Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: community-acquired infections/aetiology, HIV infections/complications, lung diseases/microbiology, prospective studies

Abstract

The study of the etiological agents of community-acquired pulmonary infections is important to guide empirical therapy, requires constant updating, and has a substantial impact on the prognosis of patients. The objective of this study is to determine prospectively the etiology of community-acquired pulmonary infections in hospitalized adults living with HIV. Patients were submitted to an extended microbiological investigation that included molecular methods. The microbiological findings were evaluated according to severity of the disease and pneumococcal vaccine status. Two hundred twenty-four patients underwent the extended microbiological investigation of whom 143 (64%) had an etiology determined. Among the 143 patients with a determined etiology, Pneumocystis jirovecii was the main agent, detected in 52 (36%) cases and followed by Mycobacterium tuberculosis accounting for 28 (20%) cases. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Rhinovirus were diagnosed in 22 (15%) cases each and influenza in 15 (10%) cases. Among atypical bacteria, Mycoplasma pneumoniae was responsible for 12 (8%) and Chlamydophila pneumoniae for 7 (5%) cases. Mixed infections occurred in 48 cases (34%). S pneumoniae was associated with higher severity scores and not associated with vaccine status. By using extended diagnostics, a microbiological agent could be determined in the majority of patients living with HIV affected by community-acquired pulmonary infections. Our findings can guide clinicians in the choice of empirical therapy for hospitalized pulmonary disease.

1. Introduction

Pneumonia is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in people living with the human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV). Its incidence has decreased after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), but these patients still have a higher risk of acquiring this type of infection than the general population and have higher mortality rates.[1]

The epidemiology of HIV-associated pulmonary disease is complex and influenced by various factors, notably the regional prevalence of pathogens, such as tuberculosis, and the accessibility to health care, mainly the access to effective antiretroviral therapy and antimicrobial prophylaxis.[2]

The study of the etiological agents of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is important to guide empirical therapy, requires constant updating, and has a substantial impact on the prognosis of patients.[3] However, few studies have systematically investigated the etiology of pneumonia in PLHIV and there is no consensus on a diagnostic algorithm for these patients.[4]

A recently studied algorithm among non-HIV patients showed that, by supplementing traditional diagnostic methods with new polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods, a high microbial yield is achieved among adults admitted to a general hospital due to CAP. This study also showed that mixed infections are frequent in this setting.[5]

The main purpose of this study was to determine prospectively the etiology of community-acquired pulmonary infections in hospitalized adults living with HIV. This study also aimed to analyze the contribution of different diagnostic methods, including those PCR-based, as well of the impact of different approaches to microbiological evaluation and to evaluate the microbiological findings in relation to the CD4+ T-cell count, the severity of disease, and pneumococcal vaccine status.

2. Methods

This is a subanalysis of a clinical trial that evaluated the treatment of CAP in 228 patients with HIV (Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry: RBR-8wtq2b) carried out at “Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas,” a tertiary teaching infectious diseases hospital in São Paulo, Brazil.

The eligibility criteria for participants were: patients 18 years of age or older with clinically and radiologically suspected CAP (cough and dyspnea or chest pain or sputum production and lung opacity detected by a radiologic method) who required antibiotic treatment (denoting a clinical diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia) and hospitalization, as decided by the attending physician.

Patients were excluded if they fulfilled the following criteria: risk factors for healthcare-associated pneumonia as defined by the American Thoracic Society,[6] an etiology established prior to admission that justified all the symptoms, previously included, pregnancy, or breastfeeding (based on the exclusion criteria of the clinical trial).

All patients provided written informed consent. The study occurred from September 2012 through July 2014 and was approved by the Institutional Committee of Ethics in Research (number 17/11).

Data collected on admission included demographic, clinical characteristics, and pneumococcal vaccine status as reported by the patient. HIV viral load and CD4+ T-cell count were registered if collected within 3 months before admission or during hospitalization.

Severity was evaluated using 2 scoring systems: pneumonia severity index (PSI)[7] and CURB-65,[8] as recommended by the American and British Thoracic Societies, respectively. The scores are able to stratify patients according to their risk of mortality. PSI is based on clinical, laboratory, and radiologic criteria, while CURB-65 is remarkable due to its simplicity, with only 5 criteria.

Our Institute's CAP protocol states that all patients should have blood samples collected for bacterial (2 samples), fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Sputum should be collected for direct examination for Pneumocystis jirovecii and acid-alcohol-resistant bacilli and cultured for fungi and mycobacteria.

Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected as indicated by the attending physician and tested for influenza A viruses (including H1N1) by PCR. Pleural effusion, tracheobronchial aspirates, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and biopsies were collected if clinically indicated.

For analytic purposes, this approach was considered the routine investigation. All patients in this study also had at their disposal a wider microbiological investigation, considered here as the extended investigation (the extended investigation also included the tests available in the routine investigation).

Blood samples were collected for serology for Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The first 50 patients had blood samples tested for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae by PCR.

For this study, sputum was also cultured for bacteria and urinary antigen test for Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 was performed.

Nonquantitative PCR methods were also used to investigate C pneumoniae, L pneumophila, M pneumoniae, P jirovecii, and adenovirus in respiratory samples. L pneumophila was only investigated in respiratory samples of the first 100 patients enrolled.

A 100 consecutive patients who had nasopharyngeal swabs available were tested by real time-PCR for the following agents: parainfluenza viruses 1 to 3, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses A and B, human coronaviruses CoV NL63, HKU1, OC43, and 229E, enterovirus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, bocavirus, human metapneumovirus, C pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis, and M pneumoniae.[9]

Due to operational reasons, including difficulties in obtaining biological samples and scarcity of tests, not all the available microbiological analyses were performed for every included patient.

The diagnostic criteria are outlined in the Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test, the level of significance was set at P = 0.05 (2-tailed). Analyses were performed using STATA 10.1.

3. Results

3.1. Enrolment

Two hundred twenty-eight patients were consecutively enrolled. Four patients were excluded after this stage: 1 withdrew consent, 1 had no pneumonia (mistaken inclusion), 1 revealed an exclusion criterion after inclusion, and 1 had been previously included. Thus, 224 cases were included in the analyses.

3.2. Patients’ characteristics

The mean age of the 224 patients was 40.3 years, with a standard deviation of 11.6 years, 154 (69%) were males, comorbidities were referred by approximately one-third of the patients, wherein liver disease and hypertension were the 2 most frequent.

Approximately one-third of the patients who knew about their vaccination status referred antipneumococcal vaccination.

The majority of patients never used, abandoned or referred irregular use of HAART. The CD4+ T-cell count was available for 90% of the patients, whereas 73% of cases were under 200 cells/mm3.

Regarding severity of pneumonia, 63 (28%) patients had a CURB-65 score greater than 1 and 88 (39%) had PSI above 3.

The detailed baseline characteristics of the 224 patients are shown in the Supplementary Table 1.

3.3. Microbiological findings

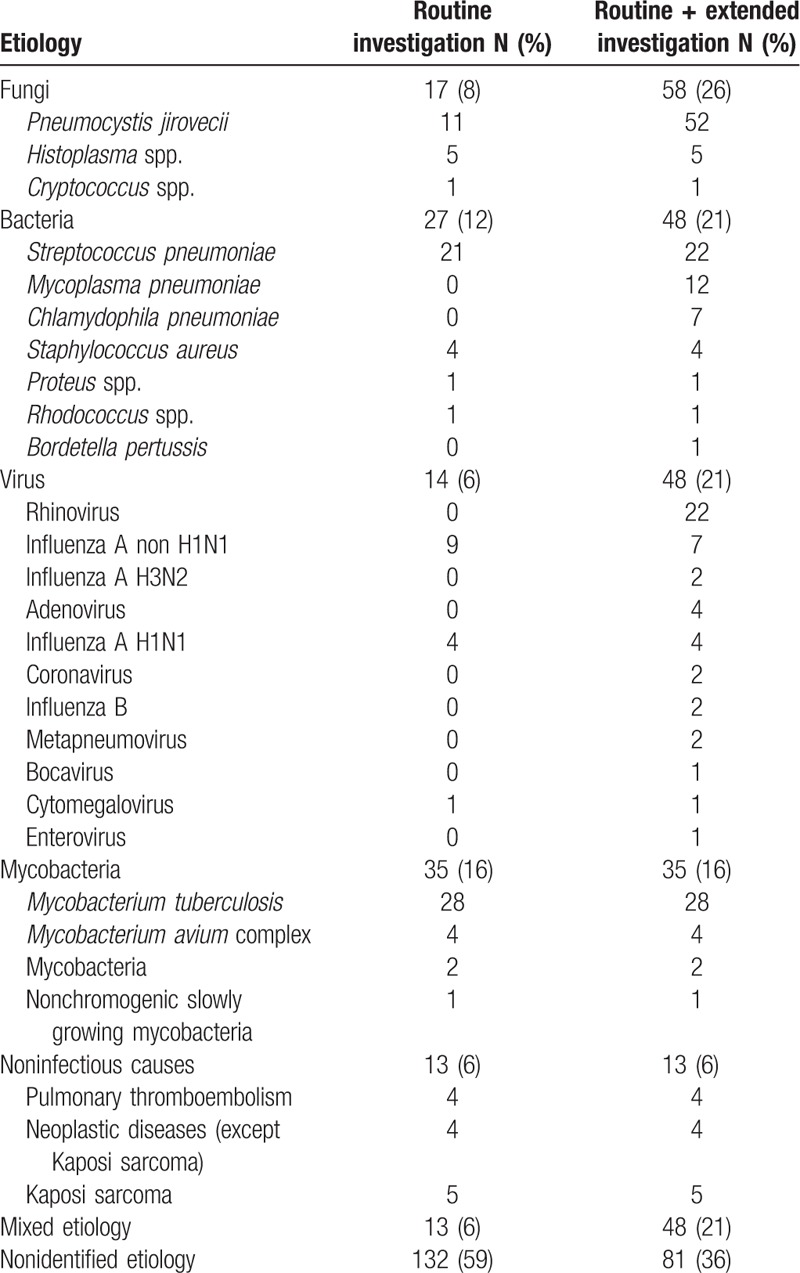

The microbiological routine investigation was able to determine the etiological agents in 92 (41%) patients (Table 1). Based on this investigation, the main etiological agent was Mycobacterium tuberculosis accounting for 28 cases (30% of those with an etiology determined); followed by S pneumoniae, with 21 (23%) cases; influenza, 13 (14%) cases; and P jirovecii, 11 (12%) cases.

Table 1.

Findings of microbiological investigation in 224 cases of community-acquired pulmonary infections in hospitalized patients living with HIV.

On the other hand, when including the extended microbiological investigation a microbiological agent was determined in 143 (64%) patients (Table 1). Among the 143 patients with microbiological findings, P jirovecii was the main agent, responsible for 52 (36%) cases. M tuberculosis was the cause of 28 (20%) cases, the same number as in the routine investigation. S pneumoniae and Rhinovirus were diagnosed in 22 (15%) cases each, followed by influenza in 15 (10%) cases. Atypical bacteria were also diagnosed: M pneumoniae was responsible for 12 (8%) and C pneumoniae for 7 (5%) cases.

Mixed etiology was found in a large proportion of cases (34%) by the extended microbiological investigation, the multiple combinations are detailed in the Supplementary Table 2 and the most frequent of which were: M pneumoniae + P jirovecii, P jirovecii + Rhinovirus, P jirovecii + M tuberculosis, and S pneumoniae + Rhinovirus.

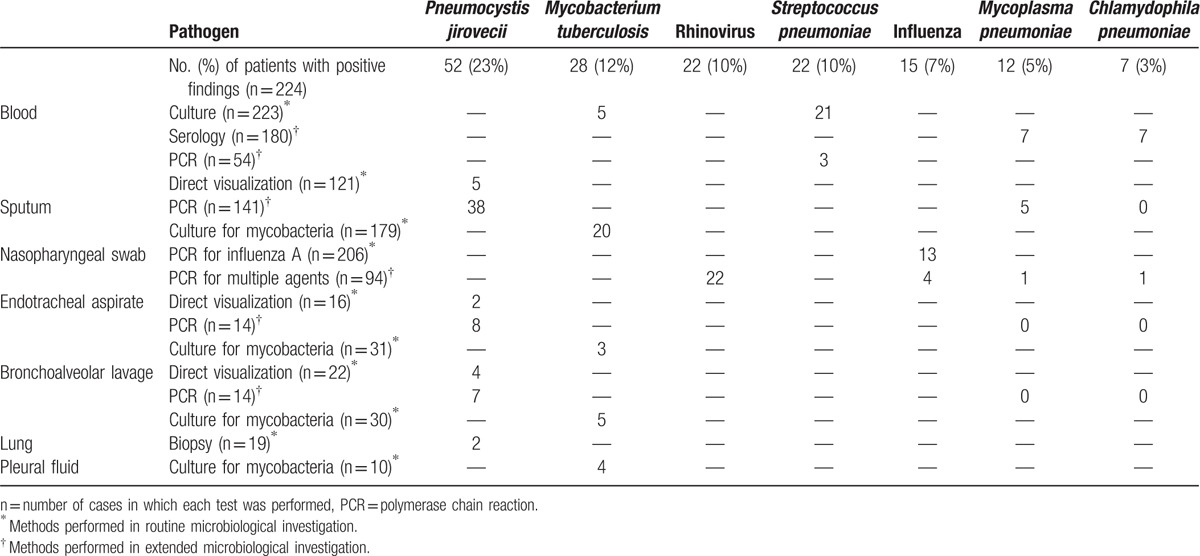

The contribution of the different methods to the etiological diagnosis of the 7 most frequent agents is shown in Table 2, PCR-based methods were essential for the diagnosis of atypical bacteria and viruses, besides contributing to ameliorate P jirovecii detection.

Table 2.

Contribution of different methods to the etiological diagnosis of the 7 most frequent pathogens causing community-acquired pulmonary infections in hospitalized patients living with HIV.

Sputum cultures for bacteria were collected for 120 patients (54%), but in many cases this occurred after the beginning of antibiotic therapy, which hampers the interpretation of results difficult (the detailed results are presented in the Supplemental Digital Content 2). The sputum cultures were used to corroborate diagnoses made by other methods and to provide antibiotic susceptibilities, but were not considered sufficient for a definitive diagnosis.

Performing an analysis of causative agents based on CD4+ T-cell count, we found that the etiology of pneumonia in those severely immunosuppressed (CD4+ T-cell count<200 cells/mm3) was similar to those who were not. P jirovecii is the only agent more frequent in the former group, an expected finding taking into account our diagnostic criteria (the detailed analysis is available in the Supplementary Table 3).

Frequencies of the 7 most common agents were compared between patients admitted during the summer and winter (as shown in the Supplementary Table 4). Due to the limited amount of included patients we were not able to fully consider seasonal variation but we found that Mycoplasma pneumonia was detected exclusively during the summer season (P = 0.01).

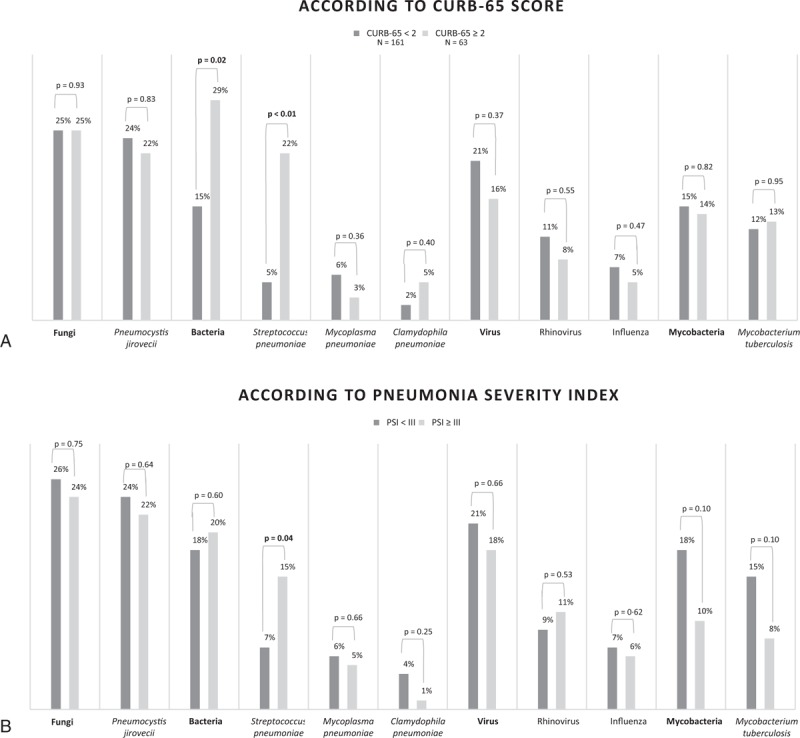

In relation to severity of disease, bacteria were most frequent among patients with higher scores, notably S pneumoniae, which was associated with severe cases as stratified by CURB-65 and PSI (Fig. 1). S pneumoniae infection frequency between individuals who referred pneumococcal vaccination when compared with individuals who denied having been vaccinated was not statistically different (6% vs 12%, P = 0.23).

Figure 1.

Microbiological findings in relation to severity of community-acquired pulmonary infections in hospitalized patients living with HIV.∗∗ Analyses restricted to the seven most common microbiological agents.

4. Discussion

This study resorted to an extended microbiological investigation that included molecular methods; therefore, an etiological diagnosis was found in a high proportion of cases (64%). Our 224 patients represent one of the largest cohorts of community-acquired pulmonary infections in adults living with HIV and is the largest cohort in South America. The most frequently identified agents in this study were P jirovecii, M tuberculosis, and S pneumoniae.

Although all patients included in the study had a clinical diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia on admission, bacterial disease was only confirmed microbiologically in 21% of them. There are recent studies that propose predictors and scores that could help the clinicians to distinguish between bacterial pneumonia and tuberculosis or P jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) in PLHIV, but their results are based on retrospective analyses; thus, their accuracy is not completely reliable.[10,11] It is difficult to predict the etiology of a pulmonary infiltrate in PLHIV based on clinical findings.

In our study, we found that bacteria were more frequent among patients with higher severity scores and S pneumoniae was more common in patients with severe disease. This finding could be due to the fact that bacterial infections tend to produce more pronounced alterations of vital signs. It is noteworthy that no severity score is validated for PLHIV and that a specific mortality risk score in this population must be further investigated.[1]

An elevated rate of mixed diagnosis (34%) was observed due to our extended investigation. This finding highlights the complexity involved in the choice of the empiric treatment for these patients and the need to perform extensive microbiological diagnosis. Mixed etiology had already been described as relatively common in PLHIV (around 11%)[10,12] and in the general population with CAP (35%).[5] A combination of viruses and bacteria was the most frequently found in those studies; however, our study stands out by encountering a large variety of different combinations.

As expected, since tuberculosis is endemic in Brazil, we found a higher proportion of cases (20%) than in nonendemic countries, such as the United States (4.3%)[12] and Spain (8.5%).[10] A small Chilean study also found a lower frequency of tuberculosis (5%) but a higher percentage of Mycobacterium avium complex infection (12%).[13] The regional prevalence of specific diseases, such as tuberculosis, can guide clinicians on the different possible diagnoses for hospitalized PLHIV affected by pulmonary disease. In high prevalence settings, tuberculosis should be always investigated.

Another interesting finding of our study is that, as we systematically investigated the atypical bacteria (M pneumoniae, C pneumoniae, and L pneumophila), we founded high rates of atypical bacterial infections (13%) in comparison with previous studies (<3%),[10,12,13] although we did not find any cases of L pneumophila. Our finding of high rates of atypical bacterial infections may support atypical coverage in the empirical treatment of these patients.

In Brazil, for PLHIV, the use of 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine is recommended. In this study, approximately one-third of the patients who knew about their vaccination status referred antipneumococcal vaccination. The frequency of S pneumoniae infection was similar for vaccinated and nonvaccinated individuals. This finding is in agreement with a systematic review that concluded that clinical evidence provides only moderate support for recommendation of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in PLHIV,[14] however the number of confirmed pneumococcal pneumonias in our study was small and this may have limited the statistical power to detect differences.

The time between the diagnosis of the HIV infection and admission in our study was long (median: 8.9 years) and the rates of regular use of HAART and of viral suppression were low (less than 20%), as well as the CD4+ T-cell counts (73% had CD4+<200 cells/mm3). Thus, our population were late presenters and presented poor adherence to HAART, as described previously[10,15] in CAP cohorts of PLHIV and that appears to be the general profile of PLHIV who require hospitalization. The immunosuppression of these patients probably contributed to the high proportion of mixed infections and to the difficulty in differentiating clinical and radiological features of the various etiological agents.

In our study, we performed an extensive laboratory investigation, using a variety of molecular methods. Following our institutional routine investigation, we would have been capable of establishing the etiology in 41% of cases, which was increased to 64% with our extended investigation. This was particularly important for PCP and viral infections.

Molecular methods can improve the diagnosis of viral respiratory infections in hospitalized patients with lower respiratory tract infections[5,16] but bring us the challenge of how to interpret these findings since is difficult to define the virus as the causative agent of pneumonia.[17] A recent review suggests that the persistence of positive PCR for virus is infrequent (≤5%) in asymptomatic subjects among the general population.[18] This indicates that the finding of viral agents in symptomatic patients reflects the presence of viruses that often contribute to the disease, but further studies in symptomatic and asymptomatic PLHIV are needed to clarify this.

When considering the diagnosis of PCP, the difficulty lies in distinguishing colonization from infection,[19] to date there has been no validated method described. In our study, we used CD4+ T-cell counts and clinical criteria to define PCP infection and in only 4 cases the diagnosis of PCP pneumonia was excluded by these criteria.

Our study has limitations. First, not all patients who met the criteria for inclusion were enrolled in the study as we used convenience sampling. Second, the specimen collection was not complete for all enrolled patients. These issues are inherent to all trials enrolling patients with CAP. We have no reason to believe that the group of patients who were not included would have been substantially different from the group of patients that we studied. Selection bias is possible but unlikely.

As in patients living with HIV mixed infections are very common we relied on at least 2 CAP definition criteria and the clinical judgment of the attending physician for the identification of possible bacterial CAP, expressed by the administration to treatment directed for bacteria. We believe this definition is valid since it reflects that real clinical situation and it is difficult to differentiate between bacterial and nonbacterial causes of community-acquired pulmonary infections in PLHIV.

Our study is a single-center study, limiting its external validation, but this is attenuated by the fact that “Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas” is the reference hospital for the metropolitan region of São Paulo (approximately 20 million inhabitants) and PLHIV comprise approximately 70% of the hospitalized patients.

In conclusion, resorting to an extended microbiological evaluation, this study was capable of defining the etiological diagnosis of a high proportion of cases of community-acquired pulmonary infections in hospitalized patients living with HIV. The main agents were P jirovecii, M tuberculosis, and S pneumoniae. Mixed infections were very frequent. Prospective studies of the etiological agents of community-acquired pulmonary infections in different settings and populations are important to guide clinical practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all medical assistants and residents of “Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas” who helped identify and care for patients, Edilene Silveira of “Instituto Adolfo Lutz” Serology Section, Vera Lucia Pagliusi Castilho and all “Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas” laboratory staff for their contribution with diagnostic issues, Adriana Coucolis and the pharmaceutics of “Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas,” who were crucial to the success of randomization.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CAP = community-acquired pneumonia, HAART = highly active antiretroviral therapy, PCP = Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, PLHIV = people living with the human immunodeficiency virus, PSI = pneumonia severity index.

This study was supported by FAPESP, São Paulo Research Foundation (grant number 2012/03834-7).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Madeddu G, Fiori ML, Mura MS. Bacterial community-acquired pneumonia in HIV-infected patients. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2010;16:201–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Murray JF. Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med 2013;34:165–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].File TM. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2003;362:1991–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Benito N, Moreno A, Miro JM, et al. Pulmonary infections in HIV-infected patients: an update in the 21st century. Eur Respir J 2012;39:730–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Johansson N, Kalin M, Tiveljung-Lindell A, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia: increased microbiological yield with new diagnostic methods. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:388–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003;58:377–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Andersson ME, Olofsson S, Lindh M. Comparison of the FilmArray assay and in-house real-time PCR for detection of respiratory infection. Scand J Infect Dis 2014;46:897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cilloniz C, Torres A, Polverino E, et al. Community-acquired lung respiratory infections in HIV-infected patients: microbial etiology and outcome. Eur Respir J 2014;43:1698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Horo K, Koné A, Koffi MO, et al. Comparative diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia and pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV positive patients. Rev Mal Respir 2015;33:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rimland D, Narvin TL, Lennox JL, et al. Pulmonary opportunistic infection study group. Prospective study of etiologic agents of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with HIV infection. AIDS 2002;16:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pérez C, García P, Calvo M, et al. Etiology of pneumonia in chilean HIV-infected adult patients. Rev Chilena Infectol 2011;28:343–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pedersen RH, Lohse N, Østergaard L, et al. The effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in HIV-infected adults: a systematic review. HIV Med 2011;12:323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Báez-Saldaña R, Villafuerte-García A, Cruz-Hervert P, et al. Association between highly active antiretroviral therapy and type of infectious respiratory disease and all-cause in-hospital mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS: a case series. PLoS One 2015;10:e0138115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oosterheert JJ, van Loon AM, Schuurman R, et al. Impact of rapid detection of viral and atypical bacterial pathogens by real-time polymerase chain reaction for patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1438–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Prina E, Ranzani OT, Torres A. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2015;386:1097–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jartti T, Jartti L, Peltola V, et al. Identification of respiratory viruses in asymptomatic subjects: asymptomatic respiratory viral infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008;27:1103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tasaka S. Pneumocystis pneumonia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults and adolescents: current concepts and future directions. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med 2015;9(suppl 1):19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.