Abstract

It has been hypothesized that apically expressed L-type Ca2+ channel Cav1.3 (encoded by CACNA1D gene) contributes toward an alternative TRPV6-independent route of intestinal epithelial Ca2+ absorption, especially during digestion when high luminal concentration of Ca2+ and other nutrients limit TRPV6 contribution. We and others have implicated altered expression and activity of key mediators of intestinal and renal Ca2+ (re)absorption as contributors to negative systemic Ca2+ balance and bone loss in intestinal inflammation. Here, we investigated the effects of experimental colitis and related inflammatory mediators on colonic Cav1.3 expression. We confirmed Cav1.3 expression within the segments of the mouse and human gastrointestinal tract. Consistent with available microarray data (GEO database) from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, mouse colonic expression of Cav1.3 was significantly reduced in trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) colitis. In vitro, IFNγ most potently reduced Cav1.3 expression. We reproduced these findings in vivo with wild-type and Stat1−/− mice injected with IFNγ. The observed effect in Stat1−/− suggested a noncanonical transcriptional repression or a posttranscriptional mechanism. In support of the latter, we observed no effect on the cloned Cav1.3 gene promoter activity and accelerated Cav1.3 mRNA decay rate in IFNγ-treated HCT116 cells. While the relative contribution of Cav1.3 to intestinal Ca2+ absorption and its value as a therapeutic target remain to be established, we postulate that Cav1.3 downregulation in IBD may contribute to the negative systemic Ca2+ balance, to increased bone resorption, and to reduced bone mineral density in IBD patients.

Keywords: calcium absorption, calcium channel, inflammation, interferon, intestine

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is one of the chronic gastrointestinal disorders associated with osteopenia and osteoporosis. The relative risk of developing bone fractures in patients with IBD is 40% higher than in the general population, and the reported prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis among IBD patients ranges from 22 to 77% and 17 to 41%, respectively (6, 29). The pathogenesis of osteopenia/osteoporosis in IBD is complex and multifactorial and includes malnutrition, malabsorption, low body mass index, use of corticosteroids, smoking, increasing age, and the type of IBD (Crohn's disease vs. ulcerative colitis) (15, 22). One of the possible mechanisms contributing to bone loss in IBD is impaired mineral homeostasis either from decreased intestinal absorption and/or low renal reabsorption of calcium, thus creating a negative Ca2+ balance. In support of this, Huybers et al. (18) demonstrated that in a mouse model of Crohn’s-like ileitis (TNFΔARE mice), both duodenal and renal Ca2+ absorptive epithelia displayed a significant downregulation of the key Ca2+ transport protein genes: TRPV6 (transient receptor potential vanilloid 6), calbindin-D9K, and PMCA1b (ATP2B1, ATPase plasma membrane Ca2+ transporting 1) in the gut, and calbindin-D28K, and NCX1 (SLC8A1, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger) in the kidney. These changes were accompanied with reduced trabecular and cortical bone thickness and volume in TNFΔARE mice (18). Furthermore, we showed that in several models of experimental colitis both tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interferon-γ (IFNγ) reduce the expression and activity of Klotho in the renal distal convoluted tubules, where it normally supports renal Ca2+ reabsorption by stabilizing the transient receptor potential vanilloid 5 (TRPV5) channel on the apical membrane of distal tubule epithelial cells (31, 33). In the distal convoluted tubules, the impaired apical Ca2+ transport was accompanied by decreased activity of the basolateral NCX1 Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, which was transcriptionally inhibited by IFNγ via a Stat1-dependent mechanism (30), collectively leading to increased urinary calcium wasting (31).

In the gut, Ca2+ absorption is fairly complex and involves both transcellular pathway involving apical TRPV6, cytosolic calbindin-D9K, and basolateral Pmca1b Ca2+ pump, as well as a less dynamically regulated paracellular route (9). More recently, another player was postulated to contribute to the intestinal Ca2+ absorption, Cav1.3 (CACNA1D), an apical L-type channel (19). Outside the gut, this channel is expressed in cochlea inner hair cells and enterochromaffin cells, where it aids in hearing and catecholamine secretion, respectively. Interestingly, inhibition of Cav1.3 channels may play a protective role against neurodegeneration in dopaminergic neurons such as in Parkinson disease. Although little is known about its function in the intestine, it is known to be expressed and active in both human and rodent gastrointestinal tracts. In contrast to other channels such as TRPV6 that work under a hyperpolarized setting, Cav1.3 is hypothesized to contribute to an alternative, TRPV6-independent, route of intestinal Ca2+ absorption. TRPV6 plays a more dominant role under the polarizing conditions between meals, whereas Cav1.3 plays a dominant role under postprandial depolarizing conditions, such as during digestion, when nutrients and luminal Ca2+ are abundant (19). Interestingly, a review of microarray data of colonic gene expression in IBD patients deposited in GEO database (11) indicated relatively consistent downregulation of Cav1.3 mRNA expression; one of the best-designed studies with sigmoid colon biopsies of ulcerative colitis patients and their healthy twins showed decreased Cav1.3 mRNA expression in seven of ten monozygotic twins with ulcerative colitis compared with their discordant siblings (21).

In this study, we investigated the segmental differences in Cav1.3 expression in the murine and human gut and the effects of colitis and associated inflammatory mediators on the expression of colonic Cav1.3. We found that epithelial expression of Cav1.3 is significantly reduced in the epithelial cells in the inflamed colon and that IFNγ is a key mediator in the posttranscriptional downregulation of this channel in both in vivo and in vitro models of inflammation. We propose that the concomitant reduction in the expression of major intestinal and renal Ca2+ channels and transporters, including Cav1.3, likely contributes to the negative systemic Ca2+ balance and increased bone resorption associated with IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and experimental colitis.

Wild-type and Stat1−/− mice on 129S6/SvEv background were purchased from Taconic Farms (Hudson, NY). TNBS colitis was induced in 10- to 12-wk-old mice by intracolonic single dose administration of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS, Sigma Aldrich) (2.5 mg/mouse dissolved in 50% ethanol). Control mice received equivalent volume of PBS enema. All mice were euthanized 5 days later. The TNBS model was selected based on our previously published changes in bone metabolism and density and systemic Ca2+ homeostasis (30, 31, 35). Body weight changes were monitored daily after the induction of colitis. Colonic inflammation was assessed based on histological changes as well as levels of proinflammatory cytokine expression in the distal colon. Wild-type (WT) or Stat1-deficient mice were injected with PBS or recombinant mIFNγ (50,000 units/mouse ip; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) daily for 3 days. On the fourth day, colons were harvested for Cav1.3 mRNA and protein analysis by qPCR and Western blotting, respectively. Colonic segments were collected, flushed with PBS, and opened longitudinally on nitrocellulose membrane. For histological evaluation, tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific) and embedded in paraffin. Samples were cut into 5-µm-thick sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The animal use protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cav1.3 tissue expression profiling by real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from the mouse kidney (whole), duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and proximal and distal colon (mucosal scrapings) using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen//ThermoFisher, Carlsbad, CA). We reverse-transcribed 250 ng of total RNA using the cDNA synthesis qScript (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA) or Transcriptor Universal cDNA Master kit (Roche). qPCR reactions for Cav1.3 mRNA as well as endogenous reference gene (TATA box binding protein, TBP) were set up using commercially available TaqMan primers (Applied Biosystems/ThermoFisher; Grand Island, NY), PerfeCTa qPCR Super Mix (Quanta Biosciences), and cDNA (10% of the real-time reaction). Data were analyzed and expressed as a relative fold change of the gene expression, normalized to TBP gene and relative to normalized Cq value (cycle at which the curvature of the amplification curve is maximal) obtained from the kidney (2−ΔΔCt) as indicated. TissueScan Human Major Tissue qPCR Arrays (HMRT102) were purchased from OriGene (Rockville, MD). HMRT102 contains prenormalized cDNA from 48 human tissues. Two duplicate plates were analyzed: one with manufacturer-provided GAPDH primers using PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences), the second with a commercial TaqMan primer/probe set obtained from Applied Biosystems. Data were processed in a manner consistent with mouse Cav1.3 mRNA and were normalized to renal Cav1.3 expression.

Immunofluorescence.

Colonic sections were harvested and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific). Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm-thick tissue sections. After deparaffinization and rehydration, antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in citrate buffer (10 mm sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0). After washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the slides were blocked for 1 h in 10% normal chicken serum in PBS containing Tween 20 (0.1%) (PBST). Next, sections were incubated with primary mouse monoclonal antibody directed against Cav1.3α1 pore-forming subunit (NeuroMab clone N38/8, 1:100 dilution, UC Davis/NIH NeuroMab Facility, Davis, CA) in PBST containing 3% BSA, overnight at 4°C. After three washes in PBST, the slides were incubated with the chicken anti-goat conjugated with AlexaFluor-647(6 μg/ml in PBST, Invitrogen). After three washes with PBST, slides were mounted with a drop of mounting medium with DAPI (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies). The slides were visualized under the microscope (EVOS FL Auto, Life Technologies). NeuroMab clone N38/8 is a well-validated monoclonal antibody against Cav1.3α1 that showed no signal in the retina of Cav1.3α1−/− mice and clear single band in WT mice (38), ~50% reduced signal in the cardiomyocytes of Cav1.3α1+/− mice (16) and loss of immunoreactivity for Cav1.3α1 by immunostaining and Western blotting in patients with somatic mutations in Cav1.3α1-encoding CACNA1D gene in the adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas (2).

Cells and treatment.

HCT116, human colonic adenocarcinoma was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA; ATCC CCL-247). Cells were cultured in McCoy's 5a Modified Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (50 U/ml of penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin; GIBCO/ThermoFisher). Cells were treated for 24 h with control medium or media supplemented with IFNγ (100 U/ml), IL1β (2 ng/ml) and TNFα (10 ng/ml) individually or in combination (cytomix; all from Peprotech). To inhibit de novo transcription, cells were treated with actinomycin D (ActD; Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) or with an equivalent volume of DMSO.

Western blotting.

Mucosal scrapings of PBS or IFNγ-treated mice were homogenized in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktails and sonicated to shear DNA. The cleared lysates were mixed 1:1 with Laemmli sample buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol, separated by gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (TGX gels, Bio-Rad; 30 μg/lane), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5% wt/vol dry milk powder (Bio-Rad). The was followed by incubation with one of the following antibodies: anti-Cav1.3α1 NeuroMab clone N38/8 or anti-GAPDH mouse monoclonal antibody (MA5-15738, Pierce) in 2.5% blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. They were then washed with TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling) at room temperature for 1 h and developed using Super Signal West Pico HRP substrate (Pierce). Images were acquired using G:Box gel doc system (Syngene; Cambridge, UK).

Cloning of the murine Cav1.3 via gene promoter, transfection, and reporter assays.

The sequence of the murine CACNA1D gene promoter relative to its predicted transcription start site was obtained from the Eukaryotic Promoter Database (EPD) of experimentally validated promoters for selected model organisms developed and maintained by the Swiss Institute for Bioinformatics (10). Transcription start site was identified in position −481 relative to the start codon based (reference sequence NM_001083616.2). C57BL/6 mouse genomic DNA was used to amplify four fragments of the promoter region with 5′ ends at −1,183 nt (forward primer GCGGTACCCCTCTTTGAGCAAGGAGCAC, KpnI adapter underlined), −1,139 nt (GCGGTACCAATTCACGCTGAGCCTTTTG), −498 nt (GCGGTACCCTCCCCCAGGTGTGAGAGT), and the reverse primer at position +362 nt relative to the transcription start site, and −138 nt upstream of the start codon (GCCTCGAGCGCTTCAGCAGGGGGTGG, XhoI adapter underlined). The first two constructs varied primarily by the absence of a putative Stat1 binding site (TTCCCAGAAACAT) at position −1,162/−1,150 nt. All reporter constructs were created in pGL3-basic vector with Firefly luciferase as a reporter (Promega, Madison, WI) and sequenced on both strands to confirm fidelity. Promoterless pRL-null with Renilla luciferase (Promega) was cotransfected into HCT116 cells as an internal control. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were treated with recombinant human IFNγ (100 U/ml) for another 24 h. Relative luciferase activity assay was performed with Dual Luciferase kit (Promega) and tube luminometer (FB12; Zylux, Maryville, TN).

RESULTS

Expression of Cav1.3 in the mouse and human gastrointestinal tract.

RNA was isolated from the naive mouse kidneys or whole-thickness intestinal segments from duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and proximal and distal colon and analyzed for Cav1.3 mRNA expression by qPCR. Cav1.3 transcript was readily detected in all intestinal segments. In the small intestine, we observed a decreasing gradient of expression along the longitudinal axis, with a significant increase in Cav1.3 mRNA expression in the proximal and distal colon (Fig. 1A). qPCR analysis of human cDNA also showed readily detectable Cav1.3 mRNA in all segments analyzed, with the highest expression detected in the sigmoid/rectum (Fig. 1B). Therefore, our data appear contrary to published semiquantitative assessment of Cav1.3α1 expression in the rat by immunofluorescence by Morgan et al. (24), who reported the highest level of expression in the distal jejunum and proximal ileum and very low expression in the colon. Contrary to nuclear labeling reported by Morgan et al. using polyclonal antibody raised against peptide 809–825, expression of Cav1.3α1 pore-forming subunit detected in the colon with a monoclonal antibody was not observed in the nucleus (Fig. 1, A and B). At lower magnification and higher exposure settings, Cav1.3α1 expression was detectable in the surface epithelial and upper crypt cells, along with scattered lamina propria cells (possibly resident immune cells) and in the submucosa (muscularis mucosae or cells of the myenteric plexus) (Fig. 1C). More detailed analysis would be required to identify nonepithelial cells expressing Cav1.3α1 in the colon. At higher magnification and lower exposure settings, apical expression of Cav1.3α1 appeared to be dominant in the colon (Fig. 1D). Cav1.3 expression in the human colon is also supported by immunohistochemical detection data in the Human Protein Atlas (34), as exemplified in Fig. 1E (image credit: Human Protein Atlas; http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000157388-CACNA1D/tissue/colon). CACNA1D data from Human Protein Atlas have been generated with a Prestige Antibody Powered by Atlas Antibodies produced by Sigma (HPA020215) against 136 aa human recombinant protein, most suitable for human detection.

Fig. 1.

Expression of Cav1.3 in the murine and human gastrointestinal tract. qPCR detection of Cav1.3 mRNA expression in different segments of the mouse (normalized to TBP) (A) and human (normalized to GAPDH) (B) gastrointestinal tract. In both species, renal expression was used as a calibrator. C and D: immunofluorescent detection of Cav1.3 in the mouse colon. Red, Cav1.3; blue, nuclei (DAPI). E: Cav1.3 protein expression in the human colon (image credit: Human Protein Atlas (34); cropped image from http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000157388-CACNA1D/tissue/colon).

Decreased colonic epithelial expression of Cav1.3 in experimental colitis.

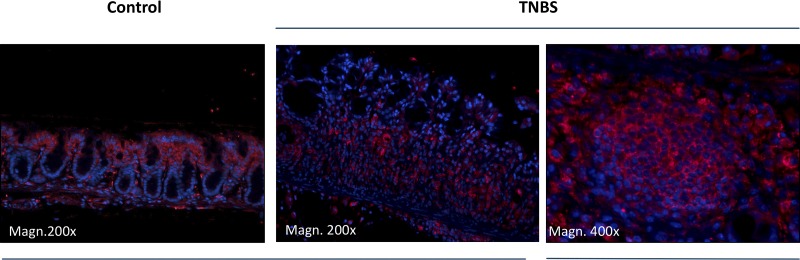

To assess the effects of experimental colitis on the expression of Cav1.3, we induced colitis by intrarectal administration of TNBS in ethanol as described earlier (30, 31). TNBS induced characteristic colitis with significant mucosal immune infiltration, submucosal edema, and focal loss of surface epithelium (Fig. 2A). Expression of Cav1.3α1 analyzed using qPCR from RNA isolated from whole-thickness colonic specimens was significantly reduced by ~50% (Fig. 2B). Immunofluorescence analysis of Cav1.3α1 protein expression in the colonic mucosa showed a dramatic reduction in expression in the epithelial cells, with concomitant increase in fluorescence within the putative immune cells infiltrating the lamina propria and submucosa. (Fig. 3). This increased expression of Cav1.3α1 in nonepithelial compartment may indicate a significantly underestimated difference in Cav1.3 transcript level analyzed in whole-thickness RNA preparations.

Fig. 2.

Mucosal expression of Cav1.3 mRNA in experimental colitis. A: representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of colonic mucosa from control and TNBS-treated mice. B: qPCR detection of Cav1.3 mRNA expression in the colonic mucosa of control and TNBS-treated mice. N = 3 for control, N = 5 for TNBS. *P = 0.02, Student's t-test.

Fig. 3.

Mucosal expression of Cav1.3 protein in experimental colitis. Immunofluorescent detection of Cav1.3 in the mouse colon. Red, Cav1.3; blue, nuclei (DAPI).

IFNγ inhibits colonic epithelial expression of Cav1.3 via and STAT1-independent posttranscriptional mechanism.

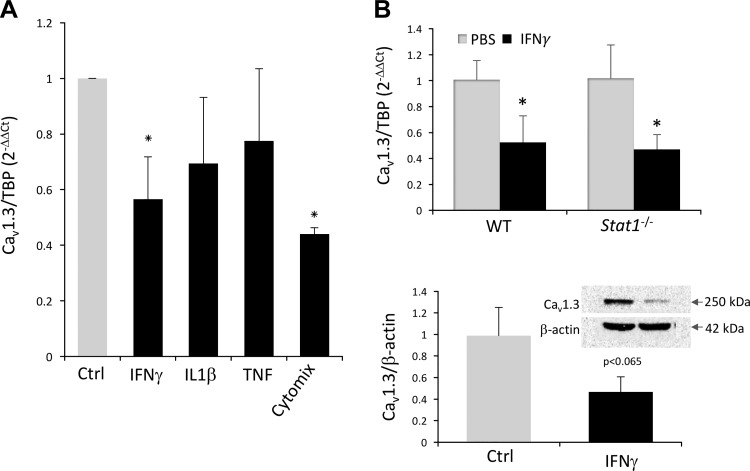

To address the mechanism of reduced expression of Cav1.3 during intestinal inflammation, Cav1.3-expressing HCT116 colonic adenocarcinoma cells were treated with IL1β, IFNγ, and TNFα individually or in combination (cytomix) for 24 h, and Cav1.3 mRNA was analyzed by qPCR. Among the three cytokines tested, IFNγ was the only one that significantly inhibited Cav1.3 mRNA expression (Fig. 4A). No additive or synergistic effects were observed when the three cytokines were used in combination (Fig. 4A). Since the canonical IFNγ signaling is driven by STAT1-dependent modulation of gene transcription, we tested whether this pathway is critical for the observed decrease in Cav1.3 mRNA expression in vivo. To this end, we treated WT and Stat1−/− C57BL/6 mice with recombinant IFNγ by three daily intraperitoneal injections and tested Cav1.3 mRNA and protein expression in the colon by qPCR and Western blotting, respectively. IFNγ induced a decrease in Cav1.3 expression similar that observed in TNBS colitis (Fig. 4B). There was no difference in the response to IFNγ in WT and Stat1-deficient mice, thus suggesting a STAT1-independent mechanism of Cav1.3 inhibition (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on Cav1.3 mRNA and protein expression in vitro and in vivo. A: qPCR analysis of Cav1.3 mRNA expression in HCT116 colonic adenocarcinoma cells treated for 24 h with IFNγ (100 U/ml), IL1β (2 ng/ml), and TNFα (10 ng/ml) individually or in combination (cytomix). Data were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA followed by Fisher PLSD post hoc test. *Differences between respective treatment and control (Ctrl; P < 0.05). B: colonic expression of Cav1.3 mRNA and protein in WT or Stat1−/− mice injected with PBS or IFNγ (50,000 units/mouse ip daily for 3 days). qPCR data normalized to PBS-injected controls for each genotype. *Differences between respective treatment and control (P < 0.05). Western blotting summary with a representative image of Cav1.3 and β-actin expression; P value of Student's t-test indicated.

To further verify whether the effects of IFNγ repress active transcription of Cav1.3 gene, we treated HCT116 cells with ActD to inhibit de novo transcription and with or without of IFNγ for 24 h. In this experimental scenario, IFNγ reduced the steady-state level of Cav1.3 mRNA by ~50% (Fig. 5A), similar to that observed in non-ActD-treated cells (Fig. 4A). Moreover, none of the cloned Cav1.3 gene promoter fragments, spanning the region of −251 nt to −1,553 nt relative to the putative transcription start site, were affected by IFNγ treatment in HCT116 cells transiently transfected with the respective reporter construct (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Posttranscriptional mechanism of reduced Cav1.3 mRNA expression in HCT116 cells treated with IFNγ. A: HCT116 cells were treated with ActD to inhibit de novo transcription and treated with 100 U/ml of IFNγ for 24 h. *Differences between IFNγ and control (P < 0.05). B: 4 deletion constructs of the cloned murine Cav1.3 gene promoter in Firefly luciferase (Luc) reporter vector pGL-basic (Promega), or promoterless vector, were cotransfected with Renilla luciferase vector pRL-null into HCT116 cells and treated with control medium or with 100 U/ml of IFNγ for 24 h. All tested promoter constructs were functional, but no significant effects of IFNγ were detected.

Since all the performed experiments suggested a posttranscriptional regulation of Cav1.3 mRNA expression by IFNγ, we tested Cav1.3 transcript stability/decay over time in ActD-treated HCT116 cells treated with PBS (control) or IFNγ over a period of 24 h. qPCR analysis of Cav1.3 and GAPDH (internal control) indicated that IFNγ led to faster Cav1.3 transcript decay (Fig. 6), suggesting that the mechanism responsible for the reduced expression of Cav1.3 by IFNγ in vitro, and likely during experimental colitis in vivo, involves transcript degradation and not reduced gene transcription.

Fig. 6.

IFNγ accelerates Cav1.3 mRNA decay in colonic epithelial cells. HCT116 cells were treated with ActD to inhibit de novo gene transcription in control or IFNγ-supplemented medium (100 U/ml). Cells were harvested at 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h into treatment and expression of Cav1.3 mRNA was analyzed by qPCR. qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH transcript, with time “zero” as the calibrator. A t-test at individual time points was used for statistical analysis. *Differences between IFNγ and control (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The concept of negative systemic calcium balance as a contributor to metabolic changes in the bone and to a decreased bone mineral density in IBD is based in decreased Ca2+ intake (dairy avoidance and vitamin D insufficiency) and inhibition of epithelial Ca2+ transport in the intestine and kidneys (15). In this scenario, homeostatic mechanisms geared toward maintenance of steady circulating Ca2+ levels may lead to an increased skeletal Ca2+ resorption at the expense of bone mineral density. Combined deficits in intestinal and renal Ca2+ transport and the direct effects of inflammatory mediators on bone metabolism are likely the key contributors to osteopenia and osteoporosis of chronic inflammation.

The relative contributions of transcellular and paracellular pathways to total Ca2+ absorption are somewhat controversial and are subject to modulation by the amount and concentration of luminal ionized Ca2+, which depend on Ca2+ intake, bioavailability from complex foods, e.g., dietary fibers, local solubility and luminal pH, or transit time in a particular segment. The conventional view is that ~85% of total intestinal Ca2+ transport occurs in jejunum and ileum through a weakly regulated paracellular route driven by high luminal Ca2+ concentrations through tight junctions, and linear within the range of 5–200 mM Ca2+. Active intestinal Ca2+ transport is thought to occur predominantly in duodenum and proximal jejunum. This highly regulated and vitamin D3-sensitive transcellular transport occurs via combined actions of apical TRPV6 channel, cytosolic buffer and Ca2+ shuttle calbindin D9K, and basolateral PMCA1b calcium pump and is predominant at low luminal Ca2+ concentrations (up to ~5 mM). When dietary Ca2+ is restricted in between meals (semistarvation), the intestine becomes more polarized. Such circumstances favor TRPV6, with maximal opening for Ca2+ at −60 and −150 mV (19). More recently, it has been proposed that TRPV6 and an L-type Cav1.3 Ca2+ channel may have complementary roles in Ca2+ entry into the intestinal epithelial cell (19). In this scenario, Cav1.3 plays a dominant role under depolarizing conditions observed during digestion (maximum opening for Ca2+ at −20 to −10 mV), mainly when luminal nutrients and Ca2+ are abundant (9, 19).

While reliable human studies on intestinal Ca2+ absorption in IBD are lacking, in a mouse model of Crohn’s-like ileitis (TNFα-overexpressing TNFΔARE mice), duodenal Ca2+ absorptive epithelia displayed significant downregulation of TRPV6, calbindin D9K, and PMCA1b calcium pump (18). These alterations were accompanied by increased bone resorption, as shown by reduced trabecular and cortical bone thickness and volume and by increased total deoxypyridinoline in the serum of TNFΔARE mice (18). The same report also showed that key components of renal Ca2+ reabsorption, calbindin D28K and basolateral Na+/Ca2+ exchanger NCX1, were also reduced (18). Our group has further dissected the effects of experimental colitis on the renal Ca2+ handling. We showed that increased urinary Ca2+ wasting is mediated by TNFα- and IFNγ-dependent inhibition of Klotho, which led to hypersialylation of apical TRPV5 Ca2+ channel, cytokine-induced TRPV5 endocytosis, its UBR4-dependent ubiquitination, and proteasomal degradation (31, 33). We also described the mechanism responsible for the reduced expression and activity of NCX1 exchanger responsible for basolateral exit of Ca2+ in the renal epithelial cells (30).

The effects of intestinal inflammation on intestinal epithelial Cav1.3 expression have not been investigated despite its postulated importance in the net dietary Ca2+ absorption (19). Also, the expression of Cav1.3 channel in the murine and human gut has not been systematically studied. Our qPCR analysis of Cav1.3 mRNA expression along the mouse and human intestinal tract indicated that, although the transcript is readily detectable in all segments, its highest expression is in the distal segments, proximal and distal colon in mouse, and sigmoid/rectum in human samples. Colonic Cav1.3 expression has also been demonstrated in rats, where it was elevated in a model of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel disease (37). We further demonstrated that experimental colitis is associated with decreased expression of Cav1.3 mRNA and protein in the epithelial cells, and provided evidence that IFNγ may be the key cytokine that induces posttranscriptional loss of Cav1.3 transcript stability. Interestingly, in the colon, reduced epithelial Cav1.3 expression was accompanied with higher expression of the channel in the infiltrating immune cells. The identity of the cells highly expressing Cav1.3 in the inflamed mucosa is not clear at this point. It also remains unclear what is the mechanisms that alters Cav1.3 mRNA stability in epithelial cells while allowing its continuous expression in the mucosal immune cells, which presumable are similarly exposed to IFNγ in situ in mucosal inflammation. Both murine and human Cav1.3 mRNA have a highly conserved binding site for miR-3064-5p microRNA. Also, while Cav1.3 mRNA appears to have to canonical AU-rich elements in its 3′ end, it has a uniquely high number (21 in the entire transcript) of the GAIT elements (gamma interferon activated inhibitor of ceruloplasmin mRNA translation), which contribute to translational inhibition (25). While GAIT complex formation may contribute to reduced Cav1.3 protein level in the intestinal epithelial cells, it has not been conclusively linked to mRNA stability; thus the precise mechanism of reduced Cav1.3 mRNA remains to be elucidated.

Historically, colon has not been considered as a significant contributor to the total Ca2+ absorption. However, the colonic and ileal sojourn time are very similar (in rats 184 and 187 min, respectively) (7), and colonic expression of TRPV6, calbindin D9K, and PMCA1b has been described (1, 14, 17, 32, 36). Dependence of calcium absorption in the colon on vitamin D3 has also been shown (12, 13, 20, 28). Interestingly, during vitamin D deficiency, prevalent in IBD patients (8), net Ca2+ absorption was higher in the rodent proximal or distal colon than in the jejunum or ileum (12). In Caco-2 colonocytes, Cav1.3 calcium channel was exclusively required for prolactin-stimulated calcium transport (26). With this fragmentary information, the precise impact of Cav1.3 activity on net intestinal Ca2+ absorption remains to be fully established. However, it is conceivable that reduced Cav1.3 expression during chronic colitis contributes to total losses of dietary and systemic Ca2+ resulting from reduced expression and activity of other intestinal and renal epithelial Ca2+ transporters. The totality of these phenomena may explain the largely negative results of clinical trials with calcium supplementation in pediatric IBD patients and adult IBD patients treated with corticosteroids (3, 5) and may explain the reported lack of correlation between calcium intake and bone density status in premenopausal women with IBD (4). Moreover, decreased expression of Cav1.3 may have other unforeseen consequences for the function of colonocytes. It has been recently described in cardiomyocytes, that the COOH terminus of Cav1.3 translocates to the nucleus where it functions as a transcriptional regulator (23). One of its targets is the myosin II regulatory light chain protein, required to maintain the stability of myosin II and cellular integrity and involved in regulating cell adhesion, migration, and division (27, 37). It remains to be elucidated whether similar transcriptional effects of Cav1.3 occur in the intestinal epithelial cells.

GRANTS

This research was funded by NIH/NIDDK 4R37DK033209 (to F. K. Ghishan).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.M.R., P.R.K., and F.K.G. conceived and designed research; V.M.R., M.M.G., and N.A.P. performed experiments; V.M.R., M.M.G., and N.A.P. analyzed data; V.M.R. and P.R.K. interpreted results of experiments; V.M.R. and P.R.K. prepared figures; M.M.G. and P.R.K. drafted manuscript; M.M.G., P.R.K., and F.K.G. approved final version of manuscript; P.R.K. edited and revised manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armbrecht HJ, Boltz MA, Bruns ME. Effect of age and dietary calcium on intestinal calbindin D-9k expression in the rat. Arch Biochem Biophys 420: 194–200, 2003. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azizan EA, Poulsen H, Tuluc P, Zhou J, Clausen MV, Lieb A, Maniero C, Garg S, Bochukova EG, Zhao W, Shaikh LH, Brighton CA, Teo AE, Davenport AP, Dekkers T, Tops B, Küsters B, Ceral J, Yeo GS, Neogi SG, McFarlane I, Rosenfeld N, Marass F, Hadfield J, Margas W, Chaggar K, Solar M, Deinum J, Dolphin AC, Farooqi IS, Striessnig J, Nissen P, Brown MJ. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and CACNA1D underlie a common subtype of adrenal hypertension. Nat Genet 45: 1055–1060, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ng.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benchimol EI, Ward LM, Gallagher JC, Rauch F, Barrowman N, Warren J, Beedle S, Mack DR. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone mineral density in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 45: 538–545, 2007. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3180dca0cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein CN, Bector S, Leslie WD. Lack of relationship of calcium and vitamin D intake to bone mineral density in premenopausal women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 98: 2468–2473, 2003. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein CN, Seeger LL, Anton PA, Artinian L, Geffrey S, Goodman W, Belin TR, Shanahan F. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of calcium supplementation for decreased bone density in corticosteroid-using patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 10: 777–786, 1996. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.63205000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjarnason I, Macpherson A, Mackintosh C, Buxton-Thomas M, Forgacs I, Moniz C. Reduced bone density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 40: 228–233, 1997. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.2.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronner F. Mechanisms of intestinal calcium absorption. J Cell Biochem 88: 387–393, 2003. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Pinto R, Pietropaoli D, Chandar AK, Ferri C, Cominelli F. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and vitamin D deficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 21: 2708–2717, 2015. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz de Barboza G, Guizzardi S, Tolosa de Talamoni N. Molecular aspects of intestinal calcium absorption. World J Gastroenterol 21: 7142–7154, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreos R, Ambrosini G, Périer RC, Bucher P. The Eukaryotic Promoter Database: expansion of EPDnew and new promoter analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 43, D1: D92–D96, 2015. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 207–210, 2002. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Favus MJ. Factors that influence absorption and secretion of calcium in the small intestine and colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 248: G147–G157, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Favus MJ, Kathpalia SC, Coe FL, Mond AE. Effects of diet calcium and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on colon calcium active transport. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 238: G75–G78, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman TC, Howard A, Bentsen BS, Legon S, Walters JR. Cellular and regional expression of transcripts of the plasma membrane calcium pump PMCA1 in rabbit intestine. Am J Physiol 269: G126–G131, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghishan FK, Kiela PR. Advances in the understanding of mineral and bone metabolism in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G191–G201, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00496.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goonasekera SA, Hammer K, Auger-Messier M, Bodi I, Chen X, Zhang H, Reiken S, Elrod JW, Correll RN, York AJ, Sargent MA, Hofmann F, Moosmang S, Marks AR, Houser SR, Bers DM, Molkentin JD. Decreased cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel activity induces hypertrophy and heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest 122: 280–290, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI58227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoenderop JG, Hartog A, Stuiver M, Doucet A, Willems PH, Bindels RJ. Localization of the epithelial Ca2+ channel in rabbit kidney and intestine. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1171–1178, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huybers S, Apostolaki M, van der Eerden BC, Kollias G, Naber TH, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Murine TNF(ΔARE) Crohn’s disease model displays diminished expression of intestinal Ca2+ transporters. Inflamm Bowel Dis 14: 803–811, 2008. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellett GL. Alternative perspective on intestinal calcium absorption: proposed complementary actions of Ca(v)1.3 and TRPV6. Nutr Rev 69: 347–370, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee DB, Walling MM, Levine BS, Gafter U, Silis V, Hodsman A, Coburn JW. Intestinal and metabolic effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in normal adult rat. Am J Physiol 240: G90–G96, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lepage P, Häsler R, Spehlmann ME, Rehman A, Zvirbliene A, Begun A, Ott S, Kupcinskas L, Doré J, Raedler A, Schreiber S. Twin study indicates loss of interaction between microbiota and mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 141: 227–236, 2011. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lima CA, Lyra AC, Rocha R, Santana GO. Risk factors for osteoporosis in inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 6: 210–218, 2015. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v6.i4.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu L, Sirish P, Zhang Z, Woltz RL, Li N, Timofeyev V, Knowlton AA, Zhang XD, Yamoah EN, Chiamvimonvat N. Regulation of gene transcription by voltage-gated L-type calcium channel, Cav1.3. J Biol Chem 290: 4663–4676, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.586883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan EL, Mace OJ, Helliwell PA, Affleck J, Kellett GL. A role for Ca(v)1.3 in rat intestinal calcium absorption. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 312: 487–493, 2003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukhopadhyay R, Jia J, Arif A, Ray PS, Fox PL. The GAIT system: a gatekeeper of inflammatory gene expression. Trends Biochem Sci 34: 324–331, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakkrasae LI, Thongon N, Thongbunchoo J, Krishnamra N, Charoenphandhu N. Transepithelial calcium transport in prolactin-exposed intestine-like Caco-2 monolayer after combinatorial knockdown of TRPV5, TRPV6 and Ca(v)1.3. J Physiol Sci 60: 9–17, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park I, Han C, Jin S, Lee B, Choi H, Kwon JT, Kim D, Kim J, Lifirsu E, Park WJ, Park ZY, Kim DH, Cho C. Myosin regulatory light chains are required to maintain the stability of myosin II and cellular integrity. Biochem J 434: 171–180, 2011. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petith MM, Wilson HD, Schedl HP. Vitamin D dependence of in vivo calcium transport and mucosal calcium binding protein in rat large intestine. Gastroenterology 76: 99–104, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollak RD, Karmeli F, Eliakim R, Ackerman Z, Tabb K, Rachmilewitz D. Femoral neck osteopenia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 93: 1483–1490, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.468_q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radhakrishnan VM, Kojs P, Ramalingam R, Midura-Kiela MT, Angeli P, Kiela PR, Ghishan FK. Experimental colitis is associated with transcriptional inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoform 1 (NCX1) expression by interferon γ in the renal distal convoluted tubules. J Biol Chem 290: 8964–8974, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.616516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radhakrishnan VM, Ramalingam R, Larmonier CB, Thurston RD, Laubitz D, Midura-Kiela MT, McFadden RM, Kuro-O M, Kiela PR, Ghishan FK. Post-translational loss of renal TRPV5 calcium channel expression, Ca2+ wasting, and bone loss in experimental colitis. Gastroenterology 145: 613–624, 2013. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomasset M, Parkes CO, Cuisinier-Gleizes P. Rat calcium-binding proteins: distribution, development, and vitamin D dependence. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 243: E483–E488, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thurston RD, Larmonier CB, Majewski PM, Ramalingam R, Midura-Kiela M, Laubitz D, Vandewalle A, Besselsen DG, Muhlbauer M, Jobin C, Kiela PR, Ghishan FK. Tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma down-regulate Klotho in mice with colitis. Gastroenterology 138: 1384–1394.e1–2, 2010. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347: 1260419, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uno JK, Kolek OI, Hines ER, Xu H, Timmermann BN, Kiela PR, Ghishan FK. The role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in down-regulation of osteoblast Phex gene expression in experimental murine colitis. Gastroenterology 131: 497–509, 2006. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W, Na T, Wu G, Jing H, Peng JB. Down-regulation of intestinal apical calcium entry channel TRPV6 by ubiquitin E3 ligase Nedd4-2. J Biol Chem 285: 36586–36596, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu J, Luo HS, Chen L, Zhou T. [Altered expression of L-type calcium channel alpha1C and alpha1D subunits in colon of rats with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 89: 2713–2717, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou J, Lee A, Yang J. The expression of whirlin and Cav1.3α1 is mutually independent in photoreceptors. Vision Res 75: 53–59, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]