Abstract

We hypothesized that women inheriting one germline mutation of the BRCA1 gene (“one-hit”) undergo cell-type-specific metabolic reprogramming that supports the high biosynthetic requirements of breast epithelial cells to progress to a fully malignant phenotype. Targeted metabolomic analysis was performed in isogenic pairs of nontumorigenic human breast epithelial cells in which the knock-in of 185delAG mutation in a single BRCA1 allele leads to genomic instability. Mutant BRCA1 one-hit epithelial cells displayed constitutively enhanced activation of biosynthetic nodes within mitochondria. This metabolic rewiring involved the increased incorporation of glutamine- and glucose-dependent carbon into tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolite pools to ultimately generate elevated levels of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA, the major building blocks for lipid biosynthesis. The significant increase of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) including the anabolic trigger leucine, which can not only promote protein translation via mTOR but also feed into the TCA cycle via succinyl-CoA, further underscored the anabolic reprogramming of BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells. The anti-diabetic biguanide metformin “reversed” the metabolomic signature and anabolic phenotype of BRCA1 one-hit cells by shutting down mitochondria-driven generation of precursors for lipogenic pathways and reducing the BCAA pool for protein synthesis and TCA fueling. Metformin-induced restriction of mitochondrial biosynthetic capacity was sufficient to impair the tumor-initiating capacity of BRCA1 one-hit cells in mammosphere assays. Metabolic rewiring of the breast epithelium towards increased anabolism might constitute an unanticipated and inherited form of metabolic reprogramming linked to increased risk of oncogenesis in women bearing pathogenic germline BRCA1 mutations. The ability of metformin to constrain the production of mitochondrial-dependent biosynthetic intermediates might open a new avenue for “starvation” chemopreventive strategies in BRCA1 carriers.

Keywords: BRCA1, hereditary breast cancer, breast cancer susceptibility, bioenergetics, glutamine

INTRODUCTION

Germline mutations of the BRCA1 gene confer a breast cancer risk in women 10- to 20-fold higher than in those with the wild-type gene [1–3]. Although hereditary tumors in women that carry BRCA1 mutations account for only a small percentage (5–10%) of breast cancers [4], the risk of developing the disease throughout the lifetime is much higher (up to 85%) in BRCA1 mutation carriers than in noncarriers. According to the “two-hit” hypothesis proposed more than 40 years ago by Knudson [5], individuals carrying a germline mutation in one copy of the BRCA1 gene require just one additional mutation in the same gene in an otherwise normal breast epithelial cell for malignant transformation. However, BRCA1-mediated tumorigenesis apparently contradicts the original “two-hit” theory conformed by other familial cancer syndromes, in which consecutive deletion of two alleles accelerates tumorigenesis. Paradoxically, the absence of both BRCA1 alleles in adult human cells induces cell proliferation defects that lead in the main to cell death. Moreover, the bi-allelic inactivation of BRCA1 commonly observed in tumors of BRCA1 cancer patients results in early embryonic lethality when reproduced in animal models [6–8]. This raises the question, how can tumor cells survive with loss of both BRCA1 alleles?

Following biallelic, homozygous inactivation of BRCA1, pre-cancerous epithelial cells must amass additional genetic alterations on other genome guardian genes to survive. Accumulating evidence suggests that breast cancer predisposition upon inactivation of a single BRCA1 allele is caused by the so-called phenomenon of haploinsufficiency associated with heterozygosity [9–20], which results in genomic instability in breast epithelial cells [13, 14, 17, 20]. This in turn may promote additional genetic changes in BRCA1 heterozygous cells, including the acquisition of new mutations that will precede and be permissive with the loss of BRCA1 (e.g., p53, ATM and CHK2). The requirement of this “extra-hit”, although incongruous from the viewpoint of familial tumorigenesis mediated by a tumor suppressor gene such as BRCA1, appears to enable cancer-prone BRCA1 “one-hit” cells to evade the cell death processes that would otherwise occur upon loss of the remaining wild-type allele.

While studies to identify genetic alterations, particularly activating changes, are warranted to better understand how the properties of BRCA1 haploinsufficiency influence the restricted tissue distribution of BRCA1 tumorigenesis, it is important to consider that breast malignancy can occur early in women with a germline BRCA1 mutation, whereas other BRCA1 mutation carriers develop disease much later or not at all [21]. From a strictly genetic perspective, if genetic instability caused by loss of BRCA1 allows the acquisition of mutations in critical checkpoint genes during puberty, this phenomenon would enable rare BRCA1 null cells to escape death and proliferate, leading to early breast cancer onset. If a majority or all cells with somatic inactivation of the remaining wild-type BRAC1 allele succumb to checkpoint-mediated cell death, tumors would occur much later in the life of a woman with an inherited BRCA1 mutation. Alternatively, the incomplete penetrance associated with inherited BRCA1 mutations might reflect the fact that non-genetic modifiers have an important role in determining cancer risk among BRCA1 carriers. Although reproductive, dietary and lifestyle factors remain controversial with regards to their ability to influence BRCA1-related cancer risk [22–25], the common assumption that the fundamental mechanism(s) underlying breast cancer predisposition are expected to be different in BRCA1 mutation carriers than in the general population further complicates the scenario.

By considering metabolic networks that could reconcile both genetic and nongenetic causal mechanisms in BRCA1-driven tumorigenesis [16, 26–30], we herein tested the challenging hypothesis that BRCA1 haploinsufficiency drives metabolic rewiring in breast epithelial cells, acting as an early but suppressible “hit” that pushes BRCA1 one-hit cells toward malignant transformation. On the one hand, metabolic analyses of human cancers are beginning to indicate that mitochondrial damage and altered metabolism can precede malignancy [31–33]. On the other hand, induction of genomic instability comes at the cost of significant stress, which obliges cells to modify their energy use to provide adaptation against genetic changes as well as to promote their survival and growth [34–36]. Thus, normal breast epithelial cells bearing a single inherited “hit” in BRCA1 might become pre-equipped with a metabolic phenotype capable of supporting the high energetic and anabolic requirements for progression to a fully malignant phenotype. We present strong evidence for an unforeseen one-hit inherited metabolic trait linked to increased risk for oncogenesis in women with pathogenic germline BRCA1 mutations that might be suppressible by the anti-diabetic drug metformin.

RESULTS

Mutation of a single BRCA1 allele dramatically alters the metabolomic signature of normal-like breast epithelial cells

We utilized our recently developed targeted metabolomics platform coupling gas chromatography with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry and an electron impact source (GC-EI-QTOF-MS), which allows the simultaneous measurement of 30 selected metabolites representative of the catabolic and anabolic status of key metabolic nodes. These metabolites include not only representatives of glycolysis and the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, but also other biosynthetic routes such as pentose phosphate pathway, amino acid metabolism and de novo fatty acid biogenesis [37, 38].

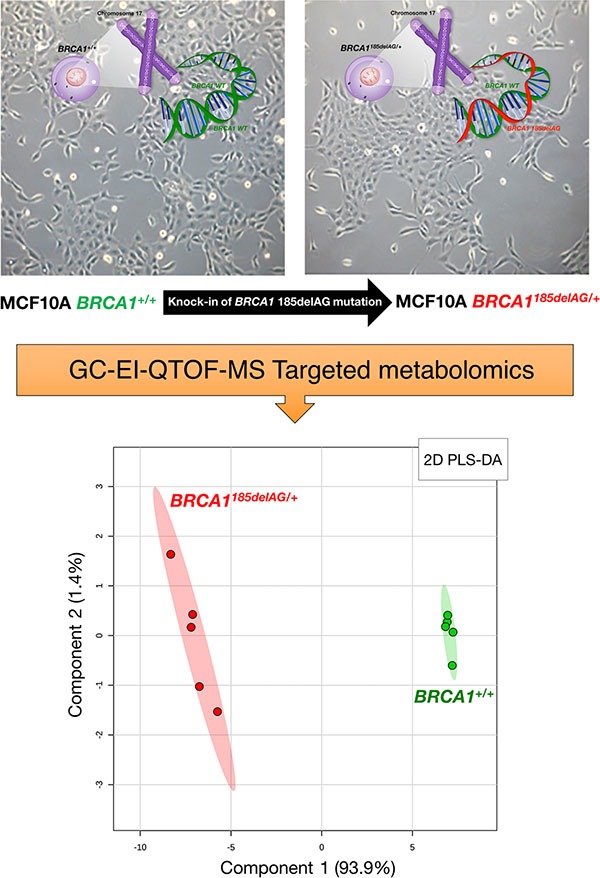

To model BRCA1 haploinsufficiency, we employed a well-defined experimental system using MCF10A breast epithelial cells, a spontaneously immortal and genetically stable basal-like model with wild-type p53. A common pathogenic mutation, 185delAG, a 2-bp deletion in the coding region close to the N-terminus, was introduced into BRCA1 by gene targeting [14; Figure 1, top]. This heterozygous mutation leads to haploinsufficiency and genomic instability in MCF10A cells, and therefore accurately mimics the cell-autonomous consequences of one-hit BRCA1 inactivation. Metabolite-based clustering obtained by partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) model revealed a clear and significant separation between BRCA1185delAG/+ heterozygous cells and parental BRCA1+/+ cells in two-dimensional (2D) score plots (Figure 1, bottom).

Figure 1. Metabolomic profiling of BRCA1 haploinsufficient breast epithelial cells.

Top. Inactivating mutation of a single BRCA1 allele leads to haploinsufficiency, which results in genomic instability in the spontaneously immortalized MCF10A cell line [14]. Bottom. 2D PLS-DA models of the GC-EI-QTOF-MS-based metabolomic profiling for the BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient and BRCA1+/+ wild-type cell groups.

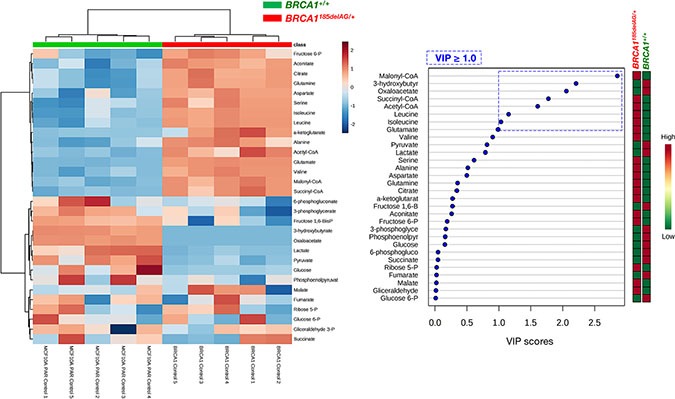

Heatmap visualization, commonly used for unsupervised clustering, revealed distinct segregation of metabolites in BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ groups (Figure 2, left), pointing to a metabolic signature associated with the human BRCA1 mutation carrier state. In general, cellular metabolites related to a highly anabolic (biosynthetic) phenotype were more overrepresented in BRCA1185delAG/+ cells than in BRCA1+/+ cells, which significantly upregulated metabolites related to an oxidative phenotype (Figure 3). Accordingly, when the distinct metabolites between groups were selected with the criterion of variable importance in the projection (VIP ≥ 1) in the PLS-DA model, several coenzyme A (CoA) derivatives, such as acetyl-CoA, succinyl-CoA, and particularly malonyl-CoA, as well as the branched-chain amino acids (BCCAs) valine, isoleucine, and leucine, were significantly higher in BRCA1185delAG/+ cells than in BRCA1+/+ cells (Figure 2, right).

Figure 2. Inactivating mutation of a single BRCA1 allele leads to metabolic reprogramming towards an anabolic phenotype.

Left. Heatmap visualization and hierarchical clustering analysis with MetaboAnalyst's data annotation tool for the BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient and BRCA1+/+ wild-type cell groups. Rows: metabolites; columns: samples; color key indicates metabolite expression value (blue: lowest; red: highest). Right. VIP rank-score of quantified metabolites in BRCA1185delAG/+haploinsufficient and BRCA1+/+ wild-type cell groups. Dashed blue box indicates metabolites that achieved VIP scores above 1.0.

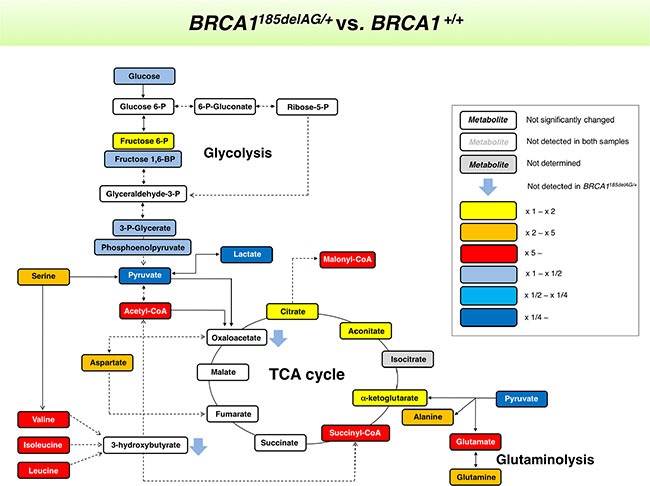

Figure 3. BRCA1 “one-hit”-induced metabolic changes in breast epithelial cells.

Metabolites in BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient cells were extracted and quantitatively analyzed by GC-EI-QTOF-MS and compared with metabolites from control BRCA1+/+ isogenic parental cells. Significantly increased and decreased metabolites are shown using yellow-red and light blue-dark blue color scales, respectively.

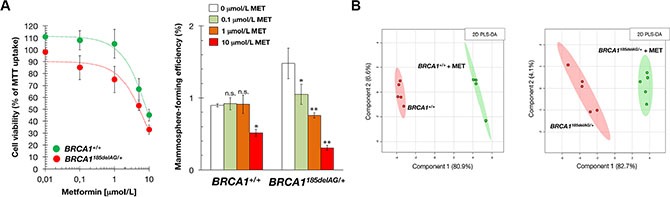

The anti-diabetic biguanide metformin reduces tumor-initiating capacity of breast epithelial BRCA1 one-hit cells

Because metformin has attracted interest as an antitumor agent in cancer prevention and treatment [39–53], we explored the possible impact of metformin treatment on metabolic rewiring induced by pathogenic mutation of a single BRCA1 allele. Although both BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ isogenic cells exhibited dose-dependent proliferative arrest in response to increasing concentrations of metformin as determined by MTT uptake, BRCA1185delAG/+ cells were more sensitive to the cytostatic effects of metformin than BRCA1+/+ parental cells (Figure 4A, left).

Figure 4. Treatment with the mitochondrial poison metformin suppresses mammosphere-initiating capacity of BRCA1 haploinsufficient breast epithelial cells.

(A) Left. Relative cell viability of BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ cells treated with graded concentrations of metformin. Cell viability was normalized to the condition with no metformin. Mean (circles) and SD (bars) were calculated from three biological replicates. Right. Seven-day MSFE of BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ cells seeded in mammosphere medium in the absence or presence of graded concentrations of metformin and expressed as percentage mean (columns) ± SD (bars). Re-feeding of mammosphere cultures with metformin and/or sphere medium was performed on day 3 and 5. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus the corresponding controls. (B) Two-dimensional PLS-DA models of the GC-EI-QTOF-MS-based metabolomic profiling for the untreated and metformin-treated BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient and BRCA1+/+ wild-type cell groups (48 h treatment, 1 mmol/L metformin [MET]).

BRCA1 is involved in regulating stemness and differentiation in stem and breast progenitor cells [54–57]. Accordingly, BRCA1 haploinsufficiency increases three-dimensional clonal growth and proliferation of primary mammary epithelial cells from BRCA1 mutation carriers. As one of the properties of stem/progenitor cells is their ability to survive, proliferate and differentiate under anchorage-independent conditions and generate spheroid structures [58], we tested the ability of BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ cells to form tumorspheres (mammospheres) in suspension culture in the presence of metformin. Mammosphere forming-efficiency (MSFE) was calculated by dividing the number of sphere-like structures formed after 7 days (diameter > 50 μm) by the original number of cells seeded. A significantly higher number of bona fide mammospheres were formed from nontreated BRCA1185delAG/+ one-hit epithelial cells than nontreated BRCA1+/+ cells (Figure 4A, right), strongly suggesting that BRCA1 haploinsufficiency led to a significant expansion of the stem cell-like population. This stronger spheroid formation capacity of BRCA1185delAG/+ cells was significantly and dose-dependently reduced by metformin, whereas baseline MSFE of BRCA1+/+ parental cells remained largely unresponsive to the drug (Figure 4A, right). Metformin-induced suppression of mammosphere formation (e.g., ≈50% reduction at 1 μmol/L metformin) was not attributed to non-specific toxic effects since cell viability in monolayer cultures remained as high as 75 ± 11% in the presence of an identical concentration of metformin (Figure 4A, left).

Metformin suppresses mitochondrial-dependent production of biosynthetic intermediates in BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells

We next explored whether the ability of metformin to reduce tumor-initiating capacity in BRCA1 one- hit cells correlated with a capacity to alter the highly anabolic (biosynthetic) signature driven by BRCA1 haploinsufficiency. PLS-DA models revealed a significant separation between untreated and metformin-treated breast epithelial cells regardless of their BRCA1 status (Figure 4B). Thus, we speculated that the ability of metformin to suppress mammosphere formation in BRCA1 one-hit cells related to its ability to specifically deactivate biosynthetic mitochondrial nodes in BRCA1 one-hit cells but not in BRCA1+/+ cells.

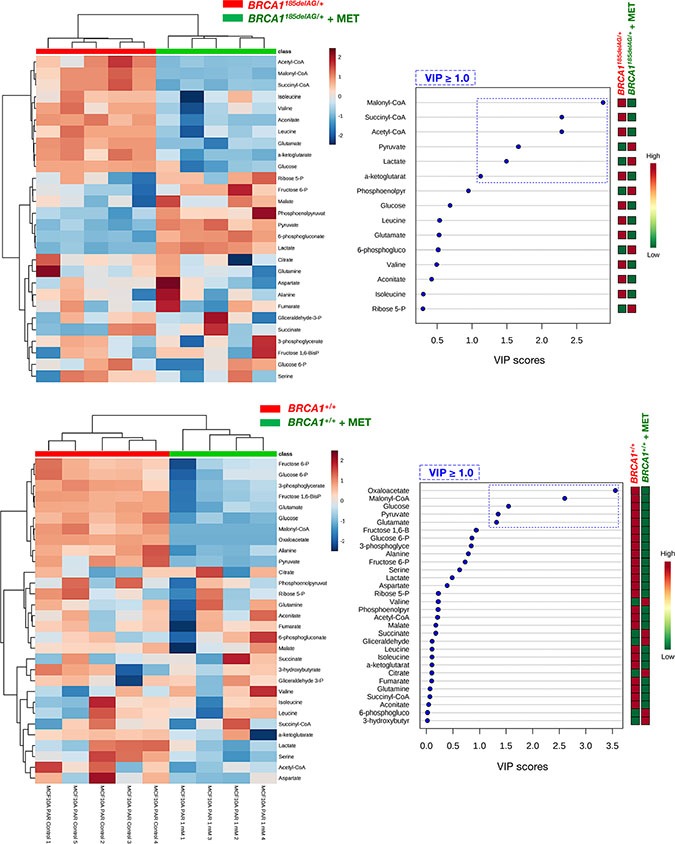

A general screen of the 30 selected metabolites using Heatmap visualization showed distinct segregation and revealed the ability of metformin to reverse the metabolomic signature and anabolic phenotype of mutant BRCA1 one-hit cells by: a) shutting down mitochondria-driven generation of lipogenic precursors, and b) reducing the pool of BCAAs for protein synthesis and/or anaplerotic fueling of TCA cycle metabolism (Figure 5, top). When VIP scores ≥ 1 in the PLS-DA model were used to maximize the difference of metabolic profiles between untreated and metformin-treated BRCA1185delAG/+ groups, it was noteworthy that the subset of metabolites majorly impacted by metformin included the basic building blocks for the de novo synthesis of fatty acids malony-CoA and acetyl-CoA, the TCA metabolites succinyl-CoA and α-ketoglutarate, and the end-products of glycolysis lactate and pyruvate (Figure 5, top). A largely different metabolic rearrangement occurred after metformin treatment of BRCA1+/+ cells (Figure 5, bottom), strongly suggesting that metabolic responses to metformin-induced inhibition of complex I-dependent mitochondrial respiration depended on the intrinsic engagement of a given cell type to mitochondrial metabolism [59, 60].

Figure 5. Metformin treatment specifically and significantly reverses the anabolic signature of BRCA1 haploinsufficient breast epithelial cells.

Left panels. Heatmap visualization and hierarchical clustering analyses with MetaboAnalyst's data annotation tool for the untreated and metformin-treated (1 mmol/L MET; 48 h) BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient (top) and BRCA1+/+ wild-type (bottom) cell groups. Rows: metabolites; columns: samples; color key indicates metabolite expression value (blue: lowest; red: highest). Right panels. VIP rank-score of quantified metabolites in untreated and metformin-treated BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient (top) and BRCA1+/+ wild-type (bottom) cell groups. Dashed blue box indicates metabolites that achieved VIP scores above 1.0.

Quantitative assessment of metabolite concentrations confirmed that treatment with metformin fully suppressed (> 90% reduction) the major accumulation (≈162-fold increase) of malonyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA (23-fold increase) induced by BRCA1185delAG/+ mutation (Table 1, Figure 6) Similarly, treatment with metformin reduced, by ≈90%, the 27-fold accumulation of succinyl-CoA and, by 60%, the levels of α-ketoglutarate in BRCA1185delAG/+ cells (Table 1). Although less dramatically, 1 mmol/L metformin reduced by up to 40% the 5-, 7- and 6-fold accumulation of the BCAAs valine, leucine, and isoleucine, respectively, in BRCA1185delAG/+ cells. Conversely, metformin treatment increased, by ≈4- and 5-fold, the intracellular levels of lactate and pyruvate in BRCA1185delAG/+ cells, respectively.

Table 1. Concentration (in μM/mg of protein ± SEM) and fold change of bioenergetics metabolites in parental BRCA1+/+ and their BRAC1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient derivatives.

| Metabolite | BRCA1+/+ | BRCA1+/– | Fold-change [BRCA1+//BRCA1+/+] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malonyl-CoA | Control | 0.0016 ± 0.0002 (1.0) | 0.26 ± 0.05 (1.00) | [162.5] |

| + 1 mM MET | N.D. | 0.01658 ± 0.0007 (0.06) | - | |

| Succinyl-CoA | Control | 0.012 ± 0.001 (1.0) | 0.32 ± 0.07 (1.0) | [26.7] |

| + 1 mM MET | 0.012 ± 0.002 (1.0) | 0.035 ± 0.003 (0.1) | ||

| Acetyl-CoA | Control | 0.015 ± 0.001 (1.0) | 0.34 ± 0.09 (1.00) | [23] |

| + 1 mM MET | 0.0122 ± 0.0006 (0.8) | 0.032 ± 0.001 (0.09) | ||

| 3-Hydroxybutyrate | Control | 5.2 ± 0.4 (1.0) | N.D. | - |

| + 1 mM MET | 5.2 ± 0.2 (1.0) | N.D. | - | |

| 3-Phosphoglycerate | Control | 2.9 ± 0.2 (1.0) | 2.2 ± 0.2 (1.0) | [0.8] |

| + 1 mM MET | 1.2 ± 0.1 (0.4) | 2.1 ± 0.5 (1.0) | ||

| 6-Phosphogluconate | Control | 6.9 ± 0.2 (1.0) | 6.3 ± 0.1 (1.0) | [0.9] |

| + 1 mM MET | 7.2 ± 0.8 (1.0) | 10.1 ± 0.2 (1.6) | ||

| Aconitate | Control | 0.31 ± 0.02 (1.0) | 0.49 ± 0.01 (1.0) | [1.6] |

| + 1 mM MET | 0.31 ± 0.05 (1.0) | 0.34 ± 0.01 (0.7) | ||

| α-ketoglutarate | Control | 0.625 ± 0.003 (1.0) | 1.04 ± 0.09 (1.0) | [1.7] |

| + 1 mM MET | 0.56 ± 0.05 (0.9) | 0.37 ± 0.04 (0.4) | ||

| Alanine | Control | 112 ± 11 (1.0) | 277 ± 21 (1.0) | [2.5] |

| + 1 mM MET | 49 ± 4 (0.4) | 261 ± 19 (0.9) | ||

| Aspartate | Control | 112 ± 19 (1.0) | 258 ± 11 (1.0) | [2.3] |

| + 1 mM MET | 72 ± 6 (0.6) | 224 ± 18 (0.9) | ||

| Citrate | Control | 7.0 ± 0.5 (1.0) | 12.7 ± 0.4 (1.0) | [1.8] |

| + 1 mM MET | 7.9 ± 0.9 (1.1) | 11.6 ± 0.7 (0.9) | ||

| Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate | Control | 0.55 ± 0.01 (1.0) | 0.35 ± 0.05 (1.0) | [0.6] |

| + 1 mM MET | 0.21 ± 0.03 (0.4) | 0.44 ± 0.07 (1.3) | ||

| Fructose 6-phosphate | Control | 1.24 ± 0.09 (1.0) | 1.73 ± 0.06 (1.0) | [1.4] |

| + 1 mM MET | 0.6 ± 0.1 (0.5) | 2.03 ± 0.08 (1.2) | ||

| Fumarate | Control | 4.0 ± 0.2 (1.0) | 3.8 ± 0.2 (1.0) | [1.0] |

| + 1 mM MET | 3.7 ± 0.5 (1.0) | 4.0 ± 0.5 (1.0) | ||

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate | Control | 2.6 ± 0.4 (1.0) | 2.6 ± 0.2 (1.0) | [1.0] |

| + 1 mM MET | 2.9 ± 0.4 (1.1) | 2.6 ± 0.5 (1.0) | ||

| Glucose | Control | 7.6 ± 0.7 (1.0) | 5.66 ± 0.04 (1.0) | [0.7] |

| + 1 mM MET | 1.6 ± 0.2 (0.2) | 3.2 ± 0.5 (0.6) | ||

| Glucose 6-phosphate | Control | 2.7 ± 0.3 (1.0) | 2.6 ± 0.3 (1.0) | [1.0] |

| + 1 mM MET | 1.2 ± 0.2 (0.4) | 2.3 ± 0.4 (0.9) | ||

| Glutamate | Control | 21.8 ± 0.4 (1.0) | 126 ± 2 (1.0) | [5.8] |

| + 1 mM MET | 5.9 ± 0.9 (0.3) | 78 ± 4 (0.6) | ||

| Glutamine | Control | 7.5 ± 0.4 (1.0) | 13.9 ± 0.4 (1.0) | [1.8] |

| + 1 mM MET | 7.4 ± 1.5 (1.0) | 13.4 ± 0.3 (1.0) | ||

| Isoleucine | Control | 15 ± 3 (1.0) | 87 ± 4 (1.0) | [5.8] |

| + 1 mM MET | 13 ± 2 (0.9) | 68 ± 7.4 (0.8) | ||

| Lactate | Control | 1638 ± 293 (1.0) | 373 ± 16 (1.0) | [0.2] |

| + 1 mM MET | 944 ± 125 (0.6) | 1490 ± 115 (4.0) | ||

| Leucine | Control | 35 ± 7 (1.0) | 260 ± 12 (1.0) | [7.4] |

| + 1 mM MET | 32 ± 6 (0.9) | 161 ± 14 (0.6) | ||

| Malate | Control | 2.06 ± 0.05 (1.0) | 2.2 ± 0.1 (1.0) | [1.1] |

| + 1 mM MET | 1.834 ± 0.3 (0.9) | 2.7 ± 0.2 (1.2) | ||

| Oxaloacetate | Control | 39 ± 2 (1.0) | N.D. | - |

| + 1 mM MET | N.D. | N.D. | ||

| Phosphoenolpyruvate | Control | 2.1 ± 0.3 (1.0) | 1.5 ± 0.1 (1.0) | [0.7] |

| + 1 mM MET | 1.7 ± 0.3 (0.8) | 3.0 ± 0.3 (2.0) | ||

| Pyruvate | Control | 35 ± 6 (1.0) | 7.7 ± 0.7 (1.0) | [0.2] |

| + 1 mM MET | 8.0 ± 0.3 (0.2) | 36 ± 4 (4.7) | ||

| Ribose 5-phosphate | Control | 1.8 ± 0.3 (1.0) | 1.9 ± 0.2 (1.0) | [1.0] |

| + 1 mM MET | 1.5 ± 0.3 (0.8) | 2.5 ± 0.2 (1.3) | ||

| Serine | Control | 118 ± 18 (1.0) | 338 ± 28 (1.0) | [2.9] |

| + 1 mM MET | 59 ± 5 (0.5) | 301 ± 27 (0.9) | ||

| Succinate | Control | 24 ± 3 (1.0) | 22 ± 4 (1.0) | [0.9] |

| + 1 mM MET | 29 ± 6 (1.2) | 24 ± 4 (1.1) | ||

| Valine | Control | 15 ± 1 (1.0) | 74 ± 4 (1.0) | [4.9] |

| + 1 mM MET | 19 ± 3 (1.3) | 48 ± 5 (0.6) |

Decimals were set according to the first significant digit of the measured SEM.

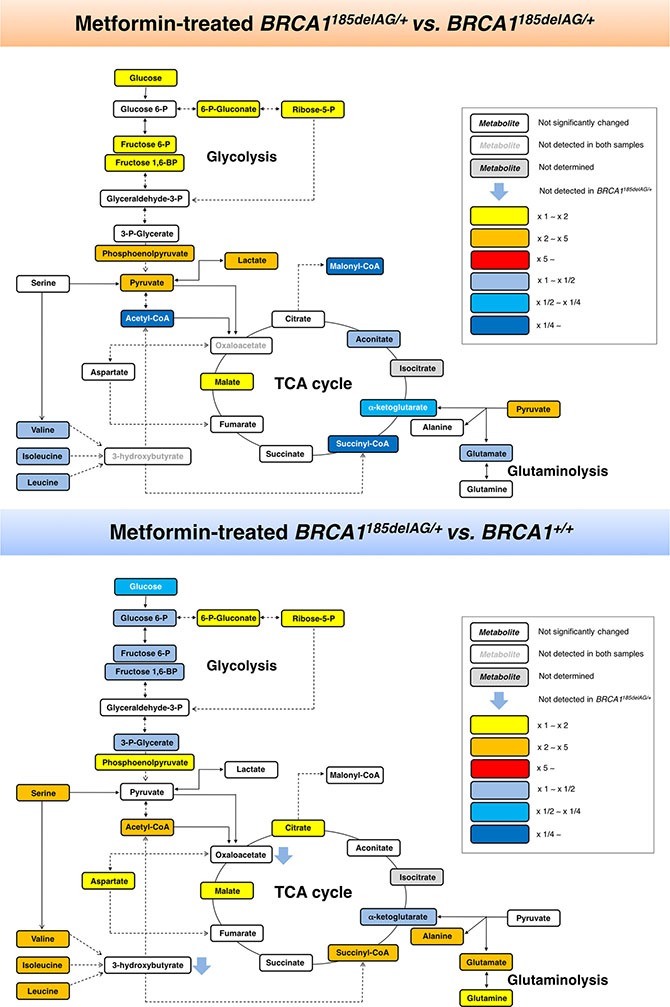

Figure 6. Metformin-induced metabolic changes in BRCA1 haploinsufficient breast epithelial cells.

Metabolites in metformin (MET)-treated BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient cells were extracted and quantitatively analyzed by GC-EI-QTOF-MS and compared with metabolites from either untreated BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient cells (top) or untreated BRCA1+/+ isogenic parental cells (bottom). Significantly increased and decreased metabolites are shown using yellow-red and light blue-dark blue color scales, respectively.

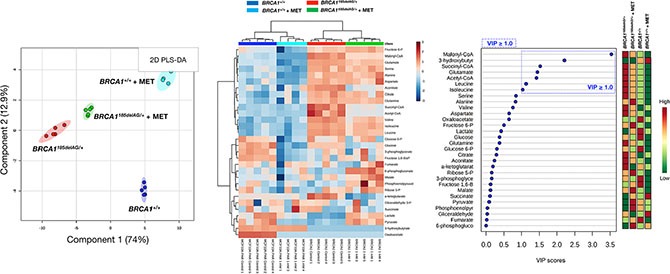

Although the key carbon donor for de novo fatty acid synthesis, malonyl-CoA, remained one of the most affected metabolites in metformin-treated BRCA1+/+ cells, it was noteworthy that this treatment triggered a largely different metabolic rearrangement when compared with BRCA1185delAG/+ cells (Figure 7). Moreover, although metformin treatment of BRCA1185delAG/+ cells failed to restore the metabolic portrait originally exhibited by BRCA1+/+ cells, a global assessment of untreated BRCA1+/+, metformin-treated BRCA1+/+, untreated BRCA1185delAG/+, and metformin-treated BRCA1185delAG/+ classes based on the VIP parameter once again revealed that the CoA derivatives malonyl-CoA, succinyl-CoA, and acetyl-CoA, and the BCCAs leucine and isoleucine were the key metabolites responsible for separation of all the metabolomic classes (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Metformin treatment generates a new metabolomic signature in BRCA1 haploinsufficient breast epithelial cells.

Left. Two-dimensional PLS-DA models to view the separation of the 4 groups (untreated BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient cells, metformin [MET]-treated BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient cells, untreated BRCA1+/+ wild-type cells, and metformin-treated BRCA1+/+ wild-type cells) following GC-EI-QTOF-MS-based metabolomic profiling. Middle. Heatmap to view the agglomerative hierarchical clustering of the 4 groups analyzed with MetaboAnalyst's data annotation tool. Rows: metabolites; columns: samples; color key indicates metabolite expression value (blue: lowest; red: highest). Right. VIP rank-score of quantified metabolites in the 4 groups. Dashed blue box indicates metabolites that achieved VIP scores above 1.0.

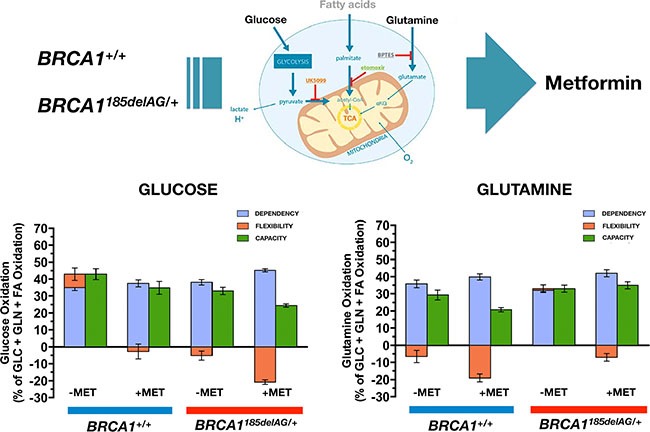

Metformin differentially impacts the capacity of normal-like and BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells to oxidize glucose and glutamine

Because mitochondrial access to different fuels such as glucose and glutamine significantly impacts a variety of biological processes, we assessed whether BRCA1+/+ and BRCA1185delAG/+ breast epithelial cells might differentially adjust fuel oxidation to match nutrient availability while meeting energy demand. Taking advantage of the Seahorse XF Mito Fuel Flex Test, a comprehensive method for measuring mitochondrial fuel usage in live cells, we measured the dependency (i.e., the requirement for a specific fuel to meet metabolic demand), capacity (i.e., the ability to use a specific fuel to meet energy demand), and flexibility (i.e., the difference between the amount they need and the amount they could use) of BRCA1+/+ and BRCA1185delAG/+ breast epithelial cells to oxidize glucose and glutamine when pre-challenged with metformin (5 μmol/L, 24 h). BRCA1185delAG/+ breast epithelial cells exhibited a significantly lower capacity to use and increase the oxidation of glucose when trying to compensate for BPTES- and etomoxir-induced inhibition of alternative fuel pathways (i.e., glutamine oxidation and long chain fatty acid oxidation, respectively), a mitochondrial fuel usage that was further exacerbated when BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells were pre-exposed to metformin (Figure 8, left). Conversely, BRCA1185delAG/+ breast epithelial cells exhibited a significantly higher capacity to use and increase the oxidation of glutamine when trying to compensate for UK5099 and etomoxir-induced inhibition of alternative fuel pathways (i.e., glucose oxidation and long chain fatty acid oxidation, respectively), a mitochondrial fuel usage that was further exacerbated when BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells were pre-exposed to metformin (Figure 8, right).

Figure 8. Metformin treatment differentially impacts mitochondrial fuel usage in BRCA1 haploinsufficient breast epithelial cells.

Figure shows the dependency, capacity, and flexibility of BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient and BRCA1+/+ wild-type cells to oxidize the mitochondrial fuels glucose (left) and glutamine (right) in the absence or presence of metformin.

Metformin reverts the activation of mTOR-related signaling in BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells

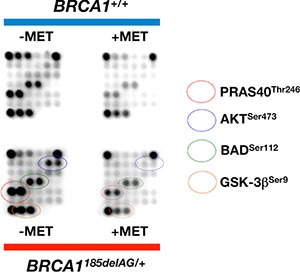

To explore whether the apparent anabolic reprogramming of BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells involved the activation of signal transduction mechanisms linked to mTOR, we took advantage of commercially available slide-based antibody arrays for the simultaneous assessment of 18 well-characterized intracellular signaling molecules (Figure 9). BRCA1185delAG/+ breast epithelial cells exhibited a noteworthy hyperactivation of the oncogenic protein AKT, a well-known controller of protein synthesis at the level of translation initiation and ribosome biogenesis [61, 62], when compared to BRCA1+/+ parental cells. The AKT/mTOR-related activation of protein synthesis driven by BRCA1 haploinsufficiency was confirmed by the hyperphosphorylation of the proline-rich AKT substrate of 50 kDa (PRAS40) at Thr246 by AKT, which is known to act at the intersection of the AKT and mTOR-mediated signaling by relieving PRAS40 inhibition of the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) [63–65]. Interestingly, a 48 h treatment with metformin fully suppressed the activation of the AKT/mTOR-signaling network in BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells (Figure 9). Indeed, metformin-treated BRCA1185delAG/+ breast epithelial cells treatment failed to phosphorylate the pro-apoptotic protein BAD at Ser112 and the multifunctional kinase GSK-3β at Ser9, an AKT-driven signaling that is known to inhibit BAD and GSK-3β activities to promote cell survival [66, 67].

Figure 9. Metformin suppresses BRCA1 haploinsufficiency-driven activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway.

Figure shows representative chemiluminiscent array images of the PathScan Intracellular Signaling array kit revealing various phosphorylated signaling nodes in BRCA1185delAG/+ haploinsufficient and BRCA1+/+ wild-type cells cultured in the absence or presence of metformin.

DISCUSSION

In addition to oncogenic mutations, a shift towards cancer-like metabolic changes including increased aerobic utilization of glucose to produce lactate mediated by glycolysis (Warburg effect) [68] and enhanced mitochondrial utilization of glucose and glutamine to sustain anabolic processes [69–78], might pre-set an idoneous metabolic stage for later mutations to drive tumorigenesis [31–33]. Here, we present evidence that inheritance of a mutated BRCA1 allele might expedite the establishment of a metabolic state compatible and “permissive” with the elevated genomic instability found in breast epithelial cells of women carrying a non-functional copy of BRCA1.

To explore whether the one-hit event might be sufficient to shorten the time required for breast epithelial cells to become “pre-equipped” to support the metabolically-demanding process of tumor formation, we utilized a GC-EI-QTOF-MS-based metabolomic approach to examine whether metabolites involved in energy metabolism, including glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and pathways involved in metabolism of lipids, amino acids, and pentose phosphates were altered in response to “one-hit” BRCA1. Our present findings showing a dramatic accumulation of the acyl-CoA derivatives succinyl-CoA, acetyl-CoA, and malonyl-CoA accompanied by high levels of BCAAs in BRCA1185delAG/+ heterozygous cells, strongly suggest that germline mutation in a BRCA1 allele is sufficient to phenocopy multiple bona fide oncogenic pathways to stimulate glucose- and glutamine-derived carbon atom flux, promote TCA metabolism and lipogenesis, and coordinate carbon and nitrogen metabolism across amino acids to likely stimulate mTOR-driven protein synthesis [73–86].

Compounds that interfere with early stages of cancer formation are particularly appropriate for mutation carriers and evidence indicates that risk reduction strategies focused on patients harboring germ-line BRCA1 mutations are effective [87–89]. In this regard, our present results established that pharmacological ablation of BRCA1 mutation-driven hyperactivation of mitochondrial-dependent biosynthetic activity was sufficient to reduce the tumor-initiating capacity of breast epithelial BRCA1 one-hit cells in mammosphere assays. Our findings that breast epithelial BRCA1 one-hit cells produced a greater number of mammospheres than controls extend previous studies showing that breast epithelial cells from BRCA1 mutation carriers form cell colonies in non-adherent conditions with greater efficiency than control epithelial cells [54–57]. Importantly, we could establish a causal, functional relationship between the metabolic rewiring of BRCA1 one-hit cells and their increased mammosphere-forming capacity, a surrogate measure of CSCs. Thus, we concluded that metformin treatment reduced the tumor-initiating (self-renewal) capacity of breast epithelial BRCA1 one-hit cells, whereas BRCA1 wild-type cells were mostly resistant at similar doses, which is indicative of a wide therapeutic index. Remarkably, the dissimilar responses of BRCA1 one-hit cells and BRCA1 wild-type cells to metformin in terms of stemness properties directly correlated with a more drastic and specific rearrangement of the anabolic phenotype in BRCA1 one-hit cells, supporting the notion that cells with high mitochondrial metabolism are more metabolically responsive to metformin [59, 60].

Mechanistically, our results indicated that metformin targeted the tumorigenic capacity of one-hit BRCA1 cells by starving mitochondria of the necessary metabolic intermediates required for anabolic metabolism. Our TCA metabolite screen revealed that metformin treatment significantly reduced the total abundance of α-ketoglutarate, accompanied by the suppression of malonyl-CoA generation, the major building block for lipid biosynthesis. Although it might be argued that the ability of metformin to interfere with the anaplerotic entry of glutamine into the TCA cycle can explain the increased sensitivity of BRCA1 one-hit cells to its anti-tumor initiating capacity, it should be also acknowledged that metformin reduced glucose-derived acetyl-CoA entry into mitochondrial metabolism in BRCA1 one-hit cells more dramatically than in BRCA1 wild-type cells. Indeed, BRCA1 one-hit cells treated with metformin had an increased fraction of total malate within the TCA cycle while also increasing the intracellular concentration of pyruvate and lactate. The reduced usage of pyruvate by the TCA cycle accompanied by increased generation of lactate clearly indicated that metformin treatment diverted pyruvate away from mitochondrial metabolism by increasing glycolysis activity in BRCA1 one-hit cells. Therefore, inhibition of complex I-dependent mitochondrial respiration by metformin in turn inhibits the overactive TCA cycle in BRCA1 one-hit cells, which accept less glucose carbon, favoring lactic acid production. In addition, metformin treatment also impedes the glutamine contribution to anaplerotic flux into the TCA cycle, and the previously argued adaptive response to metformin involving a shift in α-ketoglutarate metabolism towards reductive carboxylation, failed to replenish the high-levels of lipogenic acetyl-CoA induced by BRCA1 haploinsufficiency. Moreover, because valine and isoleucine contain carbons that form succinyl-CoA, whereas the degradation of isoleucine and leucine forms acetyl-CoA, the ability of metformin to reduce the pool of BCAAs, which comprises almost 25% of the content of the average protein, might impede BRCA1 one-hit cells to meet their elevated demand for alanine and glutamine and protein synthesis by impairing BCCA-driven activation of mTOR and TCA fueling.

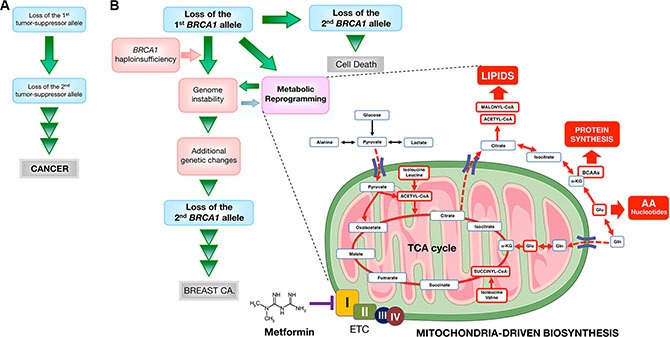

Tremendous progress has been made in the last 20 years in understanding how monoallelic BRCA1 loss leads to defects in DNA damage response, chromatin organization, gene transcription, cell division, and protein and genome stability [90–92]. Nevertheless, it remains enigmatic why a mutation in a single copy of BRCA1 leads to rapid tumor onset in a very strict tissue- and cell-type-specific manner. Our present results identify an inherited form of metabolic reprogramming and provide a conceivable metabolic basis for the rapid cell- and tissue-specific predisposition of breast cancer development associated with BRCA1 haploinsufficiency. The metabolomic signature distinguishing wild-type from BRCA1 haploinsufficient but otherwise isogenic breast epithelial cells reveals that a constitutively enhanced activation of mitochondrial-dependent biosynthesis becomes activated to sustain anabolic processes in mutant BRCA1 cells. Our findings add a new dimension to Sinclair's original proposal of geroncogenesis [31], which states that normal decline in oxidative mitochondrial metabolism during aging constitutes an early and important “hit” that drives tumorigenesis. Our findings experimentally support our recent proposal that women carrying mutations in BRCA1 might undergo a process of “accelerated geroncogenesis” in mammary epithelia [93]. The unanticipated ability of one germline BRCA1 hit to reprogram breast epithelial host metabolism towards increased anabolism should broaden our understanding of “gatekeeper” or “caretaker” tumor-suppressor genes as well as improving our knowledge of the ultimate molecular requirements for BRCA1-driven neoplastic transformation in a tissue- and cell-type-specific manner. Although heterozygous BRCA1 inactivation itself might be insufficient for complete breast carcinogenesis, the acceleration of the rate at which an “anabolic threshold” would permit the survival and expansion of genomically altered breast epithelial cells might operate as a true oncogenic event of BRCA1 haploinsufficiency-driven breast carcinogenesis (Figure 10). Further studies are warranted to determine the ultimate role of BRCA1 haploinsufficiency-driven metabolic reprogramming in the discrete evolutionary pathways occurring in BRCA1-associated breast tumors [94] and whether a similar metabolic facet should be contemplated when assessing the pathophysiology, consequences and therapeutic value of other well-known oncosuppressors.

Figure 10. Mitochondrial-dependent biosynthesis: a therapeutically targetable feature of BRCA1-driven breast carcinogenesis.

A schematic overview of the concept in the present study. (A) Original “two-hit” theory for the incidence of familial cancers proposed by Knudson [5]. (B) A modified two-hit model for BRCA1-mediated breast carcinogenesis suggested by the present study. Because BRCA1-null cells seem to require additional genetic changes for survival, BRCA1-mediated breast carcinogenesis may be considered in a distinct manner from other familial cancer syndromes that follow the two-hit theory, in which consecutive deletion of two alleles accelerates tumorigenesis. Inactivating mutations of a single BRCA1 allele leads to haploinsufficiency, which results in genomic instability in human breast epithelial cells. It has been suggested that genomic instability resulting from BRCA1 haploinsufficiency is an early but not sufficient step for BRCA1-mediated breast carcinogenesis by allowing the accumulation of additional genetic changes that enable cancer progenitor cells to evade cell death that would otherwise occur upon loss of the remaining wild-type BRCA1 allele. We propose that BRCA1 haploinsufficiency is sufficient to produce significant and chronic changes in cellular metabolism by promoting a highly anabolic phenotype compatible and “permissive” with the elevated genomic instability present in BRCA1 heterozygous cells. If BRCA1 haploinsufficiency is exclusive to specific tissue types, such as breast epithelia, metabolic reprogramming towards mitochondrial-dependent biosynthesis in normal breast epithelial cells may provide a novel explanation for the restricted tissue distribution of BRCA1 carcinogenesis and could be potentially exploited to develop prophylactic therapies for BRCA1-related cancers. The anti-diabetic mitochondrial poison metformin inhibits complex I of the electron transport chain (ETC) [97, 98], which drastically restricts the production of mitochondrial-dependent biosynthetic intermediates by reducing the anaplerotic flux of glucose, glutamine, and likely BCCAs into the TCA cycle. The ability of metformin to restrict the production of mitochondrial-dependent biosynthetic intermediates while depleting the pool of mTOR activating amino acids (e.g., leucine) might open a new avenue for “mitochondrial starvation” chemopreventive strategies in BRCA1 carriers. (AA: amino acids; Gln: glutamine; Glu: glutamate; α-KG: alpha-ketoglutarate).

Because BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells display phenotypic alterations in cell-surface marker expression [56, 95] despite their normal histological appearance [56], metabolic rewiring of the breast epithelium towards increased anabolism can be employed to provide novel metabolic biomarkers in women bearing pathogenic germline BRCA1 mutations. Moreover, the fact that BRCA1 haploinsufficiency might accelerate the geroncogenic trait that naturally occurs in the breast epithelium also provides a rationale for new preventive and therapeutic strategies based on drugs or energetic behavior tools aimed to halt the breast tissue- and epithelial cell-specific metabolic reprogramming that might occur in BRCA1 carriers. Our results indicate that metformin can limit the enhanced tumor-initiating capacity of mutant BRCA1 one-hit cells by starving them of the biosynthetic intermediates required for an efficient anabolic cell growth and survival. Together, our data support a recently proposed “substrate limitation” model of metformin action [59, 60], in which metformin restricts the production of mitochondrial-dependent biosynthetic intermediates by reducing the anaplerotic flux of glucose, glutamine, and likely BCCAs, into the TCA cycle, leading to depletion of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA required for de novo lipid biosynthesis and inhibition of mTOR-driven protein synthesis in anabolism-addicted BRCA1 haploinsufficient cells (Figure 10). These observations can be exploited to develop new metformin-based “starvation” strategies as chemopreventive and treatment options in BRCA1 carriers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

Human BRCA1 (185delAG/+) MCF10A cells with heterozygous knock-in of a 2-bp deletion of BRCA1 resulting in a premature termination codon at position 39 and MCF10A isogenic parental cells were obtained from Horizon Discovery Ltd., Cambridge, UK (Cat# HD 101–018 and HD PAR-058, respectively). Cells were routinely grown in DMEM/F-12 (Gibco, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) including 2.5 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 15 mmol/L HEPES, supplemented with 5% horse serum (HS), 10 μg/ mL insulin, 20 ng/mL hEGF, 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone and 0.1 μg/ mL cholera toxin. Cells were cultured as a monolayer at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were passaged every 3–5 days and split at 80–90% confluency, approximately 1:6–1:10.

Targeted Metabolomics

Measurements of metabolites obtained from heterozygous BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ isogenic parental cells cultured in the absence or presence of 1 μmol/L metformin (48 h) were performed by employing a previously described simple and quantitative method based on gas chromatography coupled to quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometry and an electron ionization interface (GC-EI-QTOF-MS) [37, 38].

Data analysis

Raw data were processed and compounds were detected and quantified using the Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis B.06.00 software (Agilent Technologies), respectively. MetaboAnalyst 3.0 (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/) was used to generate scores/loading plots and Heatmaps [96].

Cell viability assays

The cell viability effects of metformin were determined using the standard colorimetric MTT reduction assay. For each treatment, cell viability was evaluated as a percentage using the following equation: (OD570 of the treated sample/OD570 of the untreated sample)×100.

Mammosphere culture and mammosphere-forming efficiency

Single cell suspensions of BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ cell lines were plated in 6-well tissue culture plates previously coated with poly-2-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to prevent cell attachment, at a density of 1000 cells/mL in serum-free DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 1% L-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 2% B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 20 ng/mL EGF (Sigma) and 20 ng/ mL FGFb (Invitrogen). The medium was made semi-solid by the addition of 0.5% methylcellulose (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) to prevent cell aggregation. Mammosphere-forming efficiency (MSFE) was calculated as the number of sphere-like structures (diameter > 50 μm) formed after 7 days in the absence or presence of 1 mmol/L metformin, divided by the original number of cells seeded and expressed as a percentage (mean ± SD).

Mitochondrial oxidation of glucose and glutamine

Oxidation rates of glucose and glutamine were measured using an XFp Extracellular Flux Seahorse Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ cells (15,000/well) were treated with 1 mmol/L metformin for 24 h prior to the star of the XFp Mito Fuel Flex Test kit, which was performed in accordance with manufacturer's instructions. Each plotted value is the mean of at least 6 replicates and is normalized to Hoechst signal in each well.

PathScan sandwich immunoassay

The PathScan® Intracellular Signaling array kit (Cell Signaling Technology, #7323) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, overnight serum-starved BRCA1185delAG/+ and BRCA1+/+ cells cultured in the absence or presence of 5 mmol/L metformin for 48 h in 5% HS were washed with ice-cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 1× Cell Lysis buffer. The Array Blocking Buffer was added to each well and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the lysate was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequent to washing, the detection antibody cocktail was added to each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked streptavidin was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The slide was then covered with ECL Clarity (Bio-Rad) and images were captured.

Statistical analysis

Cell viability results are presented as the mean ± SD of at least three repeated individual experiments for each group. Two-group comparisons were performed using Student's t test for paired and unpaired values. In all cases, statistical analysis was carried out with XLSTAT (Addinsoft™) and P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 were considered significant. Results from targeted metabolomics were compared by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple pair-wise comparison tests using a significance threshold of 0.05. Other calculations including comparisons with the U of Mann-Whitney test and/or correlations were made using GraphPad Prism software 6.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Grant SAF2012-38914 to JAM), Plan Nacional de I+D+I, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Grant PI15/00285 co-founded by the European Regional Development Fund [FEDER] to JJ and Grant CD12/00672 to SFA), the Agència de Gestió d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR) (Grants 2014 SGR1227 and 2014 SGR229) and Departament d'Economia I Coneixement, Catalonia, Spain. Elisabet Cuyàs is the recipient of a “Sara Borrell” post-doctoral contract (CD15/00033, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria -FIS-, Spain). The authors would like to thank Dr. Kenneth McCreath for editorial support.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Liu Q, Cochran C, Bennett LM, Ding W, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1329–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:265–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke W, Daly M, Garber J, Botkin J, Kahn MJ, Lynch P, McTiernan A, Offit K, Perlman J, Petersen G, Thomson E, Varricchio C. Recommendations for follow-up care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to cancer. II. BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cancer Genetics Studies Consortium. JAMA. 1997;277:997–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knudson AG., Jr Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:820–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakem R, de la Pompa JL, Sirard C, Mo R, Woo M, Hakem A, Wakeham A, Potter J, Reitmair A, Billia F, Firpo E, Hui CC, Roberts J, et al. The tumor suppressor gene Brca1 is required for embryonic cellular proliferation in the mouse. Cell. 1996;85:1009–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu CY, Flesken-Nikitin A, Li S, Zeng Y, Lee WH. Inactivation of the mouse Brca1 gene leads to failure in the morphogenesis of the egg cylinder in early postimplantation development. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1835–43. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludwig T, Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE, Efstratiadis A. Targeted mutations of breast cancer susceptibility gene homologs in mice: lethal phenotypes of Brca1, Brca2, Brca1/Brca2, Brca1/p53, and Brca2/p53 nullizygous embryos. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1226–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King TA, Gemignani ML, Li W, Giri DD, Panageas KS, Bogomolniy F, Arroyo C, Olvera N, Robson ME, Offit K, Borgen PI, Boyd J. Increased progesterone receptor expression in benign epithelium of BRCA1-related breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5051–3. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cousineau I, Belmaaza A. BRCA1 haploinsufficiency, but not heterozygosity for a BRCA1-truncating mutation, deregulates homologous recombination. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:962–71. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.8.4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeng YM, Cai-Ng S, Li A, Furuta S, Chew H, Chen PL, Lee EY, Lee WH. Brca1 heterozygous mice have shortened life span and are prone to ovarian tumorigenesis with haploinsufficiency upon ionizing irradiation. Oncogene. 2007;26:6160–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burga LN, Tung NM, Troyan SL, Bostina M, Konstantinopoulos PA, Fountzilas H, Spentzos D, Miron A, Yassin YA, Lee BT, Wulf GM. Altered proliferation and differentiation properties of primary mammary epithelial cells from BRCA1 mutation carriers. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1273–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rennstam K, Ringberg A, Cunliffe HE, Olsson H, Landberg G, Hedenfalk I. Genomic alterations in histopathologically normal breast tissue from BRCA1 mutation carriers may be caused by BRCA1 haploinsufficiency. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:78–90. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konishi H, Mohseni M, Tamaki A, Garay JP, Croessmann S, Karnan S, Ota A, Wong HY, Konishi Y, Karakas B, Tahir K, Abukhdeir AM, Gustin JP, et al. Mutation of a single allele of the cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 leads to genomic instability in human breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17773–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110969108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salmena L, Narod S. BRCA1 haploinsufficiency: consequences for breast cancer. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2012;8:127–9. doi: 10.2217/whe.12.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang MK, Kwong A, Tam KF, Cheung AN, Ngan HY, Xia W, Wong AS. BRCA1 deficiency induces protective autophagy to mitigate stress and provides a mechanism for BRCA1 haploinsufficiency in tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2014;346:139–47. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savage KI, Matchett KB, Barros EM, Cooper KM, Irwin GW, Gorski JJ, Orr KS, Vohhodina J, Kavanagh JN, Madden AF, Powell A, Manti L, McDade SS, et al. BRCA1 deficiency exacerbates estrogen-induced DNA damage and genomic instability. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2773–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feilotter HE, Michel C, Uy P, Bathurst L, Davey S. BRCA1 haploinsufficiency leads to altered expression of genes involved in cellular proliferation and development. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pathania S, Bade S, Le Guillou M, Burke K, Reed R, Bowman-Colin C, Su Y, Ting DT, Polyak K, Richardson AL, Feunteun J, Garber JE, Livingston DM. BRCA1 haploinsufficiency for replication stress suppression in primary cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5496. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sedic M, Skibinski A, Brown N, Gallardo M, Mulligan P, Martinez P, Keller PJ, Glover E, Richardson AL, Cowan J, Toland AE, Ravichandran K, Riethman H, et al. Haploinsufficiency for BRCA1 leads to cell-type-specific genomic instability and premature senescence. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7505. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welcsh PL, King MC. BRCA1 and BRCA2 and the genetics of breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:705–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brekelmans CT. Risk factors and risk reduction of breast and ovarian cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:63–8. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotsopoulos J, Kim YI, Narod SA. Folate and breast cancer: what about high-risk women? Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1405–20. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0022-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB. New York Breast Cancer Study Group. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2003;302:643–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1088759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rollins G. Exercise and healthy weight in youth delay onset of breast cancer in women at highest risk. Rep Med Guidel Outcomes Res. 2003;14:7–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreau K, Dizin E, Ray H, Luquain C, Lefai E, Foufelle F, Billaud M, Lenoir GM, Venezia ND. BRCA1 affects lipid synthesis through its interaction with acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3172–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunet J, Vazquez-Martin A, Colomer R, Graña-Suarez B, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA. BRCA1 and acetyl-CoA carboxylase: the metabolic syndrome of breast cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47:157–63. doi: 10.1002/mc.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray H, Suau F, Vincent A, Dalla Venezia N. Cell cycle regulation of the BRCA1/acetyl-CoA-carboxylase complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:615–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortega FJ, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Mayas D, García-Santos E, Gómez-Serrano M, Rodriguez-Hermosa JI, Ruiz B, Ricart W, Tinahones FJ, Frühbeck G, Peral B, Fernández-Real JM. Breast cancer 1 (BrCa1) may be behind decreased lipogenesis in adipose tissue from obese subjects. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Privat M, Radosevic-Robin N, Aubel C, Cayre A, Penault-Llorca F, Marceau G, Sapin V, Bignon YJ, Morvan D. BRCA1 induces major energetic metabolism reprogramming in breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu LE, Gomes AP, Sinclair DA. Geroncogenesis: metabolic changes during aging as a driver of tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menendez JA, Alarcón T, Joven J. Gerometabolites: the pseudohypoxic aging side of cancer oncometabolites. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:699–709. doi: 10.4161/cc.28079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menendez JA, Joven J. Energy metabolism and metabolic sensors in stem cells: the metabostem crossroads of aging and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;824:117–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-07320-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang YC, Williams BR, Siegel JJ, Amon A. Identification of aneuploidy-selective antiproliferation compounds. Cell. 2011;144:499–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di LJ, Byun JS, Wong MM, Wakano C, Taylor T, Bilke S, Baek S, Hunter K, Yang H, Lee M, Zvosec C, Khramtsova G, Cheng F, et al. Genome-wide profiles of CtBP link metabolism with genome stability and epithelial reprogramming in breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1449. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaukat Z, Liu D, Choo A, Hussain R, O'Keefe L, Richards R, Saint R, Gregory SL. Chromosomal instability causes sensitivity to metabolic stress. Oncogene. 2015;34:4044–55. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cuyàs E, Fernández-Arroyo S, Corominas-Faja B, Rodríguez-Gallego E, Bosch-Barrera J, Martin-Castillo B, De Llorens R, Joven J, Menendez JA. Oncometabolic mutation IDH1 R132H confers a metformin-hypersensitive phenotype. Oncotarget. 2015;6:12279–96. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riera-Borrull M, Rodríguez-Gallego E, Hernández-Aguilera A, Luciano F, Ras R, Cuyàs E, Camps J, Segura-Carretero A, Menendez JA, Joven J, Fernández-Arroyo S. Exploring the Process of Energy Generation in Pathophysiology by Targeted Metabolomics: Performance of a Simple and Quantitative Method. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2016;27:168–77. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Del Barco S, Vazquez-Martin A, Cufí S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Bosch-Barrera J, Joven J, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA. Metformin: multi-faceted protection against cancer. Oncotarget. 2011;2:896–917. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cufí S, Corominas-Faja B, Lopez-Bonet E, Bonavia R, Pernas S, López IÁ, Dorca J, Martínez S, López NB, Fernández SD, Cuyàs E, Visa J, Rodríguez-Gallego E, et al. Dietary restriction-resistant human tumors harboring the PIK3CA-activating mutation H1047R are sensitive to metformin. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1484–95. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menendez JA, Quirantes-Piné R, Rodríguez-Gallego E, Cufí S, Corominas-Faja B, Cuyàs E, Bosch-Barrera J, Martin-Castillo B, Segura-Carretero A, Joven J. Oncobiguanides: Paracelsus' law and nonconventional routes for administering diabetobiguanides for cancer treatment. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2344–8. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anisimov VN. Metformin for cancer and aging prevention: is it a time to make the long story short? Oncotarget. 2015;6:39398–407. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vujic I, Sanlorenzo M, Posch C, Esteve-Puig R, Yen AJ, Kwong A, Tsumura A, Murphy R, Rappersberger K, Ortiz-Urda S. Metformin and trametinib have synergistic effects on cell viability and tumor growth in NRAS mutant cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:969–78. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang X, Ma N, Wang D, Li F, He R, Li D, Zhao R, Zhou Q, Wang Y, Zhang F, Wan M, Kang P, Gao X, et al. Metformin inhibits tumor growth by regulating multiple miRNAs in human cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3178–94. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Wahab Z, Mert I, Tebbe C, Chhina J, Hijaz M, Morris RT, Ali-Fehmi R, Giri S, Munkarah AR, Rattan R. Metformin prevents aggressive ovarian cancer growth driven by high-energy diet: similarity with calorie restriction. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10908–23. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loubière C, Goiran T, Laurent K, Djabari Z, Tanti JF, Bost F. Metformin-induced energy deficiency leads to the inhibition of lipogenesis in prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:15652–61. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yue W, Zheng X, Lin Y, Yang CS, Xu Q, Carpizo D, Huang H, DiPaola RS, Tan XL. Metformin combined with aspirin significantly inhibit pancreatic cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo by suppressing anti-apoptotic proteins Mcl-1 and Bcl-2. Oncotarget. 2015;6:21208–24. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ge R, Wang Z, Wu S, Zhuo Y, Otsetov AG, Cai C, Zhong W, Wu CL, Olumi AF. Metformin represses cancer cells via alternate pathways in N-cadherin expressing vs N-cadherin deficient cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:28973–87. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu Z, Zhao G, Xie G, Zhao L, Chen Y, Yu H, Zhang Z, Li C, Li Y. Metformin and temozolomide act synergistically to inhibit growth of glioma cells and glioma stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32930–43. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cazzaniga M, Bonanni B. Breast Cancer Metabolism and Mitochondrial Activity: The Possibility of Chemoprevention with Metformin. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:972193. doi: 10.1155/2015/972193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jara JA, López-Muñoz R. Metformin and cancer: Between the bioenergetic disturbances and the antifolate activity. Pharmacol Res. 2015;101:102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pizzuti L, Vici P, Di Lauro L, Sergi D, Della Giulia M, Marchetti P, Maugeri-Saccà M, Giordano A, Barba M. Metformin and breast cancer: basic knowledge in clinical context. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:441–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foretz M, Guigas B, Bertrand L, Pollak M, Viollet B. Metformin: from mechanisms of action to therapies. Cell Metab. 2014;20:953–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu S, Ginestier C, Charafe-Jauffret E, Foco H, Kleer CG, Merajver SD, Dontu G, Wicha MS. BRCA1 regulates human mammary stem/progenitor cell fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1680–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711613105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim E, Vaillant F, Wu D, Forrest NC, Pal B, Hart AH, Asselin-Labat ML, Gyorki DE, Ward T, Partanen A, Feleppa F, Huschtscha LI, Thorne HJ, kConFab, et al. Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nat Med. 2009;15:907–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bellacosa A, Godwin AK, Peri S, Devarajan K, Caretti E, Vanderveer L, Bove B, Slater C, Zhou Y, Daly M, Howard S, Campbell KS, Nicolas E, et al. Altered gene expression in morphologically normal epithelial cells from heterozygous carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:48–61. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palafox M, Ferrer I, Pellegrini P, Vila S, Hernandez-Ortega S, Urruticoechea A, Climent F, Soler MT, Muñoz P, Viñals F, Tometsko M, Branstetter D, Dougall WC, et al. RANK induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stemness in human mammary epithelial cells and promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2879–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manuel Iglesias J, Beloqui I, Garcia-Garcia F, Leis O, Vazquez-Martin A, Eguiara A, Cufi S, Pavon A, Menendez JA, Dopazo J, Martin AG. Mammosphere formation in breast carcinoma cell lines depends upon expression of E-cadherin. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andrzejewski S, Gravel SP, Pollak M, St-Pierre J. Metformin directly acts on mitochondria to alter cellular bioenergetics. Cancer Metab. 2014;2:12. doi: 10.1186/2049-3002-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Griss T, Vincent EE, Egnatchik R, Chen J, Ma EH, Faubert B, Viollet B, DeBerardinis RJ, Jones RG. Metformin Antagonizes Cancer Cell Proliferation by Suppressing Mitochondrial-Dependent Biosynthesis. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruggero D, Sonenberg N. The Akt of translational control. Oncogene. 2005;24:7426–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsieh AC, Truitt ML, Ruggero D. Oncogenic AKTivation of translation as a therapeutic target. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:329–336. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiza C, Nascimento EB, Ouwens DM. Role of PRAS40 in Akt and mTOR signaling in health and disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E1453–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00660.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang H, Zhang Q, Wen Q, Zheng Y, Lazarovici P, Jiang H, Lin J, Zheng W. Proline-rich Akt substrate of 40kDa (PRAS40): a novel downstream target of PI3k/Akt signaling pathway. Cell Signal. 2012;24:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malla R, Ashby CR, Jr, Narayanan NK, Narayanan B, Faridi JS, Tiwari AK. Proline-rich AKT substrate of 40-kDa (PRAS40) in the pathophysiology of cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg ME. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–41. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen P, Frame S. The renaissance of GSK3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:769–76. doi: 10.1038/35096075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, Thompson CB. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang C, Ko B, Hensley CT, Jiang L, Wasti AT, Kim J, Sudderth J, Calvaruso MA, Lumata L, Mitsche M, Rutter J, Merritt ME, DeBerardinis RJ. Glutamine oxidation maintains the TCA cycle and cell survival during impaired mitochondrial pyruvate transport. Mol Cell. 2014;56:414–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ahn CS, Metallo CM. Mitochondria as biosynthetic factories for cancer proliferation. Cancer Metab. 2015;3:1. doi: 10.1186/s40170-015-0128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lamb R, Ozsvari B, Lisanti CL, Tanowitz HB, Howell A, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Antibiotics that target mitochondria effectively eradicate cancer stem cells, across multiple tumor types: treating cancer like an infectious disease. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4569–84. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Luca A, Fiorillo M, Peiris-Pagès M, Ozsvari B, Smith DL, Sanchez-Alvarez R, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Cappello AR, Pezzi V, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Mitochondrial biogenesis is required for the anchorage-independent survival and propagation of stem-like cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14777–95. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lamb R, Ozsvari B, Bonuccelli G, Smith DL, Pestell RG, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Clarke RB, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Dissecting tumor metabolic heterogeneity: Telomerase and large cell size metabolically define a sub-population of stem-like, mitochondrial-rich, cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:21892–905. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farnie G, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. High mitochondrial mass identifies a sub-population of stem-like cancer cells that are chemo-resistant. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30472–86. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lamb R, Bonuccelli G, Ozsvári B, Peiris-Pagès M, Fiorillo M, Smith DL, Bevilacqua G, Mazzanti CM, McDonnell LA, Naccarato AG, Chiu M, Wynne L, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, et al. Mitochondrial mass, a new metabolic biomarker for stem-like cancer cells: Understanding WNT/FGF-driven anabolic signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30453–71. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cuyàs E, Martin-Castillo B, Corominas-Faja B, Massaguer A, Bosch-Barrera J, Menendez JA. Anti-protozoal and anti-bacterial antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis kill cancer subtypes enriched for stem cell-like properties. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:3527–32. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1044173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms through which branched-chain amino acids mediate translational control of protein synthesis. J Nutr. 2006;136:227S–31S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.227S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dodd KM, Tee AR. Leucine and mTORC1: a complex relationship. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E1329–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00525.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Durán RV, Oppliger W, Robitaille AM, Heiserich L, Skendaj R, Gottlieb E, Hall MN. Glutaminolysis activates Rag-mTORC1 signaling. Mol Cell. 2012;47:349–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O'Connell TM. The complex role of branched chain amino acids in diabetes and cancer. Metabolites. 2013;3:931–45. doi: 10.3390/metabo3040931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:133–9. doi: 10.1038/nrm3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Neishabouri SH, Hutson SM, Davoodi J. Chronic activation of mTOR complex 1 by branched chain amino acids and organ hypertrophy. Amino Acids. 2015;47:1167–82. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-1944-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Saxton RA, Shen K, Scaria SM, Cantor JR, Sabatini DM. Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science. 2016;351:43–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jewell JL, Kim YC, Russell RC, Yu FX, Park HW, Plouffe SW, Tagliabracci VS, Guan KL. Metabolism. Differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science. 2015;347:194–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1259472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kopelovich L, Shea-Herbert B. Heritable one-hit events defining cancer prevention? Cell Cycle. 2013;12:2553–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.25690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Iniesta MD, Chien J, Wicha M, Merajver SD. One-hit effects and cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:12–5. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Domchek SM, Weber BL. Clinical management of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Oncogene. 2006;25:5825–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang J, Powell SN. The role of the BRCA1 tumor suppressor in DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:531–9. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huen MS, Sy SM, Chen J. BRCA1 and its toolbox for the maintenance of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:138–48. doi: 10.1038/nrm2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roy R, Chun J, Powell SN. BRCA1 and BRCA2: different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;12:68–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Menendez JA, Folguera-Blasco N, Cuyàs E, Fernández-Arroyo S, Joven J, Alarcón T. Accelerated geroncogenesis in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome. Oncotarget. 2016;7:11959–71. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martins FC, De S, Almendro V, Gönen M, Park SY, Blum JL, Herlihy W, Ethington G, Schnitt SJ, Tung N, Garber JE, Fetten K, Michor F, et al. Evolutionary pathways in BRCA1-associated breast tumors. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:503–11. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ginestier C, Liu S, Wicha MS. Getting to the root of BRCA1-deficient breast cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:229–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xia J, Sinelnikov IV, Han B, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 3.0—making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W251–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wheaton WW, Weinberg SE, Hamanaka RB, Soberanes S, Sullivan LB, Anso E, Glasauer A, Dufour E, Mutlux GM, Budigner GS, Chandel NS. Metformin inhibits mitochondrial complex I of cancer cells to reduce tumorigenesis. Elife. 2014;3:e02242. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Luengo A, Sullivan LB, Heiden MG. Understanding the complex-I-ty of metformin action: limiting mitochondrial respiration to improve cancer therapy. BMC Biol. 2014;12:82. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0082-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]