range of nonorganic and organic liquids (water, hexane, and vegetable oil in Figure 2c and additional solvents in Figure S3, Supporting Information). For the planar reference surfaces, θstatic, water = 62° ± 4°, θstatic, hexane = 0°, and θstatic, oil = 0°. For the patterned surfaces with replicated microposts, θstatic, water = 119° ± 3° and the contact angles for hexane and oil were 0°. The low water wettability confirmed the expected hydrophobicity from the surface roughening through micro/nanostructures, yet the patterned surface remained highly wettable to other liquids. For the omniphobic surfaces with morphological and chemical modifications, the water contact angle further increased to 136° ± 5°, and the hexane and oil contact angles were no longer 0° (θstatic, hexane = 31° ± 5° and θstatic, oil = 49° ± 4°). Thus, omniphobicity was attained as the fabricated surface effectively prevented wetting by water as well as by low-surface-tension liquids.

In Figure 2d, to demonstrate mucoadhesion on the Carbopol side, detachment tests were conducted using porcine intestinal mucosa (see the full time-lapse photography in Figure S4, Supporting Information). An external force of 0.5 N for a contact time of 60 s was applied onto each surface as the membrane was pressed down into the tissue and then lifted to examine whether the membrane adhered to the mucosa.[27] In accordance with the manufacturing method in Figure 2a, the five membranes were examined: planar CA surface, patterned CA surface with the replicated microposts from the lotus leaf, fluorinated CA surface with the replicated microposts, omniphobic CA surface with fluorinated and lubricated microposts, and adhesive wetted Carbopol surface. All of the CA membranes – planar, patterned, fluorinated, and omniphobic – manifested no significant adhesion to the mucosa. By contrast, the Carbopol membrane when wetted readily demonstrated strong mucoadhesive behavior. Further characterization by infrared spectroscopy (Figure S5, Supporting Information) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (Figure S6, Supporting Information) illustrated differences in the chemical compositions of the modified membranes. The chemical differences were consistent with the surface modifications, where morphological changes with no chemical differences and fluorination with increased presence of tethered fluorine were confirmed. The SEM images in Figure S7 (Supporting Information) showed the morphological modifications from the initial planar surfaces of CA and Carbopol to the fabricated surfaces with omniphobicity and mucoadhesiveness, respectively.

The proposed dual-layered Janus device that demonstrates simultaneously omniphobicity and mucoadhesion was effectively constructed. The contact angle goniometry studies and the detachment tests confirmed robust omniphobicity from the CA side and strong mucoadhesiveness from the Carbopol side. Our biomimetic methodology for manufacturing the Janus device offers many favorable features, especially for scale-up and industrial applications: including inexpensive equipment, simple chemical procedure, and short fabrication time. Moreover, this manufacturing approach has the capacity to allow tunable drug-loading into the polymer during the tablet-pressing step for drug-delivery.

The modified surfaces were exposed to fluorescently-labeled bovine serum albumin (BSA) to test their protection from bio-fouling. Figure 3a shows fluorescence microscopy images of the five modified surfaces – planar CA, patterned CA, fluorinated CA, omniphobic CA, and adhesive Carbopol – after incubation with BSA for 24 h. The omniphobic coating on the CA surface significantly reduced adsorption of protein, shown by the lower fluorescence signal. In Figure 3b, the mean fluorescence intensities were calculated to quantify the protein adsorbed on the surfaces. Compared to the other four membranes, the omniphobic surface demonstrated reduced amount of protein adsorbed by about 11–17 fold. Protein adsorption studies confirmed protection and antifouling of the omniphobic side at neutral pH. Furthermore, for protection in the acidic environment of the GI tract, enteric coatings can be incorporated to the device to enable intestinal delivery.[28,29]

Figure 3.

Protein adsorption data demonstrating antifouling and ex vivo retention experiments. a) Representative microscopy images of fluorescently-labeled BSA adsorption on various modified surfaces: (from left to right) planar CA, patterned CA with microposts, fluorinated patterned CA, omniphobic patterned CA, and adhesive Carbopol. Scale bars are as shown. b) Quantitative fluorescence intensities for the corresponding modified surfaces. The mean values and standard deviations are reported (n = 8). c) Schematic representation and photograph of the experimental setup. d) The mean values and standard deviations of the retention times are reported (n = 7). Red “A” denotes adhesive and blue “O” denotes omniphobic (i.e., A|O is adhesive on one side and omniphobic on the other). e) Time-lapse photography from one of the experimental replicates. The series of the bicolored arrows traces the retention of the A|O Janus device and the series of the red arrows traces the dislodgement of the A|A non-Janus device. f) Left, a snapshot of no fouling on both devices before the flow. Right, a snapshot of no fouling on A|O Janus device (on the left with foodstuffs not adhered) versus fouling on A|A non-Janus device (on the right with foodstuffs adhered).

Using the ex vivo flow model outlined in Figure 3c (see the Experimental Section for details), retention for three different types of fabricated devices (omniphobic|adhesive, omniphobic|omniphobic, adhesive|adhesive) was assessed by measuring their dislodgement times on the excised porcine intestinal tissues.[30–32] Janus prototype devices along with bilayered adhesive and bilayered omniphobic non-Janus systems were evaluated and compared. Our retention model, designed to mimic the physiological environment of the human’s GI system, was irrigated with a simulated fed-state fluid. The irrigation media consisted of fed-state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF, pH ≈ 5.6) mixed with EnsurePlus (in a ratio of 1:4). EnsurePlus (pH ≈ 6.6) is a commercial shake that has previously been used to represent human fed gastric state, and it is composed of 29% lipids, 54% carbohydrates, and 17% proteins.[33–35] To the fluid stream, solid foodstuffs (bread and rice pieces) were also added to better approximate the GI interactions and to demonstrate potential fouling on the administered devices. Porcine intestinal tissue was chosen as the preferred substrate, as pigs have intestinal anatomy and mucus conditions similar to humans and also porcine models have previously been used in the evaluation of other GI devices.[36,37]

In Figure 3e, the time-lapse photography example collected from one of the seven replicate experiments illustrated superior retention performance of the Janus device over the non-Janus device with dual-sided adhesive. As the simulated food stream flowed over the administered devices, the Janus device (left) and the non-Janus device (right) were differentiated by the presence or absence of foodstuffs fouling on the outward surfaces of the devices (Figure 3f). For the Janus device, the omniphobic membrane minimized any undesirable interaction with the foodstuffs and the fluid stream. By contrast, the non-Janus device with the adhesive side facing outward accumulated foodstuffs on its surface, creating resistance against the fluid flow. Consequently, in terms of the retention times shown in Figure 3d, the Janus device was retained on the mucosa for a significantly longer period of time in comparison to both non-Janus devices. While the non-Janus devices became dislodged after a few seconds, dual-adhesive devices at ≈7 s and dual-omniphobic devices at ≈1 s, the Janus devices remained adherent to the mucosa for more than 10 min, at which time the measurement was stopped. Dual-omniphobic devices were non-adherent and therefore manifested in rapid transit times. Devices with dual-adhesive layers were retained, though subsequently dislodged, which is likely due to the increasing fouling on the luminal side of the device leading to greater interaction with the continuous fluid flow.

In summary, a novel Janus device with mucoadhesive and omniphobic surfaces was fabricated that effectively demonstrates the unique capacity of antifouling for extended GI retention. Using a bioinspired, facile, and low-cost manufacturing process, we incorporated strong mucoadhesion and robust omniphobicity with superb wetting resistance into our model system. This Janus system provides longer residence by the decreased interaction between the luminal-facing omniphobic side of the device and the food stream. Further preclinical development will be required for additional validation as well as identification of optimal design of the system to minimize the friction or drag encountered in the GI tract and allow enhanced drug-delivery. Additionally, our work demonstrates the capacity for tuning GI transit time by surface patterning of a dosage form. This Janus prototype opens up a broad spectrum of emerging applications, including therapeutic and diagnostic approaches that have previously been hindered by indwelling or fouling medical devices.

Experimental Section

Materials

Nanopure water was used for all aqueous sample preparations and experiments (Millipore Milli–Q Reference Ultrapure Water Purification System, 18.2 MΩ cm). Acetone (AR, ACS grade) was purchased from Macron Fine Chemicals (Center Valley, PA). For the molding method, Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit was used with the base and the curing agent purchased from Dow Corning (Midland, MI). Fresh lotus leaves were acquired from a local company called Wonderful Water Lilies (Sarasota, FL). Cellulose acetate (MW ~ 30,000 Da) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). For constructing omniphobic membranes, heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrodecyl trichlorosilane was purchased from Gelest, Inc. (Morrisville, PA) and perfluorodecalin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For adhesive membranes, Carbopol 934 was purchased from Lubrizol (Wickliffe, OH). For contact angle analysis, vegetable oil was purchased from a local store and hexane (Macron Fine Chemicals, AR, ACS grade), ethanol (Koptec, King of Prussia, PA, 200 proof, 99.5%), and toluene (Sigma-Aldrich, anhydrous, 99.8%) were used. Albumin from bovine serum (BSA)-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). Potassium chloride (KCl), acetic acid, sodium taurocholate, lecithin, and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Fed-state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF) was made using 15.2 g L−1 of KCl, 8.65 g L−1 of acetic acid, 15 mM of sodium taurocholate, and 3.75 mM of lecithin, and was adjusted to pH ~ 5.6 by NaOH and water.[38] EnsurePlus (Abbott Laboratories B.V., Zwolle, the Netherlands) was purchased from a local store. All chemicals were used as received unless otherwise specified. Pig tissues were procured from a local slaughterhouse (Research 87) in Massachusetts. All tissues were collected within 2 hours of the animal being sacrificed and kept at 4 °C for as long as 7 days. All animal tissue procedures were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Committee on Animal Care.

Manufacturing of lotus leaf polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold

The acquired fresh lotus leaf was cut into a small piece, rinsed with nanopure water, and dried with nitrogen gas. The leaf piece was glued down to a plate with the upper leaf side facing outward. PDMS pre-polymer solution was made with 10:1 ratio of Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer base and curing agent. The PDMS solution was placed in a vacuum desiccator for approximately an hour to eliminate air bubbles. The solution was poured onto the plate with the leaf taped down on the bottom. The mold was placed in a vacuum oven at 40 °C overnight. Then the mold was placed at room temperature for an hour to cool down before it was peeled off from the leaf.

Fabrication of Janus device

In 1:1 ratio of ~300 mg each, the powder forms of Carbopol polymer and of cellulose acetate (CA) polymer were tablet-pressed at 20 MPa, one layer on top of the other, into a dual-layered thin tablet. YLJ-24T Desk-Top Powder Presser purchased from MTI Corporation was used. A droplet of acetone was pipetted onto the surface of the CA layer. The tablet was quickly pressed onto the PDMS lotus leaf master mold with the wetted CA layer facing down onto the mold. The tablet was pressed down for approximately 15 minutes until the acetone evaporated away, and then the tablet was detached from the PDMS mold. With the CA side facing up, the tablet was placed in a vacuum desiccator for overnight with 0.2 mL of heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrodecyl trichlorosilane in a glass vial for fluorination. Then the perfluorodecalin was pipetted over the fluorinated CA surface to create a lubricating film locked within the microposts.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the fabricated surfaces was observed using the JEOL 5600LV SEM located in the facilities at MIT Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts. For nano-scale visualization, Zeiss Merlin High-resolution SEM at MIT Center for Materials Science and Engineering was used. Before visualization under SEM, all samples were sputter-coated with carbon using the Hummer 6.2 Sputter Coating System. Samples were cut to be under 0.5 cm2 in area and fixed to the aluminum stubs by a double-sided adhesive carbon conductive tape.

Contact angle goniometry

The wetting of the fabricated surfaces was characterized by static contact angle measurements using the Krüss Drop Shape Analyzer DSA100 with the software Drop Shape Analyzer (Matthews, NC). Contact angles with various liquids (water, vegetable oil, hexane, ethanol, and toluene) over the sample surface, fixed to lay flat on a horizontal plane, were measured at room temperature. A fixed volume of 250 μL droplet of the chosen liquid was dispensed onto the substrate, and the contact angle made between the line tangent to the liquid droplet and the substrate surface was measured. The macroscopic droplet profile was photographed by a camera installed within the instrument. The mean and the standard deviation values for each surface were calculated and reported from eight measurements.

Detachment tests

A segment of porcine intestinal tissue was placed onto a bottom platform with the mucosal side facing up, and a test membrane was fixed onto the upper platform with the modified side facing down. An external force of 0.5 N for contact time of 60 seconds was applied onto each surface as the membrane was pressed down into the tissue and then lifted up at the rate of 0.5 mm min−1 to examine whether the membrane adhered to the mucosa. Using a digital camera, sequential photographs were collected.

Infrared spectroscopy (IR)

IR spectra were recorded on the ALPHA FT-IR Spectrometer (Bruker Corporation) and analyzed using the OPUS v. 6.5.92 software. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS): XPS analysis was performed using the PHI VersaProbe II (Physical Electronics) at MIT Centre for Materials Science and Engineering (CMSE). The instrument, equipped with a monochromatic aluminum X-ray source, was operated with the pass energy of 187.85 eV and chamber pressure under 2 × 10−9 Torr during the analysis. Photoelectrons were collected at an angle of 45.0° from the surface normal. Samples were dehydrated through lyophilization overnight. Upon removal from the lyophilizer, samples were transported to the XPS equipment in a vacuum desiccator and analyzed immediately.

Protein adsorption studies

1 mg/ml BSA-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate was dissolved in PBS at pH 7.4. Samples of a defined size (0.5 cm2) were incubated in 300 μL of fluorescently-labeled BSA solution for 24 hours at 37 °C.[39] The samples were rinsed five times with PBS and observed under a fluorescence microscope (EVOS) at 2× magnification. Captured images were analyzed and quantified based on the mean fluorescence intensity using the image-processing software ImageJ (NIH). All intensities were corrected to that emitted from the negative control for each corresponding modified surfaces. The mean and the standard deviation values for each surface were calculated and reported from eight replicates.

Ex vivo studies

The prior tissue flow binding setup was modified as follows for evaluation of our devices.[40] A flow model apparatus (shown in Figure 3a) was built to examine the retention profiles of the fabricated devices. Excised porcine intestinal tissues were cut into a length of 30 cm and opened to line the slide of the apparatus. With the detachable slide from the apparatus laid flat, a Janus device and a non-Janus device were placed on the tissue, at 22 cm from the bottom of the slide. They were incubated at room temperature for 30 seconds allowing the Carbopol polymer to adhere to the mucosa through hydration. The slide was turned upside down to ensure that the devices had adhered and was put back to the apparatus at a tilt angle of 30°. At room temperature, the fixed mucosal intestinal tissue was continuously flushed with simulated fed-state fluid at 850 mL min−1. The flow rate was selected based on the range of transit times for fluids in the GI tract; with the intestinal transit time for fed-state being approximately 2–3 mL min−1[41] and the esophageal transit time being around 700–800 mL min−1, [42,43] a value near the upper boundary was selected to simulate the maximal physiological stress. The simulated fluid consisted of fed-state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF, pH ~ 6.8) and EnsurePlus (pH ~ 6.6) in a ratio of 1:4 with foodstuffs (15 g L−1 of bread pieces and 50 g L−1 of rice) mixed in. The times for dislodgment were documented and compared for the different fabricated devices. Video was recorded with a digital camera and sequential photographs from the video recordings were collected. The retention studies for the three types of fabricated devices (omniphobic|adhesive, omniphobic|omniphobic, adhesive|adhesive) were performed in seven replicates each, using fresh intestinal tissue piece at each trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Y.-A.L.L., S.Z., R.L., and G.T. designed the device and the experiments. Y.-A.L.L. prepared the materials and the device. Y.-A.L.L., S.Z., J.L., and G.T. characterized the materials, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. R.L. and G.T. supervised the research. All authors discussed the progress of research and reviewed the manuscript. This work was sponsored in part by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Grant OPP1096734 (to R.L.) and NIH Grant EB000244 (to R.L.) as well as the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation under the auspices of the Max Planck Research Award to R.L. funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Y.-A.L.L. was supported in part by the Jerome A. Schiff Fellowship. The authors would like to thank Nolan Flynn for his help in manuscript preparation. The findings and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Young-Ah Lucy Lee, Department of Chemical Engineering and Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Dr. Shiyi Zhang, Department of Chemical Engineering and Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

Dr. Jiaqi Lin, Department of Chemical Engineering and Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

Prof. Robert Langer, Department of Chemical Engineering and Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139, USA Harvard–MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology Institute of Technology, Massachusetts, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Dr. Giovanni Traverso, Department of Chemical Engineering and Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139, USA Division of Gastroenterology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

References

- 1.Croisier F, Jérôme C. Eur Polym J. 2013;49:780. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun T, Qing G. Adv Mater. 2011;23:H57. doi: 10.1002/adma.201004326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ngoepe M, Choonara Y, Tyagi C, Tomar L, du Toit L, Kumar P, Ndesendo V, Pillay V. Sensors. 2013;13:7680. doi: 10.3390/s130607680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khutoryanskiy VV. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11:748. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaikh R, Raj Singh TR, Garland MJ, Woolfson AD, Donnelly RF. J Pharm BioAllied Sci. 2011;3:89. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.76478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peppas NA, Sahlin JJ. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1553. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)00307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boddupalli BM, Mohammed ZNK, Nath RA, Banji D. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2010;1:381. doi: 10.4103/0110-5558.76436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Blevins WE, Park H, Park K. J Controlled Release. 2000;64:39. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peppas NA, Hilt JZ, Khademhosseini A, Langer R. Adv Mater. 2006;18:1345. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaghloul A, Taha E, Afouna M, Khattab I, Nazzal S. Die Pharmazie. 2007;62:346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chirra HD, Desai TA. Small. 2012;8:3839. doi: 10.1002/smll.201201367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pizzi A, Mittal KL. Handbook of Adhesive Technology, Revised and Expanded. Taylor & Francis; Abingdon, UK: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ainslie KM, Desai TA. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1864. doi: 10.1039/b806446f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chirra HD, Desai TA. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2012;64:1569. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peppas NA, Thomas JB, McGinty J. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2009;20:1. doi: 10.1163/156856208X393464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bixler GD, Bhushan B. Philos Trans R Soc, A. 2012;370:2381. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuzzo RG. Nat Mater. 2003;2:207. doi: 10.1038/nmat872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizrahi B, Khoo X, Chiang HH, Sher KJ, Feldman RG, Lee JJ, Irusta S, Kohane DS. Langmuir. 2013;29:10087. doi: 10.1021/la4014575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walther A, Müller AHE. Chem Rev. 2013;113:5194. doi: 10.1021/cr300089t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaewsaneha C, Tangboriboonrat P, Polpanich D, Eissa M, Elaissari A. ACS Appl Mater Interf. 2013;5:1857. doi: 10.1021/am302528g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong TS, Kang SH, Tang SK, Smythe EJ, Hatton BD, Grinthal A, Aizenberg J. Nature. 2011;477:443. doi: 10.1038/nature10447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepore E, Pugno N. BioNanoSci. 2011;1:136. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S, Liu K, Yao X, Jiang L. Chem Rev. 2015;115:8230. doi: 10.1021/cr400083y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leslie DC, Waterhouse A, Berthet JB, Valentin TM, Watters AL, Jain A, Kim P, Hatton BD, Nedder A, Donovan K, Super EH, Howell C, Johnson CP, Vu TL, Bolgen DE, Rifai S, Hansen AR, Aizenberg M, Super M, Aizenberg J, Ingber DE. Nat Biotech. 2014;32:1134. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ensikat HJ, Ditsche-Kuru P, Neinhuis C, Barthlott W. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2011;2:152. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.2.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiorth M, Nilsen S, Tho I. Pharmaceutics. 2014;6:494. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics6030494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lappas LC, McKeehan KW. J Pharm Sci. 1962;51:808. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600510828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siepmann F, Siepmann J, Walther M, MacRae RJ, Bodmeier R. J Controlled Release. 2008;125:1. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajput P, Singh D, Pathak K. Int J Pharm. 2014;461:310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vyas SP, Talwar N, Karajgi JS, Jain NK. J Controlled Release. 1993;23:231. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhaliwal S, Jain S, Singh HP, Tiwary AK. AAPS J. 2008;10:322. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmstock N, Bruyn TD, Bevernage J, Annaert P, Mols R, Tack J, Augustijns P. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;49:27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein S. AAPS J. 2010;12:397. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9203-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mudie DM, Amidon GL, Amidon GE. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2010;7:1388. doi: 10.1021/mp100149j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swindle MM, Makin A, Herron AJ, Clubb FJ, Jr, Frazier KS. Vet Pathol. 2012;49:344. doi: 10.1177/0300985811402846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guilloteau P, Zabielski R, Hammon HM, Metges CC. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23:4. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galia E, Nicolaides E, Hörter D, Löbenberg R, Reppas C, Dressman JB. Pharm Res. 1998;15:698. doi: 10.1023/a:1011910801212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farrell M, Beaudoin S. Colloids Surf, B. 2010;81:468. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dhaliwal S, Jain S, Singh HP, Tiwary AK. AAPS J. 2008;10:322. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mudie DM, Amidon GL, Amidon GE. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2010;7:1388. doi: 10.1021/mp100149j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cordova-Farga T, Sosa M, Wiechers C, De la Roca-Chiapas JM, Maldonado Moreles A, Bernal-Alvarado J, Huerta-Franco R. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5707. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones DV, Work CE. Am J Dis Child. 1961;10:427. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1961.02080010429023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.