Abstract

Key points

Intracellular pH regulation is vital to neurons as nerve activity produces large and rapid acid loads in presynaptic terminals.

Rapid clearance of acid loads is necessary to maintain control of neurotransmission, but neuronal acid clearance mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Glutamate is loaded into synaptic vesicles via the vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT), a mechanism conserved across phyla, and this study reports a previously unknown role for VGLUT as an acid‐extruding protein when deposited in the plasmamembrane during exocytosis.

The finding was made in Drosophila (fruit fly) larval motor neurons through a combined pharamacological and genetic dissection of presynaptic pH homeostatic mechanisms.

A dual role for VGLUT serves to integrate neuronal activity and pH regulation in presynaptic nerve terminals.

Abstract

Neuronal activity can result in transient acidification of presynaptic terminals, and such shifts in cytosolic pH (pHcyto) probably influence mechanisms underlying forms of synaptic plasticity with a presynaptic locus. As neuronal activity drives acid loading in presynaptic terminals, we hypothesized that the same activity might drive acid efflux mechanisms to maintain pHcyto homeostasis. To better understand the integration of neuronal activity and pHcyto regulation we investigated the acid extrusion mechanisms at Drosophila glutamatergic motorneuron terminals. Expression of a fluorescent genetically encoded pH indicator, named ‘pHerry’, in the presynaptic cytosol revealed acid efflux following nerve activity to be greater than that predicted from measurements of the intrinsic rate of acid efflux. Analysis of activity‐induced acid transients in terminals deficient in either endocytosis or exocytosis revealed an acid efflux mechanism reliant upon synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Pharmacological and genetic dissection in situ and in a heterologous expression system indicate that this acid efflux is mediated by conventional plasmamembrane acid transporters, and also by previously unrecognized intrinsic H+/Na+ exchange via the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter (DVGLUT). DVGLUT functions not only as a vesicular glutamate transporter but also serves as an acid‐extruding protein when deposited on the plasmamembrane.

Keywords: ion transport, motor nerve terminal, pH regulation

Key points

Intracellular pH regulation is vital to neurons as nerve activity produces large and rapid acid loads in presynaptic terminals.

Rapid clearance of acid loads is necessary to maintain control of neurotransmission, but neuronal acid clearance mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Glutamate is loaded into synaptic vesicles via the vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT), a mechanism conserved across phyla, and this study reports a previously unknown role for VGLUT as an acid‐extruding protein when deposited in the plasmamembrane during exocytosis.

The finding was made in Drosophila (fruit fly) larval motor neurons through a combined pharamacological and genetic dissection of presynaptic pH homeostatic mechanisms.

A dual role for VGLUT serves to integrate neuronal activity and pH regulation in presynaptic nerve terminals.

Abbreviations

- AE

anion exchanger

- AF568

Alexa Fluor 568‐dextran

- BafA1

bafilomycin A1

- DVGLUT

Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter

- Dyngo‐4a

3‐hydroxy‐N‧‐[(2,4,5‐trihydroxyphenyl)methylidene]naphthalene‐2‐carbohydrazide

- EB

Evans Blue

- EIPA

5‐(N‐ethyl‐N‐isopropyl)amiloride

- GEpHI

genetically encoded pH indicator

- HL3.1

haemolymph‐like solution 3.1

- LGA

l‐glutamic acid

- MN

motorneuron

- MN1‐Ib

type‐1 ‘big’ motorneuron boutons on muscle 1

- MN13‐Ib

type‐1 ‘big’ motorneuron boutons on muscle 13

- NHE

Na+/H+ exchanger

- NMJ

neuromuscular junction

- OGB

Oregon Green BAPTA‐1‐dextran

- pHcyto

cytosolic pH

- PM

plasmamembrane

- PMCA

plasmamembrane Ca2+‐ATPase

- ROI

region of interest

- SE‐pH

Super‐Ecliptic pHluorin

- SV

synaptic vesicle

- Syn‐pH

synapto‐pHluorin

- TetxIMP

inactivated tetanus toxin light chain

- TetxLC

tetanus toxin light chain

- vATPase

vesicular H+ ATPase

- VGLUT

vesicular glutamate transporter

Introduction

Neuronal activity generates large cytosolic pH (pHcyto) transients in presynaptic terminals and such transients are likely to influence mechanisms underlying neurotransmitter release (Nachshen & Drapeau, 1988; Zhang et al. 2010; Caldwell et al. 2013; Rossano et al. 2013). Minute changes in pHcyto can influence presynaptic processes such as voltage‐gated Ca2+ channel gating (Tombaugh & Somjen, 1997), endocytosis (Ybe et al. 1998), synaptic vesicle (SV) filling (Goh et al. 2011), cytosolic Ca2+ buffering (Krizaj et al. 2011), and both Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent kinase II (Smith et al. 1992) and cyclic‐AMP‐based (Green & Gillette, 1988) forms of synaptic plasticity. pHcyto in quiescent neurons is set by the equilibrium between standing acid influx and efflux. Neuronal activity, however, results in enhanced acid influx, primarily due to electroneutral H+/Ca2+ exchange across the plasmamembrane Ca2+‐ATPase (PMCA) as it clears cytosolic Ca2+ (Trapp et al. 1996; Schwiening & Willoughby, 2002; Rossano et al. 2013). pH homeostasis would be well served if nerve activity triggered acid efflux to offset acid influx.

Nerve activity may enhance acid efflux in many ways. Standing efflux mechanisms might be directly enhanced by decreasing pHcyto (Seidler et al. 1994; Leem et al. 1999) or through intracellular signalling linked to Ca2+ entry. For example, anion exchangers (AEs) are known to be modulated by Ca2+/calmodulin (Tosco et al. 2002). Also, various mammalian Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs) are modified by Ca2+‐dependent kinases and protein kinase A and C pathways (Kandasamy et al. 1995; Chu et al. 1996; Vila‐Petroff et al. 2010). Finally, but perhaps most significantly, activity‐induced acid efflux could be mediated by translocation of acid extruders, such as the vesicular H+ ATPase (vATPase), from intracellular compartments to the plasmamembrane (PM), as described for cholinergic mouse motorneuron (MN) terminals (Zhang et al. 2010). While mammalian NHE5 (Lukashova et al. 2013), NHE6 and NHE9 (Hill et al. 2006) are present on intracellular membranes in neurons, there are no reports of NHE translocation to the PM during nerve activity (Goh et al. 2011).

Whether activity‐induced acid efflux occurs at glutamatergic nerve terminals is unknown, but Drosophila glutamatergic MN terminals represent a tractable system for investigation. vATPases are present in these terminals and may extrude acid when deposited on the PM. Drosophila NHE (Giannakou & Dow, 2001) and AE (Romero et al. 2000; Dubreuil et al. 2010) expression patterns have only been grossly characterized. Vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUTs) have not been previously implicated in pHcyto homeostasis but a recent report of VGLUT1 cation/H+ exchange activity in mammalian SVs (Preobraschenski et al. 2014) led us to speculate that VGLUTs contribute to acid efflux.

VGLUTs transport glutamate into vesicles using the electrical portion (ΔΨH+) rather than the chemical portion (ΔpH) of the electrochemical proton gradient (ΔμH+) (Maycox et al. 1988; Omote et al. 2011), and most models of VGLUT bioenergetics suggest VGLUTs are coupled to cation/H+ exchangers (Goh et al. 2011; Preobraschenski et al. 2014) or a Cl− shunt (Schenck et al. 2009). While these mechanisms have never been validated beyond in vitro preparations, H+/cation exchange by VGLUT may provide a novel acid efflux mechanism when VGLUTs are deposited on the PM during SV exocytosis and exposed to the strong PM electrochemical Na+ gradient (ΔμNa+).

In this study, enhanced activity‐induced acid transients under exocytotic blockade suggest that Drosophila MN terminals usually extrude acid through the translocation of vesicular acid extruders to the PM. While translocation of the vATPase accounts for some acid efflux, pharmacological and genetic tools revealed a portion of the efflux is mediated directly by the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter (DVGLUT). This is the first report of pHcyto modulation in situ by a VGLUT in any cell. Expression of DVGLUT in Xenopus oocytes revealed intrinsic Na+/H+ exchange, which marks the first description of ion transport by DVGLUT. Modulation of activity‐induced pHcyto transients by DVGLUT though Na+/H+ exchange at the PM demonstrates novel integration of pHcyto, vesicular recycling, glutamate loading and [Ca2+]cyto in presynaptic terminals.

Methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not necessary for Drosophila studies. Xenopus laevis were housed and cared for in accordance and approval of the Institutional Care and Use Committees of the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine (protocol A27815).

Design and cloning of a pseudo‐ratiometric GEpHI

The genetically encoded pH indicator ‘pHerry’ was constructed by fusing the cDNA of Super‐Ecliptic pHluorin (SE‐pH), a proven pH‐sensitive green fluoresecent protein (470 nm ex./530 nm em.) (Miesenbock et al. 1998), with that of mCherry, a red fluorescent protein (556 nm ex./640 nm em.) that is pH‐insensitive in a physiological pH range (pKa < 4.5) (Shaner et al. 2004). A 17 amino acid linker sequence from ClopHensor (Arosio et al. 2010) was cloned into a pUC57 vector using BamHI and HindIII restriction sites. The cDNA of SE‐pH (from a GM8 plasmid supplied by Gero Miesenbock, University of Oxford, UK) was ligated to the 5‧ end of the linker and mCherry (Warren et al. 2010) was ligated to the 3‧ end using NotI/BamHI and HindIII/KpnI respectively. The entire pHerry cDNA was then ligated into the pJFRC14 expression vector using BglII/KpnI restriction enzymes. pcDNA3‐ClopHensor was a gift from Daniele Arosio (Centre for Integrative Biology, University of Trento, Italy; Addgene plasmid no. 25938). pcDNA3.3_mCherry was a gift from Derrick Rossi (Harvard Stem Cell Institute, USA; Addgene plasmid no. 26823)

Generation of flies expressing pHerry

pHerry cDNA within the pJFRC14 expression vector (Pfeiffer et al. 2010) was injected into w1118 Drosophila embryos by Rainbow Transgenic Flies (Newbury Park, CA, USA). UAS‐pHerry flies were then balanced and marked with TM6, Tb[+] (Craymer, 1984).

Fly stocks and husbandry

The w1118 strain (stock obtained from Nancy Bonini, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA) was used as a wild‐type control. Transgenes were expressed in MNs under the control of the GAL4/UAS system (Brand & Perrimon, 1993). All imaging of pHerry in type Ib MN terminals on muscle 13 was performed by driving UAS‐pHerry in larval MNs with a single copy of the pan‐neuronal P{nSyb‐GAL4} driver, hereby referred to as nSyb‐GAL4. A single copy of the P{eve‐GAL4.RRa} driver, hereby referred to as RRa‐GAL4 (Baines et al. 1999; Fujioka et al. 2003), was used to drive expression of each UAS‐transgene in Is/Ib terminals of muscle fibres 1 and 2. In such experiments imaging was performed exclusively on Ib terminals of muscle fibre 1. nSyb‐GAL4 and RRa‐GAL4 lines were respectively obtained from Dr Hugo Bellen (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA) and Dr Miki Fujioka (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Optical monitoring of endocytosis was achieved by expressing synapto‐pHluorin (Syn‐pH, a fusion of SE‐pH to synaptobrevin‐2) (Poskanzer et al. 2003) in MN terminals by driving two copies of UAS‐syn‐pH with two copies of the P{Appl‐GAL4.G1a} driver, hereby referred to as Appl‐GAL4 (Torroja et al. 1999). UAS‐Syn‐pH flies and Appl‐GAL4 flies were obtained from Gero Miesenbock and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Centre (Stock no. 32040; Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA), respectively. Flies expressing tetanus toxin light chain (UAS‐TetxLC) and inactivated tetanus toxin light chain (UAS‐TetxIMP) were obtained from Dr Sean Sweeney (University of York, UK) (Sweeney et al. 1995). Flies harbouring a deficient DVGLUT allele (dvglut1), a DVGLUT hypomorphic allele (dvglut2) and UAS‐dvglut were obtained from Dr Richard Daniels and the DiAntonio lab (Washington University, St Louis, MO, USA) (Daniels et al. 2004, 2006).

Flies were raised on standard medium with dry yeast at 23°C, except flies with the temperature‐sensitive dynamin mutation shibire (shiTS1), which were raised at 18°C (van der Bliek & Meyerowitz, 1991).

Solutions and chemicals for Drosophila larval live‐imaging

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise noted. Nominally HCO3 −/CO2‐free modified haemolymph‐like solution 3.1 (HL3.1) (Feng et al. 2004) buffered with 19 mM BES containing 0 mM NaHCO3 and 2 mM Ca2+ at pH 7.3 was used in all Drosophila live‐imaging experiments to avoid the unpredictable consequences of out‐of‐equilibrium buffering on calculations of acid flux as previous data suggest that HCO3 −/CO2‐derived buffering does not achieve equilibrium over the time course of rapid acid transients in Drosophila MN terminals (Rossano et al. 2013). Solutions containing NH4Cl were created by equilimolar replacement of NaCl. l‐Glutamic acid (7 mM; LGA, Cat. No. G1626; Sigma‐Aldrich) was added to all solutions to desensitize post‐synaptic glutamate receptors and minimize imaging artifacts created by muscle contraction.

Stock solutions of 5 mM bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) (Cat. No. sc‐201550; Santa‐Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), 20 mM nigericin (Cat. No. N7143; Sigma‐Aldrich), 100 mM 5‐(N‐ethyl‐N‐isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA) (Cat. No. A3085; Sigma‐Aldrich) and 100 mM 3‐hydroxy‐N‧‐[(2,4,5‐trihydroxyphenyl)methylidene]naphthalene‐2‐carbohydrazide (Dyngo‐4a) (Harper et al. 2011; Gagliardi et al. 2014) (Cat. No. ab120689; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) were made in Pluronic F‐127 (20% Pluronic in DMSO; Cat. No. P3000MP; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A stock of 50 mM Evans Blue (EB) (Cat. No. E2129; Sigma‐Aldrich) was made in water. All drugs were diluted in modified BES‐buffered HL3.1 for use on the day of experiments. In all experiments in which drugs were applied in DMSO, DMSO was added to produce a final concentration of 0.1%. Vehicle control was 0.1% DMSO in all experiments. To ensure adequate access of BafA1, EIPA, EB and Dyngo‐4a to transporters on the membrane of the entire readily releasable vesicle pool and the PM, preparations were incubated in drug for 10 min, stimulated at 30 Hz for 6 min, and then incubated in drug for an additional 10 min prior to imaging (Macleod et al. 2004). Final drug concentrations were: 1 μM BafA1, 50 μM EIPA, 10 μM EB, 20 μM nigericin and 100 μM Dyngo‐4a

Preparation of Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction

Wandering 3rd instar Drosophila larvae were collected and prepared for nerve stimulation as previously described (Rossano et al. 2013). Briefly, larvae were fillet‐dissected and a loop of the segmental nerve to segment A4 was drawn into a glass suction pipette and stimulated with pulses sufficient to elicit action potentials (2.4 V at 300 μs duration). Male larvae were used for shiTS1 experiments and their controls; female larvae were used in all other cases.

A consistent ‘depletion’ protocol was used to deplete all SVs from MN terminals in shiTS1 larvae and their controls. The segment nerve was stimulated at 30 Hz for 6 min at a non‐permissive (34°C) temperature in 2 mM Ca2+ saline. Electron microscopy has demonstrated that this protocol, relying on nerve stimulation, will fuse all SV membranes with the PM in larval MN terminals (Macleod et al. 2004).

Preparations exposed to drugs were stimulated with a control train (when indicated), incubated with drug for 15 min, exposed to the depletion protocol and incubated for another 15 min before experimental stimulation/NH4Cl pre‐pulse to ensure both PM and vesicular proteins were exposed to drug treatments.

For experiments which required rapid solution, substitution flow was controlled by an eight‐channel valve‐gated gravity‐driven perfusion system (VC3 and VM8 by ALA Scientific Instruments, Farmingdale, NY, USA) synchronized to stimulation and image acquisition by a MASTER8 pulse controller. An optical fluid level sensor coupled to a vacuum‐mediated outflow reservoir (LeveLock LL‐2, ALA Scientific Instruments) was used to maintain flow rate at ∼6 ml min–1 to achieve complete bath exchange approximately every 4 s. In experiments which required temperature control, a Peltier heating plate connected to a regulated DC power supply (Pyramid, Brooklyn, NY, USA) was introduced to the fluid inflow tube before the dissecting chamber and a thermister was inserted in the bath to continuously monitor bath temperature.

Loading a synthetic Ca2+ indicator in Drosophila MN terminals

Oregon Green BAPTA‐1‐dextran (OGB, Cat. No. O‐6798, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), a 10,000 MW dextran‐conjugated Ca2+ indicator (K d ∼1015 nM in situ), was forward‐filled into MN terminals as previously described (Macleod et al. 2002; Rossano & Macleod, 2007). Alexa Fluor 568‐dextran (AF568, MW = 10,000, Cat. No. D‐22912, Molecular Probes) was mixed with OGB prior to loading to serve as a spectrally distinct loading control, and to correct for movement.

Wide‐field imaging

Wide‐field microscopy was performed on two live‐imaging workstations. Common to both workstations used for imaging either SE‐pH/mCherry or OGB/AF568 was a 60× (0.9 NA) water immersion objective, EMCCD cameras and emission beam splitters configured to allow acquisition of separate emission wavelengths. The first workstation consisted of an Olympus (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) BX51WI microscope fitted with an Olympus 60× (0.9 NA) water immersion objective. A Lumen Dynamics (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) X‐Cite XLED1 LED excitation unit with GYX (540–600 nm) and BDX (450–495 nm) modules was used to supply excitation light which was then further filtered with a dual‐band pass 470/556 nm filter. Images were captured with an Andor Technology (Belfast, Northern Ireland) EMCCD camera (DV887). A Cairn Instruments (Faversham, UK) Optosplit II emission beam‐splitter was placed before the camera for dual‐emission wavelength imaging. Simultaneous imaging of the mCherry (ex./em. 556/640 nm) and SE‐pH (ex./em. 480/530 nm) components of pHerry was achieved using a primary 500/530 nm dual‐band dichroic mirror in the microscope housing, a secondary 600 nm dichroic mirror mounted in the emission beam‐splitter, and 512/25 and 660/20 nm emission filters in the beam‐splitter. The mCherry signal was collected at a wavelength red‐shifted from the emission maximum to avoid contamination of the signal from the SE‐pH emission signal. Image acquisition was 5 Hz (five image pairs per second). The imaging system was controlled through a Dell PC running Andor iQ software (ver. 2.7.1). The second imaging workstation consisted of a Nikon (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) Eclipse FN1 microscope fitted with an Olympus 60× (0.9 NA) water immersion objective. Excitation wavelengths were selected from a Lumencor (Beaverton, OR, USA) Spectra X LED light engine with 470 and 555 nm modules. A 455/525/605/705 nm quad‐band dichroic mirror was mounted in the microscope housing. For pHerry imaging, excitation was achieved by alternating activation of the 470 and 555 nm LED modules and emitted light was passed to an Andor TuCam emission beam‐splitter/dual camera adaptor fit with a secondary 580 nm dichroic and 525/50 and 617/73 nm emission clean‐up filters. The two emission signals then passed to separate Andor DU897 EMCCD cameras. Image acquisition was 90 ms per channel to produce an overall acquisition rate of 5 Hz. The imaging system was controlled through a Dell PC running Nikon Elements software (ver. 4.30.02).

Imaging of OGB/AF568‐loaded preparations was performed on the Nikon workstation using the same filters and parameters as the pHerry imaging described above. Syn‐pH imaging was performed on the Nikon workstation using the 470 nm LED module, a 450–490 nm excitation clean‐up filter, a 495 nm dichroic mirror, a 500–550 nm emission filter and a single Andor DU897 EMCCD camera. Image acquisition rate was 5 Hz.

Filters and dichroic mirrors were obtained from Chroma Technology (Bellows Falls, VT, USA) or Semrock (Lake Forest, IL, USA). All imaging was performed at room temperature (∼23°C) unless otherwise noted. Live imaging was of MN terminals of axons innervating muscle 13 or muscle 1 of abdominal segment 4 with type‐Ib ‘big’ boutons (MN13‐Ib or MN1‐Ib as noted in individual experiments), with regions of interest (ROIs) drawn around at least three non‐terminating boutons.

Image analysis and data processing

Background subtraction was performed in all images using a background ROI in either Andor iQ or Nikon Elements. On the Andor workstation the SplitField plugin was used to compile interleaved stacks of the SE‐pH and mCherry fluorescence signals from pHerry. Data from the Nikon workstation were exported directly to Microsoft Excel 2007. Ratiometric analysis of fluorescent signals was performed numerically in Microsoft Excel.

In situ calibration of pHerry

pHerry was calibrated in situ using the nigericin/K+ method (Thomas et al. 1979) adapted to Drosophila MN terminals as previously described (Rossano et al. 2013). Larvae were fillet dissected and the segmental nerves were cut from the ventral ganglion. Calibration solution contained 20 μM nigericin, 130 mM KCl, 5 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 5 mM trehalose, 5 mM sucrose, 0 mM CaCl2 and 7 mM LGA to equilibrate intracellular and extracellular [H+] while minimizing muscle contraction. These solutions were titrated to pH ∼5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8 and 9 through the addition of HCl and NaOH. Calibration solutions were buffered with zwitterionic buffers suited to the desired pH (MES for pH 5.5–6, BES for pH 6.5–7.5 and TAPS for pH 8–9). Preparations were incubated for 10 min in the pH ∼ 7 solution and then perfused with each of the calibration solutions of pH 5.5–7.5 in a pseudo‐randomized order before being exposed to the pH ∼ 8 and 9 solutions to achieve the maximum fluorescence ratio of the SE‐pH to mCherry fluorescence. A Boltzmann curve was then fit to the scatter plot of the imposed pH versus fluorescence ratio values. This calibration procedure was conducted separately on each live imaging workstation. No comparisons were made between data collected on the separate imaging workstations.

Calculation of net molar acid flux in Drosophila MN terminals

Net molar acid flux (JH+, mm s–1) during nerve stimulation was calculated according to eqns (1)–(3) which describe theoretical relationships between total buffering power (βT), intrinsic (non‐bicarbonate‐derived) buffering power (βi), bicarbonate‐derived buffering power (βb) and JH+ (Chesler, 1990; Svichar et al. 2011) as well as the previously determined empirical dependence of βi on pHcyto in Drosophila MN terminals (Rossano et al. 2013). All solutions used in live‐imaging were nominally HCO3 −‐free and thus βb = 0 mM and βT = βi. Whenever net molar acid flux was calculated for a time interval, βT over the interval was assumed to be βi corresponding to pHcyto at the beginning of the interval. In our calculations of JH+ we assumed that the previously described relationship between pHcyto and βi holds for both MN13‐Ib and MN1‐Ib MN terminals. However, when comparing JH+ between groups, when possible, we calculated the JH+ through the pHcyto range in which the activity‐induced transients of the groups overlapped in order to minimize the effects of changes in βi and the pH dependence of acid flux upon our comparisons.

Comparisons of JH+ following withdrawal of a 40 mM NH4Cl pre‐pulse (Boron & De Weer, 1976) were conducted by fitting single exponential curves to the recovery phase of raw pHcyto traces and then using these exponential fits to plot JH+ as a function of pHcyto every 0.05 pH units over the range of pHcyto displayed in the original raw pHcyto trace. A linear function was applied to the points from the JH+/pHcyto plot which fell in a pHcyto range common to all experimental groups being compared but was also at least 0.3 pH units lower than the resting pHcyto. This latter stipulation was necessary as JH+ approaches 0 mM s–1 as pHcyto returns to the resting pHcyto, which in turn produces a skewed and non‐linear relationship between JH+ and pHcyto near the resting pHcyto. 0.30 pH units below resting pHcyto was chosen as this restriction produced R 2 ≥ 0.96 when a linear function was applied to the JH+/pHcyto plots. The slopes (mM pH units−1 s−1) of the linear fits from the data in each group were then compiled and compared as indicated. For experiments in which acid loading was produced by nerve stimulation, the single‐exponential recovery time constant (τrec, s) of the raw pHcyto trace was used as a proxy for JH+. These experiments displayed little overlap of pHcyto between the control and experimental conditions in the recovery phase that was sufficiently removed from resting pHcyto to produce a reliable linear relationship between JH+ and pHcyto.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Preparation of cRNA for DVGLUT expression in oocytes

The cDNA of DVGLUT was inserted into the pGEMHE Xenopus laevis expression vector (Romero et al. 1998). The plasmid was linearized with NotI restriction enzyme and transcribed into cRNA in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase and mMESSAGE mMACHINE kits (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA).

Oocyte electrophysiology using H+ and Na+‐selective microelectrodes

Xenopus laevis oocytes were dissociated with collagenase and injected with 50 nl of water or a solution containing cRNA of DVGLUT at 0.2 ng nl–1 (10 ng per oocyte) using a Nanoject‐II injector (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA, USA) as described previously (Romero et al. 1998). Oocytes were incubated at 16°C in ND96 saline solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.5) and studied 2–4 days after injection.

To measure pHcyto or [Na+]cyto of oocytes, H+ or Na+‐selective micro‐electrodes were prepared with an H+ ionophore I‐mixture B ion‐selective resin (Fluka Chemical, Ronkonkoma, NY, USA) or an Na+ ionophore cocktail A (Fluka), respectively, as described previously (Romero et al. 1998; Ito et al. 2014). pHcyto or [Na+]cyto was measured as the difference between the pH or Na+ electrode and a KCl voltage electrode impaled into the oocyte. The membrane potential (V m) was measured as the difference between the KCl microelectrode and an extracellular calomel. pH electrodes were calibrated using pH 6.0 and 8.0 buffers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), followed by a point calibration in ND96 (pH 7.5). Na+ electrodes were calibrated with 10 and 100 mM NaCl, and the specificity was checked using 100 mM KCl, followed by a point calibration in the perfusion chamber with ND96 (96 mM Na+).

The oocyte was held on a nylon mesh in a chamber and perfused with solution. V m and pHcyto or [Na+]cyto were constantly monitored and recorded at 0.4 Hz. Na+‐free (0 mM Na+) solutions were prepared by substituting NaCl with choline chloride. Osmolarity and pH of all media were adjusted to ∼200 mosmol l–1 and 7.5, respectively. In experiments in which oocytes were treated with EB, oocytes were incubated in ND96 supplemented with 20 μM EB for 10–20 min prior to the experiment and 20 μM EB was added to all solutions used during the experiment.

Statistical analysis and data presentation

SigmaPlot (version 10.0; Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA) and GraphPad Prism (Version 5; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) software were used for statistical analysis and curve fitting. One‐way ANOVA, repeated‐measures ANOVA, and two‐way Student's t tests were used as indicated for individual experiments. Holm‐Sidak post hoc tests for used for pairwise comparisons following ANOVA tests. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at α‐values of P < 0.050. Figures were generated in SigmaPlot or GraphPad Prism software and imported to Illustrator CS5.1 for panel assembly and labelling. Unless noted otherwise, variance indicated in plots is the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

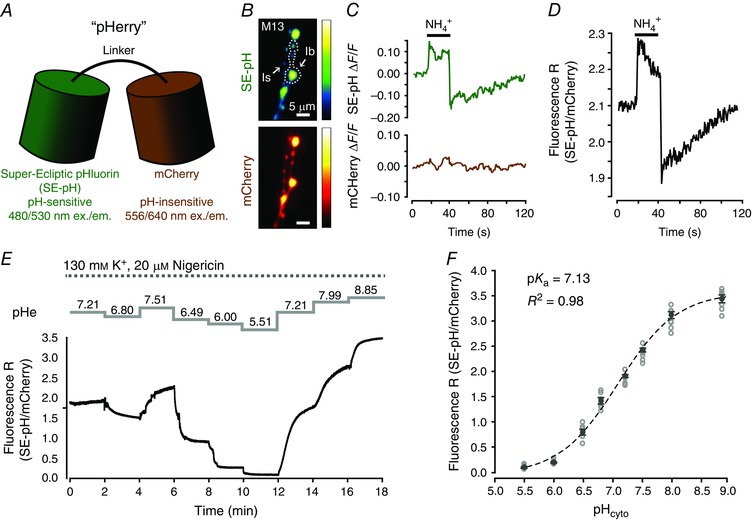

‘pHerry’ reports cytosolic pH in motorneuron terminals in situ

A pseudo‐ratiometric GEpHI was essential in this study as it allowed for measurements of resting pHcyto and activity‐induced changes in pHcyto to be compared across genotypes and experimental conditions. ‘pHerry’ was based upon a previously described chimera of SE‐pH and mCherry (Koivusalo et al. 2010), modified in this study with an intervening linker to prevent interaction between the fluorophores (Fig. 1 A). pHerry expresses well in the cytosol of Drosophila MN terminals and shows no signs of aggregation when single copies of UAS‐pHerry are driven with single copies of GAL4 drivers (Fig. 1 B). pHerry is photostable and shows the predicted response in fluorescence intensity during a 20 mM NH4Cl pre‐pulse, i.e. the pH‐sensitive SE‐pH signal rising during the pulse and falling immediately following NH4Cl withdrawal while the pH‐insensitive mCherry signal remained constant throughout the procedure (Fig. 1 C, D). The pHerry fluorescence ratio produced repeatable values in separate calibration exercises (pK a = 7.13; n = 7 larvae in each calibration) (Fig. 1 E, F) which indicates the ratio reports absolute pHcyto of nerve terminals in situ.

Figure 1. pHerry ratiometrically reports cytosolic pH of nerve terminals in situ .

A, schematic representation of the pHerry pH sensor. B, wide‐field epifluorescence images of the SE‐pH and mCherry components of pHerry expressed in the cytosol of M13‐Ib and MN13‐Is terminals. C, representative trace of the relative change in fluorescence (ΔF/F) of the SE‐pH and mCherry components of pHerry from MN13‐Ib terminals in response to a 20 s pulse of 20 mM NH4Cl. D, representative trace of the fluorescence ratio change of pHerry in response to a 20 s pulse of 20 mM NH4Cl in the same MN13‐Ib terminals as in C. E, representative trace of the changes in the pHerry fluorescence ratio from M13Ib terminals as the preparation was sequentially exposed to calibration solutions buffered to the indicated pH values in the presence of 20 μM nigericin and 130 mM K+. F, calibration curve of the pHerry fluorescence ratio to the imposed pHcyto values constructed from experiments in E. n = 7 larvae with each exposed to all eight pHcyto values. Open grey circles are individual measurements, black closed circles and bars are mean ± SEM. Black line is Boltzmann curve fit to the individual points in grey.

Intrinsic acid extrusion from Drosophila MN terminals is pH dependent but this mechanism does not account for the acid efflux rate observed following activity‐induced acid transients

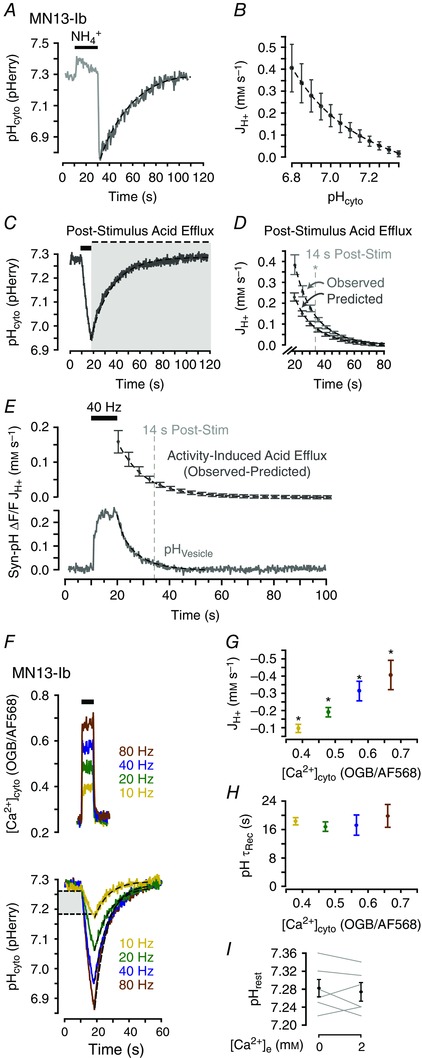

The pH dependence of intrinsic acid extrusion in MN13‐Ib terminals was characterized to determine if acid efflux during and following nerve activity was greater than that predicted by intrinsic acid efflux. Acid extrusion is pH dependent in many cell types, and as nerve activity in Drosophila MN terminals induces large acid loads, activation of intrinsic acid extrusion by the drop in pHcyto alone could potentially account for the time course of re‐alkalization (Seidler et al. 1994; Leem et al. 1999). MN13‐Ib terminals were acid loaded with 40 mM NH4Cl pre‐pulses while pHcyto was monitored with pHerry (Fig. 2 A). This method allows for reproducible acid loading of cellular preparations independent of Ca2+ and electrical stimulation as application of NH4Cl initially produces an intracellular alkalinization through entry of uncharged NH3 followed by a dose‐ and time‐dependent acid load when NH4Cl is removed and NH3 exits while leaving behind previously bound H+ (Boron & De Weer, 1976). Recovery of pHcyto following acid loading followed the time course of a single exponential equation (R 2 > 0.95 in six larvae). Intrinsic acid efflux was revealed to be inversely correlated with pHcyto by calculating net molar acid flux during the recovery phase and plotting JH+ as a function of pHcyto (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2. Enhanced acid extrusion following activity‐induced cytosolic acid transients follows a time course similar to that of synaptic vesicle membrane endocytosis.

A, representative trace of pHcyto after a 20 s 40 mM NH4Cl pulse in MN13‐Ib terminals of w1118 larvae. B, net molar acid flux (JH+, mM s–1) after NH4Cl as a function of pHcyto. JH+ computed from the acid recovery phase (shown in A). Mean ± SEM, n = 6 larvae. C, representative trace of a nerve stimulation‐induced acid transient in MN13‐Ib terminals (40 Hz, 8 s). Grey box highlights post‐stimulus acid efflux. D, average JH+ every 1 s during the acid recovery phase (observed: recovery phase of pHcyto transients in C) and predicted intrinsic JH+ at mean pHcyto in each 1 s interval (calculated from B). Mean ± SEM, n = 6 larvae. Vertical line indicates time after stimulation at which values of observed and predicted flux are no longer significantly different (P > 0.050, unpaired Student's t test). E, activity‐induced JH+ (upper panel) following stimulation [calculated as (observed−predicted) acid flux in D]. Mean ± SEM, n = 6 larvae from D. Time course of endocytosis (lower panel, relative fluorescence change in Syn‐pH, average trace of n = 7 larvae). F, activity‐induced [Ca2+]cyto (representative traces) and pH (averaged traces, n = 6 larvae at each frequency) transients from 8 s action potential trains. Light grey box indicates the overlapping pHcyto range within which JH+ was calculated. G, quantification of mean JH+ during stimulation as a function of peak [Ca2+]cyto. Mean ± SEM, n = 6 larvae with values pooled by stimulation frequency and plotted to OGB/AF568 fluorescence ratio, * P < 0.050, repeated measures one‐way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc test. H, τrec of acid extrusion phase as a function of peak [Ca2+]cyto. Data plotted as in G; P > 0.050, repeated measures one‐way ANOVA. I, quantification of resting pHcyto before and after addition of 2 mm Ca2+ to Ca2+‐free HL3.1. Mean ± SEM. P > 0.050, paired Student's t test, n = 6 larvae. Dashed lines in A–C, E and F are single exponential curves.

Acid efflux following nerve activity‐induced cytosolic acid transients was determined to be greater than that predicted by the pH dependence of intrinsic acid extrusion. Here, nerve activity was imposed by trains of electrical impulses applied to the nerve and these impulses allow direct control of the frequency of presynaptic action potentials. JH+ was calculated as a function of time in the post‐stimulation acid efflux phase and compared to the efflux predicted by quantification of intrinsic acid extrusion at the corresponding pHcyto (Figs 2 C and 1 D). In all cases the calculated (observed) efflux was larger than predicted and pooled analysis revealed this difference remained significant until 14 s after stimulation (P < 0.050, unpaired Student's t test). Predicted efflux was subtracted from the observed efflux and the resulting ‘activity‐enhanced’ acid efflux was plotted as a function of time following stimulation. The time course of the enhanced acid efflux (τ = 14.6 ± 1.3 s, Fig. 2 E top panel) was slightly prolonged from that of SV retrieval from the PM as measured by tracking vesicle re‐acidification with Syn‐pH (τ = 5.8 ± 0.5 s, n = 7 larvae) (Fig. 2 E lower panel).

Previous quantifications of activity‐induced acid transients in Drosophila MN terminals revealed acid loading scales with the frequency and duration of stimulation but the recovery time course remains constant (Caldwell et al. 2013; Rossano et al. 2013). These results suggest acid efflux scales in proportion to the initial acid load as would be expected if acid efflux were proportionally enhanced by neuronal activity. Characterization of pHcyto and [Ca2+]cyto transients in response to different stimulation frequencies (Fig. 2 F) confirmed both the positive correlation between JH+ and stimulation frequency (Fig. 2 G; F 3,15 = 7.614, P = 0.003 by repeated measures one‐way ANOVA, P < 0.050 between all groups by Holm–Sidak post hoc test) and the consistency of τrec even with increasing stimulation frequency (Fig. 2 H; F 3,15 = 0.295, P = 0.828 by repeated measures one‐way ANOVA; n = 6 larvae). However, resting pHcyto was independent of extracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]e), as addition of 2 mM Ca2+ to Ca2+‐free modified HL3.1 saline did not change resting pHcyto in MN13‐Ib terminals (P = 0.497, paired Student's t test; n = 6 larvae) (Fig. 2 I).

Acid extrusion from MN terminals is inhibited by blockade of evoked exocytosis and enhanced by prolonged fusion of SVs at the PM

The similar time courses of activity‐enhanced acid efflux and endocytosis suggest SV trafficking and PM fusion may modulate acid transients. Drosophila glutamatergic MN terminals are particularly well suited to further elucidate this acid efflux mechanism as spontaneous and evoked vesicular fusion are well characterized at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ) (Jan & Jan, 1976; Kuromi & Kidokoro, 2005). Importantly, there are existing genetic tools for manipulating SV fusion.

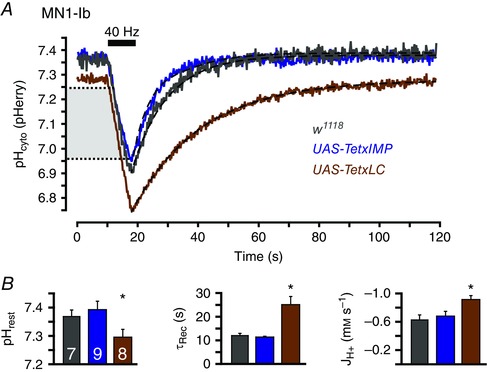

The role of evoked SV exocytosis in shaping cytosolic acid transients was examined by comparing activity‐induced acid transients in w1118 larvae and larvae in which expression of TetxLC was driven in MNs. TetxLC expression in Drosophila MN terminals results in complete blockade of evoked exocytosis and a modest decrease in the frequency of spontaneous vesicle fusion (Sweeney et al. 1995). No larvae survived to 3rd instar when TetxLC was expressed pan‐neuronally, so TetxLC was expressed in a limited set of neurons using the RRa‐GAL4 driver. Under these conditions the only MN terminals consistently present and assessable were the type I ‘big’ terminals on muscle 1 (MN1‐Ib). Morphologically and functionally, larvae expressing TetxIMP were indistinguishable from w1118 control larvae. Blockade of evoked exocytosis by TetxLC expression had a significant impact on activity‐induced acid transients (Fig. 3 A). The resting pHcyto was not significantly different between w1118 (n = 7) and TetxIMP (n = 9) larvae but was decreased in TetxLC (n = 8) larvae (7.29 ± 0.03 as compared to 7.37 ± 0.02 and 7.39 ± 0.03; F 2,21 = 3.709, P = 0.042 by one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.001 by Holm–Sidak post hoc test). Absolute JH+ during activity was increased by the expression of TetxLC (–0.89 ± 0.05 mM s–1 as opposed to –0.60 ± 0.10 mM s–1 and –0.64 ± 0.10 mM s–1 in w1118 and TetxIMP larvae; F 2,21 = 26.904, P < 0.001 by one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.001 by Holm–Sidak post hoc test). Finally, τrec was prolonged in TetxLC larvae (24.8 ± 3.72 s as opposed to 12.0 ± 0.97 s and 11.1 ± 0.62 s in w1118 and TetxIMP larvae; F 2,21 = 11.873, P < 0.001 by one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.001 by Holm–Sidak post hoc test) (Fig. 3 B). Together, these data suggest that blockade of activity‐induced exocytosis of SVs impairs an activity‐enhanced acid efflux mechanism which persists for seconds following nerve stimulation.

Figure 3. Blockade of evoked exocytosis increases activity‐induced cytosolic acid loading and slows subsequent acid extrusion.

A, averaged traces of activity‐induced pHcyto transients in MN1‐Ib terminals of w1118 (n = 7 larvae), UAS‐TetxIMP (n = 9) and UAS‐TetxLC (n = 8) larvae. Stimulation (black bar) was 40 Hz for 8 s. Dashed lines are exponential curves. Light grey box indicates the overlapping pHcyto range within which JH+ during stimulation was calculated. B, quantification of resting pHcyto, τrec of acid extrusion phase (dashed lines in B) and mean JH+ during stimulation in the three genotypes. Mean ± SEM. * P < 0.050, one‐way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc test.

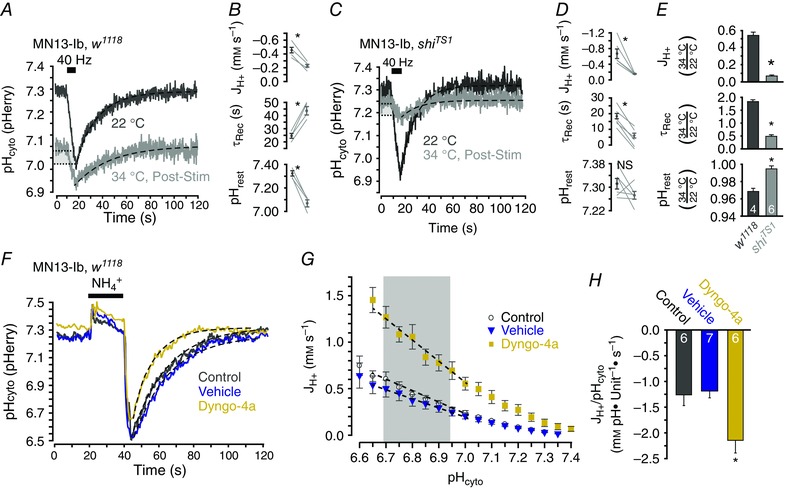

Given that loss of exocytosis decreased activity‐induced acid efflux, it follows that stabilization of SVs at the PM by inhibition of endocytosis could exaggerate the putative activity‐induced acid efflux. To this end, activity‐induced acid transients were examined in a temperature‐sensitive dynamin mutant shiTS1 (van der Bliek & Meyerowitz, 1991). Transients were compared between endocytosis‐deficient larvae and temperature matched controls. Both w1118 (n = 4) and shiTS1 (n = 6) larvae showed changes in activity‐induced acid transients when stimulated at the non‐permissive temperature of 34°C, subsequent to a stimulus protocol known to accumulate all SV membrane at the PM (Macleod et al. 2004) (Fig. 4 A, C). At the non‐permissive temperature resting pHcyto decreased from 7.31 ± 0.02 to 7.08 ± 0.03 (P = 0.003 by paired Student's t test) in w1118 larvae while τrec increased from 23.8 ± 1.72 to 43.5 ± 3.13 s (P = 0.002 by paired Student's t test) and the absolute activity‐induced JH+ decreased from –0.48 ± 0.05 to –0.25 ± 0.03 mM s–1 (P = 0.005 by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 4 B). In post‐depletion shiTS1 larvae, resting pHcyto was not significantly different at the non‐permissive temperature (7.31 ± 0.02 compared to 7.27 ± 0.01; P = 0.188 by paired Student's t test) but τrec was decreased (accelerated) from 17.9 ± 1.64 to 8.96 ± 1.62 s (P < 0.001 by paired Student's t test) and absolute JH+ was decreased from –0.60 ± 0.08 mM s–1 to –0.09 ± 0.02 mM s–1 (P = 0.007 by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 4 D).

Figure 4. Entrapment of synaptic vesicle membrane at the plasmamembrane attenuates activity‐induced cytosolic acid transients.

A, averaged activity‐induced pHcyto transients in MN13‐Ib terminals of w1118 larvae at 22°C and again 10 min after stimulation at 30 Hz for 6 min (‘depletion stimulation’) at 34°C (n = 4 larvae). B, quantification of JH+, τrec and resting pHcyto from A. C, averaged activity‐induced pHcyto transients in MN13‐Ib terminals of shiTS1 larvae at 22°C and again 10 min after depletion stimulation at 34°C (n = 6 larvae). D, quantification of JH+, τrec and resting pHcyto from C. E, ratios of resting pHcyto, τrec and JH+ at 22 and 34°C in w1118 and shiTS1 larvae (same data as B and D). Mean ± SEM. * P < 0.050, unpaired Student's t test. Data in A and C plotted as mean ± SEM. NS, not significant, * P < 0.050, paired Student's t test. Dashed lines in A and C are single exponential curves. Light grey boxes indicate the overlapping pHcyto range within which JH+ during stimulation was calculated. Stimulation (black bar) was 40 Hz for 8 s in A and C. F, representative pHcyto changes in response to a 20 s 40 mM NH4Cl pulse in MN13‐Ib terminals of w1118 larvae with no prior stimulation or drug application (control), after depletion stimulation in vehicle, and after depletion stimulation in Dyngo‐4a. Dashed lines are single exponential curves. G, JH+ following withdrawal of 40 mM NH4Cl as a function of pHcyto in untreated (control, n = 6), vehicle‐treated (n = 7) and Dyngo‐4a‐treated (n = 6) larvae. Mean ± SEM. Grey box indicates common pHcyto range for acid recovery. Dashed lines are linear functions. H, quantification of linear slope of JH+ as a function of pHcyto in pH range indicated in G. Mean ± SEM. * P < 0.050, one‐way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc test.

To determine the effects of SV membrane trapping at the PM and account for the effects of high temperature on w1118 controls, the data were analysed as the ratio of the values for resting pHcyto, τrec and JH+ determined at the non‐permissive temperature over those observed at the permissive temperature. These ratios were then compared between w1118 and shiTS1 larvae (Fig. 4 E). This analysis revealed that resting pHcyto was increased (P < 0.001 by unpaired Student's t test), τrec was decreased (P < 0.001 by unpaired Student's t test) and absolute JH+ was decreased (P < 0.001 by unpaired Student's t test) in shiTS1 larvae as compared to temperature‐matched w1118 larvae. These results again suggest the engagement of an acid efflux mechanism which is trafficked to the PM during vesicle exocytosis where it offsets acid influx during nerve activity and speeds acid clearance in the seconds after nerve activity.

The finding that genetic inhibition of dynamin and subsequent trapping of SVs at the PM enhanced acid efflux was corroborated by pharmacologically inhibiting dynamin with 100 μM Dyngo‐4a. Dynamin inhibitors are known to have off‐target effects at the Drosophila NMJ (Dason & Charlton, 2014) and thus we examined the effects of Dyngo‐4a (n = 6 larvae) and vehicle (n = 6 larvae) application on acid efflux following a 40 mM NH4Cl pre‐pulse rather than nerve stimulation (Fig. 4 F‐H). Larvae were incubated in Ca2+‐containing solutions with drug or vehicle and stimulated for 6 min at 30 Hz to fuse vesicular membrane at the PM. Preparations were then transferred to Ca2+‐free solutions for the NH4Cl pre‐pulse to minimize the influence of processes other than acid extrusion. Under these conditions Dyngo‐4a significantly increased acid efflux as compared to vehicle and control (n = 6 larvae) conditions (–2.14 ± 0.25, –1.18 ± 0.14 and –1.26 ± 0.21 mM pH units−1 s−1 respectively; F 2,16 = 7.228; P = 0.005 by one‐way ANOVA, P = 0.003 and 0.007 by Holm–Sidak post hoc test) (Fig. 4 G). These results indicate that prolonged retention of vesicular proteins at the PM increases cytosolic acid efflux through a Ca2+‐ and activity‐independent mechanism.

Both vesicular and PM H+ transporters regulate pHcyto in MN terminals at rest and following activity‐induced acid loads

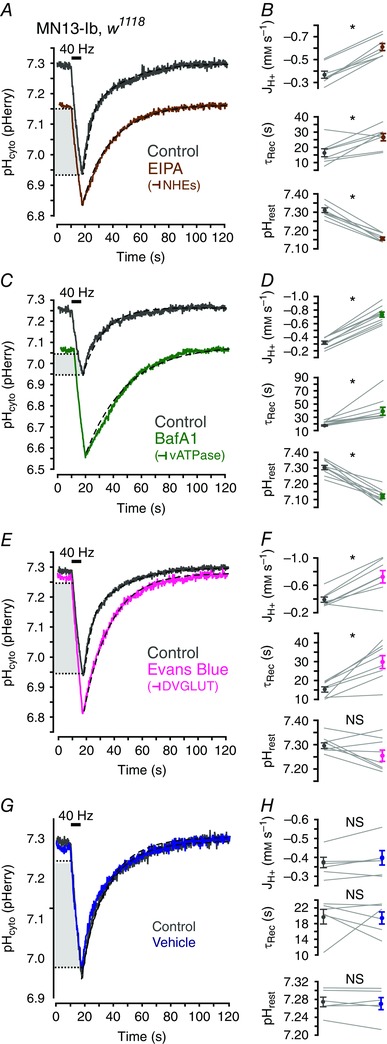

After determining that activity‐induced acid efflux was sensitive to evoked endocytosis and exocytosis, pharmacological inhibition of vesicular and PM acid transporters was conducted to further dissect this phenomenon. NHEs contribute pHcyto regulation in many cells, including Drosophila MNs (Giannakou & Dow, 2001; Caldwell et al. 2013), and treatment with 50 μm EIPA, a blocker of NHE activity, impaired clearance of acid loads from MN13‐Ib terminals following nerve stimulation (Fig. 5 A, B). Previous work demonstrates the vATPase can serve as an acid efflux mechanism in mouse MN terminals when translocated to the PM during exocytosis (Zhang et al. 2010). A homologous multi‐subunit vATPase exists in Drosophila and we predicted it may have a similar role in shaping acid transients (Dow, 1999). Indeed, we found that the vATPase inhibitor BafA1 at 1 μm radically altered activity‐induced acid transients (Fig. 5 C, D). DVGLUT is also found on SVs at the Drosophila NMJ (Daniels et al. 2004) and may be capable of H+ transport. As the sensitivity of DVGLUT to VGLUT inhibitors is not known, DVGLUT inhibition was attempted with the broad glutamate transporter inhibitor EB (10 μM) (Balcar et al. 1977; Roseth et al. 1998; Danbolt, 2001). EB increased absolute JH+ during stimulation and τrec but did not alter resting pHcyto (Fig. 5 E, F). Activity‐induced acid transients were not altered by application of vehicle control (n = 6 larvae; P > 0.120 for all variables by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 5 G, H). All pharmacological inhibitors produced results consistent with impairment of acid efflux mechanisms, which suggest that DVGLUT, the vATPase and NHEs all contribute to pHcyto regulation following activity‐induced acid loads in Drosophila MN terminals (see Table 1 for values and statistical analysis).

Figure 5. DVGLUT, NHEs and the vATPase all contribute to activity‐induced enhanced cytosolic acid efflux in presynaptic terminals.

A, averaged traces of activity‐induced pHcyto transients in MN13‐Ib terminals of w1118 larvae before and after depletion stimulation in 50 μM EIPA (n = 9 larvae). B, paired quantification (from A) of mean JH+ during stimulation, τrec and resting pHcyto in w1118 larvae before and after incubation in EIPA. C–H, data collected and represented as in A and B with incubation in 1 μM BafA1 (n = 10), 10 μm EB (n = 8) and vehicle (n = 6) as indicated. See Table 1 for values. Stimulation (black bar) was 40 Hz for 8 s in A, C, E and G. Dashed lines are single exponential curves. Light grey box indicates the overlapping pHcyto range within which JH+ during stimulation was calculated. Data in B, D, F and H are plotted as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.050, paired Student's t test.

Table 1.

Application of drugs which target plasmamembrane and vesicular acid transporters alters activity‐induced pHcyto acid transients in MN terminals

| Treatment | Value | Control (mean ± SEM) | Drug (mean ± SEM) | n | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pHrest | |||||

| EIPA | 7.30 ± 0.01 | 6.84 ± 0.02 | 8 | <0.001* | |

| BafA1 | 7.30 ± 0.01 | 7.12 ± 0.01 | 10 | <0.001* | |

| Evans Blue | 7.30 ± 0.01 | 7.26 ± 0.02 | 8 | 0.080 | |

| Vehicle | 7.28 ± 0.01 | 7.27 ± 0.01 | 6 | 0.610 | |

| τrec (s) | |||||

| EIPA | 16.4 ± 2.62 | 26.6 ± 2.37 | 8 | 0.011* | |

| BafA1 | 17.6 ± 1.00 | 39.2 ± 6.02 | 10 | 0.003* | |

| Evans Blue | 15.3 ± 1.42 | 29.8 ± 3.40 | 8 | 0.002* | |

| Vehicle | 19.8 ± 2.01 | 19.6 ± 1.95 | 6 | 0.948 | |

| JH+ (mM s–1) | |||||

| EIPA | −0.39 ± 0.03 | −0.64 ± 0.03 | 8 | <0.001* | |

| BafA1 | −0.27 ± 0.02 | −0.66 ± 0.03 | 10 | <0.001* | |

| Evans Blue | −0.39 ± 0.04 | −0.73 ± 0.10 | 8 | 0.004* | |

| Vehicle | −0.37 ± 0.03 | −0.39 ± 0.05 | 6 | 0.182 |

* P < 0.050 as determined by paired Student's t test.

Translocation of DVGLUT to the PM during exocytosis is a novel activity‐induced acid efflux mechanism

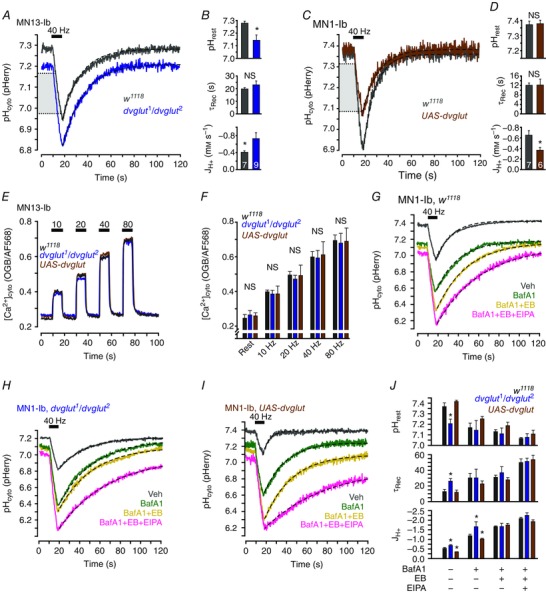

The hypothesis that DVGLUT can function as a acid efflux mechanism when SVs fuse to the PM was further tested by examining activity‐induced acid transients in DVGLUT‐deficient and DVGLUT over‐expressing larvae. dvglut1 is a hypomorphic allele of dvglut while dvglut2 is a deficient allele of dvglut. These alleles in trans lead to a 90% reduction in DVGLUT expression (Daniels et al. 2006). Comparison of activity‐induced acid transients in MN13‐Ib terminals of w1118 (n = 7) and dvglut1/dvglut2 (n = 9) larvae revealed that decreasing DVGLUT expression lowers resting pHcyto (7.14 ± 0.04 as compared to 7.28 ± 0.02 in controls; P = 0.013 by unpaired Student's t test) and reduces absolute activity‐induced JH+ (–0.78 ± 0.14 mM s–1 compared to –0.40 ± 0.04 mM s–1 in controls; P = 0.036 by unpaired Student's t test). τrec was unchanged between the groups (19.7 ± 1.1 to 23.0 ± 3.08 s; P = 0.271 by unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 6 A, B).

Figure 6. DVGLUT contributes to activity‐induced enhanced cytosolic acid efflux when deposited on the plasmamembrane during vesicular exocytosis.

A, averaged traces of activity‐induced cytosolic acid transients in MN13‐Ib terminals of w1118 (n = 7 larvae), and dvglut1/dvglut2 (n = 9) larvae. B, quantification of resting pHcyto, τrec and mean JH+ during stimulation in w1118 and dvglut1/dvglut2 larvae. C, averaged traces of activity‐induced pHcyto transients in MN1‐Ib terminals of w1118 (n = 6), and UAS‐dvglut (n = 6) larvae. D, quantification of mean JH+ during stimulation, τrec and resting pHcyto in w1118 and UAS‐dvglut larvae. Bars in B and D are mean ± SEM. * P < 0.050, unpaired Student's t test. E, representative traces of [Ca2+]cyto in MN1‐Ib terminals of w1118, dvglut1/dvglut2 and UAS‐dvglut larvae in response to repetitive stimulation with 8 s trains of action potentials at 10, 20, 40 and 80 Hz. F, quantification of peak [Ca2+]cyto of w1118, dvglut1/dvglut2 and UAS‐dvglut larvae at rest and each indicated stimulation frequency (same data as in E, see Table 2 for values). n = 4 larvae of each genotype. Mean ± SEM. NS, not significant, P > 0.050, one‐way ANOVA conducted between genotypes at each stimulation frequency and at rest. G–I, averaged traces of activity‐induced pHcyto transients in MN1‐Ib terminals of w1118, dvglut1/dvglut2 and UAS‐dvglut larvae after 20 min incubation and depletion stimulation (30 Hz for 6 min) in vehicle, 1 μM BafA1, 1 μM BafA1 + 10 μM EB, or 1 μM BafA1 + 10 μM EB + 50 μM EIPA as indicated. n = 6 larvae in all groups. J, quantification of resting pHcyto, τrec and mean JH+ during stimulation in w1118, dvglut1/dvglut2 and UAS‐dvglut larvae exposed to one of four drug combinations as indicated. Mean ± SEM. See Table 3 for values. * P < 0.050, one‐way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc test between genotypes within each drug combination. Stimulation (black bar) was 40 Hz for 8 s in A, C and G–I. Dashed lines in A, C and G–I are single exponential curves. Light grey boxes in A and C indicate the overlapping pHcyto range within which JH+ during stimulation was calculated in B and D. JH+ represented in J was calculated over the full stimulation duration in experiments shown in G–I.

Converse effects on activity‐induced acid transients were observed in larvae overexpressing DVGLUT using the UAS‐dvglut transgene (n = 6; n = 7 for w1118 controls) (Fig. 6 C). These experiments were conducted in M1‐Ib driving transgenes with the RRa‐GAL4 driver as pan‐neuronal overexpression led to neurodegeneration (Daniels et al. 2011). Resting pHcyto and τrec were unchanged by DVGLUT overexpression (7.37 ± 0.02 to 7.37 ± 0.02 and 12.0 ± 0.97 s to 12.0 ± 2.49 s; P = 0.999 and 0.997 by unpaired Student's t test). Activity‐induced acid efflux was increased in UAS‐dvglut larvae as absolute JH+ decreased from –0.64 ± 0.10 to –0.38 ± 0.05 mM s–1 (P = 0.047 by unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 6 D). These data suggest that overexpression of DVGLUT in MN terminals can limit net acid influx by enhancing activity‐induced acid efflux.

Over‐ and reduced expression of DVGLUT only caused statistically resolvable changes in JH+ and alterations in JH+ alone might be solely attributable to variation in [Ca2+]cyto levels during stimulation (Fig. 2 G). This is a plausible outcome of modulating DVGLUT expression as neurotransmission and [Ca2+]cyto are homeostatically regulated. To determine if changes in [Ca2+]cyto handling were responsible for the observed changes in JH+, [Ca2+]cyto levels during rest and increasing frequencies of stimulation were assessed in MN1‐Ib terminals of w1118, dvglut1/dvglut2 and UAS‐dvglut larvae (Fig. 6 E). Quantification of these data revealed no change in [Ca2+]cyto levels between genotypes and thus changes in JH+ are attributable to acid efflux through DVGLUT and not secondary changes in [Ca2+]cyto handling (Fig. 6 F, see Table 2 for values).

Table 2.

[Ca2+]cyto levels during stimulation and rest do not correlate with expression levels of DVGLUT in motorneuron terminals

| Genotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w1118 | dvglut1/dvglut2 | UAS‐dvglut | ||||||

| Condition | Units | Mean ± SEM | n | Mean ± SEM | n | Mean ± SEM | n | F 2,9 |

| OGB/AF568 fluorescence ratio | ||||||||

| Rest | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 4 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.196 | |

| 10 Hz | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 4 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 4 | 2.405 | |

| 20 Hz | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 4 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 4 | 0.111 | |

| 40 Hz | 0.61 ± 0.08 | 4 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 4 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 4 | 0.030 | |

| 80 Hz | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 4 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 4 | 0.69 ± 0.03 | 4 | 0.018 | |

P > 0.050 as determined by one‐way ANOVA for all comparisons.

The machinery necessary to load glutamate into SVs relies on multiple ionic gradients maintained by several protein complexes, and thus it is possible that differences in acid efflux between larvae with different DVGLUT expression levels are due to modulation in expression of other H+ transporters which are obligatorily co‐translocated with DVGLUT rather that H+ transport by DVGLUT itself. The specific in situ contribution of DVGLUT to activity‐induced acid transients was characterized through a combined pharmacological/genetic approach. Activity‐induced acid transients in MN1‐Ib terminals of w1118, dvglut1/dvglut2 and UAS‐dvglut larvae were analysed following incubation in one of four conditions (Fig. 6 G–I): vehicle, 1 μM BafA1, 1 μM BafA1 and 10 μM EB, or 1 μM BafA1 and 10 μM EB and 50 μM EIPA. The drug effects were similar to those seen in application of the separate drugs and were additive. However, comparisons of resting pHcyto, JH+ and τrec demonstrated differences between genotypes when treated with vehicle and BafA1 that were abolished when EB was added to the drug cocktail (Fig. 6 J, see Table 3 for values and analysis). These results suggest the differences in acid efflux between genotypes are attributable to an EB‐sensitive mechanism. Furthermore, this mechanism is likely to be acid efflux mediated by DVGLUT rather than a co‐translocated H+ transporter.

Table 3.

Modulation of activity‐induced pHcyto acid transients in motorneuron terminals by drugs which target acid transporters varies between larvae with different DVGLUT expression levels

| Genotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w1118 | dvglut1/dvglut2 | UAS‐dvglut | ||||||

| Treatment | Value | Mean ± SEM | n | Mean ± SEM | n | Mean ± SEM | n | F DF |

| pHrest | ||||||||

| Veh. | 7.37 ± 0.04 | 8 | 7.21 ± 0.04 | 6 | 7.42 ± 0.01 | 7 | 10.311(2,18) * | |

| BafA1 | 7.17 ± 0.04 | 6 | 7.14 ± 0.10 | 6 | 7.25 ± 0.02 | 6 | 0.892(2,15) | |

| BafA1+EB | 7.13 ± 0.02 | 6 | 7.11 ± 0.06 | 6 | 7.19 ± 0.03 | 9 | 1.193(2,18) | |

| BafA1+EB+EIPA | 7.07 ± 0.01 | 6 | 7.08 ± 0.03 | 7 | 7.11 ± 0.04 | 6 | 0.496(2,15) | |

| τrec (s) | ||||||||

| Veh. | 30.3 ± 5.81 | 8 | 30.4 ± 9.11 | 6 | 22.7 ± 3.74 | 7 | 6.449(2,18) * | |

| BafA1 | 31.1 ± 2.75 | 6 | 36.9 ± 7.73 | 6 | 27.8 ± 2.90 | 6 | 0.342(2,15) | |

| BafA1+EB | 31.1 ± 2.75 | 6 | 36.9 ± 7.73 | 6 | 27.8 ± 2.90 | 9 | 1.027(2,18) | |

| BafA1+EB+EIPA | 50.0 ± 4.61 | 6 | 51.4 ± 4.17 | 7 | 53.7 ± 5.62 | 6 | 0.143(2,15) | |

| JH+ (mm s–1) | ||||||||

| Veh. | –0.53 ± 0.05 | 8 | –0.68 ± 0.05 | 6 | –0.35 ± 0.01 | 7 | 14.833(2,18) * | |

| BafA1 | –1.19 ± 0.07 | 6 | –1.66 ± 0.26 | 6 | –1.01 ± 0.05 | 6 | 4.480(2,15) * | |

| BafA1+EB | –1.68 ± 0.04 | 6 | –1.68 ± 0.17 | 6 | –1.76 ± 0.08 | 9 | 0.218(2,18) | |

| BafA1+EB+EIPA | –2.09 ± 0.07 | 6 | –2.25 ± 0.13 | 7 | –1.92 ± 0.10 | 6 | 2.259(2,15) | |

* P < 0.050 as determined by one‐way ANOVA.

DVGLUT displays intrinsic Na+/H+‐exchange activity when expressed in Xenopus oocytes

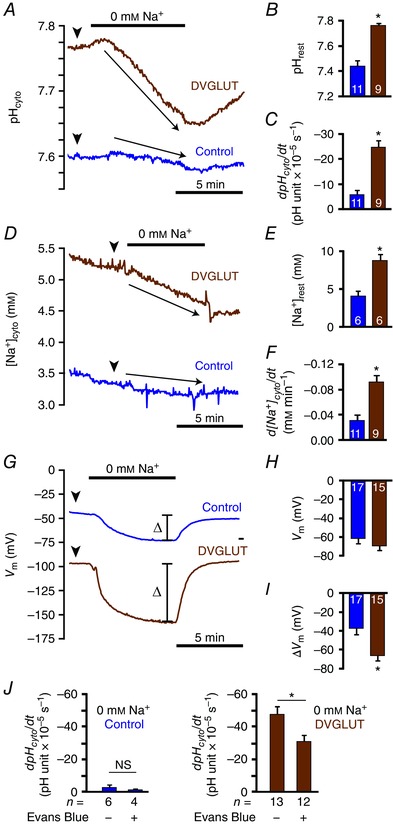

Although the data above provide strong evidence of H+ transport by DVGLUT at the PM in situ, the mechanism by which this could be achieved has never been explicitly demonstrated. Ion transport via DVGLUT has not been previously characterized, but mammalian VGLUT1 possesses binding sites for Cl−, cations, H+ and glutamate, which suggests some VGLUTs may be capable of intrinsic cation/H+ exchange (Preobraschenski et al. 2014). Na+/H+ exchange is the most likely DVGLUT‐mediated H+ transport mechanism to be present in a Drosophila MN terminal as the neuronal PM possesses a strong ΔμNa+. Na+/H+‐exchange activity of DVGLUT was directly assessed by analysing Xenopus oocytes expressing DVGLUT (DVGLUT oocytes) using ion‐selective microelectrodes. Resting pHcyto of DVGLUT oocytes (n = 9) was significantly higher than that of the water‐injected control oocytes (n = 11; 7.76 ± 0.02 compared to 7.44 ± 0.04 in controls; P < 0.001 by unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 7 A, B), resting [Na+]cyto of DVGLUT oocytes (n = 6) was 2.2‐fold higher than that of control oocytes (n = 6; P = 0.002 by unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 7 D, E), and resting membrane potential (V m) of DVGLUT oocytes (n = 15) was no different than that of control oocytes (n = 17; P = 0.367 by unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 7 G, H). When DVGLUT oocytes (n = 9) were incubated in Na+‐free solution, significant influx of H+ was observed as a significant decrease in pHcyto [−24.5 ± 2.6 ΔpH units × 105 s−1 compared to –5.8 ± 1.6 in controls (n = 11); P < 0.001 by unpaired Student's t test] (Fig. 7 A, C). In addition, Na+ efflux of DVGLUT oocytes (n = 9) was observed as a significant decrease in [Na+]cyto when exposed to Na+‐free solution [−0.092 ± 0.009 mM min–1 compared to –0.031 ± 0.003 mM min–1 in controls (n = 11); P < 0.001 by unpaired Student's t test] (Fig. 7 D, F). DVGLUT oocytes (n = 15) also showed hyperpolarization to a greater extent than controls (n = 17) when exposed to Na+‐free solution (P = 0.002 by unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 7 G, I). In sum, these results indicate that DVGLUT acts as a Na+/H+‐exchanger when expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

Figure 7. DVGLUT displays Na+/H+‐exchange activity when expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

A, representative traces of pHcyto changes upon removal of Na+ in DVGLUT and control (water‐injected) oocytes. B, quantification of resting pHcyto (arrowheads in A) in DVGLUT (n = 9) and control (n = 11) oocytes. C, quantification of rate of pHcyto change (arrows in A) upon removal of Na+ in DVGLUT (n = 9) and control (n = 11) oocytes. D, representative traces of [Na+]cyto changes upon removal of Na+ in DVGLUT and control oocytes. E, quantification of resting [Na+]cyto (arrowheads in D) in DVGLUT (n = 6) and control (n = 6) oocytes. F, quantification of rate of [Na+]cyto change (arrows in D) upon removal of Na+ in DVGLUT (n = 9) and control (n = 11) oocytes. G, representative traces of V m changes following removal of Na+ in DVGLUT and control oocytes. H, quantification of resting V m (arrowheads in G) in DVGLUT (n = 15) and control (n = 17) oocytes. I, quantification of total change in V m (bars in G) upon removal of Na+ in DVGLUT (n = 15) and control (n = 17) oocytes. J, quantification of rate of pHcyto change upon removal of Na+ with and without incubation in 20 μm EB in DVGLUT (n = 12 treated, 13 untreated) and control (n = 4 treated, 6 untreated) oocytes. Mean ± SEM in B, C, E, F and H–J. * P < 0.050, unpaired Student's t test.

While the combined genetic/pharmacological approach presented in Fig. 6 strongly suggests DVGLUT contributes to activity‐induced acid efflux from presynaptic terminals it is possible such effects are exaggerated due to indirect effects of EB on glutamate and H+ handling. This possibility is concerning as EB‐mediated inhibition of glutamate transporters has been characterized with regard to glutamate transport but not the intrinsic Na+/H+ exchange implied by the data above. Inhibition of DVGLUT‐mediated Na+/H+ exchange by EB was explicitly assessed by comparing pHcyto changes observed upon Na+ removal in DVGLUT and control oocytes in the presence and absence of EB. The rate of pHcyto decrease upon Na+ removal was significantly diminished in DVGLUT oocytes treated with EB as compared to those treated with water (−34.3 ± 4.9 ΔpH units × 105 s−1 compared to –58.5 ± 5.7, n = 12 and 13, respectively; P = 0.004 by unpaired Student's t test). EB had no effect on the rate of pHcyto decrease in water‐injected oocytes (–0.3 ± 1.2 ΔpH units × 105 s−1 compared to –2.2 ± 1.4, n = 4 and 6, respectively; P = 0.368 by unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 7 J). These results indicate EB can inhibit DVGLUT‐mediated Na+/H+ exchange.

Discussion

This study examined the extent to which SV exocytosis shapes activity‐induced pHcyto transients in glutamatergic MN terminals through translocation of acid transporters to the PM. Cytosolic expression of the pseudo‐ratiometric fluorescent GEpHI pHerry permitted measurement of acid dynamics within individual MN terminals. While intrinsic acid extrusion from MN terminals accelerates when pHcyto falls (Fig. 2 A, B), acid extrusion following action potentials trains is much faster than predicted by activation of acid extruders by low pHcyto (Fig. 2 C–E). Activity‐induced acid extrusion partially offsets Ca2+‐dependent acidification during nerve activity and continues for seconds after nerve activity. Complementary genetic and pharmacological approaches revealed this activity‐induced acid efflux to be mediated by NHEs, the vATPase and Na+/H+ exchange through DVGLUT (Figs 5 and 6, and Table 3).

Previous work has shown depolarization produces significant acid loading in soma, axons and presynaptic terminals of many neuronal preparations (Brown & Meech, 1979; Endres et al. 1986; Schwiening & Willoughby, 2002; Rossano et al. 2013). While less common, there are several reports of depolarization‐induced acid efflux from neurons (Sanchez‐Armass et al. 1994; Zhan et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 2010). This report expands upon previous studies by characterizing mechanisms which shape rapid pHcyto transients in the context of established models of vesicular trafficking and [Ca2+]cyto dynamics. The latter is particularly important as [Ca2+]cyto is tightly regulated in presynaptic terminals and [Ca2+]cyto levels drive rapid acid influx and efflux mechanisms through direct Ca2+/H+ exchange via the PMCA and Ca2+‐dependent trafficking of vesicular H+ transporters, respectively.

Careful analysis of the relationship between pHcyto and [Ca2+]cyto was necessary to determine if alterations in activity‐induced pHcyto transients were directly due to changes in the location and activity of acid transporters or secondary to changes in [Ca2+]cyto levels. To this end the relationships between [Ca2+]cyto, JH+ and acid extrusion (τrec) as well as resting pHcyto and [Ca2+]e were quantified (Fig. 2 F–I). Many manipulations produced changes in resting pHcyto which cannot be explained by alterations in Ca2+ handling as resting pHcyto is independent of Ca2+ in Drosophila MN terminals (Fig. 2 I). Similarly, manipulations which altered τrec probably altered acid efflux directly as τrec is independent of Ca2+ loading during stimulation (Fig. 2 F, I). Interpreting manipulations which only altered JH+ during stimulation proved the most challenging as JH+ is proportional to Ca2+ loading during stimulation and thus changes in JH+ may represent changes in acid influx due to changes in Ca2+ handling or direct changes in acid efflux (Fig. 2 F, G). MN terminals with altered expression of DVGLUT only differed from their controls with respect to JH+ (Fig. 6 A–D). As there were no differences in bulk [Ca2+]cyto at rest or during stimulation between genotypes with different DVGLUT expression levels, differences in JH+ between genotypes are probably not due to changes in Ca2+ handling (Fig. 6 E, F), with the caveat that potential alterations in the Ca2+ and pH near‐membrane micro‐environments are not addressed in this analysis.

The data here indicate that activity‐induced acid efflux is mediated by multiple PM and vesicular acid extruders, namely NHEs, the vATPase and DVGLUT. The contribution of NHEs is unsurprising as NHE gene products are highly expressed in Drosophila larvae (Giannakou & Dow, 2001) and spontaneous vesicular fusion at the larval NMJ is sensitive to the NHE inhibitor amiloride (Caldwell et al. 2013). These results are corroborated here as application of the amiloride derivative EIPA decreased resting pHcyto and delayed acid extrusion in MN terminals (Fig. 5 A, B, Table 1). The contributions of the vATPase and DVGLUT to pHcyto transients are probably attributable to selective trafficking of these transporters to the PM during exocytosis as they are primarily vesicular proteins, although BafA1‐sensitive vATPases are constitutively present on the PM of many cells as well. Furthermore, genetic manipulations to impair vesicular endocytosis and exocytosis revealed that stopping vesicular fusion impaired acid extrusion while locking vesicular membrane at the PM enhanced acid clearance following both NH4 + withdrawal and activity‐induced acid loading (Figs 3 and 4). The conclusion that both the vATPase and DVGLUT are functional components of the recycling pool of vesicular proteins which shape activity‐induced pHcyto transients is further supported by the observation that application of both the glutamate transporter inhibitor EB and BafA1, an established vATPase inhibitor, decrease acid clearance following activity‐induced acid loading (Fig. 5 C–F, Table 1). These results agree with a previous report that trafficking of the vATPase to the PM can alkalinize the cytosol of mouse cholinergic MN terminals (Zhang et al. 2010).

The notion that the DVGLUT can function at the PM as an acid extruder requires careful consideration as exact transport mechanisms of VGLUTs are unclear and no previous studies have been conducted to elucidate the transport mechanisms of DVGLUT, although it is reasonable to assume its transport modalities are generally similar to those of mammalian VGLUT1 (Preobraschenski et al. 2014). Here, a combined pharmacological and genetic approach provided the most compelling evidence for acid efflux mediated by DVGLUT (Fig. 6). This conclusion is further supported by the observation that EB can inhibit DVGLUT‐mediated Na+/H+ exchange in oocytes (Fig. 7 J). Experiments in which EB has been used to inhibit VGLUTs have been historically interpreted by assuming a primary effect on glutamate transport, not H+ dynamics. If intrinsic Na+/H+ exchange is a shared property of mammalian VGLUTs it is possible that prior work with EB has erroneously ascribed changes in neurotransmitter loading to direct inhibition of glutamate transport rather than secondary effects of inhibited cation/H+ exchange.

The bioenergetics of vesicular glutamate transporters are undoubtedly vital to modulation of neurotransmitter release. Studies of mammalian VGLUTs in heterologous expression systems suggest that VGLUTs are primarily driven by ΔΨH+ of ΔμH+ across the vesicular membrane, which is established by the vATPase (Johnson et al. 1981; Maycox et al. 1988; Saroussi & Nelson, 2009). Maintenance of ΔΨH+ requires dissipation of ΔpH via H+ exchange with another cation to enable continuous proton pumping and glutamate transport (Goh et al. 2011). It is unclear if H+/cation exchange is due to co‐transport with another ion transporter, as has been described in insect midgut where co‐expression of vATPase and Na+‐coupled nutrient amino acid transporters form a functional NHE (Harvey et al. 2009), or is an intrinsic property VGLUTs, as has been described in mammalian VGLUT1 (Preobraschenski et al. 2014). The data presented here provide the first direct evidence that intrinsic EB‐sensitive Na+/H+ exchange is a property of DVGLUT (Fig. 7). Taken with the observation that the in situ effects of EB are only additive with those of BafA1 in the presence of significant DVGLUT expression (Fig. 6) it is very likely that Na+/H+ exchange via DVGLUT contributes to activity‐enhanced acid efflux across the PM of MN terminals. The electroneutrality of ion exchange by DVGLUT requires further investigation as changes in V m upon removal of Na+ from oocytes expressing DVGLUT is probably attributable to decrease in the PM Na+ gradient rather than electrogenic Na+/H+ exchange by DVGLUT (Fig. 7 D–I).

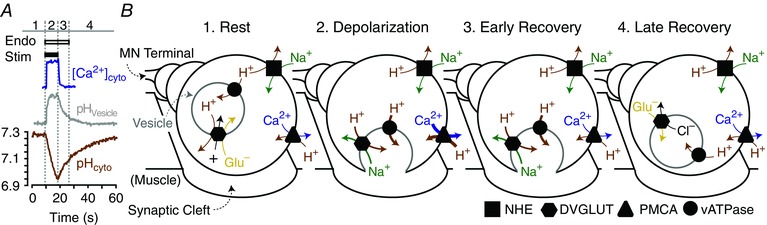

The following model of pHcyto regulation by DVGLUT reconciles the observation that DVGLUT is a mediator of activity‐induced acid extrusion with the available data from mammalian VGLUT ion transport mechanisms (Fig. 8). In quiescent nerve terminals NHEs mediate a standing acid efflux and DVGLUT is primarily on the vesicular membrane where it loads glutamate into the vesicular lumen via ΔΨH+ generated by the vATPase. The growing ΔpH across the vesicular membrane is dissipated by DVGLUT through cation/H+ exchange. Under these conditions K+/H+ exchange is most likely as K+ is much more abundant than Na+ in the cytosol and previous work has demonstrated functional K+/H+ exchange across organellar membranes in rat synaptosomes (Goh et al. 2011) and amphibian vestibular hair cells (Hill et al. 2006; see also Ohgaki et al. 2011 for a review). Upon exocytosis to the PM the directionality of DVGLUT reverses and acid efflux is mediated by Na+/H+ exchange driven by the strong ΔμNa+ at the PM. Upon cessation of neuronal activity, DVGLUT contributes to an early phase of accelerated acid efflux until it is retrieved from the PM by endocytosis. In recently endocytosed vesicles the elevated Cl− concentration of the vesicular lumen drives glutamate into the vesicle by a Cl− shunt mechanism (Schenck et al. 2009; Preobraschenski et al. 2014). As the vesicular ΔΨH+ generated by the vATPase is re‐established the cycle completes. The model presented above describes a mechanism by which acid efflux can scale to effectively clear the overall net acid load through enhanced trafficking of acid‐extruding proteins, including DVGLUT, to the PM, thus maintaining tight control of pHcyto in the face of large PMCA‐medicated acid loads during nerve activity.

Figure 8. Schematic of proposed model for activity‐driven acid influx and efflux mechanisms in Drosophila MN terminals.

A, schematic of changes in pHcyto, pHvesicle and [Ca2+]cyto in a MN terminal in response to a stimulation train of 40 Hz over 8 s. Distinct phases of activity based on time course of [Ca2+]cyto peak, vesicular endocytosis (derived from pHvesicle) and recovery of pHcyto after stimulation labelled 1–4. B, proposed ion transport mechanisms across the vesicular and plasmamembranes which contribute to acid influx and efflux from the MN terminal cytosol in each of the phases of neuronal activity described in A. Arrow thickness is proportional to relative amount of ion movement.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests, financial or otherwise.

Author contributions

AJR and GTM designed the experiments and contributed to the intellectual conception of the work. AJR, GTM and AK collected data. AJR, GTM, MFR and AK provided data interpretation and analysis. AJR drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for the all aspects of the accuracy and integrity of the work presented. All persons listed as authors qualified for authorship and all persons qualified as authors are listed as such.

Funding

This work was funded by NIH R21 NS083031 to GTM, NIH DK092408 and NIH EY017732 to MFR, and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25650114 to AK.

Linked articles This article is highlighted by a Perspective by Venkatachalam. To read this Perspective, visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1113/JP273469.

References

- Arosio D, Ricci F, Marchetti L, Gualdani R, Albertazzi L & Beltram F (2010). Simultaneous intracellular chloride and pH measurements using a GFP‐based sensor. Nat Methods 7, 516–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines RA, Robinson SG, Fujioka M, Jaynes JB & Bate M (1999). Postsynaptic expression of tetanus toxin light chain blocks synaptogenesis in Drosophila . Curr Biol 9, 1267–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcar VJ, Johnston GA & Twitchin B (1977). Stereospecificity of the inhibition of l‐glutamate and l‐aspartate high affinity uptake in rat brain slices by threo‐3‐hydroxyaspartate. J Neurochem 28, 1145–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron WF & De Weer P (1976). Intracellular pH transients in squid giant axons caused by CO2, NH3, and metabolic inhibitors. J Gen Physiol 67, 91–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH & Perrimon N (1993). Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HM & Meech RW (1979). Light induced changes of internal pH in a barnacle photoreceptor and the effect of internal pH on the receptor potential. J Physiol 297, 73–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell L, Harries P, Sydlik S & Schwiening CJ (2013). Presynaptic pH and vesicle fusion in Drosophila larvae neurones. Synapse 67, 729–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler M (1990). The regulation and modulation of pH in the nervous system. Prog Neurobiol 34, 401–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu TS, Peng Y, Cano A, Yanagisawa M & Alpern RJ (1996). Endothelin(B) receptor activates NHE‐3 by a Ca2+‐dependent pathway in OKP cells. J Clin Invest 97, 1454–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craymer L (1984). TM6B: Third Multiple Six, B structure. Dros Inf Serv 60, 234. [Google Scholar]

- Dason JS & Charlton MP (2014). A novel extraction protocol to probe the role of cholesterol in synaptic vesicle recycling. Methods Mol Biol 1174, 361–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC (2001). Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol 65, 1–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels RW, Collins CA, Chen K, Gelfand MV, Featherstone DE & DiAntonio A (2006). A single vesicular glutamate transporter is sufficient to fill a synaptic vesicle. Neuron 49, 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels RW, Collins CA, Gelfand MV, Dant J, Brooks ES, Krantz DE & DiAntonio A (2004). Increased expression of the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter leads to excess glutamate release and a compensatory decrease in quantal content. J Neurosci 24, 10466–10474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels RW, Miller BR & DiAntonio A (2011). Increased vesicular glutamate transporter expression causes excitotoxic neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis 41, 415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow JA (1999). The multifunctional Drosophila melanogaster V‐ATPase is encoded by a multigene family. J Bioenerg Biomembr 31, 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil RR, Das A, Base C & Mazock GH (2010). The Drosophila anion exchanger (DAE) lacks a detectable interaction with the spectrin cytoskeleton. J Negat Results Biomed 9, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres W, Ballanyi K, Serve G & Grafe P (1986). Excitatory amino acids and intracellular pH in motoneurons of the isolated frog spinal cord. Neurosci Lett 72, 54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Ueda A & Wu CF (2004). A modified minimal hemolymph‐like solution, HL3.1, for physiological recordings at the neuromuscular junctions of normal and mutant Drosophila larvae. J Neurogenet 18, 377–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka M, Lear BC, Landgraf M, Yusibova GL, Zhou J, Riley KM, Patel NH & Jaynes JB (2003). Even‐skipped, acting as a repressor, regulates axonal projections in Drosophila . Development 130, 5385–5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi M, Hernandez A, McGough IJ & Vincent JP (2014). Inhibitors of endocytosis prevent Wnt/Wingless signalling by reducing the level of basal β‐catenin/Armadillo. J Cell Sci 127, 4918–4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakou ME & Dow JA (2001). Characterization of the Drosophila melanogaster alkali‐metal/proton exchanger (NHE) gene family. J Exp Biol 204, 3703–3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh GY, Huang H, Ullman J, Borre L, Hnasko TS, Trussell LO & Edwards RH (2011). Presynaptic regulation of quantal size: K+/H+ exchange stimulates vesicular glutamate transport. Nat Neurosci 14, 1285–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DJ & Gillette R (1988). Regulation of cAMP‐stimulated ion current by intracellular pH, Ca2+, and calmodulin blockers. J Neurophysiol 59, 248–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]