ABSTRACT

An increased risk of narcolepsy following administration of an AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic influenza vaccine (Pandemrix™) was described in children and adolescents in certain European countries. We investigated the potential effects of administration of the AS03-adjuvanted vaccine, non-adjuvanted vaccine antigen and AS03 Adjuvant System alone, on the central nervous system (CNS) in one-month-old cotton rats. Naïve or A(H1N1)pdm09 virus-primed animals received 2 or 3 intramuscular injections, respectively, of test article or saline at 2-week intervals. Parameters related to systemic inflammation (hematology, serum IL-6/IFN-γ/TNF-α) were assessed. Potential effects on the CNS were investigated by histopathological evaluation of brain sections stained with hematoxylin-and-eosin, or by immunohistochemical staining of microglia, using Iba1 and CD68 as markers for microglia identification/activation, albumin as indicator of vascular leakage, and hypocretin. We also determined cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hypocretin levels and hemagglutination-inhibiting antibody titers. Immunogenicity of the AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic influenza vaccine was confirmed by the induction of hemagglutination-inhibiting antibodies. Both AS03-adjuvanted vaccine and AS03 alone activated transient innate (neutrophils/eosinophils) immune responses. No serum cytokines were detected. CNS analyses revealed neither microglia activation nor inflammatory cellular infiltrates in the brain. No differences between treatment groups were detected for albumin extravascular leakage, CSF hypocretin levels, numbers of hypocretin-positive neuronal bodies or distributions of hypocretin-positive axonal/dendritic projections. Consequently, there was no evidence that intramuscular administration of the test articles promoted inflammation or damage in the CNS, or blood-brain barrier disruption, in this model.

KEYWORDS: A(H1N1)pdm09, AS03, cotton rat, narcolepsy, pandemic influenza vaccine, Pandemrix

Introduction

During the influenza pandemic in 2009, caused by a novel H1N1 virus of swine origin (further referred to as A(H1N1)pdm09 virus), approximately 31 million people received Pandemrix™,1 an inactivated, split virion A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine adjuvanted with the oil-in-water emulsion Adjuvant System AS03.2,3 The vaccine, which was manufactured by GSK, was recommended for use in adults, adolescents and children over 6 months of age.4 After the pandemic, since August 2010, the vaccine was indicated in the European Union (EU) for the prophylaxis of influenza caused by A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, and it was used in late 2010 in the United Kingdom when there was a shortage of 2010/2011 trivalent seasonal vaccine. The vaccine has not been in production since 2010, nor has it been in use after the 2010/2011 northern hemisphere winter influenza season.

An increased incidence of narcolepsy (a chronic sleep disorder, frequently accompanied by cataplexy) was observed in children and adolescents in several EU countries after administration of the vaccine.1 The lag time between A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination and the onset of narcolepsy symptoms was usually several months, but occasionally only a few days.5,6 Interestingly, an epidemiological study conducted in China revealed a seasonality in the incidence of narcolepsy, with an increase after the 2009–2010 respiratory infections season.7 Because in China, adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine was neither registered nor used, and thus only a few subjects received non-adjuvanted H1N1 vaccine, this observation led the authors to suggest that acute respiratory infections, including influenza, could be linked to narcolepsy.

Narcolepsy with cataplexy is most commonly caused by deficiency of hypocretin (also known as orexin; a neuropeptide involved in arousal and energy homeostasis), as a result of loss of hypothalamic hypocretin-producing neurons.8,9 Associations of narcolepsy with the HLA II haplotype DQB1*0602 and with DNA sequence variations in the T-cell receptor (TCR) locus have been described,8,10 suggesting that narcolepsy involves a specific HLA II-TCR interaction. One hypothesis is that the disease develops after (re)activation and expansion of T cells cross-reacting with antigen(s) from hypocretin-producing neurons, which could be triggered by environmental antigenic exposures. Such mechanism for disease development would require passage of the immune cells (and potentially secreted antibodies) to the hypothalamus. A reduction in the blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity and/or an inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS) could exacerbate such immune responses in the CNS.11 However, memory T-cell access into the CNS may also involve P-selectin-mediated trafficking through structures like the choroid plexus into the sub-arachnoid space12 and leave via meningeal lymphatic vessels as recently described in the rat13, implying that changes in BBB integrity may not be critical for T-cell trafficking.

To further investigate the association between administration of the vaccine, preceded or not by primary A(H1N1)pdm09 infection, and the narcolepsy signal, the research approach included a series of epidemiological and non-clinical (including mechanistic) studies.14 Owing to the specificity and strong HLA association, an animal model may not allow reproduction of a hypothetical pathogenic T-cell response that could be linked to narcolepsy in a way similar to that in humans, and rodent models have thus far merely been used to evaluate the effects of hypocretin deficiency.15-17 Therefore, the research approach involving animal models primarily served to explore the mechanisms underlying the potential induction of changes in the brain following vaccination, with an additional focus on possible interactions between infection and vaccination.

The four mechanistic studies presented in this article explored whether vaccination of cotton rats, preceded or not by primary A(H1N1)pdm09 infection, could induce inflammatory changes and/or cellular damage in the CNS, and/or a disruption of the BBB. The cotton rat is a recognized disease model for unadapted human influenza strains.18-21 Indeed, in a pilot study, we observed that cotton rats inoculated with wild-type A(H1N1)pdm09 virus exhibited viral replication in the lower and upper respiratory tract, accompanied by weight loss and decreased body temperature (unpublished data), and pulmonary histopathological lesions were observed in a similar, previously reported study.21 Moreover, their size is amenable to repeated hematological investigations, in contrast to that of a mouse, and allows convenient CNS histopathological evaluation. Since narcolepsy was mainly observed in children and adolescents, we used 1-month-old cotton rats to mimic this stage of human development, based on their growth curve and expected life span (approximately 12–18 months22).

We assessed several morphological correlates for brain inflammation, including microglial cell activation (a mediator of tissue damage and inflammatory processes23) and immune-cell infiltration, as well as markers of the inflammatory response by measuring serum cytokine and hematological responses. The potential for a disruption/change in the BBB integrity was assessed by evaluation of possible vascular leakage of albumin into brain structures. We also investigated narcolepsy-related parameters, including the hypocretin level in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and, by microscopic evaluation, the hypothalamic hypocretin-secreting neurons. Test articles included the AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic influenza vaccine and its individual constituents (the split virion vaccine antigen and the AS03 Adjuvant System). We conducted identical sets of experiments in animals that were either primed by intranasal inoculation with wild-type A(H1N1)pdm09 virus or left non-primed before vaccination. The treatment regimen for primed animals (2 doses) was based on the number of clinical doses plus one, while for naïve animals an extra dose was administered to compensate for the lack of specific immune memory. To match a common time-frame in which post-vaccination incident narcolepsy has been described in humans, the 2 studies evaluating the potential brain inflammation/damage were conducted over a period of 3 months after the last administration, while the 2 other studies evaluating the potential effect of BBB disruption were limited to the 72-hour period post last administration.

Results

All four studies were conducted using both A(H1N1)pdm09-primed and naïve (non-primed) 1-month-old cotton rats. Unless specified otherwise, the data obtained in the treatment groups following administration of the test articles (i.e., the AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic influenza vaccine in Studies 2 and 4, and the non-adjuvanted vaccine antigen or AS03 separately in Studies 1 and 3), were compared with the data of the corresponding naïve control group A. Overviews of the analyses conducted in vivo and at sacrifice/post-mortem are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Study designs and in vivo observations.

|

In vivo observations (Day)2 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Group (N = 24/group) | Priming1 (IN) | Treatment (IM) | Dosing (× adult-human dose) | Treatment (Day) | Body weight | WBC counts | HI Ab responses | Cytokines in serum | Sacrifice (Day)3 |

| 1# | A | naïve | saline | n.a. | 7, 21, 35 | pre, 0, 3, weekly, at sacrifice | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 38, 66, 95, 125 |

| B | naïve | H1N1 | 0.2 | 7, 21, 35 | ||||||

| C | naïve | AS03 | 0.4 | 7, 21, 35 | ||||||

| D | primed | saline | n.a. | 21, 35 | ||||||

| E | primed | H1N1 | 0.2 | 21, 35 | ||||||

| F | primed | AS03 | 0.4 | 21, 35 | ||||||

| 2 | A | naïve | saline | n.a. | 7, 21, 35 | pre, 0, 3, weekly, at sacrifice | n.a. | 38, 65, 95, 125 | n.a. | 38, 65, 95, 125 |

| B | naïve | H1N1/AS03 | 0.2 | 7, 21, 35 | ||||||

| C | primed | saline | n.a. | 21, 35 | ||||||

| D | primed | H1N1/AS03 | 0.2 | 21, 35 | ||||||

| 3 | A | naïve | saline | n.a. | 7, 21, 35 | n.a. | 35, 36, 37, 38 | n.a. | 35, 36, 37, 38 | 35, 36, 37, 38 |

| B | naïve | H1N1 | 0.2 | 7, 21, 35 | ||||||

| C | naïve | AS03 | 0.4 | 7, 21, 35 | ||||||

| D | primed | saline | n.a. | 21, 35 | ||||||

| E | primed | H1N1 | 0.2 | 21, 35 | ||||||

| F | primed | AS03 | 0.4 | 21, 35 | ||||||

| 4 | A | naïve | saline | n.a. | 7, 21, 35 | n.a. | 35, 36, 37, 38 | 38 | 35, 36, 37, 38 | 35, 36, 37, 38 |

| B | naïve | H1N1/AS03 | 0.2 | 7, 21, 35 | ||||||

| C | primed | saline | n.a. | 21, 35 | ||||||

| D | primed | H1N1/AS03 | 0.2 | 21, 35 | ||||||

1Priming was done intranasally (IN) with wild-type A/California/7/2009 virus at 104 TCID50 per animal at Day 0. 2Clinical observations were made in all studies once or twice daily. 3Days 38, 66, 95 and 125 correspond to 3 days, and 1, 2 or 3 month(s) post last dose, respectively. Days 35, 36 and 37 correspond to 6, 24, and 48 h post last dose, respectively. On each timepoint, 6 animals per group were sacrificed. #Study 1 was conducted in 2 phases (1A and 1B; N = 12/group each phase), with different days of sacrifice (Days 38 and 66 in Study 1A, and Days 95 and 125 in Study 1B). IM, intramuscular. HI Ab, antibodies measured by hemagglutination inhibition assay.

Table 2.

Observations made at sacrifice or post-mortem.

|

Post-mortem observations in brain sections |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCRT level in CSF at sacrifice | H&E staining | IHC staining for: |

||||

| Objective | Study | HCRT | albumin | CD68 & Iba1 | ||

| CNS inflammation or damage | 1 | + | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | + | + | + | − | + | |

| BBB integrity | 3 | − | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | − | + | + | + | + | |

+, assessed; -, not assessed. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. HCRT, hypocretin. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid. IHC, immunohistochemical. CNS, central nervous system. BBB, blood-brain barrier.

Clinical signs (Studies 1 and 2)

Daily recorded clinical observations indicated that none of the animals exhibited any signs of morbidity or adverse symptoms related to the infection and/or vaccination regimes. Two animals in Study 2 died of undetermined causes, of which one belonged to the naïve placebo group A and the other to the virus-primed A(H1N1)pdm09/AS03 group D. The latter animal died 42 days after priming and 7 days after the second (last) treatment. Daily observation records showed that both deceased animals had sufficient food and water and fresh bedding, and that there were no signs of dehydration or noticeable injuries related to both recorded mortalities. Based on the facility's historical data on spontaneous deaths, and considering that they occurred irrespective of priming or treatment, these isolated events were considered unrelated to treatment.

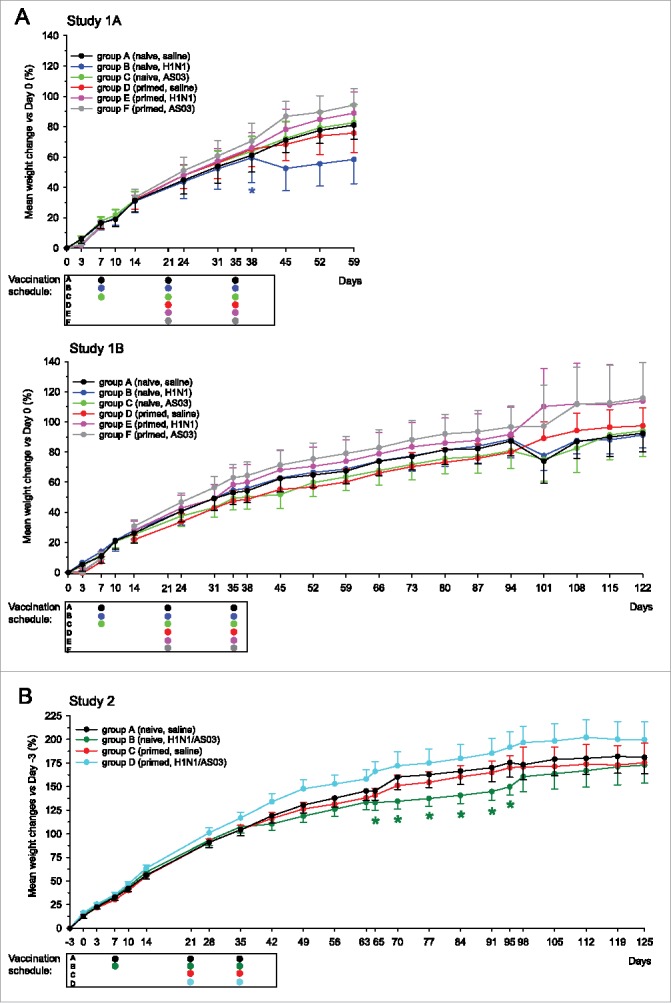

Body weights (Studies 1 and 2)

Weight curve analysis revealed a consistent average weight gain in all groups. In Studies 1A, 1B and 2, there was one, zero and one case of delay in growth, respectively. Growth was significantly delayed after the second dose (Day 38) in the naïve antigen-only group B in Study 1A, but paralleled that in the other groups from Day 45 onwards (Fig. 1A). Therefore, this was considered not biologically significant. In Study 2, a case of growth delay was observed between 1 and 2 month(s) after the last dose (Days 65–95) in the naïve A(H1N1)pdm09/AS03 group B (Fig. 1B). Given the time-point of occurrence, it was considered to be due to chance linked to the previous sacrifice of subgroups and the consecutive smaller sample size at these time-points (N = 12).

Figure 1.

Weight gain curves (Studies 1 and 2). Group mean weight gain percentages +/− the standard error of the mean (SEM) in Studies 1A and 1B (panel A) or Study 2 (panel B) were calculated relative to the average body weight at either Day 0 (the Day of priming for groups C-F in Studies 1A and 1B, or Day -3 (3 d before priming for groups C and D in Study 2). Animals were sacrificed on Days 38 and 66 in Study 1A (N = 12/group at Days 0–38, N = 6 at Days 38–59), on Days 95 and 125 in Study 1B (N = 12/group at Days 0–95, N = 6/group at Days 95–122), and on Days 38, 66, 95 and 125 in Study 2 (N = 24, 18, 12 and 6/group, at Days 0–38, 38–66, 66–95 and 95–125, respectively). No measurements were taken from groups D-F between Days 7–14 in Study 1B. The vaccination schedules below the graphs indicate the time-points of treatment per group. Significant differences between a group with the corresponding unprimed control group A are indicated by asterisks (*, p < 0.05).

Immunogenicity and systemic inflammatory responses

Hemagglutination-inhibiting antibody responses (Studies 2 and 4)

In both studies, robust hemagglutination-inhibiting (HI) antibody responses were observed after A(H1N1)pdm09/AS03 vaccination at day 38, in primed as well as naïve animals (Fig. S1). By contrast, after placebo administration, a response (albeit of low magnitude) was only observed in primed animals. This indicated that the A(H1N1)pdm09 infection as well as the vaccination were immunogenic in this model.

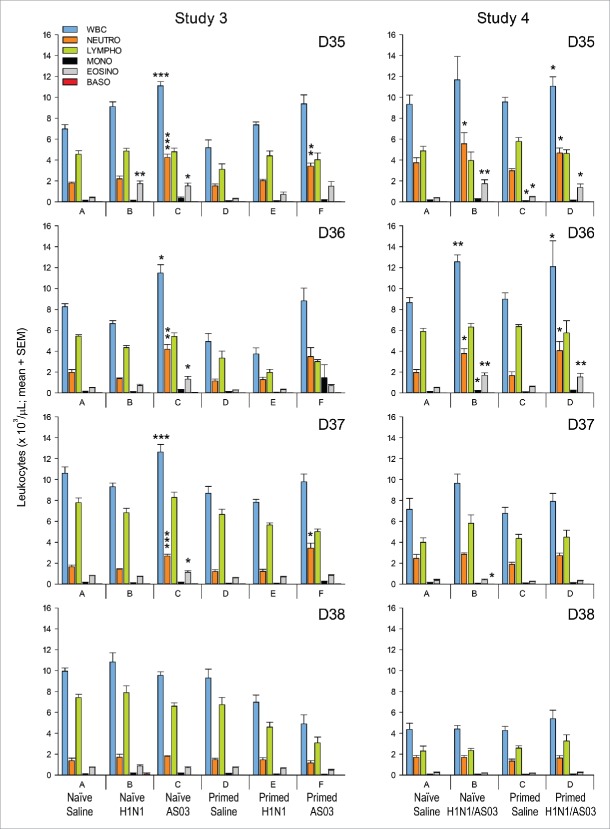

Hematology and serum cytokines (studies 3 and 4)

In the naïve treatment groups of both studies, the counts of several cell types were increased compared to the corresponding naïve control group A in the 3 d following the last administration of the adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted vaccines (i.e., 6 h, 24 h and 48 h after the last vaccination; at Day 35, 36 and 37, respectively; Fig. 2). In the vaccine antigen-only group B in Study 3, responses (comprising eosinophils) were only observed at Day 35. By contrast, in the AS03-only group C in Study 3, increased counts of neutrophils, eosinophils and total white blood cells were observed up to Day 37. Similarly, in the A(H1N1)pdm09/AS03 group B in Study 4, increased counts were observed for neutrophils and eosinophils at Day 35, for total white blood cells, neutrophils, monocytes, and eosinophils at Day 36 and for basophils at Day 37.

Figure 2.

Hematology (Studies 3 and 4). Mean counts of white blood cells (‘WBC’), neutrophils (‘NEUTRO’), lymphocytes (‘LYMPHO’), monocytes (‘MONO’), eosinophils (‘EOSINO’) and basophils (‘BASO’), expressed in 103 cell/µL were determined at 6 h, 1 day, 2 d and 3 d after the last injection (Days 35, 36, 37 and 38, respectively; N = 6/group). Significant differences between a group and the corresponding unprimed saline control group A are indicated by asterisks (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; or ***, p < 0.001). SEM, standard error of the mean.

Likewise, in the primed treatment groups, increased counts were detected for total white blood cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils at Days 35 and 36 in the A(H1N1)pdm09/AS03 group D in Study 4, and for neutrophils at Days 35 and 37 in the AS03-only group F in Study 3, while no responses were observed for the antigen-only group E in Study 3. Some responses (monocytes, eosinophils) were also detected in one of the primed control groups (i.e., in group C of Study 4, at Day 35), suggesting that the injection itself could induce a transient response.

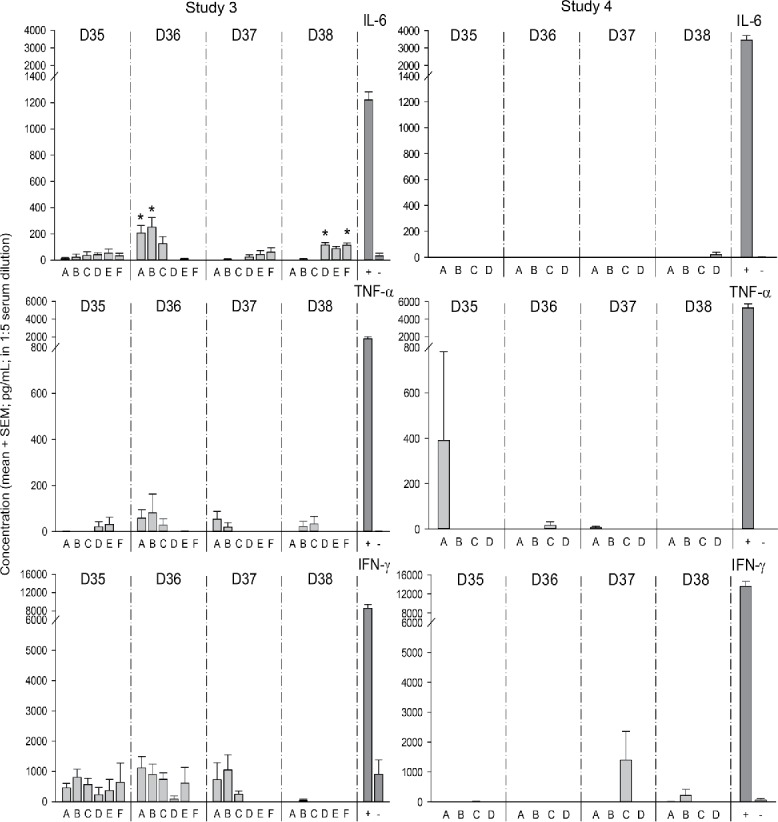

Serum cytokine (IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α) concentrations in the treatment groups were compared with concentrations in serum from unmanipulated cotton rats (negative control group). Only the IL-6 levels were significantly increased, i.e., in Study 3 at Day 36 for the naïve control and antigen-only groups A and B, and at Day 38 in the primed control and AS03-only groups D and F, respectively (Fig. 3). However, since none of the observed IL-6 levels in groups B, D and F were significantly higher than the maximum level measured in the naive control group A on various days (i.e., 207 pg/ml), these changes were considered not biologically relevant.

Figure 3.

Serum cytokine responses (Studies 3 and 4). Serum cytokine levels were measured in 1:5 serum dilution by ELISA at Days 35, 36, 37 and 38. The 1:5 dilutions of serum from unmanipulated cotton rats, with or without addition of cytokines ([IL-6] = 18 ng/ml; [TNF-α] = 32 ng/ml; [IFN-γ] = 16 ng/mL) were included as positive [‘+’] and negative [‘-‘] controls, respectively. Significance differences between a group with the corresponding negative control serum is indicated by an asterisk (*, p < 0.05).

Collectively, these results indicate that AS03, alone or combined with the antigen, induced transient innate immune responses, mainly characterized by increased counts of neutrophils and eosinophils, which had subsided by 3 d after the last injection.

Evaluation of potential CNS inflammation/damage & BBB disruption

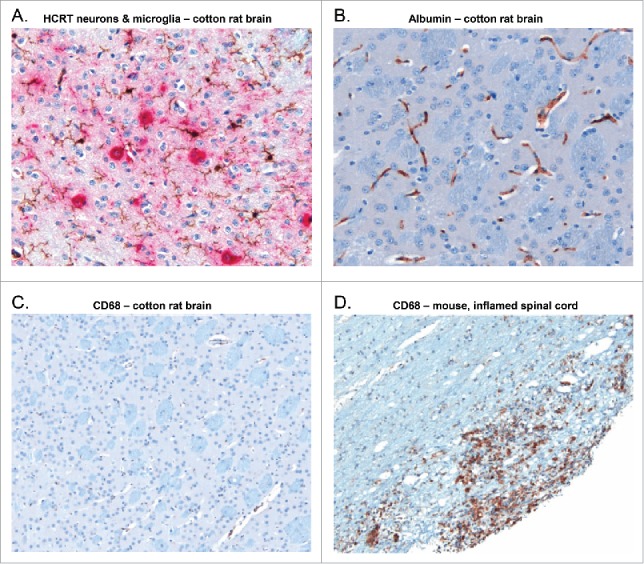

H&E, CD68 and Iba1 (all studies)

In addition to the H&E evaluation, any signs of putative inflammation were assessed by staining of brain sections for microglia, using Iba1, and microglial cell activation, using CD68. Comparisons were made with the respective naïve control group for each study. Representative slides showing brain sections stained for Iba1, CD68, hypocretin and albumin at the hypothalamic level are presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Brain sections stained for hypocretin, Iba1, CD68 or albumin at the hypothalamic level. Representative slides of the hypothalamic area from brain sections of non-primed, non-treated cotton rats (panels A-C), or of an inflamed spinal cord of a mouse (panel D) are shown. The slides were subjected to either a double sequential immunohistochemical staining targeting hypocretin (HCRT)-secreting neurons (ChromoMap Red, red staining) and Iba1 (ChromoMap DAB; brown staining; panel A), or to a single immunohistochemical staining targeting either albumin (DAB Map; brown staining; panel B), or CD68 (ChromoMap DAB, brown staining; panels (C)and D). As there was no signal detected from naïve cotton rat brain, the CD68 staining was demonstrated on an inflamed spinal cord of a mouse.

No treatment-related inflammatory lesions were observed in the H&E-stained sections. Across the groups in Studies 1 and 3, minimal, grade 1 microgliosis was observed in some H&E-stained sections, however very few (8/285) specimens showed subjectively discernible increases in the number of Iba1-positive microglia compared to the naïve control groups (data not shown). In Studies 2 and 4, no increase in the number of Iba1-positive microglia was observed in any treated group. Based on evaluation of the anti-CD68-stained sections, no evidence of activated microglial cells in the hypothalamus was found in any study. Overall, no inflammatory lesions or striking differences in staining features between groups were observed.

Albumin (Studies 3 and 4)

BBB integrity was assessed by staining of brain sections for albumin, used here as a marker of abnormally increased vascular permeability.

No extravascular albumin staining was observed in any of the specimens evaluated.

Evaluation of narcolepsy-related parameters

Immunohistochemical evaluation of hypocretin-secreting neurons in brain sections (all studies)

Following immunohistochemical staining of brain sections, including the hypothalamus, for hypocretin, the numbers of hypocretin-positive neuronal bodies and the intensity/extent of hypocretin-positive axonal and dendritic projections were graded on a 3-point or a 4-point system, respectively (with grade 1 corresponding to the lowest number or lowest staining intensity/distribution, respectively; see Methods). Results are presented in Tables S1 and S2.

For the evaluation of hypocretin-positive staining features, scoring results were similar across groups, i.e., mainly grade 2 or 3 for the numbers of hypocretin-positive neuronal bodies, and mainly grade 3 for the distribution and staining intensity of hypocretin-positive axonal and dendritic projections. This suggests that the priming and treatment regimens had no effect on the number of hypocretin-secreting neurons or distribution of hypocretin-positive axonal and dendritic projections.

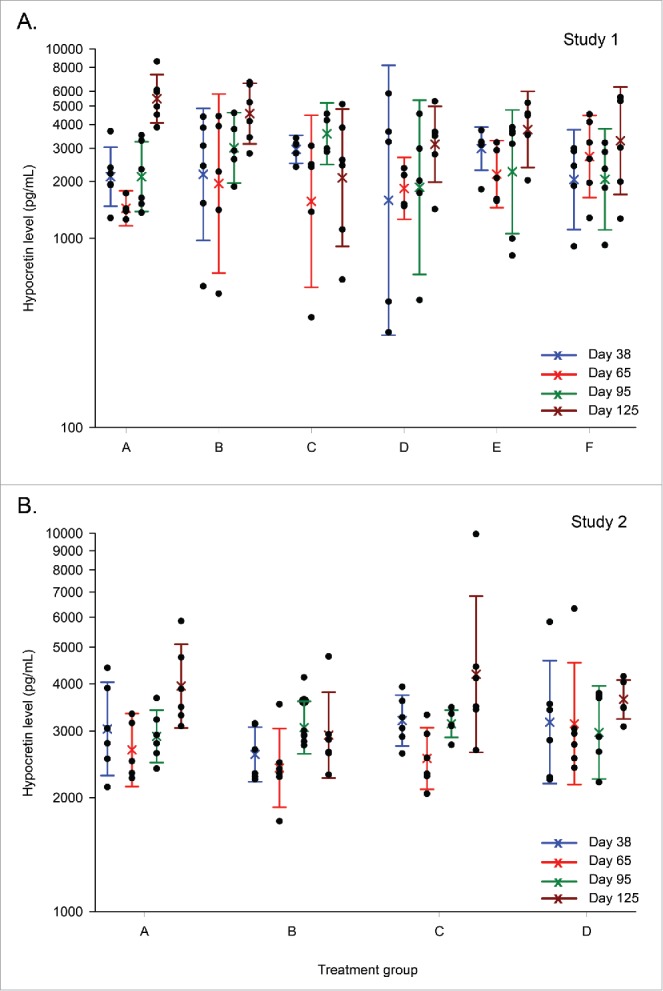

CSF hypocretin levels (Studies 1 and 2)

In both studies, CSF hypocretin levels in the treatment and control groups were not significantly different at any time-point measured (i.e., 3 d and 1, 2 and 3 months after the last injection; Fig. 5). When the mean levels in both studies were compared between time-points (irrespective of groups), there was a trend for an 1.2 to 2.1-fold increase at Day 125 compared to the preceding time-points, which was statistically significant in Study 1 (p ≤ 0.032). This was considered of no biological relevance.

Figure 5.

Hypocretin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (Studies 1 and 2). Distribution graphs of hypocretin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are presented for Days 38, 65, 95 and 125 (3 d or 1, 2, or 3 months after the last injection). Distribution (first and third quartiles) and means are represented by colored bars and open circles, respectively. Individual measurements (N = 6/group per time-point) are represented by black dots. In Study 1, groups A, B and C include naïve animals treated with saline, A(H1N1)pdm09 antigen, or AS03, respectively, and groups D, E and F include virus-primed animals treated with saline, A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine antigen, or AS03, respectively (panel A). In Study 2, groups A and B include naïve animals treated with saline or AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine, and groups C and D include virus-primed animals treated with saline or AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine, respectively (panel B).

Discussion

Pandemrix™ vaccination has been associated with an increased incidence of narcolepsy in children and adolescents in certain EU countries.1 We used the cotton rat model to evaluate any potential effects on the CNS and BBB integrity after administration of the AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic influenza vaccine, the vaccine antigen alone, and AS03 alone. These respective test articles were administered in volumes that constituted 1/5th, 1/5th or 2/5th of the adult-human doses, corresponding on a body-weight basis to 123, 123 or 246 times the equivalent pediatric dosages, or 215, 215 or 430 times the equivalent dosages for adults, respectively (based on a 20-kg child, a 70-kg adult, and a 65-g young cotton rat [the average animal weight in the current study]). We also evaluated the effects of virus infection preceding vaccination in this model. Because there is no animal model for the induction of narcolepsy, we focused on the evaluation of the potential effects of the adjuvanted vaccine and its 2 distinct components on various clinical, biochemical, and morphological parameters that would be indicative of damage/inflammation in the CNS or disruption of the BBB. Though immune cells derived from peripheral blood can be present in the CNS or CSF of healthy individuals 12,24, it is thought that a disruption in BBB integrity or inflammation in the CNS, while probably not critical for T-cell entry, could at least facilitate the direct entrance of immune cells into the CNS.11

Our results showed that both AS03 alone and the adjuvanted vaccine activated transient innate immune responses. However, no evidence of microglia activation, CNS inflammatory cellular infiltrates, neuronal degeneration, reduction of the number of hypocretin-positive neurons in the hypothalamus, or of extravascular albumin leakage was observed, suggesting that none of the test articles were able to induce CNS inflammation/damage or disruption of the BBB in naïve or primed cotton rats. In addition, the hypocretin levels in the CSF were unaffected by the treatments.

One of the 24 virus-primed A(H1N1)pdm09/AS03-treated animals died of an undetermined cause. However, we observed no morbidity, weight loss or other adverse clinical signs that were considered related to virus infection or vaccination, nor were there any potentially detrimental conditions with respect to food and water supply or housing that could explain this event. It has been reported that infection of cotton rats with unadapted human H1N1 or A(H1N1)pdm09 virus can result in an inflammatory response in the lung,21 tachypnea, and weight loss.25 In our study, the weight curves of primed and naïve animals before vaccination were similar. This was not unexpected because in our preliminary infection-dose finding investigations in this model, the observed weight loss was marked (∼15%) with the highest dose of 106 TCID50/100 μl, but less pronounced (∼5%) with the same dose as used in the current study, i.e., 104 TCID50/100 μl (data not shown). The latter priming dose was then selected based on the observed favorable viral replication, as detected in nasal wash samples. Since in this preliminary study, only weight loss and decreased temperature were reported with any of the doses assessed, the absence of clinical signs following priming in the current study was not necessarily suggestive of a suboptimal priming procedure.

The absence of alterations in the CNS reinforces the low probability of any potential direct effect of the vaccine constituents on the brain. In a previous study in mice injected intramuscularly with AS03-adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine, the biodistribution of the H5N1 vaccine antigen alone or combined with AS03, and of individually labeled AS03 constituents (α-tocopherol, squalene and polysorbate-80) was investigated.26 Up to 3 d after the injections (the last timepoint analyzed), only polysorbate-80 was detected in the brain, albeit at very low levels (<1% of the injected dose; with the AS03 dose on a body-weight basis being comparable [1.2 or 1.5 times lower] to that used in the current study). It is noted that the mice in these analyses were not perfused for removal of residual blood that may have contained polysorbate-80, which has biased its quantification in the brain tissue.

In human narcoleptic patients, lack of or reduced detection of hypocretin in the CSF is a consistent feature. Similarly, in mice, hypocretin neuronal activity regulates the maintenance of wakefulness,27,28 and transgenic mice with no hypocretin-containing neurons showed symptoms similar to those observed in human narcolepsy.29 We therefore hypothesized that decreased hypocretin levels in the CSF of cotton rats could serve as a proxy for an increased risk of putative vaccination-associated narcolepsy development in humans. In our study, priming and/or vaccination did not result in decreased CSF hypocretin levels. Furthermore, we found no evidence of treatment- or priming-induced variations in the numbers of hypothalamic hypocretin-positive neuronal bodies or the distribution and staining intensity of hypocretin-positive axonal or dendritic projections within the CNS. Clearly, these studies are confounded by the rare nature of this narcolepsy signal in humans, as well as the specific genetic background linked to narcolepsy, which includes the HLA-DQ-0602 allele. Additionally, intrinsic limitations of this preclinical research model preclude extrapolation of the current data to exclude that hypocretin deficiency and loss of hypocretin-secreting neurons could occur after similar priming and vaccination conditions in humans.

Innate immune activation by AS03 alone and AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza vaccine was demonstrated by the hematology data. Owing to the inflammatory response following vaccination, we detected rapid transient changes in the total white blood cell count (characterized mainly by neutrophils and eosinophils) up until 2 d after injection of AS03 or AS03-adjuvanted vaccine. The vaccine antigen alone, by contrast, did not induce any total white blood cell variations beyond 6 h post-vaccination. Consistently, AS03 has previously been shown to stimulate innate immune responses without being associated with an antigen.30 In addition, recent data showed that retention at the injection site was shorter-lived for an H5N1 antigen alone than for the antigen combined with AS03.26 The pattern of activation was also consistent with our current understanding of the mode of action of AS03. In mice and rabbits, the mixed-cell type inflammatory response observed at the injection site within 3 d of AS03 administration was followed by draining lymph node activation and a transient increase in the systemic neutrophil level.26,30,31 This was accompanied by proinflammatory cytokine responses at the injection site and in the draining lymph node.30 In the current studies, no systemic cytokine (IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α) responses were observed. This was unexpected considering the kinetics of early cytokine responses to vaccination.30,32,33 A likely explanation is that their spillover from the draining lymph node into the serum was too low to be detected. We did however observe changes in the counts of specific cell types such as neutrophils, reproducing earlier findings in mice and rabbits.26,31 This indicated that the AS03-adjuvanted vaccine induced innate immune responses. In turn, these responses activated adaptive immune responses, as evidenced by the HI antibody responses to the adjuvanted vaccine.

In a recent publication, Tesoriero et al used an immunodeficient mouse model to study the effects of H1N1 influenza infection on the CNS, and the hypothalamus in particular, and established for the first time a model of H1N1 infection-induced narcolepsy.34 RAG-1 knock-out mice were intranasally infected with the WSN/33 neuro-adapted strain of H1N1 influenza virus. Viral replication was shown in the lateral hypothalamus, and correlated inversely with the presence of hypocretin-secreting neurons. In several cases, viral replication was observed in hypocretin-secreting neurons. The infected mice developed narcolepsy-like symptoms that closely resembled those of hypocretin- or hypocretin receptor-deficient mice. It seems likely that the loss of hypocretin-secreting neurons was associated with viral replication and triggered the appearance of narcolepsy-like symptoms. This publication established migration of the neuro-adapted H1N1 influenza virus to neurons with involvement of the olfactory bulb and resulting in narcolepsy-like symptoms. However, when interpreting these results, it is important to consider that the neuro-adapted H1N1 strain that was used differs from the A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza virus in HA glycosylation patterns.35 Furthermore, the immuno-deficient nature of the mouse model may have facilitated detection of viral neurotropism due to a more extensive viral replication, which also made this model unsuitable for evaluating the potential role of vaccine/virus–induced immune responses. Normal adaptive immune responses, e.g., in infected people, are expected to control viral replication and prevent wide-spread infection in the CNS, and this could be consistent with the lack of changes in the CNS of A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza–infected cotton rats.

In conclusion, neither the AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine nor its individual components (the vaccine antigen or AS03) were able to induce inflammation or damage in the CNS or disruption of the BBB in the cotton rat model. However, these results do not exclude that narcolepsy development in the post-vaccination period in humans does not involve any kind of inflammatory response. Clearly, there are biological differences between cotton rats and humans, and the rarity of these particular narcolepsy signals in humans should also be taken into consideration, i.e., the present studies were not powered to detect such rare events. Genetic factors such as the presence of the HLA-DQB10602 allele8,10 in most of the affected humans also contribute to the development of this pathology, potentially suggesting a role for CD4+ T cells.

Materials and methods

Study designs and objectives

The four studies were conducted at Sigmovir Biosystems, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA, in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and the facility's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee's approved study protocol. Study objectives were the evaluation of the potential CNS inflammation/damage (Studies 1 and 2) and disruption of the BBB integrity (Studies 3 and 4) following administration of the test articles (non-adjuvanted vaccine and AS03 alone in Studies 1 and 3, and AS03-adjuvanted vaccine in Studies 2 and 4) or placebo (saline) used in all studies (Table 1). In each study, 1-month-old female cotton rats were randomly allocated to treatment groups (N = 24 per group). They were either primed intranasally with wild-type A(H1N1)pdm09 virus at a dose of 4.0 log10 TCID50, 3 weeks before vaccination, or left naïve, and subsequently received 2 or 3 intramuscular injections, respectively, at 2-week intervals. Depending on the study objective, subgroups of 6 animals were sacrificed at 6, 24, 48 or 72 h after the last dosing (Days 35, 36, 37 and 38; Studies 3 and 4), or at 3 d or 1, 2 or 3 months after the last dosing (Days 38, 65, 95, and 125, respectively; Studies 1 and 2). For logistical reasons, Study 1 was conducted in 2 phases (1A and 1B; N = 12/group each phase), with different days of sacrifice (Days 38 and 66 in Study-1A, and Days 95 and 125 in Study 1B).

Control and test articles and treatments

Virus priming

Wild-type A(H1N1)pdm09 (A/California/7/2009) virus stock at a concentration of approximately 7.0 log10 TCID50 per ml was stored at −80 °C. Immediately prior to use (or within an hour of use), the virus stock was thawed and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline to achieve a predetermined optimal priming dose of 4.0 log10 TCID50 per animal (100 μl, intra-nasal/intra-tracheal) in the appropriate experimental groups (D-F in Studies 1 and 3, and C and D in Studies 2 and 4; see Table 1).

Non-adjuvanted H1N1 vaccine

The non-adjuvanted, monovalent, inactivated, split virion A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine was manufactured by GSK, Dresden, Germany, from the reassortant virus NYMC X-179A, and provided in vials containing 3.1 ml each. Since the vaccine lot DFLSA014A used in this study, which was a clinical development lot with a composition similar to that of the commercial lots used in vaccination campaigns in Europe, was expired, and because commercial lots were no longer in production, subsequent measurements of the HA antigen content were performed in October 2014 (in triplicate), using the standard single radial immunodiffusion method. The analysis demonstrated that the mean actual HA antigen content was 12.8 μg/ml, thus fulfilling the commercial specifications (i.e., not less than of 80% of the minimum value at release of 15 μg HA/ml).

AS03

AS03A (elsewhere in this article referred to as AS03) is an oil-in-water emulsion containing 11.86 mg α-tocopherol, 10.69 mg squalene and 4.86 mg polysorbate-80 per adult-human dose.2,30,36 The test article was provided in vials containing 3.1 ml each (GSK, Rixensart, Belgium; Lot AA03A209C).

Control

A saline solution (0.9% NaCl) was used.

Formulation of AS03-adjuvanted H1N1 vaccine

The final formulation was prepared within 1 h before injection by mixing (1:1 v/v) the vaccine antigen suspension and the AS03 emulsion.

Treatments

Test articles or placebo were administered by intramuscular injection (the clinical administration route) in the left upper hind leg (M. quadriceps) of non-sedated animals. The test articles were each administered in an amount that constituted an overdose compared to their respective equivalent human pediatric and adult dosages, on a body-weight basis.

For the non-adjuvanted vaccine group, the injection volume was 50 μl of the vaccine antigen suspension, whereas for the adjuvanted vaccine group, the injection volume was 100 μl of the formulated AS03-adjuvanted vaccine. In both groups, the injected doses were formulated to target doses of 0.75 µg HA per injection, equivalent to 1/5th of the adult-human dose or 2/5th of the pediatric dose (where a 0.5-ml adult-human dose of Pandemrix™ contained 3.75 µg HA and AS03A, and a 0.25-ml pediatric dose [for children aged 6 months to 9 y inclusive] contained 1.9 μg HA and half a dose of AS03A [designated AS03B]2,3).

The animals injected with AS03 alone received a dose-volume of 100 μl per injection, equivalent to 2/5th of the adult-human dosage of 0.25 ml, or 4/5th of the pediatric dosage.

Animal husbandry

Inbred female cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) were obtained from the Sigmovir Biosystems, Inc. animal colony (N = 144, N = 96, N = 144, and N = 96 in Studies 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively). On Day 0, animals were 4–5 weeks of age and weighed on average 74, 77, 58, and 53 g in Studies 1A, 1B, 2, and 4, respectively (in Study 3, body weights were not measured at Day 0). Animals were housed in clear polycarbonate cages (3 per cage) in rooms with air temperature and relative humidity maintained between 20–24 °C and 25–75%, respectively. They were provided with a standard rodent diet (Harlan #7004) and tap water ad libitum.

Clinical observations

Animals were observed twice or once daily during weekdays and weekends, respectively. Mortality, morbidity and clinical signs were recorded.

Body weights

Body weights were recorded in Studies 1 and 2 at the time-points indicated (Table 1). In each group, the respective average weights on Day 0 (in Studies 1A and 1B) or on Day -3 (in Study2) were used as reference to measure percentages weight gain on subsequent time-points.

Blood sampling

In Studies 2 and 4, blood for HI antibody assays was drawn by cardiac puncture at 3 d or 1, 2 or 3 months post last dose in Study 2, and at 3 d post last dose in Study 4. In Studies 3 and 4, blood for hematology and serum cytokines analyses was drawn retro-orbitally at Day 35 (6 h after last vaccination), and at Days 36, 37 and 38.

Hematology (Studies 3 and 4)

Hematology was assessed by VRL, Rockville, MD, USA. Blood samples were visually inspected and analyzed within 24 h after collection using a Siemens ADVIA 120 Hematology Analyzer. White blood cell (WBC) counts (neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils and basophils) were determined.

Serum cytokines (Studies 3 and 4)

Serum levels of IL-6, IFN-γ and TNF-α were measured by ELISA using R&D Systems Duo Sets DY561, DY565, and DY1011, respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions. In both studies, serum samples from a separate group of unmanipulated cotton rats, with or without added fixed amounts of cytokines ([IL-6] = 18 ng/mL; [TNF-α] = 32 ng/mL; [IFN-γ] = 16 ng/mL) were included as positive and negative control, respectively. All samples were analyzed in 1:5 dilutions, in triplicate.

HI antibody assay (Studies 2 and 4)

HI antibody responses elicited by the adjuvanted vaccine were evaluated by HI assay based on a previously described method,37 at the time-points indicated in Table 1. Briefly, serum samples were treated with receptor-destroying enzyme, then with 5% chicken erythrocyte suspension. Two-fold serial dilutions (1/20 starting dilution) were made in 96-well V-bottom assay plates (PS-microplate, Greiner Bio-One). Whole inactivated A(H1N1)pdm09 reassortant vaccine virus diluted to a predetermined optimal number of hemagglutination units (8 HA) was added to each serum sample. Assay plates were incubated (room temperature, 45 minutes), then 0.5% chicken erythrocyte suspension was added to each well and the plates were incubated (room temperature, 45 minutes) and read. The assay's limit of detection was set at 10.

CSF hypocretin (Studies 1 and 2)

CSF samples (∼20 μl) were collected from the cisterna magna at sacrifice in Studies 1 and 2. Hypocretin levels were measured at Stanford School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA, using a radioimmunoassay as described previously.38

Brain histopathology (Studies 1–4)

Animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation at the time-points indicated in Table 1. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E)-stained slides of the brains were prepared by HistoServ (Germantown, MD, USA). Immunohistochemical staining was performed for Iba1, CD68, albumin and hypocretin by GSK, Rixensart, Belgium. Histopathological examinations were performed by Dr Thomas March (Albuquerque, NM, USA). Numbers of hypothalamic hypocretin-positive neuronal bodies were scored on a 3-grade system (1: <50 hypocretin-positive cells; 2: 50–100 hypocretin-positive cells; and 3: >100 hypocretin-positive cells, usually more abundant in the rostral section). The extent and intensity of hypocretin-positive staining of axonal and dendritic projections were scored subjectively on a 4-grade system (1: faint staining, less widely distributed; 4: strong, widely dispersed positive staining). Histopathology methods are described in full in the online supplement (Supp. Methods).

Statistics

Group reciprocal geometric mean titers (GMTs) of HI antibodies were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using GraphPad Prism 6. CSF hypocretin levels were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the log10 values. Estimates of the geometric mean ratios between groups and their 95% CI were obtained by back-transformation on the log10 values. Adjustment for multiplicity was performed using Tukey's method. Hematology and weight change data of the treatment groups were compared to those of the naïve control group by time-point by t-test. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Trademark

Pandemrix is a trade mark of the GSK group of companies.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

KY, JCGB, MB, CP and ED were involved in the conception and design of the studies. KY, JCGB, MB and TM acquired the data. All authors analyzed and interpreted the results. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data and approved the manuscript before it was submitted by the corresponding author.

All authors have declared that the following interests are relevant to the submitted work. CP, CPM, RvdM and ED are, or were at the time of the study, employees of the GSK group of companies. CPM, RvdM and ED own GSK stocks. CPM and RvdM are listed as an inventor on patents owned by GSK. MB, KY and JCGB are employees of Sigmovir Biosystems Inc., a contract research organization that was contracted by Glaxo-SmithKline in the context of this study. TM reports personal fees from Sigmovir Biosystems, Inc., during the conduct of the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following coworkers from GSK: Nadia Ouaked for performing pilot studies with wild-type A/California/7/2009 in cotton rats, Marie-Hélène Joly for performing viral titration and HI assays, Frédéric Renaud for performing the statistical analyses, Michel Bisteau and Luc Scholliers for immunohistochemistry staining, and Arnaud Didierlaurent and Marcelle van Mechelen for helpful scientific discussions. They also thank Ling Lin and Emmanuel Mignot (Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, USA) for CSF hypocretin measurements and analyses, Pratibha Vohra (HistoServ, Germantown, MD, USA) for histological slides preparation, Arlene Leon (VRL, Rockville, MD, USA) for hematology assessments, Xiyan Xu (Influenza Division, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) for supplying the A/California/7/2009 virus used in the pilot study and in the studies reported herein, and Andrea Zeiss, Kati Zierenberg and Elisabeth Neumeier (GSK) for single radial immunodiffusion measurements of the vaccine's antigen content. Finally, they thank Ellen Oe (XPePharma on behalf of GSK) for providing scientific writing services in the manuscript's development and Ulrike Krause (GSK) for publication management.

Funding

This study was sponsored and funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, which was involved in all stages of the study conduct and analysis. The costs associated with the development and publishing of the manuscript, including scientific writing assistance, were also funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA.

References

- [1].European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Narcolepsy in association with pandemic influenza vaccination - a multi-country European epidemiological investigation). Stockholm; 2012; 159 p. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC) Pandemrix suspension and emulsion for emulsion for injection: Summary of product characteristics. Last updated on the eMC on 01/08/2013. [Google Scholar]

- [3].European Medicines Agency http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/000832/human_med_000965.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124 European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) for Pandemrix, EMA/691037/2013. Annex I: Summary of product characteristics. 27-10-2015. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mereckiene J, Cotter S, Weber JT, Nicoll A, D'Ancona F, Lopalco PL, Johansen K, Wasley AM, Jorgensen P, Lévy-Bruhl D, et al.. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination policies and coverage in Europe. Euro Surveill 2012; 17:pii: 20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dauvilliers Y, Montplaisir J, Cochen V, Desautels A, Einen M, Lin L, Kawashima M, Bayard S, Monaca C, Tiberge M, et al.. Post-H1N1 narcolepsy-cataplexy. Sleep 2010; 33:1428-30; PMID:21102981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Heier MS, Gautvik KM, Wannag E, Bronder KH, Midtlyng E, Kamaleri Y, Storsaeter J. Incidence of narcolepsy in Norwegian children and adolescents after vaccination against H1N1 influenza A. Sleep Med 2013; 14:867-71; PMID:23773727; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Han F, Lin L, Warby SC, Faraco J, Li J, Dong SX, An P, Zhao L, Wang LH, Li QY, et al.. Narcolepsy onset is seasonal and increased following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in China. Ann Neurol 2011; 70:410-7; PMID:21866560; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ana.22587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kornum B, Faraco J, Mignot E. Narcolepsy with hypocretin/orexin deficiency, infections and autoimmunity of the brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2011; 21:897-903; PMID:21963829; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.conb.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Blouin AM, Thannickal TC, Worley PF, Baraban JM, Reti IM, Siegel JM. Narp immunostaining of human hypocretin (orexin) neurons: loss in narcolepsy. Neurology 2005; 65:1189-92; PMID:16135770; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1212/01.wnl.0000175219.01544.c8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hallmayer J, Faraco J, Lin L, Hesselson S, Winkelmann J, Kawashima M, Mayer G, Plazzi G, Nevsimalova S, Bourgin P, et al.. Narcolepsy is strongly associated with the T-cell receptor alpha locus. Nat Genet 2009; 41:708-11; PMID:19412176; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng.372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med 2013; 19:1584-96; PMID:24309662; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kivisäkk P, Mahad DJ, Callahan MK, Trebst C, Tucky B, Wei T, Wu L, Baekkevold ES, Lassmann H, Staugaitis SM, et al.. Human cerebrospinal fluid central memory CD4+ T cells: Evidence for trafficking through choroid plexus and meninges via P-selectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100:8389-94; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1433000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, Derecki NC, Castle D, Mandell JW, Lee KS, et al.. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 2015; 523:337-41; PMID:26030524; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].van der Most R, Van Mechelen M, Destexhe E, Wettendorff M, Hanon E. Narcolepsy and A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination: Shaping the research on the observed signal. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:572-6; PMID:24342916; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.27412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang S, Lin L, Kaur S, Thankachan S, Blanco-Centurion C, Yanagisawa M, Mignot E, Shiromani PJ. The development of hypocretin (orexin) deficiency in hypocretin/ataxin-3 transgenic rats. Neuroscience 2007; 148:34-43; PMID:17618058; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gerashchenko D, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Lin L, Xu M, Hallett L, Nishino S, Mignot E, Shiromani PJ. Relationship between CSF hypocretin levels and hypocretin neuronal loss. Exp Neurol 2003; 184:1010-6; PMID:14769395; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00388-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gerashchenko D, Blanco-Centurion C, Greco MA, Shiromani PJ. Effects of lateral hypothalamic lesion with the neurotoxin hypocretin-2-saporin on sleep in Long-Evans rats. Neuroscience 2003; 116:223-35; PMID:12535955; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00575-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bouvier NM, Lowen AC. Animal models for influenza virus pathogenesis and transmission. Viruses 2010; 2:1530-63; PMID:21442033; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/v20801530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Eichelberger MC. The cotton rat as a model to study influenza pathogenesis and immunity. Viral Immunol 2007; 20:243-9; PMID:17603841; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/vim.2007.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Boukhvalova MS, Prince GA, Blanco JC. The cotton rat model of respiratory viral infections. Biologicals 2009; 37:152-9; PMID:19394861; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Blanco JC, Pletneva LM, Wan H, Araya Y, Angel M, Oue RO, Sutton TC, Perez DR. Receptor characterization and susceptibility of cotton rats to avian and 2009 pandemic influenza virus strains. J Virol 2013; 87:2036-45; PMID:23192875; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.00638-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Niewiesk S, Prince G. Diversifying animal models: the use of hispid cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) in infectious diseases. Lab Anim 2002; 36:357-72; PMID:12396279; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1258/002367702320389026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dheen ST, Kaur C, Ling EA. Microglial activation and its implications in the brain diseases. Curr Med Chem 2007; 14:1189-97; PMID:17504139; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/092986707780597961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McMenamin PG. Distribution and phenotype of dendritic cells and resident tissue macrophages in the dura mater, leptomeninges, and choroid plexus of the rat brain as demonstrated in wholemount preparations. J Comp Neurol 1999; 405:553-62; PMID:10098945; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990322)405:4%;3c553::AID-CNE8%;3e3.0.CO;2-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ottolini MG, Blanco JC, Eichelberger MC, Porter DD, Pletneva L, Richardson JY, Prince GA. The cotton rat provides a useful small-animal model for the study of influenza virus pathogenesis. J Gen Virol 2005; 86:2823-30; PMID:16186238; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1099/vir.0.81145-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Segal L, Wouters S, Morelle D, Gautier G, Le Gal J, Martin T, Kuper F, Destexhe E, Didierlaurent AM, Garçon N. Non-clinical safety and biodistribution of AS03-adjuvanted inactivated pandemic influenza vaccines. J Appl Toxicol 2015; 35:1564-76; PMID:25727696; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jat.3130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tsunematsu T, Tabuchi S, Tanaka KF, Boyden ES, Tominaga M, Yamanaka A. Long-lasting silencing of orexin/hypocretin neurons using archaerhodopsin induces slow-wave sleep in mice. Behav Brain Res 2013; 255:64-74; PMID:23707248; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, et al.. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell 1999; 98:437-51; PMID:10481909; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81973-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, et al.. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron 2001; 30:345-54; PMID:11394998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00293-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Morel S, Didierlaurent A, Bourguignon P, Delhaye S, Baras B, Jacob V, Planty C, Elouahabi A, Harvengt P, Carlsen H, et al.. Adjuvant System AS03 containing α-tocopherol modulates innate immune response and leads to improved adaptive immunity. Vaccine 2011; 29:2461-73; PMID:21256188; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Destexhe E, Prinsen MK, van Schöll I, Kuper CF, Garçon N, Veenstra S, Segal L. Evaluation of C-reactive protein as an inflammatory biomarker in rabbits for vaccine nonclinical safety studies. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2013; 68:367-73; PMID:23624216; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vascn.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Paine NJ, Ring C, Bosch JA, Drayson MT, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJ. The time course of the inflammatory response to the Salmonella typhi vaccination. Brain Behav Immun 2013; 30:73-9; PMID:23333431; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Burny W, Callegaro A, Fissette L, Hervé C, van den Berg R, Esen M, Haelterman E, Horsmans Y, Jilg W, Kremsner P et al.. Associations between reactogenicity symptoms and parameters of the early immune response to adjuvanted vaccines in humans. The Modes of Action of Vaccine Adjuvants (S1) 2014; Workshop 4: Adjuvant Profiling [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tesoriero C, Codita A, Zhang MD, Cherninsky A, Karlsson H, Grassi-Zucconi G, Bertini G, Harkany T, Ljungberg K, Liljeström P, et al.. H1N1 influenza virus induces narcolepsy-like sleep disruption and targets sleep-wake regulatory neurons in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113:E368-E377; PMID:26668381; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1521463112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wei CJ, Boyington JC, Dai K, Houser KV, Pearce MB, Kong WP, Yang ZY, Tumpey TM, Nabel GJ. Cross-neutralization of 1918 and 2009 influenza viruses: role of glycans in viral evolution and vaccine design. Sci Transl Med 2010; 2:24ra21; PMID:20375007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Garçon N, Vaughn DW, Didierlaurent AM. Development and evaluation of AS03, an Adjuvant System containing α-tocopherol and squalene in an oil-in-water emulsion. Expert Rev Vaccines 2012; 11:349-66; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1586/erv.11.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mallett CP, Beaulieu E, Joly MH, Baras B, Lu X, Liu F, Levine MZ, Katz JM, Innis BL, Giannini SL. AS03-adjuvanted H7N1 detergent-split virion vaccine is highly immunogenic in unprimed mice and induces cross-reactive antibodies to emerged H7N9 and additional H7 subtypes. Vaccine 2015; 33:3784-7; PMID:26100923; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Aran A, Shors I, Lin L, Mignot E, Schimmel MS. CSF levels of hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) peak during early infancy in humans. Sleep 2012; 35:187-91; PMID:22294808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.