Abstract

Advances in the use of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes for heart regeneration and in vitro disease models demand a greater understanding of how these cells grow and mature in 3-dimensional space. In this study, we developed an analysis methodology of single cardiomyocytes plated on 2D surfaces to assess their 3D myofilament volume and its z-height distribution, or shape, upon hypertrophic stimulation via phenylephrine (PE) treatment or long-term culture (“aging”). Cardiomyocytes were fixed and labeled with α-actinin for confocal microscopy imaging to obtain z-stacks for 3D myofilament volume analysis. In primary neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs), area increased 72% with PE, while volume increased 31%. In hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, area increased 70% with PE and 4-fold with aging; however, volume increased significantly only with aging by 2.3-fold. Analysis of z-height myofilament volume distribution in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes revealed a shift from a fairly uniform distribution in control cells to a basally located volume in a more flat and spread morphology with PE and even more so with aging, a shape that was akin to all NRVMs analyzed. These results suggest that 2D area is not a sufficient measure of hiPSC-cardiomyocyte growth and maturation, and that changes in 3D volume and its distribution are essential for understanding hiPSC-cardiomyocyte biology for disease modeling and regenerative medicine applications.

Keywords: Confocal microscopy, Image analysis, Phenylephrine, Aging, Myofilament volume

Introduction

Heart disease is the leading global cause of death and is frequently due, at least in part, to native cardiomyocytes’ extremely limited capacity for proliferation.19,31 Fortunately, many advances in the generation and use of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes for myocardial regeneration have been made,6,16,33 and implanting engineered cardiac tissue to improve heart function is becoming a possibility.22,30 However, a more complete understanding of how hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, the building blocks of these tissues, grow and mature is necessary to optimize their performance in engineered tissues and other regenerative therapies to increase efficacy in pre-clinical and clinical applications.

To date, most studies characterize the morphology of hiPSC-cardiomyocytes and other primary cardiomyocytes from two dimensional (2D) images, analyzing parameters including area, elongation, and perimeter.1,12,17,23 However, cells are inherently 3-dimensional, even when plated on 2D substrates. We hypothesize that this height or z-component changes with cellular phenotype, affects total cell volume, and is therefore a critical component to assess in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes as we study their maturation. Several methods of measuring cell volume have been reported, including the use of suspended microchannel resonators, non-interferometric quantitative phase microscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging of cardiac tissue.3,7,20 However, these techniques can be prohibitively complex, preventing their adoption beyond the labs in which they were produced. Developing a robust and widely accessible tool to analyze single cells in 3D is crucial to fully understanding how hiPSC-cardiomyocytes grow, mature, and respond to stimuli.

In this study, we develop a semi-automated, increased throughput image analysis protocol to quantify cell volume and shape using confocal microscopy z-stack imaging, CellProfiler,5 and MATLAB®. We successfully measure the myofilament volume of monodispersed neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) plated on glass in order to validate our protocol and subsequently demonstrate the sensitivity of the analysis by quantifying hypertrophy of NRVMs and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes in response to adrenergic stimulation by phenylephrine (PE) or hypertrophic stimulation by aging. Our results indicate that in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes 2D area is not an accurate predictor of 3D myofilament volume and that the z-height distribution of myofilament volume is sensitive to hypertrophic stimulation. Specifically, control (unstimulated) hiPSC-cardiomyocytes (~3 weeks old) were tall and round, and PE stimulation or aging induced a more flat 3D shape that resembles the shape of both control and stimulated NRVMs. Because these differences in hiPSC-cardiomyocyte morphology were only detected with careful analysis of 3D shape, it is critical to adopt robust volume analysis techniques in order to accurately describe cellular morphological behavior.

Methods

Cell Culture and Hypertrophic Stimulation

All hiPSC-cardiomyocytes were derived from the Gibco® Human Episomal iPSC Line (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), following a previously reported protocol.4 HiPSCs were maintained in chemically defined conditions on plates coated with truncated human vitronectin (VTN-N) in Essential 8™ medium (Life Technologies). For differentiation, hiPSCs were plated as colonies at a low density on truncated VTN-N-coated 6-well plates in Essential 8™ Medium. HiPSCs were grown to 80% confluency at which point chemically defined directed differentiation was performed in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 213 μg/mL l-Ascorbic Acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 500 μg/mL human serum albumin (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA) (CDM3)4 with the sequential application of CHIR 99021 (6 µM, d0–d1) followed by inhibitor of Wnt protein 2 (IWP2, 5 µM, d3–d5; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After 2 to 3 weeks of differentiation, hiPSC-CMs were harvested using 0.25% Trypsin (Life Technologies) and dispersed into single cells via trituration. HiPSC-cardiomyocytes were replated on Matrigel-coated, #1.5 glass coverslips at approximately 26,000 cells/cm2. Aged hiPSC-cardiomyocytes were cultured for 12 months before being trypsinized and replated. Aged cells were cultured for 6 days before staining and imaging to correspond with replating time of PE-treated cells.

Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were a generous gift from Dr. Ulrike Mende (Cardiovascular Research Center, Rhode Island Hospital) and were harvested in accordance with all institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. NRVMs and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes were given 72 h to adhere and recover after replating and before beginning stimulation by phenylephrine (PE). Cells received either PE (2 µM) with Timolol (to ensure α-adrenergic stimulation, 0.2 µM)33 or media alone for 72 h. For cytosolic volume experiments, hiPSC-cardiomyocytes were incubated with Alexa Fluor® conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, 10 µg/mL, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min prior to fixation. All cells were then rinsed with KCl (100 mM) to induce diastole and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4 °C. Cells were stored in DPBS at 4 °C until stained.

Immunocytochemistry and Imaging

Cells were blocked in 1.5% normal goat serum (NGS; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) and stained for α-actinin (Mouse monoclonal α-actinin, 1:800 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich) in 1.5% NGS overnight followed by 1 h incubation at room temperature with Alexa Fluor® 594 Goat anti-Mouse as the secondary antibody (Life Technologies). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI, and the coverslips were inverted onto slides using VectaShield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Confocal microscopy (Zeiss 510 Meta Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope) was performed using a 63.3× oil immersion objective and z-stacks (0.43 µm thick optical sections) of single cells from each experimental condition (n ≥ 53) were obtained.

Image Analysis

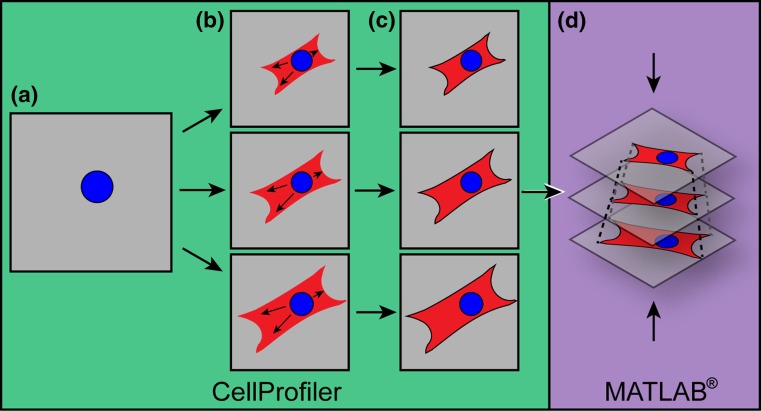

Collected images were processed in ImageJ25 and analyzed with a custom pipeline in CellProfiler.1 In brief, cell nuclei were identified from the compressed z-stack image of the channel recording DAPI (Fig. 1a). The cell body was identified in each slice of the z-stack using a combination of propagation from the identified nucleus and fluorescence intensity of the stained myofibrils (Fig. 1b and 1c). Measurements of cell body area were made in CellProfiler. Two-dimensional area for each cell was defined as the largest slice of its z-stack, as this value was not significantly different from compressed z-stack area and more closely represents cellular cross-sectional area. The maximum cross-sectional area was used to quantify 2D effects of hypertrophic stimulation (Fig. 2) and for normalization of volume distribution by slice area in individual cells (Figs. 4c–4f). Binning of volume distribution was performed by dividing the number of slices within a stack by 5 and averaging the parameter of interest within each section from z = 0, defined as the cell-substrate interface, to z = 1, defined as the top of the cell (Fig. 4b).

Figure 1.

Automated image analysis compiles z-stack images to calculate cardiomyocyte volume. (a) The nucleus is identified from a compressed z-stack; (b) The nucleus mask is imposed on each slice of the α-actinin stained cell’s z-stack images, and the propagation function is used to couple cell area within each slice with the nucleus; (c) Cell borders are drawn for cardiomyocyte area in each slice and measurements of the identified cell area is made for each slice in CellProfiler; (d) Measurement data is exported to MATLAB® where z-stack slices are reconstructed into 3D cardiomyocytes. See “Methods” for details.

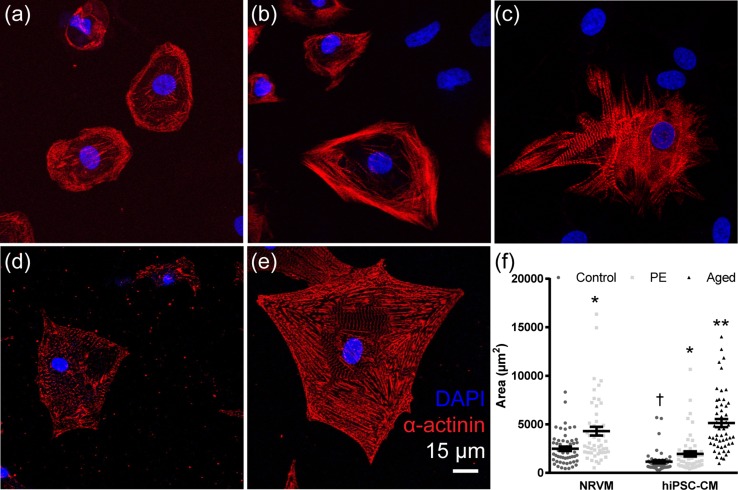

Figure 2.

Cardiomyocyte 2D phenotype and area changes in hypertrophic stimulation. Single hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) were seeded in control conditions (a) stimulated with phenylephrine (PE; b) and aged for 12 months (c). Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were seeded in control conditions (d) and stimulated with PE (e) Cardiomyocytes were stained for α-Actinin (red) and nuclei (blue). Scale bar: 15 µm. (f) Cell area was calculated for NRVM control and PE and hiPSC-CM control, PE, and aged groups (n = 53 per group); bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.01 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. NRVM control.

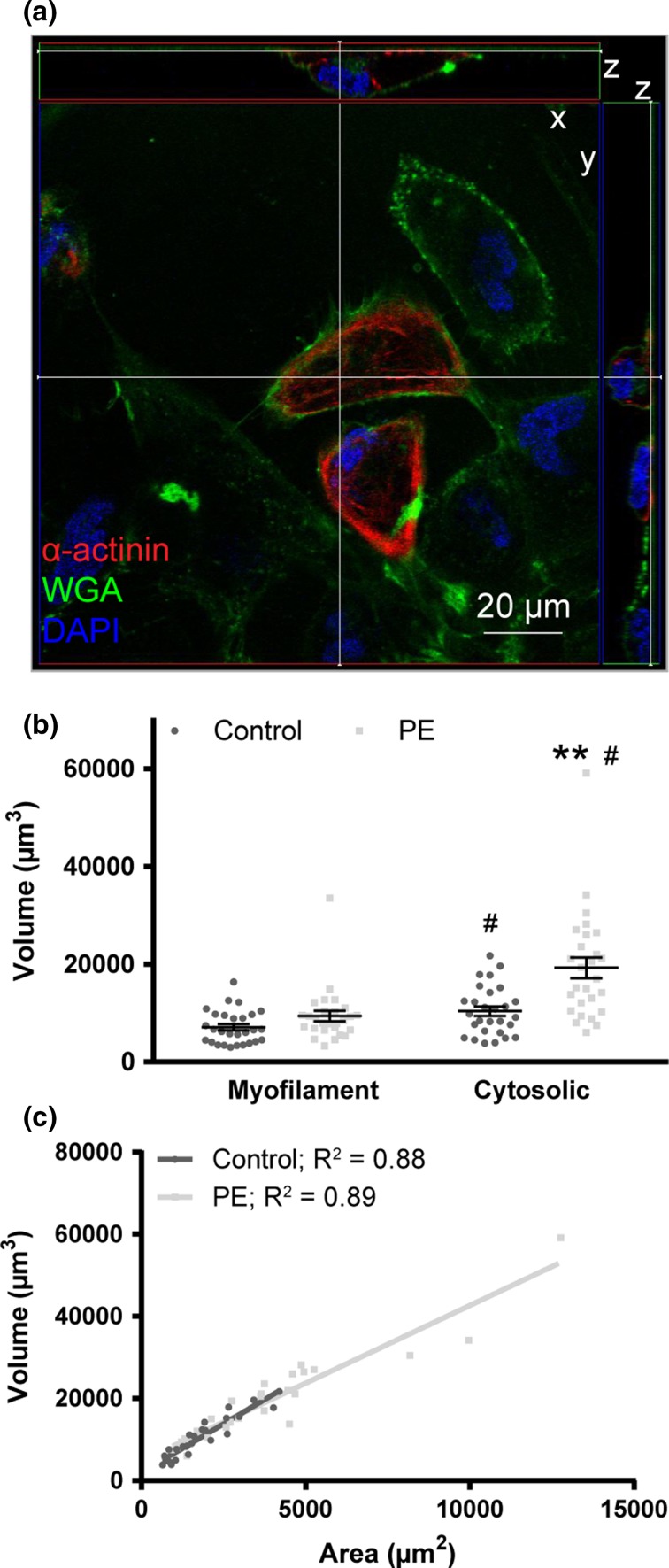

Figure 4.

Cytosolic volume responds to hypertrophic stimulation in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes. (a) HiPSC-cardiomyocytes stained for α-actinin (red), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, green), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in orthoslice view. (b) HiPSC-cardiomyocyte myofilament and cytosolic volume determined by α-actinin and WGA staining, respectively, for control and PE-stimulated conditions. Bars represent mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01 vs. control of same volume type; # P < 0.01 vs. myofilament volume of same treatment. (c) The correlation between area and cytosolic volume was plotted for hiPSC-cardiomyocytes with R 2 values displayed next to treatment group.

Because the thickness (z height) between each z-stack slice was more than 10-fold less than the height of the cell, the volume was calculated as a trapezoidal prism, where N is the number of slices in the z-stack (Eq. 1).

| 1 |

MATLAB® (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) code was implemented to calculate cell volume from the output CellProfiler area (Fig. 1d). Total cell height was calculated as the distance between the first slice with α-actinin or DAPI labeling at the cell-substrate interface and the last slice with α-actinin or DAPI labeling at the top of the cell (Fig. 4a). CellProfiler and MATLAB codes are available for free download from the Brown Digital Repository, doi:10.7301/Z0WS8R5F.

Statistical Analysis

Each hypertrophy stimulation experiment was performed in triplicate with cells from independent cell isolations (NRVMs) or differentiation runs (hiPSC-cardiomyocytes). Data are presented as the average across all cell isolations or differentiation runs, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Intra- and inter-species comparisons were made with ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, and the volume-area relationship was characterized with linear regression. Comparison of myofilament and cytosolic volume measurements was made with paired Student’s t test. Significance for all analyses was determined as P < 0.05. All data analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Hypertrophic Stimulation Increases Cardiomyocyte Area

To begin morphological assessment of cardiomyocytes, we characterized the hypertrophic response of monodisperse, plated neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes to adrenergic stimulation with phenylephrine (PE) using two-dimensional area measurements. PE stimulates hypertrophy in rodent cardiomyocytes32 and hESC-cardiomyocytes,8,11 thus we hypothesized that cell area would increase in both PE-stimulated NRVMs and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes. To test this, cardiomyocytes were treated for 72 h with PE and continued to beat spontaneously.

In addition to undergoing hypertrophy with PE stimulation, cardiomyocytes hypertrophy during development (Engelmann, Vitullo, and Gerrity). In order to assess if cardiomyocyte growth occurred during in vitro long-term culture, hiPSC-cardiomyocytes were cultured for 12 months, during which time they maintained their automaticity, and were then replated for single-cell analysis. Aged cardiomyocytes had morphological signs of hypertrophy with a 4.5-fold increase in area, a 3.0-fold increase in perimeter, a 33 ± 14% increase in nuclear area (potentially due to increased nuclear ploidy,2 and a 21 ± 5% increase in sarcomere length (P < 0.05, n = 20 cells per group). This morphological hypertrophy with aging has been reported to coincide with more mature electromechanical properties of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes.17

Cardiomyocytes stained for α-actinin, a protein of the myofibril z-disks, showed striations throughout the cell in both hiPSC-cardiomyocytes (Figs. 2a–2c) and NRVMs (Figs. 2d–2e). PE treatment significantly increased area in NRVMs by 72% from 2492 ± 228 to 4299 ± 455 µm2 and in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes by 70% from 1148 ± 149 to 1950 ± 802 µm2 (Fig. 2f; n = 53 per group, P < 0.05). Aged hiPSC-cardiomyocytes showed a 3.5-fold increase in area over control with an area of 5139 ± 421 µm2 (n = 53, P < 0.01). NRVMs had a significantly greater area than hiPSC-cardiomyocytes of the corresponding treatment group (P < 0.05). Area determined by membrane labeling in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes yielded similar results, where PE stimulation induced a 2-fold increase in area (n = 27 cells per group, P < 0.01). These results confirmed that PE elicited a hypertrophic response in 2D area for both NRVMs and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes and that aged hiPSC-cardiomyocytes underwent hypertrophy during 12 months of culture.

Myofilament Volume Increases in Aged hiPSC-Cardiomyocytes

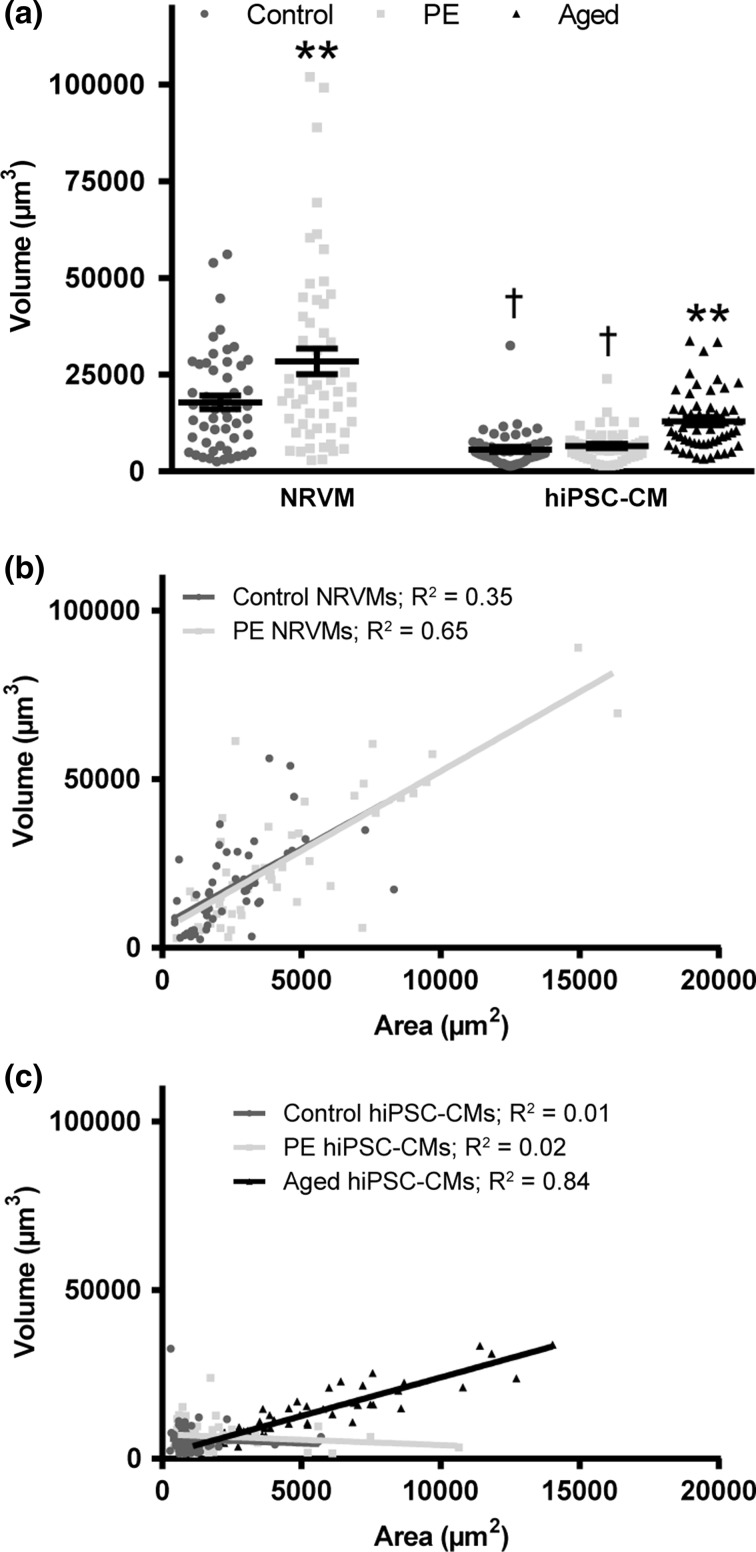

We next sought to determine if PE stimulation significantly increased cardiomyocyte volume. To accomplish this, a custom CellProfiler pipeline and MATLAB® code were written which reconstructed cardiomyocytes from confocal z-stacks to determine volume (Fig. 3a). NRVM volume increased significantly with PE stimulation by 31% from 17,892 ± 1752 to 28,446 ± 3274 µm3 (n = 53 cells per group; P < 0.01). HiPSC-cardiomyocyte volume, however, increased only slightly from 5673 ± 651 to 6583 ± 555 µm3 and did not reach significance (n = 53 cells per group, P = 0.3). Analysis of biological replicates revealed no significant difference in volume with PE stimulation among single differentiation runs. Hypertrophy of aged cardiomyocytes, however, resulted in a significant volume increase of 2.3-fold over control to 12,962 ± 1050 µm3 (n = 53 cells, P < 0.01). These results suggest that cell area does not accurately predict cell volume of hiPSC-cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3.

Volume correlates differentially with cardiomyocyte source and hypertrophic stimulation. (a) Neonatal rat ventricular myocyte (NRVM) and hiPSC-cardiomyocyte (hiPSC-CM) volume was determined under phenylephrine stimulation (PE) and aging (Aged). Bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. control of same species; **P < 0.01 vs. control of same species; †P < 0.05 vs. NRVM control. (b,c) The correlation between area and volume was plotted for NRVMs (b) and hiPSC-CMs (c) with R 2 values displayed next to each group.

Correlation of cell volume to cell area was performed in order to quantify the predictive value of area. Control and PE-stimulated NRVMs and aged hiPSC-cardiomyocytes were strongly correlated (R 2 = 0.35–0.83, Fig. 3b) compared to control and PE-stimulated hiPSC-cardiomyocytes (R 2 = 0.01–0.02) (Fig. 3c). Results in NRVM correlation were similar to those previously reported.24 Cardiomyocyte cytosolic volume was analyzed for control and PE-stimulated hiPSC-cardiomyocytes using the membrane marker wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; Fig. 4a). Cytosolic volume was significantly greater than myofilament volume for both control and PE-stimulated cells (n = 27 cells per group, P < 0.01), and only cytosolic, not myofilament volume, increased significantly with PE treatment (P < 0.01; Fig. 4b). Additionally, the relationship between area and volume determined by WGA labeling was strongly correlated (R 2 = 0.88–0.89; Fig. 4c). These results suggest that cytosolic volume changes independently of myofilament volume during PE stimulation. Because we are interested in using this cell type in a regenerative context as a contractile cell, myofibril volume (the amount of contractile lattice per cell) is the functionally relevant morphological metric of interest. Additionally, myofilament markers are widely used in the literature to quantify cardiomyocyte morphology.1,10,27 Thus, further studies of cardiomyocyte morphology were explored with myofilament quantification where we investigated morphological reasons why a significant increase in myofilament area was not accompanied by an increase in myofilament volume with PE stimulation.

Hypertrophic Stimulation Changes hiPSC-Cardiomyocyte 3D Shape

Because 3D myofilament volume and 2D area were not correlated for control and PE-treated hiPSC-cardiomyocytes (unlike NRVMs), we hypothesized that the 3D morphology of hiPSC-cardiomyocytes differed with and without PE stimulation. Cell height was first examined to determine how cells changed total height in the z-direction with hypertrophic stimulation (Fig. 5b). No significant difference was observed in control and PE-treated NRVMs (8.23 ± 0.22 and 8.58 ± 0.19 µm, respectively); however, hypertrophic stimulation in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes with PE (9.49 ± 0.42 µm) or aging (6.35 ± 0.26 µm) led to a significantly decreased cell height compared to control (11.41 ± 0.45 µm, P < 0.01).

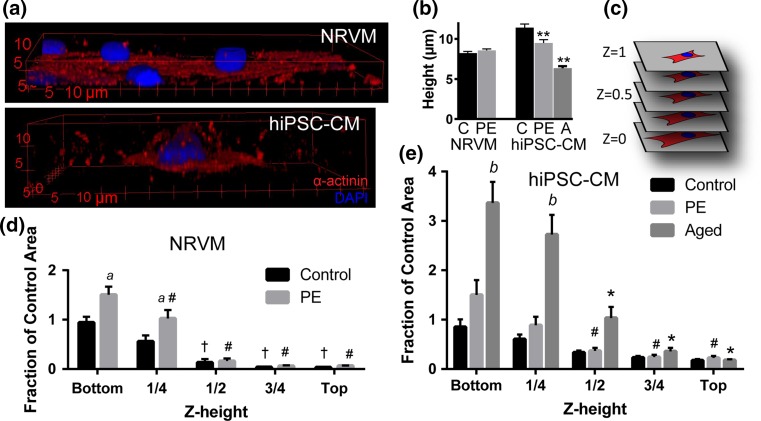

Figure 5.

Volume and z-height distribution in hypertrophically stimulated cardiomyocytes. (a) Representative 3D renderings of control neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs, top) and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CM, bottom) stained for α-actinin (red) and nuclei (blue). (b) Average height of NRVMs and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes under control (C), phenylephrine stimulation (PE) and aging (A) conditions. **P < 0.01 vs. control of same species. (c) Schematic for z-height convention. (d,e) Fraction of control maximum area as a function of z-height in NRVMs (d) and hiPSC-CMs (e). Note that the y-axis has the same linear scale (unit/inch) for direct comparison. † P < 0.05 vs. z = 0 within control; # P < 0.05 vs. z = 0 within PE; *P < 0.05 vs. z = 0 within Aged; a P < 0.05 for PE vs. control at same z-height; b P < 0.05 for Aged vs. control at same z-height. Bars represent mean ± SEM.

To further investigate how cell shape changed in three dimensions, we analyzed the volume distribution in ten representative cells of each group. For each image slice of the z-stack (with z = 0 corresponding to the cell-substrate interface and z = 1 to the top of the cell, Fig. 5c), cell area was normalized to the average maximum area of the control group of the same cell type and areas were binned by z-height for graphical representation. In NRVMs, distribution of cellular volume was similar in control and PE-stimulated cells, with significantly smaller areas in the top half of the cell compared to the bottom in both groups (P < 0.05, Fig. 5d). The ~50% increase in area at z = 0 and 0.25 height with PE treatment reflects our 2D area measurements and is not present at z ≥ 0.5. This significant increase in area for z < 0.5 with PE treatment indicates that the volume increase measured with PE treatment is occurring in the bottom half of the cells. In hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, only PE-treated and aged groups showed significantly decreased area in the top half of the cells (P < 0.05, Fig. 5e), demonstrating a more uniform distribution of cell volume throughout the height of the cell in control hiPSC-cardiomyocytes.

These data suggest that hypertrophic stimulation via PE and aging causes a significant shift in hiPSC-cardiomyocyte myofilament volume distribution, concentrating it in the bottom half of the cell. In contrast, PE treatment in NRVMs causes only slight redistribution of myofilament volume since volume is already concentrated in the bottom half of control NRVMs. Additionally, whereas PE treatment led to a significant increase in area in the bottom half of the cell (z < 0.5) over control in NRVMs (a, P < 0.05 vs. control at same z-height, Fig. 5d), PE treatment in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes did not significantly increase area at z < 0.5 contrary to 2D area measurements (Fig. 5e). This discrepancy may be due to the use of binning for analysis of 3D volume distribution and the fact that maximum slice area (used for normalization) was not always at z = 0 (shown as a slightly less than 1.0 value for control hiPSC-cardiomyocyte area at z = 0). This data analysis underscores the need for carefully defined metrics in 2D and 3D and suggests that a more complete picture of cellular morphology can be obtained with both area and volumetric analysis. Interestingly, aged hiPSC-cardiomyocytes displayed a significant increase in area at z < 0.5 vs. control (b, P < 0.05 vs. control, Fig. 5e), showing a > 3-fold increase in area at z = 0. Further, aged hiPSC-cardiomyocyte area was significantly reduced and not different from control at z ≥ 0.5 (Fig. 5e), similar to control NRVMs. However, all hiPSC-cardiomyocytes maintained ~10% area at z > 0.5 suggesting a fundamental difference vs. NRVMs. Taken together, these data suggest that while PE treatment leads to an increase in myofilament volume in NRVMs, it leads only to a redistribution of myofilament volume in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes and that hypertrophy (defined as an increase in cell volume) can be achieved with aging hiPSC-cardiomyocytes in culture.

Discussion

In this study, a new image analysis protocol was developed to analyze 3D morphology of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes. The protocol was then used to examine the effects of hypertrophic stimulation on cardiomyocyte shape in 3D. We demonstrate that (1) aging increases 2D area in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes and phenylephrine (PE) stimulation increases 2D area in both NRVMs and hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, (2) our image analysis protocol can be successfully implemented to quantify 3D morphology of single cells from confocal z-stack images, (3) PE stimulation increases myofilament volume in NRVMs but not hiPSC-cardiomyocytes while aging increases myofilament volume in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, and (4) the discrepancy in area vs. volume quantification with PE stimulation in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes can be explained by differences in 3D morphology.

Our results provide a novel explanation for differing reports of hypertrophic response to phenylephrine stimulation in the literature. NRVMs are consistently observed to hypertrophy with phenylephrine stimulation, however, contradictory results have been reported for hiPSC-cardiomyocytes.11,27 Using the image analysis method described in this study, we characterized three-dimensional volume and its distribution (or shape) and demonstrated an important difference between single NRVM and hiPSC-cardiomyocyte shape under control growth conditions. While untreated NRVMs are spread and undergo more spreading during phenylephrine stimulation, untreated hiPSC-cardiomyocytes present a taller, more variable, and rounded morphology and become more flat and spread upon phenylephrine stimulation. This change in overall hiPSC-cardiomyocyte shape may account for why a significant increase in area is not accompanied by a corresponding increase in myofilament volume during PE stimulation in our study. Implementing this rigorous three-dimensional characterization in other systems may elucidate changes in cell shape which could underlie apparently conflicting responses of cells to growth stimuli.

This data also describes for the first time how hiPSC-cardiomyocyte shape changes with hypertrophic stimulation via aging. Metabolic14 and functional4,15 maturation have been demonstrated in aged pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, however, a change in three-dimensional shape has not been described. Cardiomyocytes increase in volume during fetal development,29 and this study demonstrates that the same phenomena occurs in long-term in vitro culture of hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, with volume increasing more than 2-fold in aged 12-month-old cardiomyocytes vs. 2-week-old control cells. It should be noted that while differences in hiPSC-cardiomyocyte volume and shape were observed with pathological (phenylephrine) and physiological (aging) hypertrophy, this protocol is a means to characterize those differences rather than a tool to identify pathological vs. physiological mechanisms of hypertrophy. The findings presented here, where hiPSC-cardiomyocyte volume increased from 5673 µm3 at 2 weeks old to 12,962 µm3 over 1 year of culture, is consistent with the limited data available for primary human cardiomyocytes, where volume was reported to be 5835 µm3 at birth.18

PE-stimulated growth of hiPSC-cardiomyocytes differs markedly from aging in long-term culture in our study, suggesting mechanistic differences in these two stimuli. With PE stimulation, we observed a redistribution of myofilaments, localizing at the cell-substrate interface and resulting in increased cell area without a corresponding increase in myofilament volume. This could be explained via PE-mediated changes in focal adhesion expression28 that may initiate myofibril localization to the sub-sarcolemma compartment through changes in the cytoskeleton as shown in development.21 The short duration of PE stimulation and culture may preclude new myofibril formation in young hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, even though we observed an increase in cell volume using a membrane label (Fig. 4). A similar increase in cardiomyocyte size (measured by surface area) without accompanying change in myofibril content has been observed in NRVMs stimulated for just 36 h.26 Taken together, these data suggest that acute (72-h) PE stimulation of hiPSC-cardiomyocytes may progress through the same phases with slower kinetics, resulting in an increased cytosolic volume, focal adhesion mediated redistribution of myofilaments, and no increase in myofilament volume. In contrast, we observed both increased area and volume in aged hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, which may be attributed to alternative mechanisms of growth. Aged hiPSC-cardiomyocytes likely have more focal adhesions, similar to the approximately threefold increase in vinculin protein expression in 24-month-old vs. 6-month-old rat ventricles.13 Further, in aged hiPSC-cardiomyocytes, myofibril formation likely occurs during long-term culture, reflected in a 2.3-fold increase in myofilament volume, a phenomenon well documented in cardiomyocytes undergoing early development where human cardiomyocyte volume increases approximately 4-fold in the first 3 months after birth.18 Thus, additional study of the stimulation dependence and kinetics of myofibril assembly, re-organization, and relationship to transmembrane adhesions and the sarcolemma in hiPSC-cardiomyocytes will be a valuable area to pursue.

The analysis protocol described here has valuable uses for characterizing changes in cell shape over time, beyond models of hypertrophic stimulation. Cells are known to respond to and remodel the environment with which they are presented, and their three-dimensional shape may change due to this process. Further development of this image analysis protocol could elucidate how single cardiomyocytes interact with matrices in three dimensions, and future work will seek to adapt this protocol to more complex three-dimensional environments such as those found in engineered tissues.

In summary, we have developed a sensitive image acquisition and analysis protocol to characterize three-dimensional size and shape of single cells and demonstrated its ability to detect hypertrophy of hiPSC-cardiomyocytes. This protocol is easily adaptable across cell types and laboratories. As tissue engineering continues to develop in three-dimensional space, analysis methods must be created and adopted to mirror this, and the protocol reported here takes an important first step in providing higher throughput 3D analysis for single cells. It will be necessary to continue to push these analyses protocols toward characterizing dense, cellular 3D tissues in order to accurately understand these complex environments and cellular responses to them.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Celinda Kofron, Ph.D. for sharing NRVMs for this study and funding from NIH R00 HL115123 (to K.L.K.C.), the Brown University Eccleston Fellowship (C.E.R.), and a Brown University Karen T. Romer Undergraduate Teaching and Research Award (H.H.C.).

Conflict of Interest

Authors Rupert, Chang, and Coulombe declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statements of Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All studies on neonatal rat ventricular myocytes were performed with cells provided by Dr. Ulrike Mende’s laboratory at the Rhode Island Hospital Cardiovascular Research Center, in accordance with all institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. No human research was conducted by the authors in this study.

References

- 1.Bass GT, et al. Automated image analysis identifies signaling pathways regulating distinct signatures of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012;52(5):923–930. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann O, et al. Identification of cardiomyocyte nuclei and assessment of ploidy for the analysis of cell turnover. Exp. Cell Res. 2011;317(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan AK, et al. Measuring single cell mass, volume, and density with dual suspended microchannel resonators. Lab Chip. 2014;14(3):569–576. doi: 10.1039/C3LC51022K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burridge PW, et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Methods. 2014;11(8):855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter AE, et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 2006;7(10):R100. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chong JJH, et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510(7504):273–277. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coelho-Filho OR, et al. Quantification of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by cardiac magnetic resonance: implications for early cardiac remodeling. Circulation. 2013;128(11):1225–1233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dambrot C, et al. Serum supplemented culture medium masks hypertrophic phenotypes in human pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014;18(8):1509–1518. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelmann GL, Vitullo JC, Gerrity RG. Morphometric analysis of cardiac hypertrophy during development, maturation, and senescence in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ. Res. 1987;60(4):487–494. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.60.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Földes G, et al. Modulation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte growth: a testbed for studying human cardiac hypertrophy? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011;50(2):367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Földes G, et al. Aberrant α-adrenergic hypertrophic response in cardiomyocytes from human induced pluripotent cells. Stem Cell. Rep. 2014;3(5):905–914. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hazeltine LB, et al. Effects of substrate mechanics on contractility of cardiomyocytes generated from human pluripotent stem cells. Int. J. Cell. Biol. 2012;2012:508294. doi: 10.1155/2012/508294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaushik G, et al. Vinculin network-mediated cytoskeletal remodeling regulates contractile function in the aging heart. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7(292):292ra99. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreipke R, et al. Metabolic remodeling in early development and cardiomyocyte maturation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016;52:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lian X, Hsiao C, et al. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(27):E1848–E1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lian X, Zhang J, et al. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8(1):162–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundy SD, et al. Structural and functional maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(14):1991–2002. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mollova M, Bersell K, Walsh S, Savla J, Das LT, Park S-Y, Silberstein LE, et al. Cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to heart growth in young humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2013;110(4):1446–1451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214608110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasumarthi KBS. Cardiomyocyte cell cycle regulation. Circ. Res. 2002;90(10):1044–1054. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000020201.44772.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips KG, et al. Optical quantification of cellular mass, volume, and density of circulating tumor cells identified in an ovarian cancer patient. Front. Oncol. 2012;2:72. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raeker MÖ, et al. Membrane-myofibril cross-talk in myofibrillogenesis and in muscular dystrophy pathogenesis: lessons from the zebrafish. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:14. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riegler J, et al. Human engineered heart muscles engraft and survive long term in a rodent myocardial infarction model. Circ. Res. 2015;117(8):720–730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez ML, et al. Measuring the contractile forces of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes with arrays of microposts. J. Biomech. Eng. 2014;136(5):051005. doi: 10.1115/1.4027145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryall KA, Jeffrey JS. Automated imaging reveals a concentration dependent delay in reversibility of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012;53(2):282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH image to imagej: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9(7):671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siddiqui RA, et al. Inhibition of phenylephrine-induced cardiac hypertrophy by Docosahexaenoic acid. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004;92(6):1141–1159. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka A, et al. Endothelin-1 induces myofibrillar disarray and contractile vector variability in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014;3(6):e001263. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor JM, Rovin JD, Parsons JT. A role for focal adhesion kinase in phenylephrine-induced hypertrophy of rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(25):19250–19257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909099199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thornburg K, et al. Regulation of the cardiomyocyte population in the developing heart. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011;106(1):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wendel JS, et al. Functional effects of a tissue-engineered cardiac patch from human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in a rat infarct model. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015;4(11):1324–1332. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO . The Top 10 Causes of Death. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia Y, et al. Inhibition of phenylephrine induced hypertrophy in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes by the mitochondrial KATP channel opener diazoxide. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2004;37(5):1063–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W, et al. Selective loss of fine tuning of Gq/11 signaling by RGS2 protein exacerbates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(9):5811–5820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]