Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the number one cause of disability worldwide and is comorbid with many chronic diseases, including obesity/metabolic syndrome (MetS). Women have twice as much risk for MDD and comorbidity with obesity/MetS as men, although pathways for understanding this association remain unclear. On the basis of clinical and preclinical studies, we argue that prenatal maternal stress (ie, excess glucocorticoid expression and associated immune responses) that occurs during the sexual differentiation of the fetal brain has sex-dependent effects on brain development within highly sexually dimorphic regions that regulate mood, stress, metabolic function, the autonomic nervous system, and the vasculature. Furthermore, these effects have lifelong consequences for shared sex-dependent risk of MDD and obesity/MetS. Thus, we propose that there are shared biologic substrates at the anatomical, molecular, and/or genetic levels that produce the comorbid risk for MDD-MetS through sex-dependent fetal origins.

Keywords: depression, depression-cardiometabolic comorbidity, fetal programming, inflammation, obesity/metabolic syndrome, prenatal stress model, sex difference

Abstract

El trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM) es la causa número uno de incapacidad en el mundo y es comórbido con muchas enfermedades crónicas, incluyendo la obesidad y el síndrome metabólico (SMet). Si bien las mujeres tienen el doble de riesgo que los hombres para el TDM y para la comorbilidad con obesidad y SMet, aun no se han aclarado las bases para comprender esta asociación. En base a estudios clínicos y preclínicos, se argumenta que el estrés materno prenatal (como la expresión excesiva de glucocorticoides y las respuestas inmunes asociadas) que ocurre durante la diferenciación sexual del cerebro fetal tiene efectos dependientes del sexo sobre el desarrollo cerebral en las regiones con alto dimorfismo sexual que regulan el ánimo, el estrés, la función metabólica, el sistema nervioso autónomo y la vascularización. Además, estos efectos tienen consecuencias a lo largo de la vida para el riesgo compartido sexo-dependiente para TDM y obesidad/SMet. Por lo tanto, se propone que hay sustratos biológicos compartidos a niveles anatómicos, moleculares y/o genéticos que producirían el riesgo comórbido para el TDM-SMet a través de orígenes fetales sexo-dependientes.

Abstract

Le trouble dépressif caractérisé (TDC) est la première cause d'invalidité dans le monde et il existe une comorbidité avec de nombreuses maladies chroniques, dont le syndrome métabolique/obésité (SMet). Le risque de TDC est deux fois plus élevé chez les femmes ayant un SMet que chez les hommes, mais les tenants et les aboutissants de cette association sont encore mal compris. Au vu des études cliniques et précliniques existantes, nous soutenons que le stress maternel prénatal (c'est-à-dire l'excès de libération de glucocorticoïdes et les réponses immunes associées) qui survient pendant la différentiation sexuelle du cerveau du foetus a des effets dépendant du sexe sur le développement cérébral dans des régions très dimorphiques sexuellement, régulant l'humeur, le stress, la fonction métabolique, le système nerveux autonome et la vascularisation. De plus, les conséquences de ces effets pour le risque partagé de TDC et de SMet/obésité en fonction du sexe durent toute la vie. Nous pensons donc qu'il existerait des substrats biologiques partagés aux niveaux anatomique, moléculaire et/ou génétique qui seraient responsables du risque comorbide de TDC-SMet selon le sexe du foetus.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the number one cause of disability worldwide, with women having twice the risk of men.1 Furthermore, depression is comorbid with other chronic medical conditions, including obesity and metabolic syndrome (MetS),2 with higher prevalence of the comorbidity among women. MDD is more severe among comorbid obese than nonobese depressed individuals, with poorer weight loss outcomes and increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). The comorbidity of MDD and obesity/MetS contributes substantially to increased medical expenditures, reaching about $245 billion in the United States alone3 and is associated with premature death.

A number of studies demonstrated fetal risk factors for MDD4-6 and obesity/MetS,7 with final common pathways involving disruption of maternal-fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis development (ie, “prenatal stress” models of chronic disease). The conceptualization of prenatal stress includes obstetric conditions (eg, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction), maternal overnutrition or undernutrition, and other environmental and psychological exposures that cause maternal secretion of glucocorticoids and subsequent immune dysregulation. The pathways through which these stressors impact fetal growth and brain development are not well understood, but probably involve genetic and epigenetic mechanisms mediated by hormones, growth factors, and/or markers of immune function that cross the placenta.

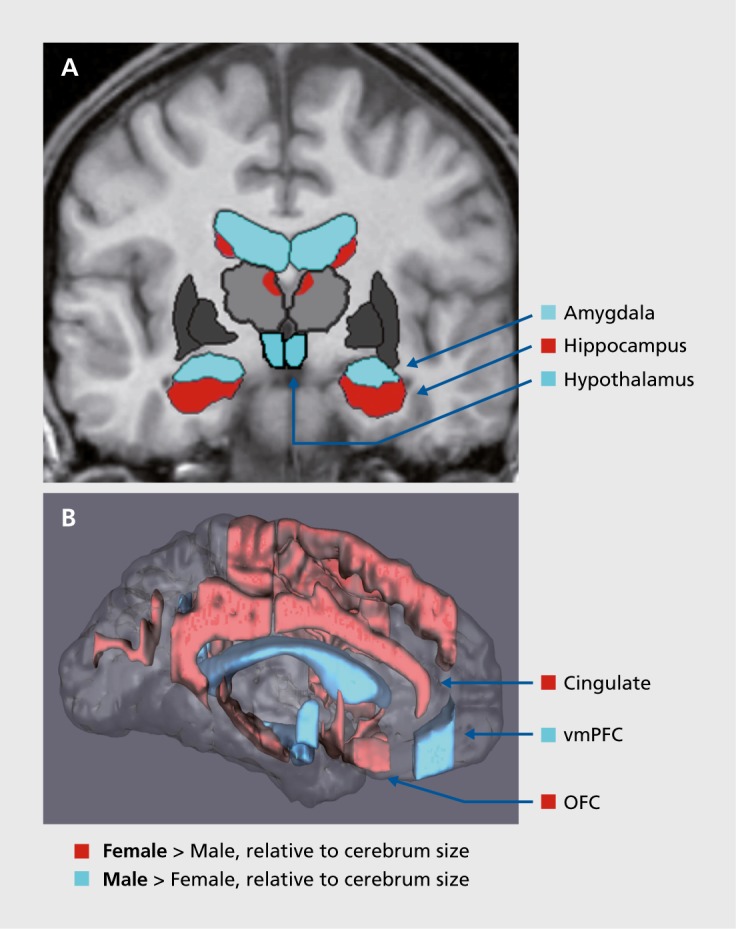

We argue that prenatal stress disruptions occurring during key gestational periods have sex-dependent effects on brain development within highly sexually dimorphic regions that regulate mood, stress, metabolic function, the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and others. Brain regions implicated in mood, ANS, metabolism, and CVD function include the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), central/medial amygdala, hippocampus, periaqueductal gray, medial and orbital prefrontal cortices, and anterior cingulate cortex. These brain regions are morphologically and functionally sexually dimorphic8-12 (Figure 1).Thus, as shown in clinical and preclinical studies, prenatal maternal stress (ie, excess glucocorticoid expression and associated immune disruption) that occurs during the sexual differentiation of the fetal brain will produce lifelong, shared risk for sex differences in MDD-MetS by altering the development of common pathways. Previous critical reviews by our team argued this case for MDD-CVD.13,14

Figure 1. Sexually dimorphic subcortical (A) and cortical (B) regions in stress and mood circuitries. Shared neural circuitry implicated in mood, stress, metabolic function, and the autonomic nervous system, highlighting regions with relatively dense distribution of gonadal and/or adrenal hormone receptors. In women, regions larger in volume relative to cerebrum size include orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and hippocampus, whereas in men, regions larger relative to cerebrum size include amygdala and hypothalamus. OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; vmPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Based on reference 11: Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Horton NJ, et al. Normal sexual dimorphism of the adult human brain assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11(6):490-497.

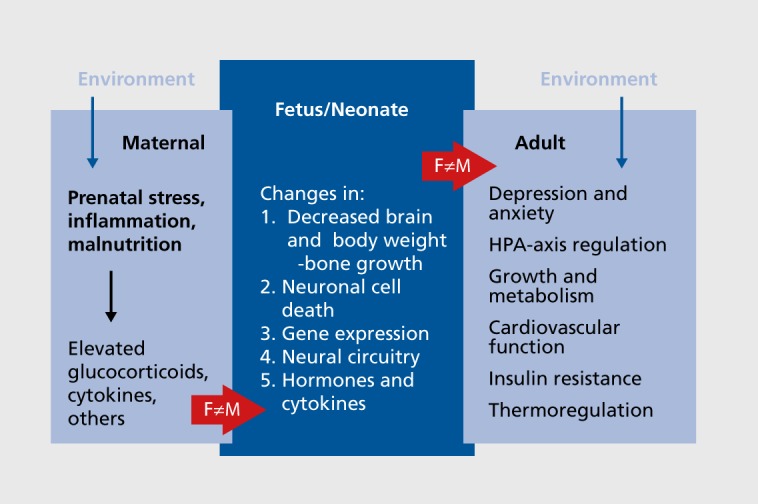

We believe there are shared biologic substrates at the anatomical, molecular, and/or genetic levels that produce comorbid risk for these disorders that have fetal origins and are sex-dependent (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fetal antecedents to sex differences in comorbidity of depression and metabolic syndrome. This figure illustrates a prenatal stress-immune model of sex differences in the comorbidity of depression and metabolic syndrome emphasizing maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis dysregulation (elevated glucocorticoids and proinflammatory expression) during gestation that impacts development of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal circuitry in the fetus in sex-dependent ways, with lifelong consequences for mood/anxiety, the endocrine and autonomic nervous systems, growth and metabolism, vascular structure and function, and insulin resistance. F, female; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; M, male.

Clinical evidence

Epidemiology

In 2012, MDD became the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, surpassing ischemic heart disease, with almost 20% prevalence in women. Similarly, rates of adult obesity increased dramatically between 1999 and 2004 and reached 41% in 2015.3 More women suffer from comorbidities with MDD than men, with women being 62% more likely to have multiple conditions. Although men have higher rates of comorbid CVD-MetS, women have higher rates of depression, anxiety disorders, and pain comorbid with CVD and MetS. Thus, understanding the sex-dependent mechanisms that underlie these associations is important for the development of novel therapeutics to address the call for precision medicine.

Obesity (body mass index ≥30.0), when comorbid with MDD,15 is associated with greater severity16 and worse outcomes among those taking antidepressants17 and/or during weight loss treatment. The literature suggests that the comorbidity of MDD-obesity/MetS may be stronger among, and perhaps limited to, women.18 The rate of obesity is higher for women than men, and among women, those with MDD are more likely than nondepressed women to develop obesity.19 Given the public health crisis regarding obesity-related health conditions and expenditures, it is important to understand sex differences in pathways leading to obesity-related health diseases.

CVD (which is associated with obesity/MetS) is a major cause of mortality worldwide, with higher prevalence in men (40.5%) than women (35.5%),20 although CVD is the number one cause of death among women in the United States. Furthermore, as with MetS, women have an almost twofold higher prevalence than men of comorbid MDD-CVD, which is predicted to be the number one cause of disability worldwide by 2020.13,14 MDD also leads to a higher death rate among women with CVD.

MetS is a cluster of metabolic dysfunction comprising central obesity, dyslipidemia, impaired glucose metabolism, and hypertension.21 Approximately 30% of the US population exhibits MetS,22 which confers a twofold increased risk for CVD.20 Although the prevalence of MetS is similar (around 32%) among men and women (in contrast to CVD prevalence), its individual components vary by sex, with higher proportions of hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, low high-density lipid levels, and hyperglycemia in men and higher proportions of central adiposity in women.23 Thus, understanding the impact of sex on MetS may provide etiologic clues as to the nature of the comorbidity of MDD and CVD, and it may be one reason why there is a higher death rate from CVD among women, even though CVD prevalence is lower than in men.

Role of HPA and HPG steroid hormones

Dysregulation of HPA and HP-gonadal (HPG) axes has been independently implicated in the pathogenesis of both MDD and obesity/MetS. Cushing syndrome, characterized by excess cortisol (glucocorticoid; GC), has a higher prevalence among women and is associated with cardiometabolic complications, including obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, and hypertension.24 The HPA overactivity observed among obese compared with lean patients is associated with abdominal obesity, MetS, and high blood pressure.25 Obese women have higher corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)-stimulated cortisol levels than men,25 even though men have higher levels of basal cortisol than women.

Studies linking the association of stress and GC response with the development of obesity/MetS in humans are limited because of a lack of longitudinal data and difficulty in assessing subtle changes in local tissue via autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. GCs promote adipocyte differentiation and proliferation26 where visceral adipocytes have high GC receptor distribution. There are some genetic polymorphisms in glucocorticoid receptors associated with alterations in GCs, obesity,27 and comorbid obesity-MDD,28 although their roles are unclear. Proposed mechanisms linking HPA activity and obesity/MetS include alterations in GC metabolism in adipose tissue depots29 and interactions of cortisol with high-fat diet and key appetite-regulating hormones, such as leptin and ghrelin (see below).

In response to an energy deficit, cortisol rises and facilitates food intake and fat deposition.30 Among obese women, cortisol is decreased or similar to healthy-weight women, increased after food intake31 or in response to social stress,32 and decreased after weight loss. Mechanisms explaining these findings include direct central nervous system action in tissues with high GC receptor concentration,33 in regions that are sexually dimorphic and regulate mood. Therefore, we suggest that disruptions in the development of these regions will produce multiple systemic endocrine and metabolic effects.13-14

The PVN, the key relay station for HPA activity, develops differently in male and female brains,34 is the most highly vascularized central nervous system region,35 and is important for regulating homeostatic, neuroendocrine, and behavioral functions associated with MDD.36-38 Furthermore, the PVN is an essential component of brain circuitries important for feeding and energy balance and can regulate the ANS, which is critical for healthy cardiovascular responses. Thus, understanding the role of the PVN may be critical for understanding the impact of HPA activity on sex differences in the comorbidities among MDD, MetS, and CVD.14

Gonadal steroids are also associated with MetS and CVD. Abnormalities in estradiol levels among obese women compared with healthy-weight women may be decreased, elevated, or show no differences.39 Estrogens affect body weight and food intake, which vary with reproductive age. Premenopausal women demonstrated decreased food intake during the follicular phase, and during postmenopause, estrogen levels are reduced and circulate proportionally to body fat.40 Estrogen receptors are found in food reward regions41-44 and act to suppress appetite and increase energy expenditure. Hyperandrogenic conditions in women (hirsutism and polycystic ovary syndrome) are associated with CVD, insulin resistance, visceral fat accumulation, and MetS,45 but low circulating testosterone in men is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and MetS.46 Thus, dysregulation of gonadal steroid levels is associated with cardiometabolic phenotypes in women and men. The presence of comorbid MDD and insulin resistance was underscored by recent findings from a large population study (n=12 231) using the Northern Finland Birth Cohort from 1966, which demonstrated the emergence of comorbid MDD and insulin resistance in women only after menopause, but in men, onset occurred at an earlier age.47

There is a very long history of studies of HPA dysregulation associated with MDD, in particular, heightened cortisol levels, that may become blunted among those with long-term, recurrent MDD. However, these studies will not be reviewed here, given extensive reviews elsewhere.48-52 In brief, depressive symptoms can occur in the face of endogenously elevated cortisol (Cushing syndrome) or of exogenously administered corticosteroids.53 Patients treated with corticosteroids can develop MDD.54 Human studies demonstrate consistent HPA-axis dysregulation associated with MDD, including elevated plasma and cerebral spinal fluid cortisol levels and 24-hour urinary cortisol levels, high cerebral spinal fluid CRH levels, blunted responses to CRH administration, and lack of negative feedback suppression by dexamethasone.

HPG deficits in MDD52 include lower estradiol levels,38-55 and adjunctive estradiol has been found effective in treating MDD among women.56 This observation has been reviewed elsewhere so will not be reviewed here. In brief, women's reproductive variability and aging are related to mood fluctuations and MDD.57-60 In women, MDD incidence increases with puberty,61 late luteal phase,62 and long-term use of oral contraceptives,63 after childbirth64 and after menopause.65 Population studies demonstrated that ovarian dysfunction precedes MDD onset.58 Aside from estradiol abnormalities, deficits have been found in luteinizing hormone and pituitary function.55,58,66

The comorbidity between MDD, HPA-HPG-axis dysregulation, and MetS risk is not surprising from the perspective of the brain circuitry involved. MDD involves hypothalamic nuclei central/medial amygdala, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex, and medial and orbitofrontal cortices67-70—regions that are dense in glucocorticoid and sex steroid hormone receptors71-73 and that can relay information that regulates metabolic and cardiac function through the ANS. Reduced gray-matter volume has been noted within several of these regions in MDD patients, including the anterior cingulate,74,75 orbitofrontal cortex,74,75 prefrontal cotex,74,76 insula,75 putamen,74 caudate nucleus,74 and hippocampus74,76,77 and adjacent temporal lobes,75,76 as demonstrated in recent large meta-analyses focused on volumetric74 and cortical thickness75,76 indices. More nuanced analyses have revealed effects of medication on the amygdala, in which decreases in amygdala volume are associated with some specificity to nonmedicated status.78 In the hippocampus, volumetric variation has been associated with clinical state, with reduced hippocampal volume evident in first-episode depression,79 currently depressed but not remitted patients,80 recurrent MDD, or prolonged (> 1 year) illness duration.81,82 These findings suggest a critical link between lowered mood state and hippocampal structural integrity that is potentially related to abnormal HPA-axis feedback on glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus. Differences in results from studies identifying brain abnormalities in MDD are, in part, a function of methodological variability across studies, such as MDD chronicity (eg, acute versus chronic disability), sex and age of subjects, sample sizes, and/or measurement of brain regions. However, there is consistent evidence that deficits in these brain regions originating during fetal development have had lifelong consequences for sex differences in the risk for MDD-MetS comorbidity, dependent on brain region and age of assessments.

Appetite-regulating hormones

One pathway through which mood and metabolic function co-occur may be related to the overlap of brain regions that regulate mood, HPA, HPG, and ANS. These areas are dense with receptors for ghrelin and leptin, two peptides that are involved in hunger and satiety.83 Ghrelin is a potent orexigenic peptide, with levels rising sharply before meals and falling to nadir within an hour after eating.84 Ghrelin receptors are located in the substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, raphe nuclei, hypothalamic nuclei (PVN, arcuate, and ventromedial), and hippocampus85; direct ghrelinergic projections connect the PVN to amygdala.85 Intravenous ghrelin administration heightens neural activation in these brain regions in response to food images.86 Ghrelin levels are decreased in obesity, and plasma ghrelin levels negatively correlate with percent body fat during fasting, whereas increases in ghrelin occur after weight loss. Circulating ghrelin levels are higher among women than men,87 and in postmenopausal obese women, they are inversely related to estradiol.88 Reported ghrelin levels among healthy-weight persons and MDD status are inconsistent across studies. Among healthy-weight individuals with MDD, ghrelin has been reported as elevated, decreased,89 or similar90 to that in individuals without MDD. Inconsistencies in MDD studies may be due to the lack of control for sex, given that women have higher levels of circulating ghrelin than men.

In contrast, leptin suppresses appetite by effects at similar hypothalamic sites, and it stimulates energy expenditure. Leptin circulates in proportion to fat mass, signaling energy availability and satiety, and is generally higher among women than men, beginning in puberty,91 even after accounting for differences in body fat distribution and menopause.92 Leptin receptors are located within many brain regions,93 some of which are sexually dimorphic and overlap areas involved in mood and stress regulation. Though circulating leptin follows a pulsatile release pattern, decreases in leptin occur with fasting,94 and basal plasma leptin levels are elevated in obesity.94

Recent evidence links inflammatory adipokines and ghrelin-growth hormone (GH) axis with obesity and MDD.95 Adiponectin is an anti-inflammatory peptide secreted by adipocytes and plays a role in fetal growth96 and endothelial function.97 Women exhibit higher adiponectin levels than men,98 and reports suggest a sex-dependent role of adiponectin as a biomarker for CVD and diabetes risk.99 Low adiponectin levels are associated with depressive-like behaviors, and genetic haploin-sufficiency of adiponectin (Adipo+/-) causes depression-like behavior and impaired HPA-axis feedback, which are reversed by intracerebroventricular adiponectin administration.100

Collectively, although disruption of peptides involved in appetite regulation is well documented in obesity, mixed findings in MDD suggest attention to sex and variability in weight may explain inconsistencies across studies. Given the overlap of a number of regulatory peptides in key brain regions (eg, hypothalamus, mesolimbic circuitry) and their roles in the pathophysiology of sex differences in MDD-obesity/MetS, systematic designs stratifying subject groups by MDD and obesity status by sex would allow for delineation of shared and unshared pathways contributing to understanding brain abnormalities associated with metabolic and mood dysregulation and sex differences therein.

Fetal origins: mapping developmental pathways to comorbidity

There is emerging evidence that alterations in HPA axis and stress adaptation in response to suboptimal conditions in utero produce disturbances in fetal metabolism and development of obesity and MDD in adulthood. Sex differences in MDD alone and in comorbid MDD-CVD have been reviewed elsewhere.13,14,52 Epidemiological evidence shows increased incidence of obesity and diabetes as a result of severe maternal malnutrition,101 possibly secondary to effects on early fetal programming of the HPA axis. Obstetric complications, such as preeclampsia and low birth weight, have been found to be significant risk factors for MDD and cardiometabolic outcomes.2,5,6 Nonetheless, beyond few population-level investigations, sex differences in fetal programming of comorbid MDD-MetS has not been well examined, owing largely to a paucity of longitudinal datasets that are able to address these critical fetal developmental models that have already been established for animals.

Excessive maternal glucocorticoid responses to stress are also associated with maternal inflammatory responses. Altered levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, and IL-10 in maternal sera during gestation5,7,102,103 are associated with preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction and adult risk for CVD and MDD. These cytokines are also associated with maternal HPA dysregulation. TNF-α, IL-lβ, and IL-6 are the primary coactivators of HPA response, and their receptors are located in PVN, hippocampus, and pituitary. We recently reported that maternal prenatal immune dysregulation has an impact on sex differences in the adult offspring MDD risk.4 In fact, elevated IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α have been associated with CVD risk104,105 and MetS.106

Few human studies have directly linked maternal markers of immune function during gestation with MetS risk among adult offspring by sex. However, preclinical studies are leading the way in mapping out pathways implicated in the fetal stress-immune programming of sex differences in the comorbidity of mood and anxiety-related behaviors and cardiometabolic dysfunction (Figure 1).

Preclinical evidence

In rodents, prenatal synthetic glucocorticoid (sGC) exposure or inhibition of 11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD; a placental enzyme that metabolizes GCs and acts as barrier to maternal GCs.107) can cause long-term adult changes in cardiometabolic function and neuroendocrine responses to stress and anxiety-and depressive-like behaviors.108 As in humans, the neuropeptide neurons in the PVN are key in regulating the HPA axis. Similarly, the ANS is controlled in part by preautonomic neurons located within the rat PVN that project to preganglionic autonomic neurons located in the brainstem and spinal column.109

The timing of prenatal stressors will have very different effects on physiological systems because various tissues and brain regions develop and mature at different times of gestation. Moreover, the ability to extrapolate the effects of environmental perturbations in experimental animals to humans is complicated by differences in gestation length and maturation rate.110,111

Cardiovascular system and metabolism

Exposure to prenatal stressors, including sGC administration, dietary restriction, and inflammation, can program changes in cardiovascular function in male and female rodent offspring, with increased vascular sensitivity to norepinephrine,112,113 neuropeptide Y,114 and electrical field stimulation114; increased peripheral resistance and reduced cardiac output115; and hypertension116,117 or hypotension altering stress responses.112,118 In females alone, prenatal stressors resulted in enhanced endothelin responsiveness119 and impaired parasympathetic function (although males were not tested in the latter).120 Adult offspring of prenatally stressed dams were more susceptible to elevations in blood pressure in response to high salt diet,121 angiotensin II,113 and restraint.112,114,122 As in humans, prenatal GC exposures in rodents are coupled with inflammatory responses, known to be associated with hypertension and heart disease. Prenatal exposure to IL-6 causes hypertension and enhanced cardiovascular responses to stress, with a greater effect in females.123

Epigenetic changes are associated with cardiovascular programming from prenatal stress. Prenatal GCs reduced global DNA methylation in the kidney, adrenal glands, and cerebellum in adult offspring.124 There is some evidence for increased methylation related to an altered renin-angiotensin system (RAS; a major regulator of long-term control of blood pressure), where prenatal sGC altered the expression of angiotensin receptors,117,118,125 renal angiotensin II production,126 and plasma renin activity.127 However, the direction of the RAS activity in male versus female offspring varied with the nature or timing of prenatal stress. Enhanced RAS activity was observed after prenatal exposure to sGCs, demonstrating that acute angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor blockade lowered blood pressure—partially normalizing parasympathetic dysfunction—and fully normalized blood pressure variability in adult male sheep (females not tested).120 A maternal low-protein diet caused corticosterone-dependent increases in angiotensin 1b receptor gene (AT1b) expression coupled with reduced methylation of the AT1b promoter.128 Importantly, in addition to changes in angiotensin receptor expression, inhibition of corticosterone production in utero prevented hypertension in these offspring.128 Prenatal stress also altered central RAS activity. Central infusion of the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan reduced blood pressure and heart rate in sGC-treated versus control male sheep (females not tested).129 Prenatal sGC exposure also increased AT1 expression in brainstem of adult offspring129 and increased angiotensin II levels relative to the protective Ang(1-7) peptide levels in the dorsal medulla.130 Together, these studies suggest that prenatal stress alters the RAS by programming the expression of angiotensin receptors during gestation.

Animal studies also demonstrated that late-gestation stressors predisposed offspring to MetS in adulthood.131,132 Moreover, late-gestation exposure to sGC increased liver enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis in adult male, but not female, offspring127,133 and altered production of insulin by reducing pancreatic β-cells and their capacity to secrete insulin.134 Prenatal GCs also increased circulating triglycerides and storage of fat in the liver135 and decreased fatty acid uptake in visceral adipose tissue.136 Most of these studies were restricted to adult male offspring; however, we previously demonstrated that high-fat-diet-induced hepatosteatosis was more profound in female offspring of dexamethasone-treated dams, and this was coupled with sex-specific changes in circulating insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGFl).137 Taken together, these studies highlight the role of prenatal GC exposure, whether from prenatal stress or treatment with sGC, on the impact of glucose homeostasis programming and risk for adult MetS.

In fact, prenatal stress programming of MetS may be initiated very early in gestation and have sex-selective effects expressed as different metabolic phenotypes in males and females. An example of this was found in studies of O-linked βN-acetyl glucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase (OGT). This enzyme, expressed by the placenta, senses changes in maternal energy homeostasis and regulates epigenetic marks on chromatin.138 Early gestational stress reduces placental OGT, giving rise to changes in offspring endocrine and hypothalamic mitochondrial function and body weight.139,140 Reductions in placental OGT were only found in male placentas, suggesting a pathway whereby early changes in placental OGT regulated sex-selective epigenetic modification of genes important for adult metabolism.

Gestational stress can also foster MetS by organizing hypothalamic nuclei that control energy homeostasis.141 Leptin is important for the development of both orexigenic and anorexigenic projections from the arcuate nucleus142 and acts during development to regulate autonomic centers controlling peripheral tissues in adulthood.143 A surge of circulating leptin occurs in development and peaks about postnatal day (PD) 9 to 12 in male and female rats.144 Gestational malnutrition advanced the leptin surge, leading to hypothalamic leptin insensitivity in adult male offspring (females not tested),145 and delaying the postnatal leptin surge led to diet-induced obesity in female rats (males not tested).146 Similarly, intrauterine growth restriction caused hyperleptinemia followed by leptin resistance by PD21 in female, but not male, rats,147 whereas a leptin antagonist increased food intake in adult male, but not female, offspring.148 Together, these studies suggest sex-dependent roles for the postnatal surge of leptin in the development of hypothalamic regulation of energy balance in adulthood.

Adult behavior and neuroendocrine function

Prenatal stressors in rodents also program the HPA axis, causing increased stress responsiveness,149-151 and this is mimicked by prenatal exposure to glucocorticoids.152 The impact of late-gestation prenatal stress on adult stress responsivity is more profound in adult female offspring,153-155 where prenatal stressors increase basal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and corticosterone levels and the peak and duration of responses to adult stressors,152,153 indicative of reductions in GC negative feedback. Supporting this, Tobe and colleagues detected increased apoptosis in the fetal female, but not male, PVN after long-term maternal stress,156 and this correlated with changes in neuroendocrine function and anxiolytic behaviors.153 Moreover, late-gestation sGCs resulted in increased anxiety and depressive-like behaviors in adult female, but not male, offspring,157 suggesting potential sex-dependent pathways to sex differences in mood and anxiety disorders.

A recent study provided evidence of potential sex-dependent targets for the long-term effects of prenatal stress and GCs.158 In females, upregulation of 5α-reductase and 3β-HSD in adults that were prenatally stressed was effective in reversing programming effects on the HPA-axis response to IL-1β administration. Thus, timing of environmental perturbations is critical for the sex-dependent alterations in the development of HPA-axis responses in adulthood, suggesting the potential for sex-specific critical periods for the actions of perinatal GCs. Nonetheless, the system appears to retain sufficient plasticity to allow deficits to be overcome by later manipulations. Given that sex-dependent changes can occur after prenatal perturbations, future studies need to determine the importance of central versus peripheral changes in the RAS, HPA axis, and metabolic markers involved and how they impact sex-dependent long-term changes in cardiovascular, metabolic, and behavioral-associated diseases.

Conclusion

In summary, clinical and preclinical studies demonstrate the impact of prenatal stress-immune programming of sex differences in adult risk for mood and anxiety and ANS, metabolic, and cardiac dysfunctions. The sex-dependent impact is timing specific during gestation and brain-region specific, resulting in multiple systemic sex-dependent effects on HPA-HPG axes and on metabolic and cardiac functions, leading to sex differences in the comorbidity of MDD-obesity/MetS. Translational studies are critical to map out the specificity of these developmental pathways among men and women. The developmental nature and preclinical evidence for some reversibility of effects suggests optimism for early intervention with sex-dependent novel therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The work for this article was supported by a program project grant from the State of Arizona Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (ABRC) ADHS14-00003606 (Handa, overall PI; Goldstein, PI, human studies). We would like to thank Stuart Tobet, PhD for previous work with us on the topic of comorbidity of depression and CVD that forms the basis of some of the scientific framework in this review. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Selected abbreviations and acronyms

- ANS

autonomic nervous system

- AT1

angiotensin II type 1

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- GC

glucocorticoid

- HPA

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- HPG

hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal

- IL

interleukin

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- MetS

metabolic syndrome

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- RAS

renin-angiotensin system

Contributor Information

Jill M. Goldstein, Connors Center for Women's Health and Gender Biology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Laura Holsen, Connors Center for Women's Health and Gender Biology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Grace Huang, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Bradley D. Hammond, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix, Phoenix, Arizona, USA; Department of Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Tamarra James-Todd, Connors Center for Women's Health and Gender Biology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Sara Cherkerzian, Connors Center for Women's Health and Gender Biology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Taben M. Hale, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix, Phoenix, Arizona, USA.

Robert J. Handa, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix, Phoenix, Arizona, USA; Department of Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Global health estimates 2014 summary tables: YLD by cause, age, and sex, 2000-2012. Available at: http://www. who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index2.html. Published June 2014. Accessed October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts RE., Deleger S., Strawbridge WJ., Kaplan GA. Prospective association between obesity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(4):514–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang L., Colditz GA. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 2007-2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1412–1413. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilman SE., Cherkerzian S., Buka SL., Hahn J., Hornig M., Goldstein JM. Prenatal immune programming of sex-dependent risk for major depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(5):e822. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein JM., Cherkerzian S., Buka SL., et al Sex-specific impact of maternal-fetal risk factors on depression and cardiovascular risk 40 years later. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2011;6(2):353–364. doi: 10.1017/S2040174411000651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van OS J., Jones P., Lewis G., Wadsworth M., Murray R. Developmental precursors of affective illness in a general population birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(7):625–631. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190049005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salam RA., Das JK., Bhutta ZA. Impact of intrauterine growth restriction on long-term health. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17(3):249–254. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McEwen BS. Gonadal steroid influences on brain development and sexual differentiation. In: Creep R, ed. Reproductive Physiology IV: International Review of Physiology. Vol 27. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press. 1983:99–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobet S., Knoll JG., Hartshorn C., et al Brain sex differences and hormone influences: a moving experience? J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21(4):387–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giedd JN., Vaituzis AC., Hamburger SD., et al Quantitative MRI of the temporal lobe, amygdala, and hippocampus in normal human development: ages 4-18 years. J Comp Neurol. 1996;366(2):223–230. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960304)366:2<223::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein JM., Seidman LJ., Horton NJ., et al Normal sexual dimorphism of the adult human brain assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11(6):490–497. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makris N., Swaab DF., van der Kouwe A., et al Volumetric parellation methodology of the human hypothalamus in neuroimaging: normative data and sex differences. Neuroimage. 2013;69:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein JM., Handa RJ., Tobet SA. Disruption of fetal hormonal programming (prenatal stress) implicates shared risk for sex differences in depression and cardiovascular disease. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35(1):140–158. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobet S., Handa R., Goldstein JM. Sex-dependent pathophysiology as predictors of comorbidity of major depressive disorder and cardiovascular disease. Pflugers Arch. 2013;465(5):585–594. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1248-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Needham BL., Epel ES., Adler NE., Kiefe C. Trajectories of change in obesity and symptoms of depression the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1040–1046. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy JM., Horton NJ., Burke JD Jr., et al Obesity and weight gain in relation to depression: findings from the Stirling County Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(3):335–341. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kloiber S., Ising M., Reppermund S., et al Overweight and obesity affect treatment response in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(4):321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heo M., Pietrobelli A., Fontaine KR., Sirey JA., Faith MS. Depressive mood and obesity in US adults: comparison and moderation by sex, age, and race. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006;30(3):513–519. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasler G., Pine DS., Kleinbaum DG., et al Depressive symptoms during childhood and adult obesity: the Zurich Cohort Study. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(9):842–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mozaffarian D., Benjamin EJ., Go AS., et al Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeFronzo RA., Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 1991;14(3):173–194. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James-Todd TM., Huang T., Seely EW., Saxena AR. The association between phthalates and metabolic syndrome: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2010. Environ Health. 2016;15:52. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beltran-Sanchez H., Harhay MO., Harhay MM., McElligott S. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult U.S. population, 1999-2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(8):697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bose M., Olivan B., Laferrere B. Stress and obesity: the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in metabolic disease. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009;16(5):340–346. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32832fa137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vicennati V., Ceroni L., Genghini S., Patton L., Pagotto U., Pasquali R. Sex difference in the relationship between the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sex hormones in obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(2):235–243. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bujalska IJ., Kumar S., Hewison M., Stewart PM. Differentiation of adipose stromal cells: the roles of glucocorticoids and 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Endocrinology. 1999;140(7):3188–3196. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.7.6868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelernter-Yaniv L., Feng N., Sebring NG., Hochberg Z., Yanovski JA. Associations between a polymorphism in the 11 beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type I gene and body composition. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(8):983–986. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivera M., Cohen-Woods S., Kapur K., et al Depressive disorder moderates the effect of the FTO gene on body mass index. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(6):604–611. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rask E., Olsson T., Soderberg S., et al Tissue-specific dysregulation of cortisol metabolism in human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(3):1418–1421. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mystkowski P., Schwartz MW. Gonadal steroids and energy homeostasis in the leptin era. Nutrition. 2000;16(10):937–946. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vicennati V., Ceroni L., Gagliardi L., Gambineri A., Pasquali R. Comment: response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis to high-protein/fat and high-carbohydrate meals in women with different obesity phenotypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(8):3984–3988. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benson S., Arck PC., Tan S., et al Effects of obesity on neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and immune cell responses to acute psychosocial stress in premenopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(2):181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McEwen BS., De Kloet ER., Rostene W. Adrenal steroid receptors and actions in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 1986;66(4):1121–1188. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1986.66.4.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClellan KM., Stratton MS., Tobet SA. Roles for gamma-aminobutyric acid in the development of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(14):2710–2728. doi: 10.1002/cne.22360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frahm KA., Schow MJ., Tobet SA. The vasculature within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in mice varies as a function of development, subnuclear location, and GABA signaling. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44(8):619–624. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1304624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao AM., Hestiantoro A., Van Someren EJ., Swaab DF., Zhou JN. Colocalization of corticotropin-releasing hormone and oestrogen receptor-α in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in mood disorders. Brain. 2005;128(pt 6):1301–1313. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein JM., Jerram M., Abbs B., Whitfield-Gabrieli S., Makris N. Sex differences in stress response circuitry activation dependent on female hormonal cycle. J Neurosci. 2010;30(2):431–438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3021-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobs EG., Holsen LM., Lancaster K., et al 17 -Estradiol differentially regulates stress circuitry activity in healthy and depressed women. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(3):566–576. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Pergola G., Maldera S., Tartagni M., Pannacciulli N., Loverro G., Giorgino R. Inhibitory effect of obesity on gonadotropin, estradiol, and inhibin B levels infertile women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(11):1954–1960. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Real JM., Sanchis D., Ricart W., et al Plasma oestrone-fatty acid ester levels are correlated with body fat mass in humans. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;50(2):253–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruijver FP., Balesar R., Espila AM., Unmehopa UA., Swaab DF. Estrogen receptor-α distribution in the human hypothalamus in relation to sex and endocrine status. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454(2):115–139. doi: 10.1002/cne.10416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kruijver FP., Balesar R., Espila AM., Unmehopa UA., Swaab DF. Estrogen-receptor-α distribution in the human hypothalamus: similarities and differences with ERα distribution. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466(2):251–277. doi: 10.1002/cne.10899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Österlund MK., Gustafsson JA., Keller E., Hurd YL. Estrogen receptor β (ERβ) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression within the human forebrain: distinct distribution pattern to ER mRNA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(10):3840–3846. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osterlund MK., Keller E., Hurd YL. The human forebrain has discrete estrogen receptor α messenger RNA expression: high levels in the amygdaloid complex. Neuroscience. 2000;95(2):333–342. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janssen I., Powell LH., Kazlauskaite R., Dugan SA. Testosterone and visceral fat in midlife women: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) fat patterning study. Obesity. 2010;18(3):604–610. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derby CA., Zilber S., Brambilla D., Morales KH., McKinlay JB. Body mass index, waist circumference and waist to hip ratio and change in sex steroid hormones: the Massachusetts Male Ageing Study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;65(1):125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eskola PJ., Jokelainen J., Jarvelin MR., et al Depression and insulin resistance: additional support for the novel heuristic model in perimenopausal depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):796–797. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holsboer F., Gerken A., Stalla GK., Muller OA. Blunted aldosterone and ACTH release after human CRH administration in depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(2):229–231. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nemeroff CB., Widerlov E., Bissette G., et al Elevated concentrations of CSF corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in depressed patients. Science. 1984;226(4680):1342–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.6334362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plotsky PM., Owens MJ., Nemeroff CB. Psychoneuroendocrinology of depression. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21(2):293–307. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raison CL., Miller AH. When not enough is too much: the role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(9):1554–1565. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldstein JM., Holsen L., Handa R., Tobet S. Fetal hormonal programming of sex differences in depression: linking women's mental health with sex differences in the brain across the lifespan. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:247. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelly WF., Checkley SA., Bender DA. Cushing's syndrome, tryptophan and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:125–132. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ling MH., Perry PJ., Tsuang MT. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. Psychiatric aspects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):471–477. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290105011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young EA., Midgley AR., Carlson NE., Brown MB. Alteration in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis in depressed women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(12):1157–1162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Epperson CN., Wisner KL., Yamamoto B. Gonadal steroids in the treatment of mood disorders. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(5):676–697. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199909000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Payne JL., Palmer JT., Joffe H. A reproductive subtype of depression: conceptualizing models and moving toward etiology. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17(2):72–86. doi: 10.1080/10673220902899706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harlow BL., Wise LA., Otto MW., Scares CN., Cohen LS. Depression and its influence on reproductive endocrine and menstrual cycle markers associated with perimenopause: the Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubinow DR., Schmidt PJ. Androgens, brain, and behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(8):974–984. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roca CA., Schmidt PJ., Altemus M., et al Differential menstrual cycle regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in women with premenstrual syndrome and controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(7):3057–3063. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Angold A., Costello EJ. Puberty and depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(4):919–937, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steiner M. Female-specific mood disorders. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1992;35(3):599–611. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199209000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young EA., Kornstein SG., Harvey AT., et al Influences of hormone-based contraception on depressive symptoms in premenopausal women with major depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(7):843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brummelte S., Galea LA. Depression during pregnancy and postpartum: contribution of stress and ovarian hormones. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(5):766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Graziottin A., Serafini A. Depression and the menopause: why antidepressants are not enough? Menopause Int. 2009;15(2):76–81. doi: 10.1258/mi.2009.009021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daly RC., Danaceau MA., Rubinow DR., Schmidt PJ. Concordant restoration of ovarian function and mood in perimenopausal depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1842–1846. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dougherty D., Rauch SL. Neuroimaging and neurobiological models of depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;5(3):138–159. doi: 10.3109/10673229709000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drevets WC., Price JL., Bardgett ME., Reich T., Todd RD., Raichle ME. Glucose metabolism in the amygdala in depression: relationship to diagnostic subtype and plasma Cortisol levels. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71(3):431–447. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00687-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mayberg HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9(3):471–481. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sheline YI., Mittler BL., Mintun MA. The hippocampus and depression. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17((suppl 3)):300–305. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00655-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Handa RJ., Burgess LH., Kerr JE., O'Keefe JA. Gonadal steroid hormone receptors and sex differences in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Horm Behav. 1994;28(4):464–476. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kawata M. Roles of steroid hormones and their receptors in structural organization in the nervous system. Neurosci Res. 1995;24(1):1–46. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(96)81278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ostlund H., Keller E., Hurd YL. Estrogen receptor gene expression in relation to neuropsychiatric disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1007:54–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koolschijn PC., van Haren NE., Lensvelt-Mulders GJ., Hulshoff Pol HE., Kahn RS. Brain volume abnormalities in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(11):3719–3735. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmaal L., Hibar DP., Samann PG., et al Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry. 2016 May 3. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1038/ mp. 2016.60. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arnone D., Job D., Selvaraj S., et al Computational meta-analysis of statistical parametric maps in major depression. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(4):1393–1404. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Campbell S., Marriott M., Nahmias C., MacQueen GM. Lower hippocampal volume in patients suffering from depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):598–607. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamilton JP., Siemer M., Gotlib IH. Amygdala volume in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(11):993–1000. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cole J., Costafreda SG., McGuffin P., Fu CH. Hippocampal atrophy in first episode depression: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):483–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kempton MJ., Salvador Z., Munafo MR., et al Structural neuroimaging studies in major depressive disorder. Meta-analysis and comparison with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):675–690. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McKinnon MC., Yucel K., Nazarov A., MacQueen GM. A meta-analysis examining clinical predictors of hippocampal volume in patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34(1):41–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Videbech P., Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1957–1966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saper CB., Chou TC., Elmquist JK. The need to feed: homeostatic and hedonic control of eating. Neuron. 2002;36(2):199–211. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cummings DE., Purnell JQ., Frayo RS., Schmidova K., Wisse BE., Weigle DS. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1714–1719. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nakazato M., Murakami N., Date Y., et al A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409(6817):194–198. doi: 10.1038/35051587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Malik S., McGlone F., Bedrossian D., Dagher A. Ghrelin modulates brain activity in areas that control appetitive behavior. Cell Metab. 2008;7(5):400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Soriano-Guillén L., Ortega L., Navarro P., Riestra P., Gavela-Pérez T., Garcés C. Sex-related differences in the association of ghrelin levels with obesity in adolescents. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54(8):1371–1376. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Karim R., Stanczyk FZ., Brinton RD., Rettberg J., Hodis HN., Mack WJ. Association of endogenous sex hormones with adipokines and ghrelin in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;100(2):508–515. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barim AO., Aydin S., Colak R., Dag E., Deniz O., Sahin I. Ghrelin, paraoxonase and arylesterase levels in depressive patients before and after citalopram treatment. Clin Biochem. 2009;42(10-11):1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kluge M., Schussler P., Schmid D., et al Ghrelin plasma levels are not altered in major depression. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;59(4):199–204. doi: 10.1159/000223731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ahmed ML., Ong KK., Morrell DJ., et al Longitudinal study of leptin concentrations during puberty: sex differences and relationship to changes in body composition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(3):899–905. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.3.5559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Saad MF., Damani S., Gingerich RL., et al Sexual dimorphism in plasma leptin concentration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(2):579–584. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garza JC., Guo M., Zhang W., Lu XY. Leptin increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):18238–18247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800053200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Korbonits M., Trainer PJ., Little JA., et al Leptin levels do not change acutely with food administration in normal or obese subjects, but are negatively correlated with pituitary-adrenal activity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997;46(6):751–757. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.1820979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hryhorczuk C., Sharma S., Fulton SE. Metabolic disturbances connecting obesity and depression. Front Neurosci. 2013;14(1):83–144. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Briana DD., Malamitsi-Puchner A. The role of adipocytokines in fetal growth. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1205:82–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu W., Cheng KK., Vanhoutte PM., Lam KS., Xu A. Vascular effects of adiponectin: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic intervention. Clin Sci (Lond). 2008;114(5):361–374. doi: 10.1042/CS20070347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Boyne MS., Bennett NR., Cooper RS., et al Sex-differences in adiponectin levels and body fat distribution: longitudinal observations in Afro-Jamaicans. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90(2):e33–e36. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Donahue RP., Rejman K., Rafalson LB., Dmochowski J., Stranges S., Trevisan M. Sex differences in endothelial function markers before conversion to pre-diabetes: does the clock start ticking earlier among women? The Western New York Study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):354–359. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu J., Guo M., Zhang D., et al Adiponectin is critical in determining susceptibility to depressive behaviors and has antidepressant-like activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(30):12248–12253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202835109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ravelli AC., van der Meulen JH., Michels RP., et al Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. Lancet. 1998;351(9097):173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Haggerty CL., Ferrell RE., Hubel CA., Markovic N., Harger G., Ness RB. Association between allelic variants in cytokine genes and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sanchez SE., Zhang C., Williams MA., et al Tumor necrosis factor-α soluble receptor p55 (sSex Difp55) and risk of preeclampsia in Peruvian women. J Reprod Immunol. 2000;47(1):49–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(99)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Naghavi M., Wyde P., Litovsky S., et al Influenza infection exerts prominent inflammatory and thrombotic effects on the atherosclerotic plaques of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2003;107(5):762–768. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048190.68071.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Libby P., Ridker PM., Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105(9):1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mirhafez SR., Pasdar A., Avan A., et al Cytokine and growth factor profiling in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(12):1911–1919. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cottrell EC., Seckl JR., Holmes MC., Wyrwoll CS. Foetal and placental 11β-HSD2: a hub for developmental programming. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2014;210(2):288–295. doi: 10.1111/apha.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Holmes MC., Wyrwoll C., Seckl J. Fetal programming of adult behaviour by stress and glucocorticoids. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;61:9. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Handa RJ., Weiser MJ. Gonadal steroid hormones and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35(2):197–220. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Workman AD., Charvet CJ., Clancy B., Darlington RB., Finlay BL. Modeling transformations of neurodevelopmental sequences across mammalian species. J Neurosci. 2013;33(17):7368–7383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5746-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bayer SA., Altman J., Russo RJ., Zhang X. Timetables of neurogenesis in the human brain based on experimentally determined patterns in the rat. Neurotoxicology. 1993;14(1):83–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.O'Regan D., Kenyon CJ., Seckl JR., Holmes MC. Prenatal dexamethasone 'programmes' hypotension, but stress-induced hypertension in adult offspring. J Endocrinol. 2008;196(2):343–352. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hadoke PW., Lindsay RS., Seckl JR., Walker BR., Kenyon CJ. Altered vascular contractility in adult female rats with hypertension programmed by prenatal glucocorticoid exposure. J Endocrinol. 2006;188(3):435–442. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lgosheva N., Taylor PD., Poston L., Glover V. Prenatal stress in the rat results in increased blood pressure responsiveness to stress and enhanced arterial reactivity to neuropeptide Y in adulthood. J Physiol. 2007;582(pt 2):665–674. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.130252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Moritz KM., Dodic M., Jefferies AJ., et al Haemodynamic characteristics of hypertension induced by prenatal Cortisol exposure in sheep. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009;36(10):981–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rogers JM., Ellis-Hutchings RG., Grey BE., et al Elevated blood pressure in offspring of rats exposed to diverse chemicals during pregnancy. Toxicol Sci. 2014;137(2):436–446. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gwathmey TM., Shaltout HA., Rose JC., Diz Dl., Chappell MC. Glucocorticoid-induced fetal programming alters the functional complement of angiotensin receptor subtypes within the kidney. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):620–626. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.164970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.O'Sullivan L., Cuffe JS., Koning A., Singh RR., Paravicini TM., Moritz KM. Excess prenatal corticosterone exposure results in albuminuria, sex-specific hypotension, and altered heart rate responses to restraint stress in aged adult mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;308(10):F1065–F1073. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00676.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee JH., Zhang J., Flores L., Rose JC., Massmann GA., Figueroa JP. Antenatal betamethasone has a sex-dependent effect on the in vivo response to endothelin in adult sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304(8):R581–R587. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00579.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shaltout HA., Rose JC., Chappell MC., Diz Dl. Angiotensin-(1-7) deficiency and baroreflex impairment precede the antenatal betamethasone exposure-induced elevation in blood pressure. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):453–458. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.185876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tang JI., Kenyon CJ., Seckl JR., Nyirenda MJ. Prenatal overexposure to glucocorticoids programs renal 11-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 expression and salt-sensitive hypertension in the rat. J Hypertens. 2011;29(2):282–289. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328340aa18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Igosheva N., Klimova O., Anishchenko T., Glover V. Prenatal stress alters cardiovascular responses in adult rats. J Physiol. 2004;557(pt 1):273–285. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.056911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Samuelsson AM., Ohrn I., Dahlgren J., et al Prenatal exposure to interleukin-6 results in hypertension and increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in adult rats. Endocrinology. 2004;145(11):4897–4911. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Crudo A., Petropoulos S., Moisiadis VG., et al Prenatal synthetic glucocorticoid treatment changes DNA methylation states in male organ systems: multigenerational effects. Endocrinology. 2012;153(7):3269–3283. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cuffe JS., Burgess DJ., O'Sullivan L., Singh RR., Moritz KM. Maternal corticosterone exposure in the mouse programs sex-specific renal adaptations in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in 6-month offspring. Physiol Rep. 2016;4(8. doi:10.14814/phy2.12754) doi: 10.14814/phy2.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dagan A., Gattineni J., Habib S., Baum M. Effect of prenatal dexamethasoneon postnatal serum and urinary angiotensin II levels. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(4):420–424. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.O'Regan D., Kenyon CJ., Seckl JR., Holmes MC. Glucocorticoid exposure in late gestation in the rat permanently programs gender-specific differences in adult cardiovascular and metabolic physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287(5):E863–E870. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00137.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bogdarina I., Haase A., Langley-Evans S., Clark AJ. Glucocorticoid effects on the programming of AT1b angiotensin receptor gene methylation and expression in the rat. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dodic M., McAlinden AT., Jefferies AJ., et al Differential effects of prenatal exposure to dexamethasone or Cortisol on circulatory control mechanisms mediated by angiotensin II in the central nervous system of adult sheep. J Physiol. 2006;571(pt 3):651–660. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Marshall AC., Shaltout HA., Nautiyal M., Rose JC., Chappell MC., Diz Dl. Fetal betamethasone exposure attenuates angiotensin-(1-7)-Mas receptor expression in the dorsal medulla of adult sheep. Peptides. 2013;44:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cottrell EC., Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of adult disease. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:19. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.019.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Harris A., Seckl J. Glucocorticoids, prenatal stress and the programming of disease. Horm Behav. 2011;59(3):279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nyirenda MJ., Lindsay RS., Kenyon CJ., Burchell A., Seckl JR. Glucocorticoid exposure in late gestation permanently programs rat hepatic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucocorticoid receptor expression and causes glucose intolerance in adult offspring. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(10):2174–2181. doi: 10.1172/JCI1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Dumortier O., Theys N., Ahn MT., Remade C., Reusens B. Impairment of rat fetal beta-cell development by maternal exposure to dexamethasone during different time-windows. PLoS One. 2011;6(10: e25576. doi:101371/journal.pone.0025576.) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Drake AJ., Raubenheimer PJ., Kerrigan D., Mclnnes KJ., Seckl JR., Walker BR. Prenatal dexamethasone programs expression of genes in liver and adipose tissue and increased hepatic lipid accumulation but not obesity on a high-fat diet. Endocrinology. 2010;151(4):1581–1587. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Cleasby ME., Kelly PA., Walker BR., Seckl JR. Programming of rat muscle and fat metabolism by in utero overexposure to glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 2003;144(3):999–1007. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Carbone DL., Zuloaga DG., Hiroi R., Foradori CD., Legare ME., Handa RJ. Prenatal dexamethasone exposure potentiates diet-induced hepatosteatosis and decreases plasma IGF-I in a sex-specific fashion. Endocrinology. 2012;153:295–306. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Nugent BM., Bale TL. The omniscient placenta: metabolic and epigenetic regulation of fetal programming. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2015;39:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Howerton CL., Bale TL. Targeted placental deletion of OGT recapitulates the prenatal stress phenotype including hypothalamic mitochondrial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(26):9639–9644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401203111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Howerton CL., Morgan CP., Fischer DB., Bale TL. O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) as a placental biomarker of maternal stress and reprogramming of CNS gene transcription in development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(13):5169–5174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300065110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bouret SG. Early life origins of obesity: role of hypothalamic programming. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(suppl 1):S31–S38. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181977375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bouret SG., Draper SJ., Simerly RB. Formation of projection pathways from the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus to hypothalamic regions implicated in the neural control of feeding behavior in mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(11):2797–2805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5369-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Croizier S., Prevot V., Bouret SG. Leptin controls parasympathetic wiring of the pancreas during embryonic life. Cell Rep. 2016;15(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Smith JT., Waddell BJ. Developmental changes in plasma leptin and hypothalamic leptin receptor expression in the rat: peripubertal changes and the emergence of sex differences. J Endocrinol. 2003;176(3):313–319. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1760313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Yura S., Itoh H., Sagawa N., et al Role of premature leptin surge in obesity resulting from intrauterine undernutrition. Cell Metab. 2005;1(6):371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Attig L., Solomon G., Ferezou J., et al Early postnatal leptin blockage leads to a long-term leptin resistance and susceptibility to diet-induced obesity in rats. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(7):1153–1160. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Shin BC., Dai Y., Thamotharan M., Gibson LC., Devaskar SU. Pre- and postnatal calorie restriction perturbs early hypothalamic neuropeptide and energy balance. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90(6):1169–1182. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Mela V., Diaz F., Lopez-Rodriguez AB., et al Blockage of the neonatal leptin surge affects the gene expression of growth factors, glial proteins, and neuropeptides involved in the control of metabolism and reproduction in peripubertal male and female rats. Endocrinology. 2015;156(7):2571–2581. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Maccari S., Darnaudery M., Morley-Fletcher S., Zuena AR., Cinque C., Van Reeth O. Prenatal stress and long-term consequences: implications of glucocorticoid hormones. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27(1-2):119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Takahashi LK., Kalin NH. Early developmental and temporal characteristics of stress-induced secretion of pituitary-adrenal hormones in prenatally stressed rat pups. Brain Res. 1991;558(1):75–78. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Henry C., Kabbaj M., Simon H., Le Moal M., Maccari S. Prenatal stress increases the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis response in young and adult rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6(3):341–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Shoener JA., Baig R., Page KC. Prenatal exposure to dexamethasone alters hippocampal drive on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in adult male rats. Am J Physiol Regul integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290(5):R1366–R1373. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00757.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Richardson HN., Zorrilla EP., Mandyam CD., Rivier CL. Exposure to repetitive versus varied stress during prenatal development generates two distinct anxiogenic and neuroendocrine profiles in adulthood. Endocrinology. 2006;147(5):2506–2517. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.McCormick CM., Smythe JW., Sharma S., Meaney MJ. Sex-specific effects of prenatal stress on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress and brain glucocorticoid receptor density in adult rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1995;84(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00153-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Bhatnagar S., Lee TM., Vining C. Prenatal stress differentially affects habituation of corticosterone responses to repeated stress in adult male and female rats. Horm Behav. 2005;47(4):430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Tobe I., Ishida Y., Tanaka M., Endoh H., Fujioka T., Nakamura S. Effects of repeated maternal stress on FOS expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of fetal rats. Neuroscience. 2005;134(2):387. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Hiroi R., Carbone DL., Zuloaga DG., Bimonte-Nelson HA., Handa RJ. Sex-dependent programming effects of prenatal glucocorticoid treatment on the developing serotonin system and stress-related behaviors in adulthood. Neuroscience. 2016;320:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Brunton PJ., Donadio MV., Yao ST., et al 5α-Reduced neurosteroids sex-dependently reverse central prenatal programming of neuroendocrine stress responses in rats. J Neurosci. 2015;35(2):666–677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5104-13.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]