Abstract

Opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used commonly to manage pain in the early phase of spinal cord injury (SCI). Despite its analgesic efficacy, however, our studies suggest that intrathecal morphine undermines locomotor recovery and increases lesion size in a rodent model of SCI. Similarly, intravenous (IV) morphine attenuates locomotor recovery. The current study explores whether IV morphine also increases lesion size after a spinal contusion (T12) injury and quantifies the cell types that are affected by early opioid administration. Using an experimenter-administered escalating dose of IV morphine across the first seven days post-injury, we quantified the expression of neuron, astrocyte, and microglial markers at the injury site. SCI decreased NeuN expression relative to shams. In subjects with SCI treated with IV morphine, virtually no NeuN+ cells remained across the rostral-caudal extent of the lesion. Further, whereas SCI per se increased the expression of astrocyte and microglial markers (glial fibrillary acidic protein and OX-42, respectively), morphine treatment decreased the expression of these markers. These cellular changes were accompanied by attenuation of locomotor recovery (Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan scores), decreased weight gain, and the development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (increased tactile reactivity) in morphine-treated subjects. These data suggest that morphine use is contraindicated in the acute phase of a spinal injury. Faced with a lifetime of intractable pain, however, simply removing any effective analgesic for the management of SCI pain is not an ideal option. Instead, these data underscore the critical need for further understanding of the molecular pathways engaged by conventional medications within the pathophysiological context of an injury.

Keywords: : cell death, hyperalgesia, locomotor recovery, opioid-induced, opioids, spinal cord injury

Introduction

In the acute phase of spinal cord injury (SCI), pain and sensitivity associated with trauma to spinal cord, as well as concomitant injuries, are typically treated with opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).1 Indeed, Neighbor and associates2 reported that 48% of 540 trauma patients received opioids within hours of arrival to the emergency department. Effective treatment of pain in this early phase is not only essential for ethical reasons, but there is also evidence to suggest that early treatment of patients with acute pain is paramount in minimizing the risk of chronic pain development.3,4 Unfortunately, however, although mitigation of pain is vital, our animal studies suggest that opioid use may be contraindicated in the acute phase of SCI.

We have shown that even a single dose of intrathecal (IT) morphine, administered in the acute phase of a rodent spinal injury, attenuates locomotor recovery, increases symptoms of pain in the chronic stage of injury, increases death and autophagia, reduces general health, and significantly increases the size of the spinal lesion relative to vehicle SCI controls.5–7 Moreover, these adverse effects are not limited to IT morphine administration. Woller and colleagues8 showed that self-administration of high doses of intravenous (IV) morphine, a more clinically relevant route of administration, also significantly undermined locomotor recovery after injury.

In fact, SCI and opioids share several common features that have been linked to impaired recovery of function, as well as the development of pain.9 For example, apoptosis, resulting from N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) neurotoxicity, occurs after both opioid administration and SCI.10–13 In the acute phase of SCI, the increase in cell death is mediated, in part, by elevated glutamate levels and NMDAR activation.14 Similarly, extended morphine administration is thought to contribute to NMDAR excitability via upregulation of protein kinase C gamma (PKCγ).15–19

Further, microglial activation resulting from opioid receptor binding, as well as SCI, causes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α.20–22 The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines further stimulates microglia to produce more pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to mechanical hypersensitivity.21,23–25 In addition, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNFα, have been implicated in neuronal apoptosis after SCI.26–29 In sum, opioid administration may synergistically contribute to the pathology of SCI to increase the development of pain and cell death, and decrease functional recovery.

The current study explores the implications of opioids further with IV morphine administration. First, we aimed to determine whether IV morphine administration increases lesion size after SCI. Extending these analyses, we also examined whether morphine affected the expression of specific cell populations (neurons, astrocytes, and microglia) at the spinal level. Simulating self-administration behavior,8 subjects were administered an escalating dose of IV morphine across the first seven days post-injury. We found that IV morphine administration unequivocally reduces functional recovery in the rodent model of SCI, as well as decreasing neuronal and glial markers at the injury site.

Methods

Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats obtained from Harlan (Houston, TX) were used as subjects. Animals were 90–110 days old (300–350 g) and were individually housed in Plexiglas bins (45.7 [length] × 23.5 [width] × 20.3 [height] cm) with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were maintained on a 12-h light-dark cycle. Except where noted, all behavioral testing occurred during the light portion of the cycle.

All of the experiments were reviewed and approved by the institutional care committee at Texas A&M University and all National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for the care and use of animal subjects were followed.

Surgical procedure

Jugular catheterization

To allow for the administration of morphine, all subjects were implanted with a jugular catheter.8,30 Rats were anesthetized using a combination of ketamine 80 mg/kg and xylazine 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally (IP). While under anesthesia, a catheter consisting of a length of PE50 tubing was inserted into and tied to the jugular vein. Using an 11-gauge stainless steel tube as a guide, this catheter was passed subcutaneously through the body of the animal so that it exited in the back. A back mount cannula pedestal (model 313-00BM-10-SPC; Plastics One Inc., Roanoke, VA) was then implanted subcutaneously and connected to the catheter. The back mount exited the skin between the scapulae and was covered with a dust cap. All incisions were closed using VetBond.

For the first 24 h after the surgical procedure, the rats were housed in a recovery room maintained at 26.6°C. The subjects were treated with penicillin G potassium 100,000 U/kg (IP) immediately after the operation and again 2 days later. To help maintain hydration, the subjects were also given 3.0 mL of saline (0.9%, IP) after the operation. During the 5-day recovery period after the operation and before any drug treatments, the catheters were flushed with heparinized saline (100 U/mL, 0.25 mL).

Contusion SCI

Five days after the implantation of the jugular catheter, subjects were given a moderate contusion injury. Briefly, subjects were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane (5% to induce anesthesia and 2–3% for maintenance). The subject's back was shaved and disinfected with iodine, and a 5.0 cm incision was made over the spinal cord. Two incisions were made along the vertebral column, on each side of the dorsal spinous processes, extending about 2 cm rostral and caudal to the T12 segment. Muscle and connective tissue were then dissected to expose the underlying vertebral segments. Musculature around the transverse processes was cleared to allow for clamping of the vertebral spinal column. Next, the dorsal spinous process at T12 was removed, and the spinal tissue exposed. The dura remained intact.

The vertebral column was fixed within the Infinite Horizons impactor (Precision Systems Instrumentation) using two pairs of Adson forceps. A moderate injury was produced using an impact force of 150 kdynes and a 1 sec dwell time. The wound was closed with Michel clips. Sham subjects received a laminectomy only.

For the first 24 h after the operation, the rats were housed in a recovery room as described previously. All subjects were treated with penicillin G potassium 100,000 U/kg (IP) immediately after the operation and again two days later. To help maintain hydration, the subjects were also given 3.0 mL of saline (0.9%, IP) after the operation. Subjects’ bladders were expressed manually in the morning (8:00–9:30 am) and evening (6:00–7:30 pm) until they regained bladder control, which was defined as three consecutive days with an empty bladder at the time of expression.

Drug administration

Morphine was administered intravenously (IV) beginning 24 h after the contusion or sham injury. Half of the subjects (n = 9, for the contused and sham groups) were given 5 mg morphine/infusions/h through the back mount attached to the jugular catheter for seven days on the following schedule: 10 mg (days one and two), 20 mg (days three and four), and 30 mg (days five, six, and seven). Control animals (n = 9, for the contused and sham groups) received an equivalent number (and volume) of infusions of 0.9% saline.

The doses of morphine used in this study were derived from previous studies testing analgesia and self-administration.8 While these doses are higher than those used clinically (up to 120 mg per day), doses used in rodent studies cannot be equated to those applied in the clinical setting. The lethal dose (LD)50 is more than 100-fold higher for rats than humans,31 and although some studies suggest that the plasma half-life of morphine is very similar for rats and humans,32 the Kp,uu (ratio between brain and blood unbound drug concentrations) and active influx and efflux processes differ across species and conditions.33–35 For example, P-glycoproteins actively transport morphine out of the central nervous system in rats, but this efflux transporter appears to play little role in brain drug concentrations in humans.36 Notably, P-glycoproteins are upregulated after a rodent spinal contusion injury.37 Further, in the clinical setting, supplemental analgesics, such as NSAIDS, will increase the elimination half-life of morphine. For example, Diclofenac (2-[(2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino]benzene acetate), an effective and frequently prescribed NSAID, is metabolized by the UGT2B7 (UDP-glucuronosyltransferases 2B7). UGT2B7 is the only known enzyme to catalyze the formation of the 6-O-glucuronides of opiates.38 King and coworkers39 demonstrated that diclofenac inhibited the glucuronidation of morphine. Drug interactions will alter the pharmacokinetics of opioids administered in the clinical setting.

In the current study, the escalating dose of morphine administration across days was based on the self-administration behavior previously described for this rodent model of SCI. While lower doses of morphine also undermine recovery of function after SCI, these doses were chosen because they produce robust effects on functional recovery with a small sample size (n = 4 per experimental condition8).

Assessment of the analgesic efficacy of morphine

Sensory reactivity tests were conducted on days one, three, five, and seven before administration of drugs and approximately 30 min after the last infusion of morphine, allowing for the assessment of opioid-induced hyperalgesia/allodynia and tolerance,40,41 respectively. Thermal (heat) reactivity was assessed using the tail-flick test. Subjects were placed in clear Plexiglas tubes with their tail positioned in a 0.5 cm deep groove, cut into an aluminum block, and allowed to acclimate to the apparatus (IITC Inc., Life Science, CA) and testing room for 15 min. The testing room was maintained at 26.5°C.

Thermal thresholds were then assessed, using a halogen light that was focused on the rat's tail. Before testing, the temperature of the light focused on the tail was set to elicit a baseline tail flick response in 3–4 sec (average) in intact rats. This pre-set temperature was maintained across all subjects. In testing, the latency to flick the tail away from the radiant heat source (light) was recorded. If a subject failed to respond, the test trial was automatically terminated after 8 sec of heat exposure, to avoid tissue damage. Two tests occurred at 2-min intervals; the tail flick latencies recorded on the second test were used as indices of nociceptive reactivity.

Mechanical reactivity was assessed using von Frey stimuli (Semmes-Weinstein Anesthesiometer; Stoelting Co., Chicago, IL) applied to the plantar surface of the hindpaws. Subjects were placed into the clear Plexiglas tubes with both hindlimbs outside the tube and hanging freely. After a 15-min acclimation period, the von Frey stimuli were applied sequentially at approximately 2-sec intervals until subjects withdrew the paw and vocalized. If no response was observed, testing was terminated at a force of 300g. Each subject was tested twice on each foot in a counterbalanced ABBA order. Test sequences were spaced 2 min apart.

Assessment of recovery

Locomotor behavior was assessed using the Basso-Beattie-Bresnahan (BBB) rating scale42 in an open enclosure (99 cm diameter and 23 cm deep) on the day after the contusion injury. The subjects were acclimated to the apparatus for 5 min per day for three days before the surgical procedure. At 24 h after the operation, each subject was placed in the open field and observed for 4 min to assess locomotor function. All observers had high intra- and interobserver reliability (all r's >0.89) and were blind to the subjects’ experimental treatment.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Twenty-four hours after the final administration of morphine, on day eight post-injury, 12 subjects (Sham + Vehicle [n = 3], Sham + Morphine [n = 3], SCI + Vehicle [n = 3], SCI + Morphine [n = 3]) were anesthetized deeply with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and perfused intracardially with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. A 1 cm section of spinal cord surrounding the lesion center was removed and post-fixed in 4% PFA for 2 h and then transferred to 30% sucrose for cryoprotection. After a minimum of 72 h in sucrose, the section of cord was frozen in a cryomold with optimal cutting temperature compound. Twenty micron coronal sections were cut with a cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Sections were then used for staining with cresyl violet for Nissl substance and Luxol® fast blue for myelin43,44 or immunofluorescence labeling.

Luxol fast blue and cresyl violet

For these sections, the total cross-sectional area of the cord and spared tissue was assessed across the rostral-caudal extent of the lesion using Neurolucida software (MicrobrightField, Williston, VT).7 Three sections were traced and analyzed to derive tissue sparing at the center of the lesion (−600, 0, + 600 μm from lesion center), as well as rostral (−1200, 1800, 2400 μm) and caudal (+1200, 1800, 2400 μm) to the lesion center. To determine the area of lesion, an observer who was blinded to the experimental treatments traced around the boundaries of cystic formations and areas of dense gliosis.7 Nissl-stained areas that contained neurons and glia of approximately normal densities denoted residual gray matter. White matter was judged spared in myelin-stained areas lacking dense gliosis and swollen fibers. These analyses yielded three parameters for each section: white matter area, gray matter area, and lesion area.

To control for variability in section area across subjects, we applied a correction factor derived from our sham vehicle animals. This correction factor45 was based on section widths and was multiplied by all area measurements to standardize area across analyses. By standardizing areas across sections, we were able to estimate the degree to which tissue is “missing” (i.e., tissue loss from atrophy, necrosis, or apoptosis). An accurate assessment of the degree to which a treatment has impacted, or lesioned, the cord includes both the remaining “damaged” tissue as well as resolved lesioned areas. When we sum the amount of “missing” tissue and the “damaged” area, we derive an index of the relative lesion (% relative lesion) in each section that is comparable across sections. We can also compute the relative percent of gray and white matter remaining in each section, relative to sham controls.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was used to determine the effect of SCI and morphine on the expression of neurons, microglia, and astrocytes. The spinal cord sections were washed (3 × 10 min) with 1X PBS, then incubated in blocking solution (3% normal goat serum, 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 60 min at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with markers for neurons (NeuN, 1:400, Millipore, Bedford, MA; NF, 1:300, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein [GFAP], 1:500, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA; S-100, 1:300, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or microglia (OX42/CD11b/c, 1:1000, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA; IBA1, 1:300, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) overnight in blocking solution at room temperature or 4°C (depending on the primary antibody).

The following day, all slides were washed in cold PBS, and incubated in the appropriate Alexa fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse, 1:300; Invitrogen, Eugene) prepared in blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature. After another series of washes in PBS (3 × 15 min), the slides were mounted with Prolong Gold anti-fading mounting medium with DAPI (Life Technologies, NY). To provide converging evidence for neurotoxicity, a subset of the slides were also stained with Fluoro-Jade C (ATT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA).

After washing in PBS, as described above, the slides were transferred to a 0.06% potassium permanganate solution for 10 min at room temperature. The sections were then rinsed in distilled water and immersed in a 0.001% Fluoro-Jade® C working solution for 10 min. After rinsing the slides in distilled water (3 × 1 min), the slides were incubated with DAPI for 15 min. The sections were air-dried overnight, immersed in xylene (3 × 1 min), and cover-slipped.

Digital image analyses were performed using the basic densitometric thresholding features of a Virtual Tissue 2D program (Microbrightfield Biosciences, Williston, VT) and Image J (National Institutes of Health). Contiguous images of the spinal sections were captured using the Virtual Tissue 2D system at 4X magnification. The Virtual Tissue 2D program aligns, stitches, and blends the section together into a montage, providing a complete image of the total lesion area and spared tissue.

Using Image J software, the perimeter of each lesion was digitally outlined, and background labeling was subtracted from all images. For quantification of neurons, with Image J, the size and circularity of the target particles were defined, and the counts generated by the program were recorded. For quantification of astrocytes and Fluoro-Jade C expression, a threshold value was obtained for each image ensuring that all labeled cells were selected (i.e., target area). The magnitude of Alexa fluor expression was reported as the proportional area—i.e., ratio of target to scan area.

Because the microglia in the contused sections were densely stacked, we used confocal microscopy (Olympus FV300 confocal microscope with a Plan Apo N 60 to acquire image stacks throughout the z plane of the section) coupled with unbiased stereology (StereoInvestigator, Microbrightfield Biosciences, Williston, VT) to quantify expression. For these analyses, a digital point grid was randomly overlaid on each image, and the number of cells falling within the tissue area were recorded. Separate counts of ramified (quiescent) or amoeboid (activated) microglia were derived.

An average number of 110-130 sites per section were counted for three sections across the center of the injury only. The following parameters were used: height of optical dissector, 15 μm; average grid size, 225 × 225 μm2; counting frame size, 60 × 60 μm2; and section thickness, 20 μm. Z-series images were taken with an interstack interval of 1 μm. Bandpass filter and laser settings were optimized on control tissue and then held constant for the duration of the experiment.

Statistical analyses

Comparisons between the effects of morphine on recovery of function and immunohistochemical end-points were analyzed using mixed design analysis of variants (ANOVAs). Significant effects were analyzed further with pair-wise one way ANOVAs. In both the text and figures, all data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Locomotor scores were transformed to help assure that the data were amendable to parametric analyses.46 This transformation pools BBB scores 2–4, removing a discontinuity in the scale. The transformation also pools scores from a region of the scale (14–21) that is seldom used for a moderate contusion injury. By pooling these scores, we obtain an ordered scale that is relatively continuous with units that have approximately equivalent interval spacing. Meeting these criteria improves the justification for parametric statistical analyses and increases statistical power.

Results

Assessment of the analgesic efficacy of morphine

Development of tolerance with repeated opioid administration

Morphine produced robust analgesia on the test of thermal reactivity. When administered 24 h after a sham or contusion injury, all animals reached the maximum 8-sec tail-flick latency, leaving the tail under the hot light until the experimenter terminated the trial. An ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of drug condition (F (1, 32) = 28.45, p < 0.05). Subjects treated with morphine displayed robust analgesia, with no effect of surgery on the tail-flick response. The analgesic effect of morphine persisted across the seven days of administration (Fig. 1A).

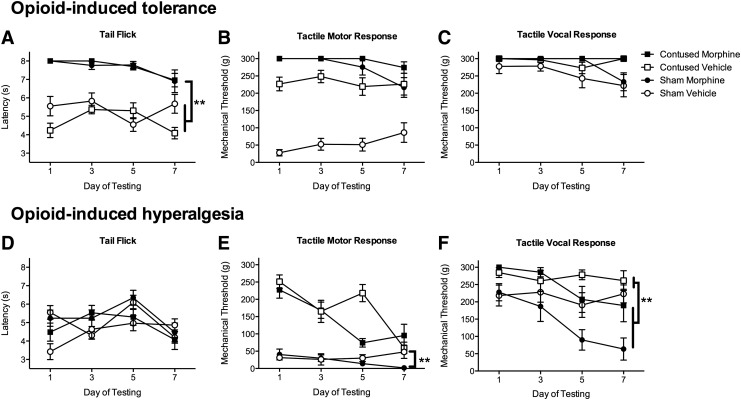

FIG. 1.

Morphine produced robust analgesia on the tests of thermal (A) and tactile (B,C) reactivity. Despite the escalating dose of morphine administered across days, there was a non-significant trend for a reduction in the efficacy of the drug on the tail-flick test (A) in both sham and contused subjects by day seven of administration. Conversely, while hyperalgesia was not evident on the test of thermal reactivity (D), it was evident on the test of tactile reactivity (D,E). Subjects treated with morphine displayed lower tactile reactivity thresholds for both motor (E) and vocal (F) responses after 5–7 days of morphine administration, compared with vehicle controls. n = 9, **p < 0.05.

There was a main effect of morphine treatment, relative to vehicle controls (F (1, 32) = 156.53, p < 0.0001). Although efficacious, however, the analgesia produced by morphine waned across days, indicating the development of tolerance to this drug. By day seven, sham and contused rats, while still showing increased tail flick latencies relative to vehicle-treated controls, no longer reached the maximum tail flick latency of 8 sec (Fig. 1A). This is despite treatment with 30 mg of morphine. An ANOVA showed an effect of day of treatment (F (3, 32) = 3.54, p < 0.05), but no interactions were significant (F's < 3.0, p > 0.05).

With mechanical stimulation, there was no evidence of tolerance developing across days (Fig. 1B, 1C). Morphine produced robust analgesia in both contused and sham subjects across the administration period. An ANOVA revealed significant main effects of drug treatment (F (1, 32) = 82.81, p < 0.0001), surgery (F (1, 32) = 47.97, p < 0.0001), and a Surgery × Drug interaction (F (1, 32) = 37.97, p < 0.0001) on the motor response to mechanical stimulation. Contused subjects displayed significantly less tactile reactivity than sham controls across the seven days of testing (Fig. 1B). Similarly, recording vocalization to the mechanical stimuli, contused animals were less reactive than sham controls (F (1, 32) = 8.7, p < 0.05, Fig. 1C). Again, morphine treatment significantly increased the vocalization response threshold (F (1, 32) = 4.90, p < 0.05), and there was no effect of surgery on the morphine-induced analgesia.

Development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia

Sensory reactivity was assessed before the daily administration of morphine to monitor the development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. In the absence of active morphine-induced analgesia, all animals exhibited similar tail-flick latencies regardless of experimental condition. Tail-flick latencies did not change across the seven-day treatment period (Fig. 1D).

On the test of mechanical reactivity, however, there was evidence for opioid-induced hyperalgesia (Fig. 1E). First, as found for the assessment of tolerance, contused animals tend to be less reactive to mechanical stimuli, and there was a significant main effect of surgery on withdrawal responses (F (1, 32) = 38.54, p < 0.05). Across the seven days of testing, both sham and contused animals treated with morphine began withdrawing their hindlimb at lower forces. Sham animals treated with morphine, by day seven, were more reactive to the mechanical stimulation than sham animals treated with saline. There was a significant effect of day of testing (F (3, 96) = 23.73, p < 0.05), and Day × Drug (F (3, 96) = 5.93, p < 0.05) and Day × Surgery × Drug (F (3, 96) = 5.48, p < 0.05) interactions. These results indicate morphine treatment is leading to the development of pain.

Similarly, for vocalizations in response to tactile stimulation, contused subjects were less reactive than shams (F (1, 32) = 12.61, p < 0.05). As can be seen in Fig. 1F, however, morphine treatment across days led to a significant decrease in the threshold required to elicit a vocalization response (F (1, 32) = 9.68, p < 0.05), and this effect was greatest in the sham animals (F (1, 32) = 4.40, p < 0.05). There was a significant Day × Drug interaction (F (3, 96) = 6.89, p < 0.05) across the seven days of testing: hyperalgesia developed in subjects treated with morphine.

Assessment of recovery

Morphine significantly attenuated locomotor recovery

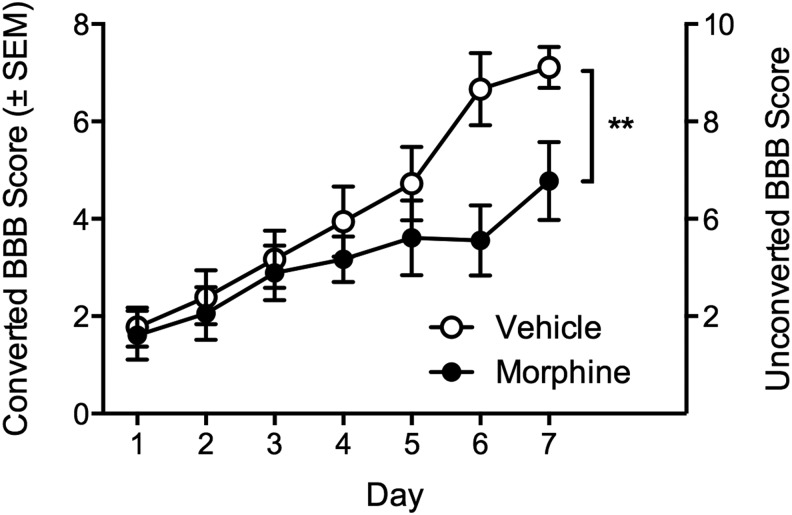

Replicating previous studies, contused rats treated with morphine recovered significantly less locomotor function over the seven-day administration period, relative to vehicle-treated SCI controls (F (5, 75) = 5.27, p < 0.05, Fig. 2). BBB scores were balanced on day one post-injury (converted BBB scores, 1.77 ± 0.40 and 1.61 ± 0.50 for the vehicle and morphine-treated groups, respectively), but by day seven, contused subjects treated with vehicle recovered to an average converted BBB score of 7.11 ± 0.42, while those treated with morphine recovered to 4.77 ± 0.80. All sham rats, irrespective of treatment, had a converted BBB score of 12 (unconverted BBB score of 21) throughout the seven-day post-operation assessment period.

FIG. 2.

Despite balanced Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan (BBB) scores on day one post-injury, morphine significantly undermined recovery of locomotor function relative to vehicle-treated controls. n = 9, **p < 0.05. SEM, standard error of the mean.

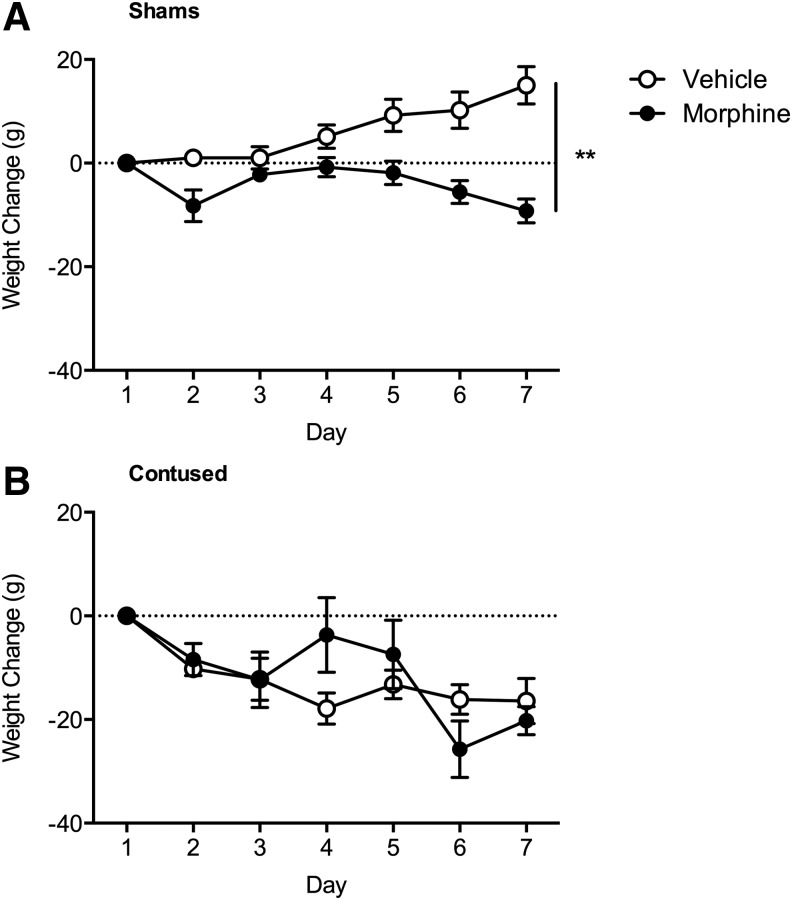

Morphine significantly decreased weight gain

Commensurate with previous studies,7,8,30 both surgery and morphine administration significantly affected weight gain (Fig. 3). There was a main effect of surgery (F (1, 32) = 24.18, p < 0.05), a Day × Surgery (F (6, 192) = 9.88, p < 0.05), Day × Drug (F (6, 192) = 6.59, p < 0.05), and a Day × Surgery × Drug (F (6, 192) = 2.57, p < 0.05) interaction. All contused subjects lost weight over the initial seven days post-surgery, irrespective of drug treatment, relative to sham controls. For the sham subjects, however, post hoc analyses indicated that sham animals treated with morphine weighed significantly less than sham animals treated with vehicle (p < 0.05).

FIG. 3.

Intravenous morphine undermined weight gain in sham (A) subjects. Irrespective of drug treatment condition, the subjects with spinal cord injury lost weight during the first week of recovery (B). n = 9, **p < 0.05.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Morphine significantly increased the spinal lesion size

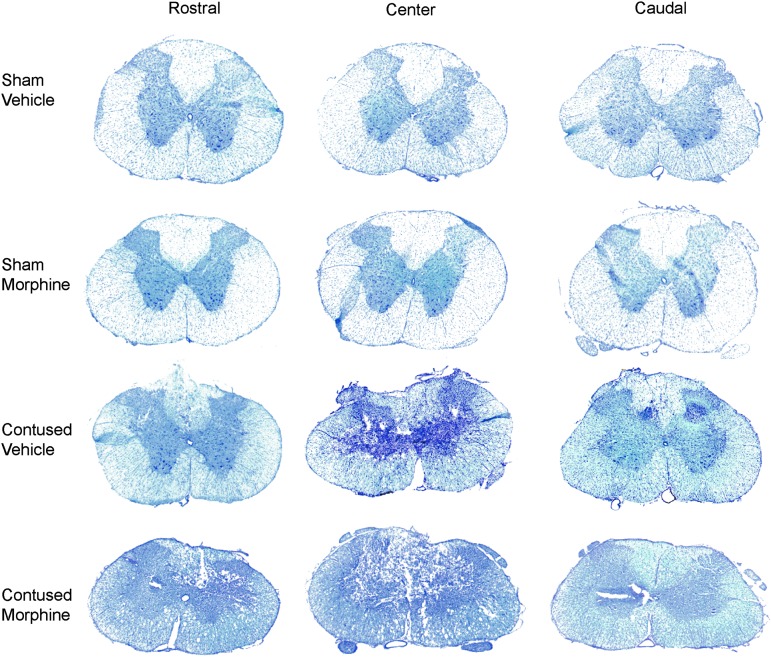

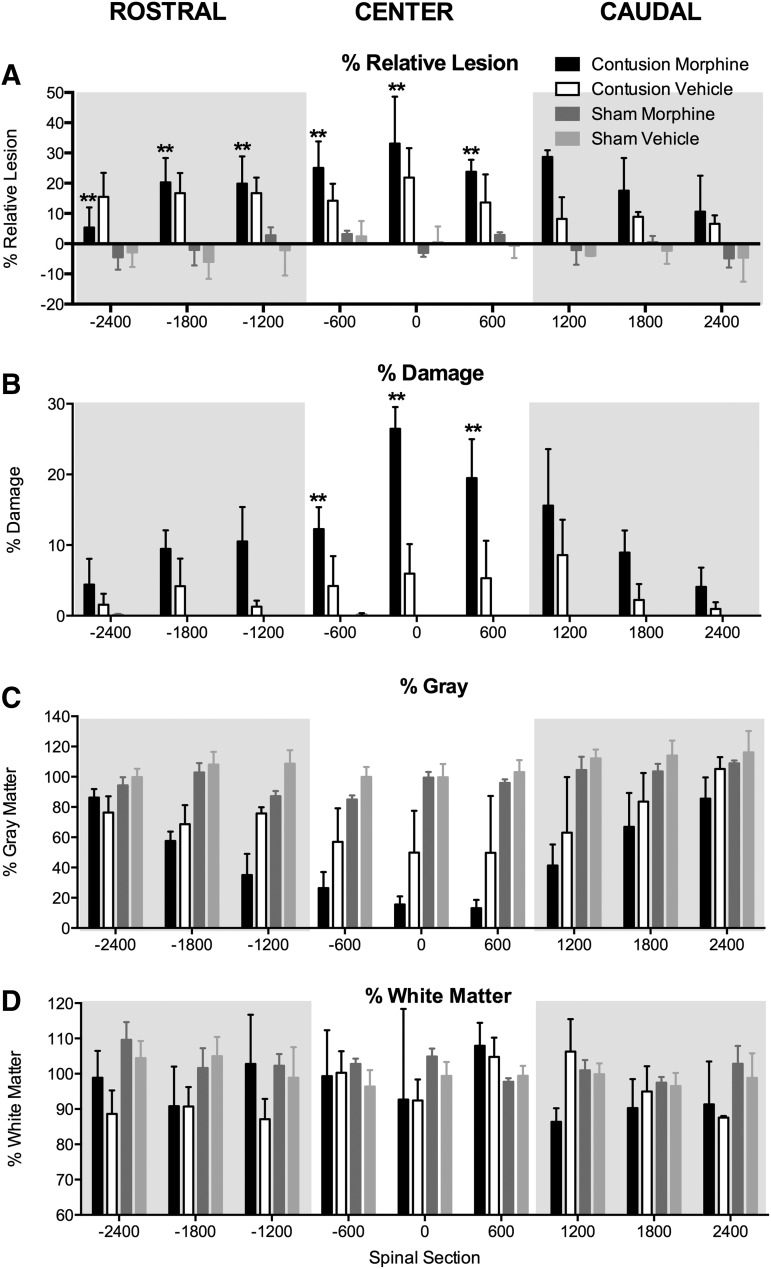

Representative spinal sections rostral, center, and caudal to the injury site are depicted for each experimental condition in Figure 4. As can be seen in Figures 4 and 5A, there was a main effect of surgery on the % relative lesion at the injury center, as well as rostral and caudal to the impact site: rostral: (F (1, 8) = 12.60, p < 0.01; center: F (1, 8) = 12.00, p < 0.01; caudal: F (1, 8) = 10.18, p < 0.05. Post hoc comparisons across groups revealed that contused subjects treated with morphine had a significantly larger % relative lesion, rostral and central to the injury site, than sham subjects treated with vehicle or morphine (p < 0.05). Although the lesion size also appears greater in contused subjects treated with vehicle, relative to shams, the statistical comparison was not significant with the small sample size (n = 3).

FIG. 4.

Representative images (4X) depicting transverse sections of the spinal cord stained with Luxol fast blue/cresyl violet. Sections rostral, center, and caudal to the injury site for each experimental condition are shown.

FIG. 5.

Morphine increased the size of the lesion induced by injury, relative to vehicle-treated spinal cord injury (SCI) and sham controls. SCI per se significantly increased the % relative lesion (A) and % damage (B), while decreasing the amount of spared gray matter (C), across the rostral-caudal extent of the lesion, relative to sham controls. There was no effect of injury on white matter sparing (D) at this early time point. Post hoc analyses indicated that subjects with SCI treated with morphine had significantly larger % relative lesion across the rostral and center spinal sections, than both sham groups. Similarly, morphine increased the % damage at the center of the lesion, relative to both the sham groups and the vehicle SCI controls. n = 3, **p < 0.05.

Commensurate with analyses for % relative lesion, there was a significant main effect of surgery on the % damage at the injury center, as well as rostral and caudal to the impact site: rostral: (F (1, 8) = 6.66, p < 0.05; center: F (1, 8) = 22.85, p < 0.05; caudal: F (1, 8) = 13.18, p < 0.05. At the center of the lesion, morphine administration further increased damage. An ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of drug condition (F (1, 8) = 7.66, p < 0.05) and significant Surgery × Drug (F (1, 8) = 7.80, p < 0.05) and Distance × Surgery interactions (F (2, 16) = 3.84, p < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons across groups revealed that at the center of the lesion, the contused subjects treated with morphine had a significantly greater area of damage than all other groups (p < 0.05, Fig. 5B). Drug treatment did not significantly impact the area of damage rostral and caudal to the injury center.

Analyses of gray and white matter sparing indicated that SCI significantly decreased the amount of gray matter remaining at the site of injury (center), as well as rostral and caudal to the injury site relative to sham subjects (Fig. 5C). There was a significant main effect of operation on the spared gray matter across the rostral-caudal extent of the lesion: center: F (1, 8) = 17.05, p < 0.05; rostral: F (1, 8) = 28.50, p < 0.05; caudal: F (1, 8) = 7.00, p < 0.05. Although there was no main effect of drug treatment across the rostral-caudal axis (F's < 3.81, p > 0.05), there were significant Distance × Surgery (F (2, 16) = 5.64, p < 0.05) and Distance × Drug interactions (F (2, 16) = 6.89, p < 0.05) in the spinal segments rostral to the site of injury. Post hoc comparisons across groups revealed that the contused subjects, irrespective of drug treatment, had significantly less gray matter spared than shams (p < 0.05). At the center of the lesion and in the caudal spinal sections, no other results approached significance (F's < 3.37, p > 0.05).

As shown in Fig. 5D, at eight days post-injury, there was no effect of contusion injury or morphine administration on the percentage of white matter spared (all F's [rostral, center, and caudal] <2.90, p's > 0.05). This is expected as cell loss and cavitation progress from the gray matter outward toward the white matter with time.47

The amount of missing tissue was also assessed. Missing tissue accounts for tissue lost as a result of factors such as atrophy, necrosis, or apoptosis that are not accounted for in analyses of lesion area alone.7 At this early time point post-injury, there was not a significant amount of missing tissue in any of the groups (all F's < 4.86, p's > 0.05).

Morphine decreased the expression of neuron, microglia, and astrocyte-specific markers

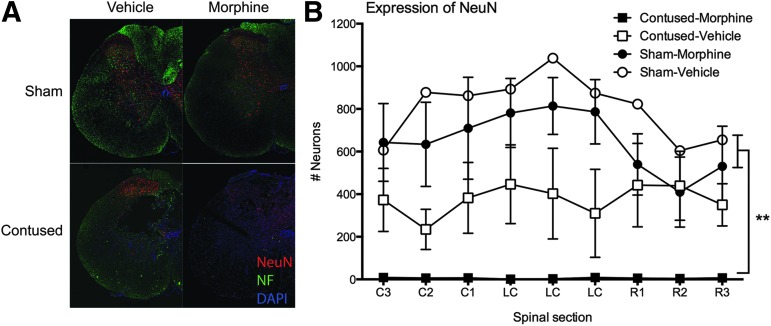

As can be seen in Fig. 6A, SCI per se decreased NeuN and neurofilament expression relative to shams (at eight days post-SCI). When morphine was administered intravenously for seven days post-injury, however, virtually no neurons, labeled with NeuN, remained across the rostral-caudal extent of the lesion. There was a significant main effect of surgery on NeuN expression at the center (F [1,8] = 19.05, p < 0.005) and rostral (F [1,8] = 12.35, p < 0.01) to the injury. The effects of surgery on NeuN loss caudal to the injury site approached significance (F [1,8] = 5.07, p = 0.055). Although there were no main effects of drug, or Surgery × Drug interactions, the effects of the operation was primarily driven by the subjects with SCI treated with morphine (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Representative images (4X), depicting NeuN and NF expression in one-half of a spinal section, at the center of the lesion, are shown for each treatment group (A). Sham subjects are shown in the upper images, and contused subjects in the lower panels. The subjects depicted in the panels on the left were treated with vehicle for seven days and those on the right were treated with seven days of intravenous morphine. The contusion injury significantly decreased NeuN and NF expression at the center of the lesion, but when morphine was administered to the subjects with spinal cord injury (SCI) for seven days, there were virtually no neurons remaining at the injury site. There was a significant effect of SCI on NeuN expression at the center and rostral to the injury site, with less NeuN expression in the contused subjects (B). Morphine-treated subjects with SCI had significantly less NeuN expression, at the center and rostral to the injury site, than both sham control groups. n = 3, **p < 0.05.

Post hoc group comparisons indicated that SCI subjects treated with morphine had significantly less NeuN expression than sham subjects treated with vehicle or morphine at the center of the lesion, and less than sham subjects treated with vehicle rostral to the injury site (p < 0.05). SCI alone also reduced NeuN expression, but the comparisons with sham subjects were not statistically significant.

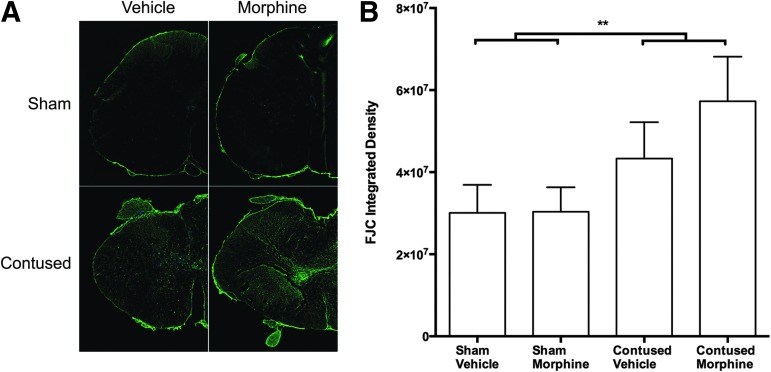

Supporting these findings, there was a main effect of surgery on Fluoro-Jade C expression at the center of the injury (F [1, 8] = 6.25, p < 0.05), but no effect of drug. As depicted in Figure 7, injury increased Fluoro-Jade C expression, with the most robust expression observed in the morphine-treated subjects. Fluoro-Jade C appears to be staining degenerating neuronal processes in the contused morphine subjects; presumptive proximal dorsal roots might also be compromised in this condition.

FIG. 7.

Spinal cord injury significantly increased Fluoro-Jade C (FJC) expression, relative to sham controls. The arrangement of the images (4X images taken of one-half of a spinal section at the center of the lesion) in (A) is the same as described for Figure 6. As depicted in Figure 7A, FJC expression was most expressed robustly in the contused subjects treated with morphine (lower right panel). At this time point, however, no effect of drug on the intensity of FJC expression emerged (B). n = 3, **p < 0.05.

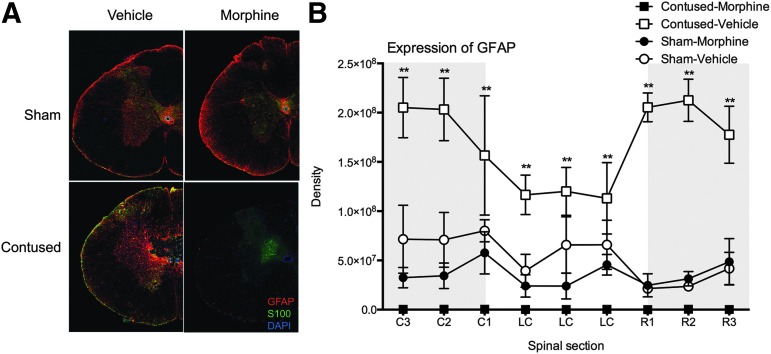

For the subjects with SCI treated with intravenous morphine, there were also no GFAP/S100-labeled astrocytes across the extent of the lesion. The absence of GFAP expression was dramatically underscored by the increased expression in subjects with SCI treated with vehicle only (Fig. 8A). As depicted in Figure 8B, there was a significant main effect of drug on GFAP expression at the injury center (F [1, 8] = 10.31, p < 0.01), and the Surgery × Drug interaction approached significance (F [1,8] = 4.19, p > 0.05). Subjects with SCI treated with morphine had significantly less GFAP expression than vehicle SCI controls (p < 0.05).

FIG. 8.

Representative images (4X) depicting glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and S-100 expression in one-half of a spinal section at the center of the lesion are shown for each treatment group (A). The arrangement of the images in Figure 8A is the same as described for Figure 6. At eight days post-injury, spinal cord injury (SCI) significantly increased GFAP expression, relative to sham controls. As can be seen in Figure 8A, however, there were virtually no astrocytes expressing GFAP or S-100 at the center of the lesion in the morphine-treated subjects with SCI. Quantifying GFAP expression, there were almost no astrocytes across the rostral-caudal extent of the lesion in morphine-treated subjects (B). Morphine-treated subjects with SCI had significantly less GFAP expression than vehicle subjects with SCI across the rostral-caudal extent of the lesion. Subjects with SCI treated with vehicle also had significantly greater GFAP expression than the sham subjects at the center of, and caudal to, the injury site. n = 3, **p < 0.05.

Similarly, rostral to the injury center, there was a main effect of drug on GFAP expression (F [1, 8] = 60.48, p < 0.001) and a Surgery × Drug interaction (F [1, 8] = 68.20, p < 0.001). Subjects with SCI treated with saline had significantly more GFAP expression than all other groups (p < 0.05). Caudal to the injury site, there was a significant main effect of drug (F [1, 8] = 14.97, p < 0.005) and a Surgery × Drug interaction (F [1, 8] = 7.43, p < 0.05). Both sham and SCI groups treated with morphine had significantly less GFAP expression than SCI vehicle subjects (p < 0.05).

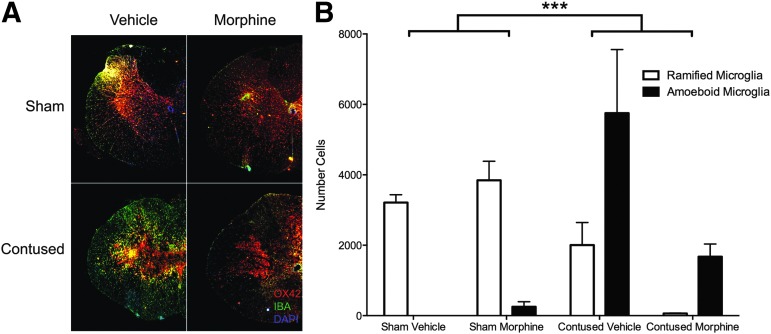

Finally, for microglia, morphine appears to substantially reduce the expression of ramified and activated OX-42 labeled microglia remaining at the injury center (Fig. 9A), relative to vehicle-treated controls, although substantial numbers of activated microglia remain. Using repeated measures ANOVAs, we found a significant Surgery × Drug interaction (F [1,8] = 6.94, p < 0.05). As can be seen in Figure 9B, this effect was primarily because of the differential expression of ramified and amoeboid microglia in the sham versus contused subjects and the decreased expression of microglia, overall, in the contused subjects treated with morphine. Individual ANOVAs revealed a significant effect of operation on the numbers of ramified microglia present (F [1,12] = 11.02, p < 0.05), and the effect of operation on amoeboid microglia approached significance (F [1,12] = 5.02, p = 0.055).

FIG. 9.

Representative images (4X) depicting OX-42 and IBA1 expression in one-half of a spinal section at the center of the lesion, are shown for each treatment group (A). The arrangement of the images in Figure 9A is the same as described for Figure 6. SCI increased the expression of amoeboid OX-42 labeled microglia and significantly decreased the expression of ramified microglia relative to sham controls (B). Although morphine-treated subjects with SCI appear to have less amoeboid microglia remaining at the injury center compared with vehicle-treated SCI controls, there was no significant difference between these groups. n = 3, **p < 0.05.

Discussion

Repeated morphine administration significantly decreased the expression of neurons and glia, relative to vehicle-treated controls, after SCI. There was a significant increase in the lesion size of morphine-treated subjects, and replicating our previous studies, we found that morphine significantly undermined recovery of locomotor function after SCI.5–8,30 Despite the loss of neurons, however, repeated morphine administration led to the development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia, with subjects displaying increased reactivity to innocuous mechanical stimulation. As suggested by Garraway and associates,29 a loss of GABAergic neurons after SCI, and morphine in the current study, may underlie this paradoxical pain hypersensitivity.

The dramatic effects of morphine on NeuN and GFAP expression are commensurate with data from other models demonstrating apoptosis with morphine administration. For example, Liu and colleagues48 reported that 14 days of IP morphine increased neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampus of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, increasing the expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins Fas and Caspase-3 while decreasing anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 expression. Similarly, Emeterio and coworkers49 found that chronic morphine-treated mice exhibited scattered apoptotic neurons throughout the brain. This neurotoxic effect was accompanied by up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic proteins FasL, Fas, and Bad and the active fragments of Caspase-8 and Caspase-3 in cortical and hippocampal lysates. Atici and colleagues50 showed that chronic IP morphine and tramadol increased neuronal apoptosis in the temporal and occipital regions of the brain of adult rats. These documented neurotoxic effects of morphine may explain the decreased expression of NeuN in the present study. Moreover, the apoptotic effects of morphine are not limited to neurons. Morphine-induced cell death has also been reported for neuroprogenitor cells,51 T cells,52 microglia,53 macrophages,54 and astrocytes.49,55

As noted above, some studies suggest that morphine induces cell death by increasing FasL expression and activating downstream targets of the Fas receptor, including Caspases-3 and 8. This increased FasL expression appears to depend on morphine binding to opioid receptors on the immune cells, as it is blocked by naloxone.56 In the SCI model, increased FasL expression of microglia and infiltrating immune cells may prime the system to undergo Fas-mediated apoptosis. Indeed, our preliminary data suggest that minocycline blocks the effects of morphine on the recovery of locomotor function (Aceves and associates, unpublished data).

Alternatively, morphine binding to opioid receptors on immune cells may increase the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the injured mileau of the spinal cord, and thereby promote both astrocyte and neuronal death.57,58 We have shown that both IT and IP morphine significantly increase spinal IL-1β expression levels.7 Others have also implicated pro-inflammatory cytokines in glutamate-receptor trafficking and excitotoxicity after SCI.27,59 Opioid-immune interactions may mediate cell death when morphine is superimposed on the injured spinal cord.

Morphine may potentiate cell death by binding to classic or non-classic opioid receptors. We have shown that activation of the κ-opioid receptor is both necessary and sufficient for the morphine-induced attenuation of locomotor function after SCI. Aceves and associates60 found that a single administration of GR89696, a selective κ2-opioid receptor agonist, undermines locomotor recovery after SCI, even when the dose administered was 32-fold less than the 90 μg dose of IT morphine. Further, administration of nor-Binaltorphimine before morphine blocked the adverse effects of the opioid on locomotor recovery (Aceves and associates, unpublished data).

We hypothesize that morphine binding to κ-opioid receptors on microglia or infiltrating immune cells61–64 may increase the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and thereby exacerbate neurotoxicity. Similarly, although a single administration of DAMGO, a selective μ-opioid receptor agonist, was not sufficient to undermine recovery of locomotor function after SCI,60 repeated administrations may lead to excitotoxicity. As discussed for the κ-opioid receptors, activation of the μ-opioid receptor on glial cells may produce neurotoxicity through increased pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Activation of non-classic opioid receptors, such as TLR4 on microglia and activated astrocytes, also activates NF-κB resulting in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β and TNFα), and leading to the activation of Caspase-3. As found for DAMGO, however, neither lipopolysaccharide nor the stereoselective enantiomer of morphine, [+]- morphine, was sufficient to reduce locomotor recovery in our studies.60

Alternatively, the repeated activation of μ-opioid receptors on neurons may initiate a G-protein mediated protein kinase C (PKC) translocation and activation, promoting the removal of the NMDA receptor Mg2+ plug15 and allowing Ca2+ influx.

Yang and colleagues65,66 have also shown that chronic morphine exposure is associated with post-transcriptional down regulation of the glutamate transporter, EAAC1, directly contributing to the heightened activity of NMDA receptors. Overall, sustained potentiation of the NMDA receptor maintains central sensitization and hyperalgesia in the neural system and may lead to excitotoxic cell death.10,67

Further studies are necessary to determine the molecular pathways underlying the decreased expression of neuronal and glial markers after SCI and morphine administration. Deriving the mechanism underlying the morphine-induced cell loss after SCI will be critical for the development of safe and effective pain management strategies.

In addition to adverse effects on locomotor function, we found that chronic morphine exposure produced increased symptoms of pain, with opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia was particularly evident in the sham rats, but was also clear after SCI on the measure of tactile reactivity. These data are commensurate with other animal17,68–73 and clinical studies demonstrating that both tolerance and hyperalgesia are commonly encountered among patients using opioids to control pain.41,74–80

While the behavioral effects of repeated opioid administration on hyperalgesia and tolerance are clear, the molecular changes that might mediate these effects are not. In previous studies, tolerance has been linked to activation of TLR4 on glia and the release of IL-1β, which has been shown to oppose the analgesic properties of morphine.18 Glia are also involved in the development and maintenance of increased pain reactivity and neuropathic pain after SCI.14,81–85 Indeed, pre-treatment with an IL-1 receptor antagonist prevented increases in morphine-induced at-level neuropathic pain symptoms in our contusion model.7

In the current study, however, despite decreased glial expression, the morphine-treated subjects displayed increased pain reactivity. We propose that morphine and SCI may synergistically increase the loss of GABAergic neurons potentiating the development of pain symptoms. A loss of GABAergic inhibitory tone has been associated with the development of neuropathic pain symptoms in models of contusion and excitotoxic SCI, as well as peripheral nerve injury.83,86–88 Morphine-induced cell death may not only underlie the decreases in recovery seen in our studies, it may also contribute to the development of long-term pain.

Conclusion

Morphine administration in the acute phase of a rodent SCI decreases recovery of locomotor function, increases pain reactivity, and significantly increases cell loss at the lesion site. It is also likely that the effects of IV morphine extend beyond these spinally mediated behaviors. As noted previously, a number of studies have documented supraspinal neuronal death with IP morphine administration.48,49 Based on these data, it is tempting to suggest that opioid analgesics be withheld during the early stage of SCI. As noted previously, however, inadequate treatment of pain is not only unethical but may also predispose patients to the development of long-term chronic pain.

With few alternatives, we are not in the position to potentiate the risk of long-term pain and discard one of our most effective classes of analgesics. We must refine our therapeutic strategies, however, to target critical molecular changes and reduce the potential for adverse effects with pharmaceutical intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant DA31197 to M.A. Hook. The NIDA Drug Supply Program generously provided morphine sulfate. We would also like to thank Alejandro R. Aceves, Kiralyn Brakel, and Mabel Terminel for their comments on a previous version of this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. (2008). Early acute management in adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J. Spinal Cord Med. 31, 403–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neighbor M.L., Honner S., and Kohn M.A. (2004). Factors affecting emergency department opioid administration to severely injured patients. Acad. Emerg. Med. 11, 1290–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz J., and Seltzer Z. (2009). Transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: risk factors and protective factors. Expert Rev. Neurother. 9, 723–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyranou M., and Puntillo K. (2012). The transition from acute to chronic pain: might intensive care unit patients be at risk? Ann. Intensive Care 2, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hook M.A., Liu G.T., Washburn S.N., Ferguson A.R., Bopp A.C., Huie J.R., and Grau J.W. (2007). The impact of morphine after a spinal cord injury. Behav. Brain Res. 179, 281–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hook M.A., Moreno G., Woller S., Puga D., Hoy K., Jr., Balden R., and Grau J.W. (2009). Intrathecal morphine attenuates recovery of function after a spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 26, 741–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hook M.A., Washburn S.N., Moreno G., Woller S.A., Puga D., Lee K.H., and Grau J.W. (2011). An IL-1 receptor antagonist blocks a morphine-induced attenuation of locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury. Brain Behav. Immun. 25, 349–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woller S.A., Moreno G.L., Hart N., Wellman P.J., Grau J.W., and Hook M.A. (2012). Analgesia or addiction?: implications for morphine use after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 29, 1650–1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woller S.A., and Hook M.A. (2013). Opioid administration following spinal cord injury: implications for pain and locomotor recovery. Exp. Neurol. 247, 328–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao J., Sung B., Ji R.R., and Lim G. (2002). Neuronal apoptosis associated with morphine tolerance: evidence for an opioid-induced neurotoxic mechanism. J. Neurosci. 22, 7650–7661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ram K.C., Eisenberg E., Haddad M., and Pud D. (2008). Oral opioid use alters DNIC but not cold pain perception in patients with chronic pain—new perspective of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain 139, 431–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King T., Ossipov M.H., Vanderah T.W., Porreca F., and Lai J. (2005). Is paradoxical pain induced by sustained opioid exposure an underlying mechanism of opioid antinociceptive tolerance? Neurosignals 14, 194–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ossipov M.H., Lai J., King T., Vanderah T.W., and Porreca F. (2005). Underlying mechanisms of pronociceptive consequences of prolonged morphine exposure. Biopolymers 80, 319–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwak Y.S., Kang J., Unabia G.C., and Hulsebosch C.E. (2012). Spatial and temporal activation of spinal glial cells: role of gliopathy in central neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury in rats. Exp. Neurol. 234, 362–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L., and Huang L.Y. (1992). Protein kinase C reduces Mg2+ block of NMDA-receptor channels as a mechanism of modulation. Nature 356, 521–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woolf C.J., and Salter M.W. (2000). Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science 288, 1765–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao J., Price D.D., Phillips L.L., Lu J., and Mayer D.J. (1995). Increases in protein kinase C gamma immunoreactivity in the spinal cord of rats associated with tolerance to the analgesic effects of morphine. Brain Res. 677, 257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchinson M.R., Shavit Y., Grace P.M., Rice K.C., Maier S.F., and Watkins L.R. (2011). Exploring the neuroimmunopharmacology of opioids: an integrative review of mechanisms of central immune signaling and their implications for opioid analgesia. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 772–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim G., Wang S., Zeng Q., Sung B., Yang L., and Mao J. (2005). Expression of spinal NMDA receptor and PKCgamma after chronic morphine is regulated by spinal glucocorticoid receptor. J. Neurosci. 25, 11145–11154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLeo J.A., and Yezierski R.P. (2001). The role of neuroinflammation and neuroimmune activation in persistent pain. Pain 90, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watkins L.R., Milligan E.D., and Maier S.F. (2001). Spinal cord glia: new players in pain. Pain 93, 201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watkins L.R., Milligan E.D., and Maier S.F. (2001). Glial activation: a driving force for pathological pain. Trends Neurosci. 24, 450–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston I.N., Milligan E.D., Wieseler-Frank J., Frank M.G., Zapata V., Campisi J., Langer S., Martin D., Green P., Fleshner M., Leinwand L., Maier S.F. and Watkins L.R. (2004). A role for proinflammatory cytokines and fractalkine in analgesia, tolerance, and subsequent pain facilitation induced by chronic intrathecal morphine. J. Neurosci. 24, 7353–7365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White F.A., Jung H., and Miller R.J. (2007). Chemokines and the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 20151–20158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scholz J., and Woolf C.J. (2007). The neuropathic pain triad: neurons, immune cells and glia. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1361–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nesic O., Xu G.Y., McAdoo D., High K.W., Hulsebosch C., and Perez-Pol R. (2001). IL-1 receptor antagonist prevents apoptosis and caspase-3 activation after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 18, 947–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson A.R., Christensen R.N., Gensel J.C., Miller B.A., Sun F., Beattie E.C., Bresnahan J.C., and Beattie M.S. (2008). Cell death after spinal cord injury is exacerbated by rapid TNF alpha-induced trafficking of GluR2-lacking AMPARs to the plasma membrane. J. Neurosci. 28, 11391–11400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin H.Z., Hsu C.I., Yu S., Rao S.D., Sorkin L.S., and Weiss J.H. (2012). TNF-alpha triggers rapid membrane insertion of Ca(2+) permeable AMPA receptors into adult motor neurons and enhances their susceptibility to slow excitotoxic injury. Exp. Neurol. 238, 93–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garraway S.M., Woller S.A., Huie J.R., Hartman J.J., Hook M.A., Miranda R.C., Huang Y.J., Ferguson A.R., and Grau J.W. (2014). Peripheral noxious stimulation reduces withdrawal threshold to mechanical stimuli after spinal cord injury: role of tumor necrosis factor alpha and apoptosis. Pain 155, 2344–2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woller S.A., Malik J.S., Aceves M., and Hook M.A. (2014). Morphine self-administration following spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 31, 1570–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wishart D.S., Knox C., Guo A.C., Shrivastava S., Hassanali M., Stothard P., Chang Z., and Woolsey J. (2006). DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D668–D672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwamoto K., and Klaassen C.D. (1977). First-pass effect of morphine in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 200, 236–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharasch E.D., Hoffer C., Whittington D., and Sheffels P. (2003). Role of P-glycoprotein in the intestinal absorption and clinical effects of morphine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 74, 543–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bengtsson J., Ederoth P., Ley D., Hansson S., Amer-Wahlin I., Hellstrom-Westas L., Marsal K., Nordstrom C.H., and Hammarlund-Udenaes M. (2009). The influence of age on the distribution of morphine and morphine-3-glucuronide across the blood-brain barrier in sheep. Br. J. Pharmacol. 157, 1085–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadiq M.W., Salehpour M., Forsgard N., Possnert G., and Hammarlund-Udenaes M. (2011). Morphine brain pharmacokinetics at very low concentrations studied with accelerator mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Drug Metab. Dispos. 39, 174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meissner K., Avram M.J., Yermolenka V., Francis A.M., Blood J., and Kharasch E.D. (2013). Cyclosporine-inhibitable blood-brain barrier drug transport influences clinical morphine pharmacodynamics. Anesthesiology 119, 941–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dulin J.N., Moore M.L., and Grill R.J. (2013). The dual cyclooxygenase/5-lipoxygenase inhibitor licofelone attenuates p-glycoprotein-mediated drug resistance in the injured spinal cord. J. Neurotrauma 30, 211–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coffman B.L., Rios G.R., King C.D., and Tephly T.R. (1997). Human UGT2B7 catalyzes morphine glucuronidation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 25, 1–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King C., Tang W., Ngui J., Tephly T., and Braun M. (2001). Characterization of rat and human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases responsible for the in vitro glucuronidation of diclofenac. Toxicol. Sci. 61, 49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angst M.S., and Clark J.D. (2006). Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology 104, 570–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L., Sein M., Vo T., Amhmed S., Zhang Y., Hilaire K.S., Houghton M., and Mao J. (2014). Clinical interpretation of opioid tolerance versus opioid-induced hyperalgesia. J. Opioid Manag. 10, 383–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basso D.M., Beattie M.S., and Bresnahan J.C. (1995). A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J. Neurotrauma 12, 1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beattie M.S. (1992). Anatomic and behavioral outcome after spinal cord injury produced by a displacement controlled impact device. J. Neurotrauma 9, 157–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Behrmann D.L., Bresnahan J.C., Beattie M.S., and Shah B.R. (1992). Spinal cord injury produced by consistent mechanical displacement of the cord in rats: behavioral and histologic analysis. J. Neurotrauma 9, 197–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grau J.W., Washburn S.N., Hook M.A., Ferguson A.R., Crown E.D., Garcia G., Bolding K.A., and Miranda R.C. (2004). Uncontrollable stimulation undermines recovery after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 21, 1795–1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferguson A.R., Hook M.A., Garcia G., Bresnahan J.C., Beattie M.S., and Grau J.W. (2004). A simple post hoc transformation that improves the metric properties of the BBB scale for rats with moderate to severe spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 21, 1601–1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.James N.D., Bartus K., Grist J., Bennett D.L., McMahon S.B., and Bradbury E.J. (2011). Conduction failure following spinal cord injury: functional and anatomical changes from acute to chronic stages. J. Neurosci. 31, 18543–18555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu L.W., Lu J., Wang X.H., Fu S.K., Li Q., and Lin F.Q. (2013). Neuronal apoptosis in morphine addiction and its molecular mechanism. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 6, 540–545 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emeterio E.P., Tramullas M., and Hurle M.A. (2006). Modulation of apoptosis in the mouse brain after morphine treatments and morphine withdrawal. J. Neurosci. Res. 83, 1352–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atici S., Cinel L., Cinel I., Doruk N., Aktekin M., Akca A., Camdeviren H., and Oral U. (2004). Opioid neurotoxicity: comparison of morphine and tramadol in an experimental rat model. Int. J. Neurosci. 114, 1001–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willner D., Cohen-Yeshurun A., Avidan A., Ozersky V., Shohami E., and Leker R.R. (2014). Short term morphine exposure in vitro alters proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells and promotes apoptosis via mu receptors. PLoS One 9, e103043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chandel N., Sharma B., Salhan D., Husain M., Malhotra A., Buch S., and Singhal P.C. (2012). Vitamin D receptor activation and downregulation of renin-angiotensin system attenuate morphine-induced T cell apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 303, C607–C615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He L., Li H., Chen L., Miao J., Jiang Y., Zhang Y., Xiao Z., Hanley G., Li Y., Zhang X., LeSage G., Peng Y., and Yin D. (2011). Toll-like receptor 9 is required for opioid-induced microglia apoptosis. PLoS One 6, e18190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhat R.S., Bhaskaran M., Mongia A., Hitosugi N., and Singhal P.C. (2004). Morphine-induced macrophage apoptosis: oxidative stress and strategies for modulation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75, 1131–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deb I., and Das S. (2011). Thyroid hormones protect astrocytes from morphine-induced apoptosis by regulating nitric oxide and pERK 1/2 pathways. Neurochem. Int. 58, 861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yin D., Mufson R.A., Wang R., and Shi Y. (1999). Fas-mediated cell death promoted by opioids. Nature 397, 218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Kralingen C., Kho D.T., Costa J., Angel C.E., and Graham E.S. (2013). Exposure to inflammatory cytokines IL-1beta and TNFalpha induces compromise and death of astrocytes; implications for chronic neuroinflammation. PLoS One 8, e84269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ye L., Huang Y., Zhao L., Li Y., Sun L., Zhou Y., Qian G., and Zheng J.C. (2013). IL-1beta and TNF-alpha induce neurotoxicity through glutamate production: a potential role for neuronal glutaminase. J. Neurochem. 125, 897–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hermann G.E., Rogers R.C., Bresnahan J.C., and Beattie M.S. (2001). Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces cFOS and strongly potentiates glutamate-mediated cell death in the rat spinal cord. Neurobiol. Dis. 8, 590–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aceves M., Mathai B.B., and Hook M.A. (2016). Evaluation of the effects of specific opioid receptor agonists in a rodent model of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 54, 757–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang A.C., Chao C.C., Takemori A.E., Gekker G., Hu S., Peterson P.K., and Portoghese P.S. (1996). Arylacetamide-derived fluorescent probes: synthesis, biological evaluation, and direct fluorescent labeling of kappa opioid receptors in mouse microglial cells. J. Med. Chem. 39, 1729–1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chao C.C., Gekker G., Hu S., Sheng W.S., Shark K.B., Bu D.F., Archer S., Bidlack J.M. and Peterson P.K. (1996). Kappa opioid receptors in human microglia downregulate human immunodeficiency virus 1 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 8051–8056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karaji A.G., Reiss D., Matifas A., Kieffer B.L., and Gaveriaux-Ruff C. (2011). Influence of endogenous opioid systems on T lymphocytes as assessed by the knockout of mu, delta and kappa opioid receptors. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 6, 608–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gabrilovac J., Cupic B., Zapletal E., and Brozovic A. (2012). IFN-gamma up-regulates kappa opioid receptors (KOR) on murine macrophage cell line J774. J Neuroimmunol. 245, 56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang L., Wang S., Lim G., Sung B., Zeng Q., and Mao J. (2008). Inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome activity prevents glutamate transporter degradation and morphine tolerance. Pain 140, 472–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang L., Wang S., Sung B., Lim G., and Mao J. (2008). Morphine induces ubiquitin-proteasome activity and glutamate transporter degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21703–21713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mayer D.J., Mao J., Holt J. and Price D.D. (1999). Cellular mechanisms of neuropathic pain, morphine tolerance, and their interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 7731–7736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hutchinson M.R., Lewis S.S., Coats B.D., Rezvani N., Zhang Y., Wieseler J.L., Somogyi A.A., Yin H., Maier S.F., Rice K.C., and Watkins L.R. (2010). Possible involvement of toll-like receptor 4/myeloid differentiation factor-2 activity of opioid inactive isomers causes spinal proinflammation and related behavioral consequences. Neuroscience 167, 880–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mattioli T.A., Leduc-Pessah H., Skelhorne-Gross G., Nicol C.J., Milne B., Trang T., and Cahill C.M. (2014). Toll-like receptor 4 mutant and null mice retain morphine-induced tolerance, hyperalgesia, and physical dependence. PLoS One 9, e97361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Celerier E., Laulin J.P., Corcuff J.B., Le Moal M., and Simonnet G. (2001). Progressive enhancement of delayed hyperalgesia induced by repeated heroin administration: a sensitization process. J. Neurosci. 21, 4074–4080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Celerier E., Rivat C., Jun Y., Laulin J.P., Larcher A., Reynier P., and Simonnet G. (2000). Long-lasting hyperalgesia induced by fentanyl in rats: preventive effect of ketamine. Anesthesiology 92, 465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laboureyras E., Aubrun F., Monsaingeon M., Corcuff J.B., Laulin J.P., and Simonnet G. (2014). Exogenous and endogenous opioid-induced pain hypersensitivity in different rat strains. Pain Res. Manag. 19, 191–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wala E.P., and Holtman J.R., Jr. (2011). Buprenorphine-induced hyperalgesia in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 651, 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chu L.F., Clark D.J., and Angst M.S. (2006). Opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia in chronic pain patients after one month of oral morphine therapy: a preliminary prospective study. J. Pain 7, 43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chu L.F., D'Arcy N., Brady C., Zamora A.K., Young C.A., Kim J.E., Clemenson A.M., Angst M.S. and Clark J.D. (2012). Analgesic tolerance without demonstrable opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of sustained-release morphine for treatment of chronic nonradicular low-back pain. Pain 153, 1583–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Compton P., Athanasos P., and Elashoff D. (2003). Withdrawal hyperalgesia after acute opioid physical dependence in nonaddicted humans: a preliminary study. J. Pain 4, 511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Compton P., Charuvastra V.C. and Ling W. (2001). Pain intolerance in opioid-maintained former opiate addicts: effect of long-acting maintenance agent. Drug Alcohol Depend. 63, 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hay J.L., White J.M., Bochner F., Somogyi A.A., Semple T.J., and Rounsefell B. (2009). Hyperalgesia in opioid-managed chronic pain and opioid-dependent patients. J Pain 10, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Angst M.S., Koppert W., Pahl I., Clark D.J., and Schmelz M. (2003). Short-term infusion of the mu-opioid agonist remifentanil in humans causes hyperalgesia during withdrawal. Pain 106, 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koppert W., Sittl R., Scheuber K., Alsheimer M., Schmelz M., and Schuttler J. (2003). Differential modulation of remifentanil-induced analgesia and postinfusion hyperalgesia by S-ketamine and clonidine in humans. Anesthesiology 99, 152–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hains B.C., and Waxman S.G. (2006). Activated microglia contribute to the maintenance of chronic pain after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 26, 4308–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crown E.D., Gwak Y.S., Ye Z., Johnson K.M., and Hulsebosch C.E. (2008). Activation of p38 MAP kinase is involved in central neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 213, 257–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gwak Y.S., Crown E.D., Unabia G.C., and Hulsebosch C.E. (2008). Propentofylline attenuates allodynia, glial activation and modulates GABAergic tone after spinal cord injury in the rat. Pain 138, 410–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gwak Y.S., and Hulsebosch C.E. (2009). Remote astrocytic and microglial activation modulates neuronal hyperexcitability and below-level neuropathic pain after spinal injury in rat. Neuroscience 161, 895–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carlton S.M., Du J., Tan H.Y., Nesic O., Hargett G.L., Bopp A.C., Yamani A., Lin Q., Willis W.D., and Hulsebosch C.E. (2009). Peripheral and central sensitization in remote spinal cord regions contribute to central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain 147, 265–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gwak Y.S., Tan H.Y., Nam T.S., Paik K.S., Hulsebosch C.E., and Leem J.W. (2006). Activation of spinal GABA receptors attenuates chronic central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 23, 1111–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eaton M.J., and Wolfe S.Q. (2009). Clinical feasibility for cell therapy using human neuronal cell line to treat neuropathic behavioral hypersensitivity following spinal cord injury in rats. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 46, 145–165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vaysse L., Sol J.C., Lazorthes Y., Courtade-Saidi M., Eaton M.J., and Jozan S. (2011). GABAergic pathway in a rat model of chronic neuropathic pain: modulation after intrathecal transplantation of a human neuronal cell line. Neurosci. Res. 69, 111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]