Abstract

Background

Data are conflicting regarding the possible effects of statins in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). This post hoc analysis assessed the effects of statin therapy on disease-related outcomes in IPF.

Methods

Patients randomised to placebo (n=624) in three controlled trials of pirfenidone in IPF (CAPACITY 004 and 006, ASCEND) were categorised by baseline statin use. Outcomes assessed during the 1-year follow-up included disease progression, mortality, hospitalisation and composite outcomes of death or ≥10% absolute decline in FVC and death or ≥50 m decline in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD).

Results

At baseline, 276 (44%) patients were statin users versus 348 (56%) non-users. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, except statin users were older and had higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease and risk factors. In multivariate analyses adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics, statin users had lower risks of death or 6MWD decline (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.48 to 0.99, p=0.0465), all-cause hospitalisation (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.35 to 0.94, p=0.0289), respiratory-related hospitalisation (HR 0.44; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.80, p=0.0063) and IPF-related mortality (HR 0.36; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.95, p=0.0393) versus non-users. Non-significant treatment effects favouring statin use were observed for disease progression (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.52 to 1.07, p=0.1135), all-cause mortality (HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.21, p=0.1369) and death or FVC decline (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.07, p=0.1032).

Conclusions

This post hoc analysis supports the hypothesis that statins may have a beneficial effect on clinical outcomes in IPF. Prospective clinical trials are required to validate these observations.

Trial registration numbers

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Key messages.

What is the key question?

Do statins have an effect on disease-related outcomes in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)?

What is the bottom line?

In a large and well defined cohort of patients with IPF, statins were associated with reductions in IPF-related mortality, hospitalisation and disease progression compared with patients who did not receive statins.

Why read on?

Statins are frequently prescribed for concomitant cardiovascular disease and risk factors in patients with IPF, and have previously been linked with both detrimental and beneficial actions on IPF progression.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a serious, debilitating and progressive lung disease that presents with exertional dyspnoea and cough.1–3 IPF is diagnosed more frequently among men than women, during the seventh or eighth decade of life and among current or ex-smokers.4 IPF is associated with substantial healthcare requirements and patients with IPF typically require frequent hospitalisations as a consequence of their disease.5 Furthermore, the prognosis for patients with IPF is poor and survival rates are lower than those reported for many common cancers.6 7 The 5-year survival rate for patients from the time of diagnosis is between 20% and 40%,8 with a median survival of between 2 years and 5 years.2 7

Two antifibrotic drugs are approved for the treatment of IPF, pirfenidone9 10 and nintedanib.11 Both drugs have been shown to significantly reduce the decline in FVC compared with placebo among patients with IPF.9–11 Pirfenidone has also been shown to improve survival among patients with IPF: a pooled analysis of data found a 48% reduction in mortality compared with placebo after 1 year of treatment with pirfenidone (p=0.01).9

Cardiovascular (CV) comorbidities are common in IPF12 and medications are often required to treat patients with CV risk factors. This includes the 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitor or ‘statin’ class of drugs, which are widely used for their cholesterol-lowering effects and associated reduction in the risk for CV morbidity.13 14 The potential for additional benefits from statin therapy has been investigated previously. For example, statins have been shown to attenuate the decline in pulmonary function associated with normal ageing, with the magnitude of the protective effect apparently modified by smoking status.15 Furthermore, the effect of statins on disease-related outcomes in patients with COPD has also been investigated.16 However, the relationship between statins and the development of interstitial lung disease (ILD) is controversial. Case reports and, most recently, a regression analysis of current and former smokers included in the COPDGene study suggest that statin use may be associated with the presence of interstitial lung abnormalities, at least among patients who are current or ex-smokers.17 18

In contrast, a recent analysis of a health administrative database that included 6665 individuals with possible or probable ILD and 26 660 matched control subjects, did not reveal an association between statin use and the incidence of ILD.19 Conflicting data have also emerged with regard to the effect of statins in patients with established lung disease such as IPF. Animal studies have shown that statins prevent the development of pulmonary fibrosis, although they do not appear to attenuate established pulmonary fibrosis.20 In a small retrospective analysis of data from 35 patients with IPF, no association between statin therapy and mortality was identified.21 However, a more recent analysis of data from the national Danish Patients Registry found that statin use was associated with reduced mortality among patients with ILD, including those with IPF.22

To further investigate the potential effects of statins in patients with IPF, a post hoc analysis was performed using data from the placebo arms of the pirfenidone phase III programme. The effect of statins on mortality and other clinically relevant disease-related outcomes was investigated in this well defined population of patients with IPF.

Materials and methods

This was a post hoc analysis of data from the placebo arms of three phase III, randomised, controlled, double-blind clinical trials of pirfenidone in IPF: Study 016, Assessment of Pirfenidone to Confirm Efficacy and Safety in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (ASCEND; NCT01366209);9 and Study 004 and Study 006, Clinical Studies Assessing Pirfenidone in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (CAPACITY; NCT00287729 and NCT00287716, respectively).10 Patient enrolment took place from July 2011 to January 2013, and from April 2006 to November 2008 in the ASCEND and CAPACITY trials, respectively. ASCEND and CAPACITY were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as the relevant local legal and regulatory requirements of the countries in which the trials were conducted. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to any study procedure.

Patients

ASCEND and CAPACITY recruited patients aged between 40 years and 80 years who had a confirmed diagnosis of IPF by high-resolution CT (HRCT) alone or HRCT plus surgical lung biopsy. Eligible patients had an FVC ≥50% (and ≤90% in the ASCEND trial), per cent predicted carbon monoxide diffusing capacity ≥35% (≥30% and ≤90% in the ASCEND trial) and a 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) ≥150 m with no evidence of improvement in measures of IPF disease severity over the preceding year. Patients showing significant clinical worsening of IPF as judged by the investigator, or a difference in FVC >10% between screening and day 1, were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were clinically significant concomitant disease including a history of unstable or deteriorating cardiac disease within the previous 6 months, and active infection or malignancy. Patients with a history of COPD were excluded from ASCEND, but were eligible for the CAPACITY studies if the condition had not led to hospitalisation within 6 months prior to study entry.9 10 The use of concomitant medication, including statins, was ascertained through open-ended questioning by study investigators.

Assessments

The outcomes evaluated were disease progression (defined as the first occurrence of any of the following: ≥10% absolute decline in per cent predicted FVC, a decline of at least 50 m in 6MWD (both required confirmation at two consecutive assessments at least 6 weeks apart) or death), all-cause mortality, IPF-related mortality (the cause of death was assessed by blinded clinical investigators in CAPACITY and a mortality assessment committee in ASCEND), change from baseline in FVC, change from baseline in 6MWD, all-cause hospitalisation and respiratory-related hospitalisation (defined as a hospitalisation in which the primary reason for admission was determined to be respiratory related by the investigator). The composite outcomes of all-cause mortality or a ≥10% absolute decline in per cent predicted FVC and all-cause mortality or a ≥50 m decline in 6MWD were prespecified outcomes in ASCEND.9 All outcomes were evaluated over 1 year.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population categorised by statin use at baseline, and corresponding crude (unadjusted) risks of binary study outcomes among statin users and non-users, were compared. Statistical comparisons were undertaken using an independent-samples t-test for continuous variables and a χ2 test for categorical variables.

A shared frailty model (an extension of the Cox proportional hazards model that adjusts for intracluster (ie, intratrial) correlation) was employed to examine the relationship between statin use and study outcomes without adjustment (bivariate model), and with adjustment for age, sex, smoking status, lung function, exercise tolerance, dyspnoea, medical history and CV risk factors (multivariate model). Survival analyses were based on the Kaplan-Meier estimator, and comparisons of statin users and non-users were based on the log-rank test. Only observed data were employed in analyses (ie, missing values were not imputed). Individuals were censored at the time of loss to follow-up, at the time of lung transplantation or at the end of the 1-year follow-up period, whichever occurred first. The presence of multicollinearity, hazards assumptions and treatment of death as a competing risk (where appropriate) were evaluated using published methods.23 24 SAS V.9.3 for Windows was used to evaluate the proportionality assumption for statin use using a time-dependent covariate (ie, interaction between statin and time). Models not considering death as an outcome were estimated, alternatively treating death as a competing risk rather than censoring on death.

Results

Patients

A total of 624 patients were included in this post hoc analysis (ASCEND, n=277; CAPACITY, n=347), of whom 276 (44.2%) were receiving statin therapy at baseline (simvastatin, 38.4%; atorvastatin, 34.8%; pravastatin, 9.8%; rosuvastatin, 9.4%; other, 7.6%). The mean (SD) duration of follow-up was 348.3 (58.8) days in patients who received statins and 342.7 (67.8) days in those who did not. During the 1-year follow-up, one statin user and four statin non-users received a lung transplant.

Statin users were older than non-users and a greater proportion of statin users were male (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of baseline demographics: baseline statin users and non-users

| Parameter | Statin users (N=276) | Statin non-users (N=348) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 68.2 (7.0) | 66.3 (7.8) | 0.0014 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 225 (81.5) | 240 (69.0) | 0.0004 |

| Mean % predicted FVC (SD) | 72.5 (14.0) | 71.6 (13.3) | 0.4297 |

| Mean % predicted DLco* (SD) | 45.4 (10.3) | 45.7 (11.7) | 0.7329 |

| Mean 6MWD*, m (SD) | 407.4 (89.8) | 415.3 (97.6) | 0.3028 |

| Mean UCSD-SOBQ score* (SD) | 34.3 (22.1) | 35.4 (21.2) | 0.5325 |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 127 (46.0) | 53 (15.2) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic renal failure | 13 (4.7) | 7 (2.0) | 0.0573 |

| COPD | 14 (5.1) | 8 (2.3) | 0.0621 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 234 (84.8) | 61 (17.5) | <0.0001 |

| Smoker (current/former) | 186 (67.4) | 198 (56.9) | 0.0074 |

| Hypertension | 183 (66.3) | 157 (45.1) | <0.0001 |

| Obesity† | 125 (45.3) | 140 (40.2) | 0.2041 |

| Diabetes | 75 (27.2) | 59 (17.0) | 0.0020 |

*Statin users with missing values: DLco, n=1; 6MWD, n=4; UCSD-SOBQ, n=4. Statin non-users with missing values: DLco, n=1; 6MWD, n=5; UCSD-SOBQ, n=3.

†Defined as a body mass index >30 kg/m2.

6MWD, 6-minute walk distance; DLco, carbon monoxide diffusing capacity; UCSD-SOBQ, The University of California in San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire.

Baseline lung function and exercise capacity were similar between the two groups. However, those receiving statins had a significantly higher prevalence of CV disease at baseline. The prevalence of the following CV risk factors was higher among statin users than non-users: hypertension, smoking (current and former), diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia (table 1).

Disease-related outcomes

Results from the crude analysis and bivariate frailty model are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Unadjusted 1-year risks of study outcomes for baseline statin users and non-users*†

| Outcome | Crude analysis, n (%) | Bivariate frailty model (statin users vs non-users) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statin users (N=276) | Statin non-users (N=348) | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Disease-progression composite outcome‡ | 103 (37.3) | 152 (43.7) | 0.0737 | 0.79 | 0.61 to 1.02 | 0.0686 |

| First disease-progression outcome to occur§ | ||||||

| All-cause mortality | 13 (4.7) | 19 (5.5) | ||||

| Absolute FVC decrease ≥10% | 32 (11.6) | 52 (14.9) | ||||

| 6MWD decrease ≥50 m | 62 (22.5) | 92 (26.4) | ||||

| Mortality | ||||||

| All-cause | 18 (6.5) | 24 (6.9) | 0.8528 | 0.91 | 0.49 to 1.68 | 0.7557 |

| IPF-related | 15 (5.4) | 23 (6.6) | 0.5423 | 0.71 | 0.33 to 1.54 | 0.3814 |

| FVC change | ||||||

| Absolute decrease ≥10% | 43 (15.6) | 70 (20.1) | 0.1440 | 0.67 | 0.46 to 0.99 | 0.0417 |

| Relative decrease ≥10% | 77 (27.9) | 108 (31.0) | 0.3943 | 0.77 | 0.57 to 1.03 | 0.0814 |

| Absolute decrease ≥5% | 109 (39.5) | 147 (42.2) | 0.4881 | 0.81 | 0.63 to 1.04 | 0.0958 |

| Relative decrease ≥5% | 134 (48.6) | 191 (54.9) | 0.1157 | 0.76 | 0.61 to 0.95 | 0.0174 |

| Death or absolute FVC decrease ≥10% | 57 (9.1) | 90 (14.4) | 0.1277 | 0.71 | 0.51 to 0.99 | 0.0437 |

| Death or 6MWD decrease ≥50 m | 99 (15.9) | 142 (22.8) | 0.2086 | 0.85 | 0.66 to 1.10 | 0.2157 |

| 6MWD decrease ≥50 m | 69 (25.0) | 97 (27.9) | 0.4918 | 0.85 | 0.62 to 1.16 | 0.3046 |

| Hospitalisation | ||||||

| All-cause | 47 (17.0) | 72 (20.7) | 0.2477 | 0.78 | 0.54 to 1.13 | 0.1818 |

| Respiratory-related¶ | 30 (10.9) | 59 (17.0) | 0.0309 | 0.64 | 0.41 to 1.00 | 0.0496 |

*Only confirmed cases included, defined as those for whom follow-up assessment was repeated ≥6 weeks following initial assessment and criteria for outcome were met.

†Patients with missing baseline data were excluded from relevant analyses.

‡Only first event considered in analyses.

§Number of patients who experienced each outcome as their first disease-progression event.

¶Hospitalisation in which the primary reason for admission was determined to be respiratory-related by a blinded clinical investigator.

6MWD, 6-minute walk distance; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

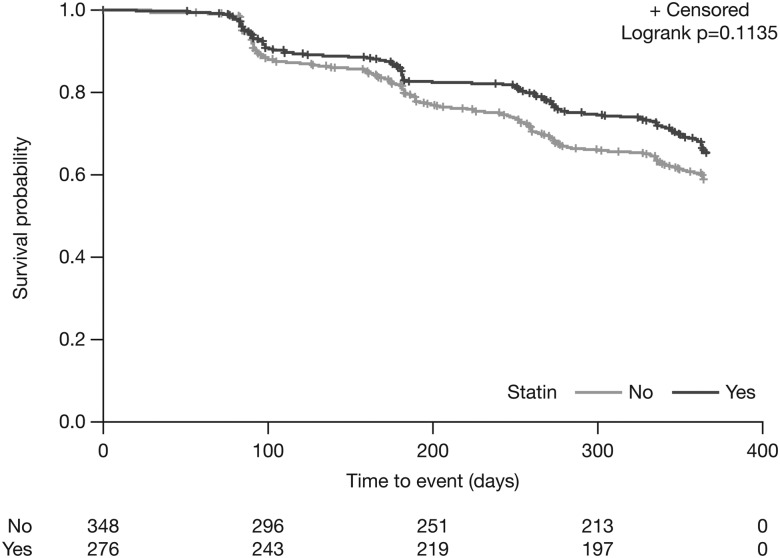

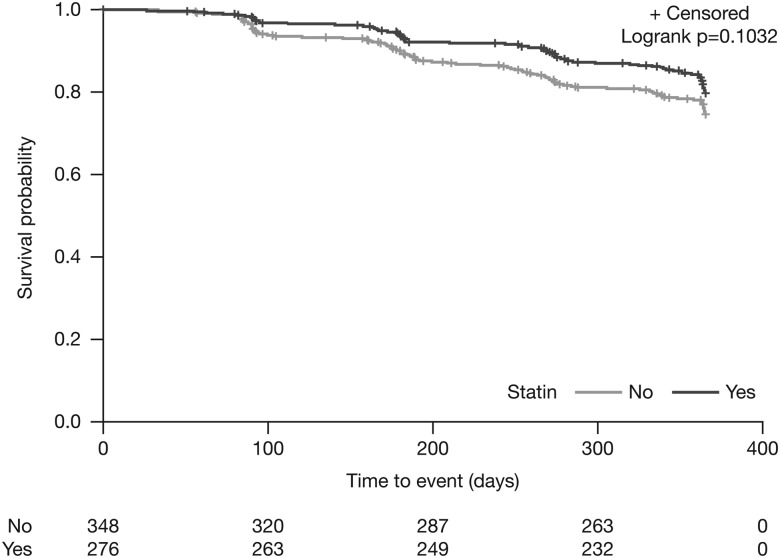

In multivariate analyses, there was a non-significant treatment effect favouring statin use for the composite disease-progression outcome (multivariate HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.52 to 1.07, p=0.1135) (figure 1; table 3). Statin users had a significantly lower risk versus non-users for the composite outcome of all-cause mortality or a decrease of ≥50 m in 6MWD (multivariate HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.48 to 0.99, p=0.0465), all-cause hospitalisation (multivariate HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.35 to 0.94, p=0.0289), respiratory-related hospitalisation (multivariate HR 0.44; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.80, p=0.0063) and IPF-related mortality (multivariate HR 0.36; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.95, p=0.0393) (table 3). There was no significant difference between treatment groups for ≥10% absolute decline in per cent predicted FVC (multivariate HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.47 to 1.40, p=0.4533), the composite outcome of all-cause mortality or a ≥10% decline in per cent predicted FVC (multivariate HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.07, p=0.1032) (figure 2) and all-cause mortality (multivariate HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.21, p=0.1369) (table 3).

Figure 1.

Adjusted 1-year risk of disease progression*: statin users versus non-users. *≥10% decrease in % predicted FVC, ≥50 m decline in 6MWD or death. 6MWD, 6-minute walk distance.

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses: baseline statin users versus non-users*

| Outcome | Multivariate analyses (statin users vs non-users) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Disease progression† | 0.75 | 0.52 to 1.07 | 0.1135 |

| Mortality | |||

| All-cause | 0.54 | 0.24 to 1.21 | 0.1369 |

| IPF-related | 0.36 | 0.14 to 0.95 | 0.0393 |

| FVC | |||

| Absolute decrease ≥10% | 0.81 | 0.47 to 1.40 | 0.4533 |

| Relative decrease ≥10% | 0.90 | 0.59 to 1.38 | 0.6262 |

| Absolute decrease ≥5% | 0.97 | 0.68 to 1.40 | 0.8805 |

| Relative decrease ≥5% | 0.91 | 0.66 to 1.25 | 0.5548 |

| Death or absolute FVC decrease ≥10% | 0.71 | 0.48 to 1.07 | 0.1032 |

| Death or 6MWD decrease ≥50 m | 0.69 | 0.48 to 0.99 | 0.0465 |

| Hospitalisation | |||

| All-cause | 0.58 | 0.35 to 0.94 | 0.0289 |

| Respiratory-related‡ | 0.44 | 0.25 to 0.80 | 0.0063 |

*Patients with missing baseline data were excluded from relevant analyses.

†Defined as ≥10% decrease in per cent predicted FVC, ≥50 m decline in 6MWD or death.

‡Hospitalisation in which the primary reason for admission was determined to be respiratory-related by a blinded clinical investigator.

6MWD, 6-minute walk distance; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Figure 2.

Adjusted 1-year risk of ≥10% absolute FVC decline or death: statin users versus non-users.

Discussion

The results of this post hoc analysis of data from patients with IPF from the placebo arms of the CAPACITY and ASCEND trials provide support for the hypothesis that statin therapy may have a beneficial effect on IPF-related outcomes. In particular, statins were associated with reduced hospitalisation and mortality.

Previous studies undertaken to evaluate the potential impact of statins on outcomes in patients with IPF have provided conflicting results. A small, retrospective analysis of data from 35 patients with IPF did not show an association between statin therapy and mortality.21 However, more than half of the patients in this study received immunosuppressive therapy which has recently been associated with increased mortality in the PANTHER trial25 and which may, therefore, have confounded the results. In contrast, a more recent analysis of data from the national Danish Patients Registry found that statin use was associated with reduced mortality among 783 patients with IPF. However, the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision coding was used in this analysis, and may have introduced bias due to poor definition of baseline lung function and other potential risk factors for adverse outcomes.22

Our analyses did not identify a beneficial interaction between statin use and current/former smoking status for any outcome contrary to previous observations reported by Alexeeff et al. Alexeeff et al15 reported a statistically significant (p<0.001) three-way interaction between time since first study visit, statin use and smoking status in elderly men enrolled in a longitudinal observational study. Their results suggested that statins might act by attenuating the negative effects of smoking on the normative decline in lung function associated with ageing. However, lung function decline in patients with IPF differs to that associated with normal ageing,8 26 27 thus complicating valid comparison between the two populations.

The pathophysiology of IPF is very complex and the mechanism by which statins may affect cellular and/or molecular pathways to reduce disease progression remains to be explained. Repetitive microscopic injury to alveolar epithelial cells type II (AECII) is thought to be an important component of the pathogenesis of IPF. AECII death and perturbation of normal epithelial homoeostasis may result in uncontrolled repair mechanisms, resulting in fibroblast proliferation and activation and, ultimately, lung fibrosis.28 29 Multiple pathways are involved both in AECII death and in lung fibrosis, and the relative contribution of these pathways in the development of IPF is currently an important knowledge gap. In vitro studies have long suggested a modulatory effect of statins on pathways of fibrosis in humans.30 31 In experiments using a human renal fibroblast cell line (TK173), exposure to statins resulted in a reversible and time-dependent change in cell morphology, including the actin skeleton, with concomitant changes in the basal expression of the profibrotic protein connective tissue growth factor.30 This finding was reproduced in an in vitro study that found a reduction in the expression of the profibrotic connective tissue growth factor in lung fibroblasts treated with statins.32 Perhaps more indirectly, statins have been shown to reduce the expression of the glycoprotein thrombospondin-1 by human vascular smooth muscle cells;31 thrombospondin-1 is a known activator of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), a key profibrotic protein implicated in fibrogenesis.33

Pathophysiological processes other than those related directly to fibrosis may also underpin a beneficial effect of statins in patients with IPF. Statins are known to exert an anti-inflammatory effect and it is possible that this action may explain the apparent protective effect of these agents in patients with IPF. In a rat model, statins appeared to be protective against smoking-induced lung damage through anti-inflammatory effects in the lung itself, particularly inhibition of inflammatory cell infiltration.34 Consistent with this latter observation, statin use was associated with reduced levels of neutrophils and lymphocytes in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients after lung transplantation with a variety of underlying diagnoses including emphysema, cystic fibrosis and IPF. The 6-year survival of patients with lung transplant who received statins was also significantly greater than that of patients who did not receive statins (91% vs 54%; p<0.01).35 Furthermore, statins have been shown to suppress the production of TGF-β and the inflammatory chemokine, interleukin (IL) 8, in human lung tissue.36–38 However, this is in contrast to an in vitro study which found that statins increased mitogen-activated peripheral blood monocyte secretion of IL-18 and IL-1β,39 two cytokines that have been implicated in bleomycin-induced lung injury.40

Our analysis was the first evaluation of statin use in a large, well defined cohort of patients with IPF with regular follow-up. In contrast to earlier evidence which had suggested a link between statin use and the development of interstitial lung abnormalities17 18 our results add weight to the hypothesis that statins may exert a beneficial effect in patients with IPF. However, the conclusions that can be drawn are limited by the post hoc nature of the analysis. Statin therapy may address an increased risk of all-cause death or hospitalisation as a result of comorbid conditions. Yet a comparison of the baseline characteristics of the patients in the two groups suggested that those receiving statins had higher CV risk than those not receiving statins, as might be expected given the CV-related indications for statin therapy. Additionally, our analyses have suggested a potentially more specific effect of statins on IPF-related mortality and respiratory-related hospitalisations, which might not be anticipated if the impact of statins was related only to CV comorbidities.

Furthermore, our results are limited to patients with IPF who are not treated with antifibrotics. Future studies of statins in IPF are likely to include patients receiving antifibrotics, therefore a post hoc analysis designed to investigate the effect of pirfenidone and statins in combination is planned, using data from the pirfenidone arms of the ASCEND and CAPACITY studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results presented here provide support for the hypothesis that statins may be beneficial in patients with IPF. Future studies should include prospective analyses of statin use in IPF and their potential use in combination with antifibrotic therapies.

Footnotes

Contributors: MKr, MKo and DW were involved in the design of the analysis. DW was involved in the execution of the analysis. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the results. All authors were involved in drafting and revising this manuscript, and provided final approval of the version to be published. All authors vouch for the accuracy of the content included in the final manuscript.

Funding: The sponsor, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, funded the analysis of the data by Policy Analysis Inc. (PAI). Programming support was provided by Mark Atwood of Policy Analysis Inc. (PAI). Medical writing support was provided by Dr Tracey Lonergan on behalf of Complete Medical Communications Ltd, funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Competing interests: MKr and his institution have received unrestricted grants and personal fees from InterMune International AG which became a wholly owned subsidiary of Roche in 2014, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and Boehringer Ingelheim. FB has received speaker fees, advisory board honoraria or grants from InterMune International AG which became a wholly owned subsidiary of Roche in 2014, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Serendex, Centocor and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. TMM is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Clinician Scientist Fellowship (NIHR Ref: CS:-2013-13-017). He has received research grants from GlaxoSmithKline, UCB and Novartis; and consulting and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biogen Idec, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cipla, Dosa, GlaxoSmithKline, Lanthio, InterMune International AG which became a wholly owned subsidiary of Roche in 2014, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda and UCB. UC has received grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim. He has received grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Intermune International AG which became a wholly owned subsidiary of Roche in 2014, and personal fees from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Bayer, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, UCB, Biogen and Centocor (all outside the submitted work). PS has received consulting fees from InterMune International AG which became a wholly owned subsidiary of Roche in 2014, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and Santhera Pharmaceuticals Ltd, and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis. DW is an employee of Policy Analysis Inc. (PAI), which received funding from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd for this study. K-UK is an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland. MKo has served as site Principal Investigator in industry-sponsored clinical trials (Centocor, Roche, Sanofi and Boehringer Ingelheim) and is funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research. He has served and/or serves on the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Medical Advisory Board and on Advisory Boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Vertex, Genoa, Gilead, Janssen and Prometic.

Ethics approval: Ethics committee/institutional review board approval was obtained from each centre participating in the ASCEND and CAPACITY studies (total of 237 centres) as presented in the primary papers reporting the results of those trials (King et al,9 and Noble et al,10). A full list can be provided if required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Meltzer EB, Noble PW. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008;3:8 10.1186/1750-1172-3-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:788–824. 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:e3–19. 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behr J, Kreuter M, Hoeper MM, et al. Management of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in clinical practice: the INSIGHTS-IPF registry. Eur Respir J 2015;46:186–96. 10.1183/09031936.00217614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durheim MT, Collard HR, Roberts RS, et al. Association of hospital admission and forced vital capacity endpoints with survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of a pooled cohort from three clinical trials. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3:388–96. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00093-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2016. American Cancer Society, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nathan SD, Shlobin OA, Weir N, et al. Long-term course and prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the new millennium. Chest 2011;140:221–9. 10.1378/chest.10-2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim DS, Collard HR, King TE Jr. Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:285–92. 10.1513/pats.200601-005TK [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2083–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet 2011;377:1760–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60405-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2071–82. 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreuter M, Ehlers-Tenenbaum S, Palmowski K, et al. Impact of comorbidities on mortality in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0151425 10.1371/journal.pone.0151425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bansilal S, Castellano JM, Fuster V. Global burden of CVD: focus on secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol 2015;201(Suppl 1):S1–7. 10.1016/S0167-5273(15)31026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briel M, Vale N, Schwartz GG, et al. Updated evidence on early statin therapy for acute coronary syndromes: meta-analysis of 18 randomized trials involving over 14,000 patients. Int J Cardiol 2012;158:93–100. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexeeff SE, Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, et al. Statin use reduces decline in lung function: VA Normative Aging Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:742–7. 10.1164/rccm.200705-656OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Criner GJ, Connett JE, Aaron SD, et al. Simvastatin for the prevention of exacerbations in moderate-to-severe COPD. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2201–10. 10.1056/NEJMoa1403086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández AB, Karas RH, Alsheikh-Ali AA, et al. Statins and interstitial lung disease: a systematic review of the literature and of food and drug administration adverse event reports. Chest 2008;134:824–30. 10.1378/chest.08-0943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu JF, Washko GR, Nakahira K, et al. Statins and pulmonary fibrosis: the potential role of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:547–56. 10.1164/rccm.201108-1574OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saad N, Camus P, Suissa S, et al. Statins and the risk of interstitial lung disease: a cohort study. Thorax 2013;68:361–4. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroll S, Lange TJ, Arzt M, et al. Effects of simvastatin on pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension and exercise capacity in bleomycin-treated rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2013;208:191–201. 10.1111/apha.12085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadrous HF, Ryu JH, Douglas WW, et al. Impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and statins on survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2004;126:438–46. 10.1378/chest.126.2.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Statin use is associated with reduced mortality in patients with interstitial lung disease. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0140571 10.1371/journal.pone.0140571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide. 2nd edn. North Carolina: SAS Insitute Inc, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, D'Agostino RB Jr, et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157–72. 10.1002/sim.2929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE Jr, et al. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1968–77. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ley B, Collard HR, King TE Jr. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:431–40. 10.1164/rccm.201006-0894CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1324–43. 10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chambers RC, Mercer PF. Mechanisms of alveolar epithelial injury, repair, and fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12(Suppl 1):S16–20. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-448MG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Günther A, Korfei M, Mahavadi P, et al. Unravelling the progressive pathophysiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 2012;21: 152–60. 10.1183/09059180.00001012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eberlein M, Heusinger-Ribeiro J, Goppelt-Struebe M. Rho-dependent inhibition of the induction of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins). Br J Pharmacol 2001;133:1172–80. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riessen R, Axel DI, Fenchel M, et al. Effect of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on extracellular matrix expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Basic Res Cardiol 1999;94:322–32. 10.1007/s003950050158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watts KL, Sampson EM, Schultz GS, et al. Simvastatin inhibits growth factor expression and modulates profibrogenic markers in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;32:290–300. 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0127OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J 2004;18:816–27. 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, Lee DS, Kim EK, et al. Simvastatin inhibits cigarette smoking-induced emphysema and pulmonary hypertension in rat lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:987–93. 10.1164/rccm.200501-041OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson BA, Iacono AT, Zeevi A, et al. Statin use is associated with improved function and survival of lung allografts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1271–8. 10.1164/rccm.200205-410OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn MH, Park BL, Lee SH, et al. A promoter SNP rs4073T>A in the common allele of the interleukin 8 gene is associated with the development of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis via the IL-8 protein enhancing mode. Respir Res 2011;12:73 10.1186/1465-9921-12-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayden JM, Swartfiguer J, Szelinger S, et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulation of alveolar epithelial cell interleukin-8 production and neutrophil chemotaxis is inhibited by statin treatment [abstract]. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2005;2:A72. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oka H, Ishii H, Iwata A, et al. Inhibitory effects of pitavastatin on fibrogenic mediator production by human lung fibroblasts. Life Sci 2013;93:968–74. 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coward WR, Marei A, Yang A, et al. Statin-induced proinflammatory response in mitogen-activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells through the activation of caspase-1 and IL-18 secretion in monocytes. J Immunol 2006;176:5284–92. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoshino T, Okamoto M, Sakazaki Y, et al. Role of proinflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-1beta in bleomycin-induced lung injury in humans and mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;41:661–70. 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0182OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]