We investigated myocardial effects of acute application of progesterone. In females, but not males, progesterone attenuates and slows cardiomyocyte contraction with no effect on calcium transients. Progesterone also reduces myofilament calcium sensitivity in female hearts. This may adversely affect heart function, especially when serum progesterone levels are high in pregnancy.

Keywords: sex hormones, sex differences, gender, excitation-contraction coupling

Abstract

Acute application of progesterone attenuates cardiac contraction, although the underlying mechanisms are unclear. We investigated whether progesterone modified contraction in isolated ventricular myocytes and identified the Ca2+ handling mechanisms involved in female C57BL/6 mice (6–9 mo; sodium pentobarbital anesthesia). Cells were field-stimulated (4 Hz; 37°C) and exposed to progesterone (0.001–10.0 μM) or vehicle (35 min). Ca2+ transients (fura-2) and cell shortening were recorded simultaneously. Maximal concentrations of progesterone inhibited peak contraction by 71.4% (IC50 = 160 ± 50 nM; n = 12) and slowed relaxation by 75.4%. By contrast, progesterone had no effect on amplitudes or time courses of underlying Ca2+ transients. Progesterone (1 µM) also abbreviated action potential duration. When the duration of depolarization was controlled by voltage-clamp, progesterone attenuated contraction and slowed relaxation but did not affect Ca2+ currents, Ca2+ transients, sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) content, or fractional release of SR Ca2+. Actomyosin MgATPase activity was assayed in myofilaments from hearts perfused with progesterone (1 μM) or vehicle (35 min). While maximal responses to Ca2+ were not affected by progesterone, myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was reduced (EC50 = 0.94 ± 0.01 µM for control, n = 7 vs. 1.13 ± 0.05 μM for progesterone, n = 6; P < 0.05) and progesterone increased phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C. The effects on contraction were inhibited by lonaprisan (progesterone receptor antagonist) and levosimendan (Ca2+ sensitizer). Unlike results in females, progesterone had no effect on contraction or myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in age-matched male mice. These data indicate that progesterone reduces myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in female hearts, which may exacerbate manifestations of cardiovascular disease late in pregnancy when progesterone levels are high.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We investigated myocardial effects of acute application of progesterone. In females, but not males, progesterone attenuates and slows cardiomyocyte contraction with no effect on calcium transients. Progesterone also reduces myofilament calcium sensitivity in female hearts. This may adversely affect heart function, especially when serum progesterone levels are high in pregnancy.

Listen to this article’s corresponding podcast at https://ajpheart.podbean.com/e/acute-progesterone-modifies-cardiac-contraction/.

cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of hospitalization and death for men and women (55). Even so, there are male-female differences in incidence, prevalence, presentation, and outcomes associated with cardiovascular diseases (22, 26, 55, 63). Sex differences in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases may originate, in part, from differences in normal heart function. Women have higher resting heart rates and longer corrected QT intervals than men (10, 28, 67). They also have a higher ejection fraction at rest, although men respond to exercise with a greater increase in ejection fraction (9, 28, 43). Interestingly, there also are sex differences in cardiac contractile function in animal models, with most studies reporting larger, faster contractions in males compared with females (49). These findings have fueled interest in links between sex steroid hormones and cardiac contraction, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood (2, 46, 49).

Receptors for the three primary classes of sex hormones (estrogen, testosterone, and progesterone) have been identified on cardiomyocytes (23, 27, 38, 41, 44, 45). This suggests that the effects of sex hormones on myocardial contractility are due, at least in part, to actions on the myocytes themselves. Traditionally, the effects of sex steroid hormones on the heart have been attributed to genomic actions, mediated by binding to nuclear receptors that alter gene expression (7, 35). However, these hormones also act via rapid, nongenomic mechanisms (59, 64). Although the nongenomic effects of estrogen and testosterone on the heart have been investigated in a number of studies (2, 49), much less is known about the acute effects of progesterone on the heart.

Progesterone levels fluctuate between 2.5 nM in the follicular phase and 40.6 nM in the luteal phase in pre-menopausal women (30). However, peak progesterone rises during pregnancy to 160–318 nM in the second trimester and 300–1,200 nM in the third trimester (24) with similar levels (e.g. 186 nM) reported in mid-pregnancy in the mouse (14, 15). Preclinical studies have shown that acute exposure to physiological levels of progesterone (100–1000 nM) reduces action potential duration (APD) and attenuates peak contraction in ventricular muscle (42, 56, but cf. 68). The effect on APD has been attributed to an increase in slow delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs), which may prolong the QT interval and contribute to arrhythmias when progesterone levels are high (47). By contrast, the mechanism or mechanisms responsible for acute effects of progesterone on contraction have not been identified. This is important, as the negative inotropic effects of progesterone may contribute to, or exacerbate, cardiovascular complications of pregnancy including heart failure (25).

Cardiac contraction occurs when Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels triggers Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which binds to the myofilaments to initiate contraction (8). In theory, progesterone could act at one or more sites involved in Ca2+ homeostasis or at the myofilaments to attenuate cardiac contraction, although this has not been investigated. The objectives of this study were to determine whether acute application of progesterone affected contractions and Ca2+ homeostasis in isolated ventricular myocytes and to investigate the mechanisms involved. Field-stimulation and electrophysiology studies were conducted in myocytes from adult female C57BL/6 mice acutely exposed to progesterone or vehicle control. Myofilament actomyosin MgATPase activity and myofilament phosphorylation assays used myofilament proteins isolated from adult female hearts perfused with either progesterone or vehicle control. Some experiments also used myocytes and hearts from age- and strain-matched male mice.

METHODS

Animals and ethical approval.

Experiments followed the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals (CCAC, Ottawa, ON, Canada: vol. 1, 2nd ed., 1993; vol. 2, 1984). Experimental protocols were approved by the Dalhousie University Committee on Laboratory Animals. Female and C57BL/6 mice (6–9 mo of age) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constant, QC, Canada) and housed in groups of five in microisolator cages located in the Carleton Animal Care Facility. Some experiments also used male mice of the same age and strain. Female mice were used without respect to their estrous stage. All mice were exposed to a 12-h light/dark cycle, and food and water were provided to mice ad libitum.

Myocyte isolation.

Ventricular myocytes were isolated by enzymatic dissociation as previously described (20). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg ip) coinjected with heparin (3,000 U/kg). The heart was perfused at 37°C (10 min) with oxygenated Ca2+-free isolation solution of the following composition (mM): 105 NaCl, 25 HEPES, 20 glucose, 5 KCl, 3 Na-pyruvate, 1 MgCl2, 1 lactic acid, and 0.33 NaH2PO4 (pH 7.4, NaOH). The heart was then perfused for ~10 min with Ca2+-free isolation solution supplemented with collagenase type II (8.0 mg/30 ml; Worthington), dispase II (3.0 mg/30 ml; Roche Diagnostics), trypsin (0.5 mg/30 ml; Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada), and 50 µM CaCl2. Following perfusion, the ventricles were minced in a high-potassium solution containing the following (in mM): 50 l-glutamic acid, 45 KCl, 30 KH2PO4, 20 taurine, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 3 MgSO4, and 0.5 EGTA (pH to 7.4, KOH). Cells were filtered through a 225-µM polyethylene mesh.

Experimental protocols.

Field-stimulation, current-clamp, and voltage-clamp experiments were performed with established techniques (19, 37). Briefly, myocytes were incubated with fura-2 AM (5 µM; 20 min; room temperature) in the dark in a chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE200; Nikon). Cells were superfused at a rate of 3 ml/min at 37°C with the following buffer (in mM): 135.5 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.4 with NaOH). In voltage-clamp experiments, 4-aminopyridine (4 mM) and lidocaine (0.3 mM) were added to the buffer to block transient outward K+ and Na+ currents, respectively.

Cell shortening and Ca2+ transients were recorded simultaneously by splitting the microscope light between a video camera (Philips, Markham, ON, Canada) and a photomultiplier tube (Photon Technologies, Birmingham, NJ) with a dichroic cube (Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT). A video-edge detector was used to measure cell length (120 samples/s). A DeltaRam fluorescence system (Photon Technologies International) was used to excite cells at 340 and 380 nm. Fluorescence emitted at 510 nm was recorded for both wavelengths (200 samples/s) with Felix software (Photon Technologies International). The background fluorescence was subtracted from each excitation wavelength and the ratio of emission at 340 and 380 nm was converted to Ca2+ concentration with an in vitro calibration curve as we have described in detail previously (58).

In field-stimulation studies, cells were stimulated at 4 Hz with bipolar pulses delivered with platinum electrodes via a stimulus isolation unit (SIU-102; Warner, Hamden, CT) controlled by pClamp 8.2 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Cumulative concentration-response curves were generated for progesterone concentrations from 0.001 to 10.0 µM. Progesterone stock solution was dissolved in DMSO; the highest concentration used (e.g., 0.03%) was included in all solutions and used as a vehicle control. Thirty-second recordings were made at 7-min intervals for control and progesterone-treated cells for a total exposure time of 35 min. We found that responses to progesterone stabilized within 2–4 min (Fig. 1). Electrophysiological recordings were made with microelectrodes (15–25 MΩ; 2.7 M KCl) and an Axoclamp 2B amplifier controlled by pClamp software. Cells were superfused with buffer supplemented with either vehicle control or 1 µM progesterone for 30–35 min before recording. In discontinuous single electrode voltage-clamp studies (5–8 kHz), cells were paced with trains of ten 50-ms conditioning pulses from −80 to 0 mV (4 Hz), repolarized to −40 mV, and depolarized to 0 mV with a 200-ms test step designed to simultaneously elicit ICa-L and Ca2+ transients and contractions. Some experiments were repeated at a frequency of 2 Hz. Capacitance was determined with pClamp software by integrating capacitive transients elicited by test steps from −60 to −50 mV. SR Ca2+ content was assessed after the conditioning pulse train by application of caffeine (10 mM) with a rapid solution switcher designed to maintain temperature at 37°C. Caffeine was applied for 1 s in nominally Ca2+-free buffer of the following composition (in mM): 140 LiCl, 10 caffeine, 10 glucose, 5 HEPES, 4 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 4 4-aminopyridine, and 0.3 lidocaine (32). In current-clamp studies, trains of ten 3-ms pulses were used to pace myocytes (4 Hz). Current-clamp and voltage-clamp experiments were performed in cells superfused with either vehicle control or progesterone as indicated. In some experiments, the progesterone receptor (PR) antagonists mifepristone (10 µM; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI; 47) or lonaprisan (1 µM; AdooQ Bioscience, Irvine, CA; 21) were used. The Ca2+ sensitizer, levosimendan (1 µM; 11), was also used in some studies. Stock solutions for all drugs were made in DMSO (final concentration 0.1%) and the vehicle alone was used as a control in all experiments.

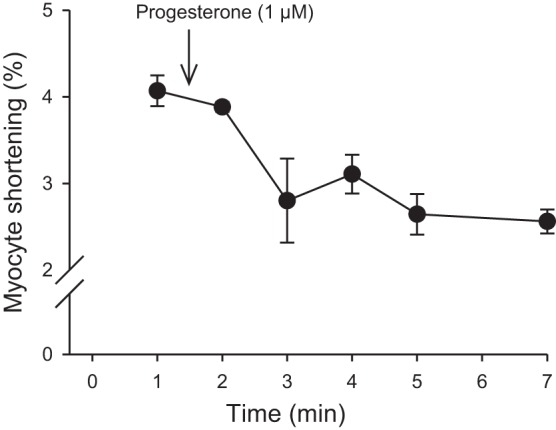

Fig. 1.

Acute application of progesterone rapidly inhibited contractions in ventricular myocytes from female mice. Cells were paced at 4 Hz and superfused with buffer for 5–10 min to stabilize before application of drug. Control recordings are shown at the 1 min time point and 1 µM progesterone was applied as indicated. Peak contractions decreased rapidly after application of drug and responses stabilized within 2–4 min. Values represent means ± SE; n = 3 myocytes from 3 female mice.

Myofilament isolation.

Myofilaments were isolated as previously described (39, 66). Hearts were perfused (3 ml/min; 37°C) with buffer composed of the following (in mM): 135.5 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.4 with NaOH) supplemented with either vehicle control or 1 µM progesterone for 35 min. The ventricles were removed, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use. Ventricles were homogenized in ice-cold buffer composed of the following (in mM): 60 KCl, 30 imidazole (pH 7.0), 2 MgCl2, 0.01 leupeptin, 0.1 PMSF, 0.2 benzamidine, and phosphatase inhibitors (P0044; Sigma-Aldrich). After centrifugation (14,000 g; 15 min; 4°C) the pellet was resuspended in buffer supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 (45 min, on ice). This solution was centrifuged at 1,100 g for 15 min at 4°C and the pellets were washed three times in ice-cold buffer. Myofilaments were frozen for molecular analysis or kept on ice and used immediately for actomyosin Mg2+-ATPase assays.

Actomyosin MgATPase activity.

Actomyosin Mg2+-ATPase activity was assessed as previously described (39, 66). Briefly, myofilaments (25 µg) were incubated in ATPase buffers with increasing concentrations of free Ca2+ (10 min; 32°C). Free Ca2+ was calculated as described previously (50). The reaction was quenched with 10% tricholoacetic acid. Inorganic phosphate production was measured by adding equal volumes of 0.5% FeSO4 and 0.5% ammonium molybdate in 0.5 M H2SO4 and reading the absorbance at 630 nm.

Myofilament protein phosphorylation.

Myofilament proteins (10 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE (12%) and fixed in 50% methanol-10% acetic acid (23°C) overnight. Phosphorylation of myosin-binding protein C, desmin, troponin T, tropomyosin, troponin I, and myosin-light chain 2 was assessed with ProQ Diamond staining (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Imaging was performed with a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and data were analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Gels were stained with Coomassie to assess protein loading; myosin was used as a loading control.

Data analysis.

Field stimulation and electrophysiology data were analyzed with Clampfit 8.2 (Molecular Devices). Statistical tests were performed with Sigma Plot 12.0 (Systat Software) and graphs were created with the same software. Contractions and Ca2+ transients were averaged (50 responses for each) in field stimulation experiments. Cell shortening was the difference between resting cell length and peak contraction. The rates of shortening and lengthening represent the average rate for each parameter. Ca2+ transients were the difference between diastolic and systolic Ca2+. All data are presented as mean ± SE. Data were analyzed with t-tests, one-way ANOVA or two-way repeated measures ANOVA. Multiple comparisons were performed with a Holm-Sidak or a Dunnett's post hoc test. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Chemicals.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise indicated. A 30-mM stock solution of progesterone was prepared in anhydrous DMSO and stored in aliquots at −20°C until use. Fura 2-AM was purchased from Invitrogen (Burlington, ON, Canada), and a 2-mM stock solution was prepared in anhydrous DMSO and stored at −20°C until needed.

RESULTS

Progesterone modifies contractions but has no effect on Ca2+ transients in field-stimulated cardiomyocytes isolated from female animals.

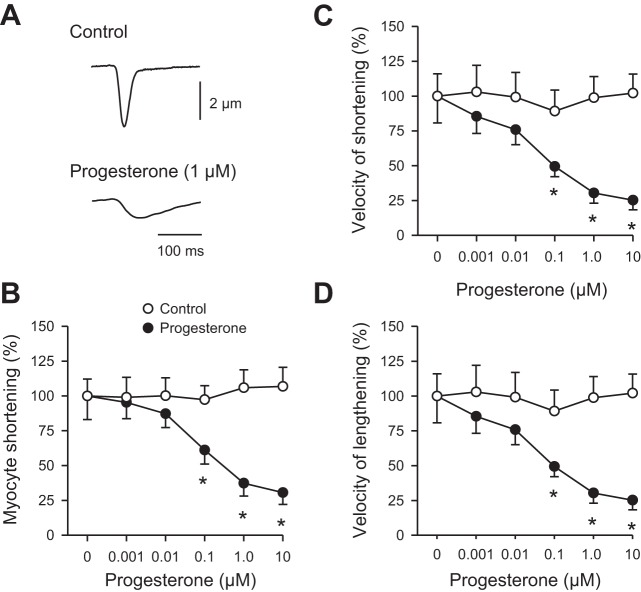

To determine whether progesterone affected the magnitude and time course of contraction in myocytes isolated from female mice, cell shortening was recorded from cells that were field-stimulated at 4 Hz. Figure 2A shows a representative contraction recorded under control conditions (Fig. 2A, top) and in the presence of 1 µM progesterone (Fig. 2A, bottom). This example illustrates that contraction was smaller and slower in the presence of progesterone when compared with vehicle control. Figure 2B shows means (±SE) peak contractions recorded in the absence of progesterone (vehicle control) and in the presence of increasing concentrations of progesterone (0.001–10.0 µM). Contractions were normalized to resting cell length and are expressed as fractional shortening. The maximal concentration of progesterone (10 µM) reduced peak fractional shortening by 71.4% when compared with control (Fig. 2B). The concentration of progesterone that caused 50% inhibition of peak contraction (IC50) was 126.5 ± 54.2 nM (n = 8). Progesterone also attenuated the velocity of shortening (Fig. 2C; IC50 = 69.0 ± 42.9 nM) and the velocity of lengthening (Fig. 2D; IC50 = 11.7 ± 5.4 nM) when compared with cells exposed to vehicle alone.

Fig. 2.

Progesterone inhibited peak contractions and slowed the velocities of shortening and lengthening in field-stimulated myocytes from female mice. A: representative examples of contractions recorded in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of 1 µM progesterone. B: peak cell shortening, normalized to values in the absence of drug, was reduced by progesterone when compared with vehicle control. C and D: velocities of shortening and lengthening (normalized to values in the absence of drug) were slower in cells exposed to progesterone compared with vehicle controls. Values represent means ± SE; n = 7–9 control (8 mice) and n = 12 progesterone-treated cells (9 mice). *Significantly different from vehicle control [P < 0.05, two-way repeated-measures (RM) ANOVA, Holm Sidak post hoc test].

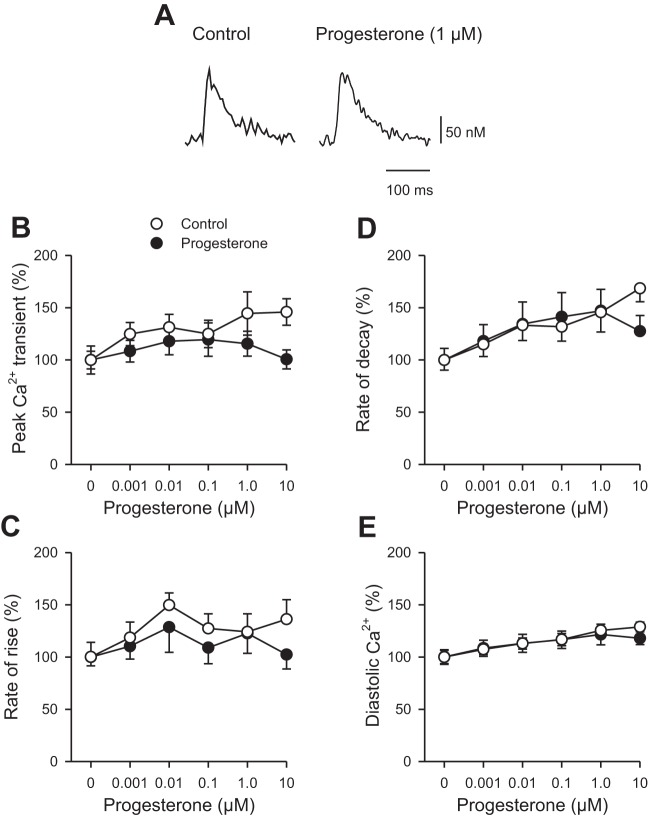

To determine whether changes in the availability of intracellular Ca2+ contributed to the effects of progesterone on contraction, Ca2+ transients were recorded simultaneously in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of drug (0.001–10.0 µM), as shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3A shows representative examples of Ca2+ transients in the absence (Fig. 3A, left) and presence (Fig. 3A, right) of 1 µM progesterone. Progesterone had no significant effect on Ca2+ transients. Indeed, mean data show that peak Ca2+ transients were not affected by progesterone at concentrations up to 10 µM (Fig. 3B). The mean data also demonstrate that progesterone had no effect on either the rate of rise (Fig. 3C) or the rate of decay (Fig. 3D) of the Ca2+ transient. Figure 3E shows that progesterone also had no impact on diastolic Ca2+ concentrations across a range of concentrations. Together, these data show that contractions were attenuated and slowed by acute application of progesterone, with no effect on the underlying Ca2+ transients in myocytes from females.

Fig. 3.

Ca2+ transients recorded from field-stimulated cardiomyocytes isolated from female mice were not affected by acute application of progesterone. A: representative examples of Ca2+ transients in the absence (left) and presence (right) of 1 µM progesterone. B: Peak Ca2+ transient amplitudes, normalized to values in the absence of drug, were not affected by progesterone when compared with vehicle controls. C and D: the rate of rise and the rate of decay (normalized to values in the absence of drug) also were not affected by progesterone. E: diastolic Ca2+ concentrations were not affected by progesterone. Values represent means ± SE; n = 8 control cells (7 mice) and n = 11 cells in the presence of progesterone (9 mice) (P > 0.05, two-way RM ANOVA, Holm Sidak post hoc test).

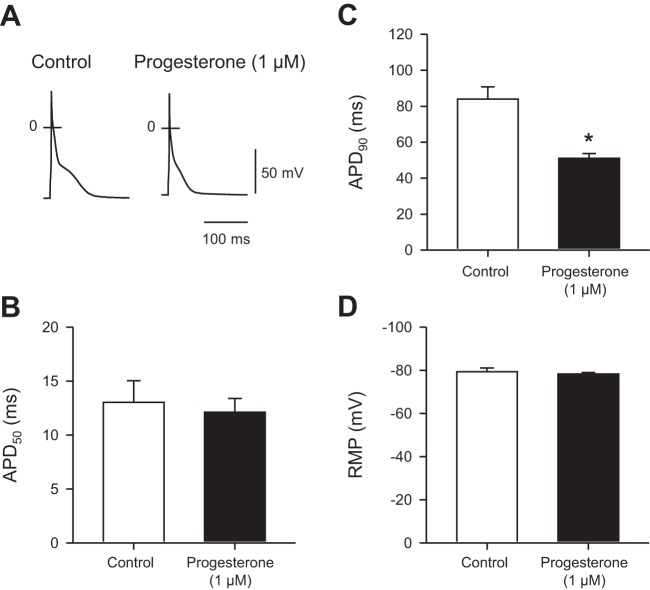

In other experiments, we examined the effect of progesterone on resting membrane potential (RMP) and action potential configuration in myocytes isolated from female mice and paced at 4 Hz. We compared responses from cells exposed to progesterone to cells exposed to vehicle alone. Figure 4A shows representative action potentials recorded in the absence and presence of 1 µM progesterone. Mean data demonstrate that 1 µM progesterone had no effect on APD at 50% repolarization (APD50; Fig. 4B). However, progesterone abbreviated APD at 90% repolarization (APD90; Fig. 4C). By contrast, progesterone had no significant effect on RMP (Fig. 4D). Together, these observations indicate that progesterone abbreviates APD in female mouse ventricular myocytes.

Fig. 4.

Progesterone abbreviated action potential duration (APD) with no effect on resting membrane potential (RMP) in ventricular myocytes from female mice. A: representative action potentials recorded in under control conditions and in the presence of 1 µM progesterone. B and C: mean data show that, while progesterone had no effect on APD at 50% (APD50), it abbreviated APD90. D: application of 1 µM progesterone had no effect on RMP. Values represent means ± SE; n = 10 control myocytes (9 mice) and 9 myocytes in the presence of 1 µM progesterone (4 mice) (*P < 0.05, t-test).

Acute application of progesterone has no effect on Ca2+ handling mechanisms in voltage-clamped cardiomyocytes from female mice.

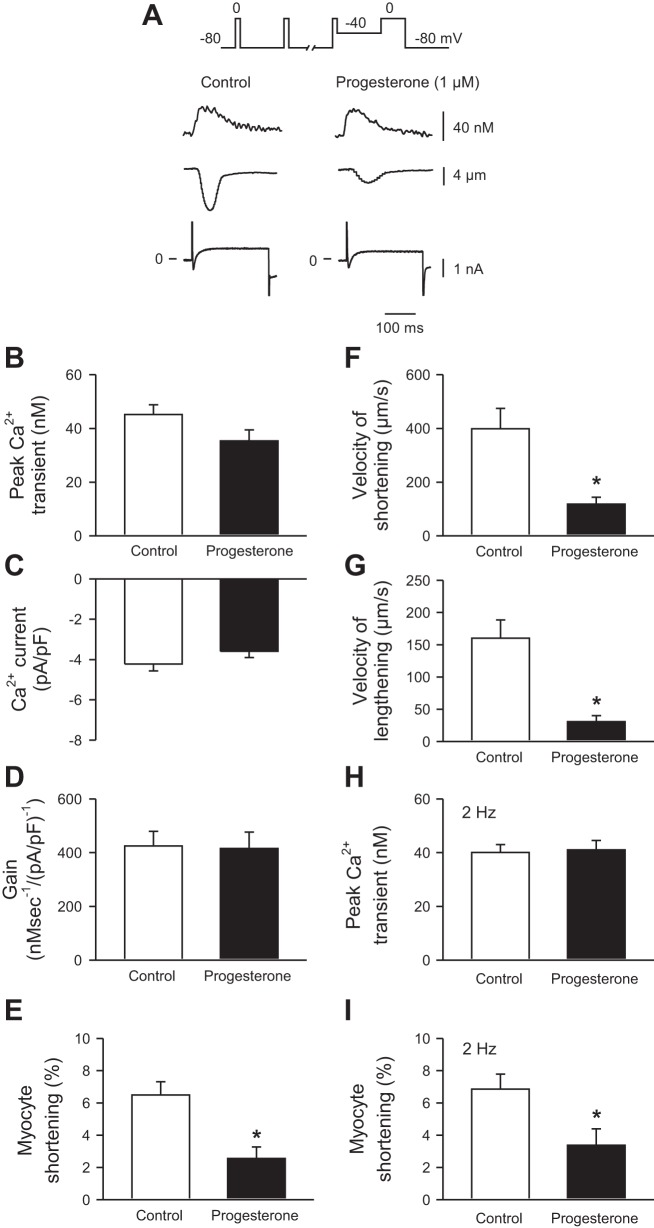

The next series of experiments investigated specific cellular mechanisms that could help explain the effects of progesterone on contraction. These studies used cells that were voltage clamped to eliminate differences in APD and control the duration of depolarization. Cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −80 mV, paced with square conditioning pulses (10 at 4 Hz) from −80 to 0 mV to ensure comparable loading of the SR and repolarized to −40 mV. Cells were then depolarized with a 200-ms test step from −40 to 0 mV to activate ICa-L in the absence or presence of 1 µM progesterone. This concentration was chosen because it had near maximal effects on contraction, as shown in Fig. 2. Figure 5A shows representative examples of Ca2+ transients (Fig. 5A, top), contractions (Fig. 5A, middle), and ICa-L (Fig. 5A, bottom) under control conditions and after exposure to 1 µM progesterone. Means (±SE) data demonstrate that peak Ca2+ transients (Fig. 5B) and ICa-L densities (Fig. 5C) were not affected by progesterone. The amount of Ca2+ released per unit ICa-L, a parameter known as the gain of SR Ca2+ release, also was not affected by progesterone (Fig. 5D). By contrast, peak contractions were inhibited by progesterone (Fig. 5E) and the velocities of shortening and lengthening were slowed (Fig. 5, F and G). Progesterone also inhibited contraction with no effect on Ca2+ transients when cells were voltage-clamped and paced with conditioning pulses delivered at slower frequency (e.g., 2 Hz), as shown in Fig. 5, H and I. These data demonstrate that progesterone attenuated and slowed contractions in cells from female mice, even when the duration of depolarization was controlled by voltage clamp and the history of SR Ca2+ loading was identical in control and drug-treated cells.

Fig. 5.

Progesterone reduced peak contractions and slowed relaxation with no effect on other Ca2+ handling mechanisms in voltage-clamped myocytes from female mice. A: the voltage-clamp protocol is shown at the top. Representative Ca2+ transients (top), contractions (middle), and ICa-L (bottom) recorded in the absence (left) and presence (right) of 1 µM progesterone. B and C: Ca2+ transient amplitudes and peak ICa-L were similar in control and drug-treated cells. D: the gain of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release, expressed as the amount of Ca2+ released per unit ICa-L, was similar in the absence and presence of progesterone. E, F, and G: peak contractions as well as the velocities of shortening and lengthening were attenuated by progesterone when compared with vehicle control. H and I: in cells paced at 2 Hz, Ca2+ transients were unaffected by 1 µM progesterone, but contractions were attenuated. Values represent means ± SE; n = 7–14 control cells (7–11 mice) and 8–14 progesterone-treated cells (6–8 mice) for cells paced at 4 Hz. Data at 2 Hz were obtained from 16 to 17 control (13 mice) and 8–15 progesterone-treated cells (5–7 mice). *Significantly different from vehicle control (P < 0.05, t-test).

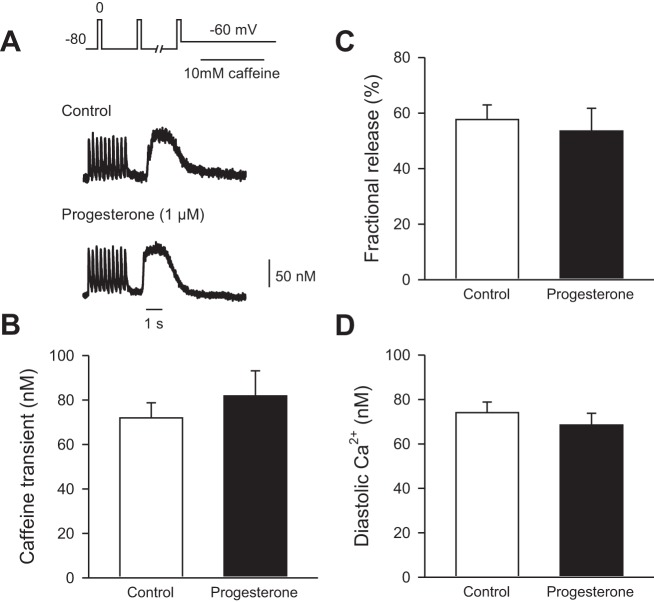

We next investigated whether the amount of SR Ca2+ available for release was modified by progesterone. SR Ca2+ load was measured by the rapid application of 10 mM caffeine as described in methods. Figure 6A shows examples of Ca2+ transients followed by caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients in the absence (Fig. 6A, top) and presence (Fig. 6A, bottom) of 1 µM progesterone. The mean (±SE) data show that SR Ca2+ load was similar in control and progesterone-treated cells (Fig. 6B). Fractional SR Ca2+ release, which represents the amount of Ca2+ released as a fraction of the total SR Ca2+ available, also was similar in the two groups (Fig. 6C). Similarly, diastolic Ca2+ levels under voltage-clamp conditions (Fig. 6D) were not affected by progesterone. Taken together, these data show that the smaller, slower contractions observed after acute application of progesterone in female ventricular myocytes are not attributable to changes in ICa-L, SR Ca2+ release gain, or the amount of SR Ca2+ available for release.

Fig. 6.

SR Ca2+ content and fractional SR Ca2+ release were unaffected by progesterone treatment in cells from female mice. A: representative examples of a train of Ca2+ transients followed by caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of 1 µM progesterone. B: SR Ca2+ content was similar in control and progesterone-treated cells. C: fractional SR release was not affected by progesterone. D: diastolic Ca2+ levels were similar in the absence and presence of drug. Values represent means ± SE; n = 7–14 control cells (6 mice) and 8–14 progesterone-treated cells (5 mice; t-test).

Myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is reduced, whereas myosin binding protein C phosphorylation is enhanced, by acute application of progesterone in hearts from female mice.

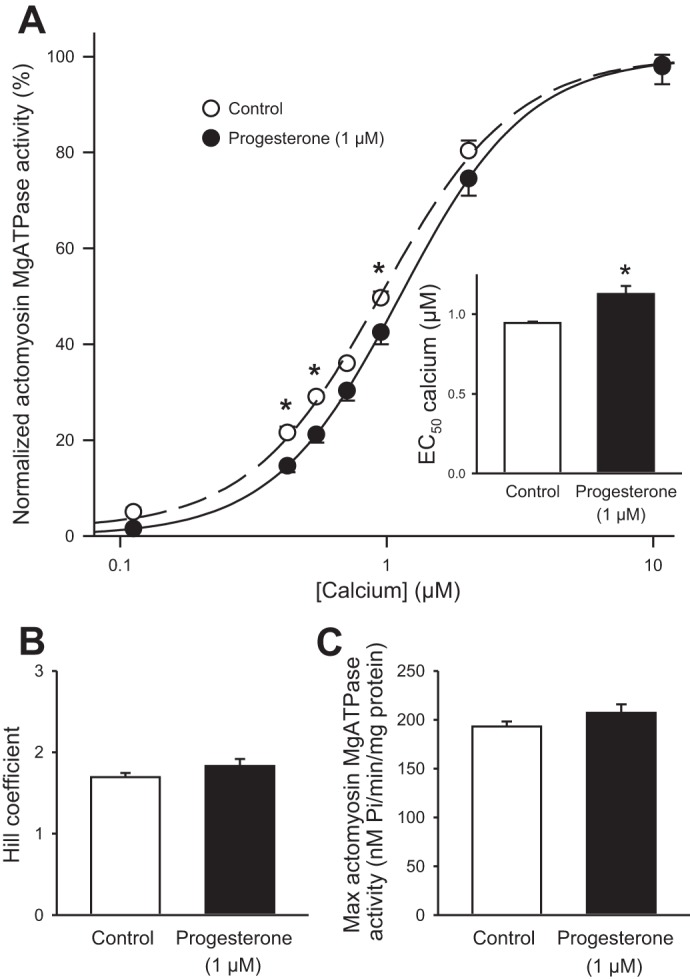

As progesterone attenuated contraction with no effect on Ca2+ transients in cells from females, it is possible that progesterone influenced contractile function at the level of the cardiac myofilaments. In these experiments, actomyosin MgATPase activity was measured to determine whether progesterone affected myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. Hearts were perfused with either 1 µM progesterone or vehicle control for 35 min, as described in methods. Figure 7A shows normalized actomyosin MgATPase activity in control and progesterone-treated ventricles. The curve for progesterone-treated hearts was shifted to the right, which demonstrates that drug treatment reduced myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 7A). This was quantified by comparing the concentration of Ca2+ required to produce 50% of maximal activity (EC50 values) in each group. Results showed that the EC50 values were significantly larger in progesterone-treated hearts than in control hearts (Fig. 7A, inset). By contrast, progesterone had no effect on either the Hill coefficient (Fig. 7B) or the maximal ATPase activity (Fig. 7C). These results demonstrate that myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was reduced by acute exposure to progesterone.

Fig. 7.

Progesterone reduced myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in hearts from females. A: actomyosin MgATPase activity, normalized to the maximum at 10 µM Ca2+, was significantly lower in hearts treated with 1 µM progesterone when compared with vehicle control. The EC50 values for Ca2+ also were increased by progesterone treatment (inset). B: the Hill coefficient was not influenced by progesterone. C: maximum actomyosin MgATPase activity was similar in control and progesterone-treated hearts. Values represent means ± SE; n = 7 control and n = 6 progesterone-treated hearts *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05, two-way RM ANOVA, Holm Sidak post hoc test, t-test).

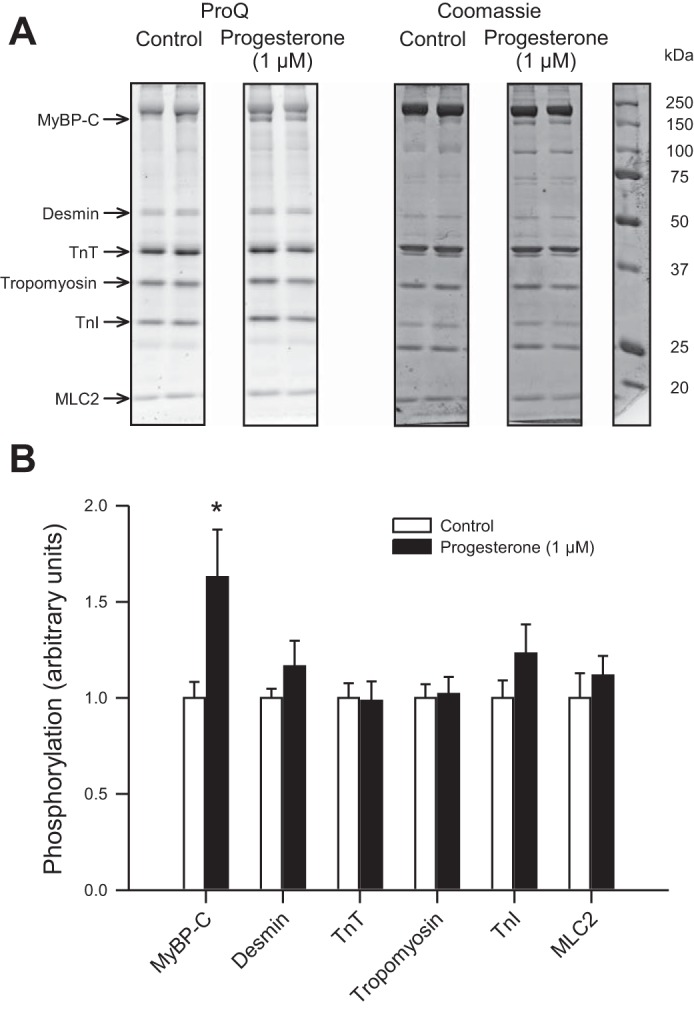

As cardiac contractile function is profoundly influenced by phosphorylation changes in myofilament proteins, we compared phosphorylation levels of key myofilament proteins in control and progesterone-treated (1 µM) hearts. A representative gel is shown in Fig. 8A and mean (±SE) data are shown in Fig. 8B. Results showed that myosin binding protein C phosphorylation was increased by progesterone treatment (Fig. 8, A and B). By contrast, phosphorylation levels for other myofilament proteins (desmin, troponin T, tropomyosin, troponin I, and myosin light chain 2) were not significantly affected by drug treatment (Fig. 8, A and B). Together, these data indicate that acute application of progesterone reduces myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity but increases phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C.

Fig. 8.

Progesterone increased phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C in hearts from female mice. A: myofilament proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with ProQ Diamond (left) to evaluate myofilament protein phosphorylation. Total protein load was determined by staining gels with Coomassie (middle). Protein marker (right) shows the approximate molecular weights of myofilament proteins. B: mean data demonstrate that hearts that were perfused with progesterone (1 µM) had significantly higher levels of myosin binding protein C phosphorylation when compared with hearts perfused with vehicle control alone. Phosphorylation of other myofilament proteins was not affected by progesterone. Data in B were normalized to myosin. MyBP-C, myosin binding protein C; TnT, troponin T; TnI, troponin I; MLC2, myosin light chain 2. Values represent means ± SE; n = 7 control and n = 6 progesterone-treated hearts. *Significant difference from vehicle control (P < 0.05, t-test).

Acute effects of progesterone on myocyte contraction were blocked by a PR antagonist and reversed by the Ca2+ sensitizer levosimendan.

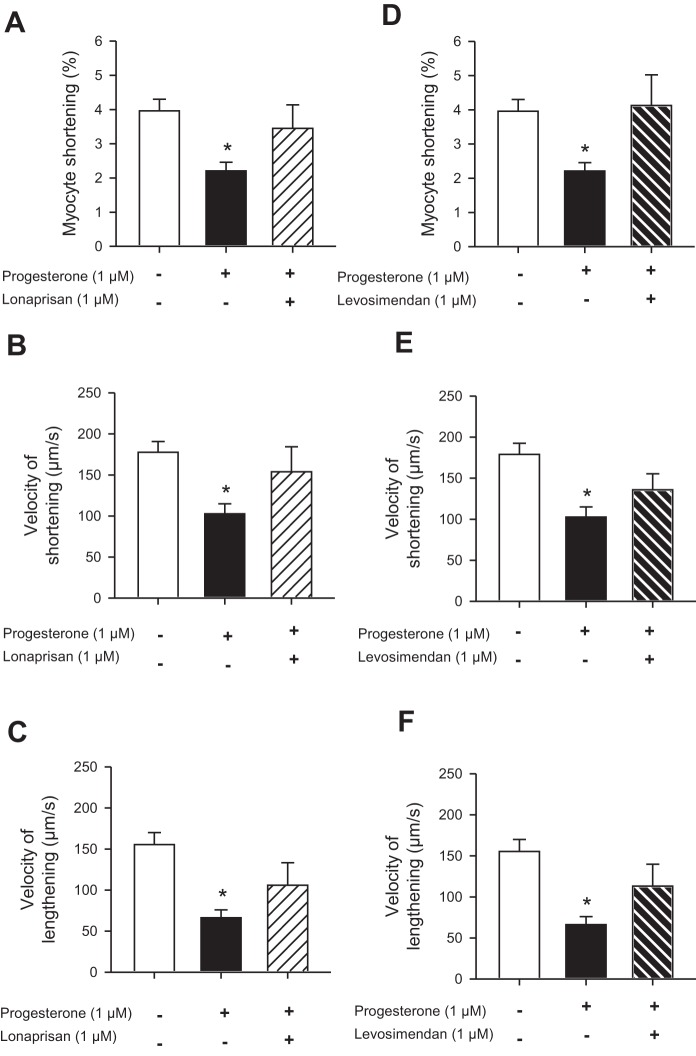

We also investigated whether the acute effects of progesterone on cardiomyocyte contraction could be blocked by progesterone antagonists. For these experiments we treated cells with two different PR antagonists, mifepristone (10 µM; 47), and lonaprisan (1 µM; 21), in the presence of 1 µM progesterone. Interestingly, mifepristone did not block the effects of progesterone on peak contraction; peak contractions were 2.2 ± 0.3% in progesterone alone (n = 10) and 1.4 ± 0.5% in progesterone plus mifepristone (n = 3; not significantly different). Furthermore, mifepristone also inhibited contraction, even in the absence of progesterone (peak contraction was 1.9 ± 0.5% in the presence of mifepristone alone; n = 3). By contrast, the PR antagonist lonaprisan abolished the inhibitory effect of progesterone on the amplitude of contraction (Fig. 9A). Lonaprisan also reversed the effects of progesterone on velocities of shortening and lengthening (Fig. 9, B and C). These findings indicate that acute effects of progesterone on contraction were receptor mediated.

Fig. 9.

The effects of progesterone on contraction were inhibited by the progesterone receptor (PR) antagonist lonaprisan and reversed by the Ca2+ sensitizer levosimendan in cells from females. A: progesterone (1 µM) inhibited contraction; this effect was abolished when the PR antagonist lonaprisan (1 µM) was applied together with progesterone. B and C: lonaprisan also blocked the effect of progesterone on the velocities of shortening and lengthening. D: the Ca2+ sensitizer levosimendan (1 µM) reversed the inhibitory effect of progesterone on peak contraction. E and F: levosimendan also antagonized the effect of progesterone on the velocities of shortening and lengthening. Values represent means ± SE; n = 32 control cells (10 mice), 10 progesterone-treated cells (10 mice), 5 lonaprisan-treated cells (5 mice), and 6 levosimendan-treated cells (6 mice). *Significantly different from vehicle control (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test).

In other experiments, we investigated whether the effects of progesterone could be reversed by treatment with the Ca2+ sensitizer levosimendan (1 µM; 11). Figure 9D shows that, when cells were treated with progesterone plus levosimendan, the inhibitory effect of progesterone on contraction was abolished. Levosimendan also reversed the effects of progesterone on the velocity of shortening and lengthening (Fig. 9, E and F). These data suggest that the effects of progesterone on contraction can be reversed if the myofilaments are sensitized to Ca2+.

Acute application of progesterone has no effect on myocyte contraction or myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in hearts from male mice.

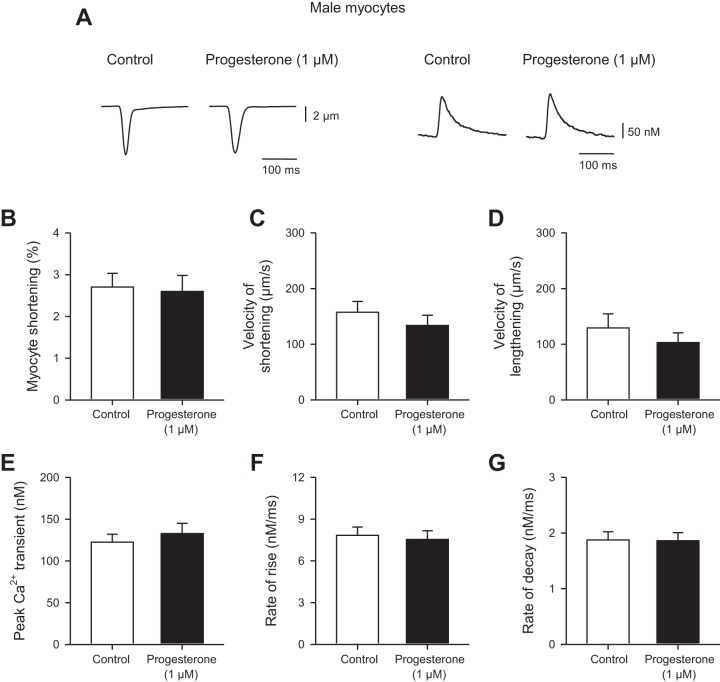

In some experiments we investigated whether progesterone affected the magnitude and time course of contractions and Ca2+ transients in ventricular myocytes isolated from male mice. Cells were field-stimulated at 4 Hz. Figure 10A shows representative contractions (Fig. 10, left) and Ca2+ transients (Fig. 10, right) in the absence and presence of 1 µM progesterone. The mean data show that progesterone had no effect on either the amplitude (Fig. 10B) or the velocities of shortening (Fig. 10C) or lengthening (Fig. 10D). We also found that 1 µM progesterone had no significant effect on either the amplitude or time course of the Ca2+ transients (Fig. 10, E–G). Thus, unlike our observations in ventricular myocytes from female mice, progesterone had no effect on magnitude or the time course of contraction in cells from male mice.

Fig. 10.

Progesterone had no effect on the amplitudes or timing of contractions and Ca2+ transients in field-stimulated myocytes from male mice. A: representative examples of contractions (left) and Ca2+ transients (right) recorded in the absence and presence of 1 µM progesterone in cells from males paced at 4 Hz. B: peak myocyte shortening was not affected by progesterone in cells from males. C and D: velocities of shortening and lengthening were similar in cells exposed to progesterone and in vehicle controls. E, F, and G: progesterone had no impact on either the time course or the amplitude of Ca2+ transients in cells from males. Values represent means ± SE; n = 12 control and n = 12 progesterone-treated cells isolated from 6 mice/group (t-test for all except velocity of lengthening and decay rate, where a Mann-Whitney U-test was used).

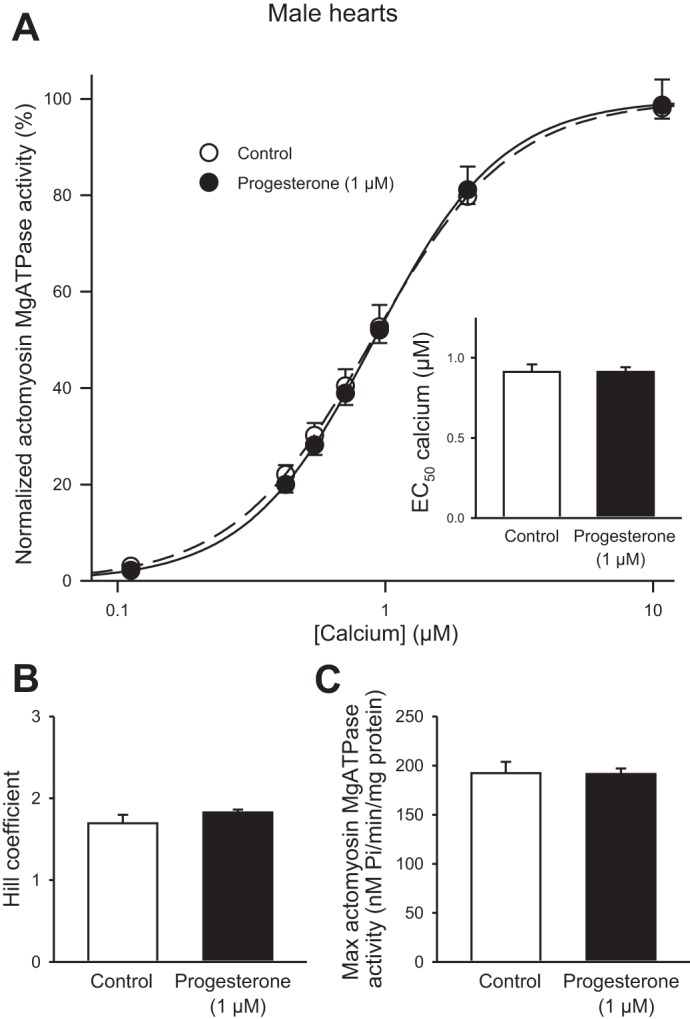

We also investigated whether progesterone affected myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in hearts from male mice. Hearts were perfused with either 1 µM progesterone or vehicle control for 35 min. Figure 11A shows that progesterone had no effect on actomyosin Mg2+ATPase activity across a range of Ca2+ concentrations in hearts from male mice. The EC50 values also were similar in the two groups (Fig. 11A, inset). In addition, progesterone had no effect on either the Hill coefficient (Fig. 11B) or the maximal ATPase activity (Fig. 11C). These results demonstrate that, unlike our findings in hearts from females, myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was not affected by acute exposure to progesterone.

Fig. 11.

Progesterone treatment had no impact on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in male hearts. A: actomyosin MgATPase activity, normalized to the maximum at 10 µM Ca2+, was not affected by progesterone treatment (1 µM) when compared with vehicle control in males. The EC50 values for Ca2+ were similar in control and progesterone-treated male hearts (inset). B and C: neither the Hill coefficients nor the maximum actomyosin MgATPase activity were influenced by progesterone in male hearts. Values represent means ± SE; n = 6 control and n = 6 progesterone-treated hearts (two-way RM ANOVA, Holm Sidak post hoc test, t-test).

DISCUSSION

The overall goals of this study were to evaluate the acute effects of progesterone on contractions and Ca2+ homeostasis in ventricular myocytes from female mice and to investigate the cellular mechanisms involved. Field-stimulated myocytes exposed to progesterone had smaller, slower contractions than vehicle control, with no change in RMP or action potential characteristics. Interestingly, progesterone had no effect on the amplitudes or time courses of Ca2+ transients recorded at the same time as contractions, although it did abbreviate APD90. Smaller, slower contractions with no change in Ca2+ transients also were observed in voltage-clamped cells depolarized with identical test steps. Voltage-clamp experiments showed that progesterone had no effect on cellular mechanisms that regulate intracellular Ca2+ handling, including ICa-L, the gain of SR Ca2+ release, diastolic Ca2+, SR Ca2+ content, and fractional SR Ca2+ release. By contrast, acute exposure to progesterone reduced myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in conjunction with an increase in phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C when compared with hearts perfused with vehicle alone. The effects of progesterone on contraction in myocytes from female mice were reversed by the PR antagonist lonaprisan and by the Ca2+ sensitizer, levosimendan. Interestingly, progesterone had no effect on contractions or myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in cells or hearts from male mice. Together, these findings demonstrate that short-term exposure to progesterone inhibits cardiac contraction in the female heart by effects on myofilaments, with no effect on other major cellular Ca2+ handling mechanisms.

Classic studies have shown that acute application of progesterone (0.1–10 µM) reduces peak contractile force in ventricular muscle preparations from a pooled sample of male and female guinea pigs (42), although studies in males alone report no effect on contraction (68, but cf. 56). Our study extends this early work to show that progesterone reduced peak contractions and prolonged the rates of shortening and lengthening in ventricular myocytes isolated from female mice but not in cells from male mice. Although PRs have been identified in hearts from males and females (45), it is unclear whether there are sex differences in cardiac PR density or distribution. There is evidence that brain PR expression is lower in males than in females and this has been attributed to induction of PRs by circulating estradiol (54). Whether this occurs in other tissues such as the heart is not yet clear. Nonetheless, our data strongly suggest that progesterone attenuates and slows contractions in hearts from females and that this effect is not seen in cells from males.

This negative inotropic effect of progesterone has been attributed to a decrease in APD that would, theoretically, reduce Ca2+ influx and attenuate peak contraction (42). Indeed, there is evidence that progesterone reduces APD in guinea pig ventricular myocytes from females (47) and in papillary muscles from a pooled group of males and females (42), although this has not been reported in all studies (13, 68). Here, we showed that acute application of progesterone abbreviated APD90 in ventricular myocytes from female mice, so it is possible that shorter action potentials could account for inhibition of contraction in field-stimulated myocytes. However, a key finding in our study is the novel observation that the effects of progesterone on contraction were not accompanied by corresponding changes in Ca2+ transients. This was true not only in field stimulation studies, when responses were activated by action potentials, but also in voltage clamp studies, when responses were activated by test steps of fixed duration to eliminate differences in the duration of depolarization. This suggests that acute application of progesterone modifies Ca2+ handling at the cellular level. We demonstrated that progesterone had no effect on ICa-L in mouse ventricular myocytes and this concurs with an earlier study in female guinea pig ventricular myocytes (47). These data indicate that the trigger for SR Ca2+ release is not affected by this hormone. We also showed that progesterone had no effect on the gain of SR Ca2+ release, the levels of diastolic Ca2+, the amount of Ca2+ available for release in the SR, or the fraction of Ca2+ released from the SR per beat. These findings clearly show that the effects of progesterone on contraction are not mediated by changes in any of these critical Ca2+-handling mechanisms.

An earlier study showed that acute effects of progesterone on ionic currents in the guinea pig heart could be blocked by the PR antagonist mifepristone (47). Interestingly, we found that mifepristone did not block the effects of progesterone on contraction and it actually attenuated contractions when applied in the absence of progesterone. There is evidence that many PR antagonists, including mifepristone, may actually be partial agonists in some tissues and species (1) and our findings suggest that mifepristone may act in this way in murine ventricular muscle. On the other hand, we showed that the attenuation and slowing of contraction caused by progesterone could be reversed by the PR antagonist, lonaprisan. Lonaprisan is a potent and selective PR antagonist (21) without the partial agonist actions of mifepristone (1). Taken together, our results indicate that lonaprisan is an effective antagonist of acute effects of progesterone in the heart whereas mifepristone is not.

A novel observation reported here is that the myofilaments themselves are influenced by exposure to progesterone. Our data demonstrate that acute exposure to progesterone causes a decrease in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity but only in female hearts. These findings strongly suggest that a reduction in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity contributes importantly to the inhibition of cardiac contraction in the female heart. We found that we could reverse effects of progesterone on the magnitude and velocity of contraction by exposing cells to the Ca2+ sensitizer levosimendan. Levosimendan is thought to increase cardiac contractility primarily by Ca2+ sensitization of troponin C, although it does have other relevant pharmacological actions such inhibition of phosphodiesterase III (52). Nonetheless, our results demonstrate that levosimendan can reverse the inhibitory effects of progesterone in the heart, which suggests that a reduction in the Ca2+ sensitivity of troponin C may be involved.

Interestingly previous studies have reported that decreased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is associated with increased rates of relaxation (33), which is in disagreement with our data. However, others have shown no change in relaxation with decreased Ca2+ sensitivity (18), suggesting that the link between myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and activation-relaxation dynamics is not clear. Some possible changes that may explain the progesterone-dependent slowing of cellular relaxation are Ca2+-independent factors such as titin. Although titin was not investigated in the current study, acute changes in its phosphorylation level can affect cellular recoil and thus rate of relaxation. Whether titin phosphorylation is impacted by acute progesterone exposure could be the subject of a future investigation.

We found that acute administration of progesterone increased myosin binding protein C phosphorylation, with no effects on the total phosphorylation of other myofilament proteins such as desmin, troponin T, tropomyosin, tropo nin I, and myosin light chain 2. Interestingly, previous work by our group and others has suggested that phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C may be sufficient to reduce myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (12, 39, 60). Whether increased phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C can account for the reduced myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity seen in the presence of progesterone is less clear. Cuello et al. (17) reported that ribosomal S6 kinase phosphorylation of serine 282 reduces myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, but they found that this change in Ca2+ sensitivity occurs in conjunction with an increased rate of cross-bridge cycling, which is inconsistent with our results. Other phosphorylation sites within myosin binding protein that have been investigated are serines 273 and 302; however, the functional roles of these amino acids are not clear (57). More recently others have identified up to 17 potential phosphorylation sites within myosin binding protein C and the functional impact of these sites remains largely unexplored (36). Therefore, while we have uncovered a novel phosphorylation change in myosin binding protein C following acute progesterone exposure of the heart, we are unable to conclusively identify this change as the causative player in the observed alterations in myofilament function.

The receptor or receptors responsible for nongenomic effects of progesterone have not been conclusively identified, although evidence for membrane-associated PRs coupled to a variety of different signaling pathways is growing (59, 64). Acute progesterone treatment of a variety of cell types activates protein kinase A (51, 61), protein kinase C (3), as well as Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (4). Interestingly, each of these molecular messengers has been shown to phosphorylate cardiac myosin binding protein C (5). In cardiomyocytes there is some evidence that membrane receptors PR78 and/or PR54 may be involved in the nongenomic effects of progesterone (47), although further studies to identify myocardial PRs and clarify the associated signaling pathways that are needed.

There are limitations to this study. We found that acute progesterone attenuated and slowed cardiomyocyte contractions at concentrations as low as 100 nM and that effects were maximal at 1 µM. Circulating progesterone levels are close to 2.5 nM in postmenopausal women and in premenopausal women in the follicular phase (24, 30). Levels can rise to 40.6 nM in premenopausal women in the luteal phase (30), but still progesterone would be expected to have little, if any, effect on cardiac contraction under these conditions. Progesterone levels do rise during pregnancy and can reach 300–1200 nM by the third trimester (24). It is well established that cardiac output increases throughout pregnancy as stroke volume and heart rate increase (62). Thus it is possible that acute effects of progesterone on contraction may be at least partially compensated by other actions potentially including chronic actions of progesterone. For example, there is some evidence that chronic exposure to progesterone may actually increase myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (31). Thus inhibitory effects of progesterone on cardiac contractile function may not normally be apparent. However, our data suggest that inhibitory effects of progesterone on contraction can occur at physiological concentrations and may contribute to or exacerbate manifestations of cardiovascular disease late in pregnancy. It is also important to note that progesterone is also produced by the adrenal glands under stressful conditions (65). Indeed, studies have shown that serum progesterone levels increase from ~30 nM to between 100 and 300 nM in rats exposed to stressors such as foot shock and cold restraint (29, 31). Therefore, it is possible that progesterone also may disrupt cardiac contractile function during exposure to stress. Interestingly, one clinical study has shown that higher progesterone levels are associated with an increased prevalence of congestive heart failure (48). Additional studies that investigate potential links between progesterone and heart failure in the setting of stress or pregnancy would be of interest.

We have previously shown that the estrous stage can influence cardiac contractile function in female mice (39). Mice in estrus have longer APD, larger contractions and Ca2+ transients, and reduced myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity when compared with the other stages (39). However, we also demonstrated that group-housed female mice, such as those used in the present study, do not exhibit regular estrous cycles unless they are specifically induced to cycle by exposure to male bedding (39). Cycling mice spend less than 10% of their reproductive cycle in estrus (6), so the chance that even a cycling mouse used in any given experiment will be in estrus is very low. A key reason for not including female animals in experimental studies is the belief that confounding contributions from the estrous cycle will make results variable and difficult to interpret, although there is no evidence for this (16, 34, 40). Indeed, Zucker and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 293 articles that examined behavioral, morphological, physiological, and molecular traits in males and in females, without regard to estrous stage (53). They showed that variability was typically similar in males and females (or actually higher in males for several traits) and concluded that utilization of female animals does not require continuous monitoring of the estrous cycle (53). For these reasons we did not select mice in a particular estrous stage in the present study.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that acute exposure to progesterone reduced the amplitude of contraction with no impact on Ca2+ transients in ventricular myocytes isolated from female mice. Progesterone also abbreviated APD but had no effect on cellular mechanisms that regulate SR Ca2+ release, so the effect on contraction was not attributable to changes in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Instead, the smaller, slower contractions observed in the presence of progesterone reflected a reduction in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. In contrast to results in females, progesterone had no effect on contractions or myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in myocytes and hearts from males. Together, these observations indicate that progesterone attenuates and slows cardiac contraction through nongenomic actions on the myofilaments in the female heart. These effects of progesterone may contribute to or exacerbate cardiovascular complications of pregnancy.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Grant MOP 97973 (to S. E. Howlett) and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant RGPIN 261928 (to W. G. Pyle).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.A.F., J.K.M., A.G., W.G.P., and S.E.H. performed experiments; H.A.F., J.K.M., A.G., W.G.P., and S.E.H. analyzed data; H.A.F., J.K.M., A.G., W.G.P., and S.E.H. interpreted results of experiments; H.A.F., J.K.M., A.G., W.G.P., and S.E.H. prepared figures; H.A.F., J.K.M., W.G.P., and S.E.H. drafted manuscript; H.A.F., J.K.M., A.G., W.G.P., and S.E.H. edited and revised manuscript; H.A.F., J.K.M., A.G., W.G.P., and S.E.H. approved final version of manuscript.

AKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jie-Quan Zhu and Peter Nicholl for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afhüppe W, Beekman JM, Otto C, Korr D, Hoffmann J, Fuhrmann U, Möller C. In vitro characterization of ZK 230211–a type III progesterone receptor antagonist with enhanced antiproliferative properties. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 119: 45–55, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayaz O, Howlett SE. Testosterone modulates cardiac contraction and calcium homeostasis: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Biol Sex Differ 6: 9, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0027-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasubramanian B, Portillo W, Reyna A, Chen JZ, Moore AN, Dash PK, Mani SK. Nonclassical mechanisms of progesterone action in the brain: I. Protein kinase C activation in the hypothalamus of female rats. Endocrinology 149: 5509–5517, 2008. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramanian B, Portillo W, Reyna A, Chen JZ, Moore AN, Dash PK, Mani SK. Nonclassical mechanisms of progesterone action in the brain: II. Role of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in progesterone-mediated signaling in the hypothalamus of female rats. Endocrinology 149: 5518–5526, 2008. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardswell SC, Cuello F, Kentish JC, Avkiran M. cMyBP-C as a promiscuous substrate: phosphorylation by non-PKA kinases and its potential significance. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 33: 53–60, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10974-011-9276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkley MS, Bradford GE. Estrous cycle dynamics in different strains of mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 167: 70–77, 1981. doi: 10.3181/00379727-167-41127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell JR, Bernasochi GB, Varma U, Raaijmakers AJ, Delbridge LM. Sex and sex hormones in cardiac stress—mechanistic insights. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 137: 124–135, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bers DM. Cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak: basis and roles in cardiac dysfunction. Annu Rev Physiol 76: 107–127, 2014. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buonanno C, Arbustini E, Rossi L, Dander B, Vassanelli C, Paris B, Poppi A. Left ventricular function in men and women. Another difference between sexes. Eur Heart J 3: 525–528, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke JH, Goldberger JJ, Ehlert FA, Kruse JT, Parker MA, Kadish AH. Gender differences in heart rate before and after autonomic blockade: evidence against an intrinsic gender effect. Am J Med 100: 537–543, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler L, Cros C, Oldman KL, Harmer AR, Pointon A, Pollard CE, Abi-Gerges N. Enhanced characterization of contractility in cardiomyocytes during early drug safety assessment. Toxicol Sci 145: 396–406, 2015. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen PP, Patel JR, Rybakova IN, Walker JW, Moss RL. Protein kinase A-induced myofilament desensitization to Ca(2+) as a result of phosphorylation of cardiac myosin-binding protein C. J Gen Physiol 136: 615–627, 2010. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng J, Ma X, Zhang J, Su D. Diverse modulating effects of estradiol and progesterone on the monophasic action potential duration in Langendorff-perfused female rabbit hearts. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 26: 219–226, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2010.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung E, Yeung F, Leinwand LA. Calcineurin activity is required for cardiac remodelling in pregnancy. Cardiovasc Res 100: 402–410, 2013. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung E, Yeung F, Leinwand LA. Akt and MAPK signaling mediate pregnancy-induced cardiac adaptation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 1564–1575, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00027.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clayton JA, Collins FS. Policy: NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature 509: 282–283, 2014. doi: 10.1038/509282a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuello F, Bardswell SC, Haworth RS, Ehler E, Sadayappan S, Kentish JC, Avkiran M. Novel role for p90 ribosomal S6 kinase in the regulation of cardiac myofilament phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 286: 5300–5310, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Tombe PP, Belus A, Piroddi N, Scellini B, Walker JS, Martin AF, Tesi C, Poggesi C. Myofilament calcium sensitivity does not affect cross-bridge activation-relaxation kinetics. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1129–R1136, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00630.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrier GR, Redondo IM, Mason CA, Mapplebeck C, Howlett SE. Regulation of contraction and relaxation by membrane potential in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1618–H1626, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrier GR, Smith RH, Howlett SE. Calcium sparks in mouse ventricular myocytes at physiological temperature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1495–H1505, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00802.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuhrmann U, Hess-Stumpp H, Cleve A, Neef G, Schwede W, Hoffmann J, Fritzemeier KH, Chwalisz K. Synthesis and biological activity of a novel, highly potent progesterone receptor antagonist. J Med Chem 43: 5010–5016, 2000. doi: 10.1021/jm001000c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics–2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 127: e6–e245, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein J, Sites CK, Toth MJ. Progesterone stimulates cardiac muscle protein synthesis via receptor-dependent pathway. Fertil Steril 82: 430–436, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomella L, Haist S. Laboratory diagnosis: chemistry, immunology, serology. In: Clinician’s Pocket Reference (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gongora MC, Wenger NK. Cardiovascular complications of pregnancy. Int J Mol Sci 16: 23905–23928, 2015. doi: 10.3390/ijms161023905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greiten LE, Holditch SJ, Arunachalam SP, Miller VM. Should there be sex-specific criteria for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure? J Cardiovasc Transl Res 7: 139–155, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9514-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grohé C, Kahlert S, Löbbert K, Stimpel M, Karas RH, Vetter H, Neyses L. Cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts contain functional estrogen receptors. FEBS Lett 416: 107–112, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanley PC, Zinsmeister AR, Clements IP, Bove AA, Brown ML, Gibbons RJ. Gender-related differences in cardiac response to supine exercise assessed by radionuclide angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 13: 624–629, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hueston CM, Deak T. On the time course, generality, and regulation of plasma progesterone release in male rats by stress exposure. Endocrinology 155: 3527–3537, 2014. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janse de Jonge XA, Boot CR, Thom JM, Ruell PA, Thompson MW. The influence of menstrual cycle phase on skeletal muscle contractile characteristics in humans. J Physiol 530: 161–166, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0161m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalász J, Tóth EP, Bódi B, Fagyas M, Tóth A, Pal BH, Vari SG, Balog M, Blažetić S, Heffer M, Papp Z, Borbély A. Single acute stress-induced progesterone and ovariectomy alter cardiomyocyte contractile function in female rats. Croat Med J 55: 239–249, 2014. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2014.55.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katoh H, Schlotthauer K, Bers DM. Transmission of information from cardiac dihydropyridine receptor to ryanodine receptor: evidence from BayK 8644 effects on resting Ca(2+) sparks. Circ Res 87: 106–111, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kentish JC, McCloskey DT, Layland J, Palmer S, Leiden JM, Martin AF, Solaro RJ. Phosphorylation of troponin I by protein kinase A accelerates relaxation and crossbridge cycle kinetics in mouse ventricular muscle. Circ Res 88: 1059–1065, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein SL, Schiebinger L, Stefanick ML, Cahill L, Danska J, de Vries GJ, Kibbe MR, McCarthy MM, Mogil JS, Woodruff TK, Zucker I. Opinion: Sex inclusion in basic research drives discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 5257–5258, 2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502843112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knowlton AA, Lee AR. Estrogen and the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Ther 135: 54–70, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kooij V, Holewinski RJ, Murphy AM, Van Eyk JE. Characterization of the cardiac myosin binding protein-C phosphoproteome in healthy and failing human hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 60: 116–120, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li GR, Ferrier GR, Howlett SE. Calcium currents in ventricular myocytes of prehypertrophic cardiomyopathic hamsters. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 268: H999–H1005, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lizotte E, Grandy SA, Tremblay A, Allen BG, Fiset C. Expression, distribution and regulation of sex steroid hormone receptors in mouse heart. Cell Physiol Biochem 23: 75–86, 2009. doi: 10.1159/000204096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacDonald JK, Pyle WG, Reitz CJ, Howlett SE. Cardiac contraction, calcium transients, and myofilament calcium sensitivity fluctuate with the estrous cycle in young adult female mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H938–H953, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00730.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maric-Bilkan C, Arnold AP, Taylor DA, Dwinell M, Howlett SE, Wenger N, Reckelhoff JF, Sandberg K, Churchill G, Levin E, Lundberg MS. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on Sex Differences Research in Cardiovascular Disease: scientific questions and challenges. Hypertension 67: 802–807, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marsh JD, Lehmann MH, Ritchie RH, Gwathmey JK, Green GE, Schiebinger RJ. Androgen receptors mediate hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes. Circulation 98: 256–261, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendoza J, De Mello WC. Influence of progesterone on membrane potential and peak tension of myocardial fibres. Cardiovasc Res 8: 352–361, 1974. doi: 10.1093/cvr/8.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merz CN, Moriel M, Rozanski A, Klein J, Berman DS. Gender-related differences in exercise ventricular function among healthy subjects and patients. Am Heart J 131: 704–709, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(96)90274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer R, Linz KW, Surges R, Meinardus S, Vees J, Hoffmann A, Windholz O, Grohé C. Rapid modulation of L-type calcium current by acutely applied oestrogens in isolated cardiac myocytes from human, guinea-pig and rat. Exp Physiol 83: 305–321, 1998. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrissy S, Xu B, Aguilar D, Zhang J, Chen QM. Inhibition of apoptosis by progesterone in cardiomyocytes. Aging Cell 9: 799–809, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy E. Estrogen signaling and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 109: 687–696, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.236687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura H, Kurokawa J, Bai CX, Asada K, Xu J, Oren RV, Zhu ZI, Clancy CE, Isobe M, Furukawa T. Progesterone regulates cardiac repolarization through a nongenomic pathway: an in vitro patch-clamp and computational modeling study. Circulation 116: 2913–2922, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.702407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nilsson SE, Fransson E, Brismar K. Relationship between serum progesterone concentrations and cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mortality in elderly Swedish men and women: An 8-year prospective study. Gend Med 6: 433–443, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parks RJ, Howlett SE. Sex differences in mechanisms of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Pflugers Arch 465: 747–763, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1233-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patton C, Thompson S, Epel D. Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium 35: 427–431, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pergola C, Schaible AM, Nikels F, Dodt G, Northoff H, Werz O. Progesterone rapidly down-regulates the biosynthesis of 5-lipoxygenase products in human primary monocytes. Pharmacol Res 94: 42–50, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pollesello P, Papp Z, Papp JG. Calcium sensitizers: what have we learned over the last 25 years? Int J Cardiol 203: 543–548, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prendergast BJ, Onishi KG, Zucker I. Female mice liberated for inclusion in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 40: 1–5, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quadros PS, Wagner CK. Regulation of progesterone receptor expression by estradiol is dependent on age, sex and region in the rat brain. Endocrinology 149: 3054–3061, 2008. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 125: e2–e220, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rubin B, Salter WT. The effects of progesterone and some related steroids on the contraction of isolated myocardium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 105: 443–449, 1952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sadayappan S, Gulick J, Osinska H, Barefield D, Cuello F, Avkiran M, Lasko VM, Lorenz JN, Maillet M, Martin JL, Brown JH, Bers DM, Molkentin JD, James J, Robbins J. A critical function for Ser-282 in cardiac myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation and cardiac function. Circ Res 109: 141–150, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.242560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shutt RH, Howlett SE. Hypothermia increases the gain of excitation-contraction coupling in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C692–C700, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh M, Su C, Ng S. Non-genomic mechanisms of progesterone action in the brain. Front Neurosci 7: 159, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Walker JW, Moss RL. Differential roles of cardiac myosin-binding protein C and cardiac troponin I in the myofibrillar force responses to protein kinase A phosphorylation. Circ Res 101: 503–511, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Torres-Flores V, Hernández-Rueda YL, Neri-Vidaurri PC, Jiménez-Trejo F, Calderón-Salinas V, Molina-Guarneros JA, González-Martínez MT. Activation of protein kinase A stimulates the progesterone-induced calcium influx in human sperm exposed to the phosphodiesterase inhibitor papaverine. J Androl 29: 549–557, 2008. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.004614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vered Z, Poler SM, Gibson P, Wlody D, Pérez JE. Noninvasive detection of the morphologic and hemodynamic changes during normal pregnancy. Clin Cardiol 14: 327–334, 1991. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960140409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vitale C, Mendelsohn ME, Rosano GM. Gender differences in the cardiovascular effect of sex hormones. Nat Rev Cardiol 6: 532–542, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang C, Liu Y, Cao JM. G protein-coupled receptors: extranuclear mediators for the non-genomic actions of steroids. Int J Mol Sci 15: 15412–15425, 2014. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wirth MM, Meier EA, Fredrickson BL, Schultheiss OC. Relationship between salivary cortisol and progesterone levels in humans. Biol Psychol 74: 104–107, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang F, Aiello DL, Pyle WG. Cardiac myofilament regulation by protein phosphatase type 1alpha and CapZ. Biochem Cell Biol 86: 70–78, 2008. doi: 10.1139/O07-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yarnoz MJ, Curtis AB. More reasons why men and women are not the same (gender differences in electrophysiology and arrhythmias). Am J Cardiol 101: 1291–1296, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Hao YC, Song LL, Guo SM, Gu SZ, Lu SG. Effects of sex hormones on action potential and contraction of guinea pig papillary muscle. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao 19: 248–250, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]