Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) was identified in 1997 as a tumor suppressor gene through mapping of homozygous mutations occurring in multiple sporadic tumor types and in patients with cancer predisposition syndromes including Cowden disease (Song et al., 2012). Since that time, PTEN has emerged as one of the most frequently mutated or deleted genes in human cancers, including human skin cancers. In particular, loss of PTEN function through mutation or deletion has been observed in up to 70% of melanoma cell lines, and epigenetic silencing of PTEN has been observed in 30–40% of malignant melanomas (Mehnert and Kluger, 2012).

The PTEN protein is a lipid phosphatase that dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), a critical second messenger and activator of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Loss of PTEN function promotes cell proliferation and survival due to elevated levels of PIP3 and constitutive activation of PI3K-AKT signaling (Song et al., 2012). Studies in mice have shown that PTEN functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor, with subtle downregulation of PTEN levels promoting cancer susceptibility and tumor progression. Notably, complete loss of PTEN can also lead to cellular senescence and inhibition of tumor cell growth (Song et al., 2012). Thus, pharmacological approaches to either activate or inhibit PTEN function hold promise as novel strategies for cancer treatment. Understanding the molecular mechanisms involved in regulating PTEN protein levels and function are therefore of great importance.

PTEN activity is regulated at multiple levels, including at the level of posttranslational protein modifications involving acetylation, s-nitrosylation, oxidation, phosphorylation and ubiquitylation (Song et al., 2012). Of particular interest, phosphorylation has been proposed to play an important role in regulating the transient association of PTEN with the plasma membrane, an association that is essential for PTEN-mediated dephosphorylation of PIP3 and repression of PI3K-AKT signaling (Rahdar et al., 2009). Cycles of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation have been proposed to regulate the membrane association of PTEN by controlling a conformational switch between a closed and catalytically inactive cytosolic form, and an open and catalytically active membrane-bound form (Rahdar et al., 2009). However, molecular mechanisms regulating PTEN phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, and details of interactions between the open conformation of PTEN and the plasma membrane, remain poorly understood.

Recent work by Huang and colleagues sheds new light on the mechanisms regulating PTEN association with the plasma membrane (Huang et al., 2012). Performing studies in cultured mammalian cell lines, they discovered that PTEN is modified by the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) and that sumoylation is essential for the association of PTEN with plasma membranes. PTEN was found to be modified preferentially by SUMO-1 at two lysine residues (K254 and K266) within the central C2 domain. Inhibiting sumoylation by arginine substitutions at either of these two residues, but particularly at K266, dramatically reduced the ability of PTEN to suppress anchorage-independent cell growth in soft agar colony-forming assays and tumor growth in mice. These effects on cell growth correlated with a defect in downregulation of AKT activation, suggesting a potential defect in dephosphorylation of PIP3 at the plasma membrane. Consistent with such a defect, sumoylation-deficient mutants of PTEN exhibited reduced membrane association and elevated levels of PIP3 were detectable at the plasma membrane in cells expressing the K266R mutant. Importantly, expressing sumoylation defective PTEN mutants as linear fusions with SUMO-1 rescued defects in membrane recruitment, AKT repression and inhibition of anchorage-independent cell growth.

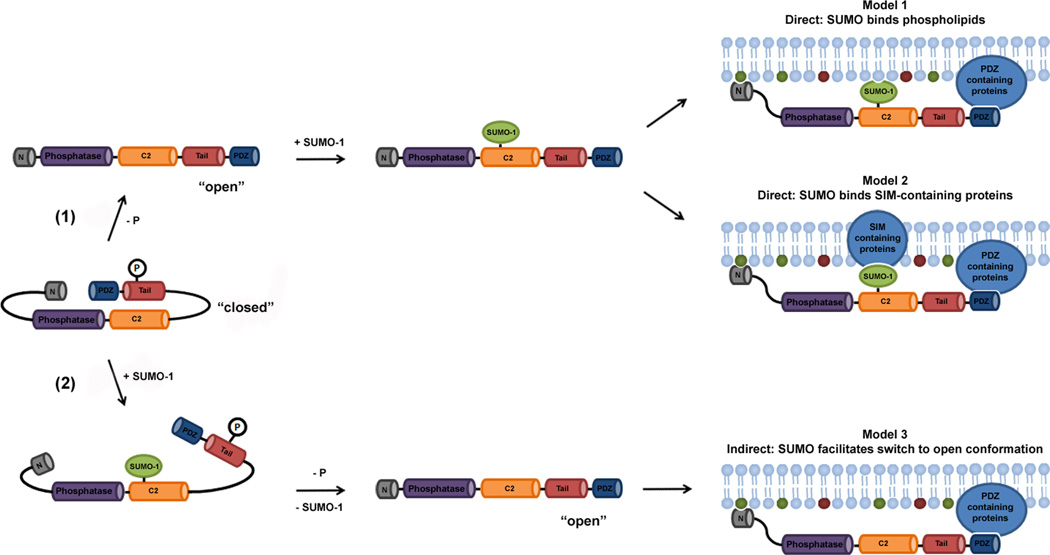

Based on these observations, and additional molecular dynamic simulations of PTEN-SUMO structures, Huang et al. proposed a model whereby sumoylation directly facilitates cooperative binding of PTEN to the plasma membrane by contributing positively charged residues for interactions with electronegative phospholipids (Figure 1, Model 1). The proposal that SUMO may directly facilitate the association of proteins with membrane phospholipids has potentially broad implications, as sumoylation has been implicated in the control of a wide range of membrane-associated processes, including vesicle transport and mitochondrial fission (Geiss-Friedlander and Melchior, 2007). Although an intriguing working model, however, other mechanisms may underlie the effect of sumoylation on the recruitment of PTEN to membranes. Sumoylation may, for example, mediate interactions between PTEN and membrane-associated proteins harboring SUMO-interacting motifs, rather than directly binding phospholipids (Figure 1, Model 2). In either case, sumoylated forms of PTEN are predicted to be enriched at the plasma membrane, a prediction that was not formally presented by Huang and colleagues.

Figure 1. Alternative models for SUMO-dependent association of PTEN with the plasma membrane.

Cytosolic PTEN is predicted to be present in a “closed” conformation unable to bind membranes. SUMO-dependent membrane association may occur through multiple direct or indirect mechanisms. (1) Dephosphorylation promotes transition to an open conformation. PTEN is modified by SUMO-1, facilitating association of PTEN with the plasma membrane. Membrane association may occur through electrostatic interactions between positively charged residues in SUMO-1 and electronegative phospholipids (Model 1), or between sumoylated PTEN and membrane-associated proteins containing SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) (Model 2). (2) PTEN is modified by SUMO-1, stabilizing a transient open conformation recognized by phosphatases. Dephosphorylation facilitates transition to the open conformation and membrane association. In the open conformation, an N-terminal PIP2-binding domain and a C-terminal PDZ-binding domain facilitate membrane association. Membrane-associated PIP2 and PIP3 are labeled green and red, respectively.

Thus, sumoylation could also promote membrane association through indirect mechanisms. It has previously been proposed that membrane association of PTEN is triggered by dephosphorylation and transition to an open conformation (Rahdar et al., 2009). Combining this model with the new findings, it is tempting to speculate that sumoylation may function upstream of membrane association by facilitating PTEN dephosphorylation and the transition from closed to open conformations (Figure 1, Model 3). Although the exact mechanism remains to be determined, evidence that sumoylation is critical for PTEN membrane association and tumor suppressor activity is very solid. Defining the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these effects is therefore an important challenge. Notably, dysregulation of sumoylation itself has been implicated in multiple human cancers, including melanomas. Of particular interest, the SUMO E2 conjugating enzyme, Ubc9, is expressed at high levels in advanced-stage melanomas where it protects cells from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis (Moschos et al., 2007). Whether effects on PTEN activity play a role in these associations with Ubc9 expression will also be important to determine. Lastly, as indicated above, pharmacological approaches to either activate or inhibit PTEN function hold promise as novel strategies for cancer treatment. The findings of Huang and colleagues identify sumoylation as an important new target for such pharmacological intervention.

Footnotes

Coverage on: Huang, J., Yan, J., Zhang, J., Zhu, S., Wang, Y., Shi, T., Zhu, C., Chen, C., Liu, X., Cheng, J., et al. (2012). SUMO1 modification of PTEN regulates tumorigenesis by controlling its association with the plasma membrane. Nat Commun 3, 911.

References

- Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:947–956. doi: 10.1038/nrm2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Yan J, Zhang J, Zhu S, Wang Y, Shi T, Zhu C, Chen C, Liu X, Cheng J, et al. SUMO1 modification of PTEN regulates tumorigenesis by controlling its association with the plasma membrane. Nat Commun. 2012;3:911. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehnert JM, Kluger HM. Driver Mutations in Melanoma: Lessons Learned From Bench-to-Bedside Studies. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0249-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschos SJ, Smith AP, Mandic M, Athanassiou C, Watson-Hurst K, Jukic DM, Edington HD, Kirkwood JM, Becker D. SAGE and antibody array analysis of melanoma-infiltrated lymph nodes: identification of Ubc9 as an important molecule in advanced-stage melanomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:4216–4225. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahdar M, Inoue T, Meyer T, Zhang J, Vazquez F, Devreotes PN. A phosphorylation-dependent intramolecular interaction regulates the membrane association and activity of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:480–485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811212106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]