Abstract

Background and Objectives:

The possible association between psoriasis and celiac disease (CD) has long been observed, but epidemiologic studies attempting to characterize this association have yielded inconclusive results. This meta-analysis was conducted with the aims to summarize all available data.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies that reported relative risk, hazard ratio, odds ratio (OR), or standardized incidence ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI) comparing the risk of CD in patients with psoriasis versus participants without psoriasis. Pooled risk ratio and 95% CI were calculated using random-effect, generic inverse-variance methods of DerSimonian and Laird.

Results:

Four retrospective cohort studies with 12,912 cases of psoriasis and 24,739 comparators were included in this meta-analysis. The pooled analysis demonstrated a significantly higher risk of CD among patients with psoriasis compared with participants without psoriasis with the pooled OR of 3.09 (95% CI, 1.92–4.97).

Limitations:

Most primary studies reported unadjusted estimated effect, raising a concern over confounders.

Conclusions:

Our meta-analysis demonstrated an approximately 3-fold increased risk of CD among patients with psoriasis.

Keywords: Celiac disease, epidemiology, psoriasis, risk factor

What was known?

Psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of several comorbidities, but the data on celiac disease are inconclusive.

Introduction

Psoriasis is one of the most common immune-mediated skin disorders with an estimated prevalence of 2%–4% in the adult population.[1] Hyperproliferation of keratinocyte is the pathological hallmark of the disease. Psoriasis is known to be associated with an increased risk of several comorbidities including inflammatory arthritis, metabolic syndrome, and atherosclerotic disease.[2,3,4] The etiology of this autoimmune disorder is unknown but is believed to be an interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental factors such as smoking, high body mass index, and excessive alcohol consumption.[5,6,7]

The association between psoriasis and enteropathy has been recognized since 1971 when Marks and Shuster[8] reported a small group of patients with severe psoriasis who presented with diarrhea/steatorrhea and were ultimately found to have enteropathy that was characterized by histological changes similar to celiac disease (CD). However, subsequent epidemiologic studies attempting to characterize this association have yielded inconclusive results, primarily because of small sample size.[9,10,11,12] Therefore, to further investigate this possible relationship, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies that compared the risk of CD in patients with psoriasis versus nonpsoriasis participants.

Methods

Search strategy

The first two investigators independently searched published articles indexed in MEDLINE and EMBASE database from inception to March 2016 using the search strategy that comprised the terms for psoriasis and CD as described in Supplementary Data 1 (296.6KB, tif) . References of included studies and selected review articles were also manually searched.

Search strategy

Inclusion criteria

The eligibility criteria included the following: (1) Cohort study, cross-sectional study, or case–control study reporting risk of CD among patients with psoriasis compared with participants without psoriasis; (2) relative risk, hazard ratio, incidence ratio (IR), or standardized IR with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or sufficient data to calculate those ratios were provided.

Study eligibility was independently assessed by the two aforementioned investigators. The search and literature review process were overseen by the senior investigator who resolved any different decisions between the first two investigators. Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to evaluate the quality of the included studies.[13] This scale assessed each study in three domains including the recruitment of cases and comparators, the comparability between the cohorts and the ascertainment of the outcomes of interest for a cohort study, and the ascertainment of exposure of interest for case–control study.

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used to extract the following information: First author's name, title of the study, year of publication, year of study, country of origin, study design, study population, method used to identify cases and comparators, method used to diagnose psoriasis and CD, number of participants, and demographic data of participants and confounders that were adjusted and adjusted effect estimates with 95% CI.

This data extraction was independently performed by all investigators. Any discrepancy was resolved by referring back to the original articles.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3 software from the Cochrane Collaboration (London, United Kingdom). We pooled the point estimates from each study using the generic inverse-variance method of DerSimonian and Laird which assigned a weight for each study based on its variance.[14] In light of the high likelihood of between-study variance, we used a random effect model rather than a fixed effect model. Cochran's Q test, which is complemented with the I2 statistic, was used to assess statistical heterogeneity. This I2 statistic quantifies the proportion of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. A value of I2 of 0%–25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, >25% but ≤50% low heterogeneity, >50% but ≤75% moderate heterogeneity, and >75% high heterogeneity.[15]

Results

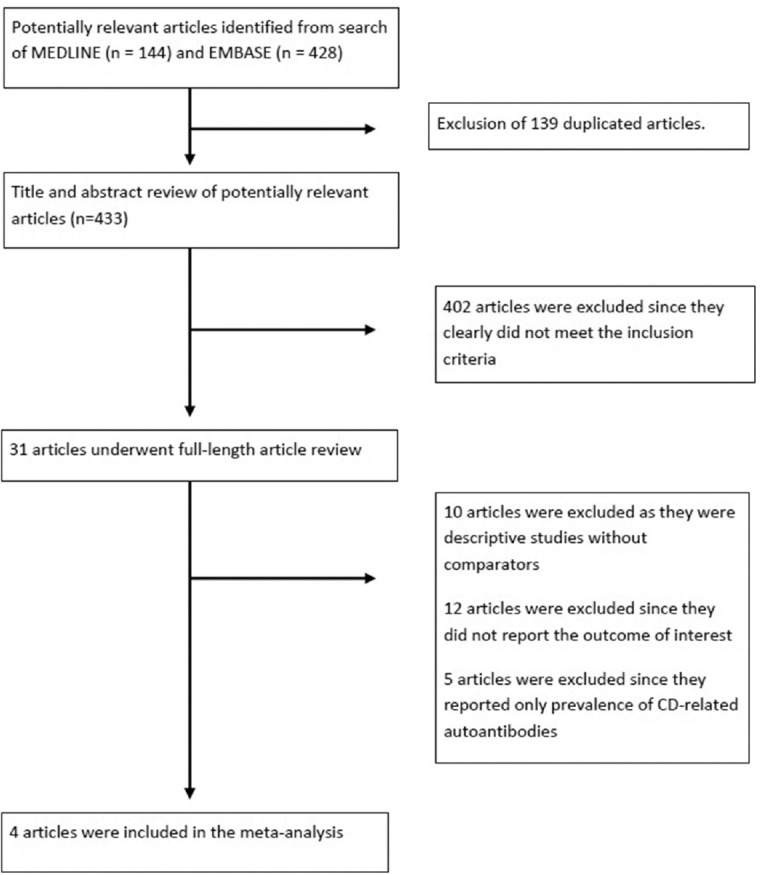

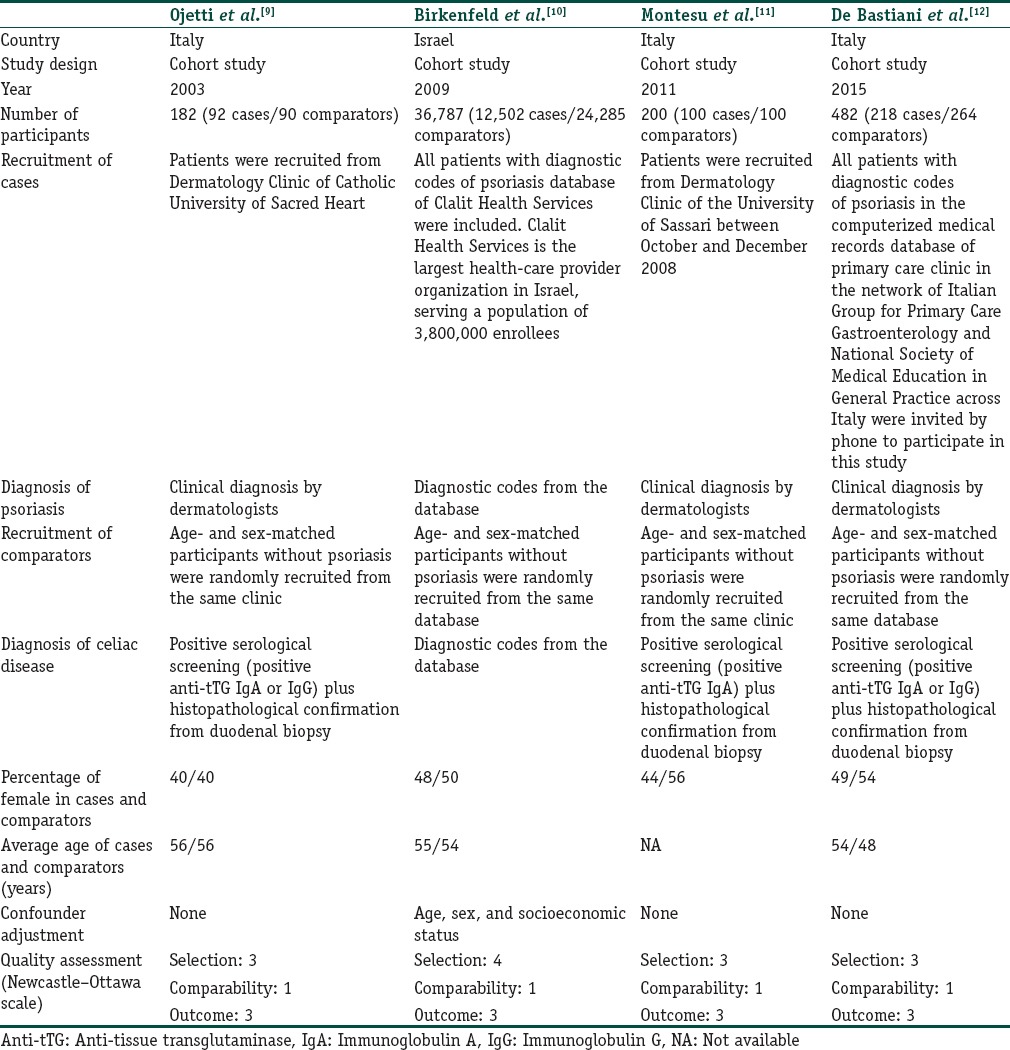

Our search strategy yielded 572 potentially relevant articles (428 articles from EMBASE and 144 articles from MEDLINE). After exclusion of 139 duplicated articles, 433 articles underwent title and abstract review. Four hundred and two articles were excluded at this stage since they were not observational studies, did not report the outcome of interest, or were not conducted in patients with psoriasis, leaving 31 articles for full-length article review. Twelve articles were excluded since they did not report the outcome of interest. Ten studies were excluded as they were descriptive studies without comparators, whereas five of them were excluded since they compared the prevalence of CD-related antibodies between those with and without psoriasis but did not compare the prevalence of clinical disease. Four retrospective cohort studies with 12,912 cases of psoriasis and 24,739 comparators met our inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis.[9,10,11,12] Figure 1 outlines our study identification and literature review process. The clinical characteristics and Newcastle–Ottawa scales of the studies included in this meta-analysis are described in Table 1. It should be noted that the inter-rater agreement for the quality assessment was high with the kappa statistics of 0.66.

Figure 1.

Search methodology and literature review process

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis of the association between psoriasis and celiac disease

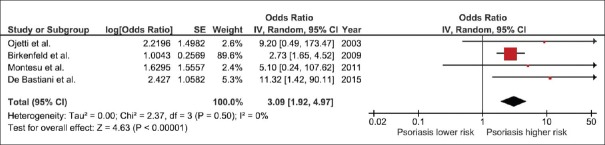

All included studies revealed an increased risk of CD among patients with psoriasis even though did not always reach the statistical significance. The pooled analysis demonstrated a significantly higher risk of CD among patients with psoriasis compared with participants without psoriasis with the pooled odds ratio of 3.09 (95% CI, 1.92–4.97). The statistical heterogeneity was insignificant with an I2 of 0%. The forest plot of this meta-analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of this meta-analysis

To confirm the robustness of our analysis, we performed Jackknife sensitivity analysis by excluding one study at a time from the pooled analysis. The results of this sensitivity analysis ranged from 2.87 to 8.90 and remained statistically significant.

Evaluation for publication bias

Since only four studies were included in this meta-analysis, evaluation for publication bias was not performed.

Discussion

This study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the risk of CD among patients with psoriasis using comprehensive data from all available studies. We were able to demonstrate a statistically significant increased risk of incident atrial fibrillation among patients with psoriasis with approximately 3-fold increased risk of CD compared with participants without psoriasis.

The pathophysiologic mechanisms behind this increased risk are not known, and further investigations are required. However, there are few possible explanations.

First, the association between CD and several autoimmune diseases, such as type I diabetes mellitus and autoimmune thyroid disease, is well documented.[16,17] It is believed that shared genes (at-risk human leukocyte antigen [HLA] haplotypes) might be responsible for this association. For example, type I diabetes mellitus and CD share multiple common genetic loci such as HLA-DR3, HLA-DQ2, and HLA-DQ8.[18] The shared genes might play a similar role in the association between psoriasis and CD.

Second, the hyperproliferated keratinocytes found in patients with psoriasis are known to produce an excessive amount of interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-18, the essential signals for the induction of Th1 response. Interestingly, mucosal inflammation in patients with CD is also caused by activation of Th1 in response to dietary gluten.[9] Therefore, it is possible that those ILs might predispose patients to CD.

Third, it is also possible that, in fact, CD increases the risk of psoriasis, but diagnosis of CD is often delayed or missed as its clinical manifestation could be subtle and nonspecific. Intestinal barrier dysfunction associated with undiagnosed or untreated CD may allow increased passage of immune triggers resulting in increased risk of autoimmune diseases including psoriasis.[10,19]

Our findings may also have implication on the management of psoriasis. Given the possible mechanistic links between the two diseases, gluten-free diet, the cornerstone for the management of CD, may also have a role in the management of psoriasis. In fact, benefit of gluten-free diet among patients with psoriasis has been observed in nonrandomized studies.[20]

The major strength of this study was the advantage of systemic review and meta-analysis that comprehensively combined all available data. All of the included studies were of high quality as reflected in high Newcastle–Ottawa scores. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the study has some limitations and the results should be interpreted with caution.

First, most of the included studies reported an unadjusted estimated effect. Therefore, confounders could play a role in this apparent association. Second, we could not perform an evaluation for publication bias as only four studies were included in the analysis. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of publication bias in favor of positive studies. Third, the primary studies were conducted in only two countries which might limit the generalizability of our results to other populations.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis demonstrated an approximately 3-fold increased risk of CD among patients with psoriasis. Whether routine screening for CD is suggested in clinical practice requires further investigations.

Level of evidence for this study

Level II-2.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Patients with psoriasis are at approximately 3-fold increased risk of celiac disease compared with participants without psoriasis.

References

- 1.Christophers E. Psoriasis – Epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:314–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Jørgensen CH, Lindhardsen J, Charlot M, Olesen JB, et al. Psoriasis and risk of atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2054–64. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kokpol C, Aekplakorn W, Rajatanavin N. Prevalence and characteristics of metabolic syndrome in South-East Asian psoriatic patients: A case-control study. J Dermatol. 2014;41:898–902. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ungprasert P, Sanguankeo A, Upala S, Suksaranjit P. Psoriasis and risk of venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM. 2014;107:793–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcu073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, Armstrong EJ. Psoriasis and smoking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:304–14. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy DL, Spelman LS, Martin NG. Psoriasis in Australian twins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:428–34. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Correia B, Torres T. Obesity: A key component of psoriasis. Acta Biomed. 2015;86:121–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks J, Shuster S. Psoriatic enteropathy. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:676–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojetti V, Aguilar Sanchez J, Guerriero C, Fossati B, Capizzi R, De Simone C, et al. High prevalence of celiac disease in psoriasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2574–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birkenfeld S, Dreiher J, Weitzman D, Cohen AD. Coeliac disease associated with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1331–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montesu MA, Dessì-Fulgheri C, Pattaro C, Ventura V, Satta R, Cottoni F. Association between psoriasis and coeliac disease? A case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:92–3. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Bastiani R, Gabrielli M, Lora L, Napoli L, Tosetti C, Pirrotta E, et al. Association between coeliac disease and psoriasis: Italian primary care multicentre study. Dermatology. 2015;230:156–60. doi: 10.1159/000369615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Counsell CE, Taha A, Ruddell WS. Coeliac disease and autoimmune thyroid disease. Gut. 1994;35:844–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.6.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuppan D, Hahn EG. Celiac disease and its link to type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14(Suppl 1):597–605. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2001.14.s1.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth DJ, Plagnol V, Walker NM, Cooper JD, Downes K, Yang JH, et al. Shared and distinct genetic variants in type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2767–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ventura A, Magazzù G, Greco L. Duration of exposure to gluten and risk for autoimmune disorders in patients with celiac disease. SIGEP study group for autoimmune disorders in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:297–303. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatia BK, Millsop JW, Debbaneh M, Koo J, Linos E, Liao W. Diet and psoriasis, part II: Celiac disease and role of a gluten-free diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:350–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy