Abstract

Background:

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an immunoglobulin G-mediated autoimmune bullous skin disease. Nonorgan-specific antibodies were detected in Tunisian and Brazilian pemphigus patients with different prevalence.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty PV patients and fifty controls were screened for antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMAs), anti-parietal antibodies (APAs), anti-mitochondrial antibodies, and Anti-nuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) by indirect immunofluorescence.

Results:

Thirty-nine patients were female and 11 were male. Fifteen patients did not receive treatment before while 35 patients were on systemic steroid treatment ± azathioprine. Twenty (40%) of the PV patients and 1 (2%) control had positive ANA. ANA was significantly higher in PV patients than controls, P < 0.0001. ASMAs were detected in 20 (40%) PV patients and none of the controls. ASMA was significantly higher in PV patients than controls, P < 0.0001. No significant difference was detected between treated and untreated regarding ANA, P - 0.11. However, there was a significant difference between treated and untreated regarding ASMA, P - 0.03. Six patients (12%) and none of the controls had positive APA. There was a significant difference between the patients and the controls in APA. P - 0.027.

Conclusion:

Egyptian PV patients showed more prevalent ANA, ASMA, and APA than normal controls. Follow-up of those patients is essential to detect the early development of concomitant autoimmune disease. Environmental factors might account for the variability of the nonorgan-specific antibodies among different populations.

Keywords: Anti-mitochondrial antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-parietal antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies, autoantibodies, autoimmune bullous diseases, pemphigus vulgaris

What was known?

Serum antibodies are the diagnostic biomarkers for autoimmune diseases. Nonorgan-specific autoantibodies were detected in Brazilian and Tunisian pemphigus patients.

Introduction

Pemphigus is an immunoglobulin G-mediated autoimmune bullous disease targeting the interkeratinocyte adhesion molecules, desmogleins.[1] Pemphigus is more common in certain populations, for example, people of the Mediterranean area.[2] The incidence of pemphigus in Turkey was 0.24/100,000/year.[2] Moreover, the incidence of pemphigus in Bulgaria was 0.47/100,000/year.[3] On the other hand, the disease is endemic in Brazil[4] and Tunisia.[5] The incidence of pemphigus in Tunisia was 0.67/100,000/year.[6] Genetic and environmental factors account for higher predisposition in certain ethnic groups.

Serum antibodies are the diagnostic biomarkers for autoimmune diseases. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) is associated with many autoimmune diseases,[7] for example, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura,[7] and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).[8] Moreover, ANA is produced in response to some infections.[7,9] ANA was detected in 0%–2.5% Brazilian endemic pemphigus foliaceus (PF).[10,11] Moreover, it was detected in 5.7% of Tunisian PF and 13.7% of Tunisian pemphigus vulgaris (PV) patients.[12]

Anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMAs) are important antibodies for diagnosing AIH.[8] ASMA were detected in 0.8% of Brazilian PF,[10] 2.8% of Tunisian PF, and 5.8% of Tunisian PV patients.[12] Anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMAs) can be detected in 90% of primary biliary cirrhosis patients, 5% AIH patients and hepatitis C patients.[13] AMA was not detected in any Brazilian PF[10] and was detected in 2.8% Tunisian PF and 7.8% Tunisian PV patients.[12]

Anti-parietal antibodies (APAs) are the main autoantibodies in autoimmune atrophic gastritis and pernicious anemia. On the other hand, it can be detected in primary liver cirrhosis.[14] APA was detected in 1% Tunisian PV[12] and 0% Brazilian PF.[10]

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are sensitive markers for vasculitis. ANCA-C is usually associated with Wegner's granulomatosis, while ANCA-P is usually associated with microscopic polyangiitis.[15] ANCA was detected in 2.8% Tunisian PF and 3.8% Tunisian PV patients.[12] ANCA was not detected in Brazilian PF patients.[11]

In this work, we tried to detect whether Egyptian PV patients possess autoantibodies other than anti-desmogleins.

Materials and Methods

In the present study, fifty patients who fulfilled the clinical, pathological, and immunofluorescence criteria of PV were included. Fifty volunteers coming for check-up served as controls. We excluded individuals who were infected with hepatitis B or hepatitis C viruses. Patients were subjected to history taking, clinical examination, abdominal ultrasound, and chest X-ray. Moreover, the reactivity of the patients’ sera against human desmoglein 3 was measured by desmoglein 3 ELISA and was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antihuman IgG according to the manufacturer's instructions (EUROIMMUN, Lubeck, Germany). Blood samples were withdrawn from the patients and the controls for complete blood pictures, liver and kidney function tests, fasting, and 2 h postprandial glucose level. Sera collected from patients and controls were screened by indirect immunofluorescence for ANA, ASMA, AMA, APA (EUROIMMUN, Lubeck, Germany), and ANCA (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA). Samples were diluted into 1:100 and tests were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The same investigations were repeated for ten patients after 1 year of treatment. Moreover, investigations were done for the follow-up patients in the form of hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis C RNA was measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The collected data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2007 and GraphPad Prism 5 for Windows (San Diego, California, USA). Continuous quantitative data were described in terms of range, mean, and standard deviation when parametric tests are appropriate or median when nonparametric tests are appropriate. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Dermatology Department and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

Results

In the PV patients, 39 were female and 11 were male. Their age ranged from 20 to 70 years. The desmoglein 3 index ranged from 0.9 to 660. None of the patients had known associated autoimmune disease. None of the patients showed any clinical sign of systemic lupus erythematosus, AIH, primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune atrophic gastritis, or pernicious anemia. Fifteen patients did not receive treatment before while 35 patients were on systemic steroid treatment ± azathioprine. Complete blood picture, renal, liver function tests, and blood glucose level were normal for all the controls. Complete blood picture, renal functions tests, blood glucose level, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and abdominal ultrasound were normal for all the patients. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was mildly elevated in 15 patients (range, 42–55 U/L). Normal ALT was up to 41 U/L. Two patients had low albumin levels (range, 2–3 g/dL). Normal albumin ranged from 3.5 to 5 g/dL.

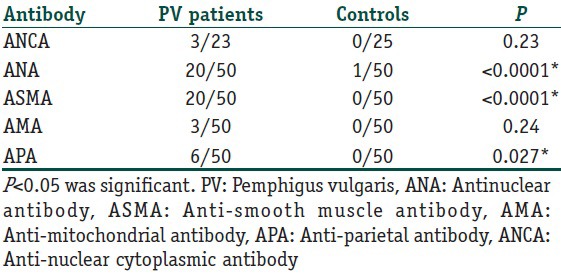

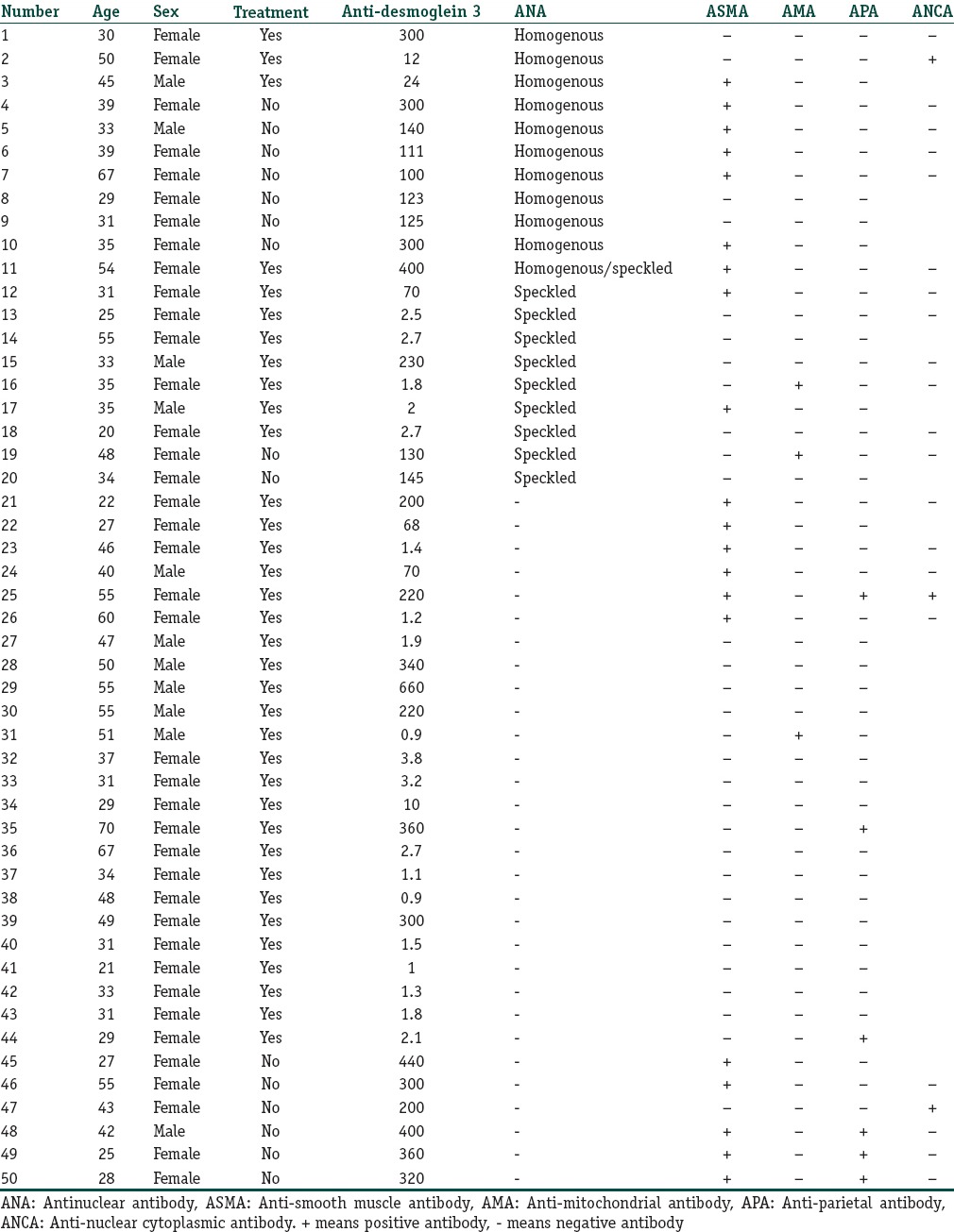

Twenty (40%) PV patients and 1 (2%) control had positive ANA [Table 1]. ANA was significantly higher in PV patients than controls, P < 0.0001. Of the 20 PV patients, 16 were female, 4 were male, 9 did not receive treatment before while 11 were on systemic steroids and azathioprine. The pattern of ANA was homogenous in ten patients, speckled in nine patients, and mixed speckled and homogenous in one patient [Table 2]. No significant correlation was found between desmoglein 3 ELISA and ANA pattern.

Table 1.

Autoantibodies in pemphigus vulgaris patients

Table 2.

Summary of the autoimmune profile of the patients

ASMA was detected in 20 (40%) PV patients. ASMA was significantly higher in PV patients than controls, P < 0.0001. Of the twenty patients, ten did not receive treatment before [Table 2]. Nine (18%) PV patients had both ANA and ASMA.

No significant difference was detected between treated and untreated regarding ANA, P - 0.11. However, there was a significant difference between treated and untreated regarding ASMA, P - 0.03.

Three PV patients showed positive AMA. There was no significant difference between patients and controls in the AMA, P - 0.2. Twenty-three patients and 25 controls were screened for ANCA-P and ANCA-C antibodies. Three out of 23 (13%) PV patients and none of the controls had ANCA-C. There was no significant difference between patients and controls regarding ANCA-C, P - 0.1.

Six patients (12%) and none of the controls had positive APA. There was a significant difference between the patients and the controls in APA, P - 0.027. There was no significant difference between treated and not treated regarding APA, P - 0.3.

Ten patients were followed up after 1 year of systemic steroids and azathioprine treatment. Four of those patients developed ASMA after 1 year of therapy. On further investigations, anti-hepatitis C antibody was positive and hepatitis C RNA was detected by PCR in those patients.

Discussion

PV is a tissue-specific autoimmune skin disease. Although anti-desmogleins are the main autoantibodies defining this disease, few reports showed the presence of other autoantibodies in pemphigus patients.[11,12] However, there is variability of the prevalence of those antibodies among different populations. In this work, we screened PV patients for ANA, ASMA, APA, AMA, and ANCA, and we compared our results to the available literature of Tunisian[12] and Brazilian populations.[10,11] We excluded hepatitis patients because of the frequent presence of nonorgan-specific antibodies in them.[9,16,17]

Although the incidence of pemphigus in the Egyptian population is not known yet, PV is the most common autoimmune bullous disease in Egypt.

Our results showed that Egyptian PV patients showed more prevalent ANA, ASMA, and APA than normal controls. Moreover, Egyptian PV patients showed more prevalent ANA, ASMA, and APA than Tunisian[12] and Brazilian patients.[10] Since environmental factors played an important role in the development of ANA among normal individuals.[18] Therefore, one can conclude that the environmental variations between Egypt, Tunisia, and Brazil accounted for the difference in the prevalence of nonorgan-specific antibodies. Environmental factors that were linked to autoimmune diseases included diet, smoking, drugs, industrial compounds, and chemicals.[19]

The presence of nonorgan-specific antibodies in PV patients could be a form of epitope spreading phenomena. On the other hand, molecular mimicry between environmental infectious agents and self-antigens could be the mechanism that triggered this whole autoimmune process.[20]

Our results showed that ANA was detected in 40% of Egyptian PV patients compared to 5.7% Tunisian PF patients, 13.7% Tunisian PV,[12] and 0%–2.5% Brazilian PF.[10,11] Contrary to Tunisians in whom the pattern of the ANA was speckled in the majority of patients,[12] the pattern was homogenous (50%) and speckled (50%) in the Egyptians. Homogenous pattern reflected antibodies to histones, double-stranded DNA, or chromatin. On the other hand, speckled pattern reflected antibodies to non-DNA nuclear antigens.[21]

ASMA was detected in 40% of Egyptian PV patients compared to 0.8% of Brazilian PF,[10] 2.8% of Tunisian PF, and 5.8% of Tunisian PV patients.[12] Interestingly, nine (18%) PV patients had both ANA and ASMA. Although ANA and ASMA are classic markers for AIH, the patients did not show any clinical sign of AIH.[8] However, we could not exclude asymptomatic AIH as we did not do liver biopsy which is essential for diagnosing this condition.[22] Our data showed a significant difference between treated and untreated regarding ASMA, P - 0.03. Therefore, one can conclude that treatment could be masking the positivity of the ASMA. The development of ASMA in 4 patients who later proved to have hepatitis C after 1 year of therapy is suggestive that ASMA could be a marker of hepatitis C infections.

AMA was not detected in any Brazilian PF[10] and was detected in 2.8% Tunisian PF and 7.8% Tunisian PV patients.[12] In accordance with the Tunisians, AMA was detected in 6% of our PV patients. APA was detected in 1% Tunisian PV[12] and 0% Brazilian PF.[10] Our results showed a higher prevalence of APA (12%) among Egyptian PV patients.

Conclusion

Egyptian PV patients showed more prevalent ANA, ASMA, and APA than normal controls. Follow-up of those patients is essential to detect the early development of concomitant autoimmune disease. Environmental factors might account for the variability of the nonorgan-specific antibodies among different populations. More efforts are needed to determine the impact of environmental factors on PV.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Egyptian pemphigus vulgaris patients showed more prevalent antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, and anti-parietal antibody than normal controls. Moreover, Egyptian pemphigus vulgaris patients showed more prevalent antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, and anti-parietal antibody than Tunisian and Brazilian patients.

References

- 1.Kárpáti S, Amagai M, Prussick R, Cehrs K, Stanley JR. Pemphigus vulgaris antigen, a desmoglein type of cadherin, is localized within keratinocyte desmosomes. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:409–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.2.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uzun S, Durdu M, Akman A, Gunasti S, Uslular C, Memisoglu HR, et al. Pemphigus in the Mediterranean region of Turkey: A study of 148 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:523–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsankov N, Vassileva S, Kamarashev J, Kazandjieva J, Kuzeva V. Epidemiology of pemphigus in Sofia, Bulgaria. A 16-year retrospective study (1980-1995) Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:104–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki V, Rivitti EA, Diaz LA. Cooperative Group on Fogo Selvagem Research. Update on fogo selvagem, an endemic form of pemphigus foliaceus. J Dermatol. 2015;42:18–26. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morini JP, Jomaa B, Gorgi Y, Saguem MH, Nouira R, Roujeau JC, et al. Pemphigus foliaceus in young women. An endemic focus in the Sousse area of Tunisia. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:69–73. doi: 10.1001/archderm.129.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastuji-Garin S, Souissi R, Blum L, Turki H, Nouira R, Jomaa B, et al. Comparative epidemiology of pemphigus in Tunisia and France: Unusual incidence of pemphigus foliaceus in young Tunisian women. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:302–5. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12612836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabiedes J, Núñez-Álvarez CA. Antinuclear antibodies. Reumatol Clin. 2010;6:224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancado EL, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Terrabuio DR. The importance of autoantibody detection in autoimmune hepatitis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:222. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berlin T, Zandman-Goddard G, Blank M, Matthias T, Pfeiffer S, Weis I, et al. Autoantibodies in nonautoimmune individuals during infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1108:584–93. doi: 10.1196/annals.1422.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nisihara RM, de Bem RS, Hausberger R, Roxo VS, Pavoni DP, Petzl-Erler ML, et al. Prevalence of autoantibodies in patients with endemic pemphigus foliaceus (Fogo selvagem) Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295:133–7. doi: 10.1007/s00403-003-0412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Squiquera HL, Diaz LA, Sampaio SA, Rivitti EA, Martins CR, Cunha PR, et al. Serologic abnormalities in patients with endemic pemphigus foliaceus (Fogo selvagem), their relatives, and normal donors from endemic and non-endemic areas of Brazil. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:189–91. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12464490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mejri K, Abida O, Kallel-Sellami M, Haddouk S, Laadhar L, Zarraa IR, et al. Spectrum of autoantibodies other than anti-desmoglein in pemphigus patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:774–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cancado EL, Harriz M. The importance of autoantibody detection in primary biliary cirrhosis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:309. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liaskos C, Norman GL, Moulas A, Garagounis A, Goulis I, Rigopoulou EI, et al. Prevalence of gastric parietal cell antibodies and intrinsic factor antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:411–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radice A, Sinico RA. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) Autoimmunity. 2005;38:93–103. doi: 10.1080/08916930400022673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroffolini T, Colloredo G, Gaeta GB, Sonzogni A, Angeletti S, Marignani M, et al. Does an ‘autoimmune’ profile affect the clinical profile of chronic hepatitis C? An Italian multicentre survey. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:257–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khairy M, El-Raziky M, El-Akel W, Abdelbary MS, Khatab H, El-Kholy B, et al. Serum autoantibodies positivity prevalence in patients with chronic HCV and impact on pegylated interferon and ribavirin treatment response. Liver Int. 2013;33:1504–9. doi: 10.1111/liv.12227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper GS, Parks CG, Schur PS, Fraser PA. Occupational and environmental associations with antinuclear antibodies in a general population sample. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2006;69:2063–9. doi: 10.1080/15287390600746165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt CW. Questions persist: Environmental factors in autoimmune disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:A249–53. doi: 10.1289/ehp.119-a248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cusick MF, Libbey JE, Fujinami RS. Molecular mimicry as a mechanism of autoimmune disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;42:102–11. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8294-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh M, Vázquez-Del Mercado M, Chan EK. Clinical interpretation of antinuclear antibody tests in systemic rheumatic diseases. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:219–28. doi: 10.1007/s10165-009-0155-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kogan J, Safadi R, Ashur Y, Shouval D, Ilan Y. Prognosis of symptomatic versus asymptomatic autoimmune hepatitis: A study of 68 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:75–81. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]