Abstract

In vitro random mutagenesis is a powerful tool for altering properties of enzymes. We describe here a novel random mutagenesis method using rolling circle amplification, named error-prone RCA. This method consists of only one DNA amplification step followed by transformation of the host strain, without treatment with any restriction enzymes or DNA ligases, and results in a randomly mutated plasmid library with 3–4 mutations per kilobase. Specific primers or special equipment, such as a thermal-cycler, are not required. This method permits rapid preparation of randomly mutated plasmid libraries, enabling random mutagenesis to become a more commonly used technique.

INTRODUCTION

Random mutagenesis, coupled with genetic selection or high-throughput screening, is a technique for developing enzymes with novel properties, including altered substrate specificity, enantioselectivity, stability and reaction specificity (1,2). This technique has the advantage of enabling the development of new enzymatic properties without a structural understanding of the targeted enzyme, and often yields unique mutations that could not have been predicted. In addition, further improvements can be expected by repeating the mutagenesis and selection (screening) processes in a manner mimicking Darwinian evolution. This approach, called directed evolution, is a principle method for biomolecular engineering (1–3).

The most commonly used random mutagenesis method is error-prone PCR (4), which introduces random mutations during PCR by reducing the fidelity of DNA polymerase. The fidelity of DNA polymerase can be reduced by adding manganese ions or by biasing the dNTP concentration. Use of the compromised DNA polymerase causes mis-incorporation of incorrect nucleotides during the PCR reaction, yielding randomly mutated products. To convert the product to a suitable form for transformation of a host strain, at least three steps are required: digestion of the product with restriction enzymes, separation of the fragments by agarose gel electrophoresis and ligation into a vector. Although these steps do not constitute special techniques, they require almost an entire day of handling time. Further, the ligation step can sometimes be troublesome because low ligation efficiency can cause loss of the library. For these reasons, it is desirable to simplify these steps.

Another useful random mutagenesis method is the bacterial mutator strain method (5). The most popular mutator strain is Escherichia coli XL1-Red (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), which lacks three of the primary DNA repair pathways, MutS, MutD and MutT, resulting in a random mutation rate ∼5000-fold higher than in wild type. The protocol for using the mutator strain is composed of two steps: transformation of the mutator strain and recovery of the mutant from the transformant. This protocol is much simpler than error-prone PCR, and a ligation step is unnecessary. However, the mutation frequency is low under the standard conditions (0.5 mutations per kilobase) (5), and a cultivation period longer than 24 h is often required for introducing multiple mutations.

Rolling circle amplification (RCA) (6–8) is an isothermal method that amplifies circular DNA by a rolling circle mechanism (9), yielding linear DNA composed of tandem repeats of the circular DNA sequence. This method has several advantages over conventional methods for amplifying DNA, such as PCR. For example, it does not require specific primers because random hexamers can be used as a universal primer for any template (10), nor does it require a thermal-cycler because the amplification reaction proceeds at a constant temperature. In addition to the ease of amplifying circular DNA, RCA products have a unique feature in that they can be used for direct transformation of E.coli (Fujii,R., Kitaoka,M. and Hayashi,K., manuscript submitted) and yeast (11), yielding re-circularized template DNA in the transformants. Therefore, the amplified product can be used directly to transform a host strain.

We here describe the ‘simplest’ random mutagenesis method using RCA, named error-prone RCA. This method consists of only one RCA step followed by direct transformation of the host strain, and yields mutants with an adequate mutation frequency for in vitro evolution experiments (3–4 mutations per kilobase). No restriction enzymes, ligases, specific primers or special equipment such as a thermal-cycler are required. Therefore, this method is much more convenient than any other random mutagenesis methods. This method will enable random mutagenesis to become a more commonly used technique.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

E.coli strains TOP10 [F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80 lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 deoR araD139 Δ(ala-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (StrR) endA1 nupG] and DH5α [F− φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoA supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1] were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and TaKaRa (Shiga, Japan), respectively. φ29 DNA polymerase was purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA), and the restriction enzyme BamHI was purchased from TaKaRa. TempliPhi 100 DNA amplification kit was purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Ampicillin sodium salt and ceftazidime pentahydrate were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan) and Sigma (St Louis, MO), respectively. The MinElute Reaction Cleanup and QIAprep miniprep kits were purchased from QIAGEN (Hilden, Germany).

Error-prone rolling circle amplification

RCA was performed using the TempliPhi 100 DNA amplification kit, which has a sample buffer containing random hexamers that prime DNA synthesis nonspecifically; an enzyme mix containing φ29 DNA polymerase and random hexamers, and a reaction buffer containing deoxyribonucleotides. Although the exact composition of the TempliPhi kit is not known, the RCA reaction can be reproduced using φ29 DNA polymerase and exonuclease-resistant random hexamers with thiophosphate linkages for the two 3′ terminal nucleotides (10). In a total volume of 10 μl, the final concentrations were 1 U/μl of φ29 DNA polymerase and 4 pmol/μl of exonuclease-resistant random hexamers in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5), containing 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 200 ng/μl BSA, 4 mM DTT, 0.2 mM dNTP and template DNA (data not shown).

As a template for the RCA reaction, we used purified pUC19 dissolved in water or E.coli TOP10 harboring pUC19, a colony of which was picked from a Luria–Bertani (LB) medium plate using a pipette tip and suspended in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM EDTA. An aliquot (0.5 μl) of the latter was mixed with 5 μl of sample buffer, and the mixture was heated at 95°C for 3 min to denature the plasmid and to lyse the cells. The sample was cooled to room temperature immediately. The amplification reaction was started by adding a premix from the TempliPhi kit of 5 μl of reaction buffer, 0.2 μl of enzyme mix and 1 μl of MnCl2 (0–20 mM), followed by incubation at 30°C. The mixture was subsequently heated at 65°C for 10 min to inactivate the enzyme, and a 5 μl aliquot of the product was purified by using the MinElute Reaction Cleanup kit. The amount of amplified DNA was estimated by measuring its absorbance at 260 nm with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Rockland, DE).

Transformation of E.coli with RCA product

Electrocompetent E.coli (50 μl) were electroporated with a 1 μl aliquot of the RCA product using an E.coli Pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a 0.1 cm electrode cuvette at a voltage setting of 1.8 kV. The cells were incubated in 1 ml of SOC medium at 37°C for 1 h while reciprocal shaking at 160 r.p.m. and then plated onto a LB plate containing 20 ng/μl ampicillin sodium salt. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 16 h.

Characterization of plasmid in the transformant

Colonies on the plate were inoculated into LB medium containing 20 μg/ml ampicillin sodium salt, and were incubated at 37°C overnight. Plasmid DNA was isolated from the culture medium using a QIAprep miniprep kit. A 1 μl aliquot of the isolated plasmid (approx. 100 ng/μl) was digested with BamHI, and both the digested and undigested plasmids were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. All plasmids of correct size on the agarose gels were sequenced using a CEQ-2000 DNA Analysis System with a DTCS quick start kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). To measure mutation frequency in the recovered plasmid, plasmid DNA sequence was determined using an M13 (−47) primer. DNA sequences of the other regions were determined using forward primers corresponding to DNA positions 841, 1358, 1750, 2351 and 2661.

Improvement of ceftazidime resistance of TEM-1 β-lactamase using error-prone RCA

Plasmid pUC19, which contains TEM-1 β-lactamase as a marker for ampicillin, was amplified by error-prone RCA in buffer containing 1.5 mM MnCl2 in a volume of 10 μl. The product was precipitated with 70% ethanol and used to transform E.coli DH5α in 1 ml medium. To estimate the total number of transformants, a 5 μl aliquot of medium was spread on a LB plate containing 20 ng/μl ampicillin sodium salt, and the residual medium was spread on a LB plate containing 1 ng/μl ceftazidime pentahydrate, which completely inhibits the growth of E.coli containing wild-type pUC19 (12). After 16 h incubation at 37°C, colonies formed on the ceftazidime plate were inoculated into LB liquid medium containing 1 ng/μl ceftazidime. The recovered plasmids were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and the DNA sequence of the TEM-1 β-lactamase gene in each transformant was analyzed.

RESULTS

Error-prone rolling circle amplification

RCA is a laboratory method to amplify circular DNA by the rolling circle mechanism, yielding linear DNA composed of tandem repeats of the circular DNA sequence (10). The RCA product has a unique feature in that it can be used for the direct transformation of E.coli, yielding transformants containing a plasmid identical to the RCA template (Fujii,R., Kitaoka,M. and Hayashi,K., manuscript submitted). We therefore constructed a simple and rapid method for introducing random mutations into plasmid DNA. Plasmid DNA was amplified by the rolling circle mechanism in the presence of manganese ions, which has been shown to reduce the fidelity of DNA polymerases and cause random mutagenesis during RCA. E.coli was directly transformed with the RCA product, resulting in colonies containing a randomly mutated plasmid library.

Although the band mobility of the recovered plasmids on agarose gel electrophoresis was mostly identical with pUC19, there were some plasmids with lower mobility than pUC19. These plasmids with lower mobility could be multimers, which are circular DNAs having two or more repeated sequences of pUC19 (Fujii,R., Kitaoka,M. and Hayashi,K., manuscript submitted). We analyzed a total of 174 clones by agarose gel electrophoresis, resulting in 25 clones (14%) being identified as multimers. The proportion of the monomer to multimer was almost constantly independent of mutation frequency (data not shown). When the multimers were sequenced, the mutated residues were often overlapped wild-type residues. This is probably due to the multimeric structure, which contains at least two different plasmid DNA sequences. Therefore, we used only monomers in the following experiments characterizing mutations.

Mutation frequency

We found that the mutation frequency increased when the concentration of manganese increased or when the initial amount of template decreased (Table 1). A too high manganese concentration, however, was found to reduce the efficiency of amplification (2 mM MnCl2 for 25 pg pUC19). The maximum mutation frequency was 3.5 ± 1.0 mutations/kilobase.

Table 1. Effect of RCA conditions on mutation frequency.

| pUC19 (pg) | MnCl2 (mM) | Sequenced base pair | Number of mutations | Mutation frequency (mutations/kb)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0 | 5058 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 0.5 | 5976 | 1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| 25 | 1 | 6116 | 8 | 1.3 ± 0.5 |

| 25 | 1.5 | 3766 | 13 | 3.5 ± 1.0 |

| 25 | 2 | —b | —b | —b |

| 2.5 | 0.5 | 7272 | 1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| 2.5 | 1 | 4400 | 12 | 2.7 ± 0.8 |

| 250 | 1 | 4884 | 1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| 250 | 2 | 2790 | 3 | 1.1 ± 0.6 |

Plasmid pUC19 (2.5, 25 or 250 pg) was amplified by TempliPhi 100 DNA amplification kit with varying concentrations of MnCl2 (0–2 mM) for 24 h. The reaction mixture was heated at 65°C for 10 min to stop the reaction, and E.coli TOP10 was transformed with the amplified product. Plasmids were recovered from the isolated transformants, and their DNA sequence was analyzed using the M13 (−47) forward primer.

aStandard errors were calculated assuming that the values follow a Poisson distribution.

bNo transformants obtained.

When we examined the relationship between mutation frequency and amplification rate, we found that, as the amplification reaction proceeded, the mutation frequency increased (Table 2). A considerable number of mutations were introduced after 8 h of incubation, and the highest mutation frequency was obtained after 24 h of incubation.

Table 2. Correlation between reaction time and mutation frequency.

| Reaction time (h) | Sequenced base pair | Number of mutations | Mutation frequency (mutations/kb)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | —b | —b | —b |

| 4 | 6013 | 3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| 8 | 6968 | 11 | 1.6 ± 0.5 |

| 24 | 3766 | 13 | 3.5 ± 1.0 |

Plasmid pUC19 (25 pg) was amplified by TempliPhi 100 DNA amplification kit with 1.5 mM MnCl2 for 0–24 h. The reaction mixture was heated at 65°C for 10 min to stop the reaction, and E.coli TOP10 was transformed with the amplified product. Plasmids were recovered from the isolated transformants, and their DNA sequence was analyzed using the M13 (−47) forward primer.

aStandard errors were calculated assuming that the values follow a Poisson distribution.

bNo transformants obtained.

Library size

In determining the size of the mutant library produced by the error-prone RCA method (Table 3), we found that, in the presence of 1 and 1.5 mM MnCl2, 2200 and 8900 colonies, respectively, were obtained from 1 μl of the RCA product. These values were lower than that obtained under error-free conditions (38 000), indicating that increasing the concentration of MnCl2 decreased the numbers of colonies. This was due to a decrease in the yield of the RCA product and was independent of the transformation efficiencies (Table 3). This indicates that the effect of mutagenesis on the genes of the plasmid replication system may be low.

Table 3. Library size.

| MnCl2 (mM) | RCA product (ng/μl) | Number of colonies | Transformation efficiency (c.f.u./μg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 120 | 38 000 | 3 × 105 |

| 1 | 21 | 8900 | 4 × 105 |

| 1.5 | 9 | 2200 | 2 × 105 |

Plasmid pUC19 (25 pg) was amplified by TempliPhi 100 DNA amplification kit with varying concentrations of MnCl2 (0, 1 and 1.5 mM) for 24 h. The reaction mixture was heated at 65°C for 10 min to stop the reaction, and E.coli TOP10 was transformed with 1 μl of the amplified product.

Characterization of mutations

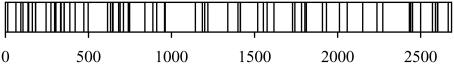

To analyze the distribution and variation of mutations caused by error-prone RCA, we isolated seven mutated plasmids from the mutant library constructed in the presence of 1.5 mM MnCl2, and each was sequenced. When we examined the distribution of mutations (Figure 1 and Table 4), we found that the mutation frequency in the region from nucleotides 800 to 2500 was slightly lower than that in other regions. Because this region encodes genes critical for the plasmid (nucleotides 867–1455 is the origin of replication, and nucleotides 1626–2486 is the ampicillin-resistance gene), some mutations in this region may have been lethal and were therefore excluded from the library. The transformation efficiency did not decrease much under error-prone conditions (Table 3), however, indicating that the influence of the lethality was trivial for the mutant library.

Figure 1.

Distribution of mutations. The seven clones produced by RCA in the presence of 1.5 mM MnCl2 from 25 pg pUC19 were sequenced. Lines indicate mutations in the pUC19 sequence. Types of mutations are described in Table 4.

Table 4. Types of mutation.

| Mutation type | Number of mutations | Percentage in substitutions |

|---|---|---|

| G to A, C to T | 43 | 66 |

| G to C, C to G | 4 | 6 |

| G to T, C to A | 7 | 11 |

| A to T, T to A | 5 | 8 |

| A to G, T to C | 5 | 8 |

| A to C, T to G | 1 | 2 |

| Insertion | 6 | |

| Deletion | 0 | |

| Total | 71 | 100 |

When we examined the diversity of mutagenesis (Table 4), we found that the direction of the mutations was biased in favor of C to T and G to A mutations (66%), and that the transition/transversion ratio was 2.7.

Improvement of ceftazidime resistance of TEM-1 β-lactamase

To verify that the error-prone RCA method can be used for evolutionary experiments, we altered the substrate specificity of TEM-1 β-lactamase using error-prone RCA. TEM-1 β-lactamase is an enzyme that hydrolyzes the β-lactam ring and is generally used as a marker for β-lactam antibiotics such as ampicillin. In contrast, this enzyme works poorly against third-generation cephalosporins, such as ceftazidime. We introduced random mutations into the TEM-1 β-lactamase gene of pUC19 using error-prone RCA in the presence of 1.5 mM MnCl2. The RCA product was used to transform E.coli DH5α, and mutants with high ceftazidime-hydrolyzing activity were selected. We found that 10 colonies grew on the LB plate containing 1 μg/ml ceftazidime, compared with 10 000 on the ampicillin plate. Of the 10 plasmids recovered from the ceftazidime plate, agarose gel electrophoresis showed that 7 had bands of the same size as pUC19, whereas the other 3 showed lower mobility than pUC19, indicating that they were probably multimeric plasmid DNA (data not shown). The seven plasmids of the same size as pUC19 were sequenced to identify mutations in the β-lactamase gene [Table 5; (13)]. All seven plasmids had mutations at R164 (to H, G or C) or at D179 (to G), all of which are known to increase the ceftazidime resistance of TEM-1 β-lactamase (14,15). Therefore, we have successfully used error-prone RCA to introduce mutations that altered the substrate specificity of β-lactamase, indicating the applicability of this method for in vitro evolution experiments.

Table 5. Mutations of the TEM-1 β-lactamase sequence in ceftazidime-resistant variants produced by error-prone RCA.

| Colony no. | Mutation | |

|---|---|---|

| DNAa | Amino acidb | |

| 1 | G485A | R164H |

| 2 | C82T, G485A, C674T | silent, R164H, A227V |

| 3 | T113G, C484G, G852A | L40W, R164G, silent |

| 4 | C484T | R164C |

| 5 | C273T, G485A, A511G, C526T | silent, R164H, I173V, R178C |

| 6 | A530G | D179G |

| 7 | A530G | D179G |

Plasmid pUC19 (25 pg) was amplified by TempliPhi 100 DNA amplification kit with 1.5 mM MnCl2 in 10 μl volume. After 24 h incubation at 30°C, the reaction was stopped by heating at 65°C for 10 min. The product was precipitated with 70% ethanol, and each precipitate was dissolved in 1 μl water and used to transform E.coli DH5α by electroporation. The transformants were spread on a LB plate containing 1 ng/μl of ceftazidime and incubated for 16 h at 37°C. The plasmids were recovered from the colonies, their size was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and plasmids of the correct size were sequenced to identify mutations in the TEM-1 β-lactamase gene.

aDNA position based on the TEM-1 β-lactamase sequence.

bAmino acid position based on the standard numbering for class A β-lactamase (13).

DISCUSSION

Random mutagenesis is a powerful tool for altering the properties of enzymes (1,2). In this study, we have developed a random mutagenesis method using the RCA technique. This method is composed of only one DNA amplification step, followed by direct transformation of the host strain. Target DNA was amplified by the RCA technique in the presence of manganese ions, which reduces the fidelity of DNA polymerase and causes the mis-incorporation of nucleic acids (4). This product is used to transform E.coli, yielding colonies that contain randomly mutated plasmids. Although we used E.coli as a host strain in this report, other hosts, including yeast (11) and probably any other host having a DNA recombination system, may also be used.

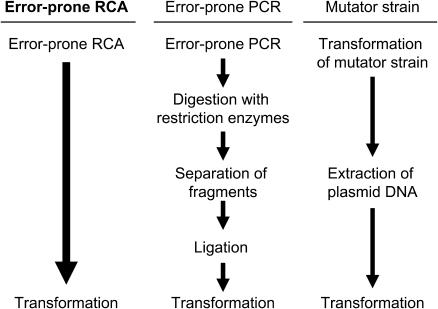

The prime advantage of error-prone RCA is its rapidity. This method consists of only one RCA step, indicating that it is much quicker than the conventional random mutagenesis methods, such as error-prone PCR or mutator strain method (Figure 2). The error-prone RCA reaction mixture can be prepared within several minutes, followed by isothermal incubation, to yield an amplified DNA suitable for direct transformation of a host strain. Specific primers for target DNA are not necessary because random hexamers can be used as the universal primer for any plasmid. Furthermore, setting of thermal-cycling conditions, as in PCR, is not necessary, because the RCA reaction proceeds under isothermal conditions. Therefore, it is no exaggeration to say that error-prone RCA is the simplest of all the random mutagenesis methods.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of error-prone RCA in comparison with the conventional random mutagenesis methods.

Using error-prone RCA, we introduced random mutations into plasmid DNA at a frequency of up to 3.5 ± 1.0 mutations per kilobase. This mutation frequency corresponds to almost one amino acid mutation per kilobase and is therefore appropriate for in vitro evolution experiments (3). In addition, the mutation frequency could be controlled by varying the concentration of manganese ions. This concentration, however, was limited to below 2 mM because excess MnCl2 decreased the RCA yield. Use of a modified φ29 DNA polymerase without 3′–5′ exonuclease activity may increase the mutation frequency (16). For example, introduction of an H61R mutation into φ29 DNA polymerase was found to result in a 16-fold increase in mis-incorporation efficiency, as well as a 6- to 23-fold increase in polymerization efficiency. These findings indicate that both mutation frequency and yield may be improved by using the H61R mutant of φ29 DNA polymerase.

While all types of substitution mutations were found in error-prone RCA variants, the mutation direction of error-prone RCA with φ29 DNA polymerase was biased in favor of C to T and G to A mutations (66%). In contrast, these mutations are less favored in error-prone PCR using Taq DNA polymerase (14%) (17). These findings indicate that error-prone RCA could give rise to a wide range of amino acid substitutions not observed in error-prone PCR.

Mutations are introduced throughout the entire plasmid by error-prone RCA, as well as in mutator strain mutagenesis (5), and mutations in regions other than the targeted gene might cause unexpected effects. The transformation efficiencies of varying concentrations of MnCl2 were almost constant, however, indicating that these mutations did not have a deleterious effect on the plasmid replication system. There are many successful reports for improving enzymatic properties by mutating the entire region of the plasmid DNA by mutator strain mutagenesis (18–20), and therefore, the influence of mutations in other regions was probably negligible.

To verify that error-prone RCA can be used to alter enzymatic properties, we used this method to increase the ceftazidime resistance of TEM-1 β-lactamase. The plasmid pUC19, which has TEM-1 β-lactamase gene, was mutated by error-prone RCA, and E.coli DH5α transformed with the RCA product was cultured on a ceftazidime plate. Of the seven mutant pUC19 plasmids with improved ceftazidime resistance, all had mutations at R164 (to H, G or C) or D179 (to G). Both of these amino acids are located at the root of the Ω-loop of the TEM-1 β-lactamase structure, which forms part of the substrate-binding domain, and mutations in these residues are known to improve ceftazidime resistance (14,15). Therefore, we have demonstrated that error-prone RCA can be used for altering enzymatic properties, indicating the applicability of this method for in vitro evolution experiments.

In conclusion, we have developed a simple method for constructing a randomly mutated plasmid library using RCA (error-prone RCA). This method was composed of one RCA step followed by direct transformation of a host strain. A target plasmid was amplified by fidelity-reduced RCA, and the host strain was transformed directly with the product to give a mutant library with up to 3.5 ± 1.0 mutations per kilobase. Use of this method will save considerable labor in the introduction of random mutants. This is the simplest protocol for the preparation of a randomly mutated plasmid library to our knowledge and will make random mutagenesis more common.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold F.H., Wintrode,P.L., Miyazaki,K. and Gershenson,A. (2001) How enzymes adapt: lessons from directed evolution. Trends Biochem. Sci., 26, 100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brakmann S. (2001) Discovery of superior enzymes by directed molecular evolution. Chembiochem., 2, 865–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reetz M.T. and Jaeger,K.E. (1999) Biocatalysis—From Discovery to Application. Springer-Verlag Berlin, Berlin, Vol. 200, pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung D.W., Chen,E. and Goeddel,D.W. (1989) A method for random mutagenesis of a defined DNA segment using a modified polymerase chain reaction. Techniques, 1, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greener A., Callahan,M. and Jerpseth,B. (1996) In Vitro Mutagenesis Protocols. Humana press, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fire A. and Xu,S.Q. (1995) Rolling replication of short DNA circles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 4641–4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu D.Y., Daubendiek,S.L., Zillman,M.A., Ryan,K. and Kool,E.T. (1996) Rolling circle DNA synthesis: small circular oligonucleotides as efficient templates for DNA polymerases. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 118, 1587–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lizardi P.M., Huang,X., Zhu,Z., Bray-Ward,P., Thomas,D.C. and Ward,D.C. (1998) Mutation detection and single-molecule counting using isothermal rolling-circle amplification. Nature Genet., 19, 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornberg A. and Baker,T. (1992) DNA Replication, 2nd edn. W. H. Freeman & Company, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean F.B., Nelson,J.R., Giesler,T.L. and Lasken,R.S. (2001) Rapid amplification of plasmid and phage DNA using Phi 29 DNA polymerase and multiply-primed rolling circle amplification. Genome Res., 11, 1095–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding X., Snyder,A.K., Shaw,R., Farmerie,W.G. and Song,W.Y. (2003) Direct retransformation of yeast with plasmid DNA isolated from single yeast colonies using rolling circle amplification. BioTechniques, 35, 774–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaytan P., Osuna,J. and Soberon,X. (2002) Novel ceftazidime-resistance β-lactamases generated by a codon-based mutagenesis method and selection. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambler R.P., Coulson,A.F.W., Frere,J.M., Ghuysen,J.M., Joris,B., Forsman,M., Levesque,R.C., Tiraby,G. and Waley,S.G. (1991) A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem. J., 276, 269–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vakulenko S.B., Taibi-Tronche,P., Toth,M., Massova,I., Lerner,S.A. and Mobashery,S. (1999) Effects on substrate profile by mutational substitutions at positions 164 and 179 of the class A TEMpUC19 β-lactamase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 23052–23060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vakulenko S.B., Toth,M., Taibi,P., Mobashery,S. and Lerner,S.A. (1995) Effects of Asp-179 mutations in TEMpUC19 β-lactamase on susceptibility to β-lactams. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 39, 1878–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Vega M., Lazaro,J.M. and Salas,M. (2000) Phage φ29 DNA polymerase residues involved in the proper stabilisation of the primer-terminus at the 3′–5′ exonuclease active site. J. Mol. Biol., 304, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shafikhani S., Siegel,R.A., Ferrari,E. and Schellenberger,V. (1997) Generation of large libraries of random mutants in Bacillus subtilis by PCR-based plasmid multimerization. BioTechniques, 23, 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camps M., Naukkarinen,J., Johnson,B.P. and Loeb,L.A. (2003) Targeted gene evolution in Escherichia coli using a highly error-prone DNA polymerase I. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 9727–9732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henke E. and Bornscheuer,U.T. (1999) Directed evolution of an esterase from Psueudomonas fluorescens. Random mutagenesis by error-prone PCR or a mutator strain and identification of mutants showing enhanced enantioselectivity by a resorufin-based fluorescence assay. Biol. Chem., 380, 1029–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bornscheuer U.T., Altenbuchner,J. and Meyer,H.H. (1998) Directed evolution of an esterase for the stereoselective resolution of a key intermediate in the synthesis of epothilones. Biotechnol. Bioeng., 58, 554–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]