Abstract

Background

The clinical implications of the diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) are very different. Yet there are “borderline” breast lesions that have characteristics of both ADH and DCIS. We examined interobserver diagnostic variability for such lesions and correlated pathologic features of the lesions with clinical outcomes.

Methods

We identified all cases of borderline ADH/DCIS lesions treated at our center from 1997 to 2010. Five specialized breast pathologists blinded to clinical outcomes independently reviewed all available slides from each case and were instructed to classify each as benign, ADH, or DCIS. A majority diagnosis (MajDx) was defined as a diagnosis agreed upon by ≥3 pathologists.

Results

A total of 105 women with borderline ADH/DCIS and slides available for review were identified. The MajDx was ADH in 84 (80%), and DCIS in 18 (17%). There were split diagnoses in 3 (3%). MajDx of DCIS correlated significantly with lesion size and nuclear grade. There was diagnostic agreement by all 5 pathologists in 30% of cases, 4 pathologists in 42%, and 3 pathologists in 25%. At a median follow-up of 37 months, 4 (3.8%) patients developed subsequent ipsilateral breast carcinoma (2 invasive, 2 DCIS); all 4 cases had MajDx of ADH.

Conclusions

Borderline ADH/DCIS represents an entity for which reproducible categorization as ADH or DCIS cannot be achieved. Furthermore, histologic features of borderline lesions resulting in MajDx of ADH vs. DCIS are not prognostic for risk of subsequent breast carcinoma.

Keywords: atypical ductal hyperplasia, ductal carcinoma in situ, borderline, interobserver agreement, outcome

Introduction

Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) is an intraductal proliferation of monomorphic epithelial cells with histologic and cytologic features resembling those seen in low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).1 However, the atypical proliferation in ADH is either admixed with a second population of proliferative cells without atypia, or completely involves the terminal ductal lobular unit(s) to a limited extent. The distinction between ADH and low-grade DCIS has important clinical implications, as the management of these lesions differs greatly. However, no single qualitative feature reproducibly distinguishes ADH from low-grade DCIS, as both are part of the same morphologic spectrum and closely related at the molecular level. Lesion size provides a quantitative criterion to distinguish ADH from low-grade DCIS, and involvement of 2 separate ducts or size >2 mm have been proposed as arbitrary cutoff points.2,3

Rarely, pathologists encounter “borderline” intraductal proliferations that are difficult to classify as either ADH or DCIS. In some cases, the cytologic atypia is similar to that of low-grade DCIS, but the lesion spans ≤2 mm. Other lesions are composed of cells with low-grade cytologic atypia spanning >2 mm, but only partially involve ducts and/or lobules, or consist of minute skip lesions in a background of columnar cell changes with atypia/flat epithelial atypia. These borderline proliferations often engender different diagnostic opinions among pathologists. At our institution, these lesions are usually termed “markedly ADH bordering on DCIS” (borderline ADH/DCIS).

Here, we assessed interobserver variability among 5 specialized breast pathologists using standard criteria to categorize such borderline ADH/DCIS lesions into 1 of 3 categories: benign, ADH, or DCIS. We also sought to compare the histopathologic features of lesions for which the majority of pathologists diagnosed DCIS versus those for which most pathologists diagnosed ADH, and examine the long-term outcomes of these 2 groups.

Materials and Methods

After institutional review board approval, we searched institutional pathology records and databases for all women with a borderline ADH/DCIS diagnosis in either the core biopsy or excision specimen from 1997 to 2010. Borderline lesions were defined as those with the pathologic diagnosis of “markedly ADH bordering on low-grade DCIS” or “markedly ADH focally reaching the level of DCIS.” We excluded any cases of “atypical ductal hyper-plasia” not further qualified, and cases in which diagnosis of borderline lesion in a core biopsy was upgraded to DCIS or invasive carcinoma on surgical excision specimen examination. We recorded patient age, family history (at least one first- or second-degree relative with breast cancer), menopausal status, and any radiation therapy, endocrine therapy, or chemotherapy. We collected clinical outcome data, including time interval to ipsilateral breast carcinoma (DCIS or invasive breast carcinoma), tumor type, and location (same quadrant or different quadrant) of any subsequent ipsilateral carcinoma.

All available diagnostic slides were reviewed independently by 5 study pathologists blinded to the clinical outcome. All 5 specialize in breast pathology in the same group, meet for consensus conferences twice a week, and adhere to the same diagnostic guidelines in their daily practice. Each was instructed to independently score each case as 1 = benign, 2 = ADH, or 3 = DCIS according to criteria summarized by Page and Rogers.1 Diagnosis of borderline lesion was not an option. Consultation between study pathologists was not allowed.

The reviewers assessed lesion size (≤2 mm, or >2 mm), nuclear grade (low = 1, intermediate = 2, high = 3), histologic pattern of the index lesion as well as presence of associated calcifications. Cases with even only focal intermediate-grade nuclei in the background of low nuclear grade were classified as nuclear grade “1 to 2.” For study purposes, each duct or terminal duct-lobular unit involved by the atypical proliferation was classified as one “duct,”4 and the number of involved ducts (1, 2, or >2) was recorded. We also noted presence of atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) or classical lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) in each case. At our institution, different surgical excision specimen margin assessment methods have been used. Between July 2004 and July 2007, a 2- to 3-mm thick rim of tissue was shaved by the pathologist from the entire surface of the inked excision specimen. The shaved tissue was then submitted entirely en face. Presence of the lesion in a shaved margin section was interpreted as “positive” margin. Before July 2004 and after July 2007, we evaluated perpendicular sections to all surgical margins and recorded lesion distance to the closest margin.

All diagnoses rendered by the 5 pathologists were recorded. The majority diagnosis (MajDx) for each case reflects agreement by ≥3 pathologists.

Pathologic/clinical variables associated with MajDx of ADH versus DCIS were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Case scoring differences between pathologists were assessed using ANOVA. We also correlated the MajDx, clinical and pathological variables with subsequent ipsilateral breast carcinoma occurrence.

Results

A total of 142 women received pathological diagnosis of “markedly ADH bordering on DCIS” or “markedly ADH focally reaching the level of DCIS” (borderline ADH/ DCIS) during the study period (1997–2010), for which 105 had all slides from biopsy and excision specimens available for review. These 105 constitute a patient subset from an aforepublished series.5

All 105 patients underwent surgical excisions, including 34 excisional biopsies and 71 surgical excisions after core needle biopsy. In 37 (35%) patients, ADH/DCIS was diagnosed only in core biopsy but was not present in the subsequent surgical excision specimen. In 6 (6%) patients, ADH/DCIS was present in both core biopsy and the subsequent surgical excision specimens. In the remaining 62 (59%) patients, ADH/DCIS was diagnosed in excision specimens only, including 34 excisional biopsies, 27 surgical excisions for high-risk lesions found in core biopsies (ADH = 15, LCIS = 4, ALH = 2, columnar cell changes with atypia = 1, intraductal papilloma = 4, fibroepithelial lesion = 1), and 1 surgical excision for discordant radiologic pathologic findings.

Table 1 shows patient characteristics. Surgical margin status was assessed with perpendicular sections in 97 cases, and with shaved margin sections in 8. Negative final margins (defined as index lesion >1 mm away from the inked margin in the perpendicular sections or not present in the shaved margin sections) was achieved in 98 of 105 cases (93%). The index lesion was within 1 mm of the perpendicular inked margin in 5 patients and in the shaved margin sections in 2.

Table 1.

Summary of the 105 Patients.

| Entire Population (n = 105), a n (%) | MajDx of ADH (n = 84), n (%) | MajDx of DCIS (n = 18), n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 51 (19–85) | 51 (19–85) | 51 (41–72) | .6 |

| Premenopausal | 53/105 (50) | 44/84 (52) | 9/18 (50) | 1.0 |

| Family history breast cancer | 41/105 (39) | 31/84 (37) | 7/18 (39) | 1.0 |

| Reason for biopsy | ||||

| Calcifications | 74/105 (70) | 58/84 (69) | 14/18 (78) | .6 |

| Mass | 26/105 (25) | 22/84 (26) | 4/18 (22) | 1.0 |

| MRI abnormality | 5/105 (5) | 4/84 (5) | 0/18 (0) | 1.0 |

| Diagnosis of ADH/DCIS | ||||

| Core biopsy only | 37/105 (35) | 32/84 (38) | 5/18 (28) | .6 |

| Excision only | 62/105 (59) | 47/84 (57) | 12/18 (67) | .4 |

| Both | 6/105 (6) | 5/84 (6) | 1/18 (6) | 1.0 |

| Surgical margin | ||||

| Negative | 98/105 (93) | 77/84 (92) | 18/18 (100) | .3 |

| Close or positive | 7/105 (7)b | 7/84 (8) | 0/18 (0) | .3 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Endocrine therapy | 14/105 (13) | 11/84 (13) | 3/18 (17) | .7 |

| Otherc | 1/105 (1) | 1/84 (1) | 0/18 (0) | 1.0 |

Abbreviation: ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; MajDx, majority diagnosis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Three cases had split diagnoses (no MajDx).

Five patients with lesion ≤1 mm to the margin (perpendicular margin); 2 patients with lesion in the shaved margin.

One patient received chemotherapy and radiation for contralateral invasive ductal carcinoma.

Table 2 shows entire population pathologic features and those with MajDx of ADH and DCIS. No index lesions had high nuclear grade or necrosis.

Table 2.

Pathologic Features of Cases in Entire Population and Comparison Between Cases With MajDx of ADH and DCIS.

| Entire population (n = 105), a n (%) | MajDx ADH (n = 84), n (%) | MajDx DCIS (n = 18), n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size, mm, mean (95% CI) | 2.48 (2.13–2.83) | 2.30 (1.94–2.66) | 3.26 (2.12–4.40) | .04 |

| Size, mm | .03 | |||

| ≤2 | 67 (64) | 58 (69) | 7 (39) | |

| >2 | 38 (36) | 26 (31) | 11 (61) | |

| No. of involved ducts | .12 | |||

| 1 | 15 (14) | 14 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 8 (8) | 7 (8) | 1 (6) | |

| >2 | 82 (78) | 63 (75) | 17 (94) | |

| Nuclear grade | .03 | |||

| 1 | 89 (85) | 74 (88) | 12 (67) | |

| 1–2 | 16 (15) | 10 (12) | 6 (33) | |

| Calcifications in lesion | 61 (58) | 51 (61) | 9 (50) | .44 |

| Classic LCIS or ALH | 35 (33) | 25 (30) | 10 (56) | .05 |

Abbreviations: ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; ALH, atypical lobular hyperplasia; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ; MajDx, majority diagnosis; nuclear grade 1–2, low grade with focal intermediate nuclear grade.

Three cases had split diagnoses (no MajDx).

Majority Diagnosis and Individual Diagnosis

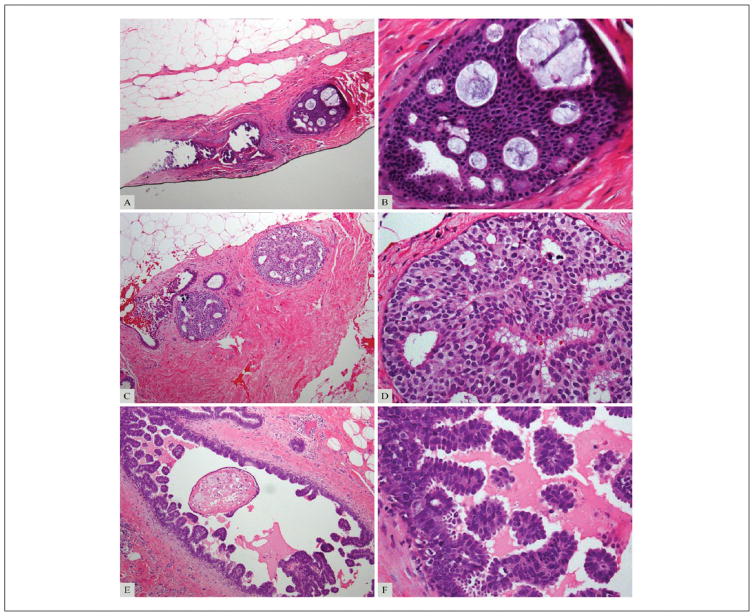

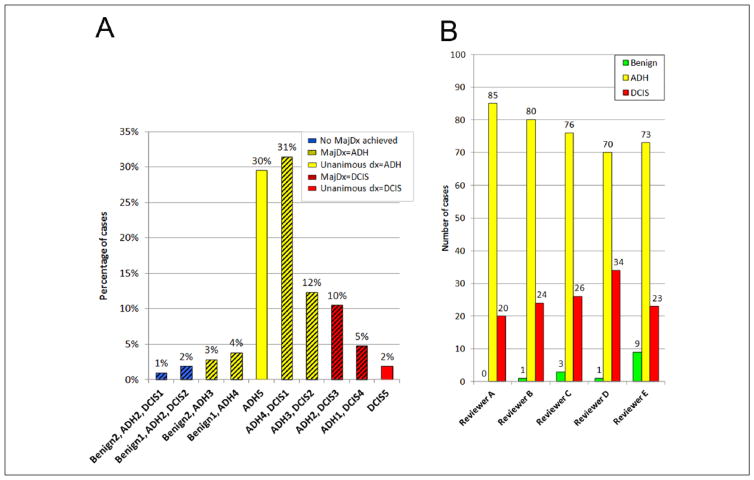

On re-review, with the pathologists forced to categorize each lesion as benign, ADH, or DCIS, the most frequent MajDx was ADH (84/105; 80%), followed by DCIS (18/105; 17%). Three (3%) cases had no MajDx (diagnoses split among benign, ADH, and DCIS). No case had a benign MajDx. There was diagnostic agreement by all 5 reviewers in 32/105 cases (30%); 30 were unanimously scored as ADH (Figure 1A and B, Figure 2A), and 2 were scored as DCIS (Figure 1C and D, Figure 2A). There was diagnostic agreement by 4 reviewers in 44/105 cases (42%), including 39 cases with MajDx of ADH and 5 with MajDx of DCIS. Diagnostic agreement by ≥4 reviewers was reached in 76/105 (72%) cases total (69 MajDx ADH, 7 MajDx DCIS). In 26/105 cases (25%) 3 reviewers agreed on the diagnosis (Figure 1E and F, Figure 2A).

Figure 1.

(A, B). Example of a case with consensus diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH; complete agreement by all 5 reviewers). (C, D). Example of a case with consensus diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS; complete agreement by all 5 reviewers). (E, F). Example of a case with majority diagnosis of DCIS (agreement by 3 of 5 reviewers). Magnification 100× (A, C, E) and 400× (B, D, F).

Figure 2.

Variability in diagnoses by case and by reviewer. (A) Proportion of cases by diagnosis category. Number of reviewers making each diagnosis is shown on the horizontal axis. Solid bars indicate complete agreement by all 5 pathologists. Hatched bars indicate lack of complete agreement. Red bars indicate cases in which the majority diagnosis was ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS); yellow bars indicate those in which the majority diagnosis was atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH); blue bars indicate those cases in which there was no majority diagnosis. (B) Number of cases categorized as benign, ADH, and DCIS, by reviewer.

ADH was the most frequent diagnosis rendered by individual pathologists (384/525;73%), followed by DCIS (127/525;24%). Fourteen (3%) individual diagnoses were benign. Average diagnostic score for 105 cases was 2.21 (95% CI = 2.16–2.27) (1 = benign, 2 = ADH, or 3 = DCIS). Average diagnostic scores for the 5 independent reviewers were as follows: A 2.19, B 2.23, C 2.21, D 2.31, and E 2.13, and were not significantly different (P = .085). No reviewer categorized consistently more lesions as ADH or DCIS than other reviewers (Figure 2B).

Pathologic Features

Table 2 summarizes the pathologic features of cases with MajDx of ADH and DCIS. Lesions with a DCIS MajDx were larger (mean size 3.26 mm vs 2.30 mm for MajDx ADH, P = .04) with 61% of cases being >2 mm versus 31% of those with MajDx ADH (P = .03). DCIS MajDx also correlated significantly with the presence of focal intermediate nuclear grade (33% of MajDx DCIS vs 12% MajDx ADH; P = .03). There is a trend of more frequent ALH and/or LCIS in the specimen with DCIS MajDx but did not reach statistical significance (56% of MajDx DCIS vs 30% of MajDx ADH; P = .05) (Table 2). Necrosis was absent in all cases. Clinical features, including patient age, menopausal status, family history of breast cancer, radiographic presentation, status of final surgical margin, and adjuvant endocrine therapy were similar in patients with ADH and DCIS MajDxs (Table 1). No patient received adjuvant radiation.

Clinical Outcome

Median follow-up time for all patients was 37 months (range <1 to 156 months), with median follow-up of 38 and 34 months for those with MajDx of ADH and DCIS, respectively (P = .2). Four (3.8%) patients developed ipsilateral breast carcinoma (2 DCIS, 2 invasive ductal carcinomas) at 1 to 10 years’ follow-up (Table 3). The carcinoma occurred in the same quadrant as the index lesion in 3 patients. In 3 of the 4 patients, index ADH/DCIS lesion was present in a core biopsy specimen targeting mammographic calcifications. The surgical excision specimen had LCIS, ADH, and biopsy site changes in 1 patient, and benign breast tissue with biopsy site changes and no atypia in the other 2. The fourth patient had a history of LCIS and ADH, and was undergoing routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening. Biopsy of an MRI abnormality yielded ADH. The index lesion of ADH/DCIS was diagnosed in the surgical excision specimen, with negative surgical margins (perpendicular margin assessment). None of the 4 patients received endocrine therapy during the time interval between ADH/DCIS index diagnosis and subsequent carcinoma. Two of the 4 patients had family history of breast cancer.

Table 3.

Summary of Patients With Subsequent Ipsilateral Breast Carcinoma (Invasive Carcinoma or DCIS).

| Characteristics | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | ||||

| Age (years) at diagnosis of ADH/DCIS | 48 | 42 | 52 | 83 |

| Menopausal status | Premenopausal | Premenopausal | Postmenopausal | Postmenopausal |

| Family history of breast cancer | Yes, second degree | No | No | Yes, first degree |

| Indication for biopsy | Calcifications | Calcifications | MRI abnormality | Calcifications |

| Adjuvant therapy | None | None | None | None |

| Pathological | ||||

| ADH/DCIS diagnosis | Core biopsy only | Core biopsy only | Excision | Core biopsy only |

| ADH/DCIS size, mm | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| No. of ducts involved | >2 | >2 | >2 | 2 |

| Predominant architecture | Flat | Micropapillary | Cribriform | Micropapillary |

| Nuclear grade | 1–2 | 1 | 1–2 | 1 |

| Classic LCIS or ALH | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Final margin status | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Consensus diagnosis | ADH | ADH | ADH | ADH |

| Interobserver agreement | 3 of 5 | 4 of 5 | 4 of 5 | 4 of 5 |

| Subsequent ipsilateral breast carcinoma | ||||

| Interval, years | 3 | 10 | 4 | 1 |

| Histology | DCIS | DCIS | Invasive ductal | Invasive ductal ca with focal mucin |

| Site in relation to ADH/DCIS | Same quadrant | Same quadrant | Same quadrant | Different quadrant |

| Histological grade | Not applicable | Not applicable | III | III |

| Nuclear grade | High | Intermediate | II | II |

| Size, cm | 0.8 | Not available | 1.2 | 2 |

| Receptor status | Not available | ER+ | ER+, PR−, HER2− | ER+, PR+, HER2− |

Abbreviations: ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; ALH, atypical lobular hyperplasia; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The 2 cases of invasive carcinoma developed 1 year and 4 years after index diagnosis. Both tumors were invasive ductal carcinoma, moderately differentiated, estrogen receptor positive, and HER2 negative. One invasive carcinoma arose in the same quadrant as the index borderline ADH/DCIS, the other was in a different quadrant. Two cases of DCIS were diagnosed 3 and 10 years after the index lesion and involved the same quadrant. DCIS had high nuclear grade in one patient and intermediate nuclear grade in the other.

Index lesions of all 4 patients had ADH MajDx on re-review, with diagnostic agreement by 4 of 5 pathologists in 3 cases, and agreement by 3 in the fourth case. All 4 lesions spanned ≤2 mm, although 3 involved more than 2 ducts. Two lesions had focal intermediate nuclear grade. Table 3 summarizes the clinicopathologic features of the 4 patients with subsequent development of ipsilateral carcinoma.

The remaining 101 patients had no clinical and radiological evidence of disease at follow-up or benign findings in additional ipsilateral breast biopsy specimens.

Discussion

Differential diagnosis of mammary borderline ductal epithelial proliferations has significant clinical implications for patient management. In most cases, established diagnostic criteria allow reliable distinction between ADH and DCIS. Lesion extent, such as >2 mm span and involvement of ≥2 separate basement membrane bound spaces (ie, ducts) are quantitative criteria proposed in the past for DCIS diagnosis.2,3 However, as noted by Masood and Rosa,6 “morphologic and quantitative measure are quite subjective and somewhat arbitrary.” Therefore, the differential diagnosis of ADH and low-grade DCIS is occasionally challenging.

Rosai7 found high interobserver variability in the diagnostic interpretation of 10 borderline ductal epithelial lesions among 5 experienced surgical pathologists. Among 6 expert breast pathologists (including 3 of the 5 from Rosai’s study) given standardized diagnostic criteria, Schnitt et al8 reported complete diagnostic agreement in only 58% of 24 proliferative ductal lesions. Among the 24 cases, there was complete agreement for 8 usual ductal hyperplasia cases, 4 ADH cases, and 2 DCIS cases.8 Of the 10 lesions with diagnostic disagreement, 8 revolved around differential diagnosis of ADH versus DCIS, documenting intrinsic difficulties in separating the two entities. The difficulties are unsurprising, as several studies have shown these lesions are part of a morphologic continuum with similar immunoprofile and genetic alterations.2,9–14

Elmore et al15 recently evaluated diagnostic concordance among pathologists interpreting breast biopsy specimens and reported a 75.3% overall diagnostic concordance rate among 115 participating pathologists compared with the reference diagnosis rendered by 3 expert breast pathologists. The lowest concordance rate among pathologists (48%) was for atypical cases.15 Notably, the diagnostic concordance rate for the 3 breast pathology experts with their consensus reference diagnosis was only 80% for atypical cases. These results underscore limitations in the application of available criteria to separate ADH and low-grade DCIS.

Current clinical practice does not account for “borderline” treatment strategies in patients with markedly ADH bordering on DCIS. DCIS is managed with surgical excision to clear margins alone or followed by radiation, consideration of endocrine therapy, and possibly mastectomy. In contrast, ADH diagnosis prompts clinical and radiological surveillance, and consideration of endocrine therapy for risk reduction.

Few studies have investigated the clinical significance of borderline ADH/low-grade DCIS lesions. Vandenbussche et al16 studied 74 cases with borderline ADH/DCIS diagnosis at core biopsy. Upgrade rate at excision was 49% (44% with DCIS, 4% with DCIS and invasive ductal carcinoma). Thirty-eight of 74 patients did not have a more severe diagnosis on excision and received no further treatment. One of the 38 patients developed low-grade DCIS 3 years after index diagnosis. Coopey et al17 reviewed pathology reports from 3 institutions and identified 161 patients with severe ADH bordering on DCIS treated with surgical excision. At 68 months’ mean follow-up, 6.8% (11/161) of patients with severe ADH bordering on DCIS developed ipsilateral (10/161) or bilateral (1/161) breast cancer. In the same study, ipsilateral (34/713) or bilateral (1/713) breast cancer developed in 4.9% (35/713) patients with ADH. This study did not include central pathology review of cases.

Choi et al5 reported clinical outcomes of 143 patients with borderline lesions who underwent surgical excision at our institution from 1997 to 2010. At 2.9 years’ median follow-up, 7 (4.9%) patients had developed ipsilateral breast carcinoma. The 5-year ipsilateral breast carcinoma rate was 7.7%, similar to that for patients with DCIS (7.2%) treated at the same center during the same time period. Pathology diagnoses were extracted from the original reports. While all patients in Choi et al5 had final surgical excision at our institution, some underwent core biopsy and/or excisional biopsy at other institutions, and slides with ADH/DCIS were no longer available for re-review for the current study, accounting for the differences in study populations.

To our knowledge, our study is the first correlating morphologic and quantitative features of borderline ductal proliferations and clinical outcomes in a large contemporary series. Our findings confirm interobserver variability when specialized breast pathologists are forced to categorize these challenging borderline lesions as ADH or DCIS. A majority diagnosis of DCIS was significantly associated with lesion size, size >2 mm and the presence of focal intermediate nuclear grade.

However, analysis of various histologic parameters did not identify any morphologic feature predictive of subsequent ipsilateral breast carcinoma development. All 4 women (3.8%) who had developed ipsilateral breast carcinoma (DCIS or invasive) at 4 years’ median follow-up had majority diagnosis of ADH on re-review by 5 specialized breast pathologists forced to choose between ADH and DCIS.

This study has several limitations. First, at our center, we report margin status for ADH/DCIS in the excision specimens. Many patients in our series underwent re-excision for positive or close margins. This practice may not reflect that at other institutions. Second, the median follow-up time of 37 months was relatively short. We will continue to follow our patient cohort and obtain outcome data with long-term follow-up.

In conclusion, ADH and low-grade DCIS are part of a spectrum of lesions with overlapping cytologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular features, and borderline lesions exist that defy categorization as either ADH or DCIS, even using immunohistochemical markers or molecular analysis.10–14 In these cases, interobserver interpretation differences do not constitute a “shortcoming” of traditional morphologic diagnosis, but rather an indication of the lesions’ borderline nature. Using current diagnostic criteria, categorization of challenging borderline ductal lesions remains variable. No histologic feature can predict the risk of breast carcinoma among these patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by a Cancer Center Support Grant of the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (Grant No. P30CA008748).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Page DL, Rogers LW. Combined histologic and cytologic criteria for the diagnosis of mammary atypical ductal hyperplasia. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:1095–1097. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Rados MS. Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast. A long-term follow-up study. Cancer. 1985;55:2698–2708. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850601)55:11<2698::aid-cncr2820551127>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. A comparison of the results of long-term follow-up for atypical intraductal hyperplasia and intraductal hyperplasia of the breast. Cancer. 1990;65:518–529. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900201)65:3<518::aid-cncr2820650324>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ely KA, Carter BA, Jensen RA, Simpson JF, Page DL. Core biopsy of the breast with atypical ductal hyperplasia: a probabilistic approach to reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1017–1021. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi DX, Eaton AA, Olcese C, Patil S, Morrow M, Van Zee KJ. Blurry boundaries: do epithelial borderline lesions of the breast and ductal carcinoma in situ have similar rates of subsequent invasive cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1302–1310. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2719-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masood S, Rosa M. Borderline breast lesions: diagnostic challenges and clinical implications. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:190–198. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31821698cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosai J. Borderline epithelial lesions of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:209–221. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnitt SJ, Connolly JL, Tavassoli FA, et al. Interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of ductal proliferative breast lesions using standardized criteria. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1133–1143. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page DL. Cancer risk assessment in benign breast biopsies. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:871–874. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(86)80636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moinfar F, Man YG, Lininger RA, Bodian C, Tavassoli FA. Use of keratin 35βE12 as an adjunct in the diagnosis of mammary intraepithelial neoplasia-ductal type—benign and malignant intraductal proliferations. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1048–1058. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otterbach F, Bankfalvi A, Bergner S, Decker T, Krech R, Boecker W. Cytokeratin 5/6 immunohistochemistry assists the differential diagnosis of atypical proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2000;37:232–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grin A, O’Malley FP, Mulligan AM. Cytokeratin 5 and estrogen receptor immunohistochemistry as a useful adjunct in identifying atypical papillary lesions on breast needle core biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1615–1623. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181aec446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boecker W, Buerger H, Schmitz K, et al. Ductal epithelial proliferations of the breast: a biological continuum? Comparative genomic hybridization and high-molecular-weight cytokeratin expression patterns. J Pathol. 2001;195:415–421. doi: 10.1002/path.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdel-Fatah TM, Powe DG, Hodi Z, Reis-Filho JS, Lee AH, Ellis IO. Morphologic and molecular evolutionary pathways of low nuclear grade invasive breast cancers and their putative precursor lesions: further evidence to support the concept of low nuclear grade breast neoplasia family. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:513–523. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318161d1a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elmore JG, Longton GM, Carney PA, et al. Diagnostic concordance among pathologists interpreting breast biopsy specimens. JAMA. 2015;313:1122–1132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandenbussche CJ, Khouri N, Sbaity E, et al. Borderline atypical ductal hyperplasia/low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ on breast needle core biopsy should be managed conservatively. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:913–923. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828ba25c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coopey SB, Mazzola E, Buckley JM, et al. The role of chemoprevention in modifying the risk of breast cancer in women with atypical breast lesions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136:627–633. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]