Abstract

After spinal cord injury (SCI) muscle contractures develop in the plegic limbs of many patients. Physical therapists commonly use stretching as an approach to avoid contractures and to maintain the extensibility of soft tissues. We found previously that a daily stretching protocol has a negative effect on locomotor recovery in rats with mild thoracic SCI. The purpose of the current study was to determine the effects of stretching on locomotor function at acute and chronic time points after moderately severe contusive SCI. Female Sprague-Dawley rats with 25 g-cm T10 contusion injuries received our standard 24-min stretching protocol starting 4 days (acutely) or 10 weeks (chronically) post-injury (5 days/week for 5 or 4 weeks, respectively). Locomotor function was assessed using the BBB (Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan) Open Field Locomotor Scale, video-based kinematics, and gait analysis. Locomotor deficits were evident in the acute animals after only 5 days of stretching and increasing the perceived intensity of stretching at week 4 resulted in greater impairment. Stretching initiated chronically resulted in dramatic decrements in locomotor function because most animals had BBB scores of 0–3 for weeks 2, 3, and 4 of stretching. Locomotor function recovered to control levels for both groups within 2 weeks once daily stretching ceased. Histological analysis revealed no apparent signs of overt and persistent damage to muscles undergoing stretching. The current study extends our observations of the stretching phenomenon to a more clinically relevant moderately severe SCI animal model. The results are in agreement with our previous findings and further demonstrate that spinal cord locomotor circuitry is especially vulnerable to the negative effects of stretching at chronic time points. While the clinical relevance of this phenomenon remains unknown, we speculate that stretching may contribute to the lack of locomotor recovery in some patients.

Keywords: : locomotor function, rehabilitation, spinal cord injury

Introduction

Severe but incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI) results in partial paralysis below the level of injury because of the loss of descending inputs onto voluntary motor and the more automated locomotor circuitry of the spinal cord. Partial paralysis, in turn, results in prolonged periods of immobility accompanied by significant alterations in the musculoskeletal components.1 Over time, the spinal cord circuitry below the level of injury undergoes a number of adaptations that lead to an increase in alpha motoneuron excitability.2,3 This increase can be associated with improvements in locomotor function.2,4 The system, however, lacks appropriate modulation by inhibitory circuitry because of impaired control from supraspinal centers5–7 and local maladaptive plasticity.8 These changes combine to result in exaggerated motor output (hypertonia and spasticity) in response to muscle stretch and/or other sensory input.9 As a result, some level of spacicity develops in approximately 78% of patients with chronic SCI.10

Although spasticity has potential benefits for some patients, indirectly contributing to their ability to stand or perform daily tasks such as transfers, it also presents a multitude of unwanted consequences that presumably contribute to more than half of the patient population with spasticity reporting it as a major obstacle to resumption of activities of daily living.11 Unmanaged spasticity, where muscles remain in shortened positions for prolonged periods can lead to the development of joint and muscle contractures that manifest as dramatically decreased range of motion (ROM)12 about affected joints.

Preservation of a functional ROM is not only important for timely initiation of rehabilitation,13 but it also can significantly improve independence in some patients with SCI. For example, an elbow contracture in patients with cervical level 6 injury rendered them unable to perform transfers and maintain bed mobility, functionally making them similar to patients with cervical level 5 injury.

Stretching remains the cornerstone for the treatment by physical therapists (PTs) of both spasticity and muscle contractures11,14,15; it is encouraged even in the absence of contractures to maintain soft tissue extensibility, because it is believed that preventing contractures is easier than treating them.16 Stretching provides a potent mechanical stimulus for the induction of protein synthesis17 and has been shown to result in serial addition of sarcomeres within muscle fibers,18 which can potentially prevent atrophy19 and decreases in muscle length. These observations suggest that muscle stretch should be an effective method for achieving desirable changes in muscle length or preventing undesirable changes in soft tissues; thus the rationale to include stretching therapy in the rehabilitation program for patients with SCI appears sound. Evidence that most commonly used stretching techniques actually improve symptoms of spasticity, ROM and/or prevent contracture formation in subjects with SCI is mixed at best, however.5

Previously, we found that wheelchair hindlimb immobilization in rats with mild-moderate spinal cord injuries resulted in the loss of locomotor function and, in addition, contractures developed in some animals, grossly similar to human patients.20 Thus, we invited PTs who work with human patients with SCI to guide us in the development of a clinically relevant stretching protocol for the treatment and prevention of contractures in hindlimb-immobilized animals as part of their daily care. The protocol was standardized for stretching muscles around the major hindlimb joints: ankle flexors/extensors, knee flexors/extensors, hip flexors/extensors, and hip adductors/abductors. Surprisingly, when the same stretching protocol was applied to control (nonimmobilized) injured rats, we found that it caused a decrease in their locomotor function.20

The goal of the current study was to extend these observations, using the same stretching protocol, to a more clinically relevant moderately severe spinal cord contusion model and to examine the effects of stretching at both acute and chronic time points. Based on our previous findings, we hypothesized that stretching would have detrimental effects on locomotor function in rats with spinal cord injuries at both acute and chronic time points.

Methods

SCI and study design

Twenty-two adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (190–230 g) were used in the study. All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. On arrival, animals underwent a weeklong acclimatization protocol that involved daily gentling and introduction to the experimental apparatus used for kinematic and behavioral assessments. Figure 1 shows a timeline for the entire experiment, including collection of the primary outcome measures. Rats received a T9 laminectomy followed by a T10 moderately severe spinal cord contusion (25 g/cm, NYU Impactor) as described previously.21

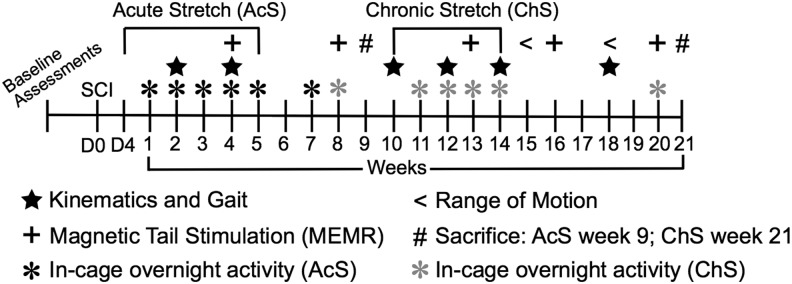

FIG. 1.

Timeline for the primary experimental procedures including functional assessments. SCI, spinal cord injury.

Animals were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups after the first behavioral locomotor assessment on day 4 post-injury: Acute Stretch (AcS, n = 10), Chronic Stretch (ChS, n = 9), or injury control for muscle histology (n = 3). The stretching protocol was implemented as described previously22 for the AcS group starting at 4 days post-injury and continuing for 5 weeks and for the ChS group starting at 10 weeks post-injury and continuing for 4 weeks. Stretching in the ChS group was stopped after 4 weeks because of the development of severe contractures in some of those animals and the inability of our PTs to achieve full end ROM during stretching.

Briefly, the stretching protocol consisted of two 12-min sessions of six static stretches (each held for 1 min at the end ROM) performed bilaterally of major hindlimb muscle groups: ankle flexors and extensors, quadriceps, hamstrings, and hip abductors/adductors (each muscle group received 2 min of stretch per day). There were seven PTs who participated in stretching sessions. Animals were rotated among the PTs such that no animal was stretched twice by the same therapist in any given week. PTs were trained on proper animal handling and hindlimb positioning for each stretch in a pilot study that is not reported. We did not measure the forces applied during stretching; thus, PTs were instructed to closely monitor the limb position and to achieve normal end ROM for each stretch. Stretching was performed 5 days a week (Monday–Friday). After 5 weeks of stretching, the AcS group survived for an additional 13 weeks and the ChS group for 7 weeks.

Locomotor functional assessments

Overground stepping was assessed using the Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan (BBB) Open Field Locomotor Scale23 as described previously. BBB assessments were performed three times per week: Monday am (pre-stretch), Monday pm (>1 h post-stretch), and Friday pm (>1 h post-stretch) during the weeks of stretching and once weekly (Monday am) when stretching ended. During the first 5 weeks, the ChS group served as a behavioral control for the AcS group. The BBB scores of the ChS group plateaued at 4 weeks post-injury, and they served as their own controls.

In addition, hindlimb kinematics and gait were assessed using digital video (sagittal and ventral views) acquired while the animals stepped in 2″ (5 cm) of water sufficient to supply approximately 60% body weight support, as described previously.24 We used a three-segment, two-angle model of the hindlimbs for kinematic analysis with the hip-ankle-toe (HAT) representing ankle and knee excursions and the iliac crest-hip-ankle (IHA) representing hip and knee excursions.

Gait analysis was derived from ventral view videos that allowed accurate identification of paw placement and timing, and each paw placement was determined to be plantar (paw and toes appropriately placed with dorsal surfaces up) or dorsal (with one or more toes curled and/or the paw itself oriented such that dorsal surface was observable in the ventral view). Three indices of gait were determined: the central pattern index (CPI), calculated as the number of correctly patterned plantar and dorsal steps over the total number of steps, the regularity index (RI), calculated as the number of correctly patterned plantar steps over the total number of steps (dorsal and plantar), and the plantar stepping index (PSI), calculated as the number of hindlimb plantar steps over the total number of forelimb steps. Kinematic and gait analyses were performed every other week using MaxTraq & MaxMate software (Innovision Systems Inc., Columbiaville, MI) and custom designed Excel macros.21,22

Nocturnal in-cage activity recordings

Overnight in-cage activity was measured once a week (Thursday) during the weeks of stretching using overhead cameras (Basler, acA645-100 gm) and infrared lights. A 2-cm tracking dot was drawn with a Sharpie pen on the shaved lower back of each animal. The recordings were made using custom software that acquired high-resolution video at 4 Hz for 1 min of every 10 for 12 h. The video recordings were analyzed using MaxTraq software and the distance travelled determined using a custom-designed Excel based add-in program. Discreet movements of the tracking dot that were less than 2.0 cm were not counted, thus removing much of the movement associated with grooming and sleeping.

Magnetically evoked potentials from tail stimulation

Previously, it was established that stretching affects both the mechanical properties of muscles and motoneuron excitability25; 30 sessions of stretching resulted in a temporary reduction in H-reflex amplitude.26 We thus wanted to determine whether our stretching protocol similarly affects the excitability of the gastrocnemius (GM) motoneuron pool after SCI. Unanaesthetized animals were restrained on a pine board using a cloth stockinette as described previously.27 Afferents in the base of the tail were stimulated using a 25-mm figure-8 magnetic coil attached to a MagStim 200 (MagStim Ltd., Whitland, U.K.); stimuli were delivered at 80% of maximum intensity, sufficient to induce a plateau response but avoid direct muscle/motor axon activation.28 GM muscle responses (EMGs) were recorded bilaterally using 26-gauge needle electrodes.22,27 EMGs were analyzed for onset latency and peak-to-peak amplitude. The assessments were performed every 4 weeks. During the weeks of stretching, the tail stimulation was performed at least 1 h after the last stretching session for each animal.

Histological procedures

Animals were overdosed with a ketamine (50 mg/kg)/xylazine (0.024 mg/kg)/acepromazine (0.005 mg/kg) cocktail and transcardially perfused with phosphate buffer, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA).29 The spinal cord and hindlimb muscles (biceps femoris [BF], GM, and tibialis anterior [TA]) were dissected out, post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight, and cryprotected with 30% sucrose. The fixed spinal cords were carefully examined to confirm the injury level (T10) and 1-cm long pieces containing the injury epicenter were prepared and placed in tissue freezing medium. Transverse sections were cut at 30 μm and stained for spared white matter using eriochrome cyanine (EC).27 Photomicrographs were acquired at 4X magnification. Cross-sectional area of compact, darkly stained white matter was traced and measured using ImageJ software (NIH) as described previously.16

Muscles were divided in two at the midbelly, placed in tissue freezing medium, and transverse sections were cut at 18 μm. Sections were stained with Masson Trichrome for collagen as a marker of tissue fibrosis and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for identification of centralized nuclei as a marker of regenerating muscle fibers. For collagen quantification, two 10X images were taken from midbelly sections in specified areas oriented to consistent vascular landmarks (branches of the posterior tibial artery) in the posteromedial portion of the TA muscle (or to fascia separating the two heads of the GM and BF muscles that were present in all animals. Area (mm2) of collagen was measured using ImageJ. Manual tracing of 150 random midbelly muscle fibers was performed, per muscle, and cross-sectional area (CSA) was determined using ImageJ. It was previously established that a sample size of 150 fibers is sufficient to accurately estimate the mean muscle fiber CSA.30 Muscle fibers with centralized nuclei were counted from three 40X images and normalized to the total number of muscle fibers analyzed for each animal (reported as a percentage). Histological analysis was performed by a person blinded to the experimental groups.

ROM assessment

After 4 weeks of stretching therapy, it was noted that ChS animals had reduced ROM about the hip and knee joints. To confirm this observation, we measured passive ROM around those joints at week 15 post-injury. The animals were restrained as for stretching, and each hindlimb was moved into hip/knee extension/knee flexion until passive resistance was felt. A goniometer was used to measure the joint angles as described previously.12 ROM assessment was repeated at week 18 post-SCI when locomotor function had recovered to pre-stretch levels.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as group means ± standard deviation. Mixed model repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA), fixed and random effects, followed by Bonferroni post hoc t tests were performed on all outcome measures except gait indices. Nonparametric one-sample t tests were performed to analyze the CPI, PSI, and RI in chronic stretch animals and PSI and RI of the acute stretch group. A binomial proportions nonparametric test was performed to analyze CPI in the acute stretch group. Differences between groups and/or time points were considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Open field locomotor function assessments

Stretching caused a drop in the BBB scores of both the AcS and ChS groups. Overall, RM ANOVA showed significant difference between groups (F = 27.9, df = 1,12, p < 0.001) and within group time points (F = 37.5, df = 20,12, p < 0.001). During the first 2 weeks of stretching, the hindlimbs of the AcS group were flaccid, and end ROM was achieved easily during the stretching sessions, with a low perceived force being applied by the PTs. Muscle tone returned, however, by week 3, and the PTs noted that the perceived force needed to achieve the desired stretching positions had increased. Figure 2A shows that the BBB scores were apparently more influenced by stretching at weeks 4 and 5, when additional perceived force was used, and a significant difference was observed at week 5 (p < 0.005). Two weeks after the stretching protocol ended the BBB scores of the AcS group recovered to the level of the unstretched ChS animals, albeit with high variability.

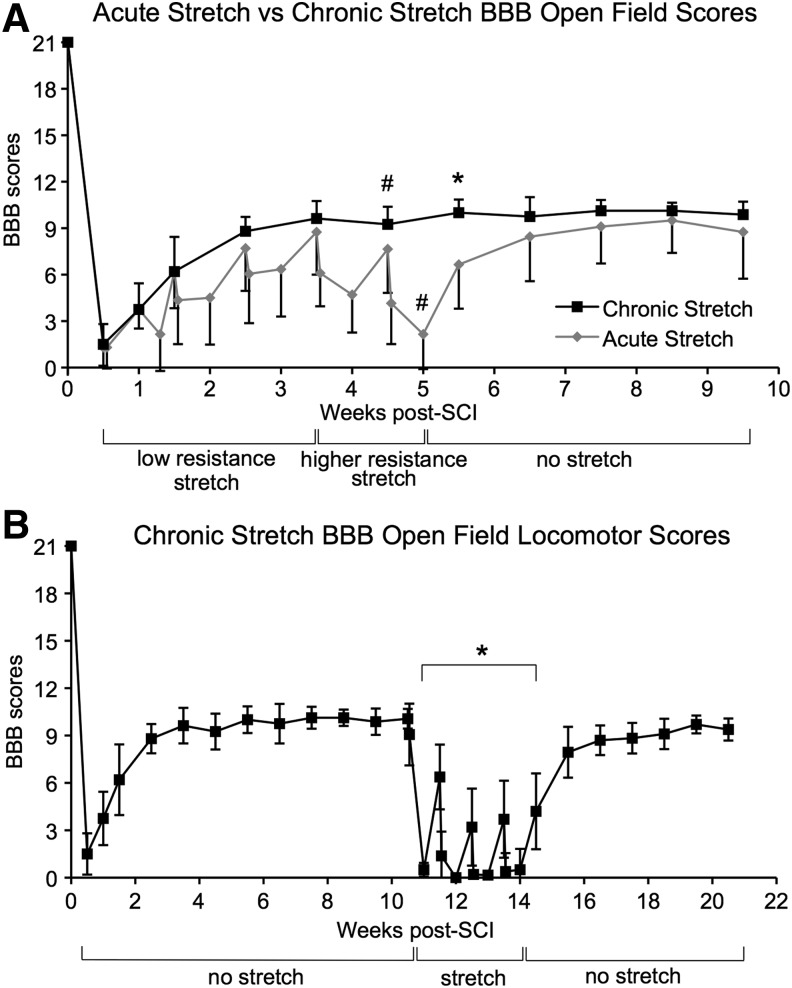

FIG. 2.

Acute and chronic Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan (BBB) Open Field Locomotor Scores. (A) BBB scores are shown for the acute and chronic (ChS) stretch groups over the first 10 weeks post-injury. Drops in BBB scores were modest and not significant during the first 4 weeks but became significant at 5 weeks after higher perceived forces were applied starting at week 4. #Indicates significant differences between Monday morning and Friday afternoon BBB scores. *Indicates significant differences in BBB scores for stretched and unstretched groups. (B) BBB scores of the ChS group dropped dramatically after only 1 week of stretching. *Indicates significant differences between pre-stretch (week 10 Monday morning) and stretch BBB scores. SCI, spinal cord injury.

Locomotor function of the ChS group reached a plateau at post-injury week 4 and remained consistent for the next 6 weeks until the start of stretching at 10 weeks post-SCI (Fig. 2B). After only 1 week of stretching, BBB scores of the ChS group dropped to an average of 0.5 (p < 0.005); most animals had only slight movement of one joint on one side. By week 13, all nine animals had BBB scores of 0. The vulnerability of locomotor function to stretching at chronic time points was also revealed by the fact that one stretching session (Monday am) was enough to undermine any recovery that took place over the weekend when the animals were not stretched. Within 2 weeks of the last stretching session, the BBB scores for the ChS group recovered sufficiently to be not different from pre-stretch levels.

Kinematic and gait analysis of the locomotor function

Kinematic (HAT and IHA excursions) and gait analysis (CPI, PSI, RI) of the AcS animals are summarized in Figure 3A and C. RM ANOVA showed significant time point differences in AcS HAT (F = 42.7, df = 2,27, p < 0.001) and IHA excursions (F = 137.4, df = 2,27, p < 0.001). Specifically, HAT and IHA “joint” excursions were significantly lower at both week 4 and 8 compared with pre-SCI baseline (p < 0.05). In addition, HAT and IHA excursions were significantly lower at week 4 (during stretching therapy) compared with week 8, 3 weeks after the last stretching session (p < 0.05). At week 4, only 2 of 10 AcS animals achieved some dorsal stepping in shallow water and thus had a measureable CPI above 0; the remaining 8 did not step, and therefore had PSI and RI indices of 0. By week 8, AcS rats achieved significant recovery revealed by the PSI (p < 0.05) and CPI (p < 0.001).

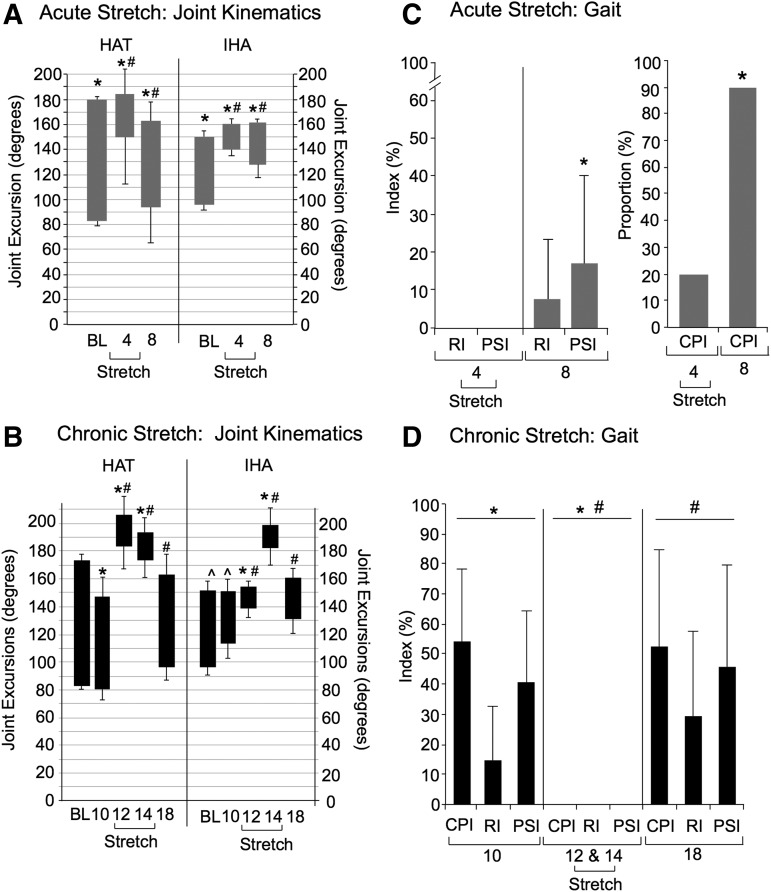

FIG. 3.

Kinematic and gait analysis of shallow water walking (SWW). Distal (hip-ankle-toe, HAT) and proximal (iliac crest-hip-ankle, IHA) joint excursions are indicated by the bars: top and bottom of the bar represents the mean peak extension and flexion, respectively, of the joint angles ± standard deviation, and thus bar length represents the mean angular excursion or range of motion (ROM). (A) Acute Stretch (AcS): Significant differences are indicated by (*) for HAT and IHA joint excursions of AcS animals compared with the Chronic Stretch (ChS) group. Significant differences are indicated by (#) for IHA and HAT excursions of AcS animals at week 4 (during stretching therapy) compared with week 8 (3 weeks after the last stretching session). (B) ChS: Significant differences indicated by (*, #) for ChS animals when comparing weeks 10 or 18 with weeks 12 and 14. In addition, IHA excursions remained significantly lower at week 10 compared with baseline (^). (C) AcS: Significant differences (*) were seen when comparing central pattern index (CPI), plantar stepping index (PSI), and regularity index (RI) for week 4 and week 8. (D) Significant differences indicated by (*, #) for ChS animals when comparing weeks 10 or 18 with weeks 12 and 14.

Kinematics and gait analyses of the ChS group are shown in Figure 3, B and D. Overall, RM ANOVA showed significant time point differences in ChS HAT excursions (F = 275.9, df = 4,40, p < 0.001) and ChS IHA excursions (F = 376.1, df = 4,40, p < 0.001). At week 10 post-SCI, before stretching, HAT excursions had recovered sufficiently to not differ significantly from baseline (pre-injury), whereas IHA excursions were still significantly lower (p < 0.05). At weeks 12 and 14, during the stretching therapy, ChS animals dragged their hindlimbs resulting in very low angular excursions likely reflecting only passive movements of the ankle as the animal moved in shallow water. Figure 3 shows the significant differences (p ≤ 0.005) between pre-stretch IHA and HAT excursions (week 10), stretch (12 and 14) and week 18 (4 weeks after the last stretching session) when ChS animals regained locomotor function to a pre-stretch level.

By week 10 (before the beginning of stretching), CPI and PSI for the ChS group recovered to about 50% of normal, whereas RI remained poor, indicating that both the forelimbs and hindlimbs were achieving plantar stepping, but the two girdles were decoupled (poor or no hindlimb/forelimb coordination). During the weeks of stretching (weeks 12 and 14) RI, PSI, and CPI were all equal to zero, indicating a complete lack of stepping, which was significantly different (p < 0.05) from pre-stretch (week 10) values. Four weeks after the last stretching session (week 18), ChS animals regained the ability to step, indicated by the return of RI, PSI, and CPI to pre-stretch levels.

Nocturnal in-cage activity

In-cage, overnight activity was monitored, and the distances traveled were estimated using a 1 in 10 min sampling rate (Fig. 4). Even though mixed model RM ANOVA analysis of the AcS overnight distance traveled showed significant differences across time points (F = 4.9, df = 6,45, p < 0.001), post hoc t tests did not (Fig. 4A). Post-injury distances averaged approximately 150 m per animal per night by 4 weeks post-injury. Thus, stretching did not have an apparent effect on the in- cage activity of this group.

FIG. 4.

Nocturnal in-cage activity. (A) Acute Stretch: There were no statistically significant differences in distance traveled in the acute animals at any time points. (B) Chronic Stretch (ChS): Significant differences in overnight activity of ChS animals are indicated by (#, *) for ChS animals when comparing weeks 8 or 20 with weeks 11–14.

RM ANOVA showed significant differences in distance traveled of the ChS animals (F = 7.8, df = 7,48, p = 0.001). ChS animals averaged 149.3 m/night at week 8 (before stretching intervention) and 67.7 at week 13 (during the third week of stretching), which was significantly lower than week 8 (p < 0.05), while at week 14, the ChS group averaged 71.7 m/night (approaching significance, p = 0.061) (Fig. 4B). Further, overnight activity of the ChS animals was significantly lower (p < 0.05) at weeks 12, 13, and 14 (3 of the 4 weeks of stretching) compared with week 20, 4 weeks after the last stretching session. They recovered to 134.7 m/night by week 20, which was not different from pre-stretching (week 8) levels.

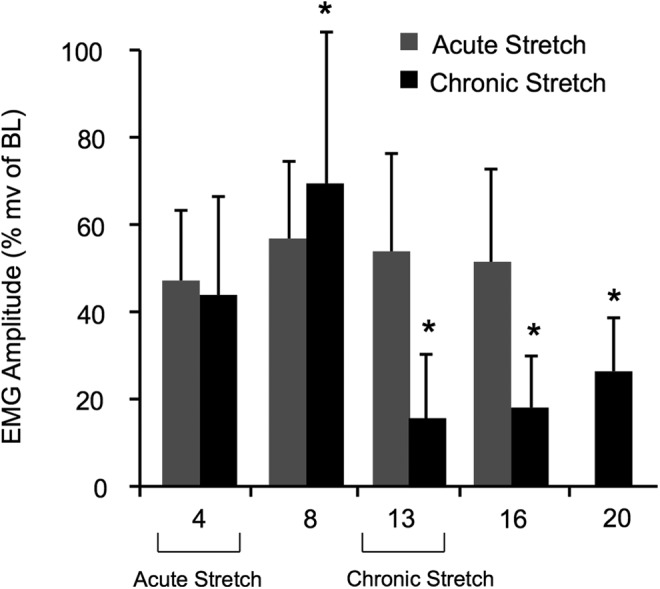

Magnetically Evoked Muscle Response (MEMR):

Responses of the GM muscle to magnetic stimulation of the base of the tail (MEMRs) were assessed every 4th week of the experiment. These short-latency (5–6 msec), presumed mono- or di-synaptic responses, reflect excitability of the GM motoneurons and any changes in the primary afferents and muscles themselves that could influence the EMG signal. Figure 5 shows MEMR data (post-SCI time points normalized to baseline). RM ANOVA showed significant group (F = 10.8, df = 1,3, p < 0.005) and time point (F = 5.16, df = 4,3, p < 0.005) differences in normalized MEMR.

FIG. 5.

Amplitude of magnetically evoked muscle responses (MEMRs). Significant differences are indicated by (*, #) for Acute Stretch (AcS) and Chronic Stretch (ChS) animals when comparing normalized MEMRs at weeks 13, 16, or 20 to weeks 4 or 8. There was no difference in MEMRs when comparing AcS and ChS animals at week 4. EMG, gastrocnemius muscle responses; BL, baseline.

SCI resulted in a significant decrease in EMG amplitude for both acute (AcS) and chronic (ChS) groups (by about 50%). Stretching had no additional effect on MEMR in the AcS group, because the amplitude of the EMG responses did not differ significantly from the unstretched group (ChS) at week 4. The normalized response amplitude of the ChS animals dropped significantly at week 13 (measured during the 4th week of stretching), however, a significant decrease from the week 8 (pre-stretch) values. Responses remained significantly decreased at weeks 16 and 20 (2 and 5 weeks, respectively, after the last stretching session) even though BBB scores returned to control levels. The onset latency remained unchanged (5–6 msec) throughout in both groups (data not shown).

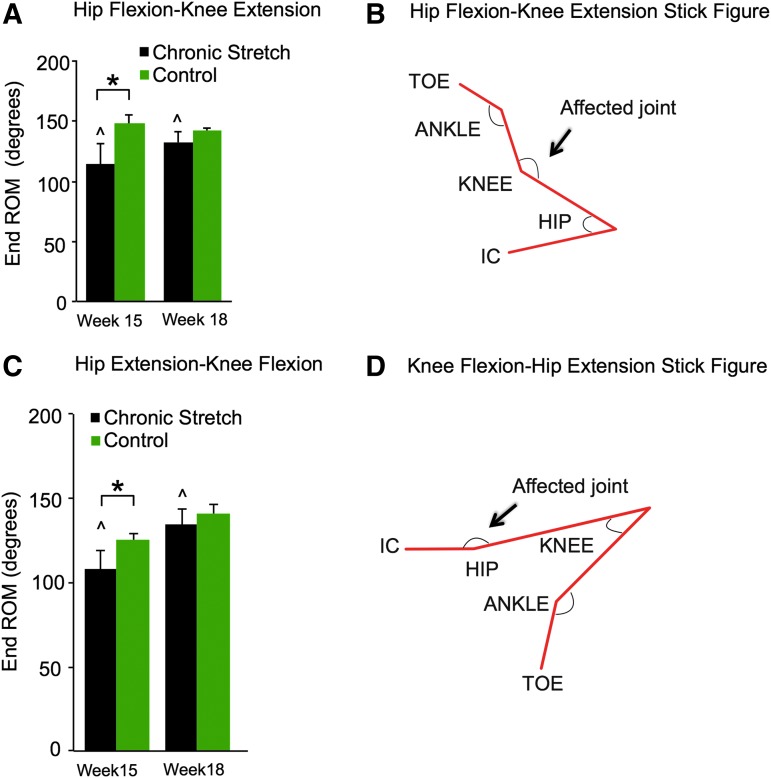

ROM

Significantly reduced locomotor function in the ChS at the end of the 4-week stretching protocol resulted in the development of contractures around the knee and hip joints. A reduced ROM around those joints was confirmed using a goniometer. RM ANOVA showed significant group differences in the knee (F = 14.34, df = 1,1, p < 0.005) and hip (F = 7.5, df = 1,1, p < 0.05) ROM values as well as significant time point difference in hip ROM (F = 21.3, df = 1,1, p < 0.001). At week 15, the ROM around the knee (Fig. 6A) and hip (Fig. 6B) joints of the ChS animals were significantly lower compared with control animals (p < 0.01; p < 0.05, respectively). At week 18, when locomotor function of the stretched animals recovered back to pre-stretch levels, the ROM for both previously affected joints had improved significantly (p < 0.01) from week 15 and was no longer different from the controls. This suggests that in-cage activity was sufficient to ameliorate the muscle contractures when the animals were not being stretched.

FIG. 6.

Passive end range of motion (ROM). Significant differences are indicated by (*) for knee (A,B) and hip (C,D) angles at end ROM when comparing the Chronic Stretch (ChS) animals with the unstretched control animals at weeks 15 and 18. By week 18, the ChS animals had recovered significantly (^) when compared with week 15. IC, iliac crest. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

Spinal cord and muscle histology

There were no significant differences in the percent spared white matter at the injury epicenter, reported as mean ± standard deviation: AcS 3.97 ± 2.33, ChS 2.64 ± 1.62, control 3.77 ± 2.6. TA, GM, and BF muscles were analyzed for persistent signs of overt injury induced by repetitive or excessive strain during stretching and that might contribute to the observed locomotor deficits. We also measured CSA of muscle fibers to assess whether muscle stretch resulted in hypertrophy because it is a potent mechanical stimulus for muscle growth in non-SCI models.17 The results of the histological analysis are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Skeletal Muscle Histological Analysis

| Muscle Fiber CSA (μm2) | |||

| Tibialis Anterior | Gastrocnemius | Biceps Femoris | |

| Acute Stretch (n = 10) | 573.05 ± 99.00 | 730.04 ± 139.75 | 616.89 ± 154.77 |

| Chronic Stretch (n = 9) | 531.52 ± 116.70 | 598.83 ± 122.42* | 468.38 ± 100.84^ |

| Control (n = 3) | 521.55 ± 82.26 | 871.96 ± 261.74 | 684.55 ± 118.28 |

| Centralized nuclei count (% of MF analyzed) | |||

| Tibialis Anterior | Gastrocnemius | Biceps Femoris | |

| Acute Stretch (n = 10) | 3.53 ± 0.02 | 3.457 ± 0.02 | 1.669 ± 0.01 |

| Chronic Stretch (n = 9) | 2.9 ± 0.01 | 2.738 ± 0.01 | 3.294 ± 0.03 |

| Control (n = 3) | 2.01 ± 0.01 | 3.456 ± 0.01 | 4.283 ± 0.03 |

| Collagen area (mm2) | |||

| Tibialis Anterior | Gastrocnemius | Biceps Femoris | |

| Acute Stretch (n = 10) | 0.093 ± 0.04 | 0.071 ± 0.03 | 0.127 ± 0.03 |

| Chronic Stretch (n = 9) | 0.121 ± 0.5 | 0.073 ± 0.02 | 0.146 ± 0.03 |

| Control (n = 3) | 0.112 ± 0.17 | 0.064 ± 0.01 | 0.116 ± 0.03 |

CSA, cross-sectional area; MF, muscle fiber.

Chronic Stretch (ChS) gastrocnemius CSA significantly different from Control.

ChS biceps femoris CSA significantly different from Control.

The percentage of muscle fibers that contained centralized nuclei was also not significantly different for any group. We could not identify any areas of fibrosis (tissue scarring) in the three muscles examined, and quantitative analysis of collagen revealed no significant differences between the groups. CSA of TA, GM, and BF muscle fibers in the AcS group were not different from injured, unstretched controls. One-way ANOVA showed significant group difference in CSA of GM (F = 7.5, df = 2,19, p < 0.005) and BF (F = 15.8, df = 2,19, p < 0.001), indicating that the ChS group had significantly decreased GM and BF fiber CSA compared with either the AcS group or the controls; however, no differences in TA fiber CSA were found. These observations suggest that the period of very low activity (weeks 12–15) for the ChS animals resulted in a decrease in muscle fiber CSA (disuse atrophy) in the extensor muscles analyzed.

Discussion

These results extend our previous observations of the stretching phenomenon20,22 into a more clinically relevant moderately severe animal model of contusive SCI. There are four primary findings in this study. First, locomotor function of animals with chronic SCIs is highly vulnerable to the effects of stretching (BBB scores of 0 for all nine animals after the second week of stretching) despite the fact that locomotor recovery of the ChS group had plateaued for more than 4 weeks before the initiation of the stretching protocol. Second, 4 or 5 weeks of stretching did not result in persistent, long-lasting changes in either overground locomotion in the chronic and acute SCI groups as shown by the BBB scores or by shallow water walking because the HAT and IHA “joint” excursions achieved significant recovery. Third, in the chronic group, EMG responses to magnetic stimulation of the base of the tail (MEMRs) remained low for as long as 5 weeks after the last stretching session suggesting a persistent decrease in motoneuron or circuit excitability. Finally, we could find no signs of muscle damage in either AcS or ChS animals that could explain, even in part, the deficits in locomotor function, suggesting that stretching does not result in overt muscle damage that could explain its negative impact on locomotor function; thus, neurological mechanisms are likely underlying the locomotor deficits.

Unlike human subjects with SCI, animals with only 5–10% spared white matter achieve significant locomotor recovery.24 One of the biggest differences between human subjects and rats with SCIs is the state of mobility after the traumatic event. Experimental animals are returned to their home cages (usually with a cage mate) where they move about freely. Flaccid paralysis resolves, in-cage activity increases, and the functional forelimbs provide a built-in training mechanism leading to significant locomotor recovery.24 On the other hand, animals immobilized in wheelchairs after SCI have significant deficits in locomotor function compared with unrestrained SCI rats.20

In this study, we found that the overnight, in-cage activity (which does not indicate hindlimb involvement in stepping) of the AcS animals remained consistently high throughout the 5 weeks of stretching, potentially contributing to their quick recovery from the stretch-induced deficits on the weekends. Overnight activity of the ChS animals, on the other hand, significantly decreased during the weeks of stretching, most likely because these animals used only their forelimbs for propulsion because stretching temporarily negated the hindlimb recovery achieved in the first 10 weeks after SCI. These results support the concept that hindlimb function associated with higher BBB scores facilitates in-cage distance traveled.

After the last stretching session, animals in both stretching groups recovered significant locomotor function back to control/pre-stretch levels within 2 weeks. In our previous stretching study, the animals also achieved substantial locomotor recovery; however, persistent and significant deficits in function remained.22 The previous study involved 8 weeks of stretching as opposed to 4 or 5 weeks in the current study. This suggests that longer periods of immobility within the perceived critical window of opportunity for functional locomotor recovery may have resulted in an inability to achieve “full” recovery when returned to standard double-housing. In addition, animals in the previous study had milder SCIs and higher average BBB scores of 14 compared with 11 in the current study. Thus, the persistent deficits observed in the previous study may be reflected only in the finer aspects of locomotion, such as hindlimb-forelimb coordination (BBB scores of 11 vs. 14), which would not have been discerned in the current study because of the more severe injury and lower functional plateau.

The focus of PTs who employ stretching for patients with SCI is to maintain the extensibility of soft tissues and preserve or regain ROM in joints vulnerable to the development of contractures.31 Based on a systematic review of stretching for the treatment and prevention of contractures in persons with neurological conditions, however, stretching therapies did not result in clinically important improvements in joint mobility.32 The authors suggest that a potential limitation in the practice of stretching is a lack of standardized protocols or specific recommendations for the frequency, intensity, and duration of stretch to achieve the desired outcomes.

One animal study investigated the effectiveness of different stretching characteristics (manipulation of torque intensities and duration) to manage the development of knee contractures in animals with complete thoracic spinal cord transections.33 They found that maximizing both the torque and the duration of stretch resulted in the most significant improvements in contractures (increased ROM). Thus, the authors suggest that high intensity-long duration static stretching may be an effective modality to investigate in clinical trials. This study, however, did not consider the potential adverse neurological effects of intense, long-duration stretch.

In the present study, when a higher perceived force was needed to achieve a normal end ROM during the 4th and 5th weeks of stretching in the AcS group, the negative impact on locomotor function became significant. It appears that the optimal stretching characteristics for treatment and prevention of muscle contractures might also be the most negative for locomotor function after an incomplete contusive SCI.

Despite the fact that we carefully monitor the hindlimb position for each stretching maneuver and received consultation from experienced human PTs, we wanted to investigate whether the negative effects of stretching might be partly attributed to overt and persistent muscle trauma. Muscle fibers injured by strain undergo robust regeneration via the activation of satellite cells.34,35 Because the nuclei are located peripherally in the myocyte, it is easy to identify fibers that have been injured, because regenerating/regenerated muscle fibers have centralized nuclei, which persist for at least 4 months.36 We found no significant group differences in the number of muscle fibers containing centralized nuclei.

Collagen deposition in the extracellular matrix around muscle fibers is another indication of trauma, in particular after repetitive muscle strain.37 In addition, myocytes that experience persistent or repetitive trauma will eventually fail to regenerate, and the debris of dead muscle fibers will be removed and replaced with collagen, resulting in easily recognizable and permanent fibrosis or scarring.34 Thus, we quantified collagen in the muscles but again found no differences between the three groups. We therefore concluded that our stretching protocol does not result in frank and persistent muscle damage that can help explain the significant locomotor deficits that we observe in our animals.

The severe locomotor dysfunction, significantly reduced in-cage activity, and contractures (reduced passive end ROM of the knee and hip) in the ChS rats were accompanied by significant decreases in the CSA of GM (ankle extensor) and BF (knee flexor/hip extensor) muscles, suggesting disuse atrophy. The TA (ankle flexor) muscle, however, did not undergo significant atrophy. Previous studies found a similar pattern of muscle atrophy as a result of disuse affecting extensor muscles more than flexors.38,39

It is worth considering, however, that muscle stretch does not affect only the muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Stretching will also affect group Ia and II muscle spindle afferents, potentially increasing their threshold for firing (decreasing their sensitivity to stretch). Given their importance for the generation/recovery of locomotion after SCI,40 changes to muscle spindle sensitivity is one potential explanation for the stretching phenomenon. In addition to Ia and group II muscle spindle afferents, muscles are innervated by small diameter thinly myelinated and unmyelinated group III and IV afferents that are activated by mechanical stimuli such as contraction and muscle stretch.41–44 Specifically, Cleland and colleagues43 have identified stretch-sensitive free nerve endings of group III and IV fibers that mediate powerful reflex inhibition of the homonymous muscles in an animal model of clasp-knife reflex. This same group has also found force-sensitive interneurons that receive input from group III and IV afferents and that produce rapid and sustained inhibition of motoneuron output.45

Group III and IV afferents have also been implicated in the inhibition of motor output (central fatigue) during exercise in humans.46,47 Thus, it is probable that the stretching protocol we administer to animals with SCI activates group III and IV afferents that in turn should have an inhibitory affect on motor circuitry resulting in dramatic drops in locomotor function. Whether or not this mechanism is responsible, in whole or in part, for our current observations remains to be determined.

After an incomplete SCI in rats, the sprouting of spared descending axons is thought to mediate at least some of the remarkable functional recovery.48 On the other hand, primary afferent sprouting, particularly of C and Aδ fibers, has been associated with neuropathic pain and autonomic dysreflexia.49,50 It is possible that increased arborization of these primary afferents also leads to the more robust inhibitory effects of group III and IV afferents over motor output, thus explaining why animals with stabilized locomotor recovery (ChS group) are so vulnerable to the negative effects of stretching. If this hypothesis is confirmed, it is likely that the stretching phenomenon we observe in our rats has high clinical relevance.

Harvey and associates51 investigated the amount of torque PTs apply during regular stretching sessions and found that some therapists applied torques that were two to six times higher than what is tolerated by sensate individuals. In addition, the authors discuss the possibility that patients with SCI regularly generate very high torques around their hip joints while dressing in a seated position. For the majority of patients with SCI, stretching that activates nociceptive afferents would not result in the perception of pain because of the loss of sensory function below the level of injury. Existing evidence suggests, however, that transmission of nociceptive signals results in a multitude of unfavorable effects over the locomotor circuitry52,53 that has an otherwise high capacity for retraining, given the appropriate proprioceptive feedback.54–57

Conclusion

Stretching has been adopted as a therapy in the rehabilitation regime for patients with SCI based in part on past evidence from animal studies that focused on soft tissues undergoing maladaptive changes as a result of immobilization.16 While more recent clinical investigations into stretching therapy reveals its general ineffectiveness for the treatment of muscle contractures in patients with SCI,14,32 current and previous findings from our laboratory suggest that stretching is detrimental to locomotor function in animals with mild to severe SCIs at both acute and chronic time points. The clinical relevance of our results is yet to be determined, but these findings suggest strongly that the neurological effects of muscle stretch warrants consideration as being potentially detrimental to the function of locomotor circuitry after SCI.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge KSCIRC core staff for providing outstanding technical support: Christine Yarberry, Darlene Burke, Johnny Morehouse and Kim Fentress. We also want to thank Darryn Atkinson, PT and Carie Tolfo, PT from Frazier Rehabilitation Institute for their assistance in establishing stretching maneuvers. In addition we would like to express our appreciation to Sajedah Hindi for sharing her expertise on histological analysis of skeletal muscle. Thank you to our current and former lab members who participated in daily stretching sessions of the animals: Kathryn Deveau, Kathryn Harman, Kelsey Stipp, Chad Stepp and Sarah Dudley.

This work was supported by the Department of Defense (SC110169), the National Institutes of Health (P30 GM104507) and the Kentucky Spinal Cord and Head Injury Research Trust.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Dudley-Javoroski S., and Shields R.K. (2008). Muscle and bone plasticity after spinal cord injury: review of adaptations to disuse and to electrical muscle stimulation. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 45, 283–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray K.C., Nakae A., Stephens M.J., Rank M., D'Amico J., Harvey P.J., Li X., Harris R.L., Ballou E.W., Anelli R., Heckman C.J., Mashimo T., Vavrek R., Sanelli L., Gorassini M.A., Bennett D.J., and Fouad K. (2010). Recovery of motoneuron and locomotor function after spinal cord injury depends on constitutive activity in 5-HT2C receptors. Nat. Med. 16, 694–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey P.J., Li Y., Li X., and Bennett D.J. (2006). Persistent sodium currents and repetitive firing in motoneurons of the sacrocaudal spinal cord of adult rats. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 1141–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouad K., Rank M.M., Vavrek R., Murray K.C., Sanelli L., and Bennett D.J. (2010). Locomotion after spinal cord injury depends on constitutive activity in serotonin receptors. J. Neurophysiol. 104, 2975–2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rekling J.C., Funk G.D., Bayliss D.A., Dong X.W., and Feldman J.L. (2000). Synaptic control of motoneuronal excitability. Physiol. Rev. 80, 767–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jankowska E., and Hammar I. (2002). Spinal interneurones; how can studies in animals contribute to the understanding of spinal interneuronal systems in man? Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 40, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen J.B., Crone C., and Hultborn H. (2007). The spinal pathophysiology of spasticity—from a basic science point of view. Acta Physiol. (Oxf) 189, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulenguez P., Liabeuf S., Bos R., Bras H., Jean-Xavier C., Brocard C., Stil A., Darbon P., Cattaert D., Delpire E., Marsala M., and Vinay L. (2010). Down-regulation of the potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 contributes to spasticity after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 16, 302–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietz V. (2010). Behavior of spinal neurons deprived of supraspinal input. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maynard F.M., Karunas R.S., and W.P. Waring W.P., 3rd. (1990). Epidemiology of spasticity following traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 71, 566–569 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strommen J.A. (2013). Management of spasticity from spinal cord dysfunction. Neurol. Clin. 31, 269–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrick J.H., Farmer S.E., and Bromwich W. (2002). Muscle stretching for treatment and prevention of contracture in people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 40, 421–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalyan M., Sherman A., and Cardenas D.D. (1998). Factors associated with contractures in acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 36, 405–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey L.A., Glinsky J.A., Katalinic O.M., and Ben M. (2011). Contracture management for people with spinal cord injuries. NeuroRehabilitation 28, 17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair K.P., and Marsden J. (2014). The management of spasticity in adults. BMJ 349, g4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey L.A., and Herbert R.D. (2002). Muscle stretching for treatment and prevention of contracture in people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 40, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldspink D.F., Cox V.M., Smith S.K., Eaves L.A., Osbaldeston N.J., Lee D.M., and Mantle D. (1995). Muscle growth in response to mechanical stimuli. Am. J. Physiol. 268, E288–E297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams P.E. (1990). Use of intermittent stretch in the prevention of serial sarcomere loss in immobilised muscle. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 49, 316–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cote M.P., Azzam G.A., Lemay M.A., Zhukareva V., and Houlé J.D. (2011). Activity-dependent increase in neurotrophic factors is associated with an enhanced modulation of spinal reflexes after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 28, 299–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caudle K.L., Brown E.H., Shum-Siu A., Burke D.A., Magnuson T.S., Voor M.J., and Magnuson D.S. (2011). Hindlimb immobilization in a wheelchair alters functional recovery following contusive spinal cord injury in the adult rat. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 25, 729–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnuson D.S., Smith R.R., Brown E.H., Enzmann G., Angeli C., Quesada P.M., and Burke D. (2009). Swimming as a model of task-specific locomotor retraining after spinal cord injury in the rat. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 23, 535–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caudle K.L., Atkinson D.A., Brown E.H., Donaldson K., Seibt E., Chea T., Smith E., Chung K., Shum-Siu A., Cron C.C., and Magnuson D.S. (2015). Hindlimb stretching alters locomotor function after spinal cord injury in the adult rat. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 29, 268–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basso D.M., Beattie M.S., and Bresnahan J.C. (1995). A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J. Neurotrauma 12, 1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuerzi J., Brown E.H., Shum-Siu A., Siu A., Burke D., Morehouse J., Smith R.R., and Magnuson D.S. (2010). Task-specificity vs. ceiling effect: step-training in shallow water after spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 224, 178–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guissard N., Duchateau J., and Hainaut K. (2001). Mechanisms of decreased motoneurone excitation during passive muscle stretching. Exp. Brain Res. 137, 163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guissard N., and Duchateau J. (2004). Effect of static stretch training on neural and mechanical properties of the human plantar-flexor muscles. Muscle Nerve 29, 248–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnuson D.S., Trinder T.C., Zhang Y.P., Burke D., Morassutti D.J., and Shields C.B. (1999). Comparing deficits following excitotoxic and contusion injuries in the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord of the adult rat. Exp. Neurol. 156, 191–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caudle K.L., Atkinson D.A., Brown E.H., Donaldson K., Seibt E., Chea T., Smith E., Chung K., Shum-Siu A., Cron C.C., and Magnuson D.S. (2015). Hindlimb stretching alters locomotor function after spinal cord injury in the adult rat. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 29, 268–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jonkers B.W., Sterk J.C., and Wouterlood F.G. (1984). Transcardial perfusion fixation of the CNS by means of a compressed-air-driven device. J. Neurosci. Methods 12, 141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ceglia L., Niramitmahapanya S., Price L.L., Harris S.S., Fielding R.A., and Dawson-Hughes B. (2013). An evaluation of the reliability of muscle fiber cross-sectional area and fiber number measurements in rat skeletal muscle. Biol. Proced. Online 15, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvey L., Herbert R., and Crosbie J. (2002). Does stretching induce lasting increases in joint ROM? A systematic review. Physiother. Res. Int. 7, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katalinic O.M., Harvey L.A., and Herbert R.D. (2011). Effectiveness of stretch for the treatment and prevention of contractures in people with neurological conditions: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 91, 11–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moriyama H., Tobimatsu Y., Ozawa J., Kito N., and Tanaka R. (2013). Amount of torque and duration of stretching affects correction of knee contracture in a rat model of spinal cord injury. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 471, 3626–3636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodine-Fowler S. (1994). Skeletal muscle regeneration after injury: an overview. J. Voice 8, 53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultz E., Jaryszak D.L., and Valliere C.R. (1985). Response of satellite cells to focal skeletal muscle injury. Muscle Nerve 8, 217–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minamoto V.B., Bunho S.R., and Salvini T.F. (2001). Regenerated rat skeletal muscle after periodic contusions. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 34, 1447–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stauber W.T., Knack K.K., Miller G.R., and Grimmett J.G. (1996). Fibrosis and intercellular collagen connections from four weeks of muscle strains. Muscle Nerve 19, 423–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castro M.J., Apple DF, Jr, Hillegass EA, and Dudley GA. (1999). Influence of complete spinal cord injury on skeletal muscle cross-sectional area within the first 6 months of injury. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 80, 373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhong H., Roy R.R., Woo J., Kim J.A., and Edgerton V.R. (2007). Differential modulation of myosin heavy chain phenotype in an inactive extensor and flexor muscle of adult rats. J. Anat. 210, 19–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossignol S., and Frigon A. (2011). Recovery of locomotion after spinal cord injury: some facts and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34, 413–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mense S., and Meyer H. (1985) Different types of slowly conducting afferent units in cat skeletal muscle and tendon. J. Physiol. 363, 403–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleland C.L. and Rymer W.Z. (1990). Neural mechanisms underlying the clasp-knife reflex in the cat. I. Characteristics of the reflex. J. Neurophysiol. 64, 1303–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cleland C.L., Hayward L., and Rymer W.Z. (1990). Neural mechanisms underlying the clasp-knife reflex in the cat. II. Stretch-sensitive muscular-free nerve endings. J. Neurophysiol. 64, 1319–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gladwell V.F., and Coote J.H. (2002). Heart rate at the onset of muscle contraction and during passive muscle stretch in humans: a role for mechanoreceptors. J. Physiol. 540, 1095–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cleland C.L., Rymer W.Z., and Edwards F.R. (1982). Force-sensitive interneurons in the spinal cord of the cat. Science 217, 652–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amann M. (2012). Significance of Group III and IV muscle afferents for the endurance exercising human. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 39, 831–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amann M., Blain G.M., Proctor L.T., Sebranek J.J., Pegelow D.F., and Dempsey J.A. (2011). Implications of group III and IV muscle afferents for high-intensity endurance exercise performance in humans. J. Physiol. 589, 5299–5309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ballermann M., and Fouad K. (2006). Spontaneous locomotor recovery in spinal cord injured rats is accompanied by anatomical plasticity of reticulospinal fibers. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 1988–1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong S.T., Atkinson B.A., and Weaver L.C. (2000). Confocal microscopic analysis reveals sprouting of primary afferent fibres in rat dorsal horn after spinal cord injury. Neurosci. Lett. 296, 65–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagg T. (2006). Collateral sprouting as a target for improved function after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 23, 281–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harvey L.A., McQuade L., Hawthorne S., and Byak A. (2003). Quantifying the magnitude of torque physiotherapists apply when stretching the hamstring muscles of people with spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 84, 1072–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hook M.A., Huie J.R., and Grau J.W. (2008). Peripheral inflammation undermines the plasticity of the isolated spinal cord. Behav. Neurosci. 122, 233–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferguson A.R., Huie J.R., Crown E.D., Baumbauer K.M., Hook M.A., Garraway S.M., Lee K.H., Hoy K.C., and Grau J.W. (2012). Maladaptive spinal plasticity opposes spinal learning and recovery in spinal cord injury. Front. Physiol. 3, 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith A.C., Mummidisetty C.K., Rymer W.Z., and Knikou M. (2014). Locomotor training alters the behavior of flexor reflexes during walking in human spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 112, 2164–2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lovely R.G., Gregor RJ, Roy RR, and Edgerton VR. (1986). Effects of training on the recovery of full-weight-bearing stepping in the adult spinal cat. Exp. Neurol. 92, 421–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knikou M., and Mummidisetty C.K. (2014). Locomotor training improves premotoneuronal control after chronic spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 111, 2264–2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Behrman A.L., and Harkema S.J. (2000). Locomotor training after human spinal cord injury: a series of case studies. Phys. Ther. 80, 688–700 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]