Abstract

In mammals, nitric oxide synthases (NOSs) produce nitric oxide for signaling and defense functions; in Streptomyces, NOS proteins nitrate a tryptophanyl moiety in synthesis of a phytotoxin. We have discovered that the NOS protein from the radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans (deiNOS) associates with an unusual tryptophanyl tRNA synthetase (TrpRS). D. radiodurans contains genes for two TrpRSs: the first has ≈40% sequence identity to typical TrpRSs, whereas the second, identified as the NOS-interacting protein (TrpRS II), has only ≈29% identity. TrpRS II is induced after radiation damage and contains an N-terminal extension similar to those of proteins involved in stress responses. Recombinantly expressed TrpRS II binds tryptophan (Trp), ATP, and D. radiodurans tRNATrp and catalyzes the formation of 5′ adenyl-Trp and tRNATrp, with approximately five times less activity than TrpRS I. Upon coexpression in Escherichia coli, TrpRS II binds to, copurifies with, and dramatically enhances the solubility of deiNOS. Dimeric TrpRS II binds dimeric deiNOS with a stoichiometry of 1:1 and a dissociation constant of 6–30 μM. Upon forming a complex, deiNOS quenches the fluorescence of an ATP analog bound to TrpRS II, and increases its affinity for substrate l-arginine. Remarkably, TrpRS II also activates the NOS activity of deiNOS. These findings reveal a link between bacterial NOS and Trp metabolism in a second organism and may indicate yet another novel biological function for bacterial NOS.

Nitric oxide synthases (NOSs) are highly regulated enzymes that synthesize the potent cytotoxin and signal molecule nitric oxide (NO) from l-arginine (l-arg) (1–3). In mammals, NOSs are responsible for many functions that range from protection against pathogens and tumor cells to blood pressure regulation and nerve transmission. Bacterial NOS proteins also catalyze the heme-dependent conversion of l-arg to NO in vitro (4–7); however, in at least one case, they have been shown to function in the nitration of secondary metabolites (8). Mammalian NOSs are homodimers that contain an N-terminal heme oxygenase domain and a C-terminal flavoprotein reductase domain. The catalytic oxygenase domain binds l-arg, heme and the redox-active cofactor 6R-tetrahydrobiopterin, whereas the electron-supplying reductase domain binds FAD, FMN, and NADPH.

Bacterial NOSs from Deinococcus radiodurans (deiNOS), Staphylococcus aureus (saNOS), and Bacillus subtilis (bsNOS) are homologous to the mammalian N-terminal heme oxygenase domain but lack an associated C-terminal flavoprotein reductase domain and N-terminal regions that bind Zn2+, the dihydroxypropyl side chain of 6R-tetrahydrobiopterin, and the adjacent subunit of the dimer (4, 6, 9). Nevertheless, deiNOS, bsNOS, and saNOS are dimeric, have a normal heme environment, bind substrate l-arg, and produce nitrogen oxide species in a manner dependent on pterin (either with 6R-tetrahydrobiopterin or with the related cofactor tetrahydrofolate (4, 5, 7). Conservation of key residues among bacterial and mammalian NOSs also suggests that all bacterial NOSs produce nitrogen oxides from l-arg and the NOS intermediate Nω-hydroxy-l-arginine (NHA) (6, 9). bsNOS has been directly shown to produce nitric oxide (5).

The first biological function for a bacterial NOS was determined for Streptomyces (8). Pathogenic Streptomyces species (Streptomyces scabies, Streptomyces acidiscabies, Streptomyces turgidiscabies, and Streptomyces ipomoea) produce a family of unusual nitrated cyclic dipeptides [derivatives of cyclo-(l-tryptophanyl-l-phenylalanyl)], called thaxtomins (10), that contain a 4-nitro-tryptophanyl moiety and interfere with the formation of plant cell walls (11). A large pathogenicity island that contains the nonribosomal peptide synthase genes responsible for production of the thaxtomin dipeptide also codes for an NOS. Genetic and isotope labeling studies have shown that the Streptomyces NOS participates in thaxtomin nitration, although the chemical mechanism of nitration is currently unknown (8).

We report that, in D. radiodurans, an unusual tryptophanyl tRNA synthetase (TrpRS) interacts with NOS, increases NOS solubility, affinity for substrate, and NOS activity. It is compelling that another bacterial NOS associates with a protein involved in Trp metabolism. The biophysical properties of the complex presented here set the stage for an in-depth study of its chemical reactivity.

Experimental Procedures

Pull-Down Assays. D. radiodurans (ATCC no. 13939) was grown in TGY media until logarithmic phase. After harvesting by centrifugation, cells were resuspended in buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/20 mM NaCl) to a density of ≈0.5 g/ml and sonicated. After centrifugation at 75,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was precleared by incubating 500-μl aliquots with 30 μl of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin for 30 min at 4°C with agitation. His-tagged NOS was bound to Ni-NTA resin (≈10 μg protein to 30 μl of 50% bead suspension) and incubated with precleared cell lysate for1hat4°C with agitation. Samples were spun down and the beads washed three times with lysis buffer. Beads were heated in sample buffer for 7 min at 70°C and analyzed by SDS/PAGE.

Peptide Mass Fingerprinting (PMF). In-gel digests were performed overnight at 37°C in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate by using porcine trypsin (Promega sequencing grade). Mass data were obtained on an Applied Biosystems 4700 proteomics analyzer (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time-of-flight MS analysis) operating in positive ion reflector mode. Data were analyzed by using the search engine Mascot, which can be accessed at www.matrixscience.com.

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of TrpRS I and II. Genes encoding TrpRS I and II were PCR-amplified from D. radiodurans genomic DNA. PCR fragments were subcloned into pET28 (Novagen). Proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21-DE3 cells) after induction with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside for 4–5 h at 28°C. Proteins were purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, digested with thrombin, and eluted from a Superdex 200 sizing column. Proteins were concentrated in 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5)/150 mM NaCl.

Protein Concentrations. Protein concentrations for TrpRS II were determined from extinction coefficients at 280 nm (ε280 = 10,000 M–1) calculated from the protein sequence and confirmed by using a RC-DC assay (Bio-Rad). dieNOS concentrations were determined by using ε400 = 70,000 M–1·cm–1 for l-arg bound protein and ε428 = 100,000 M–1·cm–1 for imidazole bound protein (4), and confirmed with a bicinchoninic acid assay.

Preparation of tRNATrp Transcript. The tRNATrp gene, identified in the D. radiodurans genome by the program trnascan, was PCR-cloned with P. furiosus polymerase and purified with PCR purification kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Introduction of a T7 promoter in the 5′ end of the construct enabled amplification by in vitro transcription by using T7-MEGA shortscript high-yield transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). The resulting tRNATrp was purified by using an Rnaid kit (Q-Biogene), concentrated by isopropanol precipitation, and resuspended in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5).

Coexpression and Copurification of TrpRS II and deiNOS. TrpRS II was subcloned without an affinity tag in pACYC, a plasmid with a unique origin of replication compatible with pET28a. pACYC-containing TrpRS II was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) already containing His6-tagged deiNOS cloned into pET15b (4). Proteins were expressed and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography and gel filtration as described above.

Determination of the Dissociation Constants for TrpRS II and 2,4,6,-trinitrophenyl (TNP)-ATP or ATP. Enhancement of the fluorescence of the ATP analog TNP-ATP (excitation = 475 nm and emission = 540 nm on a PerkinElmer LS55 luminescence spectrometer) upon binding TrpRS II was analyzed at different protein concentrations by following the method of Bujalowski and Lowman (12). To determine an approximate binding constant for ATP, TrpRS II was titrated against concentrations of TNP-ATP (4–24 μM) in the absence and presence of 4 μM ATP. Binding isotherms for TNP-ATP were fit to the expression

|

[1] |

where Sb is the concentration of ATP bound, Sf is the concentration of free ATP, and K1 and K2 are the first and second dissociation constants of TNP-ATP for TrpRS II. Dissociation constants in the absence of ATP (Ktrue) and in the presence of ATP (Kapp) were used to calculate the dissociation constant of ATP (Ki) with Eq. 2, where Ktrue was estimated as (K1K2)1/2:

|

[2] |

Determination of the Binding Constant for TrpRS II to deiNOS by Fluorescence Quenching. TrpRS II [11 μM (dimeric) in 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/50 mM NaCl] was mixed with TNP-ATP (12 μM) and titrated against various concentrations (5.0–45 μM) of deiNOS (0.5 mM in 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/500 mM NaCl/200 mM imidazole/250 mM sucrose). Fluorescence quenching was monitored until saturation. Background corrections were made at each TNP-ATP concentration to account for any inner-filter effects of deiNOS.

Binding isotherms were fit to the following equation:

|

[3] |

where Sb is the concentration of deiNOS dimer bound to TrpRS, N is the number of binding sites, Sf is the concentration of free NOS dimer, and Kd is the binding constant of TrpRS II and deiNOS.

Measurement of deiNOS Activity. deiNOS activity was measured by using the peroxidase shunt assay with NHA as a substrate (13). deiNOS (10 μM dimer) was incubated with l-NHA (0.5 mM) in the absence or presence of TrpRS II (50 μM dimer) at room temperature for 15 min in 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5)/150 mM NaCl. After adding H2O2 (10 mM) and waiting 10 min, the Griess reagents (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) were added, and absorbance was measured at 540 nM.

Arginine Binding to deiNOS in the Presence and Absence of TrpRS. l-arg binding to deiNOS was measured by following the spectral shift of the Soret band from 428 to 400 nm that accompanies displacement of imidazole from a NOS heme by l-arg (14–16). DeiNOS {40 μM in 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.5)/100 mM NaCl/40 mM sucrose/50 mM imidazole/TrpRS II–deiNOS complex [40 μM in 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.5)/100 mM NaCl/50 mM sucrose/40 mM imidazole]} were concurrently titrated against various concentrations of l-arg (0–100 μM), and the increment in absorbance at 400 nm was recorded until saturation. Apparent binding constants were obtained with double reciprocal plot analysis.

Perturbation of Arginine Binding to deiNOS by TrpRS II. deiNOS [18 μM in 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5)/500 mM NaCl/200 mM imidazole/0.25 M sucrose] was treated with 10 mM l-arg and incubated with various concentrations of TrpRS II (0–250 μM) at room temperature for 30 min. Difference spectra were recorded between deiNOS alone and samples containing various concentrations of TrpRS II. Corrections were made to account for the increased solubility of deiNOS in presence of TrpRS II.

Gel-Shift Assay for tRNA Binding to TrpRS II. We incubated 10 μM tRNATrp with 20 μM TrpRS II for 30 min at 25°C. Similar samples were made with deiNOS (20 μM) alone and with the complex (20 μM). Five microliters of each sample was electrophoresed on a 2.5% agarose gel [running buffer: TAE containing 30 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM acetic acid, and 2 mM EDTA] and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Assays. As described (17), a 0.25-ml mixture containing 100 mM potassium bicine (pH 8.8), 5.0 mM MgCl2, 4.0 mM reduced glutathione, 2.5 mM chloroquine, 1.0 mM ATP, 1 μM tRNATrp, and 0.1 mM l-5-[3H]Trp [250 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq), 9.25 MBq, Moravek Radiochemicals, Brea, CA] were incubated at 37°C for 5 min and TrpRS II or I added to a final concentration of 10 μM. After 30 min at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.7 ml of 12:1 (vol/vol) cold 95% ethanol-2 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0. The tryptophanyl tRNA was precipitated with 2 M HCl while the reaction mix was cooled to 4°C, filtered by using glass fiber filters, and washed five times with 2 ml of 2 M HCl. Filters were added to scintillation fluid and counted with a Beckman L51801 scintillation counter.

PPi Assay. An EnzChek PPi assay kit was used to follow adenyl Trp formation by monitoring release of PPi. Following the protocol of Lloyd et al. (18), 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methyl purine ribonucleoside (0.2 mM), ATP (1 mM), Trp (1 mM), and TrpRSI or II were mixed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM sodium azide. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase (1 unit) and inorganic pyrophosphatase (0.03 units) were added, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 25°C. Absorbance was measured at 355 nm to determine PPi release.

Results

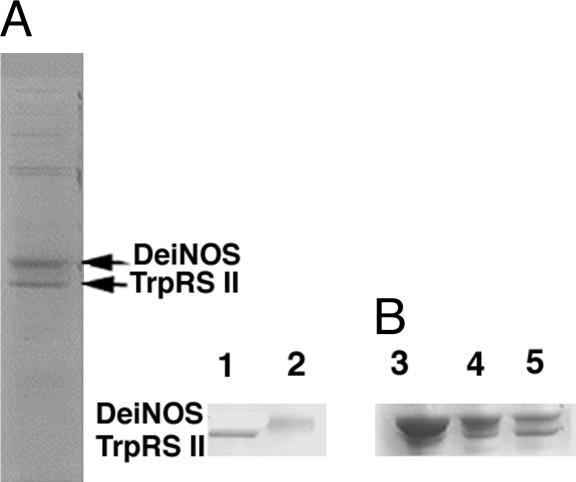

deiNOS Interacts with TrpRS II in D. radiodurans Cell Lysates. In efforts to elucidate NOS function in bacteria other than Streptomyces, we performed a series of pull-down experiments where affinity-tagged recombinant NOSs were incubated with cell lysates from their source organisms and then precipitated with Sepharose beads targeted to the affinity labels. His6-tagged deiNOS (42 kDa) bound to Ni-NTA beads consistently associated with a protein of similar molecular mass (38.6 kDa) from D. radiodurans lysate prepared from log-phase cells (Fig. 1A). No such band was observed when NTA beads alone were spun through supernatant. The copurifying band was excised from the gel, digested with trypsin, and identified by PMF with knowledge of the D. radiodurans genome sequence. Fourteen of the masses in the PMF obtained agreed with the predicted masses for a protein of a molecular mass of 38.2 kDa to give 49% coverage with an rms error of 398 ppm. The interacting protein was identified as one of the two TrpRSs in the D. radiodurans genome, hereafter referred to as TrpRS II. To investigate whether deiNOS itself was present under the same conditions, recombinant affinity-labeled TrpRS II was demonstrated to copurify a band on SDS/PAGE of molecular mass consistent with deiNOS (Fig. 1B). Sixteen of the masses in the resulting PMF agreed with the masses predicted for deiNOS, giving 33% sequence coverage with an rms error of 319 ppm. In addition, D. radiodurans cell lysate was also passed over a Sepharose column modified with the NOS substrate l-arg. After elution with l-arg, multiple bands were resolved on SDS/PAGE and one at the appropriate molecular mass was identified as deiNOS by PMF. Thus, both deiNOS and TrpRS II are expressed in D. radiodurans, and they interact with each other.

Fig. 1.

deiNOS and TrpRS II interact in D. radiodurans supernatant. (A) SDS/PAGE gel of affinity-tagged deiNOS incubated and precipitated from D. radiodurans supernatant taken from log-phase cells. The lower molecular weight band was shown by MS fingerprinting to be TrpRS II. (B) Affinity-tagged TrpRS II pulls down native deiNOS from cell supernatant. Lanes: 1, recombinant TrpRS II; 2, recombinant deiNOS; 3, recombinant TrpRS II pulls down deiNOS; 4, recombinant deiNOS pulls down TrpRS II; 5, recombinant TrpRS II and recombinant deiNOS are shown for comparison.

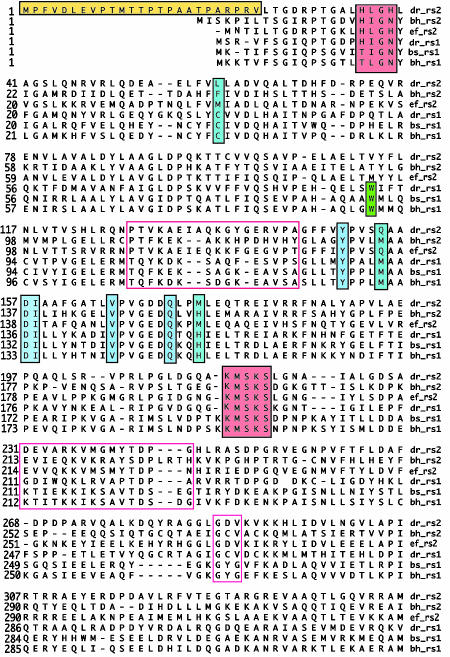

D. radiodurans Contains Two TrpRS Proteins. Analysis of the D. radiodurans genome revealed two genes identified as TrpRSs. The first (TrpRS I) has ≈40% sequence identity with other TrpRS proteins from bacteria that contain only one such synthetase; TrpRS II has only 29–33% sequence identity with TrpRS I and other related synthetases (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, TrpRS II conserves residues of standard Trp synthetases important for binding ATP and Trp (Fig. 2). In particular, TrpRS II has Asp at position 157 and a hydrophobic residue at 166 (Val), which are two key positions that discriminate Trp over other amino acids (Fig. 2) (19). In addition, TrpRS II contains an unusual N-terminal extension with significant homology to N-terminal sequences of proteins from the survival E family (20) (Fig. 2). blast genome searches indicate that some other prokaryotes also contain two TrpRS proteins and that the second synthetase in these organisms typically has ≈50% identity with D. radiodurans TrpRS II. One such TrpRS II from Streptomyces coelicolor confers resistance to the TrpRS inhibitor indolemycin (21). Although bacterial NOSs have only so far been found in a limited number of mostly Gram-positive bacteria, many of these organisms (Bacillus halodurans, Streptomyces avermitilis, Bacillus anthracis, Staphylococcus pyogenes, and D. radiodurans) but not all (Bacillus stearothermophilus, Exiguobacterium, and Bacillus subtilis) also contain a TrpRS II in their genomes.

Fig. 2.

Sequence alignment of three TrpRS I proteins and three TrpRS II proteins. TrpRS I (rs1) and II (rs2) sequences are shown from D. radiodurans (dr), B. halodurans (bh), Enterococcus faecalis (ef), and B. stearothermophilus (bs). Residues key to binding Trp (dark blue) and ATP (red) are well conserved in both families, although there are some differences between TrpRS I and II in residues within a few angstroms of the Trp-binding site (light blue). Putative tRNA-binding regions in TrpRS I sequences (red boxes) are not well conserved by TrpRS II. TrpRS II sequences do not contain Trp, even at a position where Trp is conserved in TrpRS I (green). D. radiodurans TrpRS II has an unusual N-terminal extension that contains a sequence homologous to that of the stress-response protein survival E (yellow).

TrpRS II Is a Dimer That Binds Two ATP Molecules Cooperatively. The fluorescence of the ATP analog TNP-ATP enhances on binding TrpRS II. Titrating TNP-ATP and monitoring fluorescence enhancement at multiple protein concentrations determined that the fluorescence change on binding was proportional to the total amount of TNP-ATP bound (12). The TNP-ATP-binding isotherms fit better to an expression (Eq. 1) that allows for a small degree of cooperativity between the two binding sites (Eq. 1: KD1 = 3.3 μM and KD2 = 0.8 μM) rather than a model that assumes identical sites (KD1 = 1/4KD2; Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). ATP inhibits the binding of TNP-ATP. A competitive inhibition model (Eq. 2) predicts an approximate dissociation constant for ATP that is slightly higher (9 μM) than that for TNP-ATP (Fig. 7), but considerably lower than that observed for more typical tRNA synthetases (17, 22).

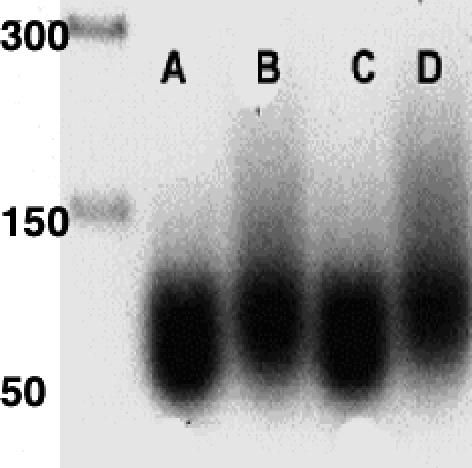

TrpRS II Binds tRNATrp. We tested the ability of TrpRS II to bind tRNATrp, produced by in vitro transcription of a synthetic D. radiodurans tRNATrp gene. In an agarose gel-shift assay, TrpRS II shifts the band corresponding to tRNATrp to higher molecular mass (Fig. 3). No such shift was observed when deiNOS (or bsNOS) was incubated with tRNATrp; however, if both TrpRS II and deiNOS are added together to tRNATrp, an even greater shift occurs, which suggests that TrpRS II may bind tRNATrp and deiNOS simultaneously.

Fig. 3.

TrpRS II binds tRNATrp. Lanes (from left to right): DNA base molecular mass ladder; A, tRNATrp; B, TrpRS II plus tRNATrp; C, deiNOS plus tRNATrp; D, deiNOS–TrpRS II complex plus tRNATrp.

TrpRS II Adenylates Trp and Charges tRNA with Activities Lower than Those of TrpRS I. Before tRNA charging, tRNA synthetases activate amino acids by reacting their carboxylate groups with ATP to form a5′ acyl adenylate and release PPi. Neither TrpRS I nor II released PPi in the absence of Trp. In the presence of 1 mM Trp, both enzymes released PPi, although TrpRS I was approximately five times more active than TrpRS II (Table 1). No significant change in PPi release activity was observed in the presence of tRNATrp for either TrpRS I or II (Table 1). tRNA charging by TrpRS I and II was assayed by monitoring [3H]Trp coupling to tRNA. tRNA charging activity corresponds to the respective adenylation activities for both enzymes, with TrpRS I having an activity approximately five times that of TrpRS II under saturating conditions for substrates (Table 1). The activity of TrpRS I matches reasonably well with that found for E. coli TrpRS (17, 22). Thus, in vitro transcription produces a suitable tRNATrp substrate for both TrpRS I and II. Importantly, TrpRS II can charge tRNA, but not with the same efficiency as TrpRS I.

Table 1. Activities of D. radiodurans TrpRS I and II.

deiNOS and TrpRS II Copurify During Heterologous Expression. When His6-tagged deiNOS and untagged TrpRS II were coexpressed in E. coli and purified by Ni-NTA affinity column, both proteins bind and elute together (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). When the Ni-NTA-purified proteins were further chromatographed by size exclusion (Superdex 200 column), the TrpRS II eluted a volume consistent with a molecular mass of a 1:1 complex between TrpRS II and deiNOS and not at the volume where TrpRS II elutes alone (Fig. 8). Because deiNOS and TrpRS II have similar molecular masses, TNP-ATP fluorescence enhancement by TrpRS II was monitored to confirm the presence of TrpRS II in early fractions when coeluted with deiNOS.

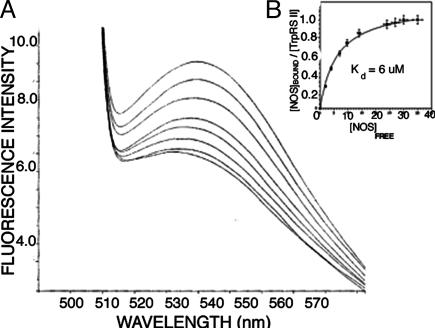

deiNOS Binding to TrpRS II Quenches the Fluorescence of TNP-ATP. Titration of TNP-ATP-bound TrpRS II with deiNOS quenches the TNP-ATP fluorescence in a manner that saturates when the two proteins are in equal molar ratio (Fig. 4). Fitting these data to a modified form of the Scatchard equation (Eq. 3) reveals that one deiNOS dimer binds one TrpRS dimer with a dissociation constant of 6.0 μM and a stoichiometry (N value) of 1.1 (Fig. 4). No quenching of TNP-ATP was observed with deiNOS alone or on titration of TrpRS II with bsNOS. Chromatography on a Superose12 sizing column confirmed that both deiNOS and TrpRS are dimeric at the concentrations of the binding experiments. Thus, deiNOS not only binds TrpRS II with an affinity that is physiologically relevant, but deiNOS binding affects the properties of the TrpRS II ATP-binding site.

Fig. 4.

Binding of deiNOS to TrpRS II as monitored by TNP-ATP quenching. (A) Raw fluorescence data for titration of TrpRS II–TNP-ATP with deiNOS. (B) Binding isotherm for deiNOS to TrpRS II derived from A gives a Kd of 6 μM.

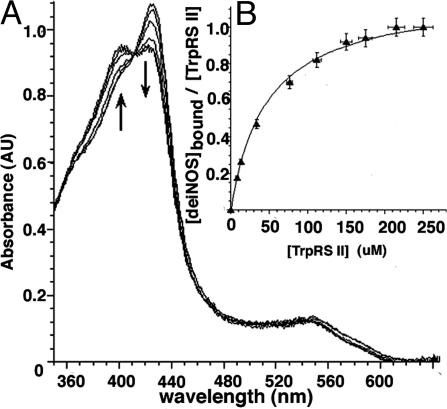

TrpRS II Enhances deiNOS Substrate Binding. An early indication that deiNOS and TrpRS II are physiological partners was the observation that the solubility of recombinantly expressed deiNOS increases from 4 mg/ml [in 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5)/500 mM NaCl/200 mM imidazole) to 16 mg/ml in presence of TrpRS II. Moreover, deiNOS in complex with TrpRS II has a higher affinity for substrate l-arg than deiNOS alone (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). deiNOS alone is soluble at concentrations greater than ≈2mg/ml only under certain conditions; we found 40 mM sucrose and 50 mM imidazole to be especially effective at stabilizing the protein. Under these conditions, the apparent affinity of deiNOS for l-arg drops considerably (19 mM vs. 90 μM), as it also does for bsNOS. This result may be partly due to competition between l-arg and imidazole for the deiNOS active center. Nevertheless, to ensure soluble protein, high sucrose/imidazole conditions were maintained to evaluate the effect of TrpRS II on deiNOS l-arg affinity. We monitored l-arg binding to deiNOS by following the type I spectral shift in the deiNOS heme Soret peak from 428 to 400 nM that accompanies the exchange of imidazole for l-arg in the deiNOS heme center. deiNOS binds l-arg with a slightly higher affinity in the complex (9 mM) than in isolation (19 mM). Because the deiNOS–TrpRS II complex binds l-arg better than deiNOS, the enhancement in l-arg binding on titration with deiNOS gives an apparent association constant for the complex (Fig. 5). Titrating deiNOS with TrpRS II at concentrations where deiNOS is not initially saturated with l-arg increases l-arg binding until a 1:1 complex forms (Fig. 5). Scatchard analysis produces an apparent dissociation constant of 30 μM, in reasonable agreement with the 6 μM value from TNP-ATP fluorescent quenching data (Fig. 4). The higher affinity in the latter case may result from the presence of nucleotide.

Fig. 5.

Binding of deiNOS to TrpRS II monitored by increase in deiNOS substrate affinity. (A) Increase in l-arg binding to deiNOS upon addition of TrpRS II as monitored by increasing absorbance at 400 nm and decreasing absorbance at 428 nm; isobestic point at 410 nm. (B) Binding isotherm corresponding to A. Fit to Eq. 3 produces a Kd of 30 μM.

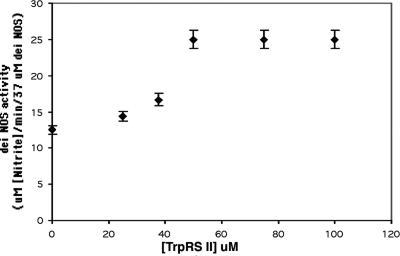

TrpRS II Enhances deiNOS NOS Activity. deiNOS catalyzes the conversion of NHA and peroxide to  , an end product of NO or related species reacting in oxygenated solution (4). Titration of deiNOS with TrpRS II increases nitrite production until a stoichiometric complex forms (Fig. 6), at which point the NOS activity is approximately two to three times greater than in the absence of TrpRS II. Under these conditions, increasing NHA does not increase nitrite production by free deiNOS. In both the presence and absence of TrpRS II, deiNOS activity is constant with time (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). DeiNOS activation is not seen with TrpRS I or stabilizing agents such as BSA. Thus, TrpRS II activates the catalytic activity of deiNOS, in addition to influencing substrate affinity.

, an end product of NO or related species reacting in oxygenated solution (4). Titration of deiNOS with TrpRS II increases nitrite production until a stoichiometric complex forms (Fig. 6), at which point the NOS activity is approximately two to three times greater than in the absence of TrpRS II. Under these conditions, increasing NHA does not increase nitrite production by free deiNOS. In both the presence and absence of TrpRS II, deiNOS activity is constant with time (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). DeiNOS activation is not seen with TrpRS I or stabilizing agents such as BSA. Thus, TrpRS II activates the catalytic activity of deiNOS, in addition to influencing substrate affinity.

Fig. 6.

TrpRS II activates deiNOS NOS activity. Under saturating substrate conditions, the amount of nitrite produced by deiNOS from NHA and peroxide increases as the complex with TrpRS II forms.

Discussion

We have determined that the D. radiodurans NOS protein interacts in vitro and in vivo with TrpRS II that has somewhat unusual properties. Interestingly, TrpRS II appears to be auxiliary to the protein synthesis machinery because D. radiodurans has another synthetase (TrpRS I) with higher tRNA charging activity and sequence homology to proteins that are the sole TrpRSs in their source organisms. Sequence analyses of TrpRS II assign it to a class of synthetase found in organisms that also contain a more traditional TrpRS. TrpRS II conserves key residues involved in binding Trp and ATP (Fig. 2), but there are also some substitutions in the Trp-binding regions that delineate TrpRS II sequences from those of TrpRS I (Fig. 2, light green boxes). For example, in TrpRS II, a larger hydrophobic residue substitutes for a conserved cysteine of TrpRS I that is within a few angstroms of the Trp-binding site (Trp-40 in D. radiodurans). Structural studies on B. stearothermophilus and human enzymes have revealed a two-domain structure for TrpRS (23, 24). The Trp- and ATP-binding sites lie in a cleft between a larger N-terminal domain with a Rossman fold and a smaller C-terminal domain with a mostly helical structure. The N-terminal domain binds the tRNA acceptor stem whereas, the C-terminal domain recognizes the tRNA anti-codon loop (24). TrpRS dimerizes through the N-terminal domain and the two active centers of the dimer influence each other during ligand binding (22, 25–27). Thus, it is not unreasonable that TrpRS II shows some cooperativity in binding TNP-ATP. Although there is no structure for a TrpRS bound to tRNA, analogies with the tRNA-bound structure of TyrRS have implicated specific regions of TrpRS for tRNA interactions (24). Interestingly, these sequence motifs are not well conserved by the TrpRS II enzymes (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, TrpRS II does catalyze both the adenylation of Trp and the charging of D. radiodurans tRNATrp, albeit with activities less than those of D. radiodurans TrpRS I, which has activities typical of other bacterial TrpRSs (Table 1). As found for yeast and bovine TrpRS, (28), in vitro transcribed tRNATrp is a good substrate for TrpRS I and II despite lacking posttranscriptional modifications. Unlike the E. coli TrpRS (17), but consistent with many other type I synthetases (29), tRNA-binding does not activate the adenylation reaction for either D. radiodurans TrpRS I or TrpRS II.

The association of TrpRS II with deiNOS likely relates to the biological function of these two proteins. The proteins interact in D. radiodurans cell lysate, preferentially associate when coexpressed, and TrpRS II significantly enhances deiNOS stability and solubility. The proteins bind each other with a 1:1 ratio and a dissociation constant of physiological relevance (6–30 μM). This affinity is within the range found for nonobligate dimers (30). Consistent with a functional complex, the active center properties of both deiNOS and of TrpRS II respond to association of the two proteins. deiNOS quenches the fluorescence of TrpRS II-bound TNP-ATP and TrpRS II increases the affinity of deiNOS for substrate and stimulates its NO synthase activity. Under these assay conditions, where the proteins are stable, the l-arg affinity and NO synthase activities of dieNOS increase only modestly with TrpRS II. Nevertheless, taken with the TNP-ATP data, these changes indicate that each protein influences the properties of the others active center. Because both deiNOS and TrpRS II are dimers, this probably requires juxtaposition of their active centers by alignment of their respective dimer twofold axes. Increasing the sequestration of the active centers in both proteins could generate a higher binding affinity for l-arg in NOS and perturb the TNP-ATP fluorescence in TrpRS II. In other NOS proteins, degree of solvation affects properties of the heme center (15, 16, 31). Alternatively or additionally, conformational effects could propagate from the interaction site to the active centers.

What then could be the functional consequence of a NOS associating with tRNA synthetase? deiNOS has interesting parallels to the Streptomyces NOS that nitrates the phytotoxin thaxtomin (8). The txtA and txtB peptide synthases responsible for thaxtomin nitration first adenylate their amino acids before condensing them into the nonribosomal cyclic peptide backbone of thaxtomin (32). Notably, the site of nitration in thaxtomin is a Trp indole ring. deiNOS then also associates with a protein involved in Trp metabolism that catalyzes Trp adenylation. Thus, TrpRS II possibly functions to supply deiNOS with adenylated Trp for subsequent nitration or nitrosylation. This product may be a component of a biosynthetic pathway that produces a yet-to-be-discovered secondary metabolite. Alternatively, TrpRS II may act on a form of Trp modified by deiNOS. Interestingly, TrpRS II does not contain any Trp residues. Even a position where Trp is completely conserved in TrpRS I contains an aliphatic hydrophobic residue in TrpRS II (Fig. 2, green box). Association with a functional deiNOS will sensitize TrpRS I to nitration and Trp residues will be susceptible to modification. Perhaps these residues have been selected against because of the proximity of NOS-generated reactive nitrogen species. This result may also explain why the conserved cysteine in the active center of TrpRS I has been changed to a hydrophobic residue in TrpRS II. It has been well demonstrated in myoglobin and peroxidases that heme proteins catalyze nitration of their aromatic residues when nitric oxide or other oxidized nitrogen species are available (33–37).

TrpRS II charges tRNA with Trp, a reaction that could take place before or after Trp nitration. The Trp-binding site of TrpRS II has enough residue substitutions to make use of an alternative substrate possible and tRNA appears to bind to the TrpRS II–deiNOS complex. Involvement of tRNA does not necessarily implicate deiNOS with protein synthesis. tRNA synthetases are known to participate in a wide variety of biological functions in addition to protein synthesis, including intercellular signaling in mammals and heme biosynthesis in plants, algae, and some bacteria (38–40). For example, In the heme biosynthesis of plants, the pyrrole ring precursor δ-aminolevulinic acid derives directly from glutamyl-tRNA (40). Furthermore, Archaea contain a second, truncated tRNA synthase that converts aspartic acid to asparagine (41). Bacteria of the Thermus/Deinococcus group transamidate asparaginyl-tRNA to derive aspartate (42). Another truncated synthetase in E. coli adds glutamate to tRNAAsp, for an unknown reason (43, 44). Thus, there is precedent for D. radiodurans TrpRS II acting in a previously uncharacterized biosynthetic pathway.

D. radiodurans is well known for its amazing ability to withstand ionizing radiation and desiccation (45). Such attributes arise from an efficient DNA-repair system. Analysis of its transcriptome after radiation exposure reveals large-scale induction of genes involved in chromosome restructuring (46). The expression levels of TrpRS II (DR1093) increases 2.2-fold, 5 h after radiation exposure, and then return to near base line 5 h later. This temporal pattern of expression parallels that of enzymes involved in the repair response, such as RecA (www.esd.ornl.gov/facilities/genomics). Most other tRNA-synthetase genes, including TrpRS I, show no significant change in expression levels after exposure to radiation. A stress-response-related function for TrpRS II may also be indicated by its N terminus, resembling that of the survival E protein, a phosphatase that participates in prokaryotic stress responses (20). In contrast, deiNOS (DR2597) expression decreases after exposure (>10-fold) and then slowly recovers to preexposure levels >20 h later. This pattern of response is found for other proteins involved in growth-related metabolism and may include enzymes participating in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. Although these experiments measure message levels and not protein levels, they do suggest that TrpRS II may not always associate with deiNOS and perhaps has multiple functions in D. radiodurans, as do some mammalian tRNA synthetases (39, 47).

In conclusion, we have discovered that a bacterial NOS protein interacts with an unusual and auxiliary TrpRS that appears to have some role in the DNA-repair response of D. radiodurans. Furthermore, there are parallels between the activities of TrpRS II and the txtA and txtB peptide synthases from a Streptomyces phytotoxin biosynthesis pathway where another bacterial NOS functions to nitrate a Trp moiety. Whether the complex of deiNOS and TrpRS II catalyzes the nitration of Trp or a Trp derivative and whether there is any link between tRNA and NOS activity are important questions to be addressed. Nonetheless, the deiNOS–TrpRS II interaction provides yet another twist in efforts to understand the scope of biological functions elicited by NOS proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Klaas Van Wijk, Guilia Friso, Brian Lawhorn, John Lis, and Hua Shi for assistance with initial experiments, and Joe Zhou and Robert Liu (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN) for sharing transcriptome data. This work was supported by Petroleum Research Fund Grant 38374-AC (to B.R.C.)

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: NOS, NO synthase; deiNOS, bacterial NOS from Deinococcus radiodurans; bsNOS, bacterial NOS from Bacillus subtilis; TrpRS, tryptophanyl tRNA synthetase; l-arg, l-arginine; NHA, Nω-hydroxy-l-arginine; NTA, nitrilotriacetic acid; TNP, 2,4,6,-trinitrophenyl; PMF, peptide mass fingerprinting.

Note Added in Proof. The deiNOS–TrpRSII complex has now been shown to catalyze the specific nitration of Trp (48).

References

- 1.Alderton, W. K., Cooper, C. E. & Knowles R. G. (2001) Biochem. J. 357, 593–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeiffer, S., Mayer, B. & Hemmens, B. (1999) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 1715–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffith, O. W. & Stuehr, D. J. (1995) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 57, 707–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adak, S., Bilwes, A. M., Panda, K., Hosfield, D., Aulak, K. S., McDonald, J. F., Tainer, J. A., Getzoff, E. D., Crane, B. R. & Stuehr, D. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adak, S., Aulak, K. & Stuehr, D. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16167–16171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bird, L. E., Ren, J. S., Zhang, J. C., Foxwell, N., Hawkins, A. R., Charles, I. G. & Stammers, D. K. (2002) Structure (Cambridge, Mass.) 10, 1687–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong, I. S., Kim, Y. K., Choi, W. S., Seo, D. W., Yoon, J. W., Han, J. W., Lee, H. Y. & Lee, H. W. (2003) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 222, 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kers, J. A., Wach, M. J., Krasnoff, S. B., Widom, J., Cameron, K. D., Bukhalid, R. A., Gibson, D. M., Crane, B. R. & Loria, R. (2004) Nature 429, 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pant, K., Bilwes, A. M., Adak, S., Stuehr, D. J. & Crane, B. R. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 11071–11079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King, R. R., Lawrence, C. H., Clark, M. C. & Calhoun, L. A. (1989) J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 13, 849–850. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fry, B. A. & Loria, R. (2002) Phys. Mol. Plant Pathol. 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bujalowski, W. & Lohman, T. M. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 3099–3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hevel, J. M. & Marletta, M. A. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 233, 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adak, S. & Stuehr, D. J. (2001) J. Inorg. Biochem. 83, 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh, D. K., Crane, B. R., Ghosh, S., Wolan, D., Gachhui, R., Crooks, C., Presta, A., Tainer, J. A., Getzoff, E. D. & Stuehr, D. J. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 6260–6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh, D. K., Wu, C. Q., Pitters, E., Moloney, M., Werner, E. R., Mayer, B. & Stuehr, D. J. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 10609–10619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph, D. R. & Muench, K. H. (1971) J. Biol. Chem. 246, 7602–7609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lloyd, A. J., Thomann, H. U., Ibba, M. & Soll, D. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 2886–2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang, X., L, Otero, F. J., Skene, R. J., McRee, D. E., Schimmel, P. & de Pouplana, L. R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 15376–15380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mura, C., Katz, J. E., Clarke, S. G. & Eisenberg, D. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 326, 1559–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitabatake, M., Ali, K., Demain, A., Sakamoto, K., Yokoyama, S. & Soll, D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 23882–23887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sever, S., Rogers, K., Rogers, M. J., Carter, C. A. & Soll, D. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doublie, S., Bricogne, G., Gilmore, C. & Carter, C. W. (1995) Structure (London) 3, 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu, Y. D., Liu, Y. Q., Shen, N., Xu, X., Xu, F., Jia, J., Jin, Y. X., Arnold, E. & Ding, J. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8378–8388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Praetorius-Ibba, M., Stange-Thomann, N., Kitabatake, M., Ali, K., Soll, I., Carter, C. W., Ibba, M. & Soll, D. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 13136–13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Retailleau, P., Yin, Y., Hu, M., Roach, J., Bricogne, G., Vonrhein, C., Roversi, P., Blanc, E., Sweet, R. M. & Carter, C. W., Jr. (2001) Acta. Crystallogr. D 57, 1595–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Retailleau, P., Huang, X., Yin, Y. H., Hu, M., Weinreb, V., Vachette, P., Vonrhein, C., Bricogne, G., Roversi, P., Ilyin, V. & Carter, C. W. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 325, 39–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carnicelli, D., Brigotti, M., Rizzi, S., Keith, G. A., Montanaro, L. & Sperti, S. (2001) FEBS Lett. 492, 238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekine, S., Nureki, O, Dubois, D. Y., Bernier, S., Chenevert, R., Lapointe, J., Vassylyev, D. G. & Yokoyama, S. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 676–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nooren, I. M. A. & Thornton, J. M. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 3486–3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crane, B. R., Arvai, A. S., Gachhui, R., Wu, C., Ghosh, D. K., Getzoff, E. D., Stuehr, D. J. & Tainer, J. A. (1997) Science 278, 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Healy, F. G., Wach, M., Krasnoff, S. B., Gibson, D. M. & Loria, R. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 38, 794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bourassa, J. L., Ives, E. P., Marqueling, A. L., Shimanovich, R. & Groves, J. T. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 5142–5143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herold, S. (2004) Free Radical Biol. Med. 36, 565–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moller, J. K. S. & Skibsted, L. H. (2004) Chem.–Eur. J. 10, 2291–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicolis, S., Monzani, E., Roncone, R., Gianelli, L. & Casella, L. (2004) Chem.–Eur. J. 10, 2281–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunori, M. (2001) Trends. Biochem. Sci. 26, 209–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivanov, K. A., Moor, N. A. & Lavrik, O. I. (2000) Biochemistry (Mosc.) 65, 888–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ko, Y., Park, H. & Kim, S. (2002) Proteomics 2, 1304–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freist, W., Gauss, D. H., Soll, D. & Lapointe, J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 378, 1313–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roy, H., Becker, H. D., Reinbolt, J. & Kern, D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9837–9842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Min, B., Pelaschier, J. T., Graham, D. E., Tumbula-Hansen, D. & Soll, D. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2678–2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dubois, D. Y., Blaise, M., Becker, H. D., Campanacci, V., Keith, G., Giege, R., Cambillau, C., Lapointe, J. & Kern, D. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7530–7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campanacci, V., Dubois, D. Y., Becker, H. D., Kern, D., Spinelli, S., Valencia, C., Pagot, F., Salomoni, A., Grisel, S., Vincentelli, R., et al. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 337, 273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Battista, J. R. (1997) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51, 203–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu, Y. Q., Zhou, J. Z., Omelchenko, M. V., Beliaev, A. S., Venkateswaran, A., Stair, J., Wu, L. Y., Thompson, D. K., Xu, D., Rogozin, I. B., et al. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4191–4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, X. L., Schimmel, P. & Ewalt, K. L. (2004) Trends. Biochem. Sci. 29, 250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buddha, M. R., Tao, T., Parry, R. J., and Crane, B. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.