Abstract

Estrogen receptor-α (ERα) mediates the essential biological function of estrogen in breast development and tumorigenesis. Multiple mechanisms, including pioneer factors, coregulators, and epigenetic modifications have been identified as regulators of ERα signaling in breast cancer. However, previous studies of ERα regulation have focused on luminal and HER2-positive subtypes rather than basal-like breast cancer (BLBC), in which ERα is underexpressed. In addition, mechanisms that account for the decrease or loss of ER expression in recurrent tumors after endocrine therapy remain elusive. Here, we demonstrate a novel FOXC1-driven mechanism that suppresses ERα expression in breast cancer. We find that FOXC1 competes with GATA3 for the same binding regions in the cis-regulatory elements (CREs) upstream of the ERα gene and thereby downregulates ERα expression and consequently its transcriptional activity. The forkhead domain of FOXC1 is essential for the competition with GATA3 for DNA binding. Counteracting the action of GATA3 at the ERα promoter region, overexpression of FOXC1 hinders recruitment of RNA polymerase II and increases histone H3K9 trimethylation at ERα promoters. Importantly, ectopic FOXC1 expression in luminal breast cancer cells reduces sensitivity to estrogen and tamoxifen. Furthermore, in breast cancer patients with ER-positive primary tumors who received adjuvant tamoxifen treatment, FOXC1 expression is associated with decreased or undetectable ER expression in recurrent tumors. Our findings highlight a clinically relevant mechanism that contributes to the low or absent ERα expression in BLBC. This study suggests a new paradigm to study ERα regulation during breast cancer progression and indicates a role of FOXC1 in the modulation of cellular response to endocrine treatment.

Keywords: breast cancer, endocrine therapy, ERα, FOXC1, GATA3

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer can be classified into four major molecular subtypes including luminal A, luminal B, HER2-positive, and basal-like breast cancer (BLBC) based on different gene expression signatures.1 The luminal subtype is characterized by estrogen receptor expression (ER-positive), whereas BLBC often has a triple-negative phenotype (ER-negative/PR-negative/HER2-negative).2 Notably, the molecular subtypes display highly significant differences in the choices of treatment strategies and prediction of recurrence, metastasis, and survival.3 Luminal breast cancer is usually associated with a less aggressive cancer phenotype and more favorable prognostic outcome compared to patients with BLBC.3 Estrogen signaling is a target for endocrine therapy, and greater ERα expression correlates with a better response to endocrine therapy, including tamoxifen.4 In contrast, the only option at present for systemic therapy of BLBC is chemotherapy due to the lack of targetable markers.5

A number of studies have addressed the regulatory mechanisms of estrogen signaling in breast cancer. Pioneer factor FOXA16, GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3),7 coactivators and corepressors,8 epigenetic modifications such as promoter hypermethylation,9 and ERα ubiquitination10 have been identified as regulators of ERα expression and transcriptional activity. While previous work has greatly advanced our understanding of the function and regulation of ERα in luminal breast cancer, less is known about the mechanisms restricting ERα expression in BLBC. Additionally, up to ~30% of ER-positive breast tumors have been reported to recur with an ER-negative phenotype after endocrine therapy.11 It is not clear what causes the diminished ERα expression and endocrine therapy resistance.11 Unraveling the mechanism inhibiting ERα will provide a new insight into the molecular basis of ERα-negative breast cancer and a possible explanation for ERα status changes during antiestrogen treatment.

FOXC1, a member of the forkhead box (FOX) transcription factor superfamily, plays important roles in the development of the brain, heart, and eye during the embryogenesis.12 A recent study demonstrated FOXC1 as a pivotal diagnostic marker for BLBC.13, 14 In addition to BLBC, FOXC1 is associated with other types of cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma,15 gastric cancer,16 and non-small cell lung cancer.17 FOXC1 stimulates human cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion.14 As opposed to ERα, the expression of FOXC1 is low or absent in luminal breast cancer cells.14 The fact that FOXC1 and ERα are highly associated with two different breast cancer subtypes and their expressions are mutually exclusive has prompted us to postulate negative regulation between the two transcription factors. In this study, we characterize the effect of FOXC1 on ERα expression in breast cancer cells and explore the possible mechanism of this inhibition. It offers new mechanistic insight into FOXC1-relavant endocrine resistance and ER-positive breast cancer recurrence.

RESULTS

FOXC1 downregulates ERα expression and its transcriptional activity

We first confirmed the inverse correlation of ERα and FOXC1 in breast cancer tissues using expression data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provisional datasets at cBioPortal (www.cbioportal.org) (Supplementary Figure S1a) and breast cancer cell lines (Supplementary Figure S1b and S1c). Then we sought to determine if FOXC1 regulates ERα expression. Quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (qRT-PCR) results suggested that overexpression of FOXC1 in three common luminal breast cancer cell lines led to reduced mRNA expression of ERα (ESR1), but not ERβ (ESR2) (Figure 1a). In agreement with these results, protein levels of ERα and progesterone receptor (PR), a well-established estrogen-regulated gene,18 were decreased by FOXC1 overexpression in those luminal breast cancer cell lines (Figure 1b and Supplementary Figure S1d).

Figure 1. FOXC1 inhibits ERα expression and transcriptional activity.

Luminal breast cancer cell lines MCF-7, T47D, and ZR75 were transfected with vector or FOXC1. (a) mRNA levels of ERα (ESR1) (left) and ERβ (ESR2) (right) were measured by qRT-PCR. (b) Protein levels of ERα and PR were analyzed by immunoblotting. Actin was used as a loading control. (c) MCF-7 and T47D cells were transiently cotransfected with ERE-luc, vector, or FOXC1 construct. Luciferase signals were detected. (d) MCF-7 cells were transfected with vector or FOXC1, and ChIP assays using anti-ERα antibodies followed by qPCR were performed to measure the binding between ERα and ERE. (e) mRNA expression of RARα, PR, GREB-1, XBP-1, TFF-1, and NRIP-1 were analyzed by qRT-PCR in MCF-7 cells with FOXC1 overexpression. (f) The protein expression of ERα regulators was assessed in FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 cells. ****, P<0.0001; ***, P<0.001; **, P<0.01; *, P<0.05.

We then assessed the effect of FOXC1 overexpression on ERα transcriptional activity. According to the result of estrogen response element (ERE)-luciferase reporter assays, reduced ERE-luciferase signals were detected in the FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 and T47D cells relative to vector control (Figure 1c). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays followed by qPCR analysis were further performed to determine if the reduced luciferase signaling is due to the decreased binding between ERα and EREs. Three well-known ERα-regulated genes including growth regulation by estrogen in breast cancer 1 (GREB-1),19 X-Box Binding Protein 1 (XBP-1),20 and retinoic acid receptor α (RARα)21 were selected for this purpose. A Previous study has identified the ERE in the promoters of the three genes.22 As indicated in Figure 1d, FOXC1 overexpression has reduced ERα expression, giving rise to decreased ERα binding to the responsive DNA elements of GREB-1, XBP-1, and RARα in MCF-7 cells. To corroborate these findings, we investigated the mRNA levels of several additional ERα-targeted genes including trefoil Factor 1 (TFF-1)23 and nuclear receptor interacting protein 1(NRIP-1)24 in MCF-7 cells. As expected, mRNA levels of these molecules were significantly lower in FOXC1-overexpressing cells relative to vector except for TFF-1 (Figure 1e). Although TFF-1 is a well-known model gene for ERα activity, our recently published study has demonstrated that TFF-1 mRNA level was not affected by FOXC1 overexpression in T47D cells (GEO: GSE73234).25 FOXC1 may regulate TFF-1 by some additional unknown mechanisms and therefore the overall change of TFF-1 level is not significant. Collectively, our data suggest that FOXC1 downregulates ERα expression and thereby decreases its transcriptional activity.

Last, we determined if FOXC1 suppresses ERα expression by inhibiting the expression of ERα regulators. Immunoblotting showed that levels of GATA37 and FOXM126 were mildly decreased in FOXC1-overexpressing cells. In contrast, levels of FOXO3A,27 FOXA1,6 pre-B-cell leukemia homeobox 1 (PBX-1),28 estrogen receptor coactivator (AIB1),29 and SP130 remained unchanged (Figure 1f and Supplementary Figure S1e). Therefore, the results suggest a direct effect of FOXC1 on GATA3/FOXM1 as a potential mechanism responsible for ERα downregulation. However, contrary to the remarkably lowered ERα expression induced by FOXC1 presented in Figure 1b, the expression of GATA3 only slightly decreased (Figure 1f). Hence we reasoned that there is an alternative inhibitory mechanism dominating ERα silencing.

FOXC1 prevents GATA3 binding to the same regulatory regions upstream of the ERα gene

FOXC1 is known to bind to a nine-base-pair core sequence 5′-GTAAA(T/C)A(A/T/C)(A/T/G)-3′.31 Based on the consensus sequence, we found three putative FOXC1 binding sites located at enhancer 1 and promoters B and C upstream of the ERα gene (Figure 2a). The genomic organization of human ERα gene regulatory region was illustrated based on previous studies.7, 32 FOXC1 in vivo binding to the three sites was validated by ChIP-qPCR analysis of the immunoprecipitated DNA in MCF-7 cells. As expected, overexpression of FOXC1 considerably enhanced the recruitment of FOXC1 to all three sites in the regulatory regions of ERα compared to control (Figure 2b, left). We then speculated that these direct FOXC1-DNA interactions interfere with the accessibility of transcription factors or coregulators that consequently leads to the inhibition of ERα expression. GATA3, a well-studied transcription factor with a DNA consensus binding sequence 5′-(A/T)GATA(A/G)-3′, positively regulates expression of ERα.7 We have also verified that GATA3 is a positive regulator of ERα mRNA and protein expression in the MCF-7 cells used in this study (Supplementary Figure S2a). In reference to the previous reports7, 33 and the consensus DNA-binding sequences of the well-known ERα regulators, we identified GATA3 binding sites in proximity to or overlapping with the three above experimentally confirmed FOXC1 sites (Figure 2a). Prior to examining the possible binding competition between GATA3 and FOXC1, we systematically assessed GATA3 expression in relation to FOXC1. FOXC1 overexpression decreased the GATA3 mRNA and protein expression in MCF-7 cells, while FOXC1 overexpression exerted no effect on GATA3 expression in T47D and ZR-75 cells (Supplementary Figure S2b). The mRNA expression levels of GATA3 and FOXC1 are inversely correlated according to the TCGA provisional dataset (Supplementary Figure S2c). However, as presented in Supplementary Figure S2d, albeit at low level, both GATA3 mRNA and protein expression were still detectable in BLBC cell lines including BT549, HCC1806, and MDA-MB-468. Notably, a previous study showed that GATA3 labeling was seen in 43–67% of triple-negative breast cancer cases, with the intensity of GATA3 staining weaker in triple-negative relative to luminal breast cancers.34

Figure 2. FOXC1 and GATA3 interact with CREs upstream of the ERα gene.

(a) A schematic picture described the ERα genomic sequence containing the FOXC1 and GATA3 binding sites. The transcription start site was indicated as +1. Colored blocks, localization of regions targeted by qRT-PCR primers used to analyze ChIP assays. GATA3 (bold red) and FOXC1 (bold blue) and overlapped (bold purple) consensus sequences in enhancer 1, promoters B and C were marked. All FOXC1 binding sites and GATA3 binding site at promoter B were predicted by JASPAR program. GATA3 binding sites at enhancer 1, 2, and promoter C were as published.7, 33 (b) MCF-7 cells were stably transfected with FOXC1 or vector, the binding of FOXC1 and GATA3 to the enhancer 1, promoters B and C were measured by ChIP assays. Normal IgG was used as a negative control. The ratio of binding signal to input was compared. (c) The sequences of the biotinylated oligonucleotide probes at ERα enhancer and promoter C are underlined. (d) Total nuclear protein from vector or FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 cells were extracted and incubated with the biotin-labeled probes. The protein bound DNA probes were precipitated and detected with anti-FOXC1 or anti-GATA3 antibodies. ***, P<0.001; **, P<0.01; *, P<0.05.

We then investigated if FOXC1 repels GATA3 from binding to the same regions in the CREs of the ERα gene. As demonstrated in Figure 2b (right), FOXC1 overexpression greatly reduced the binding of GATA3 to the previously characterized sites at both the enhancer 1 and promoter C, but not to the predicted sites at promoter B, when compared with vector. This result is likely attributed to the fact that GATA3 does not bind to the predicted site at promoter B. To address this question, we performed ChIP assays to show that the binding capacity of GATA3 to promoter B, which was remarkably low relative to GATA3 binding to the enhancer 1, was not affected by GATA3 siRNA-mediated knockdown (Supplementary Figure S3a).

We further identified the critical nucleotides upstream of the ERα gene recognized by FOXC1 and GATA3. Each region at the enhancer 1 and promoter C contains two clusters of GATA3 binding sites (probes 1 and 2 for enhancer 1, probes 3 and 4 for promoter C) and only one of each two clusters has an overlapping FOXC1 site (probe 2 for enhancer 1 and probe 4 for promoter C) (Figure 2c). As indicated in the result of the biotinylated oligonucleotide precipitation assay, probes 1 and 3 were unable to capture FOXC1 protein in FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 cell lysates due to the lack of a binding site (Figure 2d). The binding of GATA3 to probe 1 was slightly weakened by FOXC1 overexpression, likely due to the reduced GATA3 expression. Notably, the binding of GATA3 to probe 3 was not affected. In contrast, a strong signal of FOXC1 pull-down by probes 2 and 4 was detected in FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 cells, indicating the interaction between FOXC1 and probes 2 and 4 in vitro. FOXC1 overexpression caused the diminished binding of GATA3 to probes 2 and 4 relative to vector control (Figure 2d, Supplementary Figure S3b and S3c). This is due to the occupation of the shared FOXC1/GATA3 binding sites by FOXC1 protein.

Last, we aimed to confirm that direct inhibition of FOXC1 on GATA3 is only a minor mechanism in ERα silencing. For this purpose, we did a ChIP assay to compare GATA3 and FOXC1 binding to enhancer 2 of ERα in MCF-7 cells (Figure 2a). Enhancer 2 has no putative FOXC1 binding site. The ChIP-qPCR results confirmed that binding between FOXC1 and enhancer 2 was no different than the binding between IgG negative control and enhancer 2 in FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 cells (Supplementary Figure S3d, left). On the other hand, GATA3 is reported to directly interact with enhancer 2.7 We demonstrated that the interaction between GATA3 and enhancer 2 was only slightly inhibited by FOXC1 overexpression (Supplementary Figure S3d, right). This slight reduction is likely caused by the inhibition of GATA3 expression by FOXC1. However, due to the lack of competition from FOXC1 for the similar binding site at enhancer 2, the majority of GATA3 and enhancer 2 interactions were still maintained. This result supports our hypothesis that effect of FOXC1 counteracting GATA3 mostly relies on the competition for the similar binding sites in the regulatory regions of the ERα gene.

FOXC1 hinders the recruitment of RNA polymerase II (RNA polII) and enhances the trimethylation of histone H3 Lysine 9 (H3K9 me3) at ERα promoters in luminal and BLBC cells

GATA3 is required for RNA polII recruitment to the ERα gene.7 Specifically, RNA polII binding at promoters A and D (Figure 2a) can be inhibited by GATA3 silencing.7 It is suggested that the binding of GATA3 to the enhancer regions likely regulates ERα promoters through long-range enhancer-promoter interactions.35, 36 Given the findings that FOXC1 repels GATA3 from binding to the regulatory regions of ERα, we postulated that FOXC1 overexpression interferes with RNA polII recruitment and therefore inhibits the transcription of ERα. ChIP assays showed that FOXC1 overexpression was associated with drastically decreased RNA polII binding at promoter A (Figure 3a). Thus our data suggest that FOXC1 inhibits GATA3-mediated RNA polII recruitment to the promoter of ERα.

Figure 3. Recruitment of RNA polII, H3K9me3, and KDM4B to the ERα gene.

MCF-7 cells were transfected with FOXC1 or vector and ChIP assays were performed. (a) Recruitment of (a) RNA polII, (b) H3K9me3, and (c) KDM4B to different regulatory regions of ERα was measured by qPCR. BT549 cells with vector or FOXC1 knockout were subjected to ChIP-qPCR analysis. Bindings of (d) FOXC1 and GATA3, (e) RNA polII, and (f) H3K9me3 were compared. ****, P<0.0001; ***, P<0.001; **, P<0.01; *, P<0.05.

Notably, GATA3 forms a complex with and is required for KDM4B, the histone H3 lysine 9 tri-/dimethyl demethylase, to positively regulate ERα gene expression in luminal breast cancer cells.37 KDM4B depletion increases H3K9me3 marks and decreases GATA3 binding to the ER gene.37 Therefore we were interested to know if the blockage of GATA3 binding by FOXC1 induces any changes in H3K9me3 marks across ERα promoter regions. We confirmed that in FOXC1-overexpressing cells, H3K9me3 was highly enriched at promoters A and D (Figure 3b), the two regions which were previously shown to be enriched with histone modification.7 This result suggests that FOXC1 suppresses ERα expression via the induction of H3K9me3 enrichment at ERα promoters. In fact, the increase in H3K9me3 marks could be the consequence of an increased enrichment of the nucleosome population. We excluded this possibility by showing via immunoblotting that FOXC1 overexpression did not induce any changes on H3 protein level in MCF-7 cells (Supplementary Figure S4a). Moreover, as expected, FOXC1 overexpression impaired the binding of KDM4B to enhancer 1 and promoter C (Figure 3c).

To decipher the mechanism of FOXC1-induced ERα inhibition in a more physiologically relevant model, we examined the recruitment of FOXC1 and GATA3 to the ERα gene in BLBC cell lines. As presented in Figure 3d, FOXC1 knockout in BT549 cells significantly reduced the interaction of FOXC1 and enhancer 1 of the ERα gene, and this in turn led to the enhanced binding of GATA3 to the similar binding site at enhancer 1. The weakened interaction between FOXC1 and enhancer 1 is associated with enrichment of RNA polII at promoter A (Figure 3e) and decreased tri-methylation of H3K9 at promoter A and D (Figure 3f). These results suggest that FOXC1-driven ERα silencing is applicable to BLBC cells.

To provide additional evidence for FOXC1 inhibiting ERα, we performed immunoblotting analysis to measure ERα protein expression when the effect of FOXC1 is removed. We showed that FOXC1 knockout moderately elevated GATA3 protein expression in BT549 cell lines but has no effects on GATA3 expression in SUM149 cells (Supplementary Figure S4b). However, FOXC1 depletion could not restore ERα expression in either cell line (Supplementary Figure S4b). Given that ER promoters are highly hypermethylated in BLBC cell lines such as BT549,38 we treated the cells with 5-AZA, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor. As expected, we detected an increase in ERα mRNA when DNA methylation was inhibited by 5-AZA in BT549 and SUM 149 cells, and the increase was more dramatic when FOXC1 was depleted (Supplementary Figure S4c). Intriguingly, we were still unable to detect any ERα protein in response to 5-AZA treatment in both vector and FOXC1-depleted BT549 or SUM149 cells (Supplementary Figure S4d, top). We then considered the possibility of ERα protein degradation.39 Indeed, combination of a proteosome inhibitor, MG-132, and 5-AZA allowed detection of ERα expression (Supplementary Figure S4d, bottom). The detected ERα protein expression was higher in FOXC1-depleted BT549 cells relative to vector control. Notably, no ERα protein expression was seen in SUM149 cells under the same treatment condition as BT549 cells (data not shown). There may be an unknown regulatory mechanism responsible for ERα silencing in SUM149 cells.

The forkhead domain (FHD) of FOXC1 is essential for the blockage of GATA3 binding to the CREs of ERα

FOXC1 contains several known functional domains: N- and C-terminal trans-activation domains (AD-1 and AD-2), a FHD, and a transcriptional inhibitory domain (ID).40 The FHD is a highly conserved DNA-binding domain and missense mutations in the FHD impair the DNA binding ability of many FOX family proteins including FOXC1.41 In order to determine if the FHD is crucial for the interaction between FOXC1 and the regulatory regions of ERα, we constructed and transfected Myc-tagged truncated fragments of FOXC1 which contain AD1 alone (Construct #1), AD1 and FHD (Construct #2), or FHD alone (Construct #3) into MCF-7 cells (Figure 4a). Quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting showed that only the sequences containing an intact FHD such as full length FOXC1 and Constructs #2 and #3 inhibited ERα expression at both mRNA (Figure 4b, left) and protein levels (Figure 4c). In addition, only the full length FOXC1 retained the ability to inhibit GATA3 (Figure 4b, right and Figure 4c). Because AD-1 alone was not detected in immunoblotting (Figure 4c, left), we generated an AD-1-GFP fusion protein, Construct #1-GFP (Figure 4c, right). Consistent with these findings, the ERE-luciferase reporter assays indicated that the full length protein and Constructs #2 and #3 were able to repress ERα transcriptional activity (Figure 4d). We further conducted a ChIP assay to determine if the FHD alone is capable to compete with GATA3 for DNA binding. FHD overexpression profoundly enhanced its interaction with both enhancer 1 and promoter C, and this interaction also effectively prohibited GATA3 from binding to the same DNA regions (Figure 4e). This result is in agreement with a previous study that the expression of the FHD alone is sufficient to bind DNA in a sequence-specific manner.31 Collectively, our data show that the FHD of FOXC1 is sufficient for competition with GATA3 for DNA binding.

Figure 4. FOXC1 interacts with the CREs of the ERα gene via FHD.

(a) A structural diagram represents the domains of the full length (FL) and truncated fragments of FOXC1. MCF-7 cells were transfected with vector, FL, or truncated fragments: (b) mRNA and (c) protein expression of ERα and GATA3 was measured. Anti-Myc or anti-GFP antibodies were used to detect the expression of the constructs. (d) MCF-7 was transfected with an ERE-driven-luc reporter with vector or FOXC1 constructs. The DNA binding capacity of ERα was determined by luciferase assays. (e) Cell lysates from MCF-7 transfected with vector or Construct #3 were obtained and subjected to ChIP analysis. Anti-Myc and anti-GATA3 antibodies were used to measure the binding signals. ****, P<0.0001; ***, P<0.001; *, P<0.05.

FOXC1-induced ERα silencing is associated with endocrine resistance in breast cancer cells

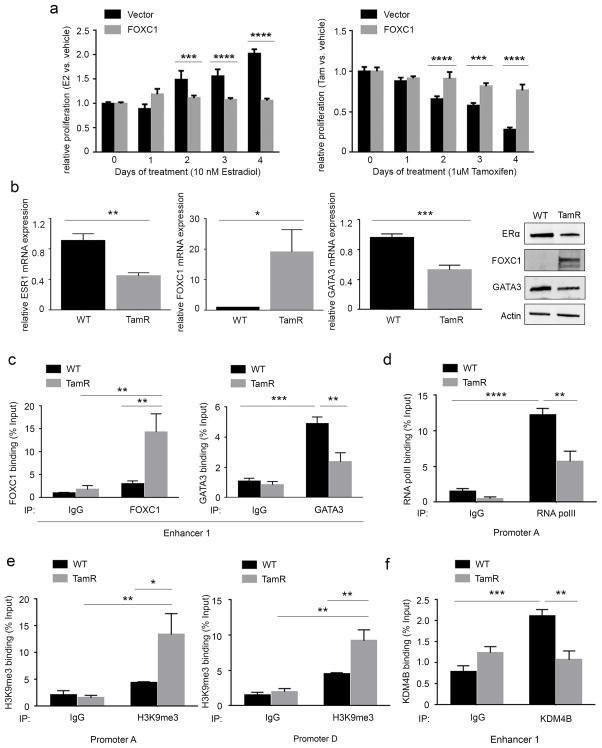

In light of the above findings, we postulated that FOXC1 alters the sensitivity of ERα-positive breast cancer cells to estrogen or antiestrogen treatment. Cell proliferation assays indicated that stable FOXC1-overexpression in MCF-7 cells considerably impeded both the growth-stimulatory effect of β-estradiol (Figure 5a, left) and the growth-inhibitory effect of tamoxifen (Figure 5a, right) and fulvestrant (Supplementary Figure S5a). These data suggest that the downregulation of ERα by FOXC1 enables ERα-positive cells to be less dependent on β-estradiol and more resistant to antiestrogen treatment. Due to possibly ERα-independent tamoxifen toxicity,42 we performed an apoptosis assay to measure the viable cells (Annexin V and PI negative) in vector- and FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 cells when treated with tamoxifen. The vector group treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen maintained a similar proportion of viable cells (86.5%±2.8% vs. 85.9%±3.4%). Similar results were observed in FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 cells treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen (94.2%±1.2% vs. 92.4%±1.6%) (Supplementary Figure S5b). Thus the observed inhibition of cell growth by tamoxifen was not due to reduced cell viability. We then generated in vitro-derived tamoxifen-resistant (TamR) MCF-7 cells and compared the expression of ERα, FOXC1, and GATA3 in the wild type (WT) and TamR MCF-7 cells. Both protein and mRNA levels of ERα decreased while the levels of FOXC1 increased in TamR relative to WT cells (Figure 5b). Consistent with a previous study,43 we showed that the expression of GATA3 was moderately reduced in TamR relative to WT MCF-7 cells (Figure 5b). Moreover, analysis of a publicly available microarray dataset44 revealed that FOXC1 mRNA expression in TamR cells was significantly higher relative to TamS cells in response to different treatments (β-estradiol and tamoxifen) targeting ER. However, no difference was found in GATA3 mRNA levels between the two groups (Supplementary Figure S5c). Given the interplay between FOXC1, ERα, and GATA3, we lastly wanted to know if the proposed inhibitory mechanism also involved in endocrine resistance. Similar to what we have observed in MCF-7 and BT549 cells, the increased interaction between FOXC1 and enhancer 1 was associated with reduced GATA3 binding in TamR MCF-7 cells (Figure 5c). Enhanced RNA polII recruitment at promoter A was detected (Figure 5d). In addition, less KDM4B binding at enhancer 1 as well as elevated H3K9me marks at promoter A and D were observed (Figure 5e and 5f). These results strongly indicate that the FOXC1-driven ERα silencing is relevant in endocrine resistant breast cancer cell lines.

Figure 5. FOXC1 in endocrine resistant breast cancer cells.

(a) MCF-7 cells stably transfected with vector or FOXC1 were cultured in phenol red-free DMEM containing 5% dextran-coated charcoal stripped serum (DCC-serum) for 24 hours and then treated with 10 nM estradiol (left) or 1 uM tamoxifen (right) for 4 days. Cell proliferation was measured by MTT assays. (b) TamR MCF-7 cells were generated as described in the Materials and Methods. The mRNA expression of ERα (first panel), FOXC1 (second panel), and GATA3 (third panel) as well as the protein expression (fourth panel) was compared by qRT-PCR or immunoblotting. In WT and TamR MCF-7 cells, the bindings of (c, left) FOXC1, (c, right) GATA3, (d) RNA polII, (e) H3K9me3, and (f) KDM4B to the regulatory regions of ERα were subjected to ChIP-qPCR analysis. ****, P<0.0001; ***, P<0.001; **, P<0.01; *, P<0.05.

FOXC1 is associated with acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancers

To further strengthen the role of FOXC1 in endocrine resistance, we performed immunohistochemistry staining of FOXC1 and GATA3 in 10 relapsed breast cancers from patients with primary ERα-positive tumors treated with tamoxifen. As illustrated in Figure 6a, FOXC1 was not detected in any of (0 of 4) the patients whose recurrent tumors retained consistent ERα expression, but was prevalent (67%, 4 of 6) in the patients whose recurrent tumors expressed reduced or no ER. We observed GATA3 labeling in 75% (3 of 4) of the recurrent ER-reduced/negative but FOXC1-positive tumor samples. A previous study showed that GATA3 staining was found in all of the luminal loss metastases (Metastatic tumors which completely lost ER and/or PR expression from the primary ER and/or PR-positive luminal tumors.).34 Although the FOXC1 status of those luminal loss metastatic tumors was not mentioned in the study, the presence of GATA3 in ER-negative tumor suggests a possibility that the proposed ERα inhibitory mechanism is involved in the triple-negative or the recurrent ERα-negative breast cancers. Importantly, strong and highly prevalent FOXC1 staining was observed in the nuclei of tumor cells from recurrent ER-negative or reduced tumors, whereas the staining in the recurrent ER-positive tumors was undetectable (Figure 6b). Diffuse nuclear GATA3 staining was observed independent of FOXC1 or ERα expression (Figure 6b). These results demonstrate that FOXC1 is associated with acquired endocrine resistance in human ER-positive breast cancer.

Figure 6. ERα, FOXC1, and GATA3 expression in recurrent endocrine resistant breast cancers.

(a) A summary of ERα, FOXC1, and GATA3 immunohistochemistry results in primary and recurrent human breast cancer. Three cut-off values of the H-score were used to define FOXC1 status in recurrent tumors. −, <20; +, 20–100; ++, 101–200; +++, >200. (b) Sections of recurrent ER-positive (left) and ER-negative (right) tumor were stained with anti-FOXC1 or anti-GATA3 antibodies. High-magnification (x400) images of representative staining were shown. (c) A schematic diagram illustrates the suppression of ERα by FOXC1 in breast cancer. Left, in FOXC1-low breast cancer, the interaction between GATA3 protein and the ERα gene facilitates a series of transcriptional events, such as recruitment of Pol II, that lead to the transcription of ERα. Right, in FOXC1-high breast cancer, FOXC1 blocks GATA3 from binding to the shared regions in the CREs of ERα gene, therefore prohibiting Pol II recruitment and increasing histone methylation that together result in less transcription of ERα.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have revealed a novel FOXC1-mediated signaling pathway responsible for ERα silencing in breast cancer. We show that expression of FOXC1, a transcription factor essential for mesoderm tissue development in vertebrates40, 41 and a marker for BLBC,14 inhibits ERα expression and activity by interfering with GATA3 binding to the CREs of ERα. Moreover, overexpression of FOXC1 blocks the interaction between GATA3 and the CREs of ERα gene, mitigates the recruitment of Pol II, increases the histone methylation at ERα promoters, and thereby suppresses ERα expression and transcriptional activity (Figure 6c).

We suspect that FOXC1-DNA binding leads to the modification of chromatin structure. In fact, we demonstrate that FOXC1 interacts with the CREs of the ERα gene via the FHD, which is known to bend DNA at an angle of ~94° upon binding.45 GATA3 positively regulates ERα by shaping ERα enhancer accessibility.46 In other words, GATA3 binding to the ERα enhancer region regulates downstream ERα promoter activity via long-range enhancer-promoter interactions.35, 36 Given our result, it is possible that the recruitment of FOXC1/GATA3 to enhancer 1 and promoter C induces DNA conformational changes that affect the accessibility of RNA polII, H3K9me3, and KDM4B to promoter A and D. Interestingly, although the FHD alone is enough to repress ERα, the full length FOXC1 is most effective in regulating ERα than the truncated forms. This can be attributed to the finding that both the N-terminal (AD-1) and C-terminal (AD-2) transcriptional activation domains are required for full activity of FOXC1.40 Whether the ID can interact with other nuclear proteins to modulate FOXC1 activity remains to be determined. The inhibitory domain (ID) is located at the central region of FOXC1 protein and is able to reduce the trans-activation potential of AD-2.40 To our knowledge, the role of ID and AD2 in the repression of other genes has not been revealed. Of note, we have recently demonstrated that FOXC1 induces Gli2 DNA binding by directly interacting with Gli2 via the AD1 domain of FOXC1.25

Multiple studies have already suggested the connection between ERα and FOX family proteins. FOXA1 opens up chromatin structure and facilitates ERα-chromatin interactions6 and is necessary for ERα expression.47 FOXO3A and FOXM1 interact with the ERα promoter and transcriptionally activate ERα.26, 27 Eeckhoute and colleagues have identified a positive cross-regulatory loop between GATA3 and ERα in which ERα also transcriptionally activates GATA3.7 Therefore, the dropped expression level of GATA3 might also be caused by the repression of ERα. We do not identify any consensus sequence of other ERα regulators, i.e. FOXA1, near the three FOXC1 sites. However, FOXC1 may also interact with other regulatory molecules at regions that were not tested in this study. It is worth mentioning that we observed an increase of FOXO1 protein level in FOXC1-overexpressing cells, which is consistent with a previous report that FOXC1 transcriptionally activates FOXO1 in response to cellular stress in eyes.48

GATA3 and KDM4B are found to function as part of the same transcriptional regulatory complex to upregulate ERα.37 Hence we believe FOXC1 interferes with GATA3 binding and thereby decreases the recruitment of KDM4B-GATA3 complex to the regulatory regions of ERα gene. All these events will lead to enrichment of H3K9me3 marks and decreased ERα expression in FOXC1-overexpressing MCF-7 cells. However, we were not able to detect any KDM4B protein expression or KDM4B recruitment to ERα promoters in BT549 cells (data not shown). A recent study claimed that the amplification and overexpression of KDM family proteins KDM4A, C, and D are more prevalent in BLBC, while KDM4B overexpression is more predominant in luminal breast cancer.49 Therefore it is possible that KDM4B is a regulator of ERα signaling in luminal breast cancer while other KDM subfamily proteins are involved ERα regulation in BLBC. In fact, the FOXC1-induced enrichment of H3K9me3 could be GATA3 irrelevant. FOXC1 might form an in vivo protein complex with histone methyltransferase and incorporate the enzyme into the interaction with ERα promoters. It is also possible that the changed DNA conformation upon FOXC1 binding renders ERα promoters more accessible to histone methyltrasferase.

Interestingly, we show that increased FOXC1 expression attenuates the response of ER-positive breast cancer cells to estrogen and tamoxifen treatment. In addition, FOXC1 is prevalent in patients whose relapsed tumors have reduced or lost ER expression. Considering the importance of ER in endocrine therapy, our results shed light on a possible explanation for the altered receptor status in patients with relapsed tumors and acquired resistance.11 This study warrants further investigation of FOXC1 in endocrine resistance using a larger sample set. In conclusion, this study offers new mechanistic insight into ERα regulation during breast cancer progression and implicates targeting FOXC1 as a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of endocrine-resistant and recurrent breast cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and chemicals

Human breast cancer cell lines used in this study were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. The authenticity of the MCF-7, BT549, and SUM149 cell lines was confirmed using the Short Tandem Repeat (STR) method (Laragen Inc., Culver City, CA) and tested for mycoplasma contamination. Tamoxifen resistant cell lines (TamR) were generated by chronic exposure (more than 10 months) of MCF-7 cells to increasing concentrations of tamoxifen (up to 10 μM in ethanol) in routine cell culture. 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-AZA, 20 uM), 17β-estradiol (10 nM), tamoxifen (1 uM), and fulvestrant were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Statistical Analysis

Results represent mean ± s.d. of three independent experiments. Statistically analyses were performed with unpaired two-tailed t test for in vitro studies (****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; and *, P < 0.05). P-value <0.05 was considered as significant. The bar graphs were plotted by Prism GraphPad software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA151610), the Avon Foundation for Women (02-2014-063), and David Salomon Translational Breast Cancer Research Fund to Xiaojiang Cui, the Fashion Footwear Charitable Foundation of New York, Inc., Associates for Breast and Prostate Cancer Studies, the Margie and Robert E. Petersen Foundation, and the Linda and Jim Lippman Research Fund to Armando Giuliano.

We thank Dr. Julia Gee for discussion about antiestrogen experiments.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Xiaojiang Cui is a named inventor for patent applications regarding the role of FOXC1 in cancer. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sparano JA, Fazzari M, Kenny PA. Clinical application of gene expression profiling in breast cancer. Surgical oncology clinics of North America. 2010;19:581–606. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborne CK. Steroid hormone receptors in breast cancer management. Breast cancer research and treatment. 1998;51:227–238. doi: 10.1023/a:1006132427948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badve S, Dabbs DJ, Schnitt SJ, Baehner FL, Decker T, Eusebi V, et al. Basal-like and triple-negative breast cancers: a critical review with an emphasis on the implications for pathologists and oncologists. Modern pathology: an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2011;24:157–167. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Ross-Innes CS, Schmidt D, Carroll JS. FOXA1 is a key determinant of estrogen receptor function and endocrine response. Nature genetics. 2011;43:27–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eeckhoute J, Keeton EK, Lupien M, Krum SA, Carroll JS, Brown M. Positive cross-regulatory loop ties GATA-3 to estrogen receptor alpha expression in breast cancer. Cancer research. 2007;67:6477–6483. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manavathi B, Samanthapudi VS, Gajulapalli VN. Estrogen receptor coregulators and pioneer factors: the orchestrators of mammary gland cell fate and development. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2014;2:34. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2014.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida T, Eguchi H, Nakachi K, Tanimoto K, Higashi Y, Suemasu K, et al. Distinct mechanisms of loss of estrogen receptor alpha gene expression in human breast cancer: methylation of the gene and alteration of trans-acting factors. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:2193–2201. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.12.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma Y, Fan S, Hu C, Meng Q, Fuqua SA, Pestell RG, et al. BRCA1 regulates acetylation and ubiquitination of estrogen receptor-alpha. Molecular endocrinology. 2010;24:76–90. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuukasjarvi T, Kononen J, Helin H, Holli K, Isola J. Loss of estrogen receptor in recurrent breast cancer is associated with poor response to endocrine therapy. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1996;14:2584–2589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.9.2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kume T, Deng KY, Winfrey V, Gould DB, Walter MA, Hogan BL. The forkhead/winged helix gene Mf1 is disrupted in the pleiotropic mouse mutation congenital hydrocephalus. Cell. 1998;93:985–996. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen TW, Ray T, Wang J, Li X, Naritoku WY, Han B, et al. Diagnosis of Basal-Like Breast Cancer Using a FOXC1-Based Assay. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015:107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray PS, Wang J, Qu Y, Sim MS, Shamonki J, Bagaria SP, et al. FOXC1 is a potential prognostic biomarker with functional significance in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer research. 2010;70:3870–3876. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia L, Huang W, Tian D, Zhu H, Qi X, Chen Z, et al. Overexpression of forkhead box C1 promotes tumor metastasis and indicates poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57:610–624. doi: 10.1002/hep.26029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Shao QS, Yao HB, Jin Y, Ma YY, Jia LH. Overexpression of FOXC1 correlates with poor prognosis in gastric cancer patients. Histopathology. 2014;64:963–970. doi: 10.1111/his.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei LX, Zhou RS, Xu HF, Wang JY, Yuan MH. High expression of FOXC1 is associated with poor clinical outcome in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2013;34:941–946. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultz JR, Petz LN, Nardulli AM. Estrogen receptor alpha and Sp1 regulate progesterone receptor gene expression. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2003;201:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohammed H, D’Santos C, Serandour AA, Ali HR, Brown GD, Atkins A, et al. Endogenous purification reveals GREB1 as a key estrogen receptor regulatory factor. Cell reports. 2013;3:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sengupta S, Sharma CG, Jordan VC. Estrogen regulation of X-box binding protein-1 and its role in estrogen induced growth of breast and endometrial cancer cells. Hormone molecular biology and clinical investigation. 2010;2:235–243. doi: 10.1515/HMBCI.2010.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross-Innes CS, Stark R, Holmes KA, Schmidt D, Spyrou C, Russell R, et al. Cooperative interaction between retinoic acid receptor-alpha and estrogen receptor in breast cancer. Genes & development. 2010;24:171–182. doi: 10.1101/gad.552910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caizzi L, Ferrero G, Cutrupi S, Cordero F, Ballare C, Miano V, et al. Genome-wide activity of unliganded estrogen receptor-alpha in breast cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:4892–4897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315445111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prest SJ, May FE, Westley BR. The estrogen-regulated protein, TFF1, stimulates migration of human breast cancer cells. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2002;16:592–594. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0498fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Augereau P, Badia E, Fuentes M, Rabenoelina F, Corniou M, Derocq D, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the human NRIP1/RIP140 gene by estrogen is modulated by dioxin signalling. Molecular pharmacology. 2006;69:1338–1346. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han B, Qu Y, Jin Y, Yu Y, Deng N, Wawrowsky K, et al. FOXC1 Activates Smoothened-Independent Hedgehog Signaling in Basal-like Breast Cancer. Cell reports. 2015;13:1046–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madureira PA, Varshochi R, Constantinidou D, Francis RE, Coombes RC, Yao KM, et al. The Forkhead box M1 protein regulates the transcription of the estrogen receptor alpha in breast cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:25167–25176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo S, Sonenshein GE. Forkhead box transcription factor FOXO3a regulates estrogen receptor alpha expression and is repressed by the Her-2/neu/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:8681–8690. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8681-8690.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnani L, Ballantyne EB, Zhang X, Lupien M. PBX1 genomic pioneer function drives ERalpha signaling underlying progression in breast cancer. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, Azorsa DO, Tanner MM, Guan XY, et al. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1997;277:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pugh BF, Tjian R. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by Sp1: evidence for coactivators. Cell. 1990;61:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierrou S, Hellqvist M, Samuelsson L, Enerback S, Carlsson P. Cloning and characterization of seven human forkhead proteins: binding site specificity and DNA bending. The EMBO journal. 1994;13:5002–5012. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kos M, Reid G, Denger S, Gannon F. Minireview: genomic organization of the human ERalpha gene promoter region. Molecular endocrinology. 2001;15:2057–2063. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.12.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marconett CN, Sundar SN, Poindexter KM, Stueve TR, Bjeldanes LF, Firestone GL. Indole-3-carbinol triggers aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent estrogen receptor (ER)alpha protein degradation in breast cancer cells disrupting an ERalpha-GATA3 transcriptional cross-regulatory loop. Molecular biology of the cell. 2010;21:1166–1177. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cimino-Mathews A, Subhawong AP, Illei PB, Sharma R, Halushka MK, Vang R, et al. GATA3 expression in breast carcinoma: utility in triple-negative, sarcomatoid, and metastatic carcinomas. Human pathology. 2013;44:1341–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartkuhn M, Renkawitz R. Long range chromatin interactions involved in gene regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:2161–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bulger M, Groudine M. Enhancers: the abundance and function of regulatory sequences beyond promoters. Dev Biol. 2010;339:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaughan L, Stockley J, Coffey K, O’Neill D, Jones DL, Wade M, et al. KDM4B is a master regulator of the estrogen receptor signalling cascade. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:6892–6904. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shenker NS, Flower KJ, Wilhelm-Benartzi CS, Dai W, Bell E, Gore E, et al. Transcriptional implications of intragenic DNA methylation in the oestrogen receptor alpha gene in breast cancer cells and tissues. BMC cancer. 2015;15:337. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1335-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nawaz Z, Lonard DM, Dennis AP, Smith CL, O’Malley BW. Proteasome-dependent degradation of the human estrogen receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berry FB, Saleem RA, Walter MA. FOXC1 transcriptional regulation is mediated by N- and C-terminal activation domains and contains a phosphorylated transcriptional inhibitory domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:10292–10297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saleem RA, Banerjee-Basu S, Murphy TC, Baxevanis A, Walter MA. Essential structural and functional determinants within the forkhead domain of FOXC1. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:4182–4193. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obrero M, Yu DV, Shapiro DJ. Estrogen receptor-dependent and estrogen receptor-independent pathways for tamoxifen and 4-hydroxytamoxifen-induced programmed cell death. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:45695–45703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becker M, Sommer A, Kratzschmar JR, Seidel H, Pohlenz HD, Fichtner I. Distinct gene expression patterns in a tamoxifen-sensitive human mammary carcinoma xenograft and its tamoxifen-resistant subline MaCa 3366/TAM. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:151–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oyama M, Nagashima T, Suzuki T, Kozuka-Hata H, Yumoto N, Shiraishi Y, et al. Integrated quantitative analysis of the phosphoproteome and transcriptome in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:818–829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.156877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saleem RA, Banerjee-Basu S, Berry FB, Baxevanis AD, Walter MA. Structural and functional analyses of disease-causing missense mutations in the forkhead domain of FOXC1. Human molecular genetics. 2003;12:2993–3005. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Theodorou V, Stark R, Menon S, Carroll JS. GATA3 acts upstream of FOXA1 in mediating ESR1 binding by shaping enhancer accessibility. Genome research. 2013;23:12–22. doi: 10.1101/gr.139469.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernardo GM, Lozada KL, Miedler JD, Harburg G, Hewitt SC, Mosley JD, et al. FOXA1 is an essential determinant of ERalpha expression and mammary ductal morphogenesis. Development. 2010;137:2045–2054. doi: 10.1242/dev.043299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berry FB, Skarie JM, Mirzayans F, Fortin Y, Hudson TJ, Raymond V, et al. FOXC1 is required for cell viability and resistance to oxidative stress in the eye through the transcriptional regulation of FOXO1A. Human molecular genetics. 2008;17:490–505. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye Q, Holowatyj A, Wu J, Liu H, Zhang L, Suzuki T, et al. Genetic alterations of KDM4 subfamily and therapeutic effect of novel demethylase inhibitor in breast cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:1519–1530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.