Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to evaluate end user perspectives of four existing home access solutions (HAS) and a newly designed experimental device (the ARISE).

Method

A cross-sectional design was used to evaluate the ARISE prototype against other HAS. Specifically, participants trialed stairs, a ramp, a platform lift (PL), a stair glide and the ARISE, after which they completed questionnaires aimed at soliciting their perspectives of these solutions. The time taken by participants to use each HAS was also collected.

Results

Five HAS design features were deemed as important by 90% of participants: ease of use, ability to use independently, reliability, safety and security. Time taken to use each HAS from fastest to slowest was: stairs, the ARISE, ramp, PL and stair glide. The ARISE prototype was rated as the first or second most preferred device by the most number of participants, followed by the PL, then the ramp.

Conclusions

Results from this study provide greater understanding of user perspectives of HAS. End user feedback on a novel prototype device has provided valuable insight into its usability and function, which should not only guide future development of this device, but also provide direction for other innovations around home access.

Keywords: Accessibility, aging in place, evaluation, home access, independent living, usability, user-centred design

Background

Stairways into buildings have been reported amongst the most challenging environmental barriers for users of wheeled mobility devices [1]. Further, older adults have identified stair climbing as the activity most requiring assistive devices [2]. The significance of this problem should not be underestimated. Reporting on findings from the National Health Interview Survey and the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation, Maisel et al. note that approximately 1.7–2.3 million people in the US use wheeled mobility devices and an additional 6.1 million individuals use other devices, such as canes, crutches or walkers. Quoting statistics from the National Center for Health Statistics 2006, Maisel also notes that in the US, 11.5 million persons aged 65 and older reported difficulty climbing 10 steps without resting [3].

With estimates of home inaccessibility as high as 90% in the US [3], home access presents a significant barrier to people with mobility impairments and those wanting to age-in-place [4–7]. Traditional solutions to address home inaccessibility have typically involved either moving to alternate housing or modifying the home to remove accessibility barriers [3]. The complex challenges associated with a move and the failure of many to adequately modify their homes [8] have serious implications for people with mobility limitations. Inaccessible housing has been associated with premature institutionalization, increased care costs, deteriorating health and well-being, dislocated family relations and recourse to higher dependency housing [3,9–11].

Home access solutions (HAS) aim to address the architectural barrier that stairs present and allow users to safely enter and exit the home while maintaining as much independence as possible [8]. Existing HAS range from relatively inexpensive handrails and ramps to more costly elevators and lifts. Lifts can be categorized into three broad groups: (1) vertical platform lifts (PLs) –designed to transport the user vertically between 2 and 3 floor levels; (2) inclined PLs (also referred to as a wheelchair PLs) –designed to transport the user between levels on an incline, such as along a stairway and (3) stair glides (also referred to as stair lifts, stair-chair lifts and stair climbers) – designed to transport a seated user between floor levels while traveling on an incline, such as along a stairway [12]. It is apparent that innovation in HAS over recent years is limited; the changing demographics have done little to spur innovation in this area, and these “traditional” HAS that have been used for many years continue to dominate the market. While a few new solutions have been developed in recent years [13–15], the uptake of these solutions is limited to specific niche applications.

Studies looking at the benefits and limitations of “traditional” HAS point to several drawbacks with these solutions. While ramps typically offer a lower cost access solution, their large foot print and impact on home aesthetics limits the locations in which they can be used and reduces their desirability for many [16,17]. Safety concerns, such as the grade of the ramp, challenges negotiating tight ramp corners and the effects of weather on ramp slipperiness, have also been reported [17–19]. Elevators have been identified as effective solutions in terms of speed, capacity, rise and usability, however the need for adequate space, and the high costs associated with their purchase, installation and maintenance are significant drawbacks, thus limiting their use in typical home settings [12]. PLs and stair glides remain the “devices of choice” for small elevation changes [12] in existing homes however these also have their limitations. For PLs, limitations relating to use, size, speed, capacity and rise have been identified [12]. For stair glides, the need to transfer on and off the chair (often at the top of the stairs – one of the most dangerous places in a house) poses risks for those with transfer, balance or visual limitations [20], and the fact that they do not provide access for wheeled mobility devices limits their usability for many [12]. In addition, anecdotally, stair glides do not provide quality access, marginalizing individual dignity with their slow cumbersome use.

Two other significant drawbacks inherent with existing HAS are their lack of inclusivity and the fact that they appear to many as obvious symbols of disability. These have been reported to negatively impact the self-identity of residents and their relationship with neighbours, as well as make residents feel less secure, even vulnerable [21,22]. It has been suggested that these factors may compromise the functionality and expected benefits of HAS [21].

Given the drawbacks of the existing solutions, a new HAS solution has recently been developed: the ARISE – an integrated staircase-lift prototype. This novel design aims to: address inclusivity by providing a staircase and lift in the same access location and footprint; encourage stair use whenever possible (e.g. by seniors for exercise), as well as offer the safety and convenience of a lift when necessary (e.g. when the person is encumbered or using a wheelchair); be substantially quicker to use than currently available solutions and provide repeatable emergency descent from a house in times of power outages. The device allows for use of stairs or the lift to access the same entrance whether walking, using a wheelchair, using a walker or pushing a stroller.

The ARISE was designed to be constructed side-ways adjacent to a front porch of a house. A lift platform to accommodate a wheelchair is hinged to either end of the staircase. This entire symmetrical structure pivots about the centre of the stairs in the manner of a “see-saw”, with a parallelogram linkage operating to maintain each of the platforms horizontal at all times. A person (e.g. in a wheelchair or otherwise) can enter either the top or bottom staircase platform, thus there is never a need to “call” or wait for the platform. A fully functioning prototype was fabricated for user testing, with aesthetic details considered to make the ARISE look as close as possible to a commercially available product. Further details of the ARISE prototype development have been reported elsewhere [23].

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate end user perspectives of existing HAS for access to a raised landing of a house (e.g. front porch). A secondary objective of the study was to document the end user perspectives of the ARISE compared to these exemplary home access products. In particular, we aimed to get user perspectives of these HAS with respect to usability, operation, aesthetics, safety and security.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional design was used to evaluate the ARISE prototype against other HAS. Specifically, participants were asked to trial five different HAS (including the ARISE), after which they were asked to complete a set of questionnaires aimed at soliciting their perceptions of these solutions.

Sample

Participants with a range of ages and mobility limitations (e.g. those who used canes, walkers, manual and power wheelchairs) were recruited for the study. Subject inclusion criteria included: challenges getting in and out of buildings and homes with entryways that are not at ground level; physical condition that limits mobility; ability to communicate effectively in English and a combined weight of participant + mobility device less than 400 lbs. Exclusions included: hand function limitations that would affect ability to press buttons or switches; and health problems that would interfere with participation in the study.

Participants were recruited through flyers posted at rehabilitation centres, disability groups and seniors’ organizations, as well as via community contacts and word of mouth. Participants who had previously participated in a focus group conducted by our team on HAS (including the ARISE) were also contacted. Participants were purposively sampled to maximize the range of different disability groups, ages and assistive device use.

Measurements

Frenchay’s Activity Index (FAI-15) and a Preliminary Questionnaire were used to gather participant information to better describe the sample. The FAI-15 is a scale comprising 15 individual activities summed to give an overall score from 0 (low) to 45 (high). While it was developed primarily to assess the functional status in stroke patients [24,25], the potential of using it to assess instrumental activities of daily living with other disability groups has also been demonstrated [26].

The Preliminary Questionnaire (developed by our team) was used to collect basic demographics and information specifically related to home access (e.g. existing living arrangements and details about existing HAS). This questionnaire also includes a section where participants are asked to rate the importance of 21 different features of HAS (e.g. related to usability, operation, aesthetics, safety and security) to provide insight into user prioritization of these features. Features included in this questionnaire were determined based on themes that emerged during previous studies that involved focus groups and interviews with end users and occupational therapists [27,28]. All features are rated on a Likert scale of 1–5 (from not important at all to extremely important).

We also developed an Evaluation Questionnaire to solicit participant perceptions for each HAS after it had been trialed. The Evaluation Questionnaire (administered for each solution) includes satisfaction ratings for the 21 HAS features (the same features included in the Preliminary Questionnaire), rated on a Likert scale of 1–5 (from not satisfied at all to very satisfied). In addition, the Evaluation Questionnaire solicits feedback on costs, as well as open-ended feedback on what they liked best and least, and suggestions for improvement.

Finally, we developed an Exit Questionnaire (administered at the end of the trial) that asks participants to rank all of the solutions they evaluated by overall preference.

Questionnaires that were developed by the team were piloted with three individuals prior to the study to identify issues relating to wording, question clarity and timing.

Data collection

The study was approved by our Ethics Review Board which complies with the guidelines set out by the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS2).

The fully functioning ARISE was installed onto a wooden “porch” built inside our evaluation lab (Figure 1). Four other HAS were installed onto the porch: a staircase with five stairs, a ramp (built at 1:12 grade), a Bruno Elite stair glide and a Savaria PL (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

ARISE home access solution installed on “porch” in the evaluation lab.

Figure 2.

Evaluation set up showing (from left to right) stair glide, staircase with five stairs, 1:12 grade ramp, and platform lift.

Evaluation sessions were approximately 2 h long. All questionnaires were administered by a member of the research team using an online survey tool (FluidSurveys™) to facilitate data entry and analysis. All sessions were video recorded for later review.

At the beginning of each session, participants were welcomed, the study protocol was explained and informed consent forms were signed. Participants were asked to complete the FAI-15 and the Preliminary Questionnaire. Participants were given an overview of all HAS installed in the lab. The selection of HAS for each participant to evaluate was determined by asking participants about their ability to use the solution comfortably and safely. When needed, participants were given a demonstration of how to use each HAS prior to trying it themselves. They were told to use each HAS at a comfortable speed (not racing), and were invited to take rests and breaks whenever necessary. Furthermore, participants were told that the researchers did not have any investment or preferences for any of the solutions being evaluated, and were reminded throughout the evaluation to be critical of the solutions they were testing. The order in which the solutions were trialed was randomized in order to minimize order effect.

While participants tried each HAS, participant comments (e.g. “it would be good to have a place for my cane or a purse”) and researcher observations (e.g. “participant had difficulty holding down control button while holding canes”) were noted. In addition, ascent/descent times were recorded. Times were calculated based on pre-determined start and stop criteria and included rest times if rests were taken before the end point was reached. In most cases, timing variables reflect participants using the solutions independently, however in cases where it became apparent that the participant would be unable to use the solution without help (e.g. with the seatbelt on the Stair Glide), a researcher provided assistance (type of assistance was noted in the study documents).

After using each HAS, participants were asked to complete the Evaluation Questionnaire. Finally, the Exit Questionnaire was completed at the end of the study.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (e.g. proportions, means and standard deviations) were used to describe Likert scale rating questions. Ratings on the 5-point Likert scale were collapsed into three categories (e.g. satisfied/neutral/not satisfied, or important/neutral/not important) to get a representation of general tendency of satisfaction or importance. For example, questions rated as 5 (very satisfied) and 4 (more or less satisfied) were analyzed together as “satisfied”, while questions rated as 2 (not very satisfied) and 1 (not satisfied at all) were analyzed together as “unsatisfied”. Questions rated as “3” were analyzed as neutral. Importance ratings were combined in a similar fashion.

Responses to open-ended questions, participant comments and researcher observations from the trials were coded and collapsed into themes. Ascent/descent times were described using descriptive statistics.

Results

Participant characteristics

A sample of 30 participants with a range of ages and mobility limitations (including 17 subjects using wheelchairs) were recruited (see Table 1 for detailed participant characteristics). Most participants (N = 18) lived in an apartment or condominium, and most (N = 17) had level access to the ground. Of those who did not have level access, 10 used a ramp to gain entry to their home.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and FAI-15 score.

| Participant characteristics (N = 30) | N or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Range = 24–83 | 47.9 ± 17.4 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 18 |

| Male | 12 |

| Primary disability | |

| SCI (T12-C4-5) | 9 |

| Arthritis/aging | 7 |

| Stroke | 3 |

| Other: CP, MS, post-polio, amputee | 10 |

| Primary mobility device used in the communitya | |

| Manual wheelchaira | 8 |

| Power (or power assist) wheelchair/scooter | 10 |

| Cane/crutches/walker | 11 |

| No assistive technology | 1 |

| FAI score | |

| Range = 28–53 | 42.6 ± 6.4 |

Several participants used more than one type of assistive technology (AT) for mobility (e.g. both power and manual chairs, or scooters with canes or walkers for shorter distances). For the study they were asked to use the AT they use most commonly when navigating in the community. The exception was when a user had a power wheelchair or scooter that was too heavy or too large for the lifts in the study. In this case they were asked to use the other AT (e.g. a manual chair or canes), if possible.

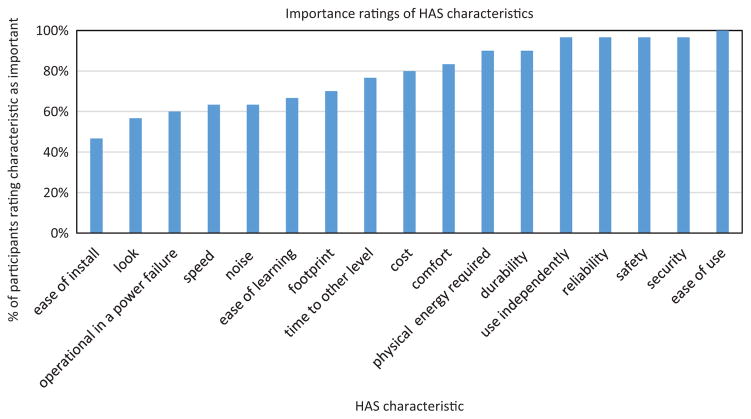

Design features ratings

Seventeen characteristic HAS design features were surveyed for perceived importance (see Figure 3). Five features were rated as “important” (i.e. important or very important on the Likert scale) by greater than 90% of participants: ease of use, ability to use independently, reliability, safety and security. Four other features were rated important by between 80% and 90% of participants: cost, comfort, physical energy required to use and durability. Participants were also asked to list the three characteristics of HAS they considered to be the most important. In this case, safety was rated in the top three list more than any other characteristic, followed by reliability, then cost.

Figure 3.

Design feature ratings of HAS characteristics, showing the number of participants rating each HAS characteristic as important (i.e. either “extremely important” or “quite important”).

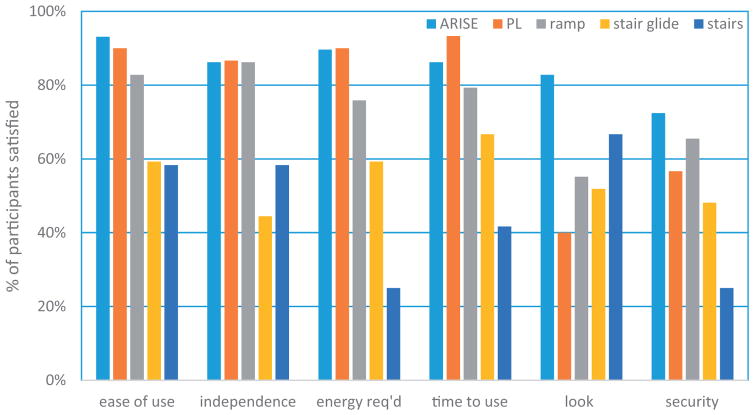

Participant perceptions

Key findings of the satisfaction ratings from the Evaluation Questionnaires are presented in Figure 4, illustrating the percentage of participants who used each solution that were satisfactied with a number of HAS features. Key results from the Evaluation Questionnaires are summarized with participant comments and researcher observations for each HAS below.

Figure 4.

User satisfaction for all HAS, illustrating the percentage of participants who were satisfied (i.e. rated level of satisfaction as “very satisfied” or “satisfied”) with a range of characteristics.

Stairs

The stairs were unsurprisingly problematic for many participants and were rated poorly compared to the other HAS evaluated in this study. In particular, only three of the participants who evaluated the stairs were satisfied with the security and the physical energy required to use the stairs. Only four features were rated “satisfied” by greater than 80% of participants who evaluated this solution: ease of use, durability, reliability and noise. It should be noted that only 12 participants were able to use the stairs therefore a large number of participants did not rate this solution. Several participants who evaluated the stairs commented that they did not feel safe or stable using them, and they had concerns about falling (N = 5). Several participants also noted the considerable effort stairs required (N = 5). Specific comments were made relating to the railing of the stairs (e.g. concerns with narrowness and sturdiness of the railing, and the fact that the rail did not extend out far enough beyond the ends of the stairs to provide support to users getting on and off). The stairs were particularly problematic for those with hemiplegia who had to hold their cane in one hand while still holding on to the railing. A number of participants commented that the most favourable characteristics of the stairs were that they were reliable and durable. The benefits of the exercise the stairs provide were also brought up. Suggestions included improving the visibility of the stairs with markings and providing a non-slip surface.

Ramp

More than 80% of participants who evaluated the ramp were satisfied with ease of learning, noise, ability to use independently, reliability, ease of use and durability of the ramp. While most participants (22 of the 29 who were able to use this solution) were reasonably satisfied with the physical energy required to use the ramp, this result seemed to contradict researchers’ notes that indicated that a number of participants appeared to expend significant physical effort when using the ramp. When responses were analyzed by type of mobility aid used, a greater percentage of wheelchair users were satisfied with the physical energy required (16 of the 18 wheelchair users – i.e. 89%) when compared with those who walked or used walkers (6 of the 11 walkers – i.e. 55%). The lowest satisfaction ratings for the ramp were for footprint and look of the solution.

Participant comments about the ramp were mixed. Most participants liked that the ramp was simple, easy to use and very reliable (i.e. no moving parts and no reliance on power). They also liked that it could be used by anyone (i.e. encompassed universal design principles) and multiple people could use the solution at the same time. On the other hand, negative feedback was given about the footprint (N = 8) and the appearance of the ramp (N = 8), including the fact that it is a visibly obvious solution for a person with a disability that gives away the vulnerability of the home owner. Ramps integrated into gardens and landscape are a preferable option. Some comments about the specific ramp used in the evaluation were made – e.g. the landing was too small for switchbacks in power wheelchairs, the vertical posts in the rails were challenging to navigate around and the lack of rail continuity on both sides of the ramp posed problems for those with only the use of one hand.

Stair glide

The stair glide satisfaction ratings were low across a number of parameters. In particular, less than 25% of participants who evaluated this solution were satisfied with their ability to use it independently, and security. There were no stair glide parameters that were rated more positively than those of the other HAS.

In general, participants found the stair glide more challenging to use than the other HAS and the feedback on this solution was quite negative. The need to transfer twice for every stair glide use was one of the most significant drawbacks of this solution noted and prevented a number of wheelchair and scooter users from being able to use this solution independently (N = 12) and presented challenges for others (N = 4). The seat belt also proved challenging for many. While some participants felt the seatbelt gave them a sense of security, many participants struggled with reaching the straps and attaching the belt (especially hemiplegic participants and those with a large girth). Other negative comments were made about the speed of operation, the look (like something a “granny” would use), the size and ricketiness of the seat, as well as the limited capacity for the user to carry things (including mobility aids). Participants with limited leg function or spasticity also noted challenges keeping feet in position on the footplates. Researchers observed that this posed a serious hazard as feet could inadvertently get trapped between the footplate and the stairs. Leg straps or footplates that held the feet in place were suggested, although participants felt this would impact the ease of getting on and off the stair lift.

Platform lift

For the platform lift (PL), over 80% of participants were satisfied with ease of learning, time to another level, speed of operation, ease of use, physical energy required and ability to use the solution independently. The lowest satisfaction ratings for the PL were for noise and look. In general, participants found the PL was straightforward to use and had a smooth to ride. They also liked that the PL was spacious enough to accommodate mobility aids and other items. Some commented that having to continuously hold down the activation button was tiring (N = 5), and balancing while pressing the button was also challenging for some (particularly those with hemiplegia).

There were also a number of concerns about the safety of the lift (N = 11), including a pinch point at the back of the lift that could potentially injure a user’s toes. The fact that the support rail was only on one side of the PL was a problem for those with hemiplegia and for those holding a cane in one hand. Suggestions were made for more support rails, a fold up seat, a place to hold canes and a remote. The short access ramp at the front of the platform also provided safety concerns (i.e. the ramp does not come to a completely vertical position when lift moves, and on descent, the ramp starts lowering before the lift comes to rest). Even though these issues did not pose any true safety concerns, it was noted that “the feeling safety” this barrier provides is as important to the user as the actual safety of the device. The small ramp also provided an access challenge for some (N = 9) and prevented some users (N = 2) from being able to use the solution independently. Suggestions included reducing the grade of the ramp, and extending the railings past the edges of the platform to assist users walking onto the lift.

While several participants commented that they liked the compactness of the PL, in general participants did not like the look of it (N = 11), commenting that it was clinical and boxy, and participants felt “enclosed”. Participants also commented that the walls and ramp seemed flimsy. There were also comments about the number of moving parts on the PL, especially given the solution is to be used outdoors. Participants’ previous experiences with PL and the fact that the PL is reliant on power led participants to bring up reliability concerns with this solution.

ARISE

For the ARISE, over 80% of participants were satisfied with ease of use, ease learning, physical energy required, ability to use independently, time to another level and look. The lowest satisfaction ratings were scored for noise. In their comments, participants described the ARISE as innovative and “cool”. They liked that it integrated into the look of the house and several noted that it did not appear to stand out as a solution for a person with a disability (N = 17). Further, they liked that a user would not have to wait to use the solution, and that it was inclusive – i.e. it encompassed universal design principals by providing the option for anyone to use the stairs or the lift (N = 17). One user thought the ARISE might add market value to a house by providing a solution for those wanting to age in place.

Regarding the capacity of the ARISE, participants liked that the platform could accommodate groceries or other items they might have to carry however there were concerns that the ARISE did not accommodate scooters and large power chairs. As with the PL, there were comments about the fatigue and balance challenges related to the button position and the need to continuously hold it down for operation. Suggestions included providing a flip down chair, additional support rails and/or using a remote to overcome these challenges. As with the PL, the fold out ramp leading to the platform provided challenges for some (N = 6). Several participants commented that they liked the fact that the ARISE was fast, however some felt that the movement was too quick and jerky. To accommodate different preferences, it was suggested that users should be allowed to regulate the speed themselves. In addition, suggestions were made to put more substantial safety gates in place.

Comparative ratings (all HAS)

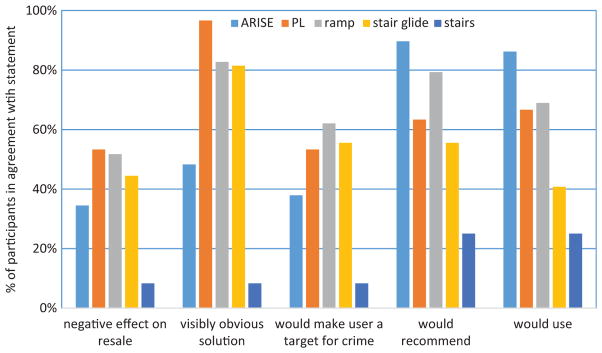

Agreement ratings

Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with several statements about each HAS evaluated (Figure 5). In general, the ARISE was rated favourably in comparison to the other solutions with respect to recommending the solution and using it if it were made available. Apart from the stairs, the ARISE was rated the best in terms of appearance as a visible solution for a person with a disability, making the user a target for criminal activity and having a negative impact on resale value of a house.

Figure 5.

Agreement ratings for all HAS, showing the percentage of participants who agree (i.e. strongly agree or somewhat agree) with a variety of statements relating to perceptions and use of the solution.

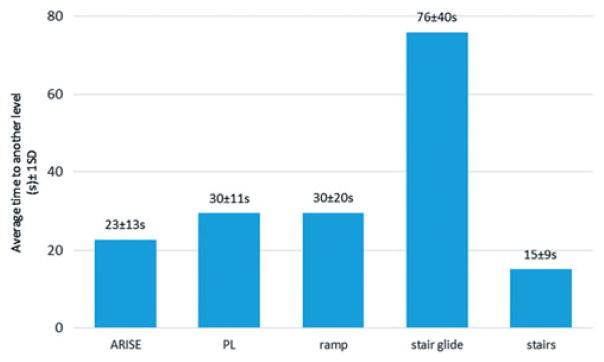

Timing variables

Results for the actual time it took participants to get to another level are presented in Figure 6. It should be noted that due to the varying physical limitations of the participants and the mobility device that they used, there were considerable variances in the individual times.

Figure 6.

Average time to another level for all HAS evaluated in the study. Times represent an average of ascent time and descent time (including time to enter/exit) for all participants.

Results showed the stairs were the fastest HAS (for those able to use them), followed by the ARISE. The stair glide was the slowest solution.

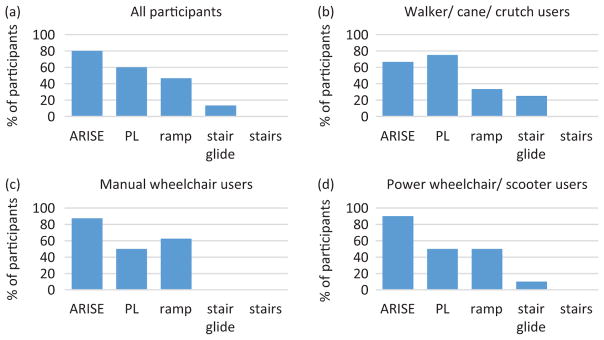

Overall preference ratings

The percentage of participants rating each of the HAS as their first or second favourite solution is presented in Figure 7. The ARISE was rated first or second by the most number of participants (N = 24), followed by the PL (N = 18), then the ramp (N = 14). The stairs and the stair glide were rated the least favourable.

Figure 7.

Overall preference of HAS for (a) all participants, (b) those who used walkers, canes or crutches, (c) manual wheelchair users and (d) power wheelchair and scooter users. Graphs represent the percentage of participants who rated the solution in their top two.

When broken down by mobility device used, the results indicated different preferences for these groups. Those who used walkers, canes and crutches (i.e. those ambulating) showed preference for the PL, followed by the ARISE. Both manual and power wheelchair users had the ARISE as their favourite solution. In the case of manual wheelchair users, the ramp was the second favourite solution, while for power wheelchair and scooter users the ramp and PL were tied as the second favourite solution.

Discussion

The results from this study confirm findings from the literature and provide additional insight into user perspectives of four commonly used HAS: stairs, a ramp, a stair glide and a PL. Further, we were able to get valuable feedback on the usability and functionality of a new ARISE prototype that aims to address some of the limitations of existing solutions. Our findings indicate that while these devices can provide great utility to people with mobility impairments, usability challenges that have a direct impact on user satisfaction could be further improved across all HAS.

While comprehensive studies comparing a range of HAS are lacking in the literature, the importance of these studies should not be diminished. By allowing users to try a number of solutions side by side, it is possible to benchmark these solutions against each other. Further, our study aimed to include users with a broad range of mobility limitations. While much of the previous research has typically focused exclusively on either the needs of seniors or the needs of wheelchair users, getting feedback from a broader group of end users aimed to provide more comprehensive results, as well as provide the opportunity to explore different preferences based on mobility limitations.

Unsurprisingly, stairs were not a viable option for many of our participants. Of those who tried the stairs, a significant proportion was not satisfied with the energy required to use them and reported safety and security concerns, including fear of falling. These findings are well supported in the literature [2,17,19,29]. In particular, the importance of adequate railings is well documented. In a study with older adults, the absence of handrails on ramps and stairs was the most common complaint sited and the presence of handrails was noted as a key determinant that impacted older adults’ choice between navigating stairs or ramps [29]. Also of note, the limitations with the railings brought up by participants in our study support Wolfinbarger’s recommendation that rails be placed on both sides of a ramp or stairway, even though the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) require only that one rail be provided [29].

The stair glide presented challenges for many of our participants. In particular, the need to transfer and the fact that users must leave their mobility device behind limits its functionality for those who depend on wheelchairs and walkers. The time required to use the stair glide was also noted as a limitation; due to the slow drive speed, the need to transfer and the time required to use the seatbelt, the stair glide proved to be the slowest solution in this study. It is also notable that several people remarked that this HAS felt like a device for seniors. The slow speed likely contributed to this perception, but some participants observed that the marketing for this technology is aimed almost exclusively at seniors. This branding may possibly have created a stigma which affected user perspectives of this HAS. Usability limitations of stair glides were also noted, in particular around the seatbelt and foot plates. The literature on the usability of stair glides is sparse, however usability issues with seat belts on HAS have been reported, and the need to provide design alternatives to increase usability has been noted [1].

The ramp was rated as the second favourite solution for both manual and power wheelchair users, with participants noting cost, reliability and durability as significant benefits of this solution. Ratings for “ability to use independently” were also high –comparable with ratings for the ARISE and the PL. The ramp was rated less favourable by those using walkers, canes and crutches, most likely due to the safety and security concerns (e.g. ramp steepness, railings limitations, balance and falling risks) ramps present for ambulators [2,17–19]. While there are obvious advantages of wheeling up a ramp over walking, these different satisfaction ratings may also reflect that the ADAAG standard for ramp design was written to accommodate wheelchair users rather than ambulators [29].

The aesthetics and the large foot print of ramps were also noted as limitations. Other studies confirm that users perceive ramps as a visible symbol of disability and feel they may negatively impact property value [17,19,21,22]. In contrast to these perceptions, however, in a review of the literature, Jung notes that some studies indicate that ramps or lifts not only do not adversely affect the market value of a home, but in some cases can increase a home’s re-saleability [17]. Regardless of the validity of this concern, these perceptions have been reported to have an impact a home owners’ decisions to install ramps, therefore the importance of integrating ramps into the look of the home should not be overlooked. Indeed, Grisbrooke noted that “a successful adaptation tended to fade from sight and become taken for granted” [30].

The PL and ARISE have a number of similarities from an operational standpoint, and it was not surprising to find that these two HAS were rated comparably across a number of characteristics (i.e. ease of learning, ease of use, ability to use independently, physical energy required, durability, reliability and comfort). The PL was rated as the preferred solution for those using walkers, canes and crutches. Participants felt it was easy to use and the capacity to carry items, such as groceries, was considered a big advantage. The literature points to similar advantages of PL, citing convenience and small foot print (i.e. providing a solution in places where ramps are not viable) as the biggest benefits [12,17]. While the cost of PLs is cited as the most significant limitation [12,17], Jung points out that care should be taken when considering economic comparisons of HAS as many of the benefits of HAS are non-economic factors. He further proposes that the cost of a particular intervention is related to its long-term benefits and suggests that people with greater physical limitations or deteriorating mobility could expect more benefits using lifts rather than ramps [17]. Reliability concerns and the need for servicing have also been noted as limitations of this HAS [17].

The ARISE was rated as the favourite solution for manual and power wheelchair users, and the overall preferred solution when results from all participants were considered. Notably, the look of the ARISE solution was rated particularly positively in comparison to other solutions. Participants liked that it addressed inclusivity and felt that it could be well integrated into the look of a house without appearing as a symbol of disability. These results should be considered with some caution however. One issue relates to speed of operation. While many users commented that they liked the speed of the ARISE, it should be noted that the ARISE design enables faster operation times than current regulations allow. A commercially available version of the ARISE would likely have to be slowed to match that of a standard PL, thus negating one of the significant and beneficial features of this novel design. Further, it is anticipated that some of the limitations that have been reported for PLs (e.g. cost, servicing and reliability) would also apply to the ARISE. Interestingly, few participants discussed these concerns during the evaluation. This discrepancy speaks to the challenges one faces when comparing a proof-of-concept prototype with commercially available products. In spite of best efforts to make the ARISE look like a “finished product”, some aspects (e.g. aesthetics of the gates, smoothness of operation and noise) still required further development. When evaluating the ARISE, it is evident that some people made assumptions that the “final” (i.e. commercially available) version would resolve those issues and consequently they did not rate these features negatively (i.e. they provided ratings for the product that they envisioned it would become). Similarly, some participants also had had negative experiences (or had heard negative stories) about the reliability of some of the commercially available solutions; it is possible that their ratings were tainted by these experiences. As participants had no previous experiences (negative or otherwise) with the ARISE, it is possible that they were more likely to rate this solution more positive. It is also apparent that participants were excited by the innovation and “coolness” of this solution, and as a result they may have overlooked some of its limitations, rating some features higher than they might have otherwise. As it is very difficult to overcome these inconsistencies when evaluating a proof-of-concept prototype, we must be somewhat guarded in the interpretation of our results. Nonetheless, results were in general very positive, and have shown that, at the very least, there is appetite for further innovation in this area.

Our findings also indicate that there is no clear “winning solution” that works for everyone. Wolfinbarger notes that even a choice as simple as having stairs versus a ramp is not universal (he recommends entrances should have both ramps and stairs to enable users to use their preferred means of access) [29]. In fact, the ideal solution is most likely unique to the individual, based on their unique functional abilities, housing situation, personal preferences, family support, resources and levels of independence and participation. It is interesting to note that while it is tempting to make presumptions about optimal solutions based on stereotypes, preferences can sometimes be difficult to predict. For example, while we envisioned that the fast, innovative ARISE would be more appealing to younger and more active individuals, this was not always the case. In fact some older people approved of the speed of the ARISE, while some younger people felt it went too fast. The literature underscores the importance of gaining a clear understanding of end user needs and goals, noting that this is critical to successful outcomes and ultimate use of HAS [21].

The results from this study also point to some general HAS concerns that were brought up repeatedly across a number of solutions and need to be highlighted as criteria for future HAS design development. For example, robustness, durability and reliability came up as essential for all HAS (in particular for outdoor solutions), as any failure of a HAS has significant impact on the users’ independence. Also, in some cases, it is the small design details that render a solution inaccessible. Small shifts in the position of operation switches, support bars and railings can make a difference between a user being able to use a solution independently or not. As noted by Heywood:

Failure to get the details right causes much waste because, if you are disabled, the usefulness of a bar can be completely destroyed by its being six inches in the wrong place. The frustration… was all the greater for having been preventable. [21]

Continuous pressure switches were another issue that came up repeatedly. While safety guidelines limit the operation of all accessibility lifts to continuous pressure controls (i.e. the user must press and hold the control button or lever at all times in order to keep the lift in motion), this can pose threats to independence for those with limited hand strength. While the need for safety is paramount, other control options that do not require hand strength should be considered. A final consideration is the care that must be taken around access leading to a HAS (ramping, walkways, direction of door pulls) as it can also impact a user’s ability to use a solution independently. A HAS can be rendered inaccessible if a user is not able to negotiate the small ramp to get on the lift. As user needs vary, keeping solutions adaptable and flexible is one way of maximizing a solutions’ ability to meet a wide range of users and provide the best chances of accommodating changing end user needs.

Study limitations

While several limitations to our study should be noted, perhaps the most pertinent limitation relates to our concerns about participants’ ability to rate HAS features objectively. As an example, we observed some participants struggling to get to the top of the ramp yet still rate that they were “very satisfied” with the effort required. Similarly, one participant was observed struggling with the stair glide (she could not position her foot on the footplate, do up the seatbelt, nor turn the seat to transfer at the top), yet she also provided positive responses for this HAS. Although, participants were asked to be critical of the solutions they were evaluating, the ratings they provided were predominantly positive. Several explanations are proposed. As in all usability studies, there can be a tendency for participants to “want to please” researchers by providing positive responses [31]. It is also possible that pride prevented the participants from wanting to admit (either to the researchers or themselves) that the solution presented challenges for them. Finally, it is plausible that, as with many people with mobility impairments, our participants have become accustomed to the challenges with existing HAS and have learned to lower their expectations of HAS usability over time. For example, our participants may be used to exerting considerable effort every time they use a ramp, so in comparison, the amount of effort required on this one seemed reasonable. This last point has been discussed by Heywood, who noted that people with mobility impairments were so grateful to have had any help at all that they were inclined to understate unsatisfactory solutions. He further notes that while it is common to say that adaptations cannot meet people’s expectations, he found that peoples’ expectations were in general too low rather than too high [21].

Another limitation of our study is that participants focused on the specific HAS design that was being evaluated in the trial, rather than the general category of HAS under evaluation (i.e. they provided feedback on the particular ramp that was being evaluated, rather than ramps in general). While this gave us some very specific information about the details of the particular HAS in the study (e.g. the size of rails, the color of leather, etc.), further directing participants to comment on the general category of HAS may have yielded results with broader application.

Conclusion

By allowing end users to try a range of HAS side by side and having them benchmark one against the other, we were able to outline the individual strengths and limitations of these solutions for a variety of users. This type of research is critical to consumers and prescribers of HAS who need reliable information to make informed decisions about their options in order to make the best use of available funds. This information is also necessary for designers and researchers who need a clear understanding of user needs to drive future development in a meaningful direction.

It is unclear why so little innovation has been done in this area – participants in our study repeatedly commented that existing solutions are lacking and innovation in this area would be desirable. While the ARISE is still an early stage prototype with notable limitations, overall there was widespread enthusiasm for something new. The end user feedback we received at the early stages of our product development has given our group valuable insight into usability and functionality of this new solution, and results are informative for guiding the direction of future development of this solution as well as other initiatives around improving home access.

Implications for Rehabilitation.

It is anticipated that gaining a better understanding of strengths and weaknesses of home access solutions will:

assist clinicians and end users in finding solutions that meet the individuals’ needs.

lead to the development of new or improved solutions that more closely address user needs.

encourage further innovation in the area.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all team members, students and study participants involved in all aspects of this work.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge NSERC Idea to Innovation grant I2IPJ428619, the Rick Hansen Institute Grant 2014-01, Canada Research Chairs, and BCIT’s School of Construction and the Environment Green Values Strategies Fund for their financial support of this project.

References

- 1.Nasarwanji MF, Paquet VL, Feathers DJ, Lenker JA. Usability study of a powered lift for wheelchair users. Proc Hum Fact Ergon Soc Annu Meet. 2008;52:719–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCreadie C, Seale J, Tinker A, Turner-Smith A. Older people and mobility in the home: in search of useful assistive technologies. Br J Occup Ther. 2002;65:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maisel J, Smith E, Steinfield E. Increasing home access: designing for visitability. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwarsson S, Nygren C, Oswald F, et al. Environmental barriers and housing accessibility problems over a one-year period in later life in three European countries. J Hous Elderly. 2006;20:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson K, Lilja M, Petersson I, Borell L. Performance of activities of daily living in a sample of applicants for home modification services. Scand J Occup Ther. 2007;14:44–53. doi: 10.1080/11038120601094997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid D. Accessibility and usability of the physical housing environment of seniors with stroke. Int J Rehabil Res. 2004;27:203–8. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erickson MA, Krout J, Ewen H, Robison J. Should I stay or should I go? Moving plans of older adults. J Hous Elderly. 2006;20:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pynoos J, Nishita CM. The cost and financing of home modifications in the United States. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2003;14:68–73. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey J. Ageing in place: the views of older homeowners on maintenance, renovation and adaptation. Soc Policy J N Z. 2006;27:128–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith SK, Rayer S, Smith EA. Aging and disability: implications for the housing industry and public policy in the United States. J Am Plann Assoc. 2006;74:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scotts M, Saville-Smithe K, James B. International trends in accessible housing for people with disabilities: a selected review of policies and programmes in Europe; North America, United Kingdom, Japan and Australia. 2007 Jan; Report nr Working paper 2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balmer D. Impact of the A18. 1 ASME standard on platform lifts and stairway chairlifts on accessibility and usability. Assist Technol. 2010;22:46–50. doi: 10.1080/10400430903520264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ConvertaStep [Internet] Wolfe Mobility; [last accessed Jun 2014]. Available from: http://wolfemobility.ca/convertastep-c133.php. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Innovative welfare technology [Internet] Liftup; [last accessed Jun 2014]. Available from: http://www.liftup.dk/en/products. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revolutionary vacuum elevator technology [Internet] Vacuum Elevators Canada; [last accessed Jun 2014]. Available from: http://www.vacuumelevators.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Center for Universal Design. Wood ramp design: How to add a ramp that looks good and works too. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung Y, Bridge C, Mills S. Cost-benefit analysis of ramps versus lifts. Sydney: Home Modification Information Clearinghouse, University of New South Wales; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wanklyn P, Kearney M, Hart A, Mulley GP. The provision of ramps for wheelchair users. Clin Rehabil. 1996;10:81–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung Y, Bridge C. Economic dimensions of home modifications: cost-benefit comparisons between ramps and lifts. Proceedings of the International Conference on Best Practices in Universal Design: Festival of International Conferences on Caregiving, Disability, Aging and Technology (FICCDAT); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Accessible housing by design-lifts and residential elevators [Internet] Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation; [last accessed Jun 2014]. Available from: http://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/co/renoho/refash/refash_027.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heywood F. Money well spent: the effectiveness and value of housing adaptations. Bristol, UK: Policy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis B. The stigmatized home: why parents delay removing architectural barriers. Child Environ Quart. 1986;3:63–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattie J, Borisoff J, Leland D, Miller WC. Development of an integrated staircase lift for home access. doi: 10.1177/2055668315594076. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wade DT, Legh-Smith J, Langton Hewer R. Social activities after stroke: measurement and natural history using the Frenchay Activities Index. Int Rehabil Med. 1985;7:176–81. doi: 10.3109/03790798509165991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuling J, de Haan R, Limburg M, Groenier KH. The Frenchay Activities Index: assessment of functional status in stroke patients. Stroke. 1993;24:1173–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.8.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh CP, Jang YM, Yu TB, et al. A Rasch analysis of the Frenchay Activities Index in patients with spinal cord injury. Spine. 2007;32:437–42. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000255095.08523.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Rourke B, Enns H, Borisoff J, et al. Accessibility solutions for outdoor stair use. Poster presented at the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists National Conference; 2013 May 29–Jun 1; Victoria, BC. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang CJ, Michan A, Borisoff J, et al. Client perceptions of home access devices. Poster presented at the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists National Conference; Victoria, BC. May 29–June 1; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfinbarger K, Shehab R. A survey of ramp and stair use among older adults. Proceedings of the IEA 2000/HFES 2000 congress. 2000;4:76–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grisbrooke J. Living with lifts: a study of users’ experiences. Br J Ther Rehabil. 2003;10:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 31.King M, Bruner G. Social desirability bias: a neglected aspect of validity testing. Psych Market. 2000;17:79–103. [Google Scholar]