Abstract

Objective

To explore the acceptability of currently available treatments and services for individuals who self-report hoarding behaviors.

Method

Between 10/2013 and 8/2014, participants were invited to complete an online survey that provided them descriptions of eleven treatments and services for hoarding behaviors and asked them to evaluate their acceptability using quantitative (0 [not at all acceptable] -10 [completely acceptable]) Likert scale ratings. The a priori definition of acceptability for a given resource was an average Likert scale score of six or greater. Two well-validated self-report measures assessed hoarding symptom severity: the Saving Inventory-Revised and the Clutter Image Rating Scale.

Results

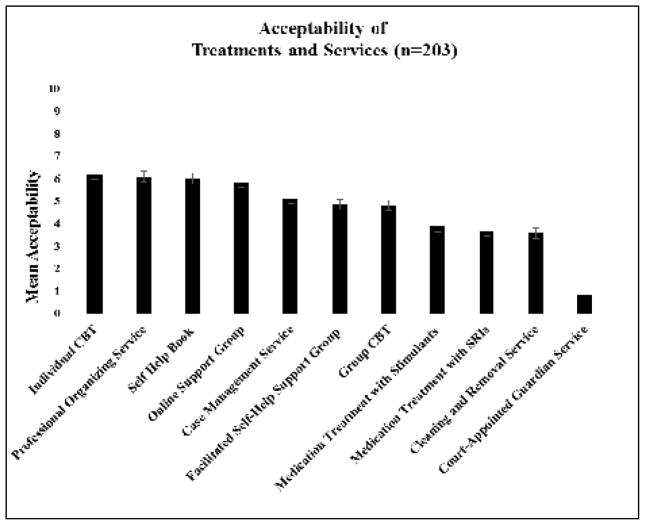

Two hundred and seventy two participants who self-reported having hoarding behaviors completed the questionnaire. Analyses focused on the 73% of responders (n=203) who reported clinically significant hoarding behaviors (i.e., Saving Inventory-Revised scores of ≥40). The three most acceptable treatments were individual cognitive behavioral therapy (6.2 ±3.1 on the Likert scale), professional organizing service (6.1 ±3.2), and use of a self-help book (6.0 ±3.0).

Conclusion

In this sample of individuals with self-reported clinically significant hoarding behaviors (n=203), only 3 out of 11 treatments and services for hoarding were deemed acceptable using an a priori score. While needing replication, these findings indicate the need to design more acceptable treatments and services to engage clients and maximize treatment outcomes for hoarding disorder.

Keywords: Hoarding Disorder, Treatment Acceptability, SRI, Stimulant, CBT

Introduction

Hoarding disorder, characterized by difficulty parting with a large volume of possessions that results in distress and impaired functioning, is a new diagnostic entity in DSM-5.1 Despite its prevalence (2–6%)2–4 and impact on public health,5–7 under-utilization of mental health resources by consumers remains a challenge.8–11 Consistent with the recent emphasis on patient-centered care, 12, 13 we hypothesized one potential reason that treatments and services for hoarding disorder were under-utilized was that clients did not find these treatments acceptable. Identifying what types of treatments are acceptable can help inform community treatment programs for individuals with hoarding disorder as well as guide future treatment development.

The term “acceptability” originates from the field of implementation science and has been defined as follows: “Acceptability is the perception among implementation stakeholders that a given treatment, service, practice or innovation is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory.”14 Proctor et al (2011) describe that, unlike the larger construct of service satisfaction (typically measured through consumer surveys referencing the general service experience), acceptability is more specific, referencing a particular set of treatments based on consumer’s knowledge of the dimensions of treatment (e.g. content, complexity, or comfort). Lack of acceptability has been previously described as an obstacle to transferring treatments from research to practice.14, 15 Furthermore, it has been suggested that treatment acceptability may underlie treatment choice.16 Assessing acceptability and the factors that influence acceptability may add insights to research examining mental health utilization by individuals with hoarding behaviors.17, 18

One prior online study aimed at understanding the economic and social burden in individuals who self-identified as having hoarding behaviors (n=864) also examined general attitudes toward mental health treatment in this sample.17 Of the participants who reported attitudes toward mental health treatment (n=853), 720 (84.4%) reported that they would (probably or definitely) go for treatment for their problems with hoarding behaviors.17 However, to date, no studies have queried what types of available treatments and services are acceptable to individuals with clinically significant hoarding behaviors.

To close the gap and explore this important issue for the first time in a community sample, we used a method of convenience (e.g. an online survey) to assess the acceptability of eleven currently available treatments and services for individuals who self-report suffering from clinically significant hoarding behaviors.

Method

Subjects were recruited between October 2013 and August 2014 by online advertisements (e.g. iocdf.org, meetup.com, craigslist.org). Advertisements were designed to recruit eligible adults (over age 18) who self-identified as having problems with different types of potential hoarding behaviors (i.e., “Do you have trouble with clutter, excessive collecting, or hoarding?”). The self-report survey was administered using surveymonkey.com. After study completion, participants were eligible to enter a lottery (unlinked to participant’s survey answers) with a one in one-hundred chance to win a $100 gift card to Amazon.com. The Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute approved the study.

Survey Instrument

The survey was developed by the authors and designed to be completed in 30 minutes. It included five sections: 1) demographics, 2) current hoarding symptoms, 3) the acceptability of treatments and services, 4) personal experiences with treatments and services for hoarding behaviors and 5) current mood. Each section is described below.

Demographics

Participants were queried about sex, age, racial and ethnic background, marital status, income, education, employment status, geographic location, and health insurance.

Current Hoarding Symptoms

Two self-report measures assessed hoarding symptom severity: the Saving Inventory-Revised (SI-R)19 and the Clutter Image Rating Scale (CIR).20

The SI-R is a 23-item self-report measure of hoarding disorder behaviors in three subscales: clutter (9 items), difficulty discarding (7 items), and acquisition (7 items). Each item is rated from 0 to 4, with higher numbers indicating greater symptom severity. A total score of 40 or more indicates clinically significant hoarding behaviors.19 Internal reliabilities for the SI-R (subscales and full scale) in this study ranged from good to excellent (α = 0.83 to α = 0.93).21

The CIR is a 3-item picture scale assessing level of clutter with high internal consistency and test-retest reliability.20 Individuals are asked to match their level of clutter to one of nine pictures numbered from 1 to 9, with higher number indicating greater clutter. Scores for three representative rooms (kitchen, bedroom, living room) are averaged. Internal consistency for these three rooms was good (α = 0.84). Individuals with hoarding behaviors can reliably rate the level of their clutter with the CIR; strong correlations have been reported between participant self-report and experimenter ratings in the home (r = .74).20

Finally, in addition to the self-report measures described above, participants were also asked the following question: “Are you worried you may be at risk for eviction?”

Acceptability of Treatments and Services

Acceptability was assessed using an analogue Likert scale from 0 (not at all acceptable) to 10 (completely acceptable) for eleven treatments and services for hoarding disorder (see Table 2). The a priori cutoff for a given resource being “acceptable” was an average Likert scale score ≥ 6; this score was chosen because it reflects more than a neutral stance (putatively a “5”) to the given resource. The eleven chosen (see below “Selection of Treatments and Services” for methods) spanned different types of resources including: self-help (i.e., self-help book, facilitated self-help support group, online support group), psychotherapy (i.e., individual cognitive behavioral therapy, group cognitive behavioral therapy), medications (serotonin reuptake inhibitor, stimulants), and community services (cleaning and removal service, professional organizing service, case management service, court-appointed guardian). Descriptions of each treatment or service were provided in English using both audio and written presentations to enhance ecological validity.13 Each description included information about risks, benefits, cost, and time commitment (see Appendix 1 for full descriptions). For each treatment and service, participants were asked in open-ended questions (see Appendix 2 for example screenshot) which aspects they found acceptable and unacceptable, and what they anticipated might be barriers to seeking out that particular intervention.

Table 2.

Qualitative Data on Acceptable and Unacceptable Aspects of Treatments and Services for Individuals with Hoarding Behaviors

| Treatments and Services | Domains Acceptable Aspectsa | Quotes | Domains Unacceptable Aspectsb | Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual CBT | Personalized Care | “Having one person who knows me…might actually work.” | ||

| Being Held Accountable | “[I would be] forced to address my issues and with an expert” | None | N/A | |

| Personal Organizing Service | Belief Treatment Works | “This is the most useful option.” | ||

| Belief Treatment Works | “they would help with something that is virtually impossible for me” | None | N/A | |

| Self-Help Book | Privacy | “It’s good because no one has to come and see the mess.” | Not Motivated to Change | “No motivation to actually do it.” |

| Control over the Process | “I control when and how I access it.” | Doubting Treatment Works | “Would feel like I wasn’t doing something productive by reading” | |

| Online Support Group | Privacy | “Easier to admit anonymously.” | Fear of Being Judged | “If the people are judgmental, harsh or not compassionate.” |

| Easy to do | “Easier to attend with a busy schedule.” | Doubting Treatment Works | “[I] have a sort of hopelessness that it will make any difference” | |

| Case Management Service | Personalized Care | “It sounds like it may provide highly individualized help.” | None | N/A |

| Facilitated Self-Help Support Group | Social Support | “[This treatment] would give me acceptance from others.” | Fear of Being Judged | “It’s perceived as something normal people can control. Admitting to strangers is probably harmless but still difficult.” |

| Group CBT | Social Support | “Mutual encouragement and support” | None | N/A |

| Medication Treatment with Stimulants | Belief Treatment Works | “I believe treating my attention difficulties would be very helpful to me.” | Anticipated Distress/Harm | |

| Anticipated Distress/Harm | “I…have some worry about long term effects on the brain. | |||

| Medication Treatment with SRIs | Belief Treatment Works | “Recognizes a deeper problem that can’t be “talked” away? | Doubting Treatment Works | “Would rather get to the root of the issue--I think the hoarding is rooted in anxiety rather than medical problems” |

| Cleaning and Removal Service | In-Home Help | “I would love to have help cleaning, decluttering and organizing my home.” | Anticipated Distress/Harm | “Having an entire team enter my home sounds very stressful” |

| Belief Treatment Works | “My place would actually get clean” | Lack of Control over the Process | “Using their criteria to discard things instead of mine.” | |

| Court-Appointed Guardian Service | None | N/A | Lack of Control over the Process | “I do not want anyone making decisions for me.” |

Range of number of participants who wrote responses for acceptable aspects of Treatments and Services n=70–160

Range of number of participants who wrote responses for unacceptable aspects of Treatments and Services n=75–150

Abbreviations: CBT=cognitive behavioral therapy, SRI=serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Personal Experiences with Treatments and Services

Using a checklist format, participants were asked which of the 11 treatments and services, if any, they had ever tried in the past (regardless of whether the treatments were specifically for hoarding or other comorbid conditions), and which, if any, they would be interested in trying in the future.

Current Mood

Mood was assessed using the 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), a self-report measures of depression, anxiety, and stress.22 Ratings of the relevancy of each of the three negative affective states over the past week were reported on four point Likert scale (0–3). A score of 0 indicated that the item “did not apply” and a score of 3 meant that the participant considered the question to apply “very much, or most of the time.” This scale has been used in prior studies of hoarding disorder9 and has high concurrent validity and reliability.23 Internal reliabilities for the DASS-21 (subscales and full scale) in this study ranged from good to excellent (α = 0.80 to α = 0.93).21

Selection of Services and Treatments

To canvas potential treatments and services for inclusion in the acceptability survey, a search was conducted on August 1st, 2013 through the academic databases PubMed and Google Scholar using the search term ‘hoarding’ combined with a set of terms related to treatments and services, including therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), psychotherapy, medication, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, stimulants, psychopharmacology, self-help, community services, and treatment study. This search yielded 305 studies. We then applied the following inclusion criteria: a) hoarding was the primary condition being studied; b) validated measures of hoarding were included; c) the study was an open or randomized controlled trial of an intervention. Thirteen studies8, 9, 11, 24–33 met these criteria (only 3 of which were a randomized controlled trial 11, 25, 28). To enhance generalizability, we also included treatments and services that were commonly offered to individuals with hoarding behaviors by a government or non-profit community agencies or organizations (i.e. adult protective services, eviction intervention services, housing court). The only community services excluded were hoarding task forces, in which key elements of the intervention are different from city to city thus difficult to capture in a succinct description needed for survey use (e.g., variability of hoarding task force members, meeting intervals, and resources offered).

Once the descriptions were prepared, the co-authors next sought independent feedback on the compiled list of treatments and services and the content of individual descriptions. Consideration was given to soliciting feedback from all hoarding researchers and members of the International OCD Foundation (IOCDF) hoarding interest group; however, given the pilot nature of the study and the need for the descriptions to match each other as nearly as possible in sentence structure, word count, and grade level while ensuring readability, the decision was made to assemble a focused group. To employ this targeted approach, RF identified 4 hoarding researchers and active members of the IOCDF hoarding interest group that represented fields of psychiatry, psychology, social work, and community services) who were emailed an invitation to provide feedback on the overall list and content of each description. After incorporating feedback from this independent panel, the descriptions’ readability was vetted by SRP using a readability formula commonly used to assess health education materials, the Simplified Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), 34, 35 and then the authors [CIR, RF, and HBS] reviewed and approved the final content.

Quantitative Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package Social Sciences, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) on participants who had clinically significant hoarding behaviors (n=203). Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographics, experience with any treatment and services status (non-experienced vs experience with at least one service), as well as ratings of acceptability. Using collapsed dichotomous variables for acceptability (acceptable [6–10] versus not acceptable [0–5]), gender (female vs male), income (low [<$25,000] vs other), Chi-square analyses and Pearson correlations were used to examine exploratory associations between demographic and treatment variables and acceptability ratings. Alpha = .05 was used as the criteria for significance. Given the exploratory nature of this study, corrections for multiple comparisons were not made, thus Type I error cannot be ruled out.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative data were abstracted using an inductive process previously described.36 Two coders (AL and JZ) each developed a preliminary list of domains by independently reviewing the qualitative reasons given for acceptability, unacceptability, and barriers to care. The coders then met and iteratively modified these domains by comparing data and the derived domains and discussing to consensus until core domains emerged. For acceptable and unacceptable aspects and barriers to care, we present domains that at least 10% of the sample36 reported.

Results

Sample

Two hundred and seventy two individuals completed the online survey. The analyses focused on only those individuals who self-reported clinically significant hoarding behaviors (n=203, 73%) on the Saving Inventory Revised (SI-R ≥ 40) to assess treatment acceptability in those who could benefit from treatment. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of participants who had clinically significant hoarding behaviors (n=203). Most of the participant sample were middle-aged (48 years old [SD = 18]), Caucasian (76%) women (80%), who were not married nor living with a partner (54%). Approximately 30% of the sample had an income of < $25,000. Individuals had some higher levels of education (56% completed college and 27% also had a graduate or professional degree) and low rate of current unemployment (13%). Participants reported moderate levels of clutter: mean CIR score was 3.6 (SD = 1.4) out of a total 9 (maximal clutter). Participants had moderate levels of depression (DASS-21 score was 9 [SD =6]), mild levels of anxiety (5 [SD = 4]), and mild levels of stress (9 [SD = 5]). Only 18% endorsed concerns about being evicted. Those who did reported higher levels of clutter using both the CIR mean score 4.5 (SD = 1.6) (F =35.95, p <.001) and the SI-R clutter subscale mean score 25 (SD = 6.5) (F = 14.48, p <.001), but not significantly higher levels of other hoarding behaviors, using the other 2 SI-R subscales.

Table 1.

Demographic Variables for Sample (N=203*)

| Patient Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 33 (16) |

| Female | 162 (80) |

| Other | 8 (4) |

| Age in Years, Mean (SD) | 47.9 (18) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 12 (6) |

| Non-Hispanic | 172 (85) |

| Elected not to answer | 19 (9) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 155 (76) |

| African American | 12 (6) |

| Asian | 7 (3) |

| Other | 10 (5) |

| Elected not to answer | 19 (9) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single/Never Married | 69 (34) |

| Married/Living with Partner | 80 (39) |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 40 (20) |

| Elected not to answer | 14 (7) |

| Income per Year | |

| < $25,000 | 60 (30) |

| $25,000–$54,999 | 61 (30) |

| $55,000–$99,999 | 37 (18) |

| ≥$100,000 | 24 (12) |

| Elected not to answer | 21 (10) |

| Education | |

| Some High School (9th–12th Grade) | 3 (1) |

| High School Diploma | 11 (5) |

| Vocational Training (Beyond High School) | 7 (3) |

| Some College | 62 (31) |

| College Degree | 58 (29) |

| Graduate or Professional Degree | 54 (27) |

| Elected not to answer | 8 (4) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 86 (42) |

| Student/Homemaker/Retired | 47 (23) |

| Unemployed | 26 (13) |

| Disabled | 26 (13) |

| Elected not to answer | 18 (9) |

| Experience with Treatments and Services for Hoarding Behaviors | |

| Experience with one or more treatments or services | 141 (69) |

| Non-experienced | 62 (31) |

number of participants meeting criteria for clinically significant hoarding symptoms (SIR>40)

Values are shown as n (%) unless stated otherwise.

Treatment Acceptability

Among the 203 participants with clinically significant hoarding behaviors,, the three treatments or services that met criteria for “acceptable” treatments/services (average Likert scale score ≥ 6) were individual cognitive behavioral therapy (6.2 ± 3.1), professional organizing service (6.1 ± 3.2), and self-help book (6.0 ± 3.0) (Figure 1). Of the “not acceptable” treatments and services, the three lowest scores were serotonin reuptake inhibitors (3.7 ± 3.7), cleaning and removal services (3.6 ± 3.4), and court-appointed guardian (0.8 ± 1.9).

Figure 1.

Average Acceptability of Treatments and Services for Individuals with Hoarding Behaviors. Acceptability was assessed using an analogue Likert scale from 0 (not at all acceptable) to 10 (completely acceptable) for eleven treatments and services for hoarding disorder. Error bars indicate standard error. Abbreviations: CBT=cognitive behavioral therapy, SRI=serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Experiences with Treatments and Services

Approximately one-third of participants (31%) with clinically significant hoarding behaviors had never tried any of the treatments and services described (Table 1). Of the remaining two-thirds, the most commonly tried treatments and services were use of a self-help book (n=124), SRIs (n=59), and individual cognitive behavioral therapy (n=53). The three “acceptable” treatments and services (individual cognitive behavioral therapy, professional organizing service, self-help book) were also the resources participants were most interested in trying in the future, whether or not those participants had any prior treatment experience of any kind.

Exploratory Associations

We explored associations between demographic variables (gender and income), experience with treatments and services, and acceptability of treatments and services following Patel and Simpson (2010).36 Patterns of acceptability were similar between women and men except that a higher proportion of women found individual CBT (62% vs. 39%, χ2(1, N=199) = 5.81, p < .05), self-help books (56% vs. 33%, χ2(1, N=199) = 5.68, p<.05), and online support groups (54% vs. 30%, χ2(1, N=199) = 5.98, p<.05) acceptable. There were no significant difference between participants in the lowest income bracket and others (above versus below $25,000 annual household income) in the proportion rating each of these treatments and services acceptable. A significantly higher proportion of those who have experience with these treatments or services compared to those with no experience find group CBT (46% vs. 25%, χ2(1, N=203) =7.51, p<.01), stimulants (39% vs. 21%, χ2(1, N=203) = 6.78, p<.01), SRIs (35% vs. 14%, χ2(1, N=203) = 9.14, p<.005), and facilitated self-help group (45% vs. 22%, χ2(1, N=203) = 9.58, p<.005) acceptable.

Qualitative Data

A list of domains was generated by two of the authors [A.L. and J.Z.] independently reviewing the qualitative reasons given for acceptability, unacceptability, and barriers to care. Results for domains that reached the a priori threshold of a 10% endorsement rate across all of the participants36 are listed by category in Table 2 along with participant quotes. We then focused on the most salient factors for clinical care (i.e., the most acceptable aspects of the most acceptable treatments [Table 2, upper left] and the most unacceptable aspects of the most unacceptable treatments [Table 2, lower right]). Qualitative data suggest factors that made treatments and services most acceptable were personalized care (e.g., “It is one-on-one and specialized to my specific issues”), being held accountable (e.g., “[I would be] forced to address my issues”), and belief that the treatment/service works (e.g., “[this is] probably be the most effective method”). Factors that made treatments and services unacceptable were anticipated distress/harm (e.g., “It would be extremely emotionally painful;” “I…have some worry about long term effects on the brain”), doubts that that treatment works (e.g., “I would rather get to the root of the issue—I think that hoarding is rooted in anxiety rather than medical problems”), and lack of control over the process (e.g., “I would not want to give someone else that much control over my life”). As barriers to treatments and services, cost, time, and lack of access reached the 10% threshold as barriers across all eleven resources presented.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the acceptability of currently available treatments and services in individuals who self-report clinically significant hoarding behaviors. There were three main findings. First, only three treatments and services for hoarding behaviors (individual CBT, professional organizing, and self-help book) were rated acceptable using an a priori definition (≥6 on Likert scale; 10 being “completely acceptable”). Second, approximately one-third of participants, despite reporting clinically significant hoarding behaviors, had never tried any of the treatments and services described. Third, factors that made treatments and services more acceptable are personalization of care, being held accountable, and a belief that the treatment works. Taken together, these findings provide insights into the acceptability of treatments and services for hoarding behaviors from the client perspective and generate ideas for improvement of existing treatments and services to be tested in future studies.

Characteristics of our online sample are consistent with what is known about individuals with clinically significant hoarding behaviors from clinical and epidemiological studies. First, our sample was predominantly female, consistent with existing literature that females with hoarding disorder are more likely to seek (and enroll in clinical trials providing) treatment.37 Second, our sample had low income levels despite high levels of education; epidemiological studies have found that hoarding behaviors are associated with low income.2, 17, 18 Finally, that one third of our sample had no experience with any treatment is consistent with epidemiological studies examining treatment utilization in individuals with hoarding behaviors.17, 18

Only three treatments and services were deemed acceptable: individual CBT, professional organizing, and self-help book. However, these three just barely made the a priori cutoff of 6 on the Likert scale, suggesting there is an important gap between available resources and acceptability of those resources for clients with hoarding behaviors. For participants who had tried prior treatments, two of these (self-help book and individual CBT) were also among the most commonly tried treatments and services. Interestingly, self-help book and CBT are also those with the greatest level of evidence-based efficacy to date.37

Our data show medication treatments with SRIs were among the least acceptable, with only cleaning and removal services and court-appointed guardians having lower ratings. Our results are consistent with treatment preference studies in other disorders (e.g., major depression38 and posttraumatic stress disorder39–41) that report participants prefer treatment with psychotherapy over medications. Within the medication classes assessed in our survey, stimulants and SRIs were not meaningfully different in their acceptability. However, when we examine acceptability by experience with treatments and services, we found medications were more acceptable to those who had previously tried at least one treatment or service. A full medication history was not obtained, thus it is not possible to say whether those who had previously tried medications were more (or less) satisfied with this method of treatment. Future studies should incorporate medication history and assessment of efficacy.

That people with clinically significant hoarding behaviors had such low treatment acceptability ratings led us to review whether the same was true for patients with anxiety or other obsessive-compulsive related disorders. Here, we found a gap in the literature. One study in 2012 reviewed 15 randomized trials of self-help interventions for anxiety disorders (including generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and social phobia) and found none assessed acceptability in terms of any formalized measure of satisfaction.42 Acceptability of psychotherapies for OCD was evaluated in one large pragmatic effectiveness trial and one randomized controlled trial, but these focused on delivery formats for CBT interventions (low and high intensity respectively). 43, 44 Research on acceptability of mental health treatments is a burgeoning field, and further research is need to provide evidence-based, patient-centered care.12–14

Our qualitative findings suggest possible ways for government and local community agencies to maximize the impact of treatment programs for hoarding behaviors. First, given that personalization of care seemed to make treatments more acceptable, programs could consider offering a choice of multiple treatments and services and highlighting personalized care tenets (e.g. “one size does not fit all,” “let’s find the right treatment for you”). Second, given that patients seemed to want treatments that held them accountable, program developers may want to build in ways to increase accountability (e.g., helping the client create reasonable goals, making regular follow-up appointments to help the client monitor their own progress). Finally, given that believing that the treatment will work seems key, and that studies for pharmacotherapy for hoarding disorder exists (although more research is needed in larger studies with replication to increase this evidence base),8, 32, 33, 45, 46 psychoeducation to explain how a medication is thought to decrease hoarding behaviors may result in greater interest in pharmacological treatment initiation. Beyond psychoeducation, other ideas to proactively increase client’s hopes that treatments can work include increasing client exposure to former program participants who have decluttered their living space (e.g. flyers, newsletters, and panels highlighting success stories).

Several study limitations deserve consideration. First, given that the data come from an online survey, inherent sampling bias may exist, resulting in underrepresentation of individuals who have poor insight, low motivation to complete questionnaires, and those who do not have access to a computer or may be unfamiliar with computer use. Although our survey design prevented participants from advancing to the next assessment until all items were answered, for potentially sensitive demographic variables, we did not require an answer to advance, which may have resulted in data loss on specific items (e.g. income, employment). It is also possible that participants were not accurately self-reporting their hoarding behaviors. Replication with a subset of patients diagnosed in a face-to-face clinical interview and in-person evaluation of clutter is needed to test the hypotheses generated in this pilot trial. Second, we tested the acceptability based on the vetted descriptions of the treatments and services. These descriptions did not include information on relative cost or quantify the amount of time spent on behavioral interventions (e.g. practice parting with possessions), which may have impacted their acceptability. Constrained by minimizing patient burden, paragraphs may not have fully conveyed what the treatment might be like. It is also possible that a respondent may consider a treatment acceptable in general, but not something they would be interested in for themselves. Additionally, in this study, the treatment acceptability instrument itself is a limitation (an analogue Likert scale administered at a single time point), since it does not capture the complexity of patient preferences, which could change with the passage of time and other factors, including cost of treatments, access to care, and treatment experience like other validated scales aimed to assess these constructs. Finally, in a survey format, a detailed psychiatric medication and treatment history confirmed with a provider or pharmacy records was not possible (e.g. individual experiences of efficacy of a given treatment may impact acceptability).

In summary, studies suggest that treatment acceptability may underlie preferences for behavioral treatments, and perhaps, ultimately, treatment choice.16 Our data showing that the three acceptable treatments and services (i.e. individual CBT, professional organizing service, self-help book) were also the three resources individuals were most interested in trying in future, support this theory. Preferences have been shown to be an important indicator of treatment initiation, retention and possibly health outcomes.38, 47 Future studies should explore the question of acceptability in hoarding disorder treatment-seeking and treatment non-seeking samples and test how factors that influence acceptability of treatments/services can be utilized to maximize treatment outcomes for individuals and their communities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Only three treatments and services for hoarding behaviors (individual CBT, professional organizing, and self-help book) were rated acceptable using an a priori definition (≥6 on Likert scale; 10 being “completely acceptable”).

Approximately one-third of participants, despite reporting clinically meaningful hoarding behaviors, had never tried any of the treatments and services described.

Factors that made treatments and services more acceptable are personalization of care, being held accountable, and a belief that the treatment works.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the individuals who generously donated their time to participate in this research study. We thank Drs. Roberto Lewis-Fernandez, M.D., John Markowitz, M.D., and Frank Schneier, M.D. for helpful comments on the manuscript; they report no additional financial or other relationships relevant to the subject of this letter. All three are affiliated with New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Funding support:

This investigation was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health K23MH092434 (Dr. Rodriguez), K24MH09155 (Dr. Simpson), New York State Office of Mental Health Policy Scholar Program (Dr. Rodriguez), Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program (Dr. Rodriguez), Gray Matters Fellowship (Dr. Rodriguez), Graham Arader (Dr. Rodriguez), and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Drs. Essock, Rodriguez and Simpson).

Previous Presentation:

American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP), Phoenix, AZ December 9, 2014 (poster number T151)

Footnotes

Statements of Author Disclosure:

Role of Funding Sources:

Funding for this study was provided by NIMH Grants K23MH092423 and K24MH09155, New York State Office of Mental Health Policy Scholar Program, Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program, Gray Matters Fellowship, Mr. Graham Arader, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributors:

Authors Rodriguez, Levinson, Patel, Rottier, and Simpson designed the study with expert consultation from Frost, Shuer, and Essock. Descriptions of treatments and services were designed by authors Rodriguez, Levinson, and Patel to match each other as nearly as possible in sentence structure, wording and word count, grade level, and reading ease. Consumers and experts in the respective fields vetted the content of each description, and authors Rodriguez, Frost, and Simpson reviewed and approved the final overall content. Authors Rodriguez and Levinson wrote the IRB protocol. Authors Levinson, Rottier, and Patel conducted literature searches and provided summaries of previous research studies. Authors Levinson and Zwerling coded the qualitative data and conducted the statistical analysis. Author Rodriguez wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest:

Drs. Rodriguez, Patel, Essock, Frost, and Simpson, and Ms. Levinson, Rottier, Zwerling, and Mr. Shuer report no additional financial or other relationships relevant to the subject of this letter.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

4) REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Grados MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behav Res Ther. 2008 Jul;46(7):836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timpano KR, Exner C, Glaesmer H, et al. The epidemiology of the proposed DSM-5 hoarding disorder: exploration of the acquisition specifier, associated features, and distress. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011 Jun;72(6):780–786. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06380. quiz 878–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordsletten AE, Reichenberg A, Hatch SL, et al. Epidemiology of hoarding disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2013 Dec;203(6):445–452. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.130195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams L. Hoarding: a community health problem. Health Soc Care Community. 2000 Jul;8(4):229–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez C, Panero L, Tannen A. Personalized intervention for hoarders at risk of eviction. Psychiatr Serv. 2010 Feb;61(2):205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez CI, Herman D, Alcon J, et al. Prevalence of hoarding disorder in individuals at potential risk of eviction in New York City: a pilot study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012 Jan;200(1):91–94. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31823f678b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saxena S. Pharmacotherapy of compulsive hoarding. J Clin Psychol. 2011 May;67(5):477–484. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frost RO, Pekareva-Kochergina A, Maxner S. The effectiveness of a biblio-based support group for hoarding disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2011 Oct;49(10):628–634. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolin DF. Challenges and advances in treating hoarding. J Clin Psychol. 2011 May;67(5):451–455. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muroff J, Steketee G, Bratiotis C, Ross A. Group cognitive and behavioral therapy and bibliotherapy for hoarding: a pilot trial. Depress Anxiety. 2012 Jul;29(7):597–604. doi: 10.1002/da.21923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott SN. Acceptability of behavioral treatments: Review of variables that influence treatment selection. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1988;19:68–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter SL. Review of Recent Treatment Acceptability Research. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2007;42(3):301–306. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011 Mar;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis F. User acceptance of information technology: System characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies. 1993;38:475–487. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sidani S, Miranda J, Epstein DR, Bootzin RR, Cousins J, Moritz P. Relationships Between Personal Beliefs and Treatment Acceptability, and Preferences for Behavioral Treatments. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(10):823–829. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Gray KD, Fitch KE. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiatry Res. 2008 Aug 15;160(2):200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez CI, Simpson HB, Liu SM, Levinson A, Blanco C. Prevalence and Correlates of Difficulty Discarding: Results From a National Sample of the US Population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013 Sep;201(9):795–801. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a21471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frost RO, Steketee G, Grisham J. Measurement of compulsive hoarding: saving inventory-revised. Behav Res Ther. 2004 Oct;42(10):1163–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin DF, Renaud S. Development and Validation of the Clutter Image Rating. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2008;30(3):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):284. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovibond SHL, PF . Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation; Sydney: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayers CR, Wetherell JL, Golshan S, Saxena S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for geriatric compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2011 Oct;49(10):689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost RO, Ruby D, Shuer LJ. The Buried in Treasures Workshop: waitlist control trial of facilitated support groups for hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2012 Nov;50(11):661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilliam CM, Norberg MM, Villavicencio A, Morrison S, Hannan SE, Tolin DF. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder: an open trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011 Nov;49(11):802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muroff J, Steketee G, Rasmussen J, Gibson A, Bratiotis C, Sorrentino C. Group cognitive and behavioral treatment for compulsive hoarding: a preliminary trial. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(7):634–640. doi: 10.1002/da.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steketee G, Frost RO, Tolin DF, Rasmussen J, Brown TA. Waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy for hoarding disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2010 May;27(5):476–484. doi: 10.1002/da.20673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007 Jul;45(7):1461–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolin DF, Stevens MC, MNA, Villavicencio AL, Morrison S. Neural mechanisms of cognitive behavioral therapy response in Hoarding Disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2012;1:180–188. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner K, Steketee G, Nauth L. Treating elders with compulsive hoarding: a pilot program. Cog Behav Pract. 2010;17:449–457. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, Baxter LR., Jr Paroxetine treatment of compulsive hoarding. J Psychiatr Res. 2007 Sep;41(6):481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez CI, Bender J, Jr, Morrison S, Mehendru R, Tolin D, Simpson HB. Does extended release methylphenidate help adults with hoarding disorder?: a case series. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013 Jun;33(3):444–447. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318290115e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedman AS. Using the SMOG formula to revise a health-realted document. Am J Health Educ. 2008;39(1):61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ley P, Florio T. The use of readability formulas in health care. Psychol Health Med. 1996;1(1):7–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel SR, Simpson HB. Patient preferences for obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010 Nov;71(11):1434–1439. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05537blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Muroff J. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Hoarding Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2015 Jan 14; doi: 10.1002/da.22327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Tang L, Wells KB. Can quality improvment programs for depression in primary care adress patient preferences for treatment? Med Care. 2001;39(9):934–944. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angelo FN, Miller HE, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. “I need to talk about it”: a qualitative analysis of trauma-exposed women’s reasons for treatment choice. Behav Ther. 2008 Mar;39(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy-Byrne P, Berliner L, Russo J, Zatzick D, Pitman RK. Treatment preferences and determinants in victims of sexual and physical assault. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003 Mar;191(3):161–165. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000055343.62310.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zoellner LA, Feeny NC, Cochran B, Pruitt L. Treatment choice for PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2003 Aug;41(8):879–886. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis C, Pearce J, Bisson JI. Efficacy, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of self-help interventions for anxiety disorders: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2012 Jan;200(1):15–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bevan A, Oldfield VB, Salkovskis PM. A qualitative study of the acceptability of an intensive format for the delivery of cognitive-behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Clin Psychol. 2010 Jun;49(Pt 2):173–191. doi: 10.1348/014466509X447055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knopp-Hoffer J, Knowles S, Bower P, Lovell K, Bee PE. ‘One man’s medicine is another man’s poison’: a qualitative study of user perspectives on low intensity interventions for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saxena S. Recent advances in compulsive hoarding. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008 Aug;10(4):297–303. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saxena S, Sumner J. Venlafaxine extended-release treatment of hoarding disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014 Sep;29(5):266–273. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raue PJ, Schulberg HC, Heo M, Klimstra S, Bruce ML. Patients’ depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: a randomized primary care study. Psychiatr Serv. 2009 Mar;60(3):337–343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.