Abstract

Certain types of pain are major unmet medical needs that affect more than 8 percent of the population. Neuropathic pain can be caused by many pathogenic processes including injury, autoimmune disease, neurological disease, endocrine dysfunction, infection, toxin exposure, and substance abuse and is frequently resistant to available pain therapies. The same can be said of postsurgical pain, which can arise from uncontrolled inflammation around the wound site. The complement system is part of the innate immune system and can both initiate and sustain acute and chronic inflammatory pain. Here we review the complement system and original investigations that identify potential drug targets within this system. Drugs that act to inhibit the complement system could fill major gaps in our current standard of care for neuropathic pain states.

Keywords: Complement, Complement inhibition, Neuropathic pain, Post-operative pain

INTRODUCTION

Neuropathic pain affects more than 8 percent of the population [1]. Many disparate sources can cause neuropathic pain, such as diabetes, herpes varicella, multiple sclerosis, cancer, surgery, and spinal cord injury. Neuropathic pain states represent a major unmet medical need because they are frequently resistant to the available pain therapies. Although some relief can be afforded by tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, or anti-epileptics [2] no current therapy provides more than 50% relief in the clinic. Inflammation is a key driver of neuropathic and postoperative pain. The complement cascade initiates the inflammatory response, but it has been largely neglected in the development of treatments for inflammatory pain. Considerable scientific evidence, however, supports a major role of the complement system in pain. The paucity of original investigations in the literature suggests that complement inhibition has been for the most part overlooked and thus could be a first in class opportunity for severe pain, and could fill major gaps in the current standard of care. Here we briefly review the complement system and then summarize experimental data on its role in neuropathic pain.

THE MAMMALIAN COMPLEMENT SYSTEM

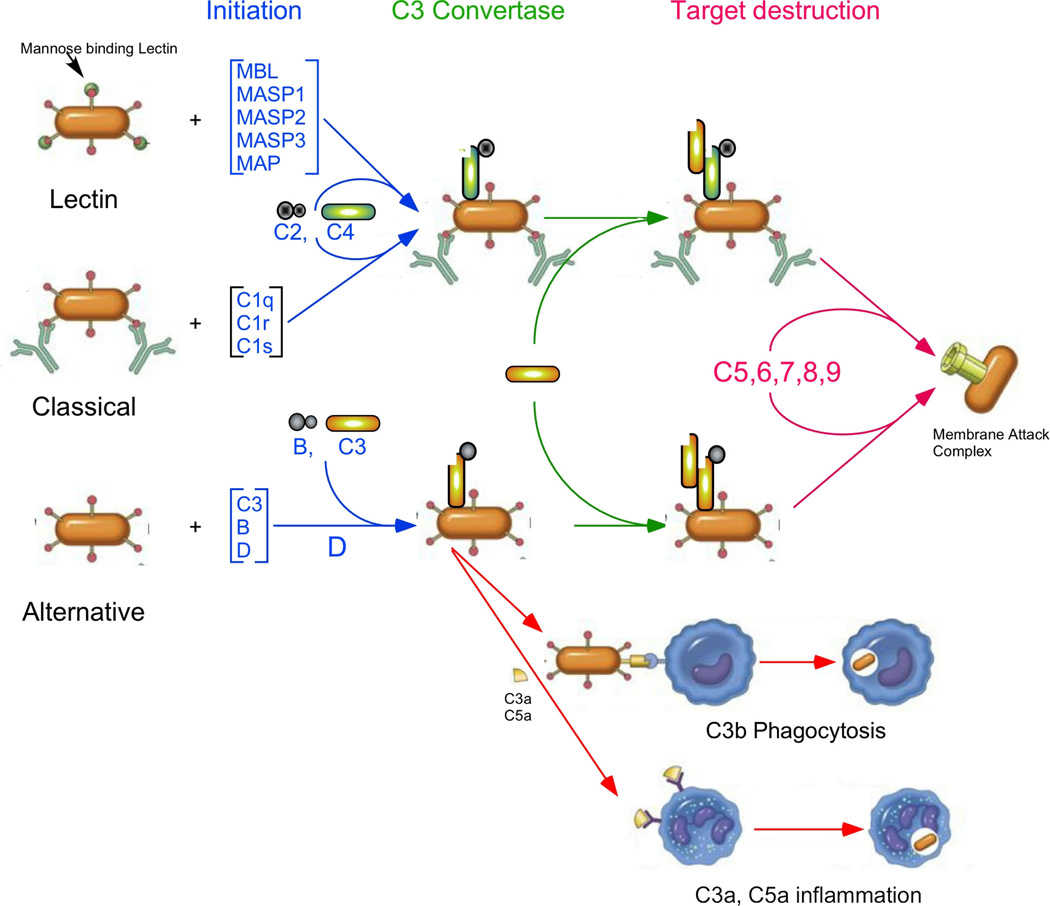

The complement system is an important part of the innate immune system, which helps to protect the host against infection and provides a connection between the innate and adaptive immune systems. Complement consists of more than 30 proteins, found both in the fluid phase and on cell surfaces. It is activated through a series of proteolytic cleavages, which activate proteins in the next step of the complement cascade (Fig. 1). There are three complement activation pathways, the Classical, activated by the presence of antibodies on a cell surface, the Lectin pathway, activated by the recognition of certain carbohydrates on cell surfaces, and the Alternative pathway, which is constantly being activated by a slow, spontaneous conformational change in the most abundant complement protein, C3. All three activation pathways come together with activation of C3 on a cell surface. This, in turn, allows for the activation of another complement protein, C5, that initiates the terminal complement pathway that forms the macromolecular Membrane Attack Complex (MAC), which is able to destroy invading pathogens by punching holes in their cellular membrane [3 – 8].

Fig. (1).

Complement activation pathways, showing final activation products, such as C3b (or C3dg) on cell surfaces, the Membrane Attack Complex (MAC) and the anaphylatoxins produced during complement activation. The three activation pathways (blue) meet at the C3 activation step (green), where the activated C3 is bound covalently on the target cell surface. Complement activation can cause pain in three ways (red). First, the MAC can lyse cells. Second, cells with bound C3b (or C3dg) are targeted for phagocytosis. Finally, the anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a can bind to their receptors (C3aR and C5aR, respectively), attracting macrophages which cause inflammation.

In the Classical activation pathway of complement [9], the C1 complex, containing one C1q and two molecules each of the serine proteases C1s and C1r, recognizes an antibody bound to a cell surface. Once the C1 complex is bound to the cell surface, the proteases are activated and are able to cleave another complement protein, C4 into the anaphylatoxin C4a and C4b. This cleavage causes a large conformational change in C4b, allowing it to covalently bind to cell surfaces and bind another complement protein, C2. C2 is then cleaved into the activation peptide, C2b, and the protease containing C2a. The complex of C4b and C2a (C4b2a) is a serine protease that specifically cleaves C3 into the anaphylatoxin C3a and the active form of C3, C3b, which is then able to covalently bind to the cell surfaces.

The Lectin pathway [10] is similar to the Classical pathway in that it is activated by the binding of a protein to cell surfaces, in this case, mannose binding lectin (MBL) onto mannose residues that are often found on the cell surface of bacteria. Similar to the Classical pathway, the binding of MBL to mannose on cell surfaces activates three proteases bound to MBL, MASP1, MASP2, and MASP3. Like C1r and C1s, the MASPs are serine proteases that are able to activate C4 and C2, which are then able to activate C3.

The Alternative pathway [11] acts somewhat differently, in that its activation is caused by the constant, slow activation of C3 in the fluid phase. C3 activation is caused by the breaking of a high energy intramolecular bond called the thioester linkage. The breaking of the thioester linkage allows a large conformational change in C3 that exposes several protein binding sites on the protein surface and allows the product of this spontaneous activation, C3(H2O) to covalently bind to cell surfaces. The product of the spontaneous activation of C3 is called C3(H2O). C3(H2O) is able to bind another complement protein, factor B, which is then cleaved by factor D, resulting in an enzyme, C3 convertase, that is able to activate other C3 proteins by clipping off the 77 amino acid anaphylatoxin, C3a, from the active form of C3, C3b. C3b can covalently bind to the cell surface (through the now broken thioester linkage) and is then able to act in an identical manner as C3(H2O), binding factor B, which is then cleaved by factor D to form the C3 convertase, C3bBb.

All the activation pathways result in active C3b on the cell surface, and allows the formation of a patch of active C3 convertases. Eventually, some of the convertases will bind an additional C3b, which allows them to cleave C5, into the anaphylatoxin C5a and C5b. C5b can then bind other complement proteins, C6, C7, C8 and multiple copies of C9, forming the MAC. C5a (and to a lesser extent, C3a and C4a) is a powerful anaphylatoxin that is able to increase vascular permeability, cause smooth muscle contraction, histamine release, and mediate chemotaxis and inflammation [7, 12]. The pathways of complement activation are shown in Fig. (1).

Since complement is continuously being activated, there needs to be a way to control complement activation. This is done by a number of other complement proteins. For example, in the fluid phase, factor H can bind to C3b, preventing the formation of the C3 convertase. Once bound to see C3b, factor H serves as a co-factor, allowing another compliment protein, factor I, to cleave C3b, thus inactivating it. There are also a number of cell bound proteins that are able to regulate complement activation.

The complement system is ancient, and portions of it, namely C3-like proteins and their activators, are found in animals as primitive as Cephalochordata, Urochordatra, Echinochordata, and Cnardarian anghrozoans [13, 14]. The presence of C3-like proteins in these organisms suggests that the Alternative pathway may be the most ancient. It is likely that the lectin pathway evolved more recently, and the classical pathway evolved in more advanced vertebrates (bony fish, etc.), where the adaptive immune system is present [15].

THE COMPLEMENT SYSTEM AND PAIN (SUMMARIZED IN TABLE 1)

Table 1.

Summary of cited studies on the role of complement in experimental and disease-related pain.

| Pain Model | Organism | Experimental Endpoints Measured/span> |

Anti Complement Agent |

Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid Pain Relief | Mice | Anti-analgesic effect | C3a | C3a reduces the analgesic effect on mice treated with opioid pain medication |

[27, 28] |

| Sciatic Nerve Ligation | Rat | Mechanical Allodynia Cold Allodynia |

C5aR antagonist AcF- [OPdChaWR] |

Less mechanical and cold allodynia in mice treated with C5aR antagonist |

[38] |

| C6 (−/−) rats | Mechanical Allodynia Cold Allodynia |

NA | Normal neuropathic pain phenotype, MAC not involved |

||

| Sciatic Nerve Ligation | Rat | Mechanical hyperalgesia | CVF | Complement depletion reduces pain behavior | [26] |

| Sciatic Nerve Ligation | Rat | Thermal Hyperalgesia Mechanical Allodynia |

Soluble Complement receptor (sCR1) |

C3 deposition seen after SCL and IgG injection, accompanied by macrophage recruitment. sCR1 Injections resulted in less TH and MA. |

[25] |

| Spinal inflammatory Neuropathy Caused by Zymosan, GP120, and chronic constriction injury |

Rat | Mechanical Allodynia | sCR1 | sCR1 injection reduces mechanical allodynia. | [23] |

| Sciatic Nerve Crush | Rat | Macrophage infiltration and activation |

Conmplement inhibitor: Cobra Venom Factor (CVF) |

Less macrophage infiltration in CVF-treated animals. |

[20] |

| Sciatic Nerve Chronic constriction injury |

Mouse | Hyperalgesia | CVF | Mice given daily injections of CVF had less hyperalgesia. 1 CVF injection 4 days after surgery greatly reduced hyperalgesia. |

[30] |

| Paw Incision | Mouse | Incisional Allodynia and Edema |

AcF-[OPdChaWR] | Daily injection of AcF-[OPdChaWR] reduces incisional edema and allodynia. |

[35] |

| Paw injection | Mouse | Heat and Mechanical Hyperalgesia |

NA | C5a injection elicits both heat and mechanical hyperalgesia, while C3a injection elicits only mechanical hyperalgesia |

[45] |

| Paw injection | Mouse | Heat Hyperalgesia and Mechanical Allodynia |

PMX53 (C5aR antagonist) |

Injection of PMX53 reduces both heat hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia caused by injection of C5a |

[46] |

| Paw Injection | Rat | Edema | Vinblastine | C5a -induced hypernociception reduced when neutraphils reduced by vinblastin treatment. |

[43] |

| Hypernociception caused by injection of zymosan, carrageenan, LPS, and antigen. |

PMX53 | PMX53 injection reduced hypernociception. | |||

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Human | C5a | NA | C5a levels increased in rheumatoid joint fluids. Neutraphils increased in synovial fluid. |

[53] |

| Sickle Cell Anemia | Human | Pain, C3a, C3, Bb, C4d, | NA | Measured complement levels in patients suffering severe painful episodes vs. base levels. Complement activation was higher during painful episodes. |

[24] |

| C5a Injection into hindpaw |

Rat | Nociception | Hydroxyurea | C5a is a chemotactic peptide, and injection into hindpaw of rats induces hyperalgesia. In addition, PML supernatant also causes hyperalgesia. When PMLs reduced by hydroxyurea treatment, hyperalgesia reduced. |

[33] |

| anti-ganglioside GD2 antibody-induced pain |

Rat | Hindpaw allodynia | Non complement-fixing antibody GD2 antibody |

Mice treated with mutant antibody with reduced CDC activity had faster resolving allodynia than those injected with "normal" antibody. C6 knockout mice had reduced allodynia, while C5aR antagonist eliminated allodynia. |

[47] |

| C5a receptor knockout | Mouse | Pain, edema | C5aR knockout vs. normal. |

In C5aR−/− mice, thermal nociceptive pain reduced for 4 days post-incision, while mechanical sensitivity reduced only after 48 hrs. C5aR−/− showed little edema, while wt mice showed normal edema. |

[37] |

| Hematuria/Groin Pain | Human | C3b | NA | Patients with loin pain and Haematuria had C3b deposition on arteriolar walls. |

[16] |

| Spinal Cord Injury | Rat | Macrophages | Vaccinia Virus Complement Control Protein (VCP) |

VCP injection following spinal cord injury inhibits macrophage infiltration and improves hind limb function. |

[17] |

| CFA and C5a injection | Mice | Threshold of pain | PMX53, knockout mice | Showed that pain is mediated by activation of TRPV1 ion channels. NGF is one activator of TRPV1. |

[49] |

| Inflammatory and neuropathic pain |

Mice | Hyperalgesia | DF2593A | Showed injection of mice with DF2593A reduces inflammatory and neuropathic pain |

[52] |

A correlation of complement activation with pain was first seen by Naish et al. (1975) [16] who noticed that C3 (most likely C3b) deposition was seen in the kidneys of patients suffering from loin pain and haematuria. There was no difference in the amount of C3 in the blood between normal and patients with loin pain, and no deposition of other complement components, including C1q, C4, C5 and Bb was seen.

There have been several later studies showing that complement activation, in general, can be associated with pain. Reynolds and collaborators [17] used injection of vaccinia complement control (VCP) protein to examine the effect of complement activation on animals with spinal cord injuries (SCI). VCP blocks all the complement activation pathways early in the cascade, and prevents the activation of C3, C4, and C5, thus preventing formation of the anaphylatoxins C3a, C4a, and C5a [18]. Their results showed that compared to untreated animals subjected to spinal cord injury, VCP+ animals showed less macrophage migration to the site of the injury 14 days after the injury, though the animals treated with VCP did show more macrophages at the site of the injury after 7 days. They also found that VCP-treated animals had better motor function than untreated animals in an open-field locomotion study, though the difference was not significant. Using a grid-walking test (measuring how many times one of the rear paws fell through the grid), VCP-treated animals showed significantly better motor function. Their explanation for the discrepancy in results of two different motor function tests was that the grid-walking test is more quantitative, and the field-locomotion test is more subjective and harder to score accurately. While this study did not specifically discuss the contribution of complement activation to pain, it does show that blocking the complement cascade does decrease the number of macrophages at the site of SCI after 14 days. Since macrophage infiltration has been associated with pain [19], these data are consistent with a role for complement in pain.

Dailey and coworkers [20] were also able to show the role of complement activation in recruiting macrophages. In their study, they used cobra venom factor (CVF) [21] to deplete the animals of complement. CVF, an analog of C3b, is able to form a stable C3 convertase, which is also resistant to complement control proteins like factors H and I. The CVF-containing convertase continuously activates C3 by cleaving C3 into two parts, the anaphylatoxin C3a and the active form of C3, C3b. C3b is able to form a C3 convertase, which is subject to regulation by complement control proteins, which are able to inactivate C3b, thereby blocking all three activation pathways at the C3b formation step [22]. They showed that fewer macrophages were recruited to the site of the injury, and that the injury was slower to heal, as measured by staining for neurofilament regeneration seen after 4 and 7 days post injury, thus demonstrating that complement activation plays a role in macrophage recruitment and regeneration of nerve damage following sciatic nerve crush. In addition, since it has been shown that inflammation and macrophage recruitment both play a role in neuropathic pain [19], these data also are consistent with complement activation playing a role in neuropathic pain.

Soluble Complement Receptor 1 (sCR1) inhibits the complement activation cascades by binding both C3b and C4b. Twining and coworkers [23] have shown that intrathecal injection (into the spinal cord) of sCR1 reduces mechanical allodynia in three different models of enhanced nociception of the spinal cord. These include sciatic inflammatory neuropathy, partial sciatic nerve injury (chronic constriction injury) and injection with HIV gp120. Intrathecal sCR1 had no effect on the behavioral responses of control mice, but mechanical allodynia induced by sciatic nerve injury, chronic constrictive nerve injury or HIV1 protein GP120 injection were completely abolished. Since the enhanced nociception was prevented or reversed in all three situations, it is suggested that complement is broadly involved in spinally-mediated pain enhancement.

A study of episodic and chronic pain in patients with sickle cell anemia by Mold and coworkers [24] provides more evidence that complement activation can lead to pain. Levels of complement “split products” (Bb, C4d, C3a, and C3b/C3d bound to erythrocytes) were measured in patients with episodic sickle cell crisis, both as outpatients, when pain levels were low, and as inpatients, when pain levels were high. Increased levels of the complement components listed above were seen for episodic patients during crisis. In patients with chronic pain from sickle cell anemia, complement levels were high, but did not significantly change between their being inpatients and outpatients. Since increased complement activity was seen in patients suffering pain, increased complement activation was correlated with pain in these patients.

Li and coworkers [25] demonstrated that partial sciatic nerve ligation activated complement. After ligation, C3 deposition was seen at the injury site, as well as in areas near the injury site, while no deposition was seen on sham-operated animals (no partial ligation). Increased heat-related hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia was also seen on the on nerve-injured side. Injection of IgG, which also activates complement, into the paws of rats caused neuropathic pain symptoms. Activation of complement also increased the influx of macrophages. To further test the role of complement activation in pain, rats were injected IP with sCR1 15 minutes prior to partial ligation surgery, and then tested for heat and mechanical sensitivity. Rats injected with sCR1 showed significantly higher pain thresholds than those that were sham injected. These rats also showed less C3 deposition and macrophage influx. From these results, they suggested that increased hyperalgesia and allodynia may be associated with local complement activation, and the resulting macrophages present in damaged tissue.

A somewhat different approach was taken by Levin et al. [26], who used expression screening to determine which genes were up and down regulated in a spinal ligation model of neuropathic pain. A genome-wide screen showed that several complement-related genes were significantly up regulated, including C1q, C1Inh, C1r, C1s, C3, C4, C5, properdin, and factors B and D, while Decay Activating Factor (DAF, a cell surface complement regulatory protein) was down regulated. They also were able to show that complement is activated both in the peripheral nerves and the CNS during neuropathic pain. Immuohistochemical and in situ hybridization data from the dorsal root ganglia showed increased C3 mRNA and C3b protein, and deceased DAF mRNA and protein. Decreases in DAF were associated with the neurons, while increases in C3 mRNA were in satellite cells that appeared to be microglia or macrophage-like. C3b protein was increased around select satellite cells, and on the surface of the neurons, suggesting that C3 was released from the satellite cells and then activated and bound to the neuronal membranes. Depletion of complement by ip injection of CVF not only reduced serum complement levels, but also decreased neuropathic pain, as measured in a paw-withdrawal assay. The CVF produced analgesia starting on day 3, reached significance on days 5 and 6. After day 8 following spinal ligation, the CVF had no effect, which is not surprising considering that CVF residence time in animals is only about 5 to 6 days. This loss of efficacy could be explained by immunogenicity, but was not further addressed.

The role of complement C3a in pain was investigated by Jinsmaa and colleagues [27, 28]. Administration of complement C3a into the cerebral ventricles of mice inhibited analgesia induced by morphine. The kappa opioid agonist U-50488H produced analgesia in the hotplate and the tail pinch tests after systemic injection (30 mg/kg subcutaneous). The analgesic effect of U-50488H was completely reversed by the intracerebroventricular (ICV) administration of C3a at 10, but not 3 pmoles. Drugs acting at the delta opioid receptor produce robust analgesic effects [29]. Analgesia was observed by Jinsmaa and colleagues when mice were injected with 3 pmoles (ICV) of the selective delta receptor agonist peptide DTLET (Tyr-D-Thr-Gly-Phe-Leu-Thr), but this effect was not antagonized by C3a at doses up to 10 pmoles ICV. The selectivity for mu (morphine) and kappa (U-50488H) over delta (DTLET) receptors demonstrates that the effect of C3a was specific. It was later demonstrated [28] that a C3a fragment (YPLPR) could bind to the mu opioid in addition to the C3a receptor. The tyrosine variant of this peptide (WPLPR), however, could still reverse opioid analgesic effects despite its complete absence of affinity for the opioid receptor. This suggests a direct effect of theC3a receptor to block endogenous analgesic activity, and that a selective C3a antagonist might have novel and useful analgesic properties.

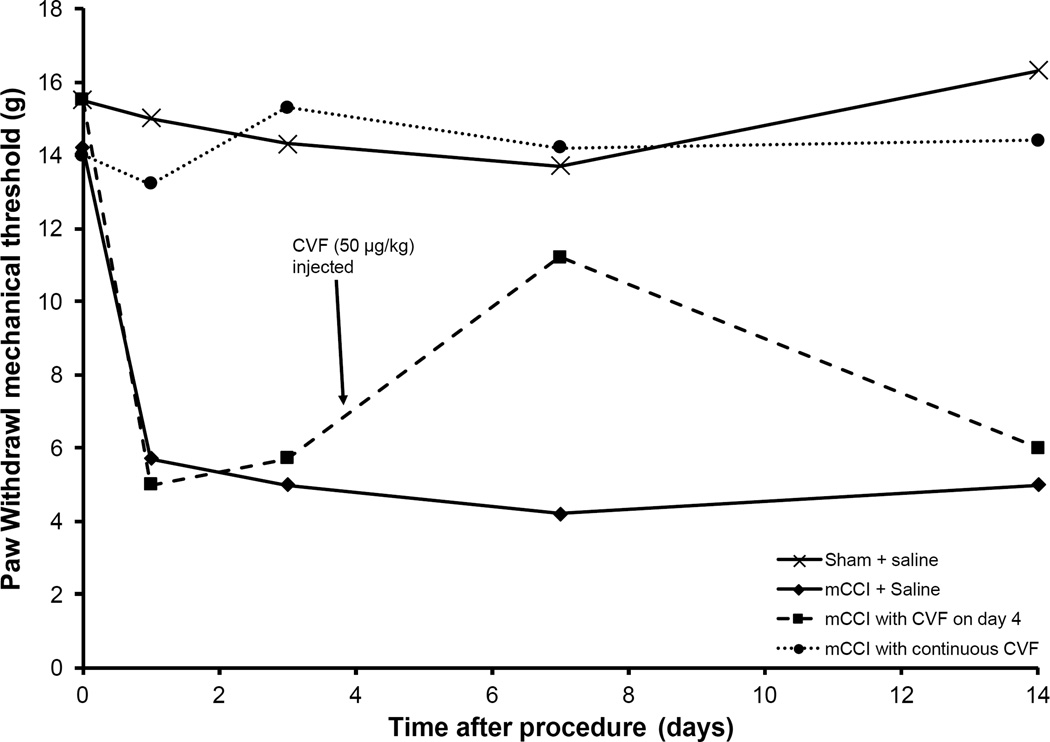

Complement depletion with CVF was also used to examine the role of complement in pain caused by a modified chronic constriction injury (mCCI) model of neuropathic pain from nerve injury [30]. The authors noted that mCCI caused an increase in both C3 protein and mRNA levels in the spinal cord of mCCI rats. Injection of CVF into mCCI rats raised the thresholds of thermalglesia and hyperalgesia, again demonstrating the role of complement activation in pain. Most notably, a single CVF injection on day 4 (in rats that had previously not been injected with CVF) showed a temporary decrease in pain sensitivity, lasting for several days (Fig. 2).

Fig. (2).

Effect of complement depletion by CVF on hyperalgesia in rats following sciatic nerve ligation. Sham treated rats (no nerve ligation) showed no increase in pain sensitivity. Sciatic nerve ligation followed by saline injections showed a significant increase in pain sensitivity through the course of the experiment. Pain sensitivity in rats treated with CVF before and after surgery was essentially identical to untreated rats, while injection of CVF into saline-treated rats on day 4 showed a decrease in hyperalgesia lasting at least 3 days. (Data from: Nie et al., 2007 and printed with the permission of the author.)

ROLE OF C5a IN INFLAMATION AND PAIN

The papers described above demonstrate that complement activation plays a major role in pain. However, they do not attempt to determine which complement components may be responsible. It has been shown that pain can result from inflammation [19], and that the influx of neutrophils and other inflammatory cells plays a role in inflammation [8]. In the complement system, the strongest attractant for neutrophils is the anaphylatoxin C5a [31]. For these reasons, there have been a number of studies where the role of C5a, and its receptor C5aR have been studied to look into their role in pain that results from complement activation. This topic was also extensively covered in a recent review by Quadros and Cunha [32].

The first observation of a relationship of C5a and pain in animals was by Levine and coworkers [33]. In this study, the authors noted that injecting C5a into the hind paws of rats lowered their threshold of pain by more than 20%.They also noted that injecting hydroxyurea, which greatly reduces polymorphic lymphocyte migration [34] raised the pain threshold of rats whose hind paws had been injected with C5a.

Following hindpaw incision in the mouse, C5a receptor mRNA increased 15-fold in the surrounding skin [35] and a multiplexed assay showed increases in 8 of 18 cytokines measured. Daily injection with a C5a receptor antagonist AcF-[POdChaWR] [36] prevented the increase in 7 of the 8 cytokines that responded, suggesting that complement inhibition or depletion could be useful to reduce the pain and swelling of surgical incisions. Injection of AcF-[POdChaWR] into the animals reduced the nociceptive pain threshold to baseline after 24 hours, while the threshold didn’t return to baseline until 96 hours in untreated animals. Treated animals also showed less edema than untreated. In another study of postsurgical pain, Liang et al. [37] used C5a receptor knockout mice to study heat hyperalgesia, mechanical allodynia, and edema in a hindpaw incision model. Responses to painful stimuli were measured for 4 days after the incision. They found that heat hyperalgesia was significantly reduced throughout the post-incision period, but mechanical sensitization was only reduced at the later time points. Interestingly, edema developed after the incision in the wild-type mice, but only slightly and transiently in the C5aR knockout mice. These findings support the contention that the complement system is a novel and valid target for the control of pain and inflammation after surgery.

A study by Griffin and coworkers [38] used microarrays to study gene regulation in three models of neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve damage, the spared nerve injury model [39], the chronic constriction injury model [40], and the spinal nerve ligation model [41]. They found the expression of 54 genes increased in all three models, including the complement related genes C1q, C3, C4 in the dorsal horn after nerve injury. This increase in expression was found only in microglial cells. They also found increased expression of C5 and C5aR after spared nerve injury in the microglia. The authors also used the C5aR antagonist AcF-[OPdChaWR] to examine the role of C5a in pain, and found that mice injected with both C5a and AcF-[OPdChaWR] showed less cold allodynia than mice injected with C5a and PBS. Finally, to see if MAC formation played a role in neuropathic pain after spared nerve injury, they performed the procedure on C6 deficient rats, and saw no difference in pain sensitivity compared to normal rats. Since C6 is required for the formation of the MAC, these data suggest that MAC formation does not play a role in pain, at least in this model.

A different C5aR antagonist, PMX53 [42] was used by Ting and coworkers [43] to examine the role of C5a in inflammatory hypernociception. In the Randall-Selitto test (the paw pressure test) [44], rats were injected in the hindpaw with known complement activators, zymosan; carrageenan, or lipopolysaccharide. Then nociception was measured after pressure was applied using an electronic pressure meter. They found that injection of PMX53, either before or after injection of zymosan, reduced hypernociception. PMX53 injection also lowered hypernociception caused by ovalbumin injection into the hind paw. They noted that PMX53 injection inhibited neutrophil migration caused by zymosan, but not that caused by carrageen or LPS. Treatment of the rats with the immunosuppressant anticancer microtubule disruptor vinblastine before injection of C5a, zymosan, or carrageen both blocked neutrophil migration and reduced hypernociception. Finally, they noted that treatment with PMX53 did not affect the levels of TNF-α or IL-1β. From this, they concluded that the role of C5a in inflammatory hypernociception does not involve the production of hypernociceptive cytokines, but does require the presence of neutrophils.

Complement fragments C5a and C3a were injected into the rat hindpaw to evaluate their role in pain [45]. Intraplantar injection of C5a or C3a elicited heat hyperalgesia, and sensitized C-nociceptors as evidenced by an increase in the proportion of heat-sensitive fibers. A-nociceptors were also activated by complement. Interestingly, in the absence of incision or inflammatory stimulus, the complement fragments sensitized responses to heat, but not to mechanical stimulation. The same group reports finding C5a receptor mRNA in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG), and found that both C5a and C3a facilitated capsaicin-induced intracellular calcium mobilization in DRG neurons. These findings add to the evidence that the complement system activated and sensitizes cutaneous nociceptors. In 2011, Jang et al. [46] extended this research using incisional edema to model post-surgical pain. They measured C5a receptor (C5aR) mRNA in the skin, DRG, and spinal cord, and C5a protein levels in the skin surrounding the incision. They found that the C5aR mRNA and protein were increased in the DRG and wound site for at least 72 hours following the incision. This evidence supports their conclusion that high local concentrations of C5a produced in wounds contribute to postoperative pain. In this report, Jang and coworkers also used the C5aR antagonist PMX53 to study the role of C5a in incisional pain. They noted that mice treated with PMX53 had less heat hyperalgesia between 2 and 72 hours after the incision, while the PMX treated mice only had reduced mechanical allodynia between 48 and 72 hours. Intraplantar injection of C5a also caused increased heat hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia, which was reduced by injection of PMX53 30 minutes prior to the C5a injection. They found that, following incision, C5, C5aR, and C5aR mRNA showed a dramatic increase, though no increases in protein or mRNA levels were seen in either the DRG or the spinal cord. Little stimulation by C5a was seen in vitro in skin nerve fibers, and no effect of PMX53 was seen. The authors explanation was that indirect, e.g. the C5a-directed release of other factors that may be more directly responsible for the nociceptive pain seen in this study. Finally they observed that both C3a and C5a facilitated capsaicin dependent changes in Ca+2 concentration.

Sorkin and coworkers [47] described two monoclonal antibodies against the GD2 ganglioside, where one (ch14.18) was able to fix complement, and the second (hu14.18K322A), with a single point mutation, was not. Comparing the activities of these antibodies, they noted that Ch14.18 induced allodynia, while hu14.18K322A did so to a far lesser extent. In addition, they found that the mechanical allodynia induced by hu14.18K322A was much shorter-lived than that induced by ch14.18. They demonstrated that C5a production is important in their model by pretreating rats with the C5aR antagonist AcF-[OPdChaWR]. The pre-treated rats showed no response to injection with ch14.18, while control rats showed a significant lowering of the pain threshold. It is interesting that when they repeated the above experiment on rats that didn’t express C6, a vital component of the MAC, the C6− rats also showed no pain response to the injection of ch14.18, implying that the MAC plays a central role in complement mediated pain in this model. This is in contrast to the results obtained by Griffin, (2007) [38] who showed that C6-deficient rats had the same sensitivity to pain in their model. The authors explained this difference by noting that, in their model, maximum allodynia was seen 30 to 45 minutes, while Griffin and coworkers did their measurements after three days. In addition, they cited differences in their experimental protocols.

C5aR−/− (C5aR knockout mice) mice were used to examine the role C5a in incisional pain by Liang and coworkers [37]. They found that the mice without C5a receptors showed less heat hyperalgesia than normal mice, and that the C5aR null mice also showed less mechanical allodynia, though only after 48 hours post-incision. C5aR null mice had much less edema than normal mice following the incision, with the small amount of edema seen disappearing after 24 hours. C5aR null mice also showed no increase in IL-1β and NGF after incision, while increases were seen in normal mice. It has been shown these factors are important in nociceptive pain modulation after incisional injury [48]. They concluded that C5a plays an important role in both heat hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia, as well as in stimulating the migration of neutrophils into the epidermis and muscle around the wound.

In a recent paper, Shutov and co-workers [49] were able to partially establish the connection between C5a production and neuropathic pain. Repeating experiments with C5aR−/− mice and mice treated with PMX53 (see above), they found that both heat and mechanical related hyperalgesia were reduced in C5aR knockout mice, and by wild type mice treated with the C5aR inhibitor PMX53. Then they found that the heat related hyperalgesia caused by C5a injection into mouse hind paws was significantly reduced in TRPV1 (transient receptor potentialcation channels vanilloid) knockout mice, and in mice treated with the TRPV1 antagonist AMG9810. TRPV1 has been implicated in nociceptive pain [50]. They were able to show that in skin, C5aR was found almost entirely in macrophages. Using mice with a macrophage suicide gene, they were able to show that reducing the number of macrophages was able to significantly reduce nociceptive pain, and completely abolished C5a mediated heat hyperalgesia. Next, they studied the levels of cytokines in tissue injected with C5a. Since the NGF production profile matched the profile of increased heat related hyperalgesia, and because NGF is known to increase the expression of TRPV1 channels [51], the authors decided to study the connection between NGF production and heat related hyperalgesia. Using an anti-NGF antibody, they found that injection of the antibody reduced thermal hyperalgesia caused both by C5a and NGF, thus establishing the role of NGF in C5a induced thermal hyperalgesia.

In a slightly different study, Moriconi and coworkers [52] used rational drug design to make a small molecule C5aR inhibitor, DF2593A. While DF2593A does not prevent C5a binding to C5aR, it appears to restrict small conformational changes in C5aR that are necessary for its activity. It proved to be effective in reducing both thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia. DF2593A also proved effective in models of chronic inflammatory pain and inflammatory arthritic disease, but not in models of pain caused by epinephrine and PGE2, which are directly involved in the activation of nociceptive neurons.

JOINT INFLAMATION AND RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS PAIN

It is clear that the anaphylatoxin C5a is a potent inducer of inflammatory edema by a neutrophil-dependent mechanism. Strikingly high numbers of neutrophils are present in the synovial fluid during the acute inflammatory phase of rheumatoid arthritis. A radioimmunoassay was used to measure C5a levels in the synovial fluid from the joints of 22 rheumatoid arthritis patients [53]. It was found that C5a was present in a concentration of 2.5 nM, sufficient to induce neutrophil accumulation and microvascular plasma protein leakage. C5a (20 ng/ml) and C3a (4 ug/ml) were present in the synovial fluid at levels four-fold greater in rheumatoid arthritis patients, as compared to controls, but beneath the level of quantitation in the plasma from the same patients. These findings demonstrate that C3a and C5a may be important in joint swelling and pain in rheumatic joints.

COMPLEMENT DEPLETION TO AMELIORATE PAIN

The studies listed above strongly suggest that local overproduction of complement anaphylatoxins (C3a and C5a) may be responsible for a substantial amount of the pain that occurs in the above mentioned conditions. There is also a substantial body of literature that shows that in animal models of pain, complement depletion by cobra venom factor is able to greatly lessen the pain felt by the subject. For example, Levin et al. (2008) [26] demonstrated that complement depletion by CVF significantly attenuated pain in spinal nerve ligation rats, a rat model for chronic pain. In another study [30], it was shown that complement depletion by CVF essentially prevented the occurrence of hyperalgesia caused by peripheral nerve injury when injected 10 minutes prior to the surgery (and injected daily thereafter), and nearly reversed the hyperalgesia when injected four days after the surgery (Fig. 2).These studies show the potential of complement depletion as a treatment for pain.

CONCLUSION

The articles referenced in this review clearly show that complement activation is required for neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Complement activation results in the production of the anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a, which are directly involved in neuropathic pain. C5a, being the stronger anaphylatoxin, appears to be the direct link between complement activation and pain. Neuropathic and inflammatory pain are mainly caused by binding of C5a to its receptor, C5aR, which causes the release of cytokines that attract macrophages and neutrophils. Recent work has shown that the activation of TRPV1 ion channels by NGF plays an important role in neuropathic and inflammatory pain.

This elucidation of the complement-related pain pathways also reveals a number of potential drug targets that may be useful to ameliorate neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Two drugs that prevent the binding of C5a to its receptor (PMX53 and AcF-[POdChaWR]) showed promise in reducing pain in animal models. However, due to bioavailability and stability problems, these promising molecules have not made it into the clinic. Another group used rational drug design to design a small molecule that binds noncompetitively to C5aR, DF2593A. While this drug does not prevent C5a binding, it does stop C5aR from activating the pain pathways. Finally, the work of Nie and coworkers described here shows that complement depletion with CVF may prove to be another method for reducing complement mediated neuropathic and inflammatory pain.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Declared none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torrance N, Ferguson JA, Afolabi E, et al. Neuropathic pain in the community: more under-treated than refractory? Pain. 2013;154(5):690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.022. [PMID: 23485369] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0. [PMID: 25575710] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujita T. Evolution of the lectin-complement pathway and its role in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(5):346–353. doi: 10.1038/nri800. [PMID: 12033740] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gros P, Milder FJ, Janssen BJ. Complement driven by conformational changes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(1):48–58. doi: 10.1038/nri2231. [PMID: 18064050] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rother K, Till GO, Hänsch GM. The complement system. 2nd. Berlin, New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller-Eberhard HJ. Molecular organization and function of the complement system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:321–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001541. [PMID: 3052276] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walport MJ. Complement. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(14):1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. [PMID: 11287977] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walport MJ. Complement. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(15):1140–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441506. [PMID: 11297706] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter RR, Reid KBM. Advances in Protein Chemistry. Netherland: Elsevier. 1979:1–71. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60458-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji X, Azumi K, Sasaki M, Nonaka M. Ancient origin of the complement lectin pathway revealed by molecular cloning of mannan binding protein-associated serine protease from a urochordate, the Japanese ascidian, Halocynthia roretzi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(12):6340–6345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6340. [PMID: 9177219] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pangburn MK, Müller-Eberhard HJ. Initiation of the alternative complement pathway due to spontaneous hydrolysis of the thioester of C3. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. (3rd) 1983;421:291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb18116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merle NS, Church SE, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Roumenina LT. Complement system part I - molecular mechanisms of activation and regulation. Front Immunol. 2015;6:262. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00262. [PMID: 26082779] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nonaka M, Kimura A. Genomic view of the evolution of the complement system. Immunogenetics. 2006;58(9):701–713. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0142-1. [PMID: 16896831] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller DJ, Hemmrich G, Ball EE, et al. The innate immune repertoire in cnidaria-ancestral complexity and stochastic gene loss. Genome Biol. 2007;8(4):R59. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r59. [PMID: 17437634] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Y, Thangamani S, Ho B, Ding JL. The ancient origin of the complement system. EMBO J. 2005;24(2):382–394. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600533. [PMID: 15616573] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naish PF, Aber GM, Boyd WN. C3 deposition in renal arterioles in the loin pain and haematuria syndrome. BMJ. 1975;3(5986):5746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5986.746. [PMID: 1174876] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds DN, Smith SA, Zhang YP, et al. Vaccinia virus complement control protein reduces inflammation and improves spinal cord integrity following spinal cord injury. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1035:165–178. doi: 10.1196/annals.1332.011. [PMID: 15681807] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotwal GJ, Isaacs SN, McKenzie R, Frank MM, Moss B. Inhibition of the complement cascade by the major secretory protein of vaccinia virus. Science. 1990;250(4982):827–830. doi: 10.1126/science.2237434. [PMID: 2237434] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J-M, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;45(2):27–37. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e. [PMID: 17426506] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dailey AT, Avellino AM, Benthem L, Silver J, Kliot M. Complement depletion reduces macrophage infiltration and activation during Wallerian degeneration and axonal regeneration. J Neurosci. 1998;18(17):6713–6722. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06713.1998. [PMID: 9712643] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogel C-W, Smith CA, Müller-Eberhard HJ. Cobra venom factor: structural homology with the third component of human complement. J Immunol. 1984;133(6):3235–3241. [PMID: 6491285] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochrane CG, Müller-Eberhard HJ, Aikin BS. Depletion of plasma complement in vivo by a protein of cobra venom: its effect on various immunologic reactions. J Immunol. 1970;105(1):55–69. [PMID: 4246566] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twining CM, Sloane EM, Schoeniger DK, et al. Activation of the spinal cord complement cascade might contribute to mechanical allodynia induced by three animal models of spinal sensitization. J Pain. 2005;6(3):174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.11.011. [PMID: 15772911] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mold C, Tamerius JD, Phillips G., Jr Complement activation during painful crisis in sickle cell anemia. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;76(3 Pt 1):314–320. doi: 10.1006/clin.1995.1131. [PMID: 7554454] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Peake PW, Charlesworth JA, Tracey DJ, Moalem-Taylor G. Complement activation contributes to leukocyte recruitment and neuropathic pain following peripheral nerve injury in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26(12):3486–3500. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05971.x. [PMID: 18052971] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin ME, Jin JG, Ji R-R, et al. Complement activation in the peripheral nervous system following the spinal nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2008;137(1):182–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.11.005. [PMID: 18160218] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jinsmaa Y, Takahashi M, Takahashi M, Yoshikawa M. Anti-analgesic and anti-amnesic effect of complement C3a. Life Sci. 2000;67(17):2137–2143. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00800-6. [PMID: 11057763] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jinsmaa Y, Takenaka Y, Yoshikawa M. Designing of an orally active complement C3a agonist peptide with anti-analgesic and anti-amnesic activity. Peptides. 2001;22(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00352-1. [PMID: 11179594] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pohorecky LA, Skiandos A, Zhang X, Rice KC, Benjamin D. Effect of chronic social stress on delta-opioid receptor function in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290(1):196–206. [PMID: 10381776] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nie F, Wang J, Su D, et al. Abnormal activation of complement C3 in the spinal dorsal horn is closely associated with progression of neuropathic pain. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31(6):1333–1342. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1344. [PMID: 23588254] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Till GO, Morganroth ML, Kunkel R, Ward PA. Activation of C5 by cobra venom factor is required in neutrophil-mediated lung injury in the rat. Am J Pathol. 1987;129(1):44–53. [PMID: 3661679] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quadros AU, Cunha TM. C5a and pain development: An old molecule, a new target. Pharmacol Res. 2016;S1043–S6618(16):00041–00044. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.004. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1043661816000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine JD, Gooding J, Donatoni P, Borden L, Goetzl EJ. The role of the polymorphonuclear leukocyte in hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 1985;5(11):3025–3029. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-11-03025.1985. [PMID: 2997412] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wahba AV, Barnes B, Lazarus GS. Labeling of peripheral blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes with indium-111: a new method for the quantitation of in-vivo accumulation of PMNLs in rabbit skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;82(2):126–131. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12259669. [PMID: 6420476] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark JD, Qiao Y, Li X, Shi X, Angst MS, Yeomans DC. Blockade of the complement C5a receptor reduces incisional allodynia, edema, and cytokine expression. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(6):1274–1282. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00024. [PMID: 16732100] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strachan AJ, Woodruff TM, Haaima G, Fairlie DP, Taylor SM. A new small molecule C5a receptor antagonist inhibits the reverse-passive Arthus reaction and endotoxic shock in rats. J Immunol. 2000;164(12):6560–6565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6560. [PMID: 10843715] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang D-Y, Li X, Shi X, et al. The complement component C5a receptor mediates pain and inflammation in a postsurgical pain model. Pain. 2012;153(2):366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.032. [PMID: 22137294] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffin RS, Costigan M, Brenner GJ, et al. Complement induction in spinal cord microglia results in anaphylatoxin C5a-Mediated pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8699–8708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2018-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Decosterd I, Woolf CJ. Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2000;87(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00276-1. [PMID: 10924808] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33(1):87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [PMID: 2837713] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50(3):355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [PMID: 1333581] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woodruff TM, Crane JW, Proctor LM, et al. Therapeutic activity of C5a receptor antagonists in a rat model of neurodegeneration. FASEB J. 2006;20(9):1407–1417. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5814com. [PMID: 16816116] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ting E, Guerrero AT, Cunha TM, et al. Role of complement C5a in mechanical inflammatory hypernociception: potential use of C5a receptor antagonists to control inflammatory pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(5):1043–1053. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707640. [PMID: 18084313] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos-Nogueira E, Redondo Castro E, Mancuso R, Navarro X. Randall-Selitto test: a new approach for the detection of neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(5):898–904. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1700. [PMID: 21682605] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jang JH, Clark JD, Li X, Yorek MS, Usachev YM, Brennan TJ. Nociceptive sensitization by complement C5a and C3a in mouse. Pain. 2010;148(2):343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.11.021. [PMID: 20031321] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jang JH, Liang D, Kido K, et al. Increased local concentration of complement C5a contributes to incisional pain in mice. J Neuroinflammation BioMed Central Ltd; 2011;8:80. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorkin LS, Otto M, Baldwin WM, III, et al. Anti-GD(2) with an FC point mutation reduces complement fixation and decreases antibodyinduced allodynia. Pain. 2010;149(1):135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.01.024. [PMID: 20171010] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woolf CJ, Allchorne A, Safieh-Garabedian B, Poole S. Cytokines, nerve growth factor and inflammatory hyperalgesia: the contribution of tumour necrosis factor α. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121(3):417–424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701148. [PMID: 9179382] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shutov LP, Warwick CA, Shi X, et al. The complement system component C5a produces thermal hyperalgesia via Macrophage-to-Nociceptor signaling that requires NGF and TRPV1. J Neurosci. 2016;36(18):5055–5070. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3249-15.2016. [PMID: 27147658] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Immke DC, Gavva NR. The TRPV1 receptor and nociception. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17(5):582–591. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.09.004. [PMID: 17196854] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X, Huang J, McNaughton PA. NGF rapidly increases membrane expression of TRPV1 heat-gated ion channels. EMBO J. 2005;24(24):4211–4223. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600893. [PMID: 16319926] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moriconi A, Cunha TM, Souza GR, et al. Targeting the minor pocket of C5aR for the rational design of an oral allosteric inhibitor for inflammatory and neuropathic pain relief. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(47):16937–16942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417365111. [PMID: 25385614] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jose PJ, Moss IK, Maini RN, Williams TJ. Measurement of the chemotactic complement fragment C5a in rheumatoid synovial fluids by radioimmunoassay: role of C5a in the acute inflammatory phase. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. BMJ Group. 1990;49:747–752. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.10.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]