Abstract

Leptin, the protein product of the ob gene, is essential for normal bone growth, maturation, and turnover. Peripheral actions of leptin occur at lower serum levels of the hormone than central actions because entry of leptin into the central nervous system (CNS) is limited due to its saturable transport across the blood brain barrier (BBB). We performed a study in mice to model the impact of leptin production associated with different levels of adiposity on bone formation and compared the response with well-established centrally-mediated actions of the hormone on energy metabolism. Leptin was infused (0, 4, 12, 40, 140, or 400 ng/h) for 12 days into 6-week-old female ob/ob mice (n=8/group) using sc implanted osmotic pumps. Treatment resulted in a dose-associated increase in serum leptin. Bone formation parameters were increased at EC50 infusion rates of 7–17 ng/h whereas higher levels (EC50, 40–80 ng/h) were required to similarly impact indices of energy metabolism. We then analyzed gene expression in tibia and hypothalamus at dose rates of 0, 12 and 140 ng/h; the latter dose resulted in serum leptin levels similar to WT mice. Infusion with 12 ng/h leptin increased expression of genes associated with Jak/Stat signaling and bone formation in tibia with minimal effect on Jak/Stat signaling and neurotransmitters in hypothalamus. The results suggest that leptin acts peripherally to couple bone acquisition to energy availability and that limited transport across the BBB insures that the growth promoting actions of peripheral leptin are not curtailed by the hormone’s CNS-mediated anorexigenic actions.

Keywords: animal model, bone formation, osteoblasts, neuroendocrine, bone histomorphometry

Introduction

Leptin, the protein product of the ob gene, is produced primarily by adipocytes and secreted into the vascular circulation in proportion to fat stored in adipose depots (Jequier 2002). Leptin receptors are widely expressed in peripheral tissues and the adipokine can act directly on a variety of cells to regulate their differentiation and metabolism (Anubhuti and Arora 2008; Sainz, et al. 2015). Additionally, the hormone is transported across the blood brain barrier (BBB) where it functions to regulate appetite and energy expenditure (Banks, et al. 1996).

Leptin signaling is required for normal bone growth in rodents. Absence of leptin signaling in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice or leptin receptor-deficient db/db mice and fa/fa rats results in a plethora of skeletal abnormalities, the most common of which are reduced bone length, bone- and bone compartment-specific alterations in cancellous bone volume fraction, reduced cortical thickness, and reduced cortical and total bone mass (Ealey, et al. 2006; Gat-Yablonski and Phillip 2008; Hamrick, et al. 2004; Williams, et al. 2011). At the cellular level, these abnormalities are associated with impaired endochondral ossification, lower bone formation due to reductions in osteoblast number and activity, and mild osteopetrosis due to impaired osteoclast function (Kishida, et al. 2005; Turner, et al. 2013). Not surprisingly, bone mechanical properties are often reduced and bone regeneration impaired in leptin signaling-deficient rodents (Hamann, et al. 2014; Hamann, et al. 2013; Khan, et al. 2013; Picke, et al. 2015; Wallner, et al. 2015).

Leptin receptors are expressed on many mesenchymal and hematopoietic lineage-derived cells residing in bone and cartilage, suggesting that the hormone may act locally to regulate skeletal metabolism. However, leptin-deficient rodents also develop morbid obesity, reduced core body temperature, elevated corticosteroid levels, insulin resistance, and hypogonadism, each of which, alone or in combination, may influence bone metabolism through leptin-independent pathways (Iwaniec, et al. 2009; Lindstrom 2007; Saito and Bray 1983). Indeed, equalization of weight gain, blood glucose levels, and energy balance of ob/ob to that of wild type (WT) mice worsened the skeletal phenotype associated with leptin deficiency (Turner, et al. 2014). Thus, the skeletal phenotype of leptin-deficient mice is likely due to perturbation in multiple pathways. Understanding the precise role of leptin in regulating bone growth and maturation is important because in humans low leptin levels are associated with low peak bone mass which in turn is associated with increased fracture risk (Farr and Khosla 2015).

A saturable transport mechanism is required for leptin to cross the BBB (Banks et al. 1996). As a consequence, leptin levels in peripheral circulation are typically over 10 times greater than the levels within the brain. The existence of this concentration gradient suggests higher occupancy of leptin receptor in peripheral tissues than brain (Scatchard 1948). We therefore determined the relative responsiveness of bone and other target tissues to circulating leptin levels. This was accomplished by performing a 12-day dose-response study in which physiologically relevant concentrations of the hormone were continuously infused into ob/ob mice using sc implanted osmotic pumps to model leptin production by adipose tissue.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

Six-week-old female ob/ob and homozygous WT (+/+) littermate mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The animals were placed at thermoneutral temperature (32°C) immediately upon arrival at Oregon State University and maintained singly housed on a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle. Thermoneutral housing was used to avoid mild cold stress associated with standard room temperature (Iwaniec, et al. 2016; Kokolus, et al. 2013). The ob/ob mice were randomized by weight into one of 6 treatment groups (n=8 mice/group) with leptin delivered at a dose rate of 0 (vehicle), 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.5, or 10 μg/d (equivalent to 0, 4, 12, 40, 140 or 400 ng/h or approximately equivalent to 0, 2.7, 8.2, 27, 96, and 274 μg/kg/d at treatment initiation based on a mean starting ob/ob mouse weight of 36.5 g). Vehicle (20 mM Tris-HCL, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or mouse leptin (498-OB-05M, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was infused using sc-implanted osmotic pumps (Alzet Model 1002, Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA) for the 12-day duration of study. WT mice (n=9) were untreated. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Food (Teklad 8604, Harlen Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) and water were provided ad libitum to all animals. Body weight was recorded on days −2, 0 (pump implantation), 3, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Food records were started on day −2, one day after arrival/placement into thermoneutral housing. Food intake was recorded on days −1, 3, 6, 10, and 12. Fluorochromes were administered at 9 (declomycin), 4 (calcein) and 1 (calcein) d prior to necropsy to label mineralizing bone and cartilage as described (Turner et al. 2014). Mice were fasted overnight prior to necropsy, bled by cardiac puncture, and glucose measured using a glucometer (Life Scan, Inc., Milpitas, CA). Uteri and abdominal white adipose tissue (WAT) were excised and weighed. Femora were removed, fixed for 24h in 10% buffered formalin and stored in 70% ethanol for microcomputed tomography and histomorphometric analysis. Tibiae and hypothalami were removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80ºC for mRNA analysis.

Serum chemistry

Serum leptin was measured using Mouse Leptin Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), serum osteocalcin was measured using Mouse Gla-Osteocalcin High Sensitive EIA Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), and serum CTx-1 was measured using Mouse C terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (CTx-1) ELISA kit (Life Sciences Advanced Technologies, St. Petersburg, FL) according to the respective manufacturer’s protocol. Intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) for all ELISA assays were within the manufactures’ reported CVs of ≤ 5% for osteocalcin and leptin and ≤ 10% for CTx-1.

Microcomputed Tomography

Microcomputed tomography (μCT) was used for nondestructive 3-dimensional evaluation of cancellous bone volume and architecture. Femora were scanned in 70% ethanol using a Scanco μCT40 scanner (Scanco Medical AG, Basserdorf, Switzerland) at a voxel size of 12 x 12 x 12 μm (55 kVp x-ray voltage, 145 μA intensity, and 200 ms integration time). Filtering parameters sigma and support were set to 0.8 and 1, respectively. Bone segmentation was conducted at a threshold of 245 (scale, 0–1000) determined empirically. Forty-two consecutive slices (504 μm) of cancellous bone, 45 slices (540 μm) proximal to the growth plate, were evaluated in the distal femur metaphysis. Direct cancellous bone measurements included cancellous bone volume fraction (bone volume/tissue volume, %), trabecular number (mm−1), and trabecular thickness (μm).

Histomorphometry

The methods used to measure longitudinal bone growth and static and dynamic bone histomorphometry have been described (Iwaniec, et al. 2008) with modifications for mice (Turner et al. 2013). In brief, distal femora were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and xylene, and embedded undecalcified in modified methyl methacrylate. Longitudinal sections (4 μm thick) were cut with a vertical bed microtome (Leica 2065) and affixed to slides precoated with 1% gelatin solution. One section/animal was stained for tartrate resistant acid phosphatase and counterstained with toluidine blue (Sigma, St Louis) and used for cell-based measurements. One section/animal was mounted unstained for measurement of fluorochrome labels. All data were collected using the OsteoMeasure System (OsteoMetrics, Inc., Atlanta, GA). The sampling site for the distal femoral metaphysis was located 0.25–1.25 mm proximal to the growth plate.

Cell-based measurements included osteoblast perimeter (osteoblast perimeter/bone perimeter, %) and osteoclast perimeter (osteoclast perimeter/bone perimeter, %). Fluorochrome-based measurements of bone formation included mineralizing perimeter (mineralizing perimeter/bone perimeter: cancellous bone perimeter covered with double plus half single label normalized to bone perimeter, %), 2) mineral apposition rate (the distance between two fluorochrome markers that comprise a double label divided by the 3 day interlabel interval, μm/d), 3) bone formation rate (bone formation rate/bone perimeter: calculated by multiplying mineralizing perimeter by mineral apposition rate normalized to bone perimeter, μm2/μm/y), and longitudinal bone growth (distance between the growth plate-metaphyseal junction and the declomycin label deposited in the primary spongiosa divided by the 9 day interval between label administration and necropsy, μm/day). All bone histomorphometric data are reported using standard 2-dimensional nomenclature (Dempster, et al. 2013).

EC50 Calculation

The EC50 for each response variable was the calculated dose required to achieve ½ of the maximum observed response.

Gene expression

Total RNA from tibia and hypothalamus were isolated from 5–6 mice/group and individually analyzed. Tibiae were pulverized with a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen and further homogenized in Trizol (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Hypothalamus was directly homogenized in Trizol. Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR (Life Technologies). The expression of 84 genes related to JAK/STAT signaling was determined for hypothalamus and bone using the mouse JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway RT2 Profiler PCR Array (PAMM-039Y) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The expression of 84 genes related to neurotransmitter receptors in hypothalamus and 84 genes related to bone formation and bone resorption in tibia was determined using the Mouse “Neurotransmitter Receptors” RT2 Profiler PCR Array (PAMM-060Z) and Mouse “Osteoporosis” RT2 Profiler PCR Array (PAMM-170Z), respectively. Gene expression in hypothalamus was normalized to Hsp90ab1 and in tibia was normalized to GAPDH. Relative quantification was determined (ΔΔCt method) using RT2 Profiler PCR Array Data Analysis software version 3.5 (Qiagen). Fold-change was calculated using vehicle-treated ob/ob mice as the control. Venn diagrams comparing the overlap of significantly (P < 0.05) differentially expressed genes with a ≥ 1.2-fold differential expression in ob/ob mice treated with 12 ng/h leptin and ob/ob mice treated with 140 ng/h leptin compared to ob/ob mice treated with vehicle were generated with BioVenn (Hulsen, et al. 2008).

Statistical Analysis

Mean responses were compared between six groups (vehicle control group and groups receiving leptin at 4, 12, 40, 140 or 400 ng/h) using separate one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A modified F test was used when the assumption of equal variance was violated, with Welch’s two-sample t-test used for pairwise comparisons (Welch 1955). The Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test was used when only the normality assumption was violated, in which case the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was used for pairwise comparisons. The required conditions for valid use of ANOVA were assessed using Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance, plots of residuals versus fitted values, normal quantile plots, and the Anderson-Darling test of normality. The Benjamini and Hochberg method for maintaining the false discovery rate at 5% was used to adjust for multiple comparisons (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Mean food intake (g/d) for the ob/ob vehicle group was compared to the five ob/ob groups that received leptin (4, 12, 40, 140, and 400 ng/h) using longitudinal data collected one day prior to pump implantation (−1) and on days 3, 6, 10, and 12 post implantation. In addition, a comparison of mean body weight (g) for these groups was made using longitudinal data collected on days −2, 0 (pump implantation), and 3, 6, 8, 10, 12 post implantation. Multivariate linear regression models were fit using predictor variables for leptin group, time (treated as categorical and continuous), and the group by time interaction with different covariance structures, namely independence, unstructured, and compound symmetric and autoregressive of order 1 with equal and unequal variance over time. Linear mixed models with random intercepts and slopes were also considered. Model selection was performed using the Bayesian information criterion and likelihood ratio tests. Data analysis was performed using R version 2.12 (Team 2015).

Results

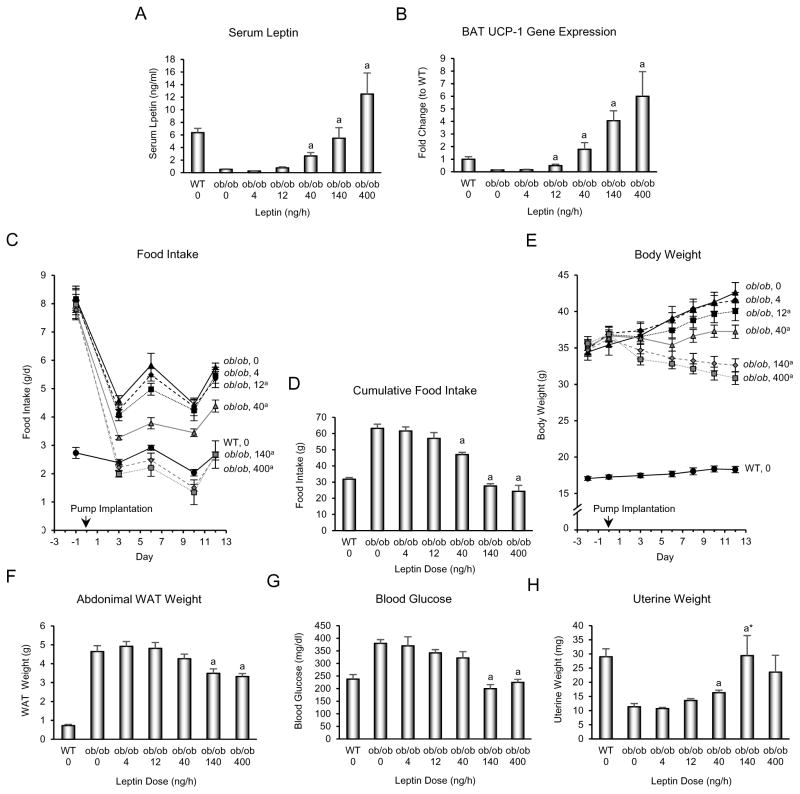

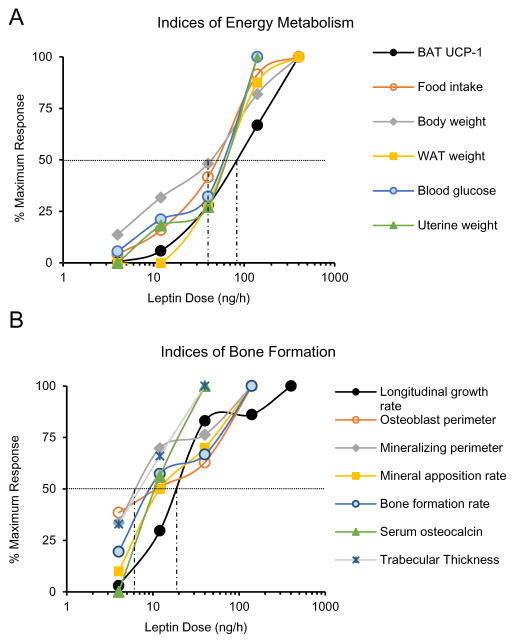

The dose-response effects of leptin administration on serum leptin and indices related to energy metabolism in ob/ob mice are shown in Fig. 1. Leptin was consistently detected in serum of ob/ob mice when infused at 40 ng/h, achieved values similar to WT mice at 140 ng/h, and was elevated compared to WT mice at 400 ng/h (Fig. 1A). Thermogenesis is regulated by a combination of sensory and sympathetic inputs while appetite and pituitary hormone release (e.g., GnRH) are regulated by leptin through a hypothalamic relay. We therefore measured UCP-1 gene expression (Fig. 1B) as an index of non-shivering thermogenesis, and food intake (Fig. 1C and D) as an index of appetite. We measured body weight (Fig. 1E), abdominal white adipose tissue weight (Fig. 1F), and blood glucose (Fig. 1G) as additional endpoints related to energy metabolism. Finally, we measured uterine weight (Fig. 1H) as an index of GnRH release (Gibson, et al. 1994). UCP-1 gene expression in BAT, food intake over the treatment interval, and body weight change over the treatment interval were significantly affected at a leptin dose of 12 ng/h, corresponding to serum leptin at or below the detection limit of the immunoassay (0.5 ng/ml), whereas changes in other endpoints, including abdominal WAT weight, blood glucose levels, and uterine weight, required 40 ng/h or higher dose rates before achieving statistical significance. As expected (Iwaniec et al. 2016), transfer of mice from room temperature to thermoneutral housing resulted in a dramatic reduction in food intake (Figure 1C), with no impact on body weight in vehicle-treated mice. Depending on endpoint measured, the EC50 of leptin for indices of energy metabolism required dose rates of 40 – 80 ng/h (Figure 2A), corresponding to serum leptin levels between 2 and 6 ng/ml. Specifically, the EC50 was 80 ng/h for UCP-1 gene expression, 53 ng/h for cumulative food intake, 40 ng/h for body weight change, 66 ng/h for WAT weight, 68 ng/h for blood glucose, and 57 ng/h for uterine weight.

Figure 1.

Effects of 12 days of sc leptin infusion on serum leptin (A), uncoupling protein-1 (UCP-1) gene expression in brown adipose tissue (BAT) (B), food intake over duration of treatment (C), cumulative food intake (D), body weight over duration of treatment (E), abdominal white adipose tissue (WAT) weight (F), blood glucose (G) and uterine weight (H) in female ob/ob mice (n=8/group). Please note the expected dramatic decrease in food intake in ob/ob mice associated with transfer from room temperature to thermoneutral housing (Iwaniec et al. 2016). Data are mean ± SE. aDifferent from vehicle-treated ob/ob mice (ob/ob), P<0.05. WT is shown as a reference group.

Figure 2.

The apparent half maximum effects (EC50) of leptin on indices of energy metabolism (A) and bone formation (B). Depending on endpoint measured, the half maximum effects of leptin on indices of energy metabolism were detected at dose rates of 40–80 ng/h whereas the half maximum effects of leptin on indices of bone formation were detected at dose rates of 7–25 ng/h. The vertical dotted lines indicate the range in EC50.

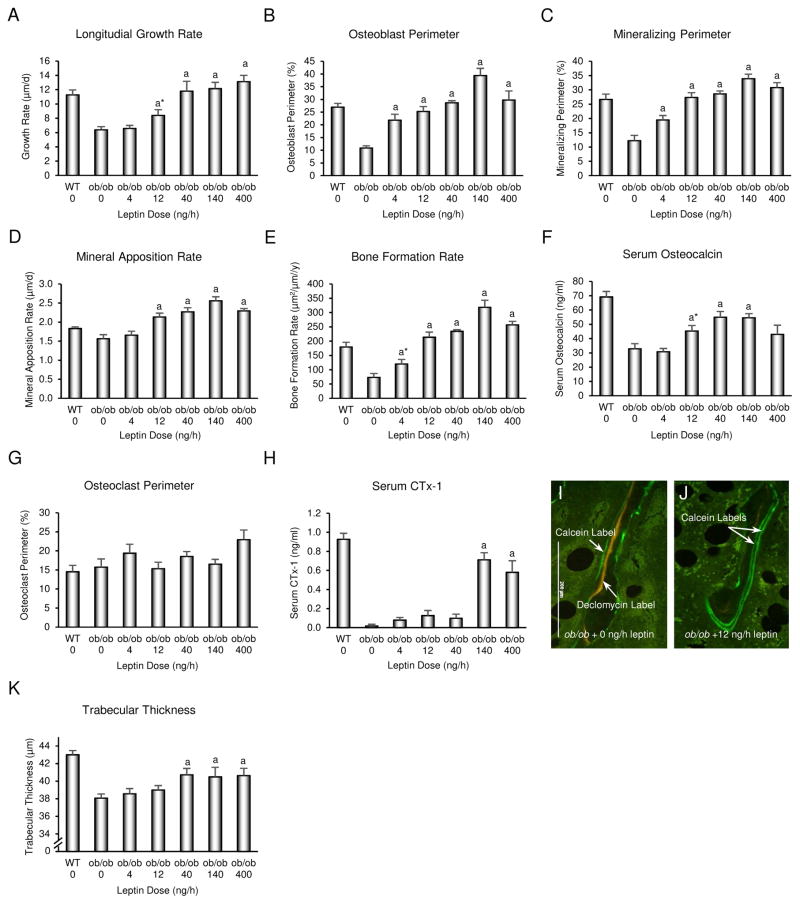

Longitudinal bone growth rate (Fig. 3A), osteoblast perimeter (Fig. 3B), mineralizing perimeter (Fig. 3C), mineral apposition rate (Fig. 3D), bone formation rate (Fig. 3E), serum osteocalcin (Fig. 3F), osteoclast perimeter (Fig. 3G), and serum CTx-1 (Fig. 3H) were determined as indices of bone growth and turnover in distal femur metaphysis. Depending upon endpoint measured, positive effects of leptin were first observed for bone growth and formation parameters at rates of 4–12 ng/h. Significant differences in osteoclast perimeter were not detected with treatment, but serum CTx-1 was increased at leptin infusion rates of 140 and 400 ng/h. Representative micrographs illustrating the low dose (12 ng/h) effects of leptin on bone formation are shown in Fig. 2I-J. The low turnover of cancellous bone in ob/ob mice is illustrated by presence of declomycin label (administered 9 d prior to sacrifice) whereas extensive double calcein label (administered 4 d and 1 d prior to sacrifice) and the absence of declomycin label in ob/ob mice treated with leptin is indicative of high turnover (Turner et al. 2013). With the exception of trabecular thickness which was increased at and above leptin infusion rates of 40 ng/h (Fig. 1K), differences in cancellous bone microarchitecture (bone volume fraction, trabecular number, connectivity density or trabecular spacing) were not detected with treatment (data not shown). This was expected, given the short duration (12 days) of study. Depending on endpoint measured, the EC50 for leptin on indices of bone formation ranged from 7–25 ng/h (Fig 2B), corresponding to serum leptin levels of < 1 ng/ml. Specifically, the half maximum response occurred at 25 ng/h for longitudinal bone growth rate, 17 ng/h for osteoblast perimeter, 7 ng/h for mineralizing perimeter, 12 ng/h for mineral apposition rate, 10 ng/h for bone formation rate, 12 ng/h for serum osteocalcin, and 7 ng/h for trabecular thickness. The EC50 was not determined for osteoclast perimeter because no significant changes were detected.

Figure 3.

Effects of 12 days of sc leptin infusion on longitudinal bone growth (A), indices of bone formation consisting of osteoblast perimeter (B), mineralizing perimeter (C), mineral apposition rate (D), bone formation rate (E), and serum osteocalcin (F), and indices of bone resorption consisting of osteoclast perimeter (G) and serum CTx-1 (H) in female ob/ob mice (n=8/group). Representative photomicrographs illustrating differences in fluorochrome labeling in ob/ob mice treated with vehicle (I) and ob/ob mice infused with 12 ng/h leptin (J). Effects of leptin on trabecular thickness, an index of bone microarchitecture, is shown in K. Data are mean ± SE. aDifferent from vehicle-treated ob/ob mice (ob/ob 0), P<0.05. WT is shown as a reference group.

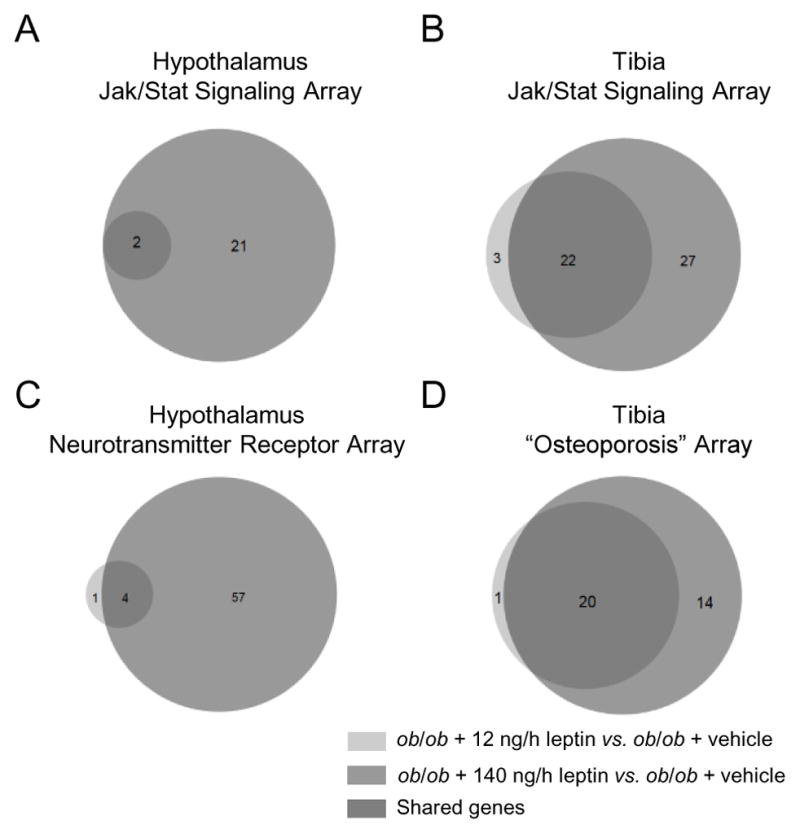

To verify the apparent dose-selective actions of leptin on hypothalamus and bone, we profiled changes in gene expression in tibia and hypothalamus in animals receiving leptin at 12 ng/h (a dose rate that increased longitudinal bone growth and bone formation but had minimal effect on energy metabolism) and 140 ng/h (a dose rate that affected both bone and energy metabolism), and compared these to vehicle-treated ob/ob controls using pathway-focused gene expression PCR arrays. Because leptin binds to its receptor to activate Jak/Stat signaling, we profiled genes related to activation of Jak/Stat signaling in hypothalamus and tibia. Functional outcomes of leptin treatment in hypothalamus and bone include increased neuronal signaling and increased bone growth and turnover, respectively. We therefore analyzed the effects of leptin on the expression of genes involved in neurotransmitter receptors in hypothalamus, and osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation and function in tibia. Differential gene expression was defined as P < 0.05 and a fold change of ≥ 1.2. As shown in the Venn diagrams (Fig. 4), leptin infusion at the dose rate of 12 ng/h had minimal effects on either Jak/Stat signaling genes or neurotransmitter receptor genes in hypothalamus (Fig. 4A and 4C). Only 2 genes and 5 genes, respectively were differentially expressed compared to ob/ob controls. In contrast, there were robust changes in Jak/Stat signaling genes (Fig. 4B) and bone cell-related genes (Fig. 4D) in tibia. A total of 25 genes involved in Jak/Stat signaling (Fig. 4B) and 21 genes involved in osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation and function (Fig. 4D) were differentially expressed in the tibia in ob/ob mice infused with leptin at a dose rate of 12 ng/h compared to vehicle-treated ob/ob controls. The 140 ng/h leptin dose resulted in robust changes in gene expression in hypothalamus and further increases in number of differentially expressed genes in tibia. All genes differentially expressed (P < 0.05) in response to leptin in hypothalamus and tibia, regardless of fold change, are identified in Tables 1–4.

Figure 4.

Venn diagrams showing the number of genes in hypothalamus (A and C) and tibia (B and D) that were differentially expressed (meeting criteria of p < 0.05 and fold-change of ≥ 1.2) in ob/ob mice (n=5) treated with 12 ng/h leptin (light gray) and ob/ob mice (n=5) treated with 140 ng/h leptin (dark gray) compared to ob/ob mice treated with vehicle (n=6). RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays were used to quantify expression of transcripts associated with JAK/STAT signaling (A and B), neurotransmitter receptors (C), and genes related to osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation and function (D). Please note the paucity of differentially expressed genes in the hypothalamus compared to tibia in mice infused with leptin at a dose rate of 12 ng/h (2 versus 25 for Jak/Stat signaling and 5 versus 21 for neurotransmitter/bone metabolism). Also note the increases in differentially expressed genes, particularly in hypothalamus, in mice infused with leptin at a dose rate of 140 ng/h. The higher dose rate results in blood leptin levels in ob/ob mice similar to WT mice.

Table 1.

Hypothalamus Jak/Stat signaling array showing significant changes for genes in ob/ob mice administered 12 ng/h or 140 ng/h leptin compared to ob/ob mice administered vehicle (0 ng/h leptin).

| Differentially Expressed Genes

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ob/ob+12 ng/h leptin vs. ob/ob+veh (n=3 genes)

|

ob/ob+140 ng/h leptin vs. ob/ob+veh (n=23 genes)

|

||||

| Symbol | Fold Change | P < | Symbol | Fold Change | P < |

|

|

|

||||

| Crk | −1.1 | 0.048 | Bcl2l1 | −1.2 | 0.009 |

| Ghr | −1.3 | 0.020 | Cdkn1a | −1.7 | 0.002 |

| Stam | −1.2 | 0.029 | Cebpb | −1.7 | 0.003 |

| Cebpd | −1.7 | 0.023 | |||

| Egfr | −1.3 | 0.019 | |||

| Fas | −1.3 | 0.010 | |||

| Fcer2a | −1.4 | 0.005 | |||

| Ghr | −1.5 | 0.002 | |||

| Il2ra | −1.7 | 0.041 | |||

| Insr | −1.5 | 0.006 | |||

| Mpl | −1.9 | 0.015 | |||

| Nos2 | −1.4 | 0.017 | |||

| Nr3c1 | −1.2 | 0.035 | |||

| Pias2 | −1.2 | 0.038 | |||

| Prlr | −1.5 | 0.040 | |||

| Ptpn11 | −1.5 | 0.010 | |||

| Smad1 | −1.2 | 0.024 | |||

| Smad2 | −1.2 | 0.039 | |||

| Smad5 | −1.3 | 0.017 | |||

| Socs1 | −1.4 | 0.020 | |||

| Sp1 | −1.2 | 0.020 | |||

| Stam | −1.3 | 0.004 | |||

| Stat4 | −2.1 | 0.001 | |||

N = 6, 5, and 5 mice in vehicle, 12 ng/h leptin, and 140 ng/h leptin group, respectively.

Table 4.

Tibia osteoporosis array showing significant changes for genes in ob/ob mice administered 12 ng/h or 140 ng/h leptin compared to ob/ob mice administered vehicle (0 ng/h leptin).

| Differentially Expressed Genes

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ob/ob+12 ng/h leptin vs. ob/ob+veh (n=23 genes)

|

ob/ob+140 ng/h leptin vs. ob/ob+veh (n=35 genes)

|

||||

| Symbol | Fold Change | P < | Symbol | Fold Change | P < |

|

|

|

||||

| Alox12 | −1.2 | 0.019 | Alox12 | −1.3 | 0.042 |

| Alpl | 1.4 | 0.004 | Alpl | 1.7 | 0.001 |

| Bglap | 1.9 | 0.001 | Bglap | 3.0 | 0.000 |

| Bmp7 | 1.2 | 0.009 | Bmp7 | 1.3 | 0.012 |

| Calcr | 2.2 | 0.007 | Calcr | 2.2 | 0.017 |

| Cd40 | 1.4 | 0.000 | Car2 | −3.8 | 0.000 |

| Col1a1 | 1.5 | 0.015 | Cd40 | 2.7 | 0.000 |

| Col1a2 | 1.4 | 0.032 | Cnr2 | 1.6 | 0.006 |

| Crtap | 1.1 | 0.030 | Col1a1 | 1.7 | 0.011 |

| Il6ra | −1.3 | 0.003 | Col1a2 | 1.6 | 0.007 |

| Lepre1 | 1.3 | 0.003 | Comt | −1.4 | 0.002 |

| Ltbp2 | 1.2 | 0.009 | Dbp | 1.8 | 0.002 |

| Mmp2 | 1.4 | 0.012 | Dkk1 | 1.3 | 0.038 |

| Npy | 1.5 | 0.025 | Enpp1 | −1.2 | 0.004 |

| Nr3c1 | 1.2 | 0.018 | Esr1 | 1.2 | 0.022 |

| Plod2 | 1.4 | 0.009 | Il15 | 1.4 | 0.019 |

| Pth1r | 1.3 | 0.003 | Il6ra | −1.3 | 0.018 |

| Sfrp4 | 1.4 | 0.002 | Itga1 | 1.1 | 0.040 |

| Sparc | 1.4 | 0.010 | Lepre1 | 1.5 | 0.000 |

| Stat1 | 1.2 | 0.003 | Lrp5 | 1.3 | 0.000 |

| Timp2 | 1.1 | 0.033 | Lrp6 | 1.2 | 0.014 |

| Tnfaip3 | 1.3 | 0.030 | Ltbp2 | 1.6 | 0.000 |

| Twist1 | 1.2 | 0.027 | Mmp2 | 1.4 | 0.017 |

| Mthfr | 1.4 | 0.008 | |||

| Nfatc1 | 1.2 | 0.002 | |||

| Npy | 1.5 | 0.044 | |||

| Nr3c1 | 1.3 | 0.000 | |||

| Plod2 | 1.5 | 0.010 | |||

| Pth1r | 1.3 | 0.027 | |||

| Sfrp4 | 1.6 | 0.004 | |||

| Sparc | 1.5 | 0.008 | |||

| Stat1 | 1.5 | 0.002 | |||

| Tnfaip3 | 1.3 | 0.006 | |||

| Tnfrsf11b | 1.2 | 0.038 | |||

| Tnfrsf1b | 1.6 | 0.001 | |||

N = 6, 5, and 5 mice in vehicle, 12 ng/h leptin, and 140 ng/h leptin group, respectively.

Discussion

This study was performed to determine the dose response effects of leptin on bone and energy metabolism. The results demonstrate that leptin acts on the skeleton at dose rates having minimal impact on energy metabolism. Specifically, leptin increased osteoblast perimeter, mineralizing perimeter, and bone formation rate at an infusion rate of 4 ng/h, and mineral apposition rate and longitudinal growth rate at an infusion rate of 12 ng/h. Leptin increased UCP-1 gene expression and decreased food intake and rate of body weight gain at an infusion rate of 12 ng/h. These dose rates (4 and 12 ng/h) resulted in serum leptin levels below or at the detection limit of the serum leptin immunoassay (0.5 ng/ml) and were insufficient to affect uterine weight, cumulative food intake, hyperglycemia, or abdominal WAT weight. Bone formation parameters were increased at EC50 ranging from 7–17 ng/h whereas higher leptin levels (EC50 of 40–80 ng/h) were required to similarly impact indices of energy metabolism. Due to the short duration of study, few changes in bone microarchitecture were anticipated or detected. However, consistent with increased bone formation, a significant increase in trabecular thickness was noted in the leptin-treated mice.

Few studies have investigated the dose-response effects of leptin. However, similar to the current findings, no effects of low sc infusion rates of leptin (<40 ng/h) for 12 days on terminal body weight, fat depots, and uterine weight were reported (Harris, et al. 1998; Trotter-Mayo and Roberts 2008). Higher doses (200 ng/h) of sc leptin were shown to be required to reduce body weight in WT mice and even higher doses (500 ng/h) were required to deplete fat stores (Halaas, et al. 1997).

The precise mechanisms mediating the physiological actions of leptin on bone are uncertain. Delivery of leptin gene into the hypothalamus of ob/ob mice reversed the skeletal abnormalities in bone architecture associated with leptin deficiency (Iwaniec, et al. 2007). Also, once daily direct delivery of high concentrations of the hormone into the hypothalamus increased bone formation (Bartell, et al. 2011). In contrast, continuous infusion of high concentrations of leptin into the hypothalamus was reported to be antiosteogenic (Ducy, et al. 2000). Direct administration of leptin or the leptin gene into the hypothalamus was originally interpreted as evidence that leptin acts indirectly through a hypothalamic relay to regulate bone metabolism (Ducy et al. 2000; Iwaniec et al. 2007; Kalra, et al. 2009; Takeda, et al. 2002). However, this conclusion is predicated on intracerebroventricular (icv) leptin remaining within the central nervous system. This assumption is not well supported because there is ample evidence indicating that icv leptin readily enters peripheral circulation. Using tracer methodology, Maness et al. (Maness, et al. 1998) investigated the fate of leptin after icv administration and found that efflux of leptin from the brain occurred with reabsorption of the cerebrospinal fluid into the blood. Efflux was not saturable and the amount of leptin in peripheral circulation after icv injection actually equaled or exceeded levels seen 20 minutes following iv administration (Maness et al. 1998). The authors concluded that icv leptin achieves exposure levels in the brain at least 300 times higher than when delivered iv, but efficient reabsorption of cerebrospinal fluid into the blood introduces leptin into peripheral circulation where the hormone can bind to receptors on target cells. This conclusion is also supported by Trotter-Mayo and Roberts (Trotter-Mayo and Roberts 2008) who compared ip and icv delivery of leptin (8 ng/h) and demonstrated that leptin delivered icv enters peripheral circulation and activates leptin receptors on thymocytes. In similar light, adoptive transfer of leptin-resistant db/db bone marrow into WT mice (db/db→WT) was shown to mimic the effects of leptin deficiency on bone without impacting centrally-mediated actions of leptin on energy metabolism (Turner et al. 2013). Importantly, icv leptin dose rates administered to ob/ob mice in bone studies described above have equaled or exceeded the dose rate (8 ng/h) used by Trotter-Mayo and Roberts (Trotter-Mayo and Roberts 2008) and would have resulted in hypothalamic leptin levels unlikely to be achieved physiologically. Thus, the exquisite sensitivity of bone to low blood levels of leptin reported in the current study combined with the knowledge that leptin is transported out of the brain into peripheral circulation following icv infusion question whether the skeletal response to icv leptin is entirely due to actions mediated centrally.

The long form of the leptin receptor (LepRb) belongs to gp130 family of cytokine receptors and binding of leptin to LepRb activates the Jak/Stat intracellular signaling pathways (Nanjappa V 2011). The robust differential expression of genes related to Jak/Stat signaling in bone following sc administration of low dose leptin (12 ng/h) provides strong evidence that leptin acts directly on one or more target cells in mouse long bones. Although the present study does not identify the precise leptin target cells in bone, osteoblast lineage cells are candidates. Osteoblasts are reported to express leptin receptors and analysis of the osteoblast transcriptome supports a role for peripheral leptin signaling in bone cell function (Grundberg, et al. 2008). Leptin has also been shown to activate multiple pathways, including Jak/Stat, in cultured osteoblast lineage cells (Burguera, et al. 2006; Gordeladze, et al. 2002; Lee, et al. 2002; Yang, et al. 2014).

In marked contrast to its actions on gene expression in tibia, leptin at 12 ng/h had minimal effects on genes related to Jak/Stat signaling in hypothalamus. However, higher levels of leptin (140 ng/h; resulting in serum leptin levels in ob/ob mice similar to that of WT mice) were associated with robust changes in gene expression in hypothalamus. In addition to the differential dose response, there was relatively little overlap in the genes regulated in tibia and hypothalamus and when there was overlap (e.g., Smads 1, 2 and 5), the genes were often differentially expressed in opposite directions. Taken together, these findings indicate that leptin targets Jak/Stat signaling in tibia as well as hypothalamus.

In the present study, sc leptin administration resulted in increased mRNA levels for bone and cartilage matrix proteins in tibia of ob/ob mice, a finding in agreement with the increase in bone formation and longitudinal bone growth and in agreement with previous studies evaluating bone metabolism in ob/ob mice (Bartell et al. 2011; Kishida et al. 2005; Turner et al. 2014). Additionally, a very low level of sc leptin replacement (12 ng/h) in ob/ob mice increased expression of genes related to BMP signaling, including Bmp 7 and Smad 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. We have previously shown that leptin deficiency results in altered expression of TGFβ1, β2 and β3, BMP 2, 3 and 6, and BMPr1a (Turner et al. 2014). Although Stat3-mediated activation of BMP/Smad signaling has been demonstrated in neural stem cells (Fukuda, et al. 2007) and BMPr1 was shown to regulate development of hypothalamic circuits critical for feeding behavior (Peng, et al. 2012), leptin-mediated BMP signaling in bone has received little attention.

After crossing the BBB, leptin binds to and activates receptors residing on POMC and AgRP/NPY-expressing neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. POMC neurons are anorexigenic and stimulated by leptin while AgRP/NPY neurons are orexigenic and inhibited by leptin. These arcuate nucleus neurons project directly to nuclei in several sites which play important roles in leptin-mediated regulation of feeding behavior (Cone 2005; Gautron and Elmquist 2011). The present study demonstrates that leptin modulates expression of a group of genes related to neurotransmission in the hypothalamus. Particularly notable were the increases in expression in dopamine receptor D5 (Drd5), bombesin receptor subtype 3 (Brs3), alpha-1D adrenergic receptor (Adra1d), serotonin receptor 2A (Htr2a), and serotonin receptor 4 (Htr4). However, these changes were not apparent at leptin levels that increased longitudinal bone growth and osteoblast number and activity.

Bone resorption is reduced in ob/ob mice, as reflected by delayed skeletal maturation (delayed replacement of calcified cartilage by bone), prolonged retention of fluorochrome labels deposited into mineralizing bone, and low serum levels of CTx-1, a biochemical marker of global bone resorption (Turner et al. 2013; Turner et al. 2014). Osteoclast perimeter is not reduced, suggesting that leptin deficiency impairs osteoclast activity rather than reducing the number of osteoclasts (Turner et al. 2014). Compared to age-matched WT mice, serum CTx-1 levels in the present study were very low in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. Leptin treatment increased serum CTx-1 but only at higher dose rates, which suggests that the positive effects of physiological doses of leptin on bone formation are not coupled to the hormone’s actions to increase bone resorption.

Leptin acts through the CNS as a permissive factor for release of the neurohormone GnRH from the pituitary (Barkan, et al. 2005), which in turn stimulates an increase in estrogen secretion from the ovaries. Estrogen deficiency induced by hypogonadism typically results in increases in bone elongation and turnover in growing rodents (Turner, et al. 1994), a response that may be antagonized by leptin. Near normalization of ovarian hormone production, as ascertained by increased uterine weight, corresponded to serum leptin levels comparable to those found in WT mice and was associated with plateauing of leptin-induced increases in indices of bone growth and turnover. Additional research will be necessary to determine whether the increased estrogen levels act to oppose the stimulatory effects of leptin.

Diabetes is closely associated with morbid obesity which may be due, in part, to development of leptin resistance (Gunnarsson 1983; Khan, et al. 2001; Schwartz, et al. 1996). Diabetes is also associated with decreased bone turnover (Pietschmann, et al. 2010). In the present study, performed in mice that are both leptin-deficient and diabetic, bone formation was increased at leptin levels having minimal impact on blood glucose levels. ob/ob mice and leptin receptor-deficient db/db mice and fa/fa rats are often used as models for type 2 diabetes. The findings of the present study agree with prior work suggesting that the low bone formation rate in these models is due to leptin signaling deficiency and not diabetes per se (Turner et al. 2014).

Leptin can increase UCP-1 by multiple mechanisms. The increased UCP-1 mRNA level in BAT induced by leptin in the present study is in agreement with prior studies (Cusin, et al. 1998; Ukropec, et al. 2006) and suggests that a combination of reduced energy intake and increased thermogenesis contributed to the dose-response effects of leptin to reduce weight gain. The importance of increased thermogenesis is consistent with studies where hypothalamic leptin gene therapy was shown to induce weight loss and maintain lower body weight in ob/ob mice and normal rodents with mild or no hypophagia (Boghossian, et al. 2007; Kalra et al. 2009).

In summary, we interpret the above as evidence that osteoblasts and growth plate cartilage cells are exquisitely sensitive to low circulating levels of leptin. The present findings, combined with results from earlier studies investigating adoptive transfer of bone marrow cells from leptin receptor-deficient db/db mice→WT mice, strongly support the hypothesis that bone formation is positively regulated by leptin through peripheral signaling. The saturable transport system, which limits delivery of leptin from the hormone’s origin in peripheral adipose tissue to the hypothalamus, may function to guarantee that adequate energy is available for important anabolic processes such as bone growth and turnover and that these actions are dissociable from the actions of the hormone to reduce appetite and increase thermogenesis. Such a mechanism would serve to insure optimal energy availability for anabolic processes to proceed to support adequate growth.

Table 2.

Tibia Jak/Stat signaling array showing signficant changes for genes in ob/ob mice administered 12 ng/h or 140 ng/h leptin compared to ob/ob mice administered vehicle (0 ng/h leptin).

| Differentially Expressed Genes

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ob/ob+12 ng/h leptin vs. ob/ob+veh (n=30 genes)

|

ob/ob+140 ng/h leptin vs. ob/ob+veh (n=52 genes)

|

||||

| Symbol | Fold Change | P < | Symbol | Fold Change | P < |

|

|

|

||||

| A2m | 2.4 | 0.000 | A2m | 6.4 | 0.002 |

| Csf1r | 1.1 | 0.040 | Akt1 | 1.4 | 0.001 |

| Cxcl9 | 1.6 | 0.011 | Bcl2l1 | −2.1 | 0.000 |

| Epor | 1.2 | 0.038 | Crk | 1.6 | 0.004 |

| Fcgr1 | 1.4 | 0.001 | Csf1r | 1.2 | 0.014 |

| Gata3 | 1.3 | 0.030 | Epor | −1.9 | 0.000 |

| Gbp2b | 1.6 | 0.001 | Fas | 1.3 | 0.019 |

| Ifnar1 | 1.3 | 0.000 | Fcer2a | 1.6 | 0.020 |

| Ifngr1 | 1.1 | 0.048 | Fcgr1 | 1.7 | 0.002 |

| Il10ra | 1.5 | 0.000 | Gbp2b | 1.6 | 0.002 |

| Il2ra | 2.6 | 0.000 | Ifnar1 | 1.6 | 0.000 |

| Il6st | 1.1 | 0.019 | Il10ra | 2.5 | 0.000 |

| Insr | 1.2 | 0.028 | Il10rb | 1.2 | 0.023 |

| Irf1 | 1.2 | 0.000 | Il2ra | 8.0 | 0.000 |

| Irf9 | 1.2 | 0.006 | Il2rg | 1.4 | 0.004 |

| Jak3 | 1.2 | 0.039 | Il4 | 1.7 | 0.013 |

| Mpl | −1.3 | 0.015 | Il4ra | 1.5 | 0.000 |

| Nr3c1 | 1.2 | 0.002 | Il6st | 1.3 | 0.001 |

| Oas1a | 1.5 | 0.008 | Irf1 | 1.8 | 0.000 |

| Pdgfra | 1.3 | 0.001 | Irf9 | 1.3 | 0.021 |

| Pias2 | 1.3 | 0.004 | Isg15 | −2.3 | 0.001 |

| Ptprc | 1.1 | 0.039 | Jak2 | −1.2 | 0.001 |

| Sh2b2 | 1.1 | 0.040 | Jak3 | 1.5 | 0.002 |

| Smad3 | 1.3 | 0.017 | Junb | 1.4 | 0.030 |

| Smad4 | 1.2 | 0.001 | Mcl1 | 1.1 | 0.034 |

| Smad5 | 1.2 | 0.001 | Mpl | −1.3 | 0.029 |

| Socs2 | 1.3 | 0.005 | Myc | 1.2 | 0.049 |

| Socs5 | 1.2 | 0.022 | Nfkb1 | 1.4 | 0.000 |

| Stat1 | 1.2 | 0.003 | Nr3c1 | 1.3 | 0.000 |

| Stat2 | 1.2 | 0.002 | Oas1a | 2.1 | 0.001 |

| Osm | 1.7 | 0.002 | |||

| Pdgfra | 1.6 | 0.000 | |||

| Pias2 | 1.5 | 0.000 | |||

| Ptpn1 | 1.1 | 0.035 | |||

| Ptprc | 1.3 | 0.011 | |||

| Spi1 | 1.3 | 0.000 | |||

| Sh2b1 | 1.3 | 0.006 | |||

| Sh2b2 | 1.2 | 0.018 | |||

| Smad1 | 1.2 | 0.004 | |||

| Smad2 | 1.1 | 0.040 | |||

| Smad3 | 1.3 | 0.003 | |||

| Smad4 | 1.4 | 0.000 | |||

| Smad5 | 1.4 | 0.002 | |||

| Socs2 | 1.3 | 0.000 | |||

| Socs5 | 1.7 | 0.007 | |||

| Stat1 | 1.5 | 0.002 | |||

| Stat2 | 1.6 | 0.000 | |||

| Stat3 | 1.3 | 0.000 | |||

| Stat5b | 1.2 | 0.031 | |||

| Stat6 | 1.4 | 0.003 | |||

| Tyk2 | 1.2 | 0.031 | |||

| Usf1 | 1.3 | 0.001 | |||

N = 6, 5, and 5 mice in vehicle, 12 ng/h leptin, and 140 ng/h leptin group, respectively.

Table 3.

Hypothalamus neurotransmitter receptor array showing significant changes for genes in ob/ob mice administered 12 ng/h or 140 ng/h leptin compared to ob/ob mice administered vehicle (0 ng/h leptin).

| Differentially Expressed Genes

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ob/ob+12 ng/h leptin vs. ob/ob+veh (n=6 genes)

|

ob/ob+140 ng/h leptin vs. ob/ob+veh (n=61 genes)

|

||||

| Symbol | Fold Change | P < | Symbol | Fold Change | P < |

|

|

|

||||

| Gabbr1 | −1.1 | 0.047 | Adra1a | −1.7 | 0.000 |

| Gabbr2 | 1.3 | 0.009 | Adra1d | 6.4 | 0.002 |

| Gabrb1 | −1.2 | 0.018 | Adra2a | −1.8 | 0.001 |

| Gria2 | −1.2 | 0.044 | Adrb2 | −1.7 | 0.005 |

| Grin2a | −1.2 | 0.010 | Avpr1a | −1.6 | 0.003 |

| Grm5 | −1.2 | 0.013 | Avpr1b | 5.5 | 0.002 |

| Brs3 | 4.5 | 0.003 | |||

| Chrm1 | −1.4 | 0.019 | |||

| Chrm5 | −1.9 | 0.000 | |||

| Chrna5 | 2.8 | 0.010 | |||

| Chrna6 | −2.0 | 0.018 | |||

| Chrna7 | −1.5 | 0.000 | |||

| Cnr1 | −1.8 | 0.000 | |||

| Drd1a | −1.2 | 0.046 | |||

| Drd5 | 7.5 | 0.004 | |||

| Gabbr1 | −1.5 | 0.000 | |||

| Gabra1 | −1.7 | 0.020 | |||

| Gabra2 | −1.9 | 0.006 | |||

| Gabra5 | −1.6 | 0.001 | |||

| Gabrb1 | −1.7 | 0.001 | |||

| Gabrb3 | −1.4 | 0.000 | |||

| Gabrd | 2.9 | 0.002 | |||

| Gabre | −1.8 | 0.001 | |||

| Gabrg1 | −1.7 | 0.002 | |||

| Gabrg3 | −2.0 | 0.001 | |||

| Gabrq | −1.5 | 0.004 | |||

| Gabrr1 | −1.7 | 0.031 | |||

| Gria1 | −1.7 | 0.002 | |||

| Gria2 | −1.9 | 0.001 | |||

| Gria3 | −1.7 | 0.003 | |||

| Grik1 | −1.5 | 0.001 | |||

| Grik2 | −1.8 | 0.000 | |||

| Grik4 | −1.4 | 0.003 | |||

| Grik5 | −1.3 | 0.017 | |||

| Grin1 | −1.4 | 0.003 | |||

| Grin2a | −1.7 | 0.000 | |||

| Grin2b | −1.5 | 0.001 | |||

| Grin2c | −1.3 | 0.013 | |||

| Grm1 | −1.5 | 0.001 | |||

| Grm5 | −1.9 | 0.000 | |||

| Grm7 | −1.6 | 0.001 | |||

| Grm8 | −1.7 | 0.000 | |||

| Grpr | −2.2 | 0.000 | |||

| Hcrtr2 | −1.7 | 0.003 | |||

| Hrh1 | 1.7 | 0.004 | |||

| Htr1a | 1.3 | 0.018 | |||

| Htr1b | −1.8 | 0.003 | |||

| Htr1f | −1.8 | 0.003 | |||

| Htr2a | 7.5 | 0.002 | |||

| Htr2b | −1.6 | 0.002 | |||

| Htr3a | −1.4 | 0.012 | |||

| Htr4 | 6.9 | 0.002 | |||

| Htr7 | −1.5 | 0.000 | |||

| Ntsr2 | −1.4 | 0.015 | |||

| Oxtr | −1.8 | 0.009 | |||

| Prokr2 | −1.3 | 0.013 | |||

| Sstr1 | −1.6 | 0.001 | |||

| Sstr2 | 1.3 | 0.033 | |||

| Sstr4 | 1.4 | 0.027 | |||

| Tacr1 | −1.2 | 0.043 | |||

| Tacr3 | −1.6 | 0.001 | |||

N = 6, 5, and 5 mice in vehicle, 12 ng/h leptin, and 140 ng/h leptin group, respectively.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the NIH (AR060913), NASA (NNX12AL24), and USDA (38420-17804).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors have nothing to declare.

Author Contribution: Study design: KAP, AJB, RTT, and UTI. Study execution: KAP. Data collection: KAP, CPW, and RTT. Data analysis: AJB. Data interpretation: KAP, AJB, CPW, RTT, and UTI. Drafting of manuscript: KAP, RTT, and UTI. Revising manuscript content: KAP, CPW, AJB, RTT, and UTI. Approving final version of manuscript: KAP, CPW, AJB, RTT, and UTI. UTI takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Bibliography

- Anubhuti, Arora S. Leptin and its metabolic interactions: an update. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:973–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Huang W, Jaspan JB, Maness LM. Leptin enters the brain by a saturable system independent of insulin. Peptides. 1996;17:305–311. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan D, Hurgin V, Dekel N, Amsterdam A, Rubinstein M. Leptin induces ovulation in GnRH-deficient mice. FASEB J. 2005;19:133–135. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2271fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartell SM, Rayalam S, Ambati S, Gaddam DR, Hartzell DL, Hamrick M, She JX, Della-Fera MA, Baile CA. Central (ICV) leptin injection increases bone formation, bone mineral density, muscle mass, serum IGF-1, and the expression of osteogenic genes in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1710–1720. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Boghossian S, Ueno N, Dube MG, Kalra P, Kalra S. Leptin gene transfer in the hypothalamus enhances longevity in adult monogenic mutant mice in the absence of circulating leptin. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1594–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burguera B, Brunetto A, Garcia-Ocana A, Teijeiro R, Esplen J, Thomas T, Couce ME, Zhao A. Leptin increases proliferation of human steosarcoma cells through activation of PI(3)-K and MAPK pathways. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:BR341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone RD. Anatomy and regulation of the central melanocortin system. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:571–578. doi: 10.1038/nn1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusin I, Zakrzewska KE, Boss O, Muzzin P, Giacobino JP, Ricquier D, Jeanrenaud B, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F. Chronic central leptin infusion enhances insulin-stimulated glucose metabolism and favors the expression of uncoupling proteins. Diabetes. 1998;47:1014–1019. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.7.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR, Parfitt AM. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2–17. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, Priemel M, Schilling AF, Beil FT, Shen J, Vinson C, Rueger JM, Karsenty G. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell. 2000;100:197–207. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealey KN, Fonseca D, Archer MC, Ward WE. Bone abnormalities in adolescent leptin-deficient mice. Regul Pept. 2006;136:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr JN, Khosla S. Skeletal changes through the lifespan-from growth to senescence. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:513–521. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Abematsu M, Mori H, Yanagisawa M, Kagawa T, Nakashima K, Yoshimura A, Taga T. Potentiation of astrogliogenesis by STAT3-mediated activation of bone morphogenetic protein-Smad signaling in neural stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4931–4937. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02435-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gat-Yablonski G, Phillip M. Leptin and regulation of linear growth. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:303–308. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f795cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautron L, Elmquist JK. Sixteen years and counting: an update on leptin in energy balance. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2087–2093. doi: 10.1172/JCI45888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MJ, Kasowski H, Dobrjansky A. Continuous gonadotropin-releasing hormone infusion stimulates dramatic gonadal development in hypogonadal female mice. Biol Reprod. 1994;50:680–685. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod50.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordeladze JO, Drevon CA, Syversen U, Reseland JE. Leptin stimulates human osteoblastic cell proliferation, de novo collagen synthesis, and mineralization: Impact on differentiation markers, apoptosis, and osteoclastic signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2002;85:825–836. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundberg E, Brandstrom H, Lam KC, Gurd S, Ge B, Harmsen E, Kindmark A, Ljunggren O, Mallmin H, Nilsson O, et al. Systematic assessment of the human osteoblast transcriptome in resting and induced primary cells. Physiol Genomics. 2008;33:301–311. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00028.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson R. The pathogenesis of type II diabetes mellitus. A brief survey. Ann Clin Res. 1983;15(Suppl 37):6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaas JL, Boozer C, Blair-West J, Fidahusein N, Denton DA, Friedman JM. Physiological response to long-term peripheral and central leptin infusion in lean and obese mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8878–8883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann C, Picke AK, Campbell GM, Balyura M, Rauner M, Bernhardt R, Huber G, Morlock MM, Gunther KP, Bornstein SR, et al. Effects of parathyroid hormone on bone mass, bone strength, and bone regeneration in male rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1197–1206. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann C, Rauner M, Hohna Y, Bernhardt R, Mettelsiefen J, Goettsch C, Gunther KP, Stolina M, Han CY, Asuncion FJ, et al. Sclerostin antibody treatment improves bone mass, bone strength, and bone defect regeneration in rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:627–638. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick MW, Pennington C, Newton D, Xie D, Isales C. Leptin deficiency produces contrasting phenotypes in bones of the limb and spine. Bone. 2004;34:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RB, Zhou J, Redmann SM, Jr, Smagin GN, Smith SR, Rodgers E, Zachwieja JJ. A leptin dose-response study in obese (ob/ob) and lean (+/?) mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:8–19. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.1.5675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsen T, de Vlieg J, Alkema W. BioVenn - a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:488. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniec UT, Boghossian S, Lapke PD, Turner RT, Kalra SP. Central leptin gene therapy corrects skeletal abnormalities in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. Peptides. 2007;28:1012–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniec UT, Dube MG, Boghossian S, Song H, Helferich WG, Turner RT, Kalra SP. Body mass influences cortical bone mass independent of leptin signaling. Bone. 2009;44:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniec UT, Philbrick KA, Wong CP, Gordon JL, Kahler-Quesada AM, Olson DA, Branscum AJ, Sargent JL, DeMambro VE, Rosen CJ, et al. Room temperature housing results in premature cancellous bone loss in growing female mice: implications for the mouse as a preclinical model for age-related bone loss. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:3091–3101. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3634-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniec UT, Wronski TJ, Turner RT. Histological analysis of bone. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;447:325–341. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-242-7_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jequier E. Leptin signaling, adiposity, and energy balance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;967:379–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra SP, Dube MG, Iwaniec UT. Leptin increases osteoblast-specific osteocalcin release through a hypothalamic relay. Peptides. 2009;30:967–973. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Narangoda S, Ahren B, Holm C, Sundler F, Efendic S. Long-term leptin treatment of ob/ob mice improves glucose-induced insulin secretion. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:816–821. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SN, DuRaine G, Virk SS, Fung J, Rowland DJ, Reddi AH, Lee MA. The temporal role of leptin within fracture healing and the effect of local application of recombinant leptin on fracture healing. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27:656–662. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182847968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida Y, Hirao M, Tamai N, Nampei A, Fujimoto T, Nakase T, Shimizu N, Yoshikawa H, Myoui A. Leptin regulates chondrocyte differentiation and matrix maturation during endochondral ossification. Bone. 2005;37:607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokolus KM, Capitano ML, Lee CT, Eng JW, Waight JD, Hylander BL, Sexton S, Hong CC, Gordon CJ, Abrams SI, et al. Baseline tumor growth and immune control in laboratory mice are significantly influenced by subthermoneutral housing temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20176–20181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304291110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Park JH, Ju SK, You KH, Ko JS, Kim HM. Leptin receptor isoform expression in rat osteoblasts and their functional analysis. FEBS Lett. 2002;528:43–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom P. The physiology of obese-hyperglycemic mice [ob/ob mice] Scientific World Journal. 2007;7:666–685. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maness LM, Kastin AJ, Farrell CL, Banks WA. Fate of leptin after intracerebroventricular injection into the mouse brain. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4556–4562. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.11.6319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjappa VRR, Muthusamy B, Sharma J, Thomas JK, Haridas Nidhina PA, Harsha1 HC, Pandey A, Anilkumar G, Keshava Prasad TS. A Comprehensive Curated Reaction Map of Leptin Signaling Pathway. J Proteomics Bioinform. 2011;4:184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Peng CY, Mukhopadhyay A, Jarrett JC, Yoshikawa K, Kessler JA. BMP receptor 1A regulates development of hypothalamic circuits critical for feeding behavior. J Neurosci. 2012;32:17211–17224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2484-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picke AK, Gordaliza Alaguero I, Campbell GM, Gluer CC, Salbach-Hirsch J, Rauner M, Hofbauer LC, Hofbauer C. Bone defect regeneration and cortical bone parameters of type 2 diabetic rats are improved by insulin therapy. Bone. 2015;82:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietschmann P, Patsch JM, Schernthaner G. Diabetes and bone. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42:763–768. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainz N, Barrenetxe J, Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Martinez JA. Leptin resistance and diet-induced obesity: central and peripheral actions of leptin. Metabolism. 2015;64:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Bray GA. Diurnal rhythm for corticosterone in obese (ob/ob) diabetes (db/db) and gold-thioglucose-induced obesity in mice. Endocrinology. 1983;113:2181–2185. doi: 10.1210/endo-113-6-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatchard G. Attractions of proteins for small molecules and ions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1948;51:660. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Baskin DG, Bukowski TR, Kuijper JL, Foster D, Lasser G, Prunkard DE, Porte D, Jr, Woods SC, Seeley RJ, et al. Specificity of leptin action on elevated blood glucose levels and hypothalamic neuropeptide Y gene expression in ob/ob mice. Diabetes. 1996;45:531–535. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, Liu X, Zhao L, Parker KL, Armstrong D, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter-Mayo RN, Roberts MR. Leptin acts in the periphery to protect thymocytes from glucocorticoid-mediated apoptosis in the absence of weight loss. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5209–5218. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RT, Kalra SP, Wong CP, Philbrick KA, Lindenmaier LB, Boghossian S, Iwaniec UT. Peripheral leptin regulates bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:22–34. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RT, Philbrick KA, Wong CP, Olson DA, Branscum AJ, Iwaniec UT. Morbid obesity attenuates the skeletal abnormalities associated with leptin deficiency in mice. J Endocrinol. 2014;223:M1–15. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RT, Riggs BL, Spelsberg TC. Skeletal effects of estrogen. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:275–300. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-3-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukropec J, Anunciado RV, Ravussin Y, Kozak LP. Leptin is required for uncoupling protein-1-independent thermogenesis during cold stress. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2468–2480. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner C, Schira J, Wagner JM, Schulte M, Fischer S, Hirsch T, Richter W, Abraham S, Kneser U, Lehnhardt M, et al. Application of VEGFA and FGF-9 enhances angiogenesis, osteogenesis and bone remodeling in type 2 diabetic long bone regeneration. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch BL. On comparison of several mean values: an alternative approach. Biometrika. 1955;38:330–336. [Google Scholar]

- Williams GA, Callon KE, Watson M, Costa JL, Ding Y, Dickinson M, Wang Y, Naot D, Reid IR, Cornish J. Skeletal phenotype of the leptin receptor-deficient db/db mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1698–1709. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WH, Tsai CH, Fong YC, Huang YL, Wang SJ, Chang YS, Tang CH. Leptin induces oncostatin M production in osteoblasts by downregulating miR-93 through the Akt signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:15778–15790. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]