Abstract

Gastrin is a peptide hormone that is involved in the regulation of sodium balance and blood pressure. Dopamine, which is also involved in the regulation of sodium balance and blood pressure, directly or indirectly interacts with other blood pressure-regulating hormones, including gastrin. This study aimed to determine the mechanisms of the interaction between gastrin and dopamine and tested the hypothesis that gastrin produced in the kidney increases renal dopamine production to keep blood pressure within the normal range. We show that in human and mouse renal proximal tubule cells (hRPTCs and mRPTCs, respectively), gastrin stimulates renal dopamine production by increasing the cellular uptake of l-DOPA via the l-type amino acid transporter (LAT) at the plasma membrane. The uptake of l-DOPA in RPTCs from C57Bl/6J mice is lower than in RPTCs from normotensive humans. l-DOPA uptake in renal cortical slices is also lower in salt-sensitive C57Bl/6J than in salt-resistant BALB/c mice. The deficient renal cortical uptake of l-DOPA in C57Bl/6J mice may be due to decreased LAT-1 activity that is related to its decreased expression at the plasma membrane, relative to BALB/c mice. We also show that renal-selective silencing of Gast by the renal subcapsular injection of Gast siRNA in BALB/c mice decreases renal dopamine production and increases blood pressure. These results highlight the importance of renal gastrin in stimulating renal dopamine production, which may give a new perspective in the prevention and treatment of hypertension.

Keywords: gastrin, dopamine, hypertension, l-DOPA, l-type amino acid transporter

dopamine produced by the kidney plays an important role in the regulation of water and electrolyte balance and blood pressure (3, 4, 9, 20, 47). Endogenous renal dopamine, acting in an autocrine or paracrine manner, inhibits ion transporter/channel/pump activity directly and indirectly, in part, by regulating their protein expression. The physiological effects of dopamine occur by occupation of its specific receptors expressed along the nephron and renal vasculature (3, 4, 9, 20, 47). The renal production of dopamine is dependent on the uptake of the dopamine precursor l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) by renal proximal tubule cells and the activity of l-aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (l-AADC), the enzyme responsible for the conversion of l-DOPA into dopamine in rodents and humans (2, 4, 9, 46, 47). Selective deletion of the gene encoding L-AADC in the mouse renal proximal tubule (RPT) causes hypertension and salt sensitivity (46). l-DOPA is filtered by the glomerulus and is taken up by the RPT. The renal tubular uptake of l-DOPA is an important modulator of renal dopamine synthesis (1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 17, 36, 44, 46). l-DOPA uptake in renal epithelial cells is an active process mediated by amino acid transporters. l-DOPA transporters include the Na+-dependent (B0, B0+ and y+L) and Na+ independent l-amino acid transporters (LAT-1, LAT-2, rBAT, Slc7a12) (2, 5, 17, 28, 36). In renal tubule cells, l-DOPA uptake has been reported to occur through LAT-2 (2, 17, 36). LAT-1 may also be involved; the inhibition of l-DOPA uptake by α2C-adrenoceptors in opossum kidney cells is via LAT-1 (28). The rate-limiting step in renal dopamine synthesis is the uptake of l-DOPA via LAT-1 and LAT-2 (2, 5, 17, 28, 36).

Gastrin, produced by the G-cells of the stomach and duodenum, acting on its receptor, cholecystokinin 2 (CCK2) receptor can increase renal sodium excretion (8, 22, 26, 43). Gastrin is taken up by renal tubules to a greater extent than other gut hormones secreted in response to food intake (26). Gastrin, interacting with dopamine, is involved in the normal regulation of renal sodium handling and blood pressure (8, 22). Indeed, D1-like receptors, e.g., the D1 dopamine receptor, and CCK2 receptor synergistically increase sodium excretion in normotensive but not spontaneously hypertensive rats (8, 22). CCK2 receptor is linked to stimulation of protein kinase C (PKC) (24); PKC and Akt/PKB, contribute to the increase in l-DOPA uptake into RPT cells induced by insulin (6). This study aimed to determine the mechanisms of the interaction between gastrin and dopamine and tested the hypothesis that gastrin synthesized in the kidney increases renal dopamine production to keep blood pressure in the normal range.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cell culture.

RPT cells (RPTCs), isolated from human kidney specimens from patients who had unilateral nephrectomy due to renal carcinoma or trauma, with approval by the pertinent institutional review board (19, 24, 25) were used. Undifferentiated mouse RPTCs (mRPTCs) isolated from C57Bl/6J mice were kindly supplied by Dr. Ulrich Hopfer (Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine). Immortalized RPTCs with low passage numbers (≤18) were used to avoid the confounding effects of cellular senescence. The RPTCs were maintained in DMEM-F-12 (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 IU/ml streptomycin, and 250 μg/ml amphotericin B. The RPTCs were kept at 37°C in an atmosphere 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and cultured to 90–95% confluence, as described (19, 24, 25).

Uptake of l-DOPA in RPTCs and mouse kidney slices.

l-DOPA uptake was assessed by the production of dopamine. The RPTCs were preincubated for 20 min in Krebs buffer in the presence of vehicle or catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor, tolcapone (1 μmol/l; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor pargyline (1 μmol/l) (4) (Sigma-Aldrich). In experiments aimed to evaluate the effect of the CCK2 receptor antagonist (L365,260) (24), which was obtained from Merck, or the LAT inhibitor (2-aminobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid, BCH) (28, 35) (Sigma-Aldrich) on gastrin-stimulated uptake of l-DOPA, the drugs were added to the medium and incubated for 6 min before l-DOPA or l-DOPA plus gastrin treatment. Gastrin17 (cat. no. RP12740-0.5, GenScript, NJ) was added to the medium 5 min before the addition of l-DOPA (100 μM, 15 min). After centrifugation (4°C, 600 g, 3 min) and rapid removal of the uptake solution, the cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold Krebs solution, and recentrifuged (4°C, 600 g, 3 min). The supernatant, to be used for measurement of dopamine, was stored at −20°C until assayed. The results were corrected by the protein concentration of the pelleted cells.

Kidneys were harvested from pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg)-anesthetized mice. The cortex, separated from the medulla, was chopped into small pieces and incubated in DMEM in the presence or absence of the l-amino acid carrier inhibitor 2-aminobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid BCH. BCH (1 mM) was added to the medium and incubated for 6 min before l-DOPA (100 μM) and gastrin (25 or 50 nM) treatment for 20 min. As in the RPTC studies, the supernatant was collected to measure dopamine production (42), using the method described in the manufacturer’s manual (GenWay Biotech, San Diego, CA).

Acute renal-specific downregulation of gastrin.

Gast was selectively silenced in the kidney by the renal subcapsular infusion of Gast-specific siRNA (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, cat. no. SI00191331), via an osmotic minipump (7). The control mice were similarly studied but the renal subcapsular infusate was AllStars negative control (Qiagen, cat. no. 1027280). Adult male BALB/c mice were uninephrectomized 1 wk before the implantation of the minipumps. For the implantation of the minipump, the mice were anesthetized by the intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg body wt). The osmotic minipumps (100 µl; flow rate: 0.5 µl/h for 7 days) were filled with validated Gast-specific siRNA (delivery rate: 3 µg/day) or mock (nonsilencing) siRNA as control. The siRNAs were dissolved in an in vivo transfection reagent (TransIT In Vivo Gene Delivery System, Mirus) under sterile conditions. The minipumps were fitted with a polyethylene delivery tubing (Alzet no. 0007701), and the tip of the tubing was inserted within the subcapsular space of the remaining kidney. Surgical glue was applied at the puncture site to hold the tubing in place and prevent extrarenal leakage. The osmotic pump was sutured to the abdominal wall to prevent excessive movement of the pump for the duration of the study.

Blood pressure measurements.

In both Gast-siRNA and mock (nonsilencing siRNA) infusion groups, blood pressure was measured (Cardiomax II; Columbus Instruments, Columbus OH) from the aorta via the femoral artery under pentobarbital sodium anesthesia (50 mg/kg) before and after the 7-day siRNA infusion (7). Blood pressures were recorded for 1 h after the induction of anesthesia when blood pressures were stable. Telemetric measurement of blood pressure in conscious mice was not performed, because the size and weight of the osmotic minipump needed for siRNA infusion and the radio transmitter needed for telemetry precluded their intraperitoneal and subcutaneous placements. The kidneys were harvested and immunoblotted for gastrin and LAT-1. Thereafter, the mice were euthanized with a bolus intravenous injection of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) (11).

Urine measurements.

Twenty-four urine samples were collected from mice individually housed in metabolic cages. The mice were acclimatized in the metabolic cages for 24 h before the collection of urine. Urinary concentration of dopamine was measured by ELISA, using an antibody specific for murine dopamine (GenWay Biotech). Values were corrected for urine creatinine, measured using a colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

Immunoblotting.

RPTC lysates and renal cortical homogenates were subjected to immunoblotting as described previously (11, 24, 25, 35). The primary antibodies were rabbit monoclonal anti-gastrin (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-LAT-1 (1:500, Abcam), and polyclonal anti-GAPDH (Sigma-Aldrich). The densitometry values were corrected by the expression of GAPDH and shown as percentage of the mean density of the mock (nonsilencing siRNA)-treated group.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was purified using the RNeasy RNA Extraction Mini kit (Qiagen). RNA samples were converted into first-strand cDNA using an RT2 First Strand kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol (SABiosciences-Qiagen). Quantitative gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR (ABI Prism 7900 HT; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The assay used Gast-specific primers (SABiosciences-Qiagen) and SYBR Green real-time PCR detection method, as described in the manufacturer’s manual. The results were analyzed using the ΔCT method.

Immunofluorescence.

Thin sections (3 μm) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded BALB/c mouse kidneys were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated with step-down concentrations of ethanol. Gastrin was visualized using a polyclonal goat anti-gastrin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by Alexa fluor 555-donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Aquaporin 1was visualized using a polyclonal rabbit anti-aquaporin 1 antibody (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), followed by Alexa fluor 488-donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Molecular Probes). For negative control, the primary antibodies were replaced with normal rabbit serum at appropriate dilutions. The immunofluorescence images were acquired using a Zeiss 510 confocal laser scanning microscope. Colocalization of gastrin and aquaporin 1 was identified by a yellow color in the merged images.

Gastrin mRNA expression in mouse kidney, determined by RT-PCR and in situ fluorescence hybridization.

The cortex, outer medulla, inner medulla, and papilla of mouse kidney were carefully separated under a dissecting microscope. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). RNA samples were converted into first-strand cDNA using an RT2 First Strand kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). The gastrin primer sequences were: forward, 5′-ATTCCCCAGCTCTGTGGAC-3′; reverse, 5′-TCGATGGTGAGAGGCTGAG-3′. Amplification conditions for the reactions were: 5 min at 94°C; 40 cycles at 94°C for 50 s, 56°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 1 min; with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Subsequently, 10 μl of PCR product was loaded on a 2% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide and subjected to gel electrophoresis. The gels were photographed under ultraviolet light and stored. β-Actin was used as a cDNA internal control. PCR products were sequenced, and homology was searched using the BLAST algorithm.

In situ RNA hybridization was performed using RNAscope technology (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, thin sections (3 µm) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded mouse kidneys were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated with step-down concentrations of ethanol. The tissues were then treated serially with the following: pretreatment 1 solution (endogenous H2O2 blocker for 10 min); 100°C, 15-min immersion in pretreatment 2 solution); and protease digestion, 40°C for 10 min. The tissues were rinsed with water after each pretreatment step. The tissues were then hybridized with a gastrin RNAscope probe at 40°C for 2 h. After the wash and buffer steps, the signal was amplified using a multistep process. Alkaline phosphatase activity was demonstrated by the application of Red (Fast Red) for 10 min at ambient temperature. The sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin.

Statistical analysis.

The data are expressed as means ± SE. Significant differences between two groups were determined by Student’s t-test. Significant differences among more than two groups were determined by one-way factorial ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effect of gastrin on l-DOPA uptake in RPTCs.

The effect of gastrin on the uptake of l-DOPA in hRPTCs and mRPTCs was determined by the production of dopamine 1,4 and is shown in Fig. 1. In hRPTCs, incubation with 100 μM l-DOPA4 for 15 min resulted in a twofold increase in the production of dopamine (Fig. 1, A and B). Preincubation with gastrin for 5 min, before l-DOPA incubation, stimulated dopamine production in a concentration-dependent manner, with a significant effect observed from 50 to 1,000 nM (Fig. 1A). The addition of 25 nM gastrin did not enhance the uptake of l-DOPA, but increasing the gastrin concentration to 50 nM increased by almost twofold the dopamine production from l-DOPA. Gastrin can regulate sodium transport in kidney via its receptor CCK2 receptor (8, 22, 24, 43). Preincubation of the hRPTCs with the CCK2 receptor antagonist L365,260 (1µM) (24) blunted the increase in dopamine production in the presence of both l-DOPA and gastrin (Fig. 1B), indicating that the increase induced by 50 nM gastrin in l-DOPA uptake was mediated by the CCK2 receptor. To determine the mechanism of the stimulation of the uptake of l-DOPA by gastrin, we studied the effect of BCH (28, 35), an inhibitor of l-type amino acid transporter, on the uptake of l-DOPA. Preincubation of hRPTCs with BCH (1 mM, 6 min) markedly decreased l-DOPA uptake in response to gastrin (50 nM; Fig. 1B). This result shows that the BCH-sensitive, Na+ independent l-type amino acid transporter is involved in the gastrin-stimulated uptake of l-DOPA in hRPTCs.

Fig. 1.

Gastrin stimulates the uptake of l-DOPA in human and mouse renal proximal tubule cells. A: dopamine production in response to incubation (20 min) of varying concentrations of gastrin (1 to 1,000 nM, n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. control, one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test) and l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA; 100 μM); con = control (l-DOPA 100 μM alone). The minimum effective concentration of gastrin was 50 nM. Lines above bar graphs represent SE. B: effect of gastrin, L365,260 (CCK2 receptor inhibitor), and BCH (LAT inhibitor) on uptake of l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) in human renal proximal tubule cells (hRPTCs). hRPTCs (passage 10) were incubated for 15 min at 37°C with vehicle or l-DOPA (100 μM), with or without gastrin (25 or 50 nM, preincubation for 5 min), and found the effective concentration of gastrin (50 nM) we used. For inhibitor studies, hRPTCs were preincubated for 6 min at 37°C with L365,260 (1 µM) or BCH (1 mM) with or without l-DOPA (100 μM) and gastrin (50 nM) treatment; n = 6/group, *P < 0.05 vs. control (first group); #P < 0.05 vs. l-DOPA and gastrin (50 nM) treatment, one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test. C: effect of gastrin, L365,260, and BCH on uptake of l-DOPA) in mouse (C57Bl/6J) renal proximal tubule cells (mRPTCs, passage 18). Treatments for mRPTCs were the same as in Fig. 1B, n = 6/group, *P < 0.05 vs. control (first group); #P < 0.05 vs. l-DOPA and gastrin (50 nM) treatment, one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test. D: total LAT-1 protein was quantified by immunoblotting in hRPTCs and mRPTCs treated with l-DOPA(100 μM) and gastrin (50 nM) with or without BCH (1 mM). Results were corrected for expression of GAPDH protein; n = 6/group. E: plasma membrane LAT-1 protein was quantified by immunoblotting in plasma membranes of hRPTCs and mRPTCs treated with l-DOPA(100 μM) and gastrin (50 nM) with or without BCH (1 mM). Protein concentrations in loaded samples were quantified by BCA assay; n = 6/group, *P < 0.05 vs. others; #P < 0.05 vs. l-DOPA and gastrin treatment; &P < 0.05 vs. hRPTC control group, one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test.

In the absence of gastrin, l-DOPA uptake was similar in mRPTCs from salt-sensitive C57Bl/6J mice11 and hRPTCs (Fig. 1, B and C). In mRPTCs, 50 nM gastrin also stimulated dopamine production, albeit lower than that noted in hRPTCs. Preincubation with the CCK2 receptor antagonist or BCH completely blocked the ability of gastrin to increase in l-DOPA uptake in mRPTCs (Fig. 1C). These results corroborated the results in hRPTCs, that showed that the gastrin-stimulated uptake of l-DOPA is via the CCK2 receptor and BCH-sensitive, Na+ independent l-type amino acid transporter (Fig. 1B). Both mRPTCs and hRPTCs produced low but measurable amounts of dopamine in the absence of l-DOPA (Fig. 1, B and C). This may indicate production of dopamine from l-DOPA sources in the medium as has been reported previously (11). In both cell lines, BCH blunted or prevented the l-DOPA+gastrin (50 nM)-induced increase in dopamine production but did not abolish dopamine production, indicating the presence of other l-DOPA transporters. We then measured LAT-1 expression in hRPTCs and mRPTCs (Fig. 1, D and E). We found that total RPTC LAT-1 expression was not affected by l-DOPA with gastrin with or without preincubation with BCH in both human and mouse RPTCs (Fig. 1D). However, RPTC plasma membrane expression of LAT-1 was increased by l-DOPA and gastrin in hRPTCs and minimally in mRPTCs (Fig. 1E). Preincubation of hRPTCs with BCH that prevented in l-DOPA+gastrin-mediated stimulation of dopamine production (Fig. 1B) also prevented the increase in LAT-1 in the plasma membrane (Fig. 1E). We also found that the abundance of renal plasma membrane LAT-1 is lesser in mRPTCs than in hRPTCs. These data indicate that BCH-sensitive, Na+- independent l-type amino acid transporter plays an important role in the uptake of l-DOPA in hRPTCs but not mRPTCs from salt-sensitive C57Bl/6J mice (11).

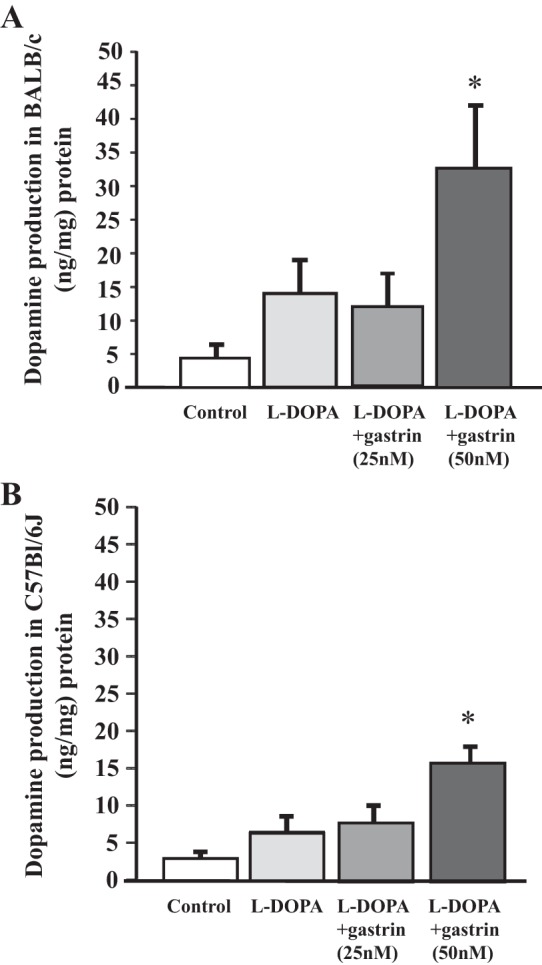

Effect of gastrin on l-DOPA uptake in mouse renal cortical slices.

As shown above, the uptake of l-DOPA is lower in RPTCs from salt-sensitive C57Bl/6J than those from human RPTCs. We have reported that urinary dopamine is lower in C57Bl/6J mice that are salt-sensitive than in SJL mice, which are salt-resistant (11). To determine if there is a mouse strain effect on the renal production of dopamine, we measured l-DOPA uptake in renal cortical slices from C57Bl/6J mice and BALB/c mice, which, like SJL mice (11) are salt resistant (P. A. Jose, unpublished data). Basal levels of dopamine were higher in BALB/c than in C57Bl/6J mice (5.0 ± 1.9 vs. 2.5 ± 0.8, P < 0.05; Fig. 2, A and B). Gastrin increased the uptake of l-DOPA in renal cortical slices from both mouse strains. However, dopamine production was higher in BALB/c than in C57Bl/6J mice. The absolute increase in the renal uptake of l-DOPA induced by gastrin (50 nM) was greater in BALB/c than in C57Bl/6J mice (33 ± 10 vs. 16 ± 2.5, P < 0.05), but the fold increase in l-DOPA uptake was not different between the two mouse strains (6.6- vs. 6.4-fold, P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Gastrin stimulates uptake of l-DOPA in BALB/c and C57Bl/6J mouse kidney cortical slices. A: effect of gastrin on uptake of l-DOPA in renal cortical slices from BALB/c mice. Freshly harvested kidney was separated into cortex and medulla. The renal cortex was chopped into small pieces and incubated in DMEM. Cortical slices were incubated with l-DOPA (100 μM)with or without gastrin (25 and 50 nM); n = 6/group, *P < 0.05 vs. others, one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test. B: effect of gastrin on uptake of l-DOPA in renal cortical slices from C57Bl/6J mice. Preparation and treatment of renal cortical slices were as described in Fig. 2A; n = 6/group, *P < 0.05 vs. others, one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test.

Preincubation of mouse renal cortical slices with the l-type amino acid transporter inhibitor BCH significantly decreased renal dopamine production induced by gastrin (50 nM/20 min) in BALB/c mice (Fig. 3A) but not in C57Bl/6J mice, suggesting that renal cortical l-DOPA transport through the l-type amino acid transporter is decreased in C57Bl/6J mice. This occurred despite the similarity of LAT-1 expression in whole kidney homogenates from both strains; total renal cellular LAT-1 expression was not affected by l-DOPA or gastrin with or without pre-incubation with BCH (Fig. 3B). However, the inability of BCH to inhibit the l-DOPA+gastrin-mediated renal dopamine production in C57Bl/6J mice is in agreement with the inability of l-DOPA+gastrin or BCH to affect LAT-1 membrane expression in RPTCs from C57Bl/6J mice. We next studied the effect of these treatments on the plasma membrane abundance of LAT-1 and found that renal plasma membrane expression of LAT-1 was greater in BALB/c than in C57Bl/6J mice. Preincubation of the renal cortical slices with BCH in the presence of l-DOPA and gastrin that prevented the increase in l-DOPA uptake in BALB/c mice also prevented the increase in LAT-1 in the plasma membrane, similarly to those observed in hRPTCs (Fig. 1, B and C). By contrast, l-DOPA and gastrin, which slightly increased dopamine production in C57Bl/6J mice, did not affect renal plasma membrane LAT-1 abundance; BCH also had no effect on renal plasma membrane LAT-1, the abundance of which was less than that in BALB/c mice (Fig. 3C), effects that recapitulate the mRPTC C57Bl/6J results (Fig. 1, B–E). These data indicate that BCH-sensitive, Na+-independent l-type amino acid transporter plays a primary role in the uptake of l-DOPA in BALB/c (and hRPTCs) but not C57Bl/6J mice.

Fig. 3.

Gastrin stimulates renal cortical uptake of l-DOPA via the l-amino acid transporter. A: effect of BCH (LAT inhibitor) on gastrin-stimulated uptake of l-DOPA in renal cortical slices from BALB/c and C57Bl/6J mice. Renal cortical slices were prepared as described in Fig. 2 and treated as in Fig. 1A, except that only one concentration of gastrin (50 nM) was used; n = 6/group, *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. l-DOPA and gastrin treatment, one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test. B: total LAT-1 protein was quantified by immunoblotting in kidneys of BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice treated with l-DOPA and gastrin with or without BCH as in Fig. 3A.Results were corrected for expression of GAPDH protein. n = 6/group. Lines above the bar graphs represent the standard error from the mean. C. Plasma membrane LAT-1 protein was quantified by immunoblotting in kidneys of BALB/c and C57Bl/6J mice treated with l-DOPA and gastrin with or without BCH as Fig. 3A. Protein concentrations in loaded samples were quantified by BCA assay; n = 6/group, *P < 0.05 vs. others; #P < 0.05 vs. l-DOPA and gastrin treatment; &P < 0.05 vs. BALB/c mice, one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test.

Gastrin expression in the thin descending limb of Henle of mouse kidney.

We found that gastrin is expressed in the thin descending limb (TDL) (Fig. 4). The colocalization of aquaporin 1 (green), a marker of the RPT and TDL12 (Fig. 4, A, E, and I) and gastrin (red) (Fig. 4B, Fig. 4F and Fig. 4J) was evaluated in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded mouse kidney sections using laser confocal microscopy. There was no expression of gastrin in the cortex of the mouse kidney (Fig. 4B); therefore, there was no colocalization of aquaporin 1 and gastrin in the RPT (Fig. 4, C and D). By contrast, there was strong colocalization of gastrin and aquaporin (yellow) in the TDL in both outer (Fig. 4, G and H) and inner (Fig. 4, K and L) medulla of the mouse kidney, indicating that gastrin protein is present in the TDL. Gastrin mRNA was also observed in the renal medulla, using in situ hybridization (Fig. 4M) and RT/PCR (Fig. 4N).

Fig. 4.

Colocalization of gastrin and aquaporin 1 in BALB/c mouse kidney. A–D: gastrin immunofluorescence is absent in the cortex of mouse kidney; aquaporin 1 is expressed in the renal proximal convoluted tubule (PCT). E–H: gastrin and aquaporin 1 colocalize in the thin descending limb (TDL) but not in the proximal straight tubule (PST) or thick ascending limb (TAL) in the outer medulla of mouse kidney. I–L: gastrin and aquaporin 1 colocalize in the TDL in the inner medulla (original magnification, × 400). M: Gast mRNA (arrow), determined by in situ fluorescence hybridization, is present in the TDL. N: Gast mRNA expression in different regions of mouse kidney was determined using specific primers for Gast. The product was identified in the outer medulla, inner medulla, and papilla; no band was seen in the cortex. Mouse stomach mucosa was used as positive control for Gast mRNA. The housekeeping gene β-actin product was detected in all tested samples. Sequencing analysis of RT-PCR products identified mouse Gast mRNA (NM_010257.3). Similar results were obtained in ≥3 separate experiments.

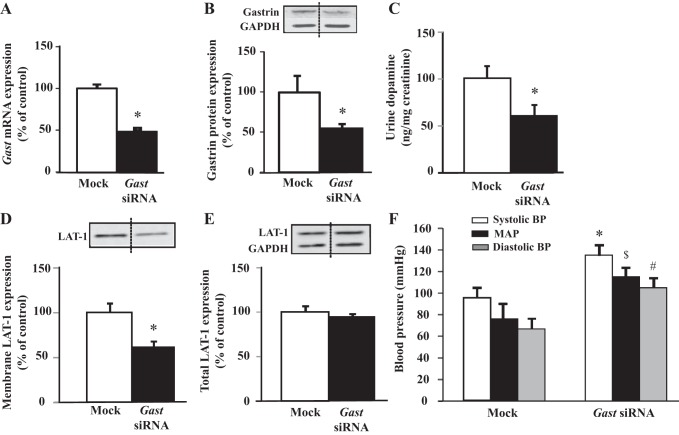

Renal-selective silencing of gastrin decreases urinary dopamine in mice.

To define further the role of renal gastrin in the production of dopamine by the kidney and regulation of blood pressure, we selectively downregulated gastrin expression in the kidney by the renal subcapsular infusion of Gast siRNA in BALB/c mice (Fig. 5). The mRNA (Fig. 5A) and protein (Fig. 5B) expressions of gastrin were decreased by 50% in the kidneys of mice subcapsularly infused with Gast siRNA relative to the kidneys subcapsularly infused with mock, nonsilencing siRNA. The colocalization of gastrin (green) (Fig. 6, A and D) and aquaporin 1 (red) (Fig. 6, B and E) was also evaluated in these kidneys; gastrin expression was significantly decreased in the TDL of mouse kidney subcapsularly infused with Gast siRNA compared with mock, nonsilencing siRNA (Fig. 6, D–F). The renal production of dopamine, assessed by the urinary excretion of dopamine, was decreased by 40% in kidneys treated with Gast siRNA (Fig. 5C), relative to those treated with mock, nonsilencing siRNA, suggesting that renal gastrin is necessary for normal dopamine production. The expression of LAT-1 was also significantly decreased in plasma membrane-enriched fractions from kidneys of mice subcapsularly infused with Gast siRNA (Fig. 5D); no changes were observed in whole kidney homogenates (Fig. 5E), indicating that it is the amount of transporter in the plasma membrane rather than the overall expression of the transporter that mediates the gastrin-stimulated renal l-DOPA uptake.

Fig. 5.

Renal-selective silencing of Gast decreases urinary dopamine and increases blood pressure in BALB/c mice. Gast mRNA was quantified by qRT-PCR in kidneys of BALB/c mice that received a renal subcapsular infusion of Gast-specific (delivery rate: 3 µg/day) or Mock (nonsilencing) siRNA. Results were corrected for expression of Gapdh mRNA; n = 5/group, *P < 0.05 vs. Mock, t-test. GAST protein was quantified by immunoblotting in kidneys of BALB/c mice that received a renal subcapsular infusion of Gast-specific (delivery rate: 3 µg/day) or Mock siRNA. Results were corrected for expression of GAPDH protein; n = 5/group, *P < 0.05 vs. Mock, t-test. C: renal dopamine production was quantified by ELISA in urine of BALB/c mice that received a renal subcapsular infusion of Gast-specific (delivery rate: 3 µg/day) or Mock siRNA; n = 5/group, *P < 0.05 vs. Mock, t-test. D: plasma membrane LAT-1 protein was quantified by immunoblotting in kidneys of BALB/c mice that received a renal subcapsular infusion of Gast-specific(delivery rate: 3 µg/day) or Mock siRNA. Protein concentrations in loaded samples were quantifiedby BCA assay; n = 5/group, *P < 0.05 vs. Mock, t-test. E: total LAT-1 protein was quantified by immunoblotting in kidneys of BALB/c mice that received a renal subcapsular infusion of Gast-specific(delivery rate: 3 µg/day) or Mock (nonsilencing) siRNA. Results were corrected for expression of GAPDH protein; n = 5/group. F: blood pressure was measured from the aorta, via the femoral artery, under pentobarbital sodium anesthesia, in BALB/c mice that received a renal subcapsular infusion of Gast-specific (delivery rate: 3 µg/day) or Mock siRNA; n = 5/group, *P < 0.05 vs. Mock systolic blood pressure; $P < 0.05 vs. Mock mean arterial pressure (MAP); #P < 0.05 vs. Mock diastolic blood pressure; one-way factorial ANOVA, Newman-Keuls.

Fig. 6.

Colocalization of gastrin and aquaporin 1 in BALB/c mouse kidney that received a renal subcapsular infusion of Gast-specific or nonsilencing (Mock) siRNA. A–C: gastrin and aquaporin 1 colocalize in the TDL but not in TAL of mouse kidney subcapsularly infused with Mock siRNA. D–F: gastrin immunofluorescence is very weak in the TDL, but aquaporin 1 is well expressed in the TDL of mouse kidney subcapsularly infused with Gast-specific siRNA (Gastrin siRNA). Similar results were obtained in ≥3 separate experiments.

A high-salt diet increased the blood pressure of C57Bl/6J but not SJL mice (11). The increase in blood pressure with the increase in salt intake in C57Bl/6J mice was associated with a lesser increment in urinary sodium and dopamine relative to SJL mice (11). In the present study, the renal production of dopamine was also less in C57Bl/6J than in BALB/c mice (Fig. 3A), which are salt resistant (Z. Yang, unpublished studies). We therefore measured the blood pressure in BALB/c mice treated with renal subcapsular infusion of Gast siRNA. Systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressures were increased in BALB/c mice with renal subcapsular infusion of Gast siRNA relative to the mice with renal subcapsular infusion of mock, nonsilencing siRNA (Fig. 5F). These data indicate that renal gastrin plays a role in the regulation of blood pressure.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that gastrin, via CCK2 receptor, increases renal dopamine production by stimulating the uptake of l-DOPA in mRPTCs, hRPTCs, and mouse renal cortical slices. Moreover, l-DOPA uptake occurs through the l-type amino acid transporter (e.g., LAT-1), the activity of which may be the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of renal dopamine (2, 5, 17, 28, 36). Our results also suggest that gastrin positively regulates the abundance of l-type amino acid transporters (e.g., LAT-1) in the renal plasma membrane to increase the renal tubular uptake of l-DOPA and dopamine synthesis.

Gastrin is a peptide hormone secreted primarily by G cells in response to the ingestion of food. Food also contains significant amounts of sodium (13, 37, 38), which can increase gastrin secretion even in the absence of food (41). We have reported that gastrin may be involved in the regulation of blood pressure and sodium balance in human subjects (21), and there is evidence that the ability of gastrin released into the circulation to decrease renal sodium transport (43) is important in the regulation of blood pressure (8, 22). Our current study indicates that gastrin can be made by the kidneys (TDL) and that, similarly to gastrin made in stomach G cells, renal gastrin also plays an important role in the regulation of blood pressure, since the renal-selective silencing of Gast increases blood pressure in mice. We show that the renal-selective decrease in gastrin expression is associated with a decrease in the renal plasma membrane expression of LAT-1 and urinary excretion of dopamine. Gastrin is taken up by RPTs to a greater extent than other gut hormones (26). The gastrin receptor CCK2 receptor is expressed in specific nephron segments (including the proximal tubule) (8, 10, 21, 24, 25, 43). Our results show that gastrin (50 nM) can stimulate l-DOPA uptake and dopamine synthesis through LAT-1 in renal cortex and RPTCs. The concentration of gastrin in the luminal fluid cannot be measured separately but would be much higher than that measured in the whole kidney, not only because gastrin is taken up by RPTs 100- to 1,000-fold after 5 min (29) and 100-fold after 4-h injection (26), but also because the half-life of gastrin is also less than 10 min (32). Thus, the RPT concentration could be as high as 15–150 ng/g kidney (11–110 nM). Moreover, our studies suggest that gastrin can be produced in the TDL which can affect other parts of the nephron, including the proximal tubule, via the intrarenal circulation. Indeed, we detected more gastrin in the renal medulla than in the cortex, although these measurements were not made after feeding (data not shown). We presume that the gastrin produced in the stomach is important in natriuresis after a meal and that the gastrin produced in the kidney may participate in basal sodium excretion.

Gastrin, through the CCK2 receptor, can inhibit Na+K+-ATPase activity (25). In hRPTCs, gastrin, through CCK2 receptor, inhibits NHE3 and Na+K+-ATPase activity via the PI3K/PKC pathway (24, 25), and PKC can stimulate the renal uptake of l-DOPA (6). By contrast, α2C-adrenoceptors coupled to pertussis-sensitive G protein decrease cAMP production and PKC activity and decrease l-DOPA uptake (28). Thus, gastrin may negatively regulate renal sodium transport not only by acting on CCK2 receptor to decrease sodium transport by direct effects on renal NHE3 and Na+K+-ATPase activity but also by increasing the renal tubular uptake of l-DOPA and the production of dopamine. The CCK2 receptor and D1-like receptors also synergistically inhibit renal sodium transport, which helps keep the blood pressure in the normal range (8, 22).

The present study shows that the renal tubular uptake of l-DOPA is deficient in C57Bl/6J mice relative to BALB/c mice. In both mRPTCs and renal cortical slices from C57B6L/J mice that are salt sensitive (11, 23, 27, 40), the rate of production of dopamine is decreased compared with hRPTCs and kidney slices from salt-resistant BALB/c mice (P. A. Jose, unpublished observations). The gastrin-stimulated uptake of l-DOPA is also deficient in C57Bl/6J mice. We have reported that the salt sensitivity of C57Bl/6J mice is in part the result of decreased renal dopamine production and defective D1-like receptor function (11). Our current study demonstrates that deficient renal tubular uptake of l-DOPA may be the underlying cause of the decreased renal dopamine production in these salt-sensitive mice and is in agreement with results obtained in rats and salt-sensitive human subjects, indicating that deficient uptake of l-DOPA may cause salt sensitivity (14, 15).

The l-type amino acid transporter (LAT-1 and LAT-2) and Na+-dependent amino acid transporters are responsible for the renal tubular uptake of l-DOPA (2, 5, 17, 28, 36). We found that the gastrin-stimulated renal l-DOPA uptake in BALB/c mice is sensitive to BCH (28, 35), which supports the concept that the uptake of l-DOPA in RPTCs is mainly via the l-type amino acid transporter in these mice. l-Type amino acid transporters include LAT-1 and LAT-2 (17, 36). About 25% of renal l-DOPA uptake occurs through LAT-2, 50% through LAT-1, and the remaining 25% through Na+-dependent transport systems in RPT cells from the spontaneously hypertensive rat (34). LAT-2 has been suggested to play a more important role than LAT-1 in transepithelial amino acid transport (17, 36), but it has a lower affinity for amino acids than LAT-1 (28, 39, 45). Indeed, LAT-1 plays a more relevant role and is more abundant in the vasculature (LAT-1 is widely expressed in nonepithelial cells such as brain, spleen, thymus, testis, skin, liver, placenta, skeletal muscle, and stomach) (31). In opossum kidney cells, l-DOPA uptake could occur through LAT-1 (16). Our data show that, in mouse renal cortex, plasma membrane but not total cellular LAT-1 expression is significantly increased by gastrin. Basal plasma membrane LAT-1 expression in C57Bl/6J mice, which is lower than in BALB/c mice, is not significantly increased by gastrin. Therefore, the deficient uptake of l-DOPA in C57Bl/6J mice may be caused by a deficiency of LAT-1 in the plasma membrane in the basal and gastrin-stimulated states. It should be stated, however, that decreased plasma membrane expression of LAT-1 cannot explain the increased renal sodium transport and hypertension related to the defective renal dopamine function in the spontaneously hypertensive rat (33). Renal LAT-1 and LAT-2 are actually overexpressed and the renal tubular uptake of l-DOPA is increased in spontaneously hypertensive rats before the onset of hypertension (33). Instead, in the spontaneously hypertensive rat, there is a renal resistance to the natriuretic effect of dopamine because of impaired dopamine receptor (D1R and D3R) function (2, 3, 8, 9, 20, 47) and aberrant CCK2 receptor and D1-like receptor interaction (8, 22).

In conclusion, gastrin, via the CCK2 receptor, stimulates RPTC uptake of l-DOPA, resulting in increased dopamine synthesis. The gastrin-stimulated l-DOPA uptake may be via the stimulation of LAT-1 in the plasma membrane. The RPT uptake of l-DOPA is deficient in salt-sensitive C57Bl/6J mice relative to salt-resistant BALB/c mice. Decreasing gastrin expression selectively in the kidney decreases urinary dopamine and increases blood pressure in BALB/c mice. These results highlight the importance of gastrin in stimulating renal dopamine production, which may give us a new perspective in the prevention and treatment of hypertension.

GRANTS

These studies were supported, in part, by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81370358, 81400317) and the US National Institutes of Health (HL-074940, DK-039308, to P. A. Jose).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.J., Y.Z., Y.Y., J.Y., and W.C. performed experiments; X.J., Y.Z., Y.Y., J.Y., W.C., I.A., and P.A.J. analyzed data; X.J. interpreted results of experiments; X.J. and Y.Z. prepared figures; X.J., L.D.A., and I.A. drafted manuscript; X.J., L.D.A., R.A.F., I.A., P.A.J., and Z.Y. edited and revised manuscript; X.J., I.A., P.A.J., and Z.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armando I, Nowicki S, Aguirre J, Barontini M. A decreased tubular uptake of dopa results in defective renal dopamine production in aged rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 268: F1087–F1092, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armando I, Villar VA, Jose PA. Dopamine and renal function and blood pressure regulation. Compr Physiol 1: 1075–1117, 2011. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banday AA, Lokhandwala MF. Dopamine receptors and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 10: 268–275, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carranza A, Nowicki S, Barontini M, Armando I. L-Dopa uptake and dopamine production in proximal tubular cells are regulated by β(2)-adrenergic receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F77–F83, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carranza A, Karabatas L, Barontini M, Armando I. Decreased tubular uptake of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Horm Res 55: 282–287, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carranza A, Musolino PL, Villar M, Nowicki S. Signaling cascade of insulin-induced stimulation of L-dopa uptake in renal proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C1602–C1609, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00090.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuevas S, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Escano C, Asico L, Jones JE, Armando I, Jose PA. Role of renal DJ-1 in the pathogenesis of hypertension associated with increased reactive oxygen species production. Hypertension 59: 446–452, 2012. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.185744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Asico LD, Zheng S, Villar VA, He D, Zhou L, Zeng C, Jose PA. Gastrin and D1 dopamine receptor interact to induce natriuresis and diuresis. Hypertension 62: 927–933, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi MR, Kouyoumdzian NM, Rukavina Mikusic NL, Kravetz MC, Rosón MI, Rodríguez Fermepin M, Fernández BE. Renal dopaminergic system: Pathophysiological implications and clinical perspectives. World J Nephrol 4: 196–212, 2015. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v4.i2.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Weerth A, Jonas L, Schade R, Schöneberg T, Wolf G, Pace A, Kirchhoff F, Schulz M, Heinig T, Greten H, von Schrenck T. Gastrin/cholecystokinin type B receptors in the kidney: molecular, pharmacological, functional characterization, and localization. Eur J Clin Invest 28: 592–601, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escano CS, Armando I, Wang X, Asico LD, Pascua A, Yang Y, Wang Z, Lau YS, Jose PA. Renal dopaminergic defect in C57Bl/6J mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R1660–R1669, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00147.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gimmon Z, Murphy RF, Chen MH, Nachbauer CA, Fischer JE, Joffe SN. The effect of parenteral and enteral nutrition on portal and systemic immunoreactivities of gastrin, glucagon and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP). Ann Surg 196: 571–575, 1982. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198211000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill JR Jr, Grossman E, Goldstein DS. High urinary dopa and low urinary dopamine-to-dopa ratio in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension 18: 614–621, 1991. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.18.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman E, Hoffman A, Tamrat M, Armando I, Keiser HR, Goldstein DS. Endogenous dopa and dopamine responses to dietary salt loading in salt-sensitive rats. J Hypertens 9: 259–263, 1991. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes P, Serräo MP, Viera-Coelho MA, Soares-da-Silva P. Opossum kidney cells take up L-DOPA through an organic cation potential-dependent and proton-independent transporter. Cell Biol Int 21: 249–255, 1997. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1997.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes P, Soares-da-Silva P. Na+-independent transporters, LAT-2 and b0,+, exchange L-DOPA with neutral and basic amino acids in two clonal renal cell lines. J Membr Biol 186: 63–80, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gildea JJ, McGrath HE, Van Sciver RE, Wang DB, Felder RA. Isolation, growth, and characterization of human renal epithelial cells using traditional and 3D methods. Methods Mol Biol 945: 329–345, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-125-7_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horita S, Seki G, Yamada H, Suzuki M, Koike K, Fujita T. Roles of renal proximal tubule transport in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rev 9: 148–155, 2013. doi: 10.2174/15734021113099990009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang X, Wang W, Ning B, Liu X, Gong J, Gan F, Gao X, Zhang L, Jose PA, Qin C, Yang Z. Basal and postprandial serum levels of gastrin in normotensive and hypertensive adults. Clin Exp Hypertens 35: 74–78, 2013. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2012.690474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang X, Chen W, Liu X, Wang Z, Liu Y, Felder RA, Gildea JJ, Jose PA, Qin C, Yang Z. The synergistic roles of cholecystokinin B and dopamine D5 receptors on the regulation of renal sodium excretion. PLoS One 11: e0146641, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leonard AM, Chafe LL, Montani JP, Van Vliet BN. Increased salt-sensitivity in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-knockout mice. Am J Hypertens 19: 1264–1269, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu T, Jose PA. Gastrin induces sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3 phosphorylation and mTOR activation via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-/protein kinase C-dependent but AKT-independent pathway in renal proximal tubule cells derived from a normotensive male human. Endocrinology 154: 865–875, 2013. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu T, Konkalmatt PR, Yang Y, Jose PA. Gastrin decreases Na+,K+-ATPase activity via a PI 3-kinase- and PKC-dependent pathway in human renal proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 310: E565–E571, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00360.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melis M, Krenning EP, Bernard BF, de Visser M, Rolleman E, de Jong M. Renal uptake and retention of radiolabeled somatostatin, bombesin, neurotensin, minigastrin and CCK analogues: species and gender differences. Nucl Med Biol 34: 633–641, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuire JJ, Van Vliet BN, Halfyard SJ. Blood pressures, heart rate and locomotor activity during salt loading and angiotensin II infusion in protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) knockout mice. BMC Physiol 8: 20–24, 2008. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-8-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moura E, Silva E, Serrão MP, Afonso J, Kozmus CE, Vieira-Coelho MA. α2C-Adrenoceptors modulate L-DOPA uptake in opossum kidney cells and in the mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F928–F938, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00217.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melicharova L, Laznickova A, Laznicek M. Preclinical evaluation of gastrin derivatives labelled with 111In: radiolabelling, affinity profile and pharmacokinetics in rats. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 158: 544–551, 2014. doi: 10.5507/bp.2013.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prasad PD, Wang H, Huang W, Kekuda R, Rajan DP, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Human LAT1, a subunit of system L amino acid transporter: molecular cloning and transport function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 255: 283–288, 1999. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palnaes Hansen C, Stadil F, Rehfeld JF. Metabolism and acid secretory effect of sulfated and nonsulfated gastrin-6 in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: G903–G909, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinho MJ, Gomes P, Serrão MP, Bonifácio MJ, Soares-da-Silva P. Organ-specific overexpression of renal LAT2 and enhanced tubular L-DOPA uptake precede the onset of hypertension. Hypertension 42: 613–618, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000091822.00166.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinho MJ, Serrão MP, Gomes P, Hopfer U, Jose PA, Soares-da-Silva P. Over-expression of renal LAT1 and LAT2 and enhanced L-DOPA uptake in SHR immortalized renal proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int 66: 216–226, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinho MJ, Serrão MP, Jose PA, Soares-da-Silva P. Overexpression of non-functional LAT1/4F2hc in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells from the spontaneous hypertensive rat. Cell Physiol Biochem 20: 535–548, 2007. doi: 10.1159/000107537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinto V, Pinho MJ, Soares-da-Silva P. Renal amino acid transport systems and essential hypertension. FASEB J 27: 2927–2938, 2013. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-224998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehfeld JF, Friis-Hansen L, Goetze JP, Hansen TV. The biology of cholecystokinin and gastrin peptides. Curr Top Med Chem 7: 1154–1165, 2007. doi: 10.2174/156802607780960483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schick RR, Schusdziarra V, Schröder B, Classen M. Effect of intraduodenal or intragastric nutrient infusion on food intake in man. Z Gastroenterol 29: 637–641, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segawa H, Fukasawa Y, Miyamoto K, Takeda E, Endou H, Kanai Y. Identification and functional characterization of a Na+-independent neutral amino acid transporter with broad substrate selectivity. J Biol Chem 274: 19745–19751, 1999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugiyama F, Churchill GA, Higgins DC, Johns C, Makaritsis KP, Gavras H, Paigen B. Concordance of murine quantitative trait loci for salt-induced hypertension with rat and human loci. Genomics 71: 70–77, 2001. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Survé VV, Håkanson R. Evidence that peroral calcium does not activate the gastrin-ECL-cell axis in the rat. Regul Pept 73: 177–182, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0167-0115(98)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sampaio LF, Mesquita FP, de Sousa PR, Silva JL, Alves CN. The melatonin analog 5-MCA-NAT increases endogenous dopamine levels by binding NRH:quinone reductase enzyme in the developing chick retina. Int J Dev Neurosci 38: 119–126, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Schrenck T, Ahrens M, de Weerth A, Bobrowski C, Wolf G, Jonas L, Jocks T, Schulz M, Bläker M, Neumaier M, Stahl RA. CCKB/gastrin receptors mediate changes in sodium and potassium absorption in the isolated perfused rat kidney. Kidney Int 58: 995–1003, 2000. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolfovitz E, Grossman E, Folio CJ, Keiser HR, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Derivation of urinary dopamine from plasma dihydroxyphenylalanine in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 84: 549–557, 1993. doi: 10.1042/cs0840549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner CA, Lang F, Bröer S. Function and structure of heterodimeric amino acid transporters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1077–C1093, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang MZ, Yao B, Wang S, Fan X, Wu G, Yang H, Yin H, Yang S, Harris RC. Intrarenal dopamine deficiency leads to hypertension and decreased longevity in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 2845–2854, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI57324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang MZ, Harris RC. Antihypertensive mechanisms of intra-renal dopamine. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 24: 117–122, 2015. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]