Abstract

Composite pheochromocytoma (cPC) is extremely rare, arising in the adrenal medulla as a mixture of PC and other tumors of neural origin. We herein report on a case of adrenal incidentaloma post-operatively diagnosed as cPC with ganglioneuroblastoma (GNBL). The PC component had 7 points on the PASS, a Ki-67 index of 5.1%, a focal absence of sustentacular cells, and no genetic aberrations in succinate dehydrogenase subunit B. The GNBL component exhibited no N-myc amplification. Tumor cells of both components were stained positively for extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 and ankyrin repeat domain 1. The aberrant activation of growth signaling may play a role in the marginal malignancy of cPC.

Keywords: adrenal, composite pheochromocytoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5, ankyrin repeat domain 1

Introduction

Composite pheochromocytoma (PC) is a rare neoplasm that typically arises in the adrenal medulla as a mixture of PC and other tumors of neural origin, including peripheral neuroblastic tumors, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and neuroendocrine carcinomas (1, 2). The frequency of composite PCs in the adrenal gland has been estimated to be <10% of the total number of adrenal PCs (3, 4). To the best of our knowledge, approximately 75 adrenal (1, 2, 5-15) and 12 extra-adrenal (16-24) cases have been reported in the medical literature to date.

Peripheral neuroblastic tumors encompass a wide spectrum of differentiation and malignancy potentials from “the most primitive and malignant” neuroblastomas (NBLs) to “the most mature and benign” ganglioneuromas (GNs). Ganglioneuroblastomas (GNBLs) are an intermediate stage of neuroblastic tumors (25, 26). GNs coexist most frequently in 72.6% and 92.9% of adrenal (1, 2, 5-15) and extra-adrenal (16-24) composite PCs, respectively. However, other types of composite PCs are extremely rare, with only a few cases having been reported for adrenal PC-GNBLs (2, 25, 27-37).

Very recently, we revealed for the first time that extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) together with ankyrin repeat domain 1 (ankrd1) induced by ERK5 regulates tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) activity and catecholamine biosynthesis during neural differentiation, with ERK5 expression levels correlated with TH levels in the normal adrenal medulla (38). However, ERK5 was down-regulated, and the ERK5-mediated regulation of the cellular function was disrupted in human adrenal PC (38).

Following our review of the previous literature, we herein report on a rare case of adrenal incidentaloma in a normotensive patient who was diagnosed post-operatively with a composite PC, occurring together with a GNBL component from the right adrenal medulla on microscopic findings. In addition, we also immunohistochemically investigate the ERK5 regulation in composite adrenal PC-GNBL.

Case Report

Clinical course

A 55-year-old Japanese woman who was receiving medication for hyperlipidemia at the discretion of an office physician had a right adrenal tumor (18 mm in diameter) that was detected incidentally by plain computed tomography (CT) imaging of the chest during the examination of a lung bulla. Despite the physician's recommendation, the patient failed to attend further check-ups of the adrenal tumor, as she experienced no further symptoms and had a tight business schedule.

Five years later, at 60 years of age, the right adrenal tumor had increased in diameter to 30 mm on a follow-up CT scan when the patient was referred to our hospital for further evaluation of the adrenal mass. The patient had not complained of sudden headaches, palpitations or sweating and had no history of hypertension, constipation, or diarrhea. Here comorbidities included hyperlipidemia and pulmonary emphysema resulting from a smoking habit of 24 years. The patient's medical history included rheumatic fever in her childhood and subacute thyroiditis at the age of 40. No family history of inherited genetic syndromes (e.g., multiple endocrine neoplasms, neurofibromatosis or von Hippel-Lindau disease) was reported.

A physical examination showed the patient's height, weight, blood pressure, and heart rate to be 154.5 cm, 59.0 kg, 138/84 mmHg, and a regular 82 beats/min, respectively. Her blood cell counts, biochemical data, and urinalysis findings were all within the reference limits, except for an overproduction of catecholamine (Table 1). The 24-hour urinary excretion of adrenaline (96.8 μg/d), dopamine (1,269.5 μg/d), metanephrine (1.2 mg/d), and normetanephrine (0.54 mg/d) was increased. Blood noradrenaline levels (1.05 ng/mL) and urinary noradrenaline (181.1 μg/d) were slightly above the upper reference limit.

Table 1.

Catecholamines and Their Metabolites.

| Specimens | Concentrations | Reference ranges | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | adrenaline | 0.18 | ng/mL | 0 | - | 0.10 | ng/mL | |

| noradrenaline | 1.05 | ng/mL | 0.06 | - | 0.46 | ng/mL | ||

| dopamine | 0.05 | ng/mL | 0 | - | 0.02 | ng/mL | ||

| 24 h-urine | adrenaline | 96.8 | μg/d | 3.4 | - | 26.9 | μg/d | |

| noradrenaline | 181.1 | μg/d | 48.6 | - | 168.4 | μg/d | ||

| dopamine | 1,269.5 | μg/d | 65.0 | - | 961.5 | μg/d | ||

| metanephrine | 1.2 | mg/d | 0.04 | - | 0.19 | mg/d | ||

| normetanephrine | 0.54 | mg/d | 0.09 | - | 0.33 | mg/d | ||

| vanilylmandelic acid | 4.71 | mg/d | 2.2 | - | 6.0 | mg/d | ||

| homovanillic acid | 4.92 | mg/d | 1.5 | - | 4.9 | mg/d | ||

Noncontrast CT clearly demonstrated a mass of a heterogeneous nature within the right adrenal gland. The tumor was strongly and inhomogeneously enhanced with contrast medium on CT. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the tumor revealed low and high signal intensities on T1- and T2-weighted images, respectively. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted imaging of the abdominal MRI demonstrated the presence of an irregularly shaped low-signal-intensity region within the tumor, partially surrounded by well-enhanced regions with clear demarcation (Fig. 1). Scintigraphy of the tumor revealed strong accumulations of 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine. The patient was diagnosed clinically with a right adrenal PC and underwent laparoscopic right adrenalectomy (operation time: 2 hours 55 minutes, blood loss: 5 mL). The intra-operative and post-operative course was uneventful, with no abnormal fluctuations in blood pressure or heart rate. Adjuvant treatment was not administered, and no tumor recurrence was detected 17 months after surgery.

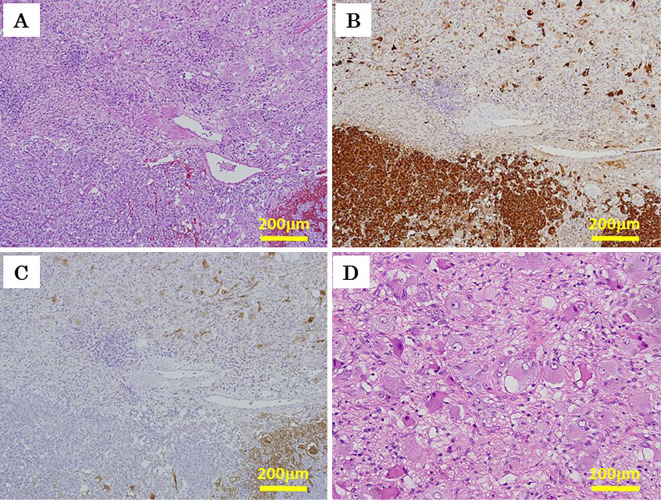

Figure 1.

The clinicopathological appearance of the adrenal composite pheochromocytoma. Computed tomography revealed a right adrenal tumor which had a heterogeneous internal structure on a plain image (A) and was inhomogeneously enhanced with contrast medium (B). The tumor exhibited high signal intensities on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (C). On gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted imaging, the tumor also presented as an irregular-shaped low-signal-intensity area partially surrounded by strongly enhanced outer regions (D). On gross appearance, the cut surface of the resected tumor consisted of two different components: a brown component in the central region and a whitish component at the periphery (E), consistent with radiological images (A-D). Similarly, the two components were readily discernable on the tumor sections prepared for microscopic observation using Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (F). Of note, panel F was synthesized intentionally by combining two photos of different pathological preparations with reference to the tumor morphology in panels A-E.

Pathological findings

On gross appearance, the cut surface of the resected specimen exhibited a heterogeneous, irregularly lobulated, dark-brownish area in the central region that was accompanied by focal hemorrhage. Distinct solid and white regions dominated the periphery outside the brown-colored area in the central tumor (Fig. 1). The morphology of the cut section was consistent with the T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI findings observed before surgical resection (Fig. 1).

Microscopically, the tumor consisted of two different components: PC and GNBL (Fig. 2A-C). The PC component was located within the dark, inhomogeneous region of the central tumor, while the GNBL component existed outside of the PC region at the periphery of the tumor (Fig. 1D and E). The PC component demonstrated histological features typical of PC, consisting of polygonal tumor cells with granular and basophilic cytoplasm, round-to-oval nuclei, and a single prominent nucleolus, distributed in well-separated nests with thin stroma and rich vascularity (Zellballen pattern) (Figure 2A, 3A and the inset).

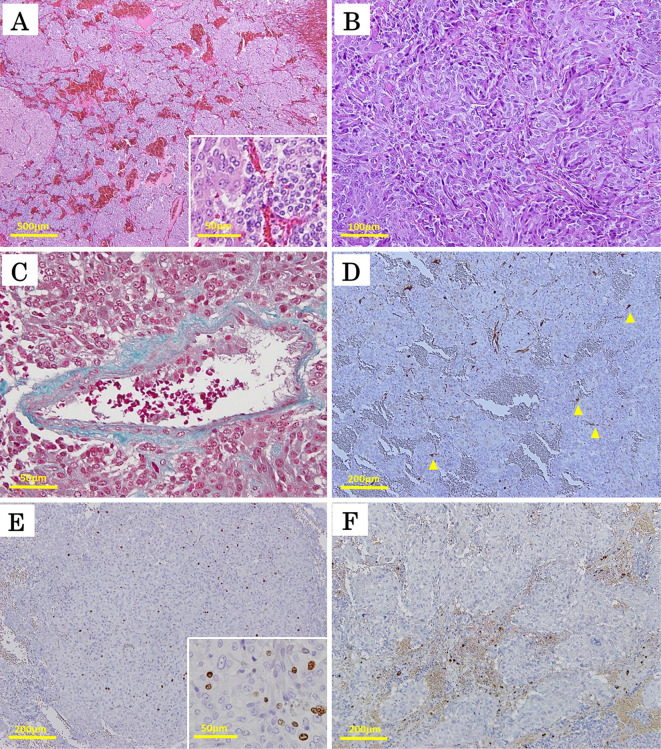

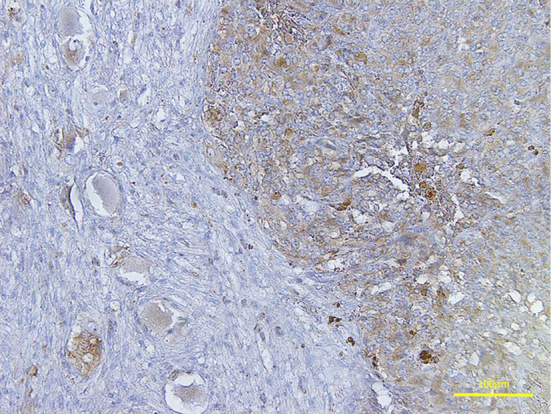

Figure 2.

Pathological microphotographs of the right adrenal composite pheochromocytoma with ganglioneuroblastoma. Different sections at the same position of the tumor were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (A) and for chromogranin A (B) and S-100 protein (C). The upper and lower halves of panels A to C represent the ganglioneuroblastoma and pheochromocytoma components of the tumor, respectively. In panel D, the GNBL component comprised a mixture of ganglion-like cells in a neurofibrillary background with no primitive neuroblastic foci, presenting with a characteristic morphology of GNBL-intermixed according to the international neuroblastoma pathology classification (original magnification 100× for A, B, and C, 200× for D).

Figure 3.

The microscopic features of the pheochromocytoma (PC) component of the right adrenal composite PC. Focal hemorrhaging was observed in the PC component, but no confluent necrosis or mitosis was observed on Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining (A). The PC component comprised two types of tumor cells: large polygonal eosinophilic cells with pleomorphic nuclei and occasionally prominent nucleoli and coarse chromaffin (left half of inset A); and small, round chromaffin cells (right half of inset A). Both types of cells were distributed in the form of variably sized nests, called Zellballen structures (A). There were also sheet-like areas and spindle cell arrangements on H&E staining (B). Although high cellularity, cellular monotony, and tumor cell spindling were noted, neither mitosis nor necrosis was evident (A, B). There was focal vascular invasion in the PC component on Elastica-Masson’s staining (C). The sustentacular cells, stained positively for S-100, partially disappeared in the PC region where the Zellballen structures were poorly aligned (D). In (D), the arrowheads indicate the sparse localization of the sustentacular cells around the disordered Zellballen nests. The PC cells were positive for the Ki-67 antigen at a maximum of 5.1% (E and the inset) but did not show any expression of vasoactive intestinal peptide (F) (original magnification 4× for A, 200× for B, 400× for C, and 100× for D-F; the insets of A and E were originally magnified at 400×).

Our immunohistochemical analyses demonstrated that the PC component stained diffusely positive for chromogranin A (Fig. 2B) and synaptophysin (Supplementary file 1) in the tumor cells and stained positive for S-100 protein (Figure 2C, 3D) in the surrounding sustentacular cells. The tumor cells proliferated in diffuse patterns and invaded neighboring blood vessels (Fig. 3C). Disappearance of the sustentacular cells was partially observed in the PC region (Fig. 3D). The Ki-67 proliferative index was noted to be at 5.1% in the highest of the PC regions (Fig. 3E and the inset). High cellularity, cellular monotony, and tumor cell spindling were also observed (Fig. 3B), although mitotic figures and necrosis were absent (Fig. 3A). These findings suggested a malignant potential, yielding a Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) of 7 points (39). In the present case, the PC component was found not to express vasoactive intestinal peptide (Fig. 3F) but was, however, positively immunostained for antibodies against succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB), suggesting a sporadic nature with no mutations in the SDHB gene (Fig. 4).

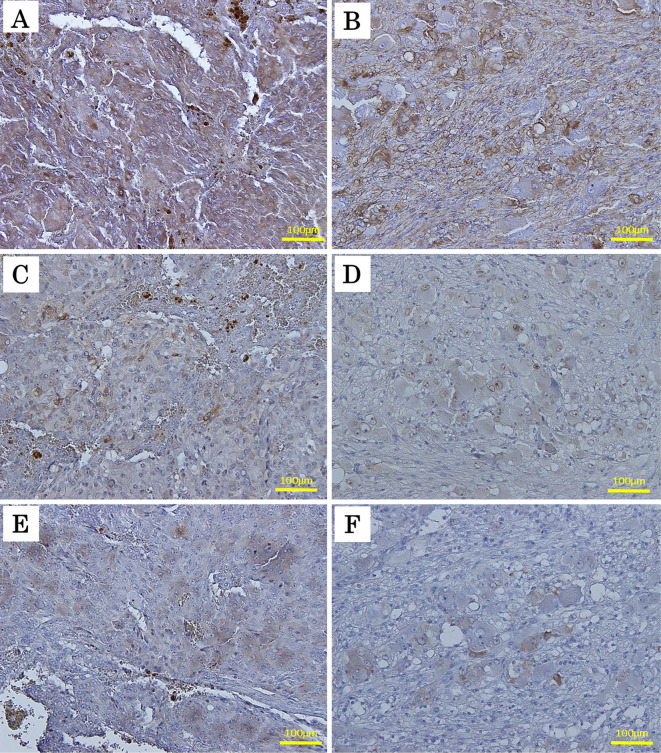

Figure 4.

The succinate dehydrogenase subunit B immunohistochemical analysis of the adrenal composite pheochromocytoma (PC). The two components constituting the adrenal composite PC expressed succinate dehydrogenase subunit B as detected by immunohistochemistry. The right half of the image represents the PC component, while the left half represents the ganglioneuroblastoma component of the composite PC (original magnification 200×).

In contrast, the GNBL component comprised a mixture of variably differentiated neuroblastic cells and ganglion-like cells in a neurofibrillary background, with no primitive neuroblastic foci (Fig. 2A and D). The GNBL component stained positively for anti-S-100 protein (Fig. 2C), neurofilament, and synaptophysin antibodies (Supplementary file 1), presenting with a characteristic morphology of GNBL-intermixed, according to the international neuroblastoma pathology classification (26).

Fig. 5 shows the immunohistochemical expression of TH, ERK5, and ankrd1 protein in both PC and GNBL components in the composite adrenal tumor. TH, a key enzyme which produces catecholamines, was expressed diffusely in the PC and neuroblastic cells. However, ERK5- and ankrd1-positive tumor cells were scattered over both of the components in the composite tumor. These findings were consistent with our recent findings regarding human adrenal PC (38), suggesting that TH may be regulated not only by an ERK5/ankrd1 signaling cascade but also aberrantly by other unknown mechanisms.

Figure 5.

The immunohistochemical findings for thyrosine hydroxylase (TH), extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5), and ankyrin repeat domain 1 (ankrd1) protein in the pheochromocytoma (PC) and ganglioneuroblastoma (GNBL) components in the composite adrenal tumor. Both the PC and GNBL components diffusely expressed TH (A and B, respectively), but parts of the tumor cells had positive staining for anti-ERK5 (C and D, respectively) and ankrd1 (E and F, respectively) antibodies in both components (original magnification 200×).

The immunohistochemical staining methods (38, 40) and fluorescence in-situ hybridization analyses used in the present report are described in detail in the supplementary file (Supplementary file 2).

Experimental protocols for immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in-situ hybridization.

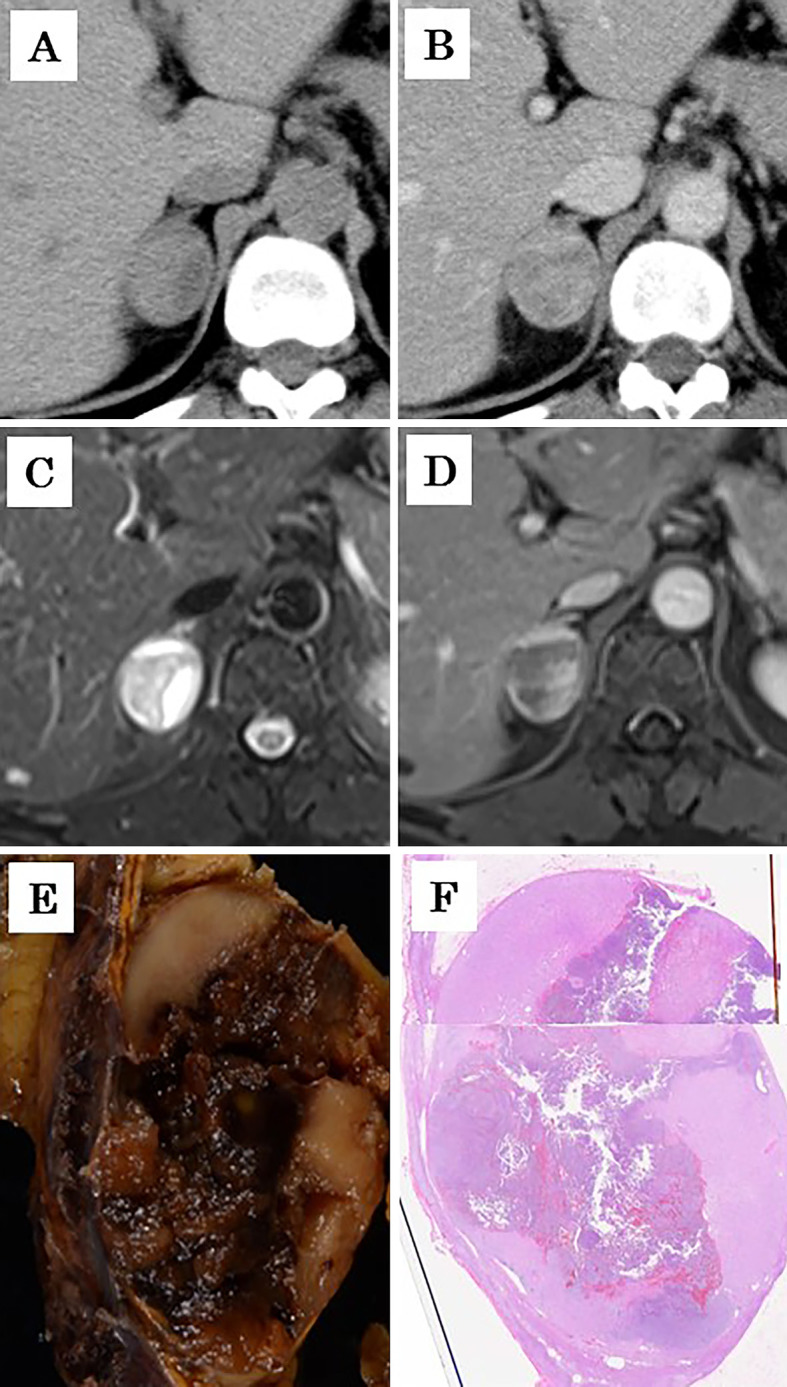

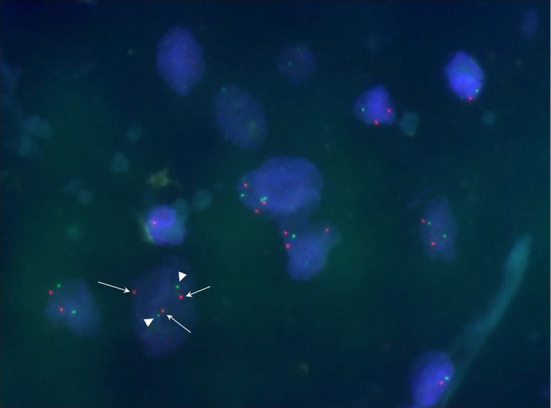

Cytogenic analysis of the N-myc gene in ganglioneuroblastomas using fluorescence in-situ hybridization

N-myc gene status was evaluated via interphase fluorescence in-situ hybridization in 3-μm-thick tissue sections from a paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed surgically resected clinical specimen, using previously described experimental protocols [ (41) and Supplementary file 2]. Fluorescence in-situ hybridization signals were scored in 200 non-overlapping tumor nuclei. In the present case (Fig. 6), diploidy patterns [2 N-myc and 2 centrosomal protein 2 (CEP2) signals] were identified in 169 tumor cells (84.5%). A further 5 cells (2.5%) exhibited 0 to 1 N-myc and 2 CEP2 signals, and 21 cells (10.5%) displayed a hyperploidy pattern (3 to 5 N-myc and 3 to 5 CEP2 signals) in the nuclei. Copy number gain of the N-myc gene, 1 copy greater than the CEP2 probe signals (3 N-myc and 2 CEP2 signals), was detected in 5 GNBL cells (2.5%) (Fig. 6, arrows and arrow heads). None of the tumor cells demonstrated N-myc amplification (at least 10 copies greater than the CEP2 gene).

Figure 6.

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization image of ganglioneuroblastoma cells displaying gain of N-myc gene copies. The fluorescence in-situ hybridization signals were scored in 200 non-overlapping tumor nuclei. Red and green fluorescence signals indicated N-myc and centrosomal protein 2 (CEP2) gene copies, respectively. Tumor nuclei were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Normal ploidy patterns (2 N-myc and 2 CEP2 signals) were detected in 169 tumor cells (84.5%). In 5 cells (2.5%), the number of N-myc signals (arrows) was 1 copy greater than the CEP2 probe signals (3 N-myc and 2 CEP2 signals, arrow heads). A further 5 cells (2.5%) displayed 0 to 1 N-myc and 2 CEP2 signals, and 21 cells (10.5%) exhibited a polyploidy pattern (3 to 5 N-myc and 3 to 5 CEP2 signals) in the nuclei (original magnification 1,000×).

Discussion

Composite PCs are exceedingly rare tumors - particularly composite PC-GNBL tumors, where fewer than 20 cases (2, 25, 27-36), including the present, having been reported in the medical literature to date (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reported Cases of Composite Pheochromocytoma (PC) with Ganglioneuroblastoma (GNBL).

| Case | References | Age (years) | Sex | Location | Affected side | Genetic disorder | Hyper-tension | N-myc status in GNBL | DNA ploidy pattern in GNBL | Malignancy | Metastasis | Follow-up | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 | 42 | F | adrenal | ND | - | - | - | alive | ||||

| 2 | 27 | 14 | F | adrenal | Rt | NF type-1 | - | NA | NA | malignant PC | liver, lung, lymph nodes and bones | 6 mo | dead |

| 3 | 29 | 43 | M | adrenal | Rt | - | - | NA | NA | PC + GN (primary) malignant PC + GNBL (reccurence) | liver | 10 yrs | dead |

| 4 | 30 | 25 | M | adrenal | Rt | - | Yes | NA | NA | - | - | ND | alive |

| 5 | 31 | 63 | F | adrenal | Rt | - | Yes | NA | NA | malignant PC | liver | 5 mo | dead |

| 6 | 32 | 21 | F | retroperitoneal | ND | - | Yes | NA | NA | - | - | ND | alive |

| 7 | 33 | 35 | M | adrenal | Rt | NF type-1 | Yes | NA | NA | - | - | ND | ND |

| 8 | 33 | 42 | M | adrenal | Lt | - | Yes | NA | NA | - | - | ND | ND |

| 9 | 34 | 49 | M | adrenal | Lt | MEN 2A | Yes | NA | NA | thyroid medullary carcinoma | - | - | dead |

| 10 | 35 | 29 | F | adrenal | Lt | - | Yes | NA | NA | - | - | 5 yrs | alive |

| 11 | 36 | 55 | F | adrenal | Rt | - | - | NA | NA | - | - | 11 mo | alive |

| 12 | 37 | 73 | M | adrenal | Lt | - | - | NA | NA | lung SCC | lung SCC metastasis to the left adrenal | ND | ND |

| 13 | 2 | 15 | M | ND | Rt | - | Yes | no amp. | NA | - | - | ND | alive |

| 14 | 25 | 9 | F | adrenal | Rt | - | Yes | no amp. | diploidy | - | - | 18 mo | alive |

| 15 | Current case | 60 | F | adrenal | Rt | - | - | no amp. | hyperploidy | - | - | 6.5 yrs* | alive |

Abbreviations: amp: amplification, F: female, GN: ganglioneuroma, GNBL: ganglioneuroblastoma, Lt: left, M: male, MEN: multiple endocrine neoplasm, mo: months, NA: not accessed, ND: not described, NF: neurofibromatosis, PC: pheochromocytoma, Rt: right, SCC: squamous cell carcinoma, yrs: years, - : no

*: Follow-up duration after initial presentation (19 months since surgical resection).

Shawa et al. (6) described how composite PCs could not be distinguished from pure PCs based on clinical presentations, biochemical data, and CT images alone, owing to similar symptomatology, biochemical results, morphology, and attenuation values. Additionally, no reports on the differential radiographic features between composite and pure PCs have been published. Although up to 70% of PCs present with high signal intensities on T2-weighted MRI (designated as the light bulb sign), at least 30% of PCs exhibit moderate or low T2-weighted signal intensities on MRI and appear similar to other adrenal diseases (42). The findings on ultrasonography, CT scans, MRI, 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy, and positron emission tomography complement each other with respect to differentiating PCs from other adrenal diseases in clinical practice (42-44). Furthermore, it is also impossible to clinically differentiate between NBLs, GNBLs, and GNs, owing to variable appearances on imaging analyses; although GNs tend to be more homogeneous (45). Most case reports on composite PCs have determined a diagnosis based on the post-operative histopathological observations (1), except for two cases in which the authors performed pre-operative and intra-operative biopsies (46, 47). Thus, we believe that it is not possible to predict clearly whether PCs are pure or composite or to determine what neural elements would be combined with PCs if pathological exploration was not completed.

It is widely accepted that the biological behavior of PCs cannot be predicted on the basis of histopathological features alone (39). The diagnosis of a malignant PC can be determined by the presence of recurrence or a metastatic lesion at a site where chromaffin cells are not normally present (4). Although around 10% of pure PCs have been considered malignant, many more cases may become metastatic over the long duration of follow-up after the initial diagnosis. Recently, Ayala-Ramirez et al. (48) demonstrated that 25% and 60% of 267 and 104 patients with adrenal and extra-adrenal PCs had metastatic diseases, with an overall survival of 20.64 or 9.49-years, respectively. As for composite PCs, Khan et al. (1) documented that approximately 25% of total composite PCs had metastasized during the observation period. Composite PCs can metastasize from either the sympathetic or the neural components, both of which are generally thought to be derived from common chromaffin precursor cells by aberrant differentiation (1). Metastatic elements of composite PCs from its primary site vary on a case by case basis. Some involve PC cells (3, 6), while others are neural (15, 20, 27) or involve both components (49).

Among the neural elements in composite PCs, neuroblastic tumors coexist most frequently. Generally, neuroblastic tumors can be classified into three pathological disease conditions according to the extent of differentiation, as NBLs, GNBLs, or GNs if the tumors are poorly, intermediately, or well-differentiated, respectively. NBLs are malignant tumors consisting of primitive neuroblasts that may arise anywhere within the sympathetic plexus or adrenal medulla (50). NBLs are considered more aggressive than GNs, which usually behave in a benign fashion (50). GNBLs belong to an intermediate group between NBLs and GNs, both in terms of maturation and malignancy potential (45). NBLs and GNBLs are typically pediatric diseases (26, 50).

The prognosis of patients diagnosed with neuroblastic tumors is dependent on factors such as age at diagnosis, tumor grading and stage, N-myc amplification status, and deletion of chromosome 1p (26, 51). In approximately 20% of NBLs the human proto-oncogene N-myc is amplified, the presence of which is generally indicative of a poor prognosis for NBLs (2, 26). N-myc amplification was found to occur only in around 2% to 3.1% and 0% of 32 GNBLs and 10 GNs, respectively (41, 52). In contrast, adult-onset NBLs and GNBLs are extremely rare, with fewer than 100 cases of these tumors having been reported in adults in the English medical literature to date (53, 54). In comparison to pediatric cases, N-myc is less frequently amplified in adult-onset cases (53). In several recent reviews (53, 54), between 35% and 50% of adult-onset cases have reportedly presented with metastases at diagnosis, seemingly suggesting a relatively poor oncological outcome. At present, however, the tumor biology and clinical prognoses remain unclear, due to disease rarity, and so treatment guidelines on adult-onset NBLs or GNBLs have not yet been established, with clinical practice regimens only able to be extrapolated from the pediatric guidelines (26, 53, 54).

Khan et al. (1) described distant metastasis as having occurred in 1 of 30 adrenal composite PC-GN tumors and 9 of 11 cases with adrenal composite PC mixed with an NBL, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, or neuroendocrine carcinoma. These findings suggest that the tumor behavior and prognosis of composite PCs are greatly influenced by the type of neural components involved. According to Wang et al. (40), copy number gain (1 to 9 copies more than CEP2 gene) and amplification (at least 10 copies greater than those) of the N-myc gene were observed in 78.1% and 3.1% of 32 patients with GNBLs and NBLs, respectively. They also demonstrated that N-myc gain was a favorable prognostic factor in 220 pediatric patients with neuroblastic tumors, compared with a normal and amplified status of the N-myc gene. In addition, hyperploidy was also found to be associated with a favorable prognosis in neuroblastic tumors (55, 56). In the present case, the gene status of N-myc in the GNBL component was not amplified but gained. Furthermore, 10.5% of GNBL cells presented with hyperploidy. These findings support the benign nature of the neuroblastic component of the present composite PC. To the best of our knowledge, the presence of amplified N-myc has not yet been confirmed in the neural elements of composite PCs (2, 20). Comstock et al. (2) have insisted that composite PCs should be regarded as a histological variant of pure PCs rather than a separate disease entity.

Strong et al. (4) reported that all malignant PCs had a PASS ≥6 points and recommended that patients with a PASS ≥4 points should be monitored closely for recurrence. de Wailly et al. (57) recently suggested the presence of tumor necrosis, a Ki-67 proliferative index of >4%, and the absence of S-100 protein as new criteria for recurrence and a high risk of malignancy. It has also been revealed that the incidence of malignancy in PCs is much greater with SDHB mutations than without (58). A deletion of the SDHB gene has recently been associated with composite paraganglioma with NBL (59). In the present case, the PC component was stained positively for SDHB but had histological features consistent with a PASS of 7 points, a Ki-67 proliferative index of 5.1%, and the focal absence of sustentacular cells staining positive for S-100 protein on immunohistochemical analysis. These findings suggested that the PC component of the present case of composite PC might be malignant but lacking any clinically detectable metastases at the current stage.

In our previous report (37), ERK5 participated in neuronal growth and catecholamine biosynthesis, and ankrd1, a target molecule of ERK5, regulated TH in an ERK5-dependent manner. Unlike normal chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla, ERK5 regulation of catecholamine levels is disrupted in human PCs (37), which may be because some cases of PC show few sympathetic symptoms associated with catecholamine overproduction while others behave marginally in malignancy, as a consequence of the aberrant role of ERK5 in tumor biology. Further follow-up of the present case and examination of more cases of composite PCs is therefore necessary to clarify whether the tumor itself is benign or malignant.

We herein reported on a very rare case of adrenal composite PC concomitant with GNBL that was incidentally detected and clinically asymptomatic, despite catecholamine overproduction, and had not been metastatic or recurrent in the approximate 6.5 years since initial diagnosis. The PC component of the tumor demonstrated pathological characteristics consistent with a PASS of 7 points, a maximum Ki-67 proliferative index of 5.1%, the focal absence of sustentacular cells, and a lack of any genetic aberration in the SDHB gene. The GNBL component of the tumor showed DNA hyperploidy but no amplification of N-myc. Tumor cells of the PC and GNBL components expressed ERK5 and ankrd1 protein variably cell by cell, inconsistent with diffuse expression of TH, a key enzyme which produces catecholamines. These findings suggest that the ERK5/ankrd1 signaling cascade may aberrantly play more roles in tumor growth in composite PCs than in the normal adrenal medulla. Our findings support the potentially malignant nature of the PC component in the present case of composite PC-GNBL. However, further long-term follow-up and large-scale studies of this rare disease will be needed to more definitively evaluate the oncological outcome.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report, any accompanying images, the clinical data, and the results of the tumor genetics analyses. A copy of the written consent form is available for review by the editor of this journal.

The present study was performed in accordance with the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine (H25-98 and H27-122).

The adrenal composite pheochromocytoma expressed neurofilament and synaptophysin.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 15K07963 to Y.O), and Takeda Science Foundation (Y.O). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

We greatly appreciate the excellent technical support of Dr. Naing Ye Aung from the Institute for Promotion of Medical Science Research at Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine. We thank assistant professors Atsushi Yamagishi, Tomohiro Shibasaki and Hisashi Kawazoe from the Department of Urology at Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine for their clinical cooperation. We also thank Kumiko Hayashi and Takeshi Nakamura from Chromosome Analysis Group, Molecular Genetic Analysis Department, LSI Medience Corporation (Tokyo, Japan) for their technical support on N-myc gene fluorescence in-situ hybridization analysis.

References

- 1.Khan AN, Solomon SS, Childress RD. Composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma: a rare experiment of nature. Endocr Pract 16: 291-299, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comstock JM, Willmore-Payne C, Holden JA, Coffin CM. Composite pheochromocytoma: a clinicopathologic and molecular comparison with ordinary pheochromocytoma and neuroblastoma. Am J Clin Pathol 132: 69-73, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam KY, Lo CY. Composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma of the adrenal gland: an uncommon entity with distinctive clinicopathologic features. Endocr Pathol 10: 343-352, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strong VE, Kennedy T, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. Prognostic indicators of malignancy in adrenal pheochromocytomas: clinical, histopathologic, and cell cycle/apoptosis gene expression analysis. Surgery 143: 759-768, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahajan H, Lee D, Sharma R, et al. Composite phaeochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma, an uncommon entity: report of two cases. Pathology 42: 295-298, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shawa H, Elsayes KM, Javadi S, Sircar K, Jimenez C, Habra MA. Clinical and radiologic features of pheochromocytoma/ganglioneuroma composite tumors: a case series with comparative analysis. Endocr Pract 20: 864-869, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon S, Mahajan P, Desai SB. Composite adrenal medullary tumor: a rare cause of hypertension in a young male. Urol Ann 3: 36-38, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau SK, Chu PG, Weiss LM. Mixed cortical adenoma and composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma: an unusual corticomedullary tumor of the adrenal gland. Ann Diagn Pathol 15: 185-189, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franquemont DW, Mills SE, Lack EE. Immunohistochemical detection of neuroblastomatous foci in composite adrenal pheochromocytoma-neuroblastoma. Am J Clin Pathol 102: 163-170, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta G, Saran RK, Godhi S, Srivastava S, Saluja SS, Mishra PK. Composite pheochromocytoma masquerading as solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of pancreas. World J Clin Cases 3: 474-478, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steen O, Fernando J, Ramsay J, Prebtani APH. An unusual case of a composite pheochromocytoma with neuroblastoma. J Endocrinol Metab 4: 39-46, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royer N, Miron J, Kirby P, Weigel RJ, Lal G. Incidental finding of composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma: successful management after emergent appendectomy and review of the literature - case reports. World J Endocr Surg 3: 39-44, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura N, Watanabe T, Fukase M, Wakita A, Noshiro T, Kimura I. Neurofibromin and NF1 gene analysis in composite pheochromocytoma and tumors associated with von Recklinghausen's disease. Mod Pathol 15: 183-188, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao RN, Singla N, Yadav K. Composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma of the adrenal gland: a case report with immunohistochemical study. Urol Ann 5: 115-118, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kikuchi Y, Wada R, Sakihara S, Suda T, Yagihashi S. Pheochromocytoma with histologic transformation to composite type, complicated by watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and achlorhydria syndrome. Endocr Pract 18: e91-e96, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J, Wu J, Cai L, et al. Retroperitoneal composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma: a case report and review of literature. Diagn Pathol 8: 63, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CH, Boag AH, Beiko DT, Siemens DR, Froese A, Isotalo PA. Composite paraganglioma-ganglioneuroma of the urinary bladder: a rare neoplasm causing hemodynamic crisis at tumour resection. Can Urol Assoc J 3: E45-E48, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong J, Wang X, Chen X, et al. Adrenal and extra-adrenal nonfunctioning composite pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma with immunohistochemical ectopic hormone expression: comparison of two cases. Urol Int 85: 368-372, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirasaki S, Kanzaki H, Okuda M, Suzuki S, Fukuhara T, Hanaoka T. Composite paraganglioma-ganglioneuroma in the retroperitoneum. World J Surg Oncol 7: 81-81, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritzsche FR, Bode PK, Koch S, Frauenfelder T. Radiological and pathological findings of a metastatic composite paraganglioma with neuroblastoma in a man: a case report. J Med Case Rep 4: 374, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tohme CA, Mattar WE, Ghorra CS. Extra-adrenal composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma. Saudi Med J 27: 1594-1597, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshimi N, Tanaka T, Hara A, Bunai Y, Kato K, Mori H. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma. A case report. Pathol Res Pract 188: 1098-1100; discussion 1101-1103, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Montpréville VT, Mussot S, Gharbi N, Dartevelle P, Dulmet E. Paraganglioma with ganglioneuromatous component located in the posterior mediastinum. Ann Diagn Pathol 9: 110-114, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pytel P, Krausz T, Wollmann R, Utset MF. Ganglioneuromatous paraganglioma of the cauda equina: a pathological case study. Hum Pathol 36: 444-446, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiel EL, Trost BA, Tower RL. A composite pheochromocytoma/ganglioneuroblastoma of the adrenal gland. Pediatr Blood Cancer 54: 1032-1034, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peuchmaur M, d'Amore ES, Joshi VV, et al. Revision of the international neuroblastoma pathology classification: confirmation of favorable and unfavorable prognostic subsets in ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular. Cancer 98: 2274-2281, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakagawara A, Ikeda K, Tsuneyoshi M, Daimaru Y, Enjoji M. Malignant pheochromocytoma with ganglioneuroblastoma elements in a patient with von Recklinghausen's disease. Cancer 55: 2794-2798, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donadio F, La Ganga V, Vajo M, Campanella G, Coverlizza S. Ganglioneuroblastoma with areas of pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland. Case report. Minerva Chir 37: 551-558, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nigawara K, Suzuki T, Tazawa H, et al. A case of recurrent malignant pheochromocytoma complicated by watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, achlorhydria syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 65: 1053-1056, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tischler AS, Dayal Y, Balogh K, Cohen RB, Connolly JL, Tallberg K. The distribution of immunoreactive chromogranins, S-100 protein, and vasoactive intestinal peptide in compound tumors of the adrenal medulla. Hum Pathol 18: 909-917, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kakimoto S, Sakai H, Kondo A, Nishimori H, Itoh M, Kishikawa M. Malignant pheochromocytoma with ganglioneuroblastomatous elements: a case report. Nishinihon J Urol 50: 661-665, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimura N, Miura Y, Miura K, et al. Adrenal and retroperitoneal mixed neuroendocrine-neural tumors. Endocr Pathol 2: 139-147, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe T, Noshiro T, Kusakari T, et al. Two cases of pheochromocytoma diagnosed histopathologically as mixed neuroendocrine-neural tumor. Intern Med 34: 683-687, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matias-Guiu X, Garrastazu MT. Composite phaeochromocytoma-ganglioneuroblastoma in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIA. Histopathology 32: 281-282, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujiwara T, Kawamura M, Sasou S, Hiramori K. Results of surgery for a compound adrenal tumor consisting of pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroblastoma in an adult: 5-year follow-up. Intern Med 39: 58-62, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okumi M, Ueda T, Ichimaru N, Fujimoto N, Itoh K. [A case of composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroblastoma in the adrenal gland with primary hyperparathyroidism]. Hinyokika Kiyo 49: 269-272, 2003(in Japanese, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pathmanathan N, Murali R. Composite phaeochromocytoma with intratumoural metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Pathology 35: 263-265, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obara Y, Nagasawa R, Nemoto W, et al. ERK5 induces ankrd1 for catecholamine biosynthesis and homeostasis in adrenal medullary cells. Cell Signal 28: 177-189, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson LD. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 26: 551-566, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ichiyanagi O, Ito H, Takai S, et al. A GRIA2 and PAX8-positive renal solitary fibrous tumor with NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion. Diagn Pathol 10: 155, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M, Zhou C, Cai R, Li Y, Gong L. Copy number gain of MYCN gene is a recurrent genetic aberration and favorable prognostic factor in Chinese pediatric neuroblastoma patients. Diagn Pathol 8: 5, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leung K, Stamm M, Raja A, Low G. Pheochromocytoma: the range of appearances on ultrasound, CT, MRI, and functional imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 200: 370-378, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raja A, Leung K, Stamm M, Girgis S, Low G. Multimodality imaging findings of pheochromocytoma with associated clinical and biochemical features in 53 patients with histologically confirmed tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 201: 825-833, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lattin GE Jr, Sturgill ED, Tujo CA, et al. From the radiologic pathology archives: adrenal tumors and tumor-like conditions in the adult: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 34: 805-829, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lonergan GJ, Schwab CM, Suarez ES, Carlson CL. Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 22: 911-934, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Layfield LJ, Glasgow BJ, Du Puis MH, Bhuta S. Aspiration cytology and immunohistochemistry of a pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma of the adrenal gland. Acta Cytol 31: 33-39, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka T, Yoshimi N, Iwata H, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma of the organ of Zuckerkandl. Diagn Cytopathol 5: 64-68, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayala-Ramirez M, Feng L, Johnson MM, et al. Clinical risk factors for malignancy and overall survival in patients with pheochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas: primary tumor size and primary tumor location as prognostic indicators. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: 717-725, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Satake H, Inoue K, Kamada M, Watanabe H, Furihata M, Shuin T. Malignant composite pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland in a patient with von Recklinghausen's disease. J Urol 165: 1199-1200, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rha SE, Byun JY, Jung SE, Chun HJ, Lee HG, Lee JM. Neurogenic tumors in the abdomen: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics 23: 29-43, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spitz R, Hero B, Simon T, Berthold F. Loss in chromosome 11q identifies tumors with increased risk for metastatic relapses in localized and 4S neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 12: 3368-3373, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Angelini P, London WB, Cohn SL, et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients with ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular subtype: a report from the INRG project. Eur J Cancer 48: 1185-1191, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jrebi NY, Iqbal CW, Joliat GR, Sebo TJ, Farley DR. Review of our experience with neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma in adults. World J Surg 38: 2871-2874, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bolzacchini E, Martinelli B, Pinotti G. Adult onset of ganglioneuroblastoma of the adrenal gland: case report and review of the literature. Surg Case Rep 1: 79, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Look AT, Hayes FA, Shuster JJ, et al. Clinical relevance of tumor cell ploidy and N-myc gene amplification in childhood neuroblastoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 9: 581-591, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.George RE, London WB, Cohn SL, et al. Hyperdiploidy plus nonamplified MYCN confers a favorable prognosis in children 12 to 18 months old with disseminated neuroblastoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 23: 6466-6473, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Wailly P, Oragano L, Rade F, et al. Malignant pheochromocytoma: new malignancy criteria. Langenbecks Arch Surg 397: 239-246, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shuch B, Ricketts CJ, Metwalli AR, Pacak K, Linehan WM. The genetic basis of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: implications for management. Urology 83: 1225-1232, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Armstrong R, Greenhalgh KL, Rattenberry E, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) gene deletion associated with a composite paraganglioma/neuroblastoma. J Med Genet 46: 215-216, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental protocols for immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in-situ hybridization.

The adrenal composite pheochromocytoma expressed neurofilament and synaptophysin.