Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) harbors the worst prognosis of any common solid tumor, and multiple failed clinical trials indicate therapeutic recalcitrance. Here we use exome sequencing of patient tumors and find multiple conserved genetic alterations. However, the majority of tumors exhibit no clearly defined therapeutic target. High-throughput drug screens using patient-derived cell lines found rare examples of sensitivity to monotherapy, with most requiring combination therapy. Using PDX models, we confirmed the effectiveness and selectivity of the identified treatment responses. Out of greater than 500 single and combination drug regimens tested, no single treatment was effective for the majority of PDAC tumors, and each case had unique sensitivity profiles that could not be predicted using genetic analyses. These data indicate a shortcoming of reliance on genetic analysis to predict efficacy of currently available agents against PDAC, and that sensitivity profiling of patient-derived models could inform personalized therapy design for PDAC.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

A precision approach to cancer medicine is transforming the way in which cancer is treated (Aronson and Rehm, 2015; Biankin et al., 2015). Conventionally, this approach relies on the use of markers to define a treatment strategy for a given disease. There are multiple successes attributed to precision medicine, from the current paradigm for breast cancer treatment stratification based on immunohistochemical markers (e.g. ER,PR or HER2) to the integrated genetic analysis of lung cancer that reveals multiple targets for therapeutic intervention (e.g., ALK rearrangements or EGFR mutations) (Deluche et al., 2015; Lindeman et al., 2013). Based on these and other successes, multiple clinical trials utilizing genetic information to guide patient treatment are open.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) harbors a particularly poor prognosis, and even in the case of resected disease, long-term survival remains poor due to the frequent recurrence as metastatic disease (Almhanna and Philip; Kleger et al., 2014; Paulson et al., 2013; Yeo et al., 1995). Current systemic treatment of PDAC is dependent on chemotherapy, with minimal success of targeted approaches in the clinic. This therapeutic recalcitrance of PDAC is surprising given substantial pre-clinical investigation, and multiple provocative findings that would be expected to yield clinical benefit. This disconnect between preclinical testing and clinical outcomes suggests that more relevant models will be important for making significant inroads into the treatment of PDAC and that some form of patient stratification will be required to yield improved outcome. Notably, exceptional responses to therapy do occur in patients with pancreatic cancer (Garrido-Laguna et al., 2015), but these represent a very small segment of the treated population.

To date, pancreatic cancer has largely failed to benefit from the promise of precision therapy. In spite of substantial genetic analyses (Bailey et al., 2016; Collisson et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2008; Waddell et al., 2015; Witkiewicz et al., 2015), the path for the treatment of the majority of PDAC cases remains obscure. Pancreatic cancer is driven by KRAS which is currently considered a non-actionable target. Additionally, most pancreatic tumors harbor genetic lesions in multiple oncogenic pathways (e.g. MYC amplification) or tumor suppressive pathways (e.g. SMAD4 loss) that make it unclear how targeting a single genetic event would yield therapeutic benefit. Thus, the nature and complexity of tumor genetics in pancreatic cancer represent the major impediments to precision treatment.

Here, we employ an integrated collection of patient-derived cell lines and xenografts that recapitulate the genetics and biology of PDAC to identify and validate patient-selective therapeutic sensitivities. This approach bypasses the bottleneck of requiring genetic targets for therapeutic intervention and revealed multiple unique combinatorial approaches to target individual tumors.

Results

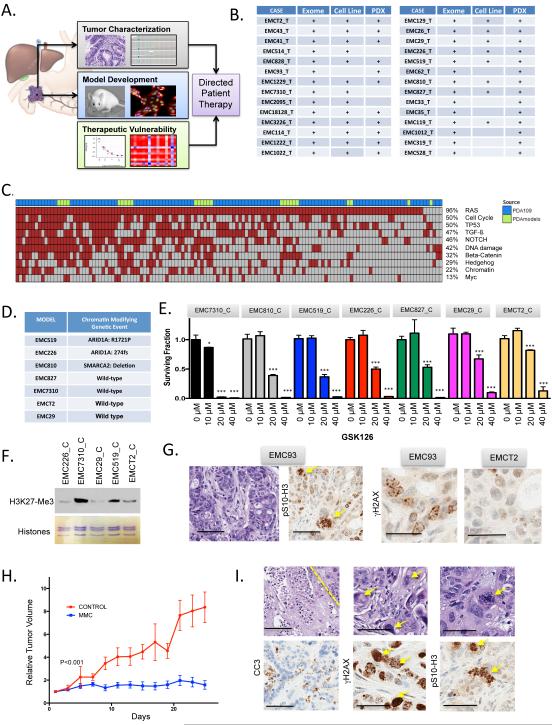

Pipeline for genetic and functional analysis

A pipeline was developed wherein patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) consented to the collection of tumor tissue, genetic studies and development of models (Fig 1A and B). Primary tumors, patient-derived cell lines, and PDX models were characterized by exome sequencing and exhibited a high level of genetic conservation with the primary tumor and recapitulated key features of disease (Knudsen et al. submitted). Cell models were employed to define therapeutic sensitivities and selected treatments were subsequently validated in the context of the PDX originating from same primary tumor. From the genetic analysis, greater than 1000 tumor specific genetic events were identified, many of which impacted on cancer relevant pathways that are known to be disrupted in PDAC (Fig 1C).

Figure 1. Genetic interrogation of PDAC models.

(A) Schematic of the overall pipeline employed. Tumor tissue not required for diagnosis was used for characterization of the patient tumor. Parallel tissue was employed for development of PDX and cell line models. Models were utilized to evaluate drug sensitivities that could then inform genetic or empirically defined sensitivities. (B) Summary of the models generated from PDAC cases as employed in the study. (C) Overall distribution of genetic events targeting oncogenic pathways in PDAC cases employed in this study (green color bar), relative to 109 cases that have previously been published. (D) Summary of models harboring the indicated genetic alterations in chromatin modifiers. (E) The indicated models were treated with increasing dose of GSK126 (0, 10, 20, 40 μM). Data are from greater than 4 independent measures with the mean and standard deviation shown. Data was statistically significant as determined by unpaired t-test, ***p<0.001. (F) The levels of H3K27-Me3 were determined in the indicated models, total histone levels were utilized for loading control. (G) The presence of aberrant mitosis and basal levels of DNA damage were determined by immunohistochemical analysis with pSer10-Histone H3 and γH2AX staining respectively. Representative images are shown. The scale bar for the hematoxylin and pSer10-Histone H3 staining is 100 μm, while the γH2AX staining is 50 μm. The EMC93 case has a mutation in STAG2. (H) The EMC93 PDX was randomized for treatment with either vehicle control (n=4) or mitomycin C (n=7). Tumor volume was determined by calipers as a function of time. Mice were sacrificed when controls became moribund. The difference in tumor volume was statistically significant as determined by ANOVA. (I) Representative images showing confluent necrosis and aberrant nuclei in treated tumors (scale bar is 100 μm). Increased cleaved caspase 3 (scale bar is 100 μm), γH2AX and mitotic aberrations were detected by immunohistochemistry (scale bar is 50 μm).

Patient models can inform genetic-driven therapeutic sensitivity in PDA

A main precept of precision oncology is that genetic analysis of the tumor will inform therapeutic options. However, from mutational events identified in the 28 cases only a handful represented targets for therapeutic intervention. Additionally, many of the potentially actionable alleles represented variants of unknown significance. In this setting, the availability of patient-derived models provided a unique opportunity to assess the impact of a given allele on therapeutic sensitivities.

Chromatin remodeling SWI/SNF complex genes (e.g. ARID1A, PBRM1 and SMARCA4) are mutated in up to 20% of PDAC and recent studies indicated that SWI/SNF deficiency results in sensitivity to EZH2 inhibition (Bitler et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2015). Two cell models exhibited genetic alterations in ARID1A chromatin remodeling gene and one harbored a SMARCA2 deletion (Fig 1D). The models were treated with the EZH2 inhibitors GSK126 and GSK343 and survival was determined (Fig 1E and S1). Surprisingly, the EMC7310 model that was wild-type for chromatin modifiers, was the most sensitive to EZH2 inhibitors, while models harboring mutations in chromatin remodelers had intermediate sensitivities (Fig 1E and S1). This marked sensitivity could be due to the presence of high-levels of H3 K27-Me3 in EMC7310 cell line (Fig 1F) and/or other genetic features of the model (e.g. MYC amplification or RB loss). However, these data underscore the challenge of targeting specific genetic events occurring in complex cancer genomes and the need to functionally assess therapeutic sensitivities.

Another case exhibited mutation of the STAG2 gene on the X-chromosome in the primary tumor and resultant PDX model. This event can compromise mitotic fidelity and elicit sensitivity to DNA cross-linking agents (Evers et al., 2014; Solomon et al., 2011). Consistent with STAG2-deficiency, the PDX exhibited significant nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic aberrations, and high baseline DNA damage relative to other PDX models (Fig 1G). Consequently, treatment with Mitomycin C significantly restricted tumor growth in this model (Fig 1H). This response was marked by extensive DNA damage and evidence of mitotic catastrophe (Fig 1I). Thus, in rare circumstances the genetics of an individual pancreatic tumor could inform treatment.

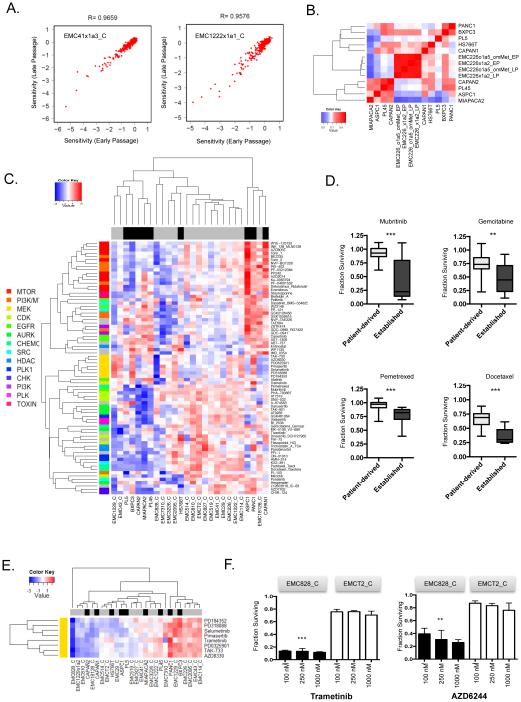

Patient-derived cell lines define selective therapeutic vulnerabilities

The relative low-frequency of clear, genetically encoded vulnerabilities combined with the complexity surrounding many genetic variants makes predicting therapeutic sensitivities in PDAC particularly difficult. In recognition of this challenge, and to define therapeutic vulnerabilities in the majority of tumors that do not harbor actionable genetic events, a drug sensitivity screen with a library of 305 agents (Data Table 1) was employed against the patient-derived cell lines we developed and the established PDAC cell lines. The drug panel included compounds that are in clinical use or advanced development and target multiple aspects of tumor biology (e.g., cell cycle, apoptosis, growth factor signaling pathways). For each cell line, early and late passage cultures were evaluated and showed marked conservation of drug sensitivities (Fig 2A and S2). Cell lines developed directly from the primary tumor or from PDX established from the same primary tumor clustered together, indicating preservation of therapeutic responsiveness across derivative models (Fig 2B). 59 patient-derived cell line models were screened in total at 100 nM-1 μM dose range, and area under the curve (AUC) was calculated per drug per cell line (range 0.08 – 4.95) (Data Table 1). Among the 305 drugs screened, 76 drugs with AUC < 1.5 in at least one model were identified as hits and were clustered based on Euclidian distance (Fig 2C). The data showed that similar targeted agents cluster together, indicating that there are intrinsic sensitivities to specific pathways (e.g., MEK or EGFR inhibition) or chemotherapy. Unsupervised clustering of models and affinity propagative clustering showed that established cancer cell lines had distinct sensitivities compared to primary models (Fig 2C and S2). In general, established models were significantly more sensitive to chemotherapy agents (i.e., gemcitabine, pemetrexed and docetaxel), and one targeted agent (mubritinib) was selectively effective in established cell lines (Fig 2D). Across the panel, patient-derived cell lines exhibited a highly variable response to treatment with selected models markedly inhibited by targeted therapies. For example, one of the tumor models was exceptionally sensitive to multiple MEK inhibitors (Fig 2E and F), while other models had selective sensitivity to EGFR or Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Fig S2).

Figure 2. PDAC cell lines reveal disparate sensitivity to cancer drugs.

(A) Early and late passage cell lines were subjected to drug screening. Regression correlation analysis revealed that the drug sensitivities across passages remained highly correlated. (B) Spearman correlation analysis of multiple cell lines derived from the same model showed that distinct models harbored highly correlated responses to cancer drugs relative to other established pancreatic cancer models. (C) Heatmap of primary cell lines (gray) and established (black) cell lines clustered based on AUC. The agent color-bar is associated with different drug classes as indicated. (D) Drug sensitivities that were statistically different between patient-derived and established lines are noted in box and whisker plots with statistical significance determined by t-test, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01. (E) The AUC of drug response to the indicated MEK inhibitors was used to cluster models based on Euclidian distance. The EMC828 cell line exhibited a unique sensitivity to these agents. (F) Dose response analysis from EMC828 vs. EMCT2 cell line models treated at 100 nM, 250 nM and 1 μM. The mean surviving fraction and standard deviation are shown (n=3). The difference in response between EMC828 and EMCT2 was statistically significant as determined by unpaired t-test, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01.

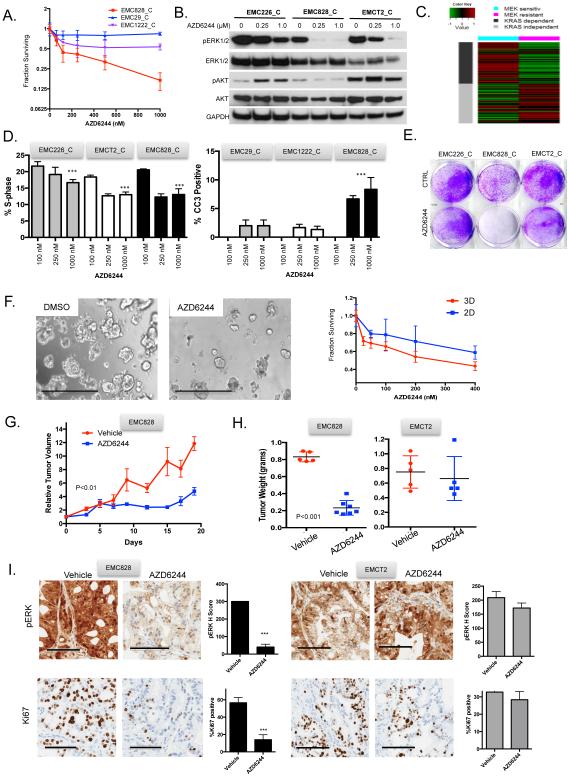

Patient models define exceptional responses to therapeutic agents

Identifying exceptional responses to therapy has become one of the critical approaches to define targeted means to treat PDAC and other therapy recalcitrant diseases. Although MEK inhibitors had limited single-agent antitumor activity in clinical trails conducted in unselected PDAC patients, there has been evidence for exceptional response in patients with metastatic disease (Garrido-Laguna et al., 2015). Through detailed dose response analysis, we found that the EMC828 model was sensitive to low dose MEK inhibition (Fig 3A). In general, resistance to MEK-inhibitors is associated with compensatory activation of AKT signaling (Mirzoeva et al., 2009; Pettazzoni et al., 2015). The exceptional sensitivity to MEK inhibition was associated with a failure to engage the upregulation of AKT, and AKT activity was actually suppressed upon treatment with MEK inhibition in this model (Fig 3B). RNA sequencing revealed that the exceptional response to MEK inhibition associated with an enrichment of genes involved in cell adhesion, epithelial vs mesenchymal differentiation and KRAS dependence signature (Singh et al., 2009). This signature was significantly enriched in the EMC828 model vs. the less sensitive cell lines (Fig 3C). The sensitivity to MEK inhibition was associated with both inhibition of cell cycle progression and the induction of apoptosis that translated into overall suppression of viability in clonal assays and 3-D organoid cultures (Fig 3D-F). Since MEK inhibition typically exerts a cytostatic effect, these data reinforced the concept that this select tumor would be highly sensitive to MEK inhibition. The PDX model developed from the same primary tumor was subjected to treatment with the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 (Fig 3G and H). Treatment resulted in marked suppression of tumor growth. Importantly, this response was selective to the model predicted to be sensitive, as AZD6244 had minimal effect on tumor growth in another PDX (i.e. EMCT2). The response to AZD6244 in vivo was characterized by suppression of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and Ki67 in the sensitive model EMC828, but not the comparator tumor EMCT2 (Fig 3I). Consistent with these data, MEK treatment of xenografts resulted in suppression of RB-phosphorylation and cell cycle regulated proteins as determined by reverse phase protein arrays (Fig S3). Less dramatic single-agent responses observed in cell culture with multiple targeted agents (IMD-0354, ABT-737, and CHIR125) were associated with essentially no therapeutic response in corresponding PDX models (Fig S3). These findings suggest that exceptional responses in cell culture are required in order to have therapeutic impact on PDAC tumors in vivo, and recapitulate the known therapeutic recalcitrance of the disease.

Figure 3. Exceptional response to MEK inhibition.

(A) Dose response analysis of EMC828 vs EMC29 and EMC1222 cell line models exposed to AZD6244. Average and standard deviation are shown from three experiments. (B) Immunoblot analysis of the indicated proteins in the models treated with 0, 0.25 and 1 μM AZD6244. (C) The published KRAS dependence signature was subjected to supervised clustering based on the exceptional response vs. resistance. (D) The suppression of BrdU incorporation and induction of apoptosis was determined for the indicated cell lines with increasing concentrations of AZD6244 (0, 0.25 μM, 1 μM). Mean and standard deviation are shown from three independent experiments, p-value relative to vehicle control was determined by unpaired t-test, ***p<0.001. (E) Representative crystal violet staining for cell viability in the indicated cell lines exposed to AZD6244. (F) Representative micrographs of the EMC828 model grown as an organoid in 3D culture. Images were taken at 4x, scale bar is 1 mm. Cells grown in 3D and 2D from three independent cultures are were subjected to increasing doses of AZD6244 and viability was determined. Mean and standard deviation are shown. (G) The EMC828 xenograft was randomized to treatment with vehicle (n=5) or AZD6244 (n=5) until the control arm became moribund. The mean and standard error of the mean is shown, statistical significance was determined by ANOVA. (H) Tumor weight from the indicated PDX models treated with vehicle or AZD6244 was determined at sacrifice. Statistical analysis was determined by unpaired t-test. (I) Representative immunohistochemical images of pERK1/2 and Ki67. Scale bar is 100 μm. Quantification of the staining, the average and standard deviation from >10 high-power fields are shown. Statistical analysis was by unpaired t-test, ***p<0.001.

Uncovering effective combination therapies by high-throughput screening

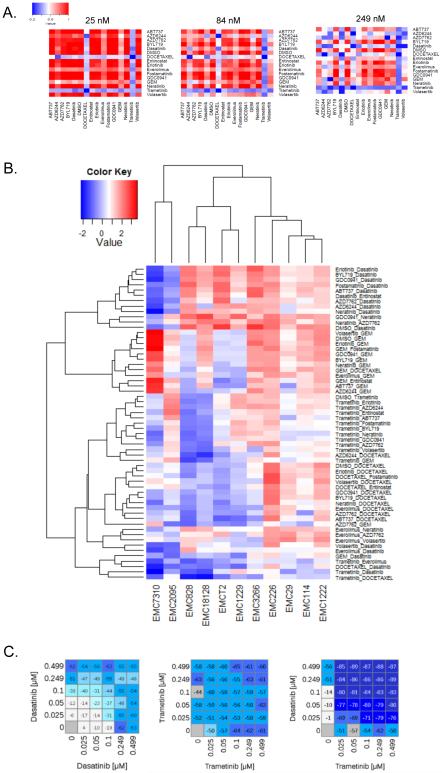

Combination therapies have the potential to increase the frequency and duration of therapeutic response. However, rational design of combination therapies remains difficult due to inadequate understanding of individual targets, drug interactions, and a paucity of biomarkers. Empirical approaches to uncovering combination therapy sensitivities have proved successful in defining new treatment strategies (Chen et al., 2012; Crystal et al., 2014; Vora et al., 2014). To test this approach in PDAC models, 14 clinically relevant drugs were evaluated in all pair-wise combinations across 11 different cell models at three doses yielding a total of 5880 sensitivity measures (Fig 4A, and Data Table 2). These analyses defined a unique pattern of sensitivity or “barcode” for each tumor model (Fig 4A and S4). In some cases, low dose responses to combination therapy increased an existing monotherapy sensitivity. For example EMC7310 was sensitive to dasatinib, but this sensitivity was augmented by multiple additional agents. However, there were many combinations that could not be predicted from single agent sensitivities, and surprisingly PI3K inhibitors (BYL719 and GDC0941) had little positive impact in combination with any other agent (Fig 4B and Data Table 2). To evaluate combinatorial potency, multi-drug dose response analyses were conducted and uncovered model-selective synergistic drug interactions (Fig 4C, S4 and Data Table 2). These data underscore the diversity of therapeutic response, and indicate that in spite of employing multiple combinations, there were no universal vulnerabilities in PDAC; however, subsets of cases were sensitive to select combination treatments.

Figure 4. Combination treatments.

(A) Representation of drug sensitivity to combination treatment. The sensitivity of all treatments was graphed and the color-bar indicates fractional survival relative to DMSO control. (B) Heat map clustering the AUC values of effective combinations in at least one of the cell lines. Cell lines and combinations were clustered based on Euclidean distance. (C) Representative dose response analysis of trametinib and dasatinib combination in a models that yielded synergistic toxicity. Value shown in the heatmap is percent survival minus 100 (i.e. 0 is no effect on survival, −100 is complete lack of survival).

The robust responses to select combinations did not associate with common genomic lesions (e.g. KRAS, TP53, SMAD4) present in models (not shown). Nor did they correspond to previously-described predictive markers. For example, the ratio of MCL1/NOXA implicated in resistance to ABT737, could not predict response to ABT737 in combination with chemotherapy (Geserick et al., 2014). Based on these results, gene expression features were explored relative to the response to select combination treatments. Analysis of top upregulated and downregulated genes revealed a relatively broad spectrum of deregulated biological processes. The elastic-net method was used to more stringently define genes that were positively or inversely correlated with the combinations tested. These combined approaches yielded few genes that were reproducibly associated with combinatorial sensitivities (Fig S4). Unfortunately, data from clinical studies employing the tested combinations are not available to validate the performance of the potential biomarkers and underscores the challenge associated with developing predictive markers for combination therapies.

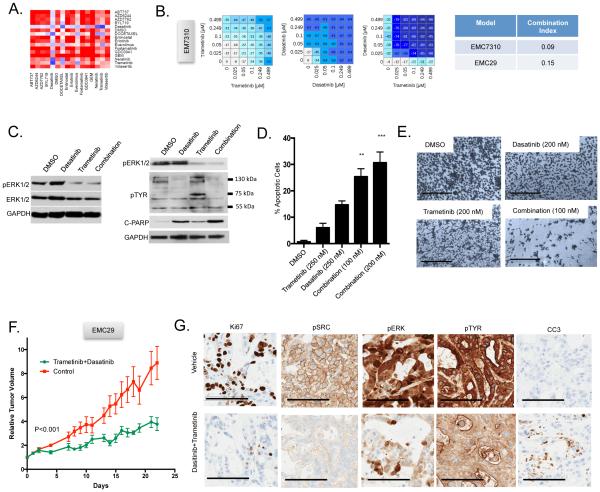

Tumor selective trametinib sensitivity translates to disease control in vivo

Amongst the agents tested, the MEK inhibitor trametinib exhibited potent combination activity with several agents (i.e. dasatinib, docetaxel and everolimus) and served as the backbone for a trial of cell line-encoded differential combinatorial sensitivities (Fig 5A). Trametinib in combination with dasatinib was effective in several models including EMC7310 and EMC29 (Fig 5B). In these models, trametinib alone induced compensatory tyrosine phosphorylation events that were blocked by dasatinib and associated with increased apoptosis (Fig 5C-E). These effects translated into control of tumorigenic growth in the corresponding PDX that, based on cell line data, would be predicted to be sensitive to this combination (Fig 5F). In contrast, another PDX model that would be predicted to be resistant to this combination failed to respond (Fig S5). Analysis of sensitive PDX tissues confirmed suppression of p-ERK1/2, p-Src, tyrosine phosphorylation, and the induction of apoptosis (Fig 5G).

Figure 5. Combinatorial sensitivity to dasatinib with trametinib.

(A) Combination treatment response bardcode from a cell line that is sensitive to dasatinib and trametinib combination. (B) Representative dose response analysis of trametinib and dasatinib combination in models that yielded synergistic toxicity. Value shown in the heatmap is percent survival minus 100 (i.e. 0 is no effect on survival, −100 is complete lack of survival) and the combination index for two cell lines is shown. (C) Representative immunoblot analysis of the indicated proteins in the sensitive model exposed to the indicated agents: trametinib 100 nM, dasatinib 100 nM, combination 50 nM of each agent. (D) Induction of cell death as a function of drug treatment from three independent cultures. The average and standard deviation are shown, statistical analysis was by t-test comparing the combination to single agent dasatinib treatment, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. (E) Representative 4x micrographs of cells on plates treated with the indicated drugs (scale bar is 1 mm). (F) The PDX was randomized to treatment with vehicle control (n=5) or the combination of trametinib and dasatinib (n=5). The average tumor volume and standard error of the mean are plotted. Mice were sacrificed when the control arm became moribund, statistical significance was determined by ANOVA. (G) Representative staining of the indicated markers by immunohistochemistry. The scale bar is 100 μm.

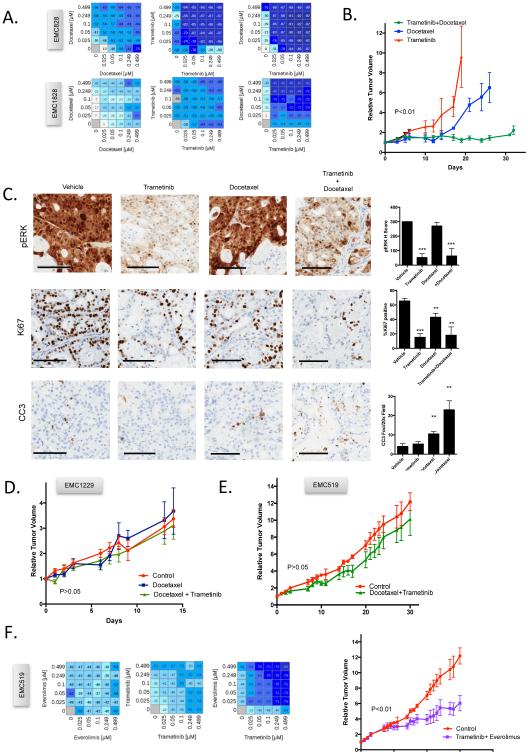

The combination of trametinib with docetaxel was the most potent treatment identified in cell lines screening, with synergistic interaction observed in several models (Fig 6A). In xenograft assays, this combination potently suppressed tumor growth for greater than 30 days in two PDX models (Fig 6B and S6). In contrast, single agent treatments with docetaxel or trametinib were insufficient to prevent rapid disease progression (Fig 6B and S6). Analysis of PDX tissue showed that MEK inhibition generally limited proliferation, docetaxel elicited cell death, while combination yielded dual response (Fig 6C). To determine if this therapeutic sensitivity was selective, the same treatment was deployed against two PDXs models that would be predicted, based on the cell line data, to be resistant. In these models there was veritably no response to the treatment (Fig 6D and E). These data indicate that therapeutic sensitivities identified in the primary cell lines translate into responses in PDX derived from the same primary tumor. To further interrogate the idea that sensitivities are model and combination specific, the EMC519 PDX (resistant to trametinib+docetaxel and trametinib+dasatinib combinations, but sensitive to trametinib-everolimus in cell line screens) was treated with trametinib and everolimus (Fig 6F). This combination yielded measurable control of the PDX tumor growth (Fig 6F). Together, these data suggest that cell models could be used to infer drug sensitivities to direct the combinatorial treatments.

Figure 6. Patient-selective targeting of trametinib combinations.

(A) Dose response analysis of combination treatment indicating synergistic interaction of trametinib and docetaxel in two models. Value shown in the heatmap is percent survival minus 100 (i.e. 0 is no effect on survival, −100 is complete lack of survival) (B) The PDX was randomized to treatment with single agent trametinib (n=4) or docetaxel (n=4) or the combination (n=5). Tumor volume was measured and the mean and standard error of the mean is shown. Mice were sacrificed when the single agent mice became moribund, or at the end of 33 days of treatment. (C) Representative immunohistochemistry and quantification. The average and standard deviation are shown from at least three tumors. Statistical analysis was by unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 relative to the vehicle control. The scale bar is 100 μm. (D/E) Two independent PDX models that were predicted to be resistant to trametinib+docetaxel failed to respond to treatment. p>0.05. (F) Dose response analysis of combination treatment indicating synergistic interaction of trametinib and everolimus from a model resistant to trametinib and docetaxel. Response of the PDX to trametinib and everolimus treatment (n=5 per arm). Tumor volume was measured and the mean and standard error of the mean is shown.

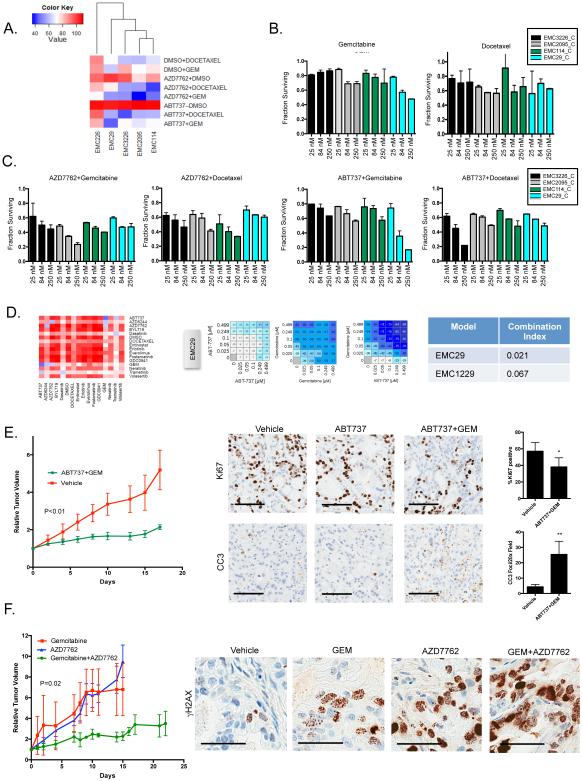

Model guided chemotherapy regimens

In the analysis of the combination drug screening data, it was apparent that select targeted agents cooperate with chemotherapy. As shown, the BCL2 inhibitor ABT737 and the checkpoint kinase inhibitor AZD7762 resulted in model specific augmentation of the response to either gemcitabine or docetaxel (Fig 7A-C). ABT737 was particularly potent when combined with gemcitabine or docetaxel in EMC29 and EMC3226 lines respectively (Fig 7 B and C). In contrast, AZD7762 impacted on a separate collection of cell lines. These data suggest underlying cellular vulnerabilities to apoptotic or cell cycle checkpoint inhibitors. The response to the combination of ABT737 and gemcitabine was synergistic in two cell models (Fig 7D), and in PDX translated to stable disease that was associated with modest effect of therapy on proliferation, but robust induction of apoptosis (Fig 7E). Similarly, the combination of AZD7762 with gemcitabine yielded disease control in the PDX model and the response was accompanied by extensive DNA damage (Fig 7F). Together, these data similarly illustrate that combinations with chemotherapy can be effective, but must be directed.

Figure 7. Differential cooperation of apoptotic and cell cycle checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy.

(A) Heatmap showing the AUC of single and combination treatments with ABT737 or AZD7762 and chemotherapy. Cell lines and drugs were clustered based on Euclidian distance. (B) Relative survival of the indicated cell lines treated with increasing concentrations (25, 84, 250 nM) of gemcitabine or docetaxel as measured in triplicate from two independent experiments (C) Relative survival of the indicated cell lines treated with increasing concentrations (25, 84, 250 nM) of the indicated drug combinations as measured in triplicate from two independent experiments (D) Summary of the cooperation between ABT737 and gemcitabine in a sensitive model. Dose response analysis of combination treatments indicating selective synergistic interaction in the EMC29 model and related cooperative index. Value shown in the heatmap is percent survival minus 100 (ie. 0 is no effect on survival, −100 is complete lack of survival) (E) The PDX was randomized to treatment with vehicle control (n=3) or gemcitabine and ABT737 (n=8) and tumor volume was determined. The average tumor volume and standard error of the mean are plotted. Mice were sacrificed when the control arm became moribund. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA. Representative staining and quantitation of the indicated markers by immunohistochemistry. The average and standard deviation are shown. The scale bar is 100 μm. Statistical analysis was by unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (F) A PDX model sensitive to AZD7762 and gemcitabine was treated singly or in combination (n=5 per arm). Tumor volume was measured as a function of time and statistical significance was determined by ANOVA. Representative γH2AX staining is shown (scale bar is 50 μm).

Discussion

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma has a particularly poor prognosis, and even with new targeted therapies and chemotherapy, the survival is poor. Here we show that patient-derived models can be developed and used to investigate therapeutic sensitivities determined by genetic features of the disease and to identify empirical therapeutic vulnerabilities. These data reveal several key points that are of prime relevance to pancreatic cancer and tumor biology in general.

The challenges of employing genetic analysis to inform treatment in PDAC

Precision oncology is dependent on the existence of known vulnerabilities encoded by high-potency genetic events, and drugs capable of exploiting these vulnerabilities. At present, the repertoire of actionable genetic events in PDAC is limited. Rare BRAF V600E mutations are identified in PDAC and could represent the basis for targeted inhibition as our group and others have previously published (Collisson et al., 2012; Witkiewicz et al., 2015). Similarly, germline BRCA-deficiency is the basis for ongoing PARP inhibitor clinical trials (Lowery et al., 2011). As shown here, out of 28 cases only one genetic event was identified that yielded sensitivity to a therapeutic strategy. In this case, existence of the matched model allowed us to confirm the biological relevance of the STAG2 mutation by showing sensitivity of the model to DNA cross-linking agent. Therefore, annotated patient-derived models provide a substrate upon which to functionally dissect the significance of novel and potentially actionable genetic events that occur within a tumor.

Another challenge of genomics-driven personalized medicine is assessing the effect of specific molecular aberrations on therapeutic response in the context of complex genetic changes present in individual tumors. For example, KRAS has been proposed to modify therapeutic dependency to EZH2 inhibitors (Kim et al., 2015), and in the models tested responses to this class of drugs were not uniformly present in cases harboring mutations in chromatin remodeling genes. This finding suggests that although tumors acquire genetic alterations in specific genes, the implicated pathway may not be functionally inactive or therapeutically actionable. Therefore, annotated patient-derived models provide a unique test-bed for interrogating specific therapeutic dependencies in a genetically tractable system.

Empirical definition of therapeutic sensitivities and clinical relevance

Cell lines offer the advantage of the ability to conduct high-throughput approaches to interrogate many therapeutic agents. A large number of failed clinical trials have demonstrated the difficulty in treating PDAC. Based on the data herein, the paucity of clinical success is most probably due to the diverse therapeutic sensitivity of individual PDAC cases, suggesting that with an unselected patient population it will be veritably impossible to demonstrate clinical benefit. Additionally, very few models exhibited an exceptional response to single agents across the breadth of a library encompassing 305 agents. We could identify only one tumor that was particularly sensitive to MEK inhibition and another model that was sensitive to EGFR and Tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

In contrast to the limited activity of single agents, combination screens yielded responses at low-dose concentrations in the majority of models. Specific combinations were effective across several models, indicating that by potentially screening more models therapeutic sensitivity clades of PDAC will emerge. In the pharmacological screens performed in this study, MEK inhibition coupled with MTOR, docetaxel, or Tyrosine kinase inhibitors was effective in ~30% of models tested. Resistance to MEK inhibitors occurs through several mechanisms including upregulation of oncogenic bypass signaling pathways such as AKT, Tyrosine kinase or MTOR signaling. In the clinic, the MEK and MTOR inhibitors (e.g. NCT02583542) are being tested. An intriguing finding from the drug screen was sensitivity of a subset of models to combined MEK and docetaxel inhibition. This combination has been observed to synergistically enhance apoptosis and inhibit tumor growth in human xenograft tumor models (Balko et al., 2012; McDaid et al., 2005) and is currently being tested in a phase III study in patients with KRAS mutated advanced non small-cell lung adenocarcinoma (Janne et al., 2016). Interestingly, in the models tested herein, there was limited sensitivity imparted through the combination of gemcitabine and MEK inhibition. This potentially explains why combination of MEK inhibitor and gemcitabine tested in the clinic did not show improved efficacy over gemcitabine (Infante et al., 2014). Another promising strategy that emerged from this study involves using CHK or BCL2 inhibitors as agents that drive enhanced sensitivity to chemotherapy. Together, the data suggest that majority of PDAC tumors have intrinsic therapeutic sensitivities, but the challenge is to prospectively identify effective treatment.

Patient derived models based approach to precision medicine

This study supports a path for guiding patient treatment based on the integration of genetic and empirically determined sensitivities of the patient’s tumor (Fig S7). In reference to defined genetic susceptibilities, the models provide a means to interrogate the voracity of specific drug targets. Parallel unbiased screening enables discovery of sensitivities that could be exploited in the clinic. The model-guided treatment must be optimized, allowing for the generation of data in a timeframe compatible with clinical decision-making and appropriately validated. In the current study, the majority of models were developed, cell lines drug screened, and select hits validated in PDX models within a 10-12 month window (Fig S7). This chronology would allow time to inform front line therapy for recurrent disease for most patients who were surgically resected and treated with standard of care, where the median time to recurrence is approximately 14 months (Saif, 2013). Although most models were generated from surgically resected specimens, two of the models (EMC3226 and EMC62) were established from primary tumor biopsies indicating that this approach could be used with only limited amount of tumor tissue available. In the context of inoperable pancreatic cancer, application of data from a cell line screen without in vivo validation in PDX, would permit generation of sensitivity data in the timeframe compatible with treatment. We acknowledge that model–guided treatment is also not without significant logistical hurdles, including the availability of drugs for patient treatment, clinically relevant timeframes, patient-performance status, toxicity of combination regiments, and quality metrics related to model development and therapeutic response evaluation. Additionally, it will be very important to monitor ex vivo genetic and phenotypic divergence with passage and try to understand features of tumor heterogeneity that could undermine the efficacy of using models to direct treatment. As shown here drug sensitivities remained stable with passage in cell culture, and importantly, were confirmed in PDX models suggesting that the dominant genetic drivers and related therapeutic sensitivities are conserved.

In spite of these challenges, progressively more effort is going into the development of patient-derived models for guidance of disease treatment (Aparicio et al., 2015; Boj et al., 2015; Crystal et al., 2014; van de Wetering et al., 2015). Several ongoing trials employ PDX models to direct a limited repertoire of agents (e.g. NCT02312245, NCT02720796, ERCAVATAR2015). Given the experience here, PDAC cell lines would provide the opportunity to rapidly interrogate a larger portfolio of combinations that could be used to guide patient care and provide a novel approach to precision medicine. Validation of this approach would require the establishment of challenging multi-arm or N-of-1 clinical trials. However, considering the dire outcome for PDAC patients and long lasting difficulty in developing effective treatments, this non-canonical approach might be particularly impactful in pancreatic cancer.

Methods

Cell Culture

Primary cell models were established and cultured on collagen coated tissue culture plates in supplemented KSF media. Cells were passaged by trypsinization and employed at early (p<5) and late passage (p>20) for the analysis of drug sensitivity. Established cell lines were from ATCC and cultured using published methodology. The detailed description of these models will be published elsewhere, but the description of the derivation approach is provided in the Extended Methods.

Drug treatments

Cell models were subjected to drug screening with libraries, combination treatments, and single agents as summarized in the Extended Methods section. The treatment of PDX models was in accordance with IACUC protocols and is summarized in the Extended Methods.

Immunohistochemistry and model analysis

Immunohistochemistry was performed on a DAKO stainer using conditions as described in the Extended Methods. Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, RPPA analysis, flow cytometry, and other methods employed standard procedures. The specific features of the experimentation are provided in the Extended Methods. RNA sequencing was performed on an Illumina instrument with paired-end reads and the expression values are deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession number GSE79982.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank members of the Knudsen and Witkiewicz laboratory for thought-provoking discussion, technical assistance, and help with manuscript preparation. Nicholas Borja and Eboni Holloman assisted with select animal studies. Ngoc Haoi assisted with informatics and figure development. The Tissue Management Shared Resource of the Simmons Cancer Center (Cheryl Lewis, Manager) assisted with the acquisition of the tissue and coordinating histological and immunohistochemical analysis of tumor specimens. The High Throughput Screening core and Tissue Management Shared Resource are supported by the Cancer Center Support Grant of the Simmons Cancer Center (P30 CA142543). The research is supported by grants to ESK and AKW from the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AKW, ESK

Methodology: ESK, AKW, CE, BP

Software: UB, EM

Formal Analysis: UB, CE, BP

Investigation: AKW, UB, CE, EM, BP, GBM, ESK

Resources: AKW, BP, GBM, EMO, ESK

Data Curation: UB

Writing: ESK, AKW, EMO

Visualization: UB, CE, ESK, AKW

Supervision: ESK, BP, AKW

Funding Acquisition: ESK, AKW

Jointly directed the research and are fully responsible for this manuscript: AKW, ESK

References

- Almhanna K, Philip PA. Defining new paradigms for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2011;12:111–125. doi: 10.1007/s11864-011-0150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio S, Hidalgo M, Kung AL. Examining the utility of patient-derived xenograft mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nrc3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson SJ, Rehm HL. Building the foundation for genomics in precision medicine. Nature. 2015;526:336–342. doi: 10.1038/nature15816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch AM, Gingras MC, Miller DK, Christ AN, Bruxner TJ, Quinn MC, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balko JM, Cook RS, Vaught DB, Kuba MG, Miller TW, Bhola NE, Sanders ME, Granja-Ingram NM, Smith JJ, Meszoely IM, et al. Profiling of residual breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy identifies DUSP4 deficiency as a mechanism of drug resistance. Nature medicine. 2012;18:1052–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm.2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biankin AV, Piantadosi S, Hollingsworth SJ. Patient-centric trials for therapeutic development in precision oncology. Nature. 2015;526:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nature15819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitler BG, Aird KM, Garipov A, Li H, Amatangelo M, Kossenkov AV, Schultz DC, Liu Q, Shih Ie M, Conejo-Garcia JR, et al. Synthetic lethality by targeting EZH2 methyltransferase activity in ARID1A-mutated cancers. Nature medicine. 2015;21:231–238. doi: 10.1038/nm.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boj SF, Hwang CI, Baker LA, Chio II, Engle DD, Corbo V, Jager M, Ponz-Sarvise M, Tiriac H, Spector MS, et al. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2015;160:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Cheng K, Walton Z, Wang Y, Ebi H, Shimamura T, Liu Y, Tupper T, Ouyang J, Li J, et al. A murine lung cancer co-clinical trial identifies genetic modifiers of therapeutic response. Nature. 2012;483:613–617. doi: 10.1038/nature10937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, Gibb WJ, Truitt M, Gu S, Cooc J, Weinkle J, Kim GE, Jakkula L, et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their tdiffering responses to therapy. Nature medicine. 2011;17:500–503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collisson EA, Trejo CL, Silva JM, Gu S, Korkola JE, Heiser LM, Charles RP, Rabinovich BA, Hann B, Dankort D, et al. A central role for RAF-->MEK-->ERK signaling in the genesis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:685–693. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal AS, Shaw AT, Sequist LV, Friboulet L, Niederst MJ, Lockerman EL, Frias RL, Gainor JF, Amzallag A, Greninger P, et al. Patient-derived models of acquired resistance can identify effective drug combinations for cancer. Science. 2014;346:1480–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.1254721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluche E, Onesti E, Andre F. Precision medicine for metastatic breast cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015:e2–7. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers L, Perez-Mancera PA, Lenkiewicz E, Tang N, Aust D, Knosel T, Rummele P, Holley T, Kassner M, Aziz M, et al. STAG2 is a clinically relevant tumor suppressor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genome medicine. 2014;6:9. doi: 10.1186/gm526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Laguna I, Tometich D, Hu N, Ying J, Geiersbach K, Whisenant J, Wang K, Ross JS, Sharma S. N of 1 case reports of exceptional responders accrued from pancreatic cancer patients enrolled in first-in-man studies from 2002 through 2012. Oncoscience. 2015;2:285–293. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geserick P, Wang J, Feoktistova M, Leverkus M. The ratio of Mcl-1 and Noxa determines ABT737 resistance in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cell death & disease 5, e1412. 2014 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante JR, Somer BG, Park JO, Li CP, Scheulen ME, Kasubhai SM, Oh DY, Liu Y, Redhu S, Steplewski K, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of trametinib, an oral MEK inhibitor, in combination with gemcitabine for patients with untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:2072–2081. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janne PA, Mann H, Ghiorghiu D. Study Design and Rationale for a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Selumetinib in Combination With Docetaxel as Second-Line Treatment in Patients With KRAS-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (SELECT-1) Clinical lung cancer. 2016;17:e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Kamiyama H, Jimeno A, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Kim W, Howard TP, Vazquez F, Tsherniak A, Wu JN, Wang W, Haswell JR, Walensky LD, Hahn WC, et al. SWI/SNF-mutant cancers depend on catalytic and non-catalytic activity of EZH2. Nature medicine. 2015;21:1491–1496. doi: 10.1038/nm.3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleger A, Perkhofer L, Seufferlein T. Smarter drugs emerging in pancreatic cancer therapy. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2014 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, Chitale DA, Dacic S, Giaccone G, Jenkins RB, Kwiatkowski DJ, Saldivar JS, Squire J, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:415–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery MA, Kelsen DP, Stadler ZK, Yu KH, Janjigian YY, Ludwig E, D'Adamo DR, Salo-Mullen E, Robson ME, Allen PJ, et al. An emerging entity: pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with a known BRCA mutation: clinical descriptors, treatment implications, and future directions. Oncologist. 2011;16:1397–1402. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaid HM, Lopez-Barcons L, Grossman A, Lia M, Keller S, Perez-Soler R, Horwitz SB. Enhancement of the therapeutic efficacy of taxol by the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor CI-1040 in nude mice bearing human heterotransplants. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2854–2860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzoeva OK, Das D, Heiser LM, Bhattacharya S, Siwak D, Gendelman R, Bayani N, Wang NJ, Neve RM, Guan Y, et al. Basal subtype and MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK)-phosphoinositide 3-kinase feedback signaling determine susceptibility of breast cancer cells to MEK inhibition. Cancer Res. 2009;69:565–572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson AS, Tran Cao HS, Tempero MA, Lowy AM. Therapeutic advances in pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1316–1326. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettazzoni P, Viale A, Shah P, Carugo A, Ying H, Wang H, Genovese G, Seth S, Minelli R, Green T, et al. Genetic events that limit the efficacy of MEK and RTK inhibitor therapies in a mouse model of KRAS-driven pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1091–1101. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saif MW. Advancements in the management of pancreatic cancer: 2013. JOP : Journal of the pancreas. 2013;14:112–118. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D, Koopman L, Violette S, Bardeesy N, Settleman J. A gene expression signature associated with "K-Ras addiction" reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DA, Kim T, Diaz-Martinez LA, Fair J, Elkahloun AG, Harris BT, Toretsky JA, Rosenberg SA, Shukla N, Ladanyi M, et al. Mutational inactivation of STAG2 causes aneuploidy in human cancer. Science. 2011;333:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1203619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M, Francies HE, Francis JM, Bounova G, Iorio F, Pronk A, van Houdt W, van Gorp J, Taylor-Weiner A, Kester L, et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell. 2015;161:933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora SR, Juric D, Kim N, Mino-Kenudson M, Huynh T, Costa C, Lockerman EL, Pollack SF, Liu M, Li X, et al. CDK 4/6 Inhibitors Sensitize PIK3CA Mutant Breast Cancer to PI3K Inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch AM, Chang DK, Kassahn KS, Bailey P, Johns AL, Miller D, Nones K, Quek K, et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewicz AK, McMillan EA, Balaji U, Baek G, Lin WC, Mansour J, Mollaee M, Wagner KU, Koduru P, Yopp A, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nature communications 6, 6744. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sitzmann JV, Hruban RH, Goodman SN, Dooley WC, Coleman J, Pitt HA. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;221:721–731. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00011. discussion 731-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.