Abstract

This study prospectively examines the transition from the child welfare system into the juvenile justice system among 10,850 maltreated children and adolescents and explores how patterns of risks, including severity and chronicity of maltreatment, adverse family environment, and social risk factors, affect service systems transition. Almost three percent of maltreated children and adolescents had their first juvenile justice adjudication within an average of approximately six years of their initial child protective services investigation (CPS). Social risk factors, including a child’s age at index CPS investigation (older), gender (boys), and race/ethnicity (Black and Hispanic vs. White) significantly predicted the risk of transition into the juvenile justice system. Recurrence of maltreatment and experiencing at least one incident of neglect over the course of the study period also increased the risk of transition into the juvenile justice system. However, subtypes of maltreatment, including physical, sexual, and other types of abuse did not significantly predict the risk of juvenile justice system transition. Finally, family environment characterized by poverty also significantly increased the risk of juvenile justice system transition. These findings have important implications for developing and tailoring services for maltreated children, particularly those at-risk for transitioning into the juvenile justice system.

Keywords: maltreatment, child welfare, delinquency, juvenile justice, family environment, crossover youth

It is estimated that approximately 30% of children under the care of the child welfare system (CWS) are subsequently involved in the juvenile justice system (JJS) due to involvement in delinquent behaviors (Smith, Ireland, & Thornberry, 2005). More commonly referred to as crossover youth (Herz et al., 2012), these children and adolescents are a high risk and vulnerable population with complex needs, likely because of their experience of multiple adversities and trauma (Baglivio et al., 2015; Herz, Ryan, & Bilchik, 2010). For example, maltreatment, including neglect, and physical, sexual, and other types of abuse, is among the most common risk factors associated with service systems crossover (Herz et al., 2012; Mersky, Topitzes, & Reynolds, 2012). Despite the strong evidence demonstrating the link between maltreatment and delinquency, however, many children and adolescents who experience maltreatment do not engage in delinquent behaviors nor do they transition into the JJS (Widom, 1989a, 1989b). Thus, it is critical to examine what factors might differentiate maltreated children and adolescents who transition into the JJS from those who do not, in order to inform service delivery and prevent deeper involvement in service systems.

Childhood adversities such as maltreatment do not happen in isolation. A challenging family environment, for example, is associated with negative developmental outcomes such as maltreatment (Dodge, Greenberg, & Malone, 2008; Beyers, Bates, Pettit, & Dodge, 2003). An adverse family environment may also impact the likelihood of involvement in delinquent behaviors among maltreated children and adolescents (Najman et al., 2010), and may contribute to transition into the JJS. Evidence also suggests that transition from the CWS into the JJS is characterized by disparities based on social risk factors. Boys and racial/ethnic minority youth are disproportionately represented in the crossover youth population (Herz et al., 2012). In this study, we prospectively tracked a cohort of maltreated children and adolescents referred to child protective services and then identified patterns of risks between those who transitioned from the CWS into the JJS compared to those who did not. Understanding how patterns of risks contribute to service systems transition is critical to intervention development and resource allocation for high risk and vulnerable children and adolescents.

The Link between Maltreatment and the Child Welfare-Juvenile Justice (CWS-JJS) Transition

There is strong empirical evidence demonstrating the association between maltreatment and delinquency (Postlethwait, Barth, & Guo, 2010; Ryan & Testa, 2005; Stouthamer-Loeber, Wei, Homish, & Loeber, 2002). This evidence supports the assumption that maltreated children and adolescents are likely to engage in more delinquent behaviors, and also, transition from the CWS into the JJS. For example, in a longitudinal study of 884 urban youth, Smith and colleagues (2005) examined the impact of maltreatment during adolescence on young adult offending. Their findings indicate that about 35% of youth had substantiated cases of maltreatment prior the age of 12 and approximately 9% of youth experienced maltreatment between the ages of 12 and 17. Compared to non-maltreated youth, maltreated youth had higher rates of arrests for general, violent, and substance abuse offenses during late adolescence and early adulthood.

The cycle of violence theory (Widom, 1989a, 1989b) provides some insight into explaining the link between maltreatment and delinquency. Consistent with a social learning perspective (Bandura, 1973), this theory posits that maltreatment increases the likelihood of involvement in crime and delinquency through modeling of aggressive behavior. For example, matched comparison studies between maltreated and non-maltreated children have shown that physical abuse compared to other types of abuse had the greatest impact on delinquent behaviors (Dodge, Bates, Pettit, 1990; Widom, 1989a), and maltreatment perpetrated by parents is believed to have more severe health repercussions than incidents committed by other family or nonfamily members (DiLillo et al., 2010). In line with the commonly held belief that violence begets violence, the cycle of violence theory suggests that maltreatment may exacerbate the risk for subsequent involvement in delinquent or violent behaviors (Widom, 1989b).

An alternative perspective based on cumulative risk theory posits that the accumulation of risks over time significantly contributes to poor developmental outcomes (Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen, & Sroufe, 2005; Bauman, Silver, & Stein, 2006; Sameroff, Seifer, Zax, & Barocos, 1987). For example, early and chronic exposure to adverse events may place children at greater risk for poor behavior outcomes in adolescence (Appleyard et al., 2005). In one study, Ryan and Testa (2005) compared the delinquency rates between maltreated and non-maltreated children, and examined whether factors such as recurrence of maltreatment is associated with involvement in delinquent behaviors. Their findings showed that children who experienced two to three substantiated reports of maltreatment had a greater likelihood of involvement in delinquency. Chronicity of maltreatment may expose a child to new risk factors and exacerbate the progression of risk within and across development due to the child’s removal from home or having to experience multiple residential transitions (Connell, Vanderploeg, Katz, Caron, Saunders, & Tebes, 2009; Leve et al., 2012). Thus, children who experience frequent maltreatment and are exposed to more risk factors for long periods of time are at greater likelihood for externalizing behaviors, including involvement in delinquent behavior (Cicchetti, 2013; Dodge et al., 2008; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 2002). Yet, it is not clear how severity and chronicity of maltreatment differentially influence children’s prolonged involvement in and transitions across service systems.

Family Environment as a Risk Factor in Child Welfare-Juvenile Justice Transition

Research suggests that children and youth who experience service systems transitions are more likely to come from disadvantaged family backgrounds that have less stable family relationships and lower social support compared to single system-involved youth (Herz et al., 2010; Ryan, Williams, & Courtney, 2013). For instance, two-thirds of youth who experienced a CWS-JJS transition were in an out-of-home placement when they were arrested (Huang, Ryan, & Herz, 2012), two-thirds had a history of running away (Dale, Baker, Anastasio, & Purcell, 2007), and up to one-third had parents with drug and alcohol problems (Ryan et al., 2013). These risk factors do not happen in isolation and are typically compounded by other challenges, including poverty and domestic violence.

Exposure to poverty in early childhood plays a critical role in shaping developmental outcomes during adolescence (Aneshensel, 2009; Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998). For example, persistent exposure to poverty during childhood is linked to increased involvement in delinquency (Jarjoura, Triplett, & Brinker, 2002). Strikingly, financial difficulties and receipt of public assistance are associated with a 325% increase in risk of re-referral to child protective services among children with previous CWS involvement (Connell, Bergeron, Katz, Saunders, & Tebes, 2007). Accounts of domestic violence in the home are also associated with elevated risk for internalizing as well as externalizing behaviors such as delinquency (Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, 2008; Moylan et al., 2010) and recurrent child maltreatment (DePanfilis & Zuravin, 1999). Taken together, there is strong research evidence to suggest that adverse family environment may differentially place a child at greater risk for a CWS-JJS transition.

Social Risk Factors and Disparities in the Child Welfare-Juvenile Justice Transition

Social risk factors, including racial/ethnic minority status, age, and gender significantly predict the likelihood of crossover status. For example, Black children are more likely to be subsequently or concurrently involved in CWS and JJS than White children and other minority groups (Graves, Frabutt, Shelton, 2007; Huang et al., 2012; Jonson-Reid & Barth, 2000). These findings are also consistent with research on disproportionate minority contact across different service systems, particularly the JJS, such that Black youth are more likely to be recommended for formal processing, prosecuted for felony crimes, and found delinquent, compared to White youth, even when prior records are considered (Bishop, Leiber, & Johnson, 2010; Peck & Jennings, 2016).

Transition from the CWS to JJS also usually takes place as the child ages and undergoes developmental changes. For example, a confluence of developmental changes, including impulsivity, susceptibility to peer pressure and influence, and transient nature and personality, including greater expectations for autonomy, contribute to increased risk-taking behaviors in adolescence (Steinberg, 2008). The interaction between these developmental changes and the accumulation of risk across development places a child with previous CWS involvement at risk for continued and deeper involvement with multiple systems such the JJS. Further, older children compared to younger children may be held more accountable for problem behaviors, particularly law-breaking behaviors, which may require the involvement of the JJS (Woolard & Scott, 2009; Scott & Steinberg, 2008), and thus, result in a greater likelihood in crossing over from the CWS to the JJS.

Findings on the relationship of gender to the CWS-JJS transition generally suggest that boys compared to girls are more likely to transition from the CWS into the JJS (Ryan et al., 2013; Graves et al., 2007). These findings can be attributed to gender differences in the effects of maltreatment and chronicity of delinquent behaviors. Studies have shown that the effects of maltreatment vary by gender such that boys are more likely to develop externalizing problems and girls are more likely to develop internalizing symptoms in response to maltreatment (Topitzes, Mersky, & Reynolds, 2011). In relation, the link between childhood maltreatment and delinquent behaviors appears stronger in boys than girls. Sexual abuse was predictive of violent offending for boys but not for girls (Asscher, Van der Put, & Stams, 2015). Research also suggests that boys engaged in more chronic problem behaviors than girls resulting to increased likelihood of involvement in the JJS (Miller et al., 2010).

Importantly, most of the studies examining CWS-JJS transitions have utilized retrospective designs (Baglivio et al., 2015; Haight, Bidwell, Choi, & Cho, 2016; Ryan et al., 2013), which do not capture the critical period when a child first transitions from the CWS and becomes involved in the JJS. Literature has shown that the onset age of offending is among the strongest predictors of long-term and continuous delinquent behavior (Gann et al., 2015). Understanding prospective patterns in systems transitions among maltreated children, particularly during initial contact with the JJS, may identify critical periods for intervention and prevent prolonged multisystem involvement.

The Current Study

The current study extends the existing literature by prospectively tracking a cohort of maltreated children and adolescents referred to child protective services (CPS), while also taking into account the impact of cumulative individual, family, and social risk factors. Based on the cycle of violence and cumulative risk theories, we hypothesized that increased exposure to adverse experiences, including chronic and severe maltreatment, prior victimization, parental substance use, domestic violence, and poverty, would significantly increase the risk of transition into the JJS among maltreated children and adolescents. Consistent with research on disproportionate minority contact, we also hypothesized that maltreated racial and ethnic minority children and adolescents would be at greater risk of transition into the JJS than maltreated White children and adolescents. Boys compared to girls would also be at greater risk of transition into the JJS. Finally, we expected that as children grow older, the risk of transition into the JJS would increase.

Method

Data sources and preparation

This study was conducted using CPS data submitted by the Rhode Island Department of Children Youth and Families (DCYF) to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS). The NCANDS is the official data system of the Children’s Bureau of the US Department of Health and Human Services and was created in response to the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1988. Each year, states voluntarily submit case and aggregate level data on child abuse and neglect to the NCANDS. Data used in this study comprised a subsample of Rhode Island DCYF submissions of all completed CPS investigations from 2000–2007 (described in greater detail in the Sample section below).

Prior to analyses, the NCANDS data were aggregated to collapse information across the eight-year period (2000–2007). Variables include child demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity), CPS case characteristics (e.g., prior victimization history, maltreatment type), case disposition, and family characteristics (e.g., parental substance use, exposure to domestic violence, receipt of public assistance). There were a total of 88,269 reports of substantiated and unsubstantiated maltreatment in 2000–2007, involving 51,044 children and youth ages 0–18 years. Previous research suggests that minimal differences exist, including in risk of remaltreatment, between substantiated and unsubstantiated cases (Drake, Jonson-Reid, Way, & Chung, 2003; also see Connell et al., 2007); thus, we included both substantiated and unsubstantiated cases of maltreatment in our final sample as described below.

In addition to data from the NCANDS, supplemental data from the Rhode Island juvenile correctional services for the period from 2007 to 2012 were also utilized in this study. Data include adjudicated delinquency cases that received probation or incarceration as disposition. These data comprised a total of 6,784 adjudicated cases involving 3,431 children and youth. Variables include child demographic characteristics, offense type (person, property, drugs, misdemeanor offenses), disposition (probation or incarceration), and date of disposition. These data were linked to the NCANDS to identify children with juvenile justice involvement subsequent to their index CPS maltreatment incident. CPS and JJS cases were matched using a unique child identification number.

Coding Child, Family, and Juvenile Justice Variables

Child Demographics

Age was calculated by subtracting the index maltreatment incident date from the child’s date of birth. Gender was coded as 0=female and 1=male. Race and ethnicity were categorized as 0=White, 1=Black, 2=Hispanic, and 3=other.

CPS Case Characteristics

Prior victimization, recurrence of maltreatment, subtypes of maltreatment, and counts of maltreatment subtypes described the child’s CPS case characteristics. Prior victimization indicates whether a child had a history of victimization prior their initial CPS involvement (0=no, 1=yes). Recurrence of maltreatment indicates whether a child experienced subsequent CPS investigation for maltreatment (0=no, 1=yes). Maltreatment subtype describes whether a child experienced at least one incident of physical, neglect, sexual, or other type of abuse (0=none, 1=1 or more). Counts of maltreatment subtypes indicate the number of different subtypes of maltreatment experienced by a child over the course of the study period (range= 1 to 4).

Family Characteristics

Parental substance use indicates whether there was a history of substance use by a parent during the course of the study period (0=no, 1=yes). Domestic violence indicates whether the child was exposed to domestic violence at any time during the course of the study period (0=no, 1=yes). Finally, public assistance indicates whether the child and his/her family received public assistance at any time during the course of the study period (0=no, 1=yes).

Juvenile Justice Variables

Age at JJS involvement, offense type, and case disposition were utilized to provide descriptive information regarding maltreated children who were subsequently involved in the JJS. Age was calculated by subtracting the case adjudication date from the child’s date of birth. Offense type includes person, property, drugs, other felony, and misdemeanor offenses. Finally, case disposition describes whether the child was placed on probation (community supervision) or in a secure juvenile confinement facility (e.g., training school).

Sample

For the purposes of this study, we selected a cohort of children from the NCANDS born in 1994, 1995, 1996, or 1997. Recall that one of our aims was to examine factors associated with CWS-JJS transition. In particular, we were interested in a child’s initial involvement in the JJS. In 11 states, the lower age boundary for juvenile justice involvement is 10, and in 33 states (including Rhode Island), the lower age boundary is not specified and a child may be brought to the juvenile justice system depending on the crime committed or the discretion of juvenile justice actors (Juvenile Justice Geography, Policy, Practice, & Statistics (JJGPS)). Children in our selected cohort were ages 10–13 in 2007 (JJS records were available for the period from 2007 to 2012), which generally reflect the age of a child’s initial juvenile justice involvement (JJGPS). Our final sample included 10,850 children with maltreatment incidents reported for the period from 2000 to 2007. A majority of the children were boys (54%) with an average age of 6.7 (SD = 2.6; range 2–13) at the time of index event. Forty seven percent identified their racial and ethnic background as White, 11% Black, 17% Hispanic, 4% other, and 21% did not have racial or ethnic information. In terms of case history, 18% of children in our sample had prior victimization and more than one-third (35%) experienced remaltreatment. Neglect was the most frequent subtype of maltreatment—80% of children and adolescents experienced neglect over the eight-year study period. Almost 25% of children experienced more than one type of maltreatment. With regard to family characteristics, one out of five children in our sample had been exposed to domestic violence, 24% had parents who use illegal substance, and 46% received public assistance. Table 1 presents a summary of descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Total Sample of Maltreated Children

| M (SD) % |

|

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age at index CPS referral (years) | 6.71 (2.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 54 |

| Female | 46 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 60 |

| Black | 14 |

| Hispanic | 21 |

| Other | 5 |

| Case Characteristics | |

| Prior Victimization | 18 |

| Remaltreatment | 35 |

| Maltreatment Subtypea | |

| Physical | 33 |

| Neglect | 80 |

| Sexual | 9 |

| Other | 6 |

| Maltreatment Subtype Count | |

| One | 76 |

| Two | 21 |

| Three | 3 |

| Four | .4 |

| Family Characteristics | |

| Parental Substance Use | 24 |

| Exposure to Domestic Violence | 20 |

| Receipt of Public Assistance | 46 |

Experienced at least one incident throughout the duration of the study period (2000–2007)

Analysis Plan

First, we described the prevalence of CWS- JJS transition and the justice system characteristics of children and adolescents who transitioned into the JJS. Next, we conducted chi-square and t-tests to describe the child, family, and case characteristics of maltreated children and examine whether these characteristics vary by crossover status. Finally, we conducted survival analysis using Cox regression to examine the risk of CWS-JJS transition following initial maltreatment referral to CPS. The Cox regression is a frequently used technique for analysis of timing of event occurrence (e.g., CWS-JJS transition) and models event rates in the presence of censored data, or cases for whom the outcome is not observed by the conclusion of the study observation period (Connell, 2012; Allison, 1995). The model follows a regression framework and employs a log-linear model to determine the extent to which a set of covariates influences the dependent variable, survival time. Children and adolescents who did not experience the outcome of interest (i.e., CWS-CWS-JJS transition) were censored at the end of the study observation period. All analyses were conducted in SPSS 21.

Results

Prevalence of CWS-CWS-JJS transition (Crossover Status)

In our final sample of 10,850 maltreated children, 2.5% (n = 275) had subsequent JJS involvement within an average of 76.3 months (6.4 years) following their initial CPS referral for maltreatment. On average, these children and adolescents (referred to as crossover group) were 14.2 years old (SD = 1.2, range = 12 to 17) during their first delinquency adjudication. Thirty seven percent were charged with a person offense, 35% with a property offense, 10% with drug-related and other felony offense, and 18% with misdemeanor. A majority (85%) of these children received probation as court disposition and the remaining 15% were placed in a secure juvenile facility.

Child, Case, and Family Characteristics by Crossover Status

Child Demographics

Child demographic characteristics significantly vary by crossover status as shown in Table 2. There were more boys in the crossover group (75%) than those who did not transition into the JJS (53%, referred to as CWS-only), X2 (1, N = 10,822) = 52.7, p = .000. Race and ethnicity also vary by crossover status. There was a greater proportion of Black (29% vs. 14%) and fewer White (45% vs. 60%) children in the crossover group than in the CWS-only group. X2 (3, N = 8,546) = 44.6, p = .000. Children in the crossover group were older (M = 7.8, SD = 2.3) during their reported index maltreatment incident compared to the CWS-only group (M = 6.7, SD = 2.6), t(10848) = −7.2, p = .000.

Table 2.

Child, Case, and Family Characteristics by Crossover Status

| CWS-only M (SD) % |

Crossover M (SD) % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Child Characteristics | ||

| Age at index CPS referral (years)*** | 7.81 (2.26) | 6.68 (2.59) |

| Gender* | ||

| Male | 53 | 75 |

| Female | 47 | 25 |

| Race/Ethnicity*** | ||

| White | 60 | 45 |

| Black | 14 | 29 |

| Hispanic | 21 | 22 |

| Other | 5 | 5 |

| Case Characteristics | ||

| Prior Victimization*** | ||

| No | 82 | 70 |

| Yes | 18 | 30 |

| Remaltreatment*** | ||

| No | 66 | 37 |

| Yes | 34 | 63 |

| Maltreatment Subtypea | ||

| Physical* | 33 | 39 |

| Neglect*** | 79 | 90 |

| Sexual | 9 | 9 |

| Other | 6 | 6 |

| Maltreatment Subtype Count*** | ||

| One | 76 | 62 |

| Two | 21 | 31 |

| Three | 3 | 6 |

| Four | .4 | 1 |

| Family Characteristics | ||

| Parental Substance Use*** | ||

| No | 76 | 59 |

| Yes | 24 | 41 |

| Exposure to Domestic Violence** | ||

| No | 80 | 72 |

| Yes | 20 | 28 |

| Receipt of Public Assistance*** | ||

| No | 55 | 22 |

| Yes | 45 | 78 |

Experienced at least one incident throughout the duration of the study period (2000–2007)

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Case Characteristics

Case characteristics also vary by crossover status. Also shown in Table 2, a greater proportion of children in the crossover group experienced prior victimization (30% vs. 18%), X2 (1, N = 10,850) = 30.1, p = .000, and remaltreatment (63% vs. 34%), X2 (1, N = 10,850) = 99.8, p = .000, than children in the CWS-only group. There were more children who experienced neglect in the crossover group (90%) than in the CWS-only group (79%), X2 (1, N = 10,850) = 19.5, p = .000. A greater proportion of children in the crossover group (38%) also experienced two or more types of maltreatment than those in the CWS-only group (24%), X2 (1, N = 10,817) = 30.9, p = .000.

Family Characteristics

Family characteristics also significantly vary by crossover status. Also shown in Table 2, a greater proportion of children in the crossover group were exposed to adverse family environment characterized by parental substance use (41% vs. 24%, X2 (1, N = 10,850) = 42.8, p = .000), domestic violence (28% vs. 20%, X2 (1, N = 10,850) = 11.2, p = .001) and receipt of public assistance (78% vs. 45%, X2 (1, N = 10,850) = 119.3, p = .000) than children in the CWS-only group.

Estimating Risk of CWS-JJS transition

We conducted two separate Cox regression models with child, case, and family characteristics as predictors of risk for CWS-JJS transition. In Model 1, we included maltreatment subtypes as a measure of maltreatment severity and in Model 2 we included the number of maltreatment subtype as a measure of maltreatment severity.

As shown in Table 3, Model 1, the overall model was significant (X2 = 390.3 (14), p = .000). With regard to child characteristics, age, gender, and race/ethnicity were significantly associated with an increased likelihood of transition into the JJS among maltreated children referred to CPS. For every one year of increase in age at index CPS referral, the risk of transitioning into the JJS increases (HR = 1.6, CI: 1.5 – 1.7). The risk for CWS-JJS transition was greater for maltreated boys (HR = 2.9, CI: 2.1 – 3.9) than maltreated girls. Finally, Black (HR = 2.8, CI: 2.0 – 3.8) and Hispanic (HR = 1.6, CI: 1.1 – 2.2) children had greater risk of transitioning into the JJS than White children. Figure 1a depicts the cumulative hazard function of CWS-JJS transition for four racial and ethnic categories. As indicated by the significant hazard ratio for race/ethnicity, risk of CWS-JJS transition was highest for Black children, followed by Hispanic children, and lowest for White children and those with other race/ethnicity. Risk of CWS-JJS transition escalated around 40 months and continued through the duration of the study period.

Table 3.

Cox Regression Model of Predictors of Risk of CWS-JJS Transition

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| HR [95% CI] | HR [95% CI] | |

| Age at index CPS referral (years) | 1.61 [1.50 – 1.73]*** | 1.62 [1.51 – 1.73]*** |

| Gender (Female) | 2.89 [2.12 – 3.92]*** | 2.89 [2.12 – 3.92]*** |

| Race (White) | ||

| Black | 2.76 [2.02 – 3.78]*** | 2.82 [2.06 – 3.86]*** |

| Hispanic | 1.57 [1.11 – 2.21]* | 1.59 [1.12 – 2.24]** |

| Other | 1.17 [.63 – .2.19] | 1.18 [.63 – 2.20] |

| Prior Victimization (No) | 1.13 [.84 – 1.52] | 1.10 [.82 – 1.49] |

| Remaltreatment (No) | 1.91 [1.37 – 2.65]*** | 2.07 [1.49 – 2.88]*** |

| Maltreatment Subtype | ||

| Physical (zero) | 1.22 [.90 – 1.66] | -- |

| Neglect (zero) | 1.70 [1.01 – 2.90]* | -- |

| Sexual (zero) | 1.09 [.68 – 1.75] | -- |

| Other(zero) | 1.01 [.60 – 1.71] | -- |

| Maltreatment Subtype Count (One) | ||

| Two | -- | 1.05 [.76 – 1.45] |

| Three | -- | 1.66 [.95 – 2.88] |

| Four | -- | 1.46 [.35 – 6.0] |

| Parental Substance Use (No) | 1.26 [.95 – 1.67] | 1.25 [.94 – 1.66] |

| Exposure to Domestic Violence (No) | .81 [.59 – 1.11] | .83 [.61 – 1.14] |

| Receipt of Public Assistance (No) | 2.75 [1.93 – 3.92]*** | 2.81 [1.97 – 4.00]*** |

| Model Fit | X2 = 390.3 (14)*** | X2 = 388.8 (13)*** |

Note. Reference categories are shown in the parentheses

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

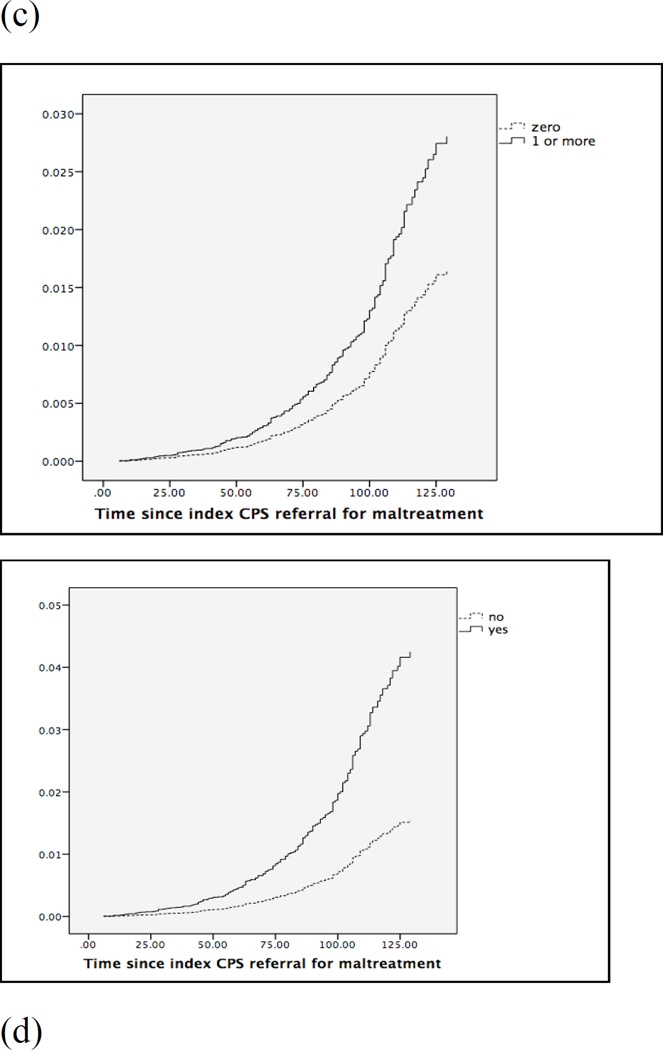

Cox proportional hazard function for (a) race/ethnicity, (b) remaltreatment, (c) neglect, and (d) receipt of public assistance.

With regard to case characteristics, experiencing remaltreatment (HR = 2.1, CI: 1.6 – 3.0) and at least one incident of neglect (HR = 1.7, CI: 1.0–2.9) were significantly associated with an increased risk of transitioning into the JJS. Figures 1b and 1c depict the cumulative hazard function of CWS-JJS transition for maltreated children who experienced subsequent maltreatment and those who did not and children who experienced at least one incident of neglect and those who did not experience neglect, respectively. Prior victimization and experiencing other types of maltreatment were not significantly associated with risk of transitioning into the JJS.

Finally, of the family characteristics, only receipt of public assistance (HR = 2.9, CI: 2.0 – 4.1) was significantly associated with CWS-JJS transition. Figure 1d depicts the cumulative hazard function of CWS-JJS transition for maltreated children living with families who received public assistance. Neither exposure to domestic violence nor parental substance use contributed significantly to risk of transition into the JJS.

The same pattern of findings was seen in Model 2, which included the number of maltreatment subtype as a measure of maltreatment severity. Age at index CPS investigation (older), gender (boys), race/ethnicity (Black and Hispanic), remaltreatment, and receipt of public assistance were significantly associated with increased risk in CWS-JJS transition. However, maltreatment severity as measured by the number of maltreatment subtype did not significantly predict risk of CWS-JJS transition.

Discussion

This study prospectively examined the transition from CWS into the JJS and how patterns of risks, including chronicity and severity of maltreatment, adverse family environment, and social risk factors, relate to CWS-JJS transition among maltreated children and adolescents. Three primary findings emerged. First, almost 3% (n = 275) of maltreated children in our sample transitioned from the CWS into the JJS and had their first JJS adjudication within an average of six years of their initial involvement in the CWS. Second, chronicity and type of maltreatment predicted risk of CWS-JJS transition. Children who experienced remaltreatment and at least one incident of neglect during the course of the study period were at greater risk for JJS involvement than children who did not experience remaltreatment or neglect. Finally, social risk factors, including a child’s age (older), gender (boys), and race/ethnicity (Black and Hispanic), as well as a family environment characterized by poverty, significantly predicted increased risk for CWS-JJS transition.

Prevalence of CWS-JJS transition: Initial juvenile justice adjudication

Although ample evidence supports the link between maltreatment and delinquency, with estimates suggesting that one-third or more of maltreated children are subsequently involved in delinquent behaviors (Postlethwait et al., 2010; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 2002), studies generally do not use prospective cohort designs. Using such a design, our findings showed that almost 3% of maltreated children were formally involved with the JJS within an average of six years of their initial referral to CPS for maltreatment. All children were between the ages of 12–17 during their initial JJS involvement, with an average age of 14. Comparable rates for the CWS to JJS transition have been found in other studies (Huang et al., 2012; Jonson-Reid & Barth, 2000; Ryan, Herz, Hernandez, & Marshall, 2007), with any variation in rates partly due to differences in JJS involvement. For example, Ryan et al. (2007) used first arrest records over a 4-year period and found that 7% of CWS-involved youth were subsequently involved in the JJS whereas Huang and colleagues (2012) found that 2% of CPS-involved youth had subsequent JJS involvement in over a 5-year period. Our measure of JJS involvement included formally adjudicated cases; maltreated children whose cases were handled informally or were diverted to less restrictive sanctions were not captured in our data but may have been included in other previous studies.

Future research should examine prevalence rates for initial as well as subsequent involvement in the JJS among maltreated children using various measures of JJS involvement (e.g., arrest, petitions, and diversion). Such studies can inform case planning and treatment efforts to address the diverse needs of crossover youth. In addition, prevalence studies can also inform potential disparities in dispositional handling of crossover youth. For example, evidence suggests that crossover youth receive harsher juvenile justice dispositions, such as recommendations for stay in secure correctional facilities even after controlling for important risk factors (Jonson-Reid & Barth, 2000; Ryan et al., 2007).

Chronicity and Severity of Maltreatment and CWS-JJS Transition

Our findings also extend the current literature by examining the impact of chronicity and severity of maltreatment on CWS-JJS transition. Nearly two-thirds of maltreated children in our study who transitioned from CWS into the JJS experienced remaltreatment. These children were about twice as likely to transition into the JJS than children who did not experience remaltreatment. This indicates that repeat and chronic maltreatment is a critical risk factor for delinquent behaviors (Logan-Greene, & Jones, 2015). Although we were not able to examine the mechanism by which chronicity of maltreatment contributes to the CWS-JJS transition, we suspect that repeat maltreatment has serious consequences that can undermine a child’s healthy development (Fluke, Shusterman, Hollinshead, & Yuan, 2008). For example, by-products of repeat maltreatment, such as multiple living transitions and unstable family relationships, are linked to problem behaviors among maltreated children (Connell et al., 2007), and may exacerbate the risk for delinquency and transition from the CWS into the JJS.

Our findings also showed that a greater proportion of children in the crossover group experienced one or more types of maltreatment than children in the CWS-only group (38% vs. 24%, respectively). However, severity of maltreatment as operationalized by the number of different types of maltreatment experienced by a child did not significantly predict the risk of transition into the JJS. Other studies have found that experiencing more than one type of abuse during childhood and adolescence is associated with increased involvement in delinquency (Arata, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & Farrill-Swails, 2005). Many studies, however, have also focused not just on the count of maltreatment types but the specific combination of different types of abuse (Naar-King, Silvern, Ryan, & Sebring, 2002). For example, evidence shows that combined sexual and physical maltreatment have the greatest impact on substance use and internalizing symptoms among maltreated adolescents (Moran, Vuchinich, & Hall, 2004). Thus, it possible that the number of types of abuse may relate to more negative behavioral outcomes particularly for children and adolescents who experience more severe combinations of different types of abuse.

Physical abuse and neglect were the most common types of maltreatment experienced by children in both the CWS-only and crossover groups. However, our findings indicated that more children in the crossover group experienced physical abuse and neglect compared to children in the CWS-only group. Neglect, in particular, significantly predicted increased risk of transition into the JJS after accounting for child, family, and case characteristics, including incidents of other types of maltreatment. This finding is consistent with research suggesting that neglect strongly predicted involvement in delinquent behaviors relative to other types of abuse among high-risk adolescents (Dembo et al., 1998; Kingree, Phan, & Thompson, 2003). Although physical abuse has received significant attention in maltreatment and delinquency research (Dodge et al., 1990; Widom, 1989a, 1989), the mechanism by which neglect contributes to delinquency is less studied, however (see Ryan et al., 2013). Frequently defined as “the failure of a parent or other person with responsibility for the child to provide needed food, clothing, shelter, medical care, or supervision to the degree that the child’s health, safety, and well-being are threatened with harm” (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016), inadequate financial resources and supervision or monitoring are often interrelated with neglect. As described in our next set of findings, transition into adolescence appears to be a critical period in which maltreated children are at greater risk of transition into the JJS. The extent to which parents or caregivers are unable to provide adequate supervision particularly during the critical period of transition into adolescence, may pose as a significant risk factor for a child’s involvement in the JJS.

Social Risk Factors: Disparities in CWS-JJS Transition

Our results showed that social risk factors significantly predicted the risk of transition into the JJS among maltreated children and adolescents. Our finding that older children were more likely to transition from the CWS into the JJS was consistent with our hypothesis that as children grow older, they experience more restrictive responses to problem behaviors, including involvement of the JJS (Woolard & Scott, 2009; Scott & Steinberg, 2008). In addition, developmental changes during the transition into adolescence, including impulsivity, susceptibility to peer pressure, and a greater sense of autonomy (Steinberg, 2008) may also place older children at greater risk of involvement in the JJS. Further, our finding that boys compared to girls were more likely to transition into the JJS is consistent with studies suggesting that boys are more likely to experience between-systems transition than girls (Graves et al., 2005; Ryan et al., 2013). Although we were not able to examine the mechanisms by which gender contribute to the risk of CWS-JJS transition, research suggests that adverse consequences of maltreatment among boys are manifested in externalizing behaviors (Topitzes et al., 2011) and in some instances, violent offending (Asscher et al., 2015), whereas girls are more likely to show internalizing symptoms (Topitzes et al., 2011). Boys also engage in chronic delinquent behaviors more so than girls (Miller et al., 2010), which may result to a greater likelihood of involvement in the JJS.

Our findings also showed that compared to White children, Black children had more than twice the risk of experiencing a CWS-JJS transition, even after accounting for different case and family characteristics. Hispanic children also had a greater risk of transitioning into the JJS compared to White children. These findings are consistent with well-documented disparities for racial and ethnic minority youth in different service systems (Bishop, et al., 2010; Putnam-Hornstein, Needell, King, & Johnson-Motoyama, 2013), and particularly in the JJS (Davis & Sorensen, 2013) and at almost every stage of juvenile justice processing (Bishop et al., 2010; Peck & Jennings, 2016).

Our findings extend previous studies indicating that racial and ethnic minority youth with a history of CWS involvement are disproportionately referred to the JJS (Goodkind, Shook, Kim, Pohlig, & Herring, 2013; Graves et al., 2007; Johnson-Reid & Barth, 2000; Ryan et al, 2013; Tam, Abrams, Freisthler, & Ryan, 2016). This is troubling given evidence showing that Black and Hispanic crossover youth are also more likely to be rearrested compared to White crossover youth (Huang et al., 2012). Importantly, these findings remain even after accounting for critical risk factors, such as history of arrest, home environment, peer association, school attendance, and receipt of mental health and substance abuse services (Goodkind et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2013).

Although we were not able to characterize the mechanisms by which racial and ethnic disparities operate in CWS-JJS transition, research on the effect of race on attributions to and perceptions of dangerousness and risk provide some insight. Several studies have shown that delinquent behavior among minority youth is more likely attributed to a character flaw and perceived to be dangerous so as to result in recommendations for harsher punishment (Graham & Lowery, 2004; Bridges & Steen, 1998; Gilliam & Iyengar, 1988). Further research is needed to understand what factors contribute to racial and ethnic disparities among crossover youth and ways by which disparities may be reduced at various key decision-making points in the system (e.g., arrest, intake, adjudication, dispositional hearing). Results may prioritize efforts for culturally competent training and practices.

Family and Home Environment: The Influence of Poverty

Economic hardship characterized by receipt of public assistance significantly increased the risk of CWS-JJS transition among maltreated children and adolescents. Families living in poverty experience multiple cumulative stressors, thus straining familial resources and relationships (Booth & Anthony, 2015). Indeed, poverty has been associated with a multitude of negative outcomes, including repeat maltreatment (Connell, et al., 2007), poor academic achievement (Herbers et al., 2012), mental health problems (Nikulina, Widom, & Czaja, 2011), and delinquency (Booth & Anthony, 2005; Najman et al., 2010). For maltreated children and adolescents, the negative impact of economic hardship may be even more pronounced given that they often experience persistent and prolonged poverty (Connell et al., 2007; Nikulina et al., 2011). Our finding that receipt of public assistance significantly increased the risk for CWS-JJS transition even after accounting for important child, case, and other family characteristics calls for interventions to help alleviate the negative impact of economic hardship. Services for maltreated children and families are often tailored to prevent further maltreatment and address the consequences of maltreatment, including mental and behavioral health problems and trauma (Swenson, Schaeffer, Henggeler, Faldowski, & Mayhew, 2010). However, a metasystems approach that takes into account “contexts and environments” that promote a child’s adaptation and development (Kazak et al., 2010) may better serve maltreated children and their families, particularly those at-risk for transitioning into the JJS.

Limitations

There are several limitations to keep in mind when interpreting these results. First, our regression analyses were correlational, and thus causality cannot be inferred. Relatedly, although the findings show significant associations between risk factors, including social risks, recurrence of maltreatment, and poverty, and the CWS-JJS transition, the mechanisms by which these relationships operate were not examined directly. Second, our utilization of administrative data limits the extent to which we are able to characterize the chronicity and severity of maltreatment. For example, previous studies have also included the context of maltreatment, such as degree of force used and injuries that resulted, and relationship of child to perpetrator when conceptualizing maltreatment severity (DiLillo et al., 2010). The use of administrative data also limited the types of variables available for study. For example, although it is unlikely, it is possible that some children and adolescents had previous juvenile justice involvement through diversion or less restrictive sanctions prior to the age of 10, which would not have been captured in the data. Third, we were not able to track specific services received by our sample of maltreated children and their families. The extent to which maltreated children and families have access to and receive specific services could have altered the negative outcomes associated with the various risks experienced (DePanfilis & Zuravin, 1999).

Conclusion

Overall, this prospective study indicated that almost three percent of maltreated children are adjudicated delinquent within an average of six years of their initial CPS investigation, and that social risk factors, including a child’s age (older), gender (boys), and race/ethnicity (Black and Hispanic), as well as a family environment characterized by poverty significantly predicted the risk of CWS-JJS transition. These findings have important implications for developing and tailoring services for crossover youth. Promoting culturally sensitive training and practices among CWS and JJS staff may help better address the unique needs and experiences of minority children and adolescents, and targeting poverty as a key risk factor in the CWS-JJS transition may encourage a more comprehensive, meta-systems approach that includes the provision of support services to parents and family (Pennell, Shapiro, & Spigner, 2001). Such a comprehensive approach may also help reduce the negative outcomes from maltreatment and prevent subsequent JJS involvement.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded, in part, by the Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF) in support of the Rhode Island Data Analytic Center, a collaborative endeavor of Rhode Island DCYF and the Yale University School of Medicine, and by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32 DA 019426; JK Tebes). We would like to thank Leon Saunders and David Allenson from Rhode Island DCYF and Maegan Genovese from the Yale University School of Medicine for their technical support of the administrative data used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah Vidal, Westat

Dana Prince, Case Western Reserve University

Christian M. Connell, Yale University School of Medicine

Colleen M. Caron, Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, and Families

Joy S. Kaufman, Yale University School of Medicine

Jacob K. Tebes, Yale University School of Medicine

References

- Aneshensel CS. Toward explaining mental health disparities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:377–394. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen M, Sroufe LA. When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, O’Farrill-Swails L. Single versus multi-type maltreatment: An examination of the long-term effects of child abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2005;11(4):29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Asscher JJ, Van der Put CE, Stams GJJ. Gender differences in the impact of abuse and neglect victimization on adolescent offending behavior. Journal of family violence. 2015;30(2):215–225. doi: 10.1007/s10896-014-9668-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Wolff KT, Piquero AR, Epps N. The relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and juvenile offending trajectories in a juvenile offender sample. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2015;43:229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Aggression: A social learning analysis. Prentice-Hall. 1973 [Google Scholar]

- Bauman LJ, Silver EJ, Stein RE. Cumulative social disadvantage and child health. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1321–1328. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA. Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(1–2):35–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1023018502759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DM, Leiber M, Johnson J. Contexts of decision making in the juvenile justice system: An organizational approach to understanding minority overrepresentation. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2010;8:213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Booth JM, Anthony EK. Examining the interaction of daily hassles across ecological domains on substance use and delinquency among low-income adolescents of. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Bridges GS, Steen S. Racial disparities in official assessments of juvenile offenders: Attributional stereotypes as mediating mechanisms. American Sociological Review. 1998:554–570. [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. Definitions of child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau; 2016. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/statutes/define/ [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children-past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:402–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Bergeron N, Katz KH, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Re-referral to child protective services: The influence of child, family, and case characteristics on risk status. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(5):573–588. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Vanderploeg JJ, Katz KH, Caron C, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Maltreatment following reunification: Predictors of subsequent Child Protective Services contact after children return home. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N, Baker AJ, Anastasio E, Purcell J. Characteristics of children in residential treatment in New York State. Child Welfare. 2007;86:5–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Sorensen JR. Disproportionate minority confinement of juveniles A national examination of black-white disparity in placements, 1997–2006. Crime & Delinquency. 2013;59:115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Schmeidler J, Nini-Gough B, Sue CC, Borden P, Manning D. Predictors of recidivism to a juvenile assessment center: A three-year study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1998;7(3):57–77. [Google Scholar]

- DePanfilis D, Zuravin SJ. Predicting child maltreatment recurrences during treatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:729–743. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Hayes-Skelton SA, Fortier MA, Perry AR, Evans SE, Moore TLM, Fauchier A. Development and initial psychometric properties of the Computer Assisted Maltreatment Inventory (CAMI): A comprehensive self-report measure of child maltreatment history. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250(4988):1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development. 2008;79:1907–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jonson-Reid M, Way I, Chung S. Substantiation and recidivism. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:248–260. doi: 10.1177/1077559503258930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Yeung WJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Smith JR. How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review. 1998;63:406–423. [Google Scholar]

- Fluke JD, Shusterman GR, Hollinshead DM, Yuan YYT. Longitudinal analysis of repeated child abuse reporting and victimization: Multistate analysis of associated factors. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:76–88. doi: 10.1177/1077559507311517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam FD, Jr, Iyengar S. Prime suspects: The influence of local television news on the viewing public. American Journal of Political Science. 2000;44:560–573. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Lowery BS. Priming unconscious racial stereotypes about adolescent offenders. Law and Human Behavior. 2004;28:483–504. doi: 10.1023/b:lahu.0000046430.65485.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind S, Shook JJ, Kim KH, Pohlig RT, Herring DJ. From child welfare to juvenile justice race, gender, and system experiences. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2013;11:249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Graves KN, Frabutt JM, Shelton TL. Factors associated with mental health and juvenile justice involvement among children with severe emotional disturbance. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2007;5:147–167. [Google Scholar]

- Haight W, Bidwell L, Choi WS, Cho M. An evaluation of the Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM): Recidivism outcomes for maltreated youth involved in the juvenile justice system. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;65:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Herbers JE, Cutuli JJ, Supkoff LM, Heistad D, Chan CK, Hinz E, Masten AS. Early reading skills and academic achievement trajectories of students facing poverty, homelessness, and high residential mobility. Educational Researcher. 2012;41:366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Herz D, Lee P, Lutz L, Stewart M, Tuell J, Wiig J. Addressing the needs of multisystem youth: Strengthening the connection between child welfare and juvenile justice. Center for Juvenile Justice Reform. 2012 http://cjjr.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MultiSystemYouth_March2012.pdf.

- Herz DC, Ryan JP, Bilchik S. Challenges facing crossover youth: An examination of juvenile-justice decision making and recidivism. Family Court Review. 2010;48:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Ryan JP, Herz D. The journey of dually-involved youth: The description and prediction of rereporting and recidivism. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Jarjoura GR, Triplett RA, Brinker GP. Growing up poor: Examining the link between persistent childhood poverty and delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2002;18:159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Barth R. From placement to prison: The path to adolescent incarceration from child welfare supervised foster or group care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2000;224:493–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE, Hoagwood K, Weisz JR, Hood K, Kratochwill TR, Vargas LA, Banez GA. A meta-systems approach to evidence-based practice for children and adolescents. American Psychologist. 2010;65:85–97. doi: 10.1037/a0017784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingree JB, Phan D, Thompson M. Child maltreatment and recidivism among adolescent detainees. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2003;30(6):623–643. [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Harold GT, Chamberlain P, Landsverk JA, Fisher PA, Vostanis P. Practitioner review: Children in foster care-vulnerabilities and evidence- based interventions that promote resilience processes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:1197–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell JH, Schuerman JR. What works best for whom? A closer look at intensive family preservation services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2002;24:673–699. [Google Scholar]

- Logan-Greene P, Semanchin Jones A. Chronic neglect and aggression/delinquency: A longitudinal examination. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;45:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Topitzes J, Reynolds AJ. Unsafe at any age linking childhood and adolescent maltreatment to delinquency and crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2012;49:295–318. doi: 10.1177/0022427811415284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Malone PS, Dodge KA Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Developmental trajectories of boys’ and girls’ delinquency: Sex differences and links to later adolescent outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:1021–1032. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9430-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran PB, Vuchinich S, Hall NK. Associations between types of maltreatment and substance use during adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moylan CA, Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Russo MJ. The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Silvern L, Ryan V, Sebring D. Type and severity of abuse as predictors of psychiatric symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17(2):133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Clavarino A, McGee TR, Bor W, Williams GM, Hayatbakhsh MR. Timing and chronicity of family poverty and development of unhealthy behaviors in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina V, Widom CS, Czaja S. The role of childhood neglect and childhood poverty in predicting mental health, academic achievement and crime in adulthood. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(3–4):309–321. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9385-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck JH, Jennings WG. A critical examination of “being Black” in the juvenile justice system. Law and Human Behavior. 2016;40:219–232. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell J, Shapiro C, Spigner C. Safety, fairness, stability: Repositioning juvenile justice and child welfare to engage families and communities. 2011 Center for Juvenile Justice Reform http://cjjr.georgetown.edu/pdfs/famengagement/FamilyEngagementPaper.pdf.

- Postlethwait AW, Barth RP, Guo S. Gender variation in delinquent behavior changes of child welfare-involved youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:318–324. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Needell B, King B, Johnson-Motoyama M. Racial and ethnic disparities: A population-based examination of risk factors for involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, Herz D, Hernandez PM, Marshall JM. Maltreatment and delinquency: Investigating child welfare bias in juvenile justice processing. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29:1035–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, Testa MF. Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27:227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, Williams AB, Courtney ME. Adolescent Neglect, Juvenile Delinquency and the Risk of Recidivism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:454–465. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9906-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A, Seifer R, Zax M, Barocas R. Early indicators of developmental risk: Rochester Longitudinal Study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13:383–394. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott ES, Steinberg L. Adolescent development and the regulation of youth crime. The Future of Children. 2008;18:15–33. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Ireland TO, Thornberry TP. Adolescent maltreatment and its impact on young adult antisocial behavior. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:1099–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental review. 2008;28(1):78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Wei EH, Homish DL, Loeber R. Which family and demographic factors are related to both maltreatment and persistent serious juvenile delinquency? Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice. 2002;5:261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson CC, Schaeffer CM, Henggeler SW, Faldowski R, Mayhew AM. Multisystemic Therapy for Child Abuse and Neglect: a randomized effectiveness trial. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:497–507. doi: 10.1037/a0020324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam CC, Abrams LS, Freisthler B, Ryan JP. Juvenile justice sentencing: Do gender and child welfare involvement matter? Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;64:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Topitzes J, Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ. Child maltreatment and offending behavior gender-specific effects and pathways. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2011;38(5):492–510. doi: 10.1177/0093854811398578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect, and violent criminal behavior. Criminology. 1989a;27:251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychological Bulletin. 1989b;106:3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolard JL, Scott E. The legal regulation of adolescence. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2009 [Google Scholar]